AT FIRST THE explosions sounded like fireworks to Pat Neville, fifteen, a sophomore at Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, who was outside the building in the soccer field that Tuesday morning. It was April 20, 1999, the fateful day when two students dressed in black trench coats went on a murderous rampage, killing twelve students and a teacher and wounding many others before turning their guns on themselves.

Pat thought it was a senior prank until he saw something whiz through the air and land on the school’s roof. He heard a loud bang and saw a thick cloud of smoke billowing out of the building. Someone else with an assault rifle started spraying the ground, kicking up the earth outside the cafeteria. “Then a guy with a shotgun started walking toward us,” Pat remembered, “across the field. Boom. I was just like. ‘Oh, my God, is this happening?’ It didn’t even kick in.”

The feeling that the world around you is unreal or that events are not really happening is called derealization. You may think of it as a kind of jamais vu. Instead of the déjà vu feeling that new places and people are familiar, you have the opposite feeling: that people or places that you should know very well are unfamiliar. You feel estranged or detached from the environment or have a sense that the environment is foreign to you or is not real.

For most people, derealization comes on when a traumatic event turns our everyday world upside down, as it did for the young student who suddenly found that the soccer field of his placid suburban high school had metamorphosed into a killing field. Combat, the loss of a loved one, and near-death experiences are times when normal people are prone to episodes of derealization.

You can recognize derealization by these signs:

a feeling of detachment from the world

a feeling that your home, workplace, or other customary environment is unknown or unfamiliar

a sense that what is happening is not real

a sense that your friends or relatives are strange, unfamiliar, or unreal

changes in your visual perception of the environment-the sense that buildings, furniture, or other objects are changing in size or shape or that colors are becoming more or less intense

This last manifestation—disturbances in perceiving the environment—is more likely to happen in moderate or severe depersonalization than in the mild episodes experienced by normal people in an emergency. Not recognizing one’s parents, home, and friends also mainly occurs in severe derealization and not in mild, brief episodes linked to stress.

Cy, a lawyer, describes a typical brief episode of mild derealization brought on by stress. He became agitated while taking the bar exam and recalls: “It was very, very cold in the room, and I felt as if I was freezing to death. Maybe the cold got to me, I don’t know. But I looked around and saw all these people bent over their exam books, scribbling furiously. I had this sensation of things’ being very unreal, including myself. I was totally disconnected from the scene, like someone from another planet surrounded by all these strange earthlings. There was something ludicrous about it. I guess that put it in some kind of perspective, because I went back to the exam and finished it.”

As Cy’s brief episode shows, derealization commonly occurs in tandem with depersonalization—he felt unreal in that stressful situation, and so did everything around him. Although derealization rarely occurs alone, you can experience it separately You might think of derealization as a wider form of depersonalization-the feeling of detachment from yourself, your body, and your emotions extended to your immediate environment or the larger world around you.

Amnesia can coexist with derealization and frequently does in recurrent episodes. People with severe derealization may find it difficult to recognize their home or their family members and friends while remaining aware of their own identity and family history. In amnesia, forgetting familiar people is absolute, whereas in derealization there is still some intellectual connection to the people who should be familiar but aren’t. A woman knows that these people seated around the dinner table with her are her parents and siblings, for example, but she doesn’t feel related to them. They seem like strangers. She knows that this is the house of her childhood, yet it doesn’t seem like home. The landscape around her that she’s seen every day of her life seems strange and foreign to her, because she has no sense of belonging there—or having ever belonged there—at all.

Amnesia and derealization are closely linked to anxiety. Since people with high levels of anxiety have a stronger need for some form of dissociative defense, those who are more anxious experience more severe derealization. It’s not clear yet whether the anxiety precipitates the derealization or whether derealization produces the anxiety. What is known is that people with panic disorder who experience derealization are more severely anxious, obsessive, and depressed and have an earlier onset of panic attacks than those who don’t experience it. This finding could be a clue that someone who has been diagnosed with panic disorder may have an unsuspected dissociative disorder that the SCID-D can reveal.

Derealization is a prominent feature in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). People who experience flashbacks, whether they have PTSD or a dissociative disorder, relive the past as though it were occurring in the present. Superimposing a past reality onto the present makes current events seem unreal. Patients diagnosed with PTSD describe episodes of derealization on the SCID-D in the exact same terms as those used by people with dissociative disorders.

The feeling that “Mother (or whoever) is not real” reflects a disturbance in emotional memory. There’s an awareness that a familiar emotion is lacking in the normal experience of Mother. The person recognizes Mother intellectually, but the emotion is withdrawn. The person is aware that the usual emotions associated with Mother—feelings of love, closeness, comfort, and security—are missing. How does someone know who Mother is, but perceive her as not mother at the same time?

A number of theories have been advanced to explain derealization. Cognitively, it can be seen as a disruption in the normal flow of experience. Consciousness breaks down under stress, and the person becomes aware of the components of a feeling of reality instead of automatically experiencing life as real. In a crisis, for example, a person’s experience of the normal flow of time may break down into a perception that time has stopped. Similarly, the victim of childhood abuse may become aware of “behind-the-scenes” elements of consciousness and perceive a loss of a normal part of experience-the emotional bond with a loved one.

The cognitive theory of derealization implies a certain amount of voluntary control over it, similar to the way people achieve an altered state of consciousness when they meditate. Claims made by people in the SCID-D field study that they could control experiences of derealization or bring them on at will—“I can do it when I want to do it,” as one woman said-may lend some support to this theory.

Most psychoanalytic theories consider derealization to be an ego defense against overpowering anxiety. One school of thought is that when the person splits into an observing self and a participating self, the participating self is thought of as separate from the real person and imaginary. As a result, all of the outside world is also thought of as imaginary and unreal.

Another theory that fits in with the close link between dissociative symptoms and severe childhood abuse is that the abused child withdraws emotional investment from internal images of the abusers and doesn’t identify with them the same way anymore. This feeling of nonidentification carries over to other aspects of the outside world, making the familiar seem unreal.

All of these theories lead to the same conclusion: derealization is a dissociative symptom that severs a person’s consciousness from familiar perceptions of the outside world and represents a loss of familiarity with someone previously invested with that familiarity. It’s a coping strategy that helps people adjust to a traumatic event—a train wreck, a tornado, a shooting, a hostage situation—or it can occur as a childhood coping strategy for repeated abuse. However adaptive it may be when it is first experienced, if derealization persists and recurs frequently, as with all dissociative responses, it becomes maladaptive and causes difficulties with relationships, work, and inner serenity.

Normal, mild derealization—a few episodes in a lifetime that are usually not unpleasant-is common. Typically, it is brought on by stress, fatigue, hypnotic states, and alcohol or drug use.

Michael, a photographer in his thirties who uses marijuana to help him relax after a long day’s shoot, describes a typical derealization episode induced by a mind-altering drug: “I get a dreamy buzz where nothing seems to matter anymore. I feel like I’m floating out in space. Whatever someone is saying to me gets lost in the buzz. I’m in a world where my senses are the only reality. Colors almost hurt my eyes, they stand out so much. Time hardly moves at all. Everything is so, so slow. I look at the clock, and it says nine. After an hour seems to have passed, I look at the clock again, and it says five after nine. I can’t believe it. It’s as if the real world doesn’t apply to me. I’m living in a different dimension of time and space.”

Any large-scale trauma, like the Columbine High School massacre, can trigger normal episodes of derealization in the members of the community affected by it. A personal shock, if it is sudden, is unexpected, and touches a sensitive area in someone’s life, can trigger a brief episode of derealization, too, for people who are otherwise normal.

For example, Leonard, fifty-four, had been a bank manager with the same company for twenty-three years and thought he would coast along comfortably toward early retirement at sixty. The children were grown and on their own, and Leonard and his wife, an insurance claims adjuster, were building up enough savings to retire together and spend their “golden years” indulging their passion for traveling. Then, with a blow that was pitiless and final, the ax fell on their dreams.

“My boss called me into his office and told me to sit down,” Leonard recalls. “Then he let me have it. He said the company was ‘downsizing’—I hate that word!-and they were cutting my job out. They couldn’t even offer me another position with the company or transfer me to a different branch. I felt that my life had been a failure, and I was going to die. It was like a rattlesnake had bitten me on the neck. How could they do this to me after I’d been there so long? Whatever happened to loyalty?”

Leonard describes how his feelings of humiliation, betrayal, and sudden loss of identity brought on an episode of derealization that is as fresh now as the day it happened six years ago: “I looked at my boss, and suddenly I didn’t know him anymore. He didn’t look real. The room looked strange and unreal, too—almost like being out of focus. And then everything came back into focus, very much sharper. My boss had this big, abstract painting on the wall behind his desk, and the reds in it started popping out. A highly vivid red. The objects didn’t change size or shape or anything, but they were very bright. It distracted me. Other things just faded into the background, including my boss. I could hear his voice, but it was indistinct. I thought I was having a bad dream. All I wanted to do was get the hell out of there as fast as I could.”

Feelings of shame, whether they’re connected to a sense of failure and a sudden perceived loss of identity as an unemployed breadwinner or to transgressions of moral standards in sexual abuse, are a common trigger of depersonalization and derealization episodes. Problems in intimate relationships can be another trigger, particularly for women. They may feel that their identity is threatened by the actual or potential loss of the other person. Some feminist therapists believe that the way women are raised in our culture makes them prone to dissociation from their own experiences in love, because they are expected to defer to others’ standards regarding their significant relationships. Symptoms like depersonalization and derealization are signs, among others, they suggest, of the loss of control and disconnection women feel in matters of the heart.

Rachel, a forty-four-year-old marketing coordinator who had been divorced for five years, remembers a derealization episode she had when her wealthy businessman boyfriend of two years suddenly announced that he was leaving her for a model who was half her age. “He took me out to lunch to give me the bad news in a restaurant, knowing that I wouldn’t make a scene in a public place,” she recalls. “That only made me more enraged at him. It was so typical of how calculating he was. After he told me, I had this roaring sound in my ears. I could hear the other people in the room talking and laughing and clinking tableware, but the sounds were muffled. Nothing around me seemed real. It was like a scene from a movie. I thought it was a movie, and I was just imagining it. I got up from the table and walked out in a daze.”

Such transient episodes of derealization are normal if they occur on rare occasions as a response to trauma or a sudden shock to our sense of self and are not associated with amnesia or flashbacks. Rather than cause distress or dysfunction in our lives, they can help us get through the worst days of our lives in one piece.

People with moderate derealization have recurrent episodes that are not precipitated by stress and may involve disturbances in perceiving their family and home. Although many people are quite vocal about the unpleasantness of derealization, moderate episodes are not always disturbing.

Brooke, an artist, says that she finds creative inspiration in her episodes. “Spatial relationships become different,” she explains. “Colors take on special qualities. It’s almost like an intensifying and an abstraction, which give it an unreal quality.” She squints her eyes, as if visualizing an imaginary room. “I am very aware of what’s in front of me,” she says. “It’s a sofa, there, sitting in front of a fireplace, and there’s this strange mauve color, with the canary yellow curtains and all that. But there’s one way of looking at it up front, and there’s another way of drawing back and seeing it differently.”

Unlike normal episodes of derealization, a moderate episode can occur for a person’s family or home. Libby, a fifty-three-year-old documentary filmmaker whose relationship with her impossible-to-please seventy-seven-year-old mother has always been full of hurt, has episodes when her mother does not seem real to her. “I’ll be driving in the car with her, and after she has viciously attacked me, criticizing everything I’ve ever done,” Libby says, “I’ll sneak a sidelong glance at her, and she looks like a stranger to me, and I’ll hear myself thinking, ‘Who is this person? She’s not my mother. This person is not my mother.’”

Survivors of a traumatic event who are living with the emotional aftereffects of fear and anxiety may have derealization experiences that are moderate if they don’t recur frequently or interfere with their ability to function.

Terry, a police officer, was shot in the chest in the course of apprehending an armed robber. After a long recovery he retired from active duty. Although he was spared flashbacks of the shooting, Terry experienced an episode of depersonalization accompanied by derealization on occasion when he spotted someone dressed as his assailant had been.

One such episode occurred when Terry was walking down the street with his wife after seeing a movie. “We were walking to where my car was parked, and out of nowhere this guy pops up wearing an old army jacket and a gray wool knit cap pulled down low on his face,” Terry recalls. “I thought it was the guy who almost killed me. ‘He’s back to finish the job,’ I told myself. Everything around me got fuzzy, kind of blurred. I wasn’t sure whether what was happening was real or I was still in the movies. It felt like I was in a surveillance car watching it happen. The guy took something out of his pocket, and I was sure it was a gun. I felt numb, like a stone, and yet I stepped in front of my wife to protect her. But the thing in his hand was just a remote to open his car. I watched him get into his car and drive away, and then things got real again. I could hear my wife saying, ‘Are you all right?’”

Some trauma survivors, for instance, survivors of childhood abuse, have a tendency to overestimate the amount of danger in the world and may underestimate their own competency and worth. With relatively brief therapy Terry’s fears of becoming the victim of a second violent crime lessened, and he was able to control his anxiety about being attacked again without experiencing depersonalization and derealization episodes.

Derealization episodes that are rated severe cause discomfort and dysfunction and are different from mild episodes because they involve parents, home, and friends. They recur more frequently than moderate episodes and are more persistent (twenty-four hours or longer). For people with a dissociative disorder, these disturbances in perceiving the environment are usually associated with amnesia, identity alteration, and flashbacks.

Derealization without depersonalization is a feature of the dissociative disorder called DDNOS (dissociative disorder not otherwise specified), a mild variation of DID or the other dissociative disorders. My research has shown that some people with this diagnosis are eventually found to have DID.

As a posttraumatic response to ongoing childhood abuse, derealization is often experienced in connection with the person who perpetrated the abuse. If you were an abused child, perceiving the mother or father who abused you as alien to you is an attempt to make sense of the incomprehensible without losing touch with reality. It’s an emotional, but not intellectual, disconnect from your experiences of your parent as a caretaker, who was at the same time a source of crushing pain, neglect, or deprivation.

This illusory magic trick can be unsettling. “It’s very scary,” says a nineteen-year-old of the derealization episodes she experiences at home. “You feel like you’ve been dumped in the Twilight Zone. You’re faced with knowing, obviously, that this is reality, but you don’t know who these people are. Yet they’re here, and you’re in this house, and you’re living with them. You wake up and come downstairs and this lady’s serving you breakfast, and you don’t even know who she is. It’s, you know, your mother.”

In some instances derealization can take on a surreal “Alice in Wonderland” quality. As a natural reaction to trauma, this heightened reality results from a simultaneous intensified alertness and a splitting off from awareness of overwhelming emotions. People, buildings, furniture, or other objects appear to be changing in size or shape; colors seem to become more or less intense. The net effect is to turn the environment into an abstraction or make the derealized person fade away.

Rosa, a thirty-one-year-old Hispanic woman with DID and a nineteen-year history of repeated sexual abuse, says, “I have a distancing thing that happens where I get very narrow like this”—she places her palms almost touching—“and this is all I can see. And then I lose vision altogether. My eyes close and at the same time I hear a roaring sound. I thought everybody had it.”

An abuse survivor may project feelings of fear originating in childhood onto a person who serves as the abuser’s stand-in—a boyfriend or girlfriend, employer or coworker who resembles the abuser or triggers memories of the trauma. Superimposing one familiar face onto another person known to the survivor, usually a friend or loved one, has the incongruous, surreal effect of making the second person appear unfamiliar. This is a common derealization experience associated with flashbacks.

Audrey, a thirty-seven-year-old abuse survivor, was referred to me for a SCID-D by her psychiatrist who was concerned about her severe dissociative symptoms. “Sometimes when I look at my doctor,” Audrey told me during the interview, “I see the face of my father or my ex-husband, and I tell him about it right away. It’s usually because I’m afraid he’ll do the same thing to me that they have, even though there’s no reason not to trust him. He’s a very, very wonderful person, and he would never hurt me. When I was married, sometimes I’d look at my ex-husband and see my father’s face.”

A person’s employment situation may trigger derealization of the workplace in flashbacks. If the atmosphere crackles with the heat of sexual harassment or a supervisor resembles a person’s original abuser, an episode can be induced. Apart from personal interactions, many people report that episodes can be triggered by certain features in the physical environment of the workplace. Hypnotic patterns on computer screens, moving conveyor belts, flashing lights, reflective or mirrored surfaces can all stimulate the brain’s information processing system and trigger flashbacks of the original traumatic incident.

What makes derealization experienced during flashbacks so intense is that the remembered event is much more than a memory. The fear-related experience that the brain has never processed properly bursts into awareness and is so arresting that it takes over the present and makes it very unreal. As a rape victim described her flashbacks during the SCID-D: “I’d be out on a date with a boyfriend and see a totally different guy-the guy who raped me. I’d be sitting there with my boyfriend, and then, oh my God, I’d go running out of the theater.”

Faith, a woman who was sexually abused by her father, sums up the immediacy of flashbacks this way: “Flashbacks are not like snapshots that you can put in your album, and store in the back of the closet, and remember as part of your past. They’re feeling the sensations that you would have felt then now.”

Perpetrators of a crime can be as disconnected from what is happening in the present as their victims. A rapist, for example, can dissociate himself from an awareness of the violence and pain he is inflicting on an utter stranger by imagining her to be some hateful, abusive female figure in his past. Even as the woman being raped floats out of her body and imagines that the crime is happening to someone else, derealization allows the rapist to act out his rage in this violent and brutal way.

The superimposition of another reality onto the present can also involve a fantasy. Derealization probably played an important role in the murderous rampage that Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold went on in April 1999, at Columbine High School, Littleton, Colorado. In the tragic aftermath, a stunned nation wondered how these two young men, alienated as so many teenagers are yet seemingly “normal,” turned into cold-blooded sociopaths, indifferently, gleefully snuffing out the lives of any student or teacher who crossed their path. How could they be so utterly soulless and devoid of pity, ignoring the pleas of their classmates to let them live or silencing anyone who cried or moaned with another shot?

One answer turned up in the violent video games the two were obsessed with playing. Graphic effects realistic enough to blur the line between fantasy and reality allow these kill-for-thrill games to be used to break down a person’s aversion to killing. At the time of the massacre, Doom, the game favored by one of the mass murderers, was being adapted by the Marine Corps for its own training purposes. Survivors of the massacre reported that Harris and Klebold seemed to be delightedly dispatching flesh-and-blood real people as if they were animated cartoons. Brooks Brown, a classmate who’d hung out with Harris and Klebold, claimed that when the two went on their killing spree, “they were living in the moment, like they were inside a video game.” The Simon Wiesenthal Center, a tracker of Internet hate groups, discovered in its archives a copy of Harris’s website with his customized version of Doom featuring two heavily armed shooters and their helpless prey. As an Internet investigator for the center put it, at Columbine the two killers were “playing out their game in God mode.”

Harris and Klebold were pipe bombs waiting to explode in the grip of a derealization episode. Their addictive video game fantasies became their reality, and they superimposed that reality on the present when they took their revenge on the jocks and preppies who rejected and tormented them, unleashing their anger, hostility, and resentment in the bloody massacre. Feeling disconnected from their peers, they were also internally disconnected from their own humanity. It seems clear that violent video games can promote derealization in a susceptible person. For disaffected adolescents who may have undetected and untreated dissociative symptoms, spending hours and hours playing these games in isolation can be dangerous.

Despite Harris’s website and other warning signs that he and Klebold were troubled, the two received no extensive psychiatric evaluation. Ironically, after participating in a community-service program and an anger management seminar as punishment for breaking into a van and stealing electronic equipment, Harris was declared “likely to succeed in life” and Klebold “intelligent enough to make any dream a reality.” The psychiatrist who saw Harris sometime before the shooting recommended an antidepressant to alleviate his anger at the world. Klebold, a sensitive and caring person although shy and withdrawn, shocked everyone who knew him with his Jekyll and Hyde turnabout. Their fascination with neo-Nazism, death, and violent videos, along with their identity confusion and impulsivity, strongly suggests that these bright young men may have had dissociative symptoms underlying their anger and sadness. Had these symptoms been identified and treated in time, perhaps the missing links could have been filled in before their murderous fantasy overtook the real world.

Severing a person’s emotions from familiar perceptions of the outside world may be an adaptive way to cope with the fear and anxiety aroused by intense trauma or repeated childhood abuse. When derealization becomes habitual and severe, its effect on relationships, work, and peace of mind can be devastating. The oppressive feeling of living in an out-of-joint personal world can cause an agony of inner confusion and turn the real people in that world into unreal ghosts.

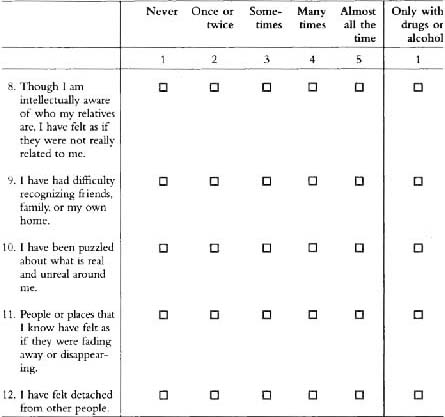

The following questionnaire will help you identify what symptoms of derealization you are experiencing and whether they are mild (normal), moderate, or severe.

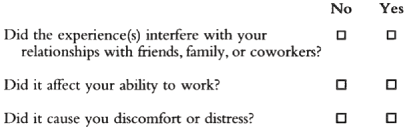

If you have had any of the above experiences, answer the following:

To Score Your Derealization Quesionnaire:

Assign a score ranging from 1 to 5 corresponding to the number on the top line above the box that you checked.

Now add up your score. Use the general guidelines below for understanding your score.

| OVERALL DEREALIZATION SCORE | |

| No Derealization: | 12 |

| Mild Derealization: | 13–20 |

| Moderate Derealization: | 21–40 |

| Severe Derealization: | 41–60 |

If your total score falls in the range of No to Mild Derealization (12–20), this is within the normal range unless you have experienced Items 9 or 10 recurrently. If you have experienced these items several times, we recommend that you be evaluated by a professional who is trained in the administration of the full SCID-D interview.

If your total score falls in the range of Moderate to Severe Derealization (21–60), we recommend that you be evaluated by a professional who is trained in the administration of the full SCID-D interview. If your derealization has interfered with your relationships with friends, family, or coworkers or has affected your ability to work or has caused you distress, it is particularly important that you obtain a professional consultation.

Should an experienced clinician find that you have a dissociative disorder, you have a treatable illness with a very good prognosis for recovery. Your illness is widely shared by others who coped with trauma by using the self-protective defense of dissociation. With proper treatment, in time, your need to disconnect from your surroundings and familiar people will diminish. Eventually, as you grow strong enough to reconnect with your hidden memories and feelings and accept them as your own, your derealization will be reduced and you will become a more integrated and psychologically healthy person.