STEVE WILLIS WAS making close to a million dollars a year as managing director at UBS, the Swiss financial conglomerate, when, still in his late thirties, he walked away from Wall Street to open two restaurants in Princeton, New Jersey, his hometown. Willis explained that although his wife, Harriette, was “incredibly supportive,” he got tired of a supposedly glamorous job that wasn’t much fun: getting up to catch the 6 A.M. train from Princeton Junction to New York and riding home on the 8 P.M.; spending 150 nights a year in hotel rooms around the world, chasing potential clients and catching a glimpse of a restaurant here and a conference room there; getting calls on a Saturday night putting him on a plane to Finland the next day, even when it was one of his kids’ birthday; for one five-year stretch missing every school play, every parent-teacher conference, and every sports match.

Willis was born with a corporate spoon in his mouth. His father was a senior vice president at Gillette, and the younger Willis felt obliged to try the executive route before concluding that more than money, he wanted happiness. When he tires of the restaurants, he’ll sell them and move on to the next thing, maybe starting up an Internet investment bank. Whatever the next step is, one thing is certain-Willis will never again be riding the 6 A.M. train every day to the Wall Street world that once defined his identity.

Steve Willis is a dazzling example of how freedom of choice has made the traditional concept of identity as a consistent and coherent entity seem somewhat outdated. Reinventing oneself from an investment banker to a restaurateur to an Internet entrepreneur hardly fits in with the American Psychiatric Association’s definition of identity as “the sense of self, providing a unity of personality over time.” It also seems to challenge the teachings of Erik Erikson, the father of the psychosocial development theory of identity: that identity is a well-organized concept of the self made up of values, beliefs, and goals to which the individual is committed.

Although most people still subscribe to the idea of a core sense of self or basic nature that guides our choices and behavior, the flexibility of self-concept demonstrated by Willis is a sign of our times. Many people today have a “working” self-concept-one in control at any given moment-that gives their lives an unprecedented complexity. In his book The Saturated Self: Dilemmas of Identity in Contemporary Life (1991), sociologist Kenneth Gergen lists some situations he encountered within a span of several months:

a neurologist, married to one woman, who spends Tuesday and Thursday nights with another woman, by whom he has a child

a male lawyer who marries a female lawyer and invites both their former lovers-both of whom are women-to the wedding

a woman who has switched careers four times in the past fifteen years, from working as a drama teacher to becoming a fund-raiser, then a stockbroker, then manager of her own antique business

“This pastiche personality is a social chameleon,” Gergen says, “constantly borrowing bits and pieces of identity from whatever sources are available, and constructing them as useful or desirable in any given situation.” This sensibility, according to Gergen, raises doubts about the need for personal coherence or consistency and makes us wonder why we need to be bound by “any traditional marker of identity-profession, gender, ethnicity, nationality.”

Although no one decries freedom of choice, many people who are influenced by this “cafeteria mentality” end up feeling confused about their options, not really knowing who they are. This cornucopia of options, they feel, places pressures on their sense of identity and makes them question the existence of a “true” self. Our culture’s emphasis on choice may be one reason why many people in the general population have a mild case of identity confusion, and those who are particularly vulnerable by reason of growing up in troubled families have a more severe degree of it.

The global economy is another reason for widespread identity confusion among normal people today. Corporate demands make it necessary for executives or professionals to uproot their families and relocate every so often or travel frequently throughout the country or abroad. As a result, many people have a shaky sense of geographical “place” or position. Add to that the uncertain nature of corporate life, with constant mergers and acquisitions and attendant layoffs and downsizings. including the category of adjustment disorder in its 1994 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSMIV) is the American Psychiatric Association’s recognition of how upsetting this particular form of contemporary stress can be to people affected by the strain of relocation or job loss.

Another fact of contemporary life, the speed and multiplicity of communications—faxes, e-mail, Instant Messenger, overnight express, and so on—can be wearing on anyone’s internal center. We also have the mass media constantly bombarding our sense of identity with dramatic portrayals of “alternative” life-styles, gossip about celebrities, and information about different cultures around the world, along with a chaotic mass of conflicting expert opinion on everything from menopause to mutual funds. TV news and newsmagazine shows, CNBC, the tabloids, movies, home videos, CDs, talk radio, Internet chat rooms and message boards, magazines, and paperbacks have all combined into a maelstrom of uncertainty about the way we’re living our lives.

And finally there is the sense of “systems overload” in people generated by the unending flow of random stimuli. People are increasingly expected to function in a “polyphasic” manner—that is, to divide their conscious attention among several different activities at the same time. An administrative aide, for example, may have to deal with people face to face, answer phones, respond to an intercom, and operate a word processor, all more or less simultaneously. Even during their free time, people who are used to polyphasic splitting of attention may “relax” by doing several things at once—driving while talking on the car phone, listening to a tape, or mentally planning a shopping list.

It may seem to be a giant leap from this kind of multilayered functioning to a dissociative disorder, but there is some evidence that modern technology is teaching the population as a whole to accept split or divided attentiveness as normal. Some theorists believe that polyphasic functioning can, over time, affect a person’s sense of identity by making it harder to distinguish central concerns from peripheral ones. When life is made up of decisions, decisions, decisions, all requiring attention at the same time, where to eat lunch on a particular day may seem as important a question as, Do I believe in God? We can get to a point where the dailiness of life matters as much as the core elements of identity: one’s fundamental beliefs, moral convictions, or close relationships.

Where does our identity come from in the first place? Choosing one theory of identity among the many that exist could itself be a cause of identity confusion. Theories of identity range across the entire map of human experience and can be grouped in four categories.

Learning theories: We acquire behavior in one of two ways: either we act in a certain way and experience the consequences ourselves, or we learn vicariously by watching how models’ behavior is reinforced.

Cognitive theories: We construct reality, conceptions of ourselves, and our moral codes by exploring our environment in a series of age-related stages and by organizing information in order to solve problems.

Psychoanalytical theories: The psyche has three divisions—the superego, a partly conscious internalization of parental moral attitudes and society’s rules, rewarding or punishing through conscience and guilt; the id, a completely unconscious grab bag of instinctual needs and drives that are a source of psychic energy; and the ego, the organized conscious mediator between the person and reality, in how the person both perceives reality and adapts to it. Conflicting mental processes, the unconscious mind, defense mechanisms, and mental representations of important others and patterns of relating formed in early childhood all shape current thought, feeling, and behavior.

Psychosocial theories: Like Erik Erikson’s, these are essentially psychoanalytic but much more society-and culture-oriented. They set out a genetically predetermined unfolding of our identities in stages, each with its own theme, time period, and developmental task to be mastered. Our progress through each stage is linked to our success, or lack of it, in all the previous stages.

Erikson’s theory is perhaps the one most relevant to identity confusion. The task of adolescence-stage five of his eight stages, beginning with puberty and ending around age eighteen or twenty—is to achieve ego identity and to avoid role confusion. To negotiate this stage successfully, we have to mold all we’ve learned about ourselves and life into a unified self-image that tells us who we are and how we fit into society. We must achieve a sense of identity in occupation, sex roles, politics, and religion.

Small children identify primarily with their parents, incorporating their beliefs, values, and behavior. As the child matures, identification extends to siblings, relatives, other significant adults, and peers. Erikson pointed out that these identifications undergo a continual process of selection and modification, making identity formation something like a kaleidoscope-an evolving configuration that is gradually established by syntheses and resyntheses of the ego.

Without adequate supports for this identity formation from adult role models, we succumb to role confusion—we’re hounded by uncertainty about our basic nature, our ideals and philosophy of life, our purpose for being here, and our place in the world. Every subsequent developmental stage will carry the curse of this impairment. As Erikson put it, “Failure is cumulative.”

As a dissociative symptom, identity confusion is a subjective feeling of uncertainty, puzzlement, or conflict about one’s sense of self. It involves difficulty understanding oneself and feelings of unhappiness resulting from internal strife. Hampered by a lack of self-knowledge, weak personal boundaries, and no coherent set of core beliefs and moral convictions, the sufferer feels an anguished “Who am I?” continually reverberating in his mind.

Many of us who thought we had that question resolved may have to revisit it and reinvent ourselves when life happens to us while we’re busy making other plans. Faced with undertaking a major change—getting married or divorced, finding a new job, moving away—we get tossed into a state of “identity shock.” Mercifully, this painful but mild identity confusion doesn’t last very long, because we still have a core identity as a foundation to support the next step.

Some people are not so blessed. Something happened along the path to an identity that derailed them. And that something is a dysfunctional relationship with family members early in life. A common thread running through all of the personality theories is that a child’s basic sense of identity depends in large measure on identification and interactions with empathetic family members who validate the child’s feelings. Abusive or inadequate parents force a child to identify with negative traits or behavior or can force a negative identity as a family scapegoat or loser on a child. A child from an abusive environment can grow up with a distorted view of the world as a dangerous, threatening, unforgiving place with a severe scarcity of options. If the child’s attempts to identify with an admired adult outside the family are criticized or thwarted by the parents, the child is a likely candidate for identity disturbances in adolescence and early adulthood.

Why are abusive parents so cruel? Some simply have poor impulse control and lash out physically when they feel angered or frustrated by the child’s needs or demands. Others momentarily identify the child with a hated or feared parent or older sibling. They may “hear” the voice of their own authoritarian parents in their child’s cries or whining and believe that the child deliberately tried to annoy them or generally “asked for it.” Some abusive parents may “read” the child’s facial expressions as a justification for abuse, misinterpreting a look as defiance or anger, and feel goaded to beat the child again. Obviously a child who is not only maltreated but verbally invalidated and accused of provoking the maltreatment is a candidate for some form of identity confusion.

The self-centeredness of parents who are blind to their children’s emotional needs is another cause of identity disturbance. So many of my patients speak of their parents in such terms as “unbelievably narcissistic,” “neglectful,” “manipulative,” “treated me like a slave,” or “acted like I was invisible” that these descriptions have become a leitmotif in their life histories.

Another dimension of parental self-centeredness is the widespread assumption that children exist to gratify their parents’ needs. This is the basic assumption underlying not only incestuous sexual abuse, but emotional abuse as well. Some parents push their children to pursue social prestige or measurable achievements-become a star athlete, win beauty contests, get into an Ivy League school—and other parents try to indoctrinate their children with certain moral standards or religious or political ideologies. If severe enough, these pressures might well create some identity confusion in children, who are uncertain about which goals or standards are their own and which have been imposed upon them by their parents.

Exploitative parents are often physically abusive, because they don’t understand the normal human developmental timetable. They beat a child for failing to live up to their unrealistic expectations of the child’s readiness for toilet training, self-feeding, and the like. As the child grows older, abusive parents are likely to continue piling on excessive and premature responsibilities—expecting a daughter to cook, clean house, and take care of younger siblings when she herself is only eight or nine. Children deprived of childhood acquire a painful sense of having no rights, only the obligation to serve the parent. Consequently they often develop impaired self-reference, an inability to know or experience their own needs or wishes apart from the reactions or demands of others.

Another form of adult exploitation of children is parental violation of the child’s psychological boundaries. Many children may be prematurely drafted into the role of confidant or amateur therapist and are forced to listen to adult problems that are beyond their level of maturity. “I was thirteen when my parents split, and my mother kept crying to me about my Dad having an affair,” a teenager recalls. “It made me feel all torn up inside. I remember writing in my diary, ‘I’m so SCARED!’”

This untimely role reversal from protectee to protector puts a child at risk for identity confusion. A teenager compelled to become a “girlfriend” to a divorced mother when she is just starting to date herself feels threatened because too much is demanded of her. Having a parent who demonstrates this kind of self-centeredness or general lack of maturity disadvantages the adolescent who has to identify with that parent before moving on to forge her own identity.

Many compromised parents have been exposed to neglect or abuse themselves, and lack appropriate role models for parenting. With psychotherapy and parenting groups they can learn healthy parenting skills and end the cycle of abuse. Men are more likely than women to inflict sexual abuse on children, and substance abuse is the most common presenting problem among reported abusers. Treatment for their substance abuse is essential not only for their own recovery but for the protection of children in their care. Many of my patients describe parents who have a “Jekyll and Hyde” personality that fluctuates with their parents’ alcohol or drug use and sobriety. Fortunately, some parents who were exposed to abuse themselves have vowed never to repeat their abuse on others. In fact, some abuse survivors, including people suffering from dissociation, are exceptionally good parents.

Some amount of identity contusion seems unavoidable in a world as complex as ours. The best insurance against it is to surround a child from infancy on with adults and siblings who exemplify a range of positive personality traits and provide a consistent and predictable source of love and support.

“When John and I got divorced, I felt as if I didn’t know who I was anymore,” says Glenda, a forty-six-year-old mother of two college-age children, talking about the identity confusion she experienced when she divorced her husband after twenty-two years of marriage. “We’d been married so long that I couldn’t grasp the concept of myself as a single woman and not part of a couple. I knew money would be a problem if I didn’t get a better job, but what was I trained to do? How could I quit without something else to go to? Should I go back to school?” She laughs ruefully and goes on, “It felt like the Titanic. You know, you’re sailing along smoothly, and all of a sudden you hit that iceberg, and water is rushing in everywhere, and you start going down. I saw it coming, but I still didn’t have a life raft. The kids tried to cheer me up with little pep talks like ‘Come on, Mom, today is the first day of the rest of your life.’ And I thought, ‘Yes, but what am I going to do with the rest of it?’ I didn’t have a clue.”

Mild identity confusion like this is common before or after a major life decision—deciding to marry or divorce, choosing a vocation, relocating geographically, going public about one’s sexual orientation, et cetera. It’s natural for these transitions to upset the internal equilibrium of someone who wants a stable sense of personal identity or has to decide among conflicting aspects of his or her identity.

Identity confusion during a period of adjustment, as in Glenda’s case, is ordinarily transient, episodic, and related to a specific stressor. As we’ve seen, this kind of mild identity confusion is not unusual in today’s age of rampant choices. It’s especially likely to occur at defining points of transition in the adult life cycle, like graduation from college, marriage, midlife, aging, retirement, and a death in the family.

Trevor, a thirty-year-old art director in his father’s advertising agency, went through a typical bout of mild identity confusion after his graduation from Parsons School of Design in New York. “I was uncertain about going into my father’s business because I didn’t know if it was what I wanted to do or what he wanted me to do,” Trevor says. He goes on with a wry grin, “Besides, at that age I thought I had this magnificent talent that the world was just waiting to discover, so I went off to Italy to study art for a year. I met serious artists who were a helluva lot more talented and passionate about their work than I was,” he confides, “and I realized that commercial art was actually more exciting for me. I came home and joined my father’s agency because, in my heart, I knew that I really loved the work and was doing it for myself.”

All of the transitions of psychosocial development involve their share of conflict and confusion. With the resolution of the crisis, the uncertainty gives way to a surer sense of comfort in one’s own skin and one’s place in the world.

When identity confusion advances beyond a transient episode related to a specific stressor and becomes a recurrent experience causing distress, it is moderate rather than mild. We can say that this kind of confusion is like a haunting melody that, for one reason or another, has become our theme song. Usually it revolves around some question about our identity that we have yet to answer.

People who are adopted often have this kind of confusion about their real identity. It’s normal for them to question their identity even if they’ve been adopted into a healthy, loving family. No matter how close they are to their adoptive parents, they’re still not related to them biologically—they might even belong to a different racial or ethnic group—and may wonder what their biological parents are like. What do they look like? Why did they give them up? Do these parents care about them at all? How are they like these parents? How are they different?

Aaron, a musician in his early thirties, was adopted in infancy by an affluent Jewish family. He loved his adoptive parents but had always felt a yearning to meet his biological mother and father. “There was a part of my life that was a mystery to me,” Aaron says. “I was basically happy, but I didn’t feel complete. There was something missing—a piece of my history that other people had for themselves and I didn’t.” With the help of an agency, Aaron tracked down his birth parents and found they were living in Ireland. “My girlfriend gave me the courage to write to my birth parents and see whether it was all right if I came to visit them,” he recalls. “I was scared to death that they’d say no, but they didn’t.”

Aaron and his girlfriend took a trip to Ireland to meet his biological parents and discovered that they were sixties “flower children” living in a commune in upstate New York when they had him. His mother explained that the pregnancy was unplanned—she wasn’t even married to his father then—and they were just too young to take on the responsibility of bringing up a child. As Catholics, they felt that abortion was out of the question and decided that giving Aaron up for adoption was the only alternative.

“Meeting them was a good experience for me,” Aaron says. “They’re two intelligent, decent people who got in a bind when they were young. I know they would’ve kept me if they’d been able to. I may never see them again-our lives are so different-but getting to know them finally gave me a feeling of being at peace with myself.”

Aaron might have had a much more severe level of identity confusion had he been adopted into a dysfunctional family rather than a healthy one. A child sent to live with abusive foster parents or taken back from adoptive parents by a surrogate mother and given a different name could grow up with severe identity confusion and a predisposition toward DID.

Confusion about one’s sexual identity or orientation frequently occurs following childhood sexual abuse or growing up in a dysfunctional family with parents who paraded their sexual activity in front of the child or aired their sexual conflicts openly. This confusion about one’s own sexual nature is more serious than the mild identity confusion related to going public about one’s sexual identity or orientation.

Valerie, a strikingly pretty thirty-seven-year-old biochemical engineer, has been struggling with confusion about her sexual orientation since late adolescence, when she first realized that she was attracted to members of her own sex. She grew up in a home where her father flaunted his mistresses in front of her mother, and her mother tore him down bitterly but stayed with him anyway. The nursemaid her mother hired for Valerie when she was little was a positive substitute identification figure. Losing her when her mother sent her away was deeply disturbing to Valerie. “My parents made it pretty hard for me to trust men or have a good opinion of them,” she says. “I grew up thinking they were all pigs.”

In her midtwenties Valerie had her first affair with a young woman her age. “I’d dated men, even enjoyed sex with some,” says Valerie, “but the passion and depth of emotion I had with this woman were unlike anything I’d ever felt before.”

Still, both Valerie and the other woman felt that they had to conform to parental and societal expectations and continued to have “public” relationships with men while secretly seeing each other. After four years of this double life, Valerie’s lover broke off their relationship, because she wanted to marry her boyfriend and start a family. “I went to her wedding in an unbelievable state of turmoil,” Valerie says. “I wanted to have a baby more than anything else in the world, but the question was, with whom? By that time I was deeply attached to another woman and was making us both miserable because I couldn’t commit to her. I wasn’t ready to give up on men entirely. My psychiatrist thought I was gay, but I didn’t want to believe it. It didn’t fit the picture in my mind of who I thought I should be. I didn’t know who I was.”

After twelve years of daily treatment with a psychiatrist, Valerie came to me for an evaluation. Her SCID-D showed that along with her confusion about her sexual orientation, she had a moderate level of depersonalization that had not been dealt with in her analysis. Her recurrent depersonalization needed to be addressed or she would stay immobilized forever. The discrepancy between her own sense of self and a mental representation based on others’ opinions had created a deep sense of shame about her actual sexual orientation. By not recognizing and treating her depersonalization, her therapy was keeping her disconnected from her true sexual identity instead of helping her discover and accept it as a part of herself independent of others’ reactions and opinions.

Valerie’s predicament speaks to the so-called deselfing of women that is widespread in our society, even in healthier families. Female children are doubly at risk for loss of self in relationships, because early in life they are taught to put the demands of others first. The pervasive cultural assumption that women exist to meet the psychological and physical wishes of others exerts a negative influence on their identity development. Inability to finish graduate or professional training, anxiety related to promotion or success, and difficulties in establishing a clear sense of identity and a “life plan” are some manifestations of this influence.

As a result of the ongoing pressure to gratify others, many women grow up with a deep sense of unmet needs, anxiety about having those needs met, and a general lack of a healthy sense of entitlement. Recent studies have shown that female adolescents in general are troubled by a sense of invalidation and invisibility—of not being listened to or responded to empathetically—and feelings of “not being able to convey or even believe in one’s own experience.” Some researchers have hypothesized that the epidemic of eating disorders among American and Western European women is directly related to women’s difficulties with selfhood and identity.

If mild or moderate identity confusion is prevalent among adults who grew up in relatively healthy families, this problem is enormously magnified for adults from abusive families, male as well as female. A clear sense of one’s identity derives in part from knowledge and acceptance of one’s gifts and interests. A boy or girl driven by fear of abusive family members and constantly on the lookout for signals of impending danger has little opportunity or energy left to define, explore, or gratify his or her own interests or desires. For this person identity confusion often rises to a higher level.

Identity confusion escalates into a persistent internal struggle tantamount to warfare in people who have suffered abuse in childhood. It involves recurrent episodes of dysfunction accompanied by strong feelings of unhappiness called dysphoria. You know your identity confusion is severe when it interferes with your interpersonal relationships or your ability to hold a job.

The magnitude of the disturbance to one’s identity wrought by emotional, physical, and/or sexual abuse in childhood is understandable. How can children who were brought up with a malevolent disregard for their needs, rights, gifts, and interests, and were constantly reviled as “bad,” “stupid,” “worthless,” or a “liar,” develop a healthy self-image? Since their whole childhood was consumed by a struggle to avoid pain at the hands of those they loved, they cannot name or define who they are, what they believe, or what they want from life in any profound or coherent fashion. Identity confusion for them goes beyond the normal transient disorientation of adolescence or divorce or the death of a partner, or an adoptee’s questioning of identity in adulthood. It widens into a deep, gaping chasm in their sense of self, driven into it by the sledgehammer of repeated abuse.

“It’s this feeling of being split, like you’re not part of your hand,” says Bob, a thirty-six-year-old patient whose employment history reads like a cryptogram with too many blanks. “When you go through adolescence and you have an identity crisis, you know you’re a whole person. You’re just trying to put your values and your sense of self in place. But this is a feeling of being split, of not being whole. You feel so many different ways, you don’t know who you are. You’re a stranger to yourself.”

Another patient, a middle-aged woman diagnosed with DID, gives this colorful description of the intensity of the daily internal struggle that puts her personal integrity at stake with every decision, even what to buy at the supermarket counter: “I feel like an amoeba with fifteen thousand different ideas about where it wants to go. And it’s literally like being pulled in every direction possible until there’s nothing left, and I feel split in half. There’s a constant battle.”

People with extreme identity confusion often experience the struggle over identity as a pitched battle or civil war waged inside themselves, even going so far as to include images of weapons and physical descriptions of the combatants. The anxiety they feel is related to fears of letting their abuse memories out and losing control over the self. “It’s like a tug of war,” says Jerry, the construction worker who earlier spoke of a huge man with jet black hair inside himself who yells “Let me out! Let me out!” during his depersonalization episodes. “Pulling, pulling the rope, pulling, you keep pulling and pulling,” Jerry says, “and he pulls you back, and you pull it forward, and he pulls you back, and you pull it forward, and you want to say, ‘Hey, man take the damn thing.’ This guy wants to come out, and he must think I’m nuts if I’m gonna let him out. If I let him out, I’m never gonna get myself back in. And that’s what scares me the most.”

Rick, a thirty-four-year-old computer programmer who grew up in an alcoholic home where he suffered physical and emotional abuse from both parents, has a battle inside him that is familiar to many men and the women they love. Before he settled down and married, Rick had a history of brawling in bars and womanizing, flitting from one short-term relationship to another as soon as there was any mention of commitment. Now, although he is deeply in love with his wife and wants to be faithful to her, an untamed part of him that still wants to carouse and have casual sex—a part modeled after his father—is at war with his responsible side. “I have this struggle about who I really am,” says Rick. “Am I just a total jerk or someone my wife wants to come home to and love and not be afraid that I’m going to leave her? Am I an intelligent, responsible adult, or do I just want to do what I want and take what I want when I want it?”

Rick goes on, obviously tortured by his identity confusion: “My wife wants to have children, but I don’t know if I’m a family guy. At heart, I feel like a guy who could have a family and really care about my wife for the rest of my life, and make a nice, easy life together. Then I feel like a guy who doesn’t care about anything or anybody, especially someone who loves me. And this guy keeps telling me that I should walk away from my wife and just have a bunch of noncommittal sexual relationships and be a big, noncaring stud.”

Sexually abused children often develop problems with their sexuality. They commonly believe that the abuse would not have taken place if their sex had been different. A male survivor of his mother’s incest, for example, may attribute the repugnant abuse to his being male and ask himself, “Why did I have to be born a disgusting boy?” Or a woman raped by her father may attribute the abuse to her vulnerability as a female and develop male alters to protect her from further victimization.

People with a dissociative disorder may have a generalized state of perplexity about their sexual orientation—like Valerie’s, but more dominant and disruptive to their lives—or may question their entire sexual identity, not knowing whether they are male or female. Those with DID who have alter personalities of the other sex may experience the internal conflict as a literal “battle of the sexes.” In a well-known instance of DID, for example, a man convicted of rape indicated that the personality who came out during the actual commission of the rapes was not only female but lesbian.

Another man I interviewed in my DID field study had been sexually abused as a child and had a blind woman inside him—typical of how powerful and metaphoric the images are. Although there was nothing wrong with his eyes, at times he couldn’t see and would walk by marking steps with the aid of a cane. He also had a part inside that felt like a ballerina. He was so confused, in fact, that he had another woman inside him with whom he had an ongoing relationship. Sometimes his involvement with the woman inside him would conflict with his attending to a real woman in his life.

Some people with severe sexual identity confusion may express a desire for a surgical sex change. “I had many periods in which I felt I needed a sex change, debated if I was a homosexual,” says Dan, a DID patient whose primary personality is male. He has pictures of himself in drag and some vague ideas of what Danielle his female alter, looks like. “I’m not sure Danielle’s happy,” he confides. “She’s not happy with my genitalia, and I’m not so sure she’s happy with my weight and bone structure. Danielle has her own agenda. She would like to see me dissolved from this person. I keep trying to tell her that if she comes out to my therapist and we work this out we’ll be one person, but she doesn’t want to be one person with Dan in charge.”

SCID-D research shows that severe identity confusion is a significant factor in DID, when one personality creates an environment that conflicts with what an alternate personality expects. “It’s like you come into work sometimes,” says Edie, a forty-year-old personnel director, “and you don’t know what you’re supposed to do that day. I’ve walked into work wondering, Who the hell am I? Not knowing: What is my job? What is my title? What am I supposed to do? And then when you start asking for help, all of a sudden you know what you’re doing there.”

Another woman known as a crackerjack executive secretary found herself in a painful situation with a new employer because an alter personality who knew nothing about typing or dictation had unexpectedly emerged in the interim before she started the new job. “It’s like my brain was damaged,” she said during the SCID-D interview. “I told the company I had ten years’ experience, but it didn’t look like I had more than a week’s experience to them. The vice president told me that I had no secretarial ability whatsoever, and yet I got straight As and was told by all my previous employers that I had A-number-one performance. This executive said, ‘I’ve been trying for ten years to get you to work for me.’ I worked for him for a month and still couldn’t perform anything, and he said, ‘I can’t believe what happened to you,’ and started yelling at me. Right now I’m learning to type all over again.”

We’re all heir to some identity confusion by reason of inevitable conflicts between our different mental processes and representations of the self. Conflicts between who we are and who we would like to be or between what we want to do and think we should are bound to confuse us at critical junctures or transitional times in our lives. Still, most of us know that although our identity is continually evolving, it has an essentially solid core with consistent preferences, goals, and ideals. Someone with dissociative identity disorder, on the other hand, is constantly wrestling with separate, often adversarial identities that are engaged in a battle for control over that person’s mind and body twenty-four hours a day.

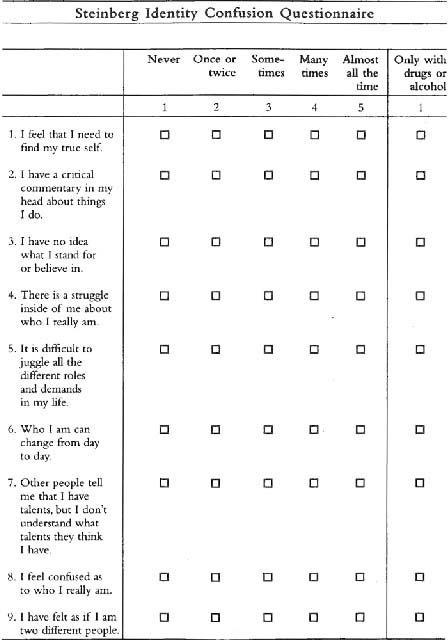

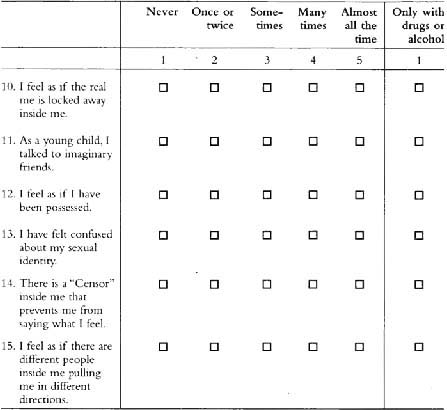

The following questionnaire will help you identify what symptoms of identity confusion you are experiencing and whether they are mild (normal), moderate, or severe.

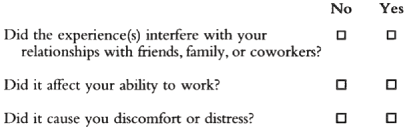

If you have had any of the above experiences, answer the following:

To Score Your Identity Confusion Questionnaire:

Assign a score of zero to the following items: Normal items: #5, 11.

For all other items, assign a score ranging from 1 to 5 corresponding to the number on the top line above the box that you checked.

Now add up your score. Use the general guidelines below for understanding your score.

OVERALL AMNESIA SCORE

| No Identity Confusion: | 13 |

| Mild Identity Confusion: | 14–19 |

| Moderate Identity Confusion: | 20–44 |

| Severe Identity Confusion: | 45–65 |

RECOMMENDATIONS

If your total score falls in the range of No to Mild Identity Confusion (13–19), this is within the normal range unless you have experienced item #9, 13, or 15 recurrently. If you have experienced these items several times, we recommend that you be evaluated by a professional who is trained in the administration of the full SCID-D interview.

If your total score falls in the range of Moderate to Severe Identity Confusion (20–65), we recommend that you be evaluated by a professional who is trained in the administration of the full SCID-D interview. If your identity confusion has interfered with your relationships with friends, family, or coworkers or has affected your ability to work or has caused you distress, it is particularly important that you obtain a professional consultation.

Should an experienced clinician find that you have a dissociative disorder, you have a treatable illness with a very good prognosis for recovery. Your illness is widely shared by others who coped with trauma by using the self-protective defense of dissociation. With proper treatment, in time your confusion about who you are will diminish. Eventually, as you grow strong enough to reconnect with your hidden memories and feelings and accept them as your own, your identity confusion will be reduced and you will become a more integrated and psychologically healthy person.