“I HAVE το wear so many hats around here that I feel like a quick-change artist,” says Angelo, the overworked administrator of a government legal services agency. “When I’m with a client who wants me to take on a giant corporation, I have to play the tough guy. When I’m with a client who’s going crazy in a custody battle, I have to play the shrink. When one of the other lawyers in the office comes to me with a question about a case, I’m the jefe, the supervisor. I guess I like being a supervisor better than dealing with clients, because there aren’t any head fakes involved. I can wear just one hat all the time.”

What Angelo is talking about is identity alteration in its mildest form—the donning of “different hats” or change of roles that most of us experience in the course of our work or personal lives. This kind of role playing and role switching is widespread in daily life—acting with buttoned-down propriety at work and turning into a party animal on the weekends; behaving like “mommy” or “daddy” with our young children and a peer with our friends. In these situations, we’re usually conscious of the role performance or switching and feel that it’s under our control.

SCID-D research has found that identity alteration, as with all the dissociative symptoms, occurs along a spectrum of intensity: mild levels of severity in the general population; mild to moderate levels in people with nondissociative psychiatric disorders, but also with dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (DDNOS); severe levels of identity alteration in people with such dissociative disorders as DID.

A person with moderate levels of identity alteration may act as if he or she is like two (or more) different people, but it’s not clear whether these identity alterations assume complete control of the person’s behavior or represent separate personalities. A normally shy person who gets drunk at a party, for example, may turn into a lampshade-on-the-head scene maker or an X-rated sexual provocateur, but may merely be disinhibited from constraints on his or her usual self rather than under the control of a distinct identity fragment.

Severe identity alteration, the sine qua non of DID, involves a person’s shifting between distinct personality states that take control of his or her behavior and thought. These alter personalities are more clearly defined and distinctive than the personality fragments that characterize moderate levels of identity alteration. Each alter has its own name, memories, traits, and behavior patterns.

Identity alteration differs from identity confusion in that identity confusion represents the internal dimension of identity disturbance, whereas identity alteration represents the external diimension. A person with identity confusion, in other words, has thoughts and feelings of uncertainty and conflict related to his or her identity; a person with identity alteration manifests the uncertainty and conflict behaviorally.

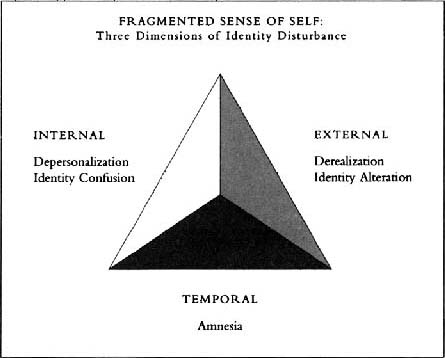

It might be helpful to think of identity disturbance as a kind of psychiatric Bermuda Triangle with three dimensions—temporal, internal, and external (see accompanying diagram). The five core symptoms of dissociation make up the triangle’s three planes. Amnesia, the fundamental symptom in relation to the other four, is the temporal or time line plane of disturbance at the base of the triangle. Depersonalization and identity confusion are the internal plane of subjective thoughts and feelings about oneself. Derealization and identity alteration are the external plane of relating to the environment and other people.

Amnesia can be thought of as a rupture in the temporal continuity of a person’s identity. When someone can’t remember large blocks of time, that person’s sense of identity as a continuous life story with a narrative “shape” and a coherent sequence of events over time is compromised or lost. Depersonalization and identity confusion can be thought of as a person’s loss of a coherent internal self-image with a reliable structure. And finally, derealization and identity alteration can be defined as disturbances in perceiving where one stands in the world and acting out of the loss of grip on one’s stance in physical space. Fugue episodes of “sleepwalking” or traveling to another city or country in a state of dissociation, a frequent occurrence in DID and dissociative fugue, can be seen from this angle as a spatial expression of identity disturbance. Acting like a different person with others is another expression of this disturbance in the outside world.

The difference between this figurative Bermuda Triangle and the real one is that whatever disappears into the real Bermuda Triangle is never found again, whereas in identity disturbance the “lost” parts trapped in the figurative triangle can be reclaimed. Accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment can help someone reconnect with the dissociated parts of the self and reintegrate them into a cohesive sense of identity.

As diverse as they are, the many theories of identity formation that have been advanced over the centuries have one aspect in common: none of the theorists understood human identity to be a monolithic given. All of the schools of thought were based on the assumption that identity is a construct, built up by the individual from a set of different elements, experiences, capacities, or components. In addition to different layers of consciousness, we have basic instinctual drives and a conscience; faculties of reason, emotion, will, and so on; capacities for analysis and logical thought in the left brain and intuitive, artistic, and musical capacities in the right; a predisposition toward introversion or extroversion; characteristics like agreeableness, sociability, conscientiousness, and ambition; and so on.

Fragmented Sense of Self: Three Dimensions of Identity Disturbance

In the normal course of development, despite the glorious variety and complexity of all our parts, we are usually able to integrate our ongoing interactions and dialogue with our social surroundings into a coherent sense of self. We accomplish this principally by identifying with influential others and choosing qualities of theirs to incorporate into ourselves.

To some extent the early stages of DID in childhood can be understood as a disturbance of the normal process of identification. Many DID patients have alters who are essentially modeled after their original abusers. There is some evidence that an alter might also have started out as an imaginary playmate modeled after a real-life or fictional identification figure. Some researchers believe that being forced to identify with parents who have mutually contradictory personality traits-loving one minute, violent the next-coupled with the loss of a more positive identification figure, such as a grandparent or a caretaker, disturbs the normal identification pattern. Since it’s impossible for the child who is developing DID to integrate incongruous loving versus abusive identifications with a parent, these identifications remain dissociated and form the nuclei of alter personalities.

Furthermore, once dissociative symptoms develop, the child may begin to behave in a way that either provokes additional maltreatment by the original abusers or makes it difficult to attract supportive attention from adults outside the immediate family who are better role models. Constantly accused of being “bad,” an “airhead,” or a “liar,” the child continues to resort to dissociation as an accommodation to ongoing abuse, and the cycle continues. By the time an adult survivor manifests the symptoms of full-fledged DID, the level of identity confusion and identity alteration is usually far more severe than the milder forms of role switching common to most of us.

Belinda was tempted to bawl out the obnoxious passenger in seat 15C as she would have if one of her young nephews dared to come into her house and behave that way. The passenger was acting worse than a belligerent six-year-old. He’d obviously had too many martinis and was loudly shouting obscenities to someone across the aisle and had even thrown a roll from his dinner plate at him, narrowly missing the head of the woman in the next seat. As much as Belinda wanted to vent her anger, she knew she couldn’t. Her job as a flight attendant demanded a courteous, pleasant demeanor and respectful attitudes toward everyone on board, no matter how a person tried her nerves. So, taking a deep breath, Belinda walked down the aisle to 15C and said in a firm but polite voice, “Sir, I’m going to have to ask you to show more consideration for the other passengers on this flight. Please lower your voice, watch your language, and do not throw anything else at anyone on the plane.”

Belinda’s awareness that her job required her to be more patient with obstreperous passengers than she would be with misbehaving visitors to her household led her to assume an “official” personality different from her nonwork personality. This deliberate kind of role switching in circumstances in which the person feels it is warranted typifies identity alteration at its mildest level. All of us, to some extent, have a public persona or face we present in formal situations and a private persona when we feel free to let our hair down. This conscious form of identity alteration that we perceive to be under our control is generally not associated with dysfunction or dysphoria and is not considered to be a problem or a sign of a disorder.

Actors engage in mild identity alteration every time they play a role. Other kinds of performers do, too. Stan, a “shock jock” radio talk show host in Miami, says, “Being bombastic and opinionated is part of the act. I couldn’t get ratings without being outrageous. The listeners eat it up when I’m rude to certain callers and hang up on them. That’s not something I would do in real life. I don’t have it in me to be mean to people except when I’m on the air and putting on a show. Ask my wife and kids. They think I’m a pussycat.”

There are times when a person might have to act like a professional with someone close. A doctor on duty in the ER, for example, might be called upon to treat a friend who’s been injured in an accident. The doctor thinks, “This is my friend, but I have to deal with him like any other patient.” The role switch is an intentional decision. Similarly, married or romantically involved couples who work together usually assume personalities with each other in the office that are quite different from their personalities as intimate partners at home.

Conscious role switching has become such a part of our lives today that not being able to switch when the situation demands it is a problem for some people. “I come home from making executive decisions and giving orders all day at the office,” says Colette, a high-level manager at a pharmaceutical firm, “and it takes me a while to shift gears sometimes. My husband complains that I’m hyper and tells me to chill out, and my five-year-old daughter says, ‘Mommy, why are you talking to me in your boss voice?’ The trouble is, in my head I’m still at the office. I’m trying to make the trains run on time instead of just being a wife and mother.”

The dissociation that our society demands of us in ordinary role switching is not always easy to bring off in the workplace. Most people have been socialized to keep personal matters separate from their work lives. Someone whose job performance begins to suffer because of preoccupation with family difficulties may be criticized or reprimanded by a supervisor. Even if that doesn’t happen, the person may be concerned about an inability to compartmentalize the strong feelings that are intruding during work hours. Don, a mergers and acquisitions specialist who is going through acrimonious divorce proceedings, says: “My wife’s lawyer is putting me through hell—she wants the moon—but I can’t let my marital troubles interfere with my work. Unfortunately it’s not that easy to separate the two. How can you put on a happy face when you’re all torn up inside? But if you show you’re weak at the office, you pay for it. You can get pushed around and find that the best deals are passing you by.”

Whether or not we switch roles easily between our “work” personality and our “private” personality, most of us experience this mild form of identity alteration in the course of ordinary life. These transitions are usually made consciously and perceived as being under our control and are not ordinarily associated with amnesia or dysfunction.

Moderate identity alteration differs from its milder counterpart in that the alterations are not always under the persons control. Although these altered states may be perceived by the person as uncontrollable, they are not always manifestations of complete personalities as they are in someone who experiences severe identity alteration.

This middle level between mild and severe identity alteration may be characteristic of such nondissociative psychiatric disorders as manic-depression, or bipolar disorder, as it is now called. A person who has bipolar disorder often feels like “two different people,” depending upon whether his mood is manic or depressed, and may attribute the moderate identity alteration that characterizes the illness to an uncontrollable temper.

“Sometimes I would just snap out for no reason at all,” says Nick, a fifty-two-year-old automobile mechanic, of his behavior before he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and stabilized on medication. “I lashed out at everybody when I was in a bad mood. It didn’t matter who it was, I let em have it. It’s just something that came over me. I felt like I was driving a car with no brakes, going ninety miles an hour, and couldn’t stop. I never hit my wife or kids, but when I got mad I’d smash my fist through a wall. A lot of the time, though, I wasn’t like that at all. I was quiet and pretty much kept to myself. There was no in-between with me. I was one way or the other, like two different people. My wife always said she didn’t know who to expect when I came in the door.”

Had Nick manifested the presence of the other four dissociative symptoms to a significant degree, his diagnosis would not have been bipolar disorder but DID. In that case his mood changes would not have been attributed to a bad temper; they would have been caused by the shift from one alternate personality to another.

People who’ve been diagnosed with borderline personality disorder also tend to fluctuate rapidly between radically different types of behavior and mood. If these moderate identity alterations coalesce around distinct personalities with different names, memories, preferences, ages, or amnesia for past events, the temper outbursts and other changes in mood and behavior could be the result of DID.

My SCID-D research has shown that people diagnosed with a dissociative disorder not otherwise specified (DDNOS), which might be considered a milder form or an early stage of DID, experience moderate levels of identity alteration. They may act like two or more different people, but it’s not clear whether these alterations assume control of their behavior or represent complete personalities. When people with DDNOS experience a conflict between the person they usually are and some fragment of their identity, their personality fragments are less clearly defined and distinctive than those that characterize severe identity alteration in DID.

Vince, the former professional wrestler who was sent to me for a SCID-D after he developed severe amnesia and could remember nothing of his past except his three children and the family dog, first displayed only moderate identity alteration. In his dissociative states he saw shadowy “dark people” of all sizes and shapes—“tall, short, fat, skinny”—who held him down, strangled him, stuck needles in him, and threatened to take over his soul or kill him if he didn’t do what they wanted. As menacing and scary as these “people” were, they were too vague and amorphous to be considered separate personalities. Since Vince’s dissociative symptoms didn’t meet the criteria for DID, he was originally diagnosed with DDNOS. It was not until Vince remembered being sexually abused by priests in Catholic school in his childhood that the “dark people” came into focus more clearly as distinct personalities modeled after his abusers, and the diagnosis of DID was made.

Substance abusers are another group of people who experience moderate levels of identity alteration when they are under the influence of drugs or alcohol. Says Carla, the wife of an alcoholic police officer who underwent a treatment program for his addiction and is now sober, “My husband was another person when he got drunk. He was a good-natured guy when he was sober, but when he was drunk—look out! He turned into a maniac. He screamed and cursed and threw things. The things he said, I couldn’t believe they were coming out of his mouth. He didn’t even look like the same person. After he sobered up, he’d say, ‘It was the booze talking.’ He’d be himself and everything would be fine—until the next time. It was like, what is this? I’m married to two different people.”

These dramatic transformations are typical of many substance abusers who seem to be “another person” under the influence of drugs or alcohol. The danger here is that alcohol or drugs can mask a person’s underlying dissociative disorder and cause the symptom of identity alteration to be written off. This is not unlike what occurs when a person with a shoulder injury thinks that the pain radiating down his arm is a result of his injury, although in fact it may be the precursor of a heart attack.

The same could be said of automobile drivers who are normally mild-mannered but assume a hostile and aggressive personality behind the wheel. Stressful traffic conditions coupled with the freedom of anonymity inside a car can remove normal constraints on a person’s behavior, as “road rage” incidents show. Unless the person has other severe dissociative symptoms, the “driver” personality is probably not a separate, distinct personality fragment characteristic of the severe identity alteration in DID.

Unlike the person who is in control of a shift in roles, someone who has severe identity alteration experiences loss of control over his or her consciousness and behavior to a separate and distinctive alter personality The person with severe identity alteration feels as if there are one or more different people inside who are capable of influencing or controlling his or her behavior. Each alter has its own name, memories, style of dress, speech pattern, handwriting, even physical ailments like headaches and allergies. When the alter emerges, the person may experience age regression as well as changes in voice, manner of speaking, dress style, body posture, and movements. Having an alter of a different sex may prompt the person to consider implementing a sex-change operation.

This shifting between distinct personality states that control a person’s thoughts, memory, behavior, and emotion is the hallmark of DID. The “Ping-Pong” state of mind that we all experience when we’re weighing pros and cons is a minor skirmish compared with the full-scale mental warfare experienced by someone with severe identity alteration. Having different alters arguing with each other or trying to seize control over the “host” personality makes a person’s head feel like a “milkshake,” as one of my DID patients said. This, I think, is an apt description of a fragmented sense of self bubbling and churning with contradiction and divisiveness.

Signs of severe identity alteration include

referring to yourself by different names

referring to yourself as “we”

acting like a completely different person at times

being told by others that you seem like a different person

feeling possessed by demons or spirits

finding items in your possession that you don’t remember having purchased

having marked differences in your memory recall

experiencing a sudden loss of skills you previously had

finding documents written by you in a different handwriting

displaying knowledge of a subject or language you don’t recall having studied

acting as if you are still a child

Severe identity alteration is accompanied by marked distress or dys-functionality and may cause job loss, troubled personal relationships, alcohol or drug abuse, or involvement with the criminal justice system.

Amazingly, many people with DID are able to hold down jobs and maintain stable relationships by walking a tightrope of wily compensatory tactics. Eventually some unexpected trigger trips them up, and they fall, dragging their tenuously held-together public persona and their internal house of cards down with them. That is why it is imperative for someone to recognize the signs of severe identity alteration and seek treatment for them as soon as possible with a therapist who can administer the full SCID-D and make a diagnosis.

Once it’s been determined that a person does indeed have a dissociative disorder, the right therapy can bring about cooperation among the different personalities, so that they will not tear that person apart. Erika, a forty-two-year-old DID patient who has many alternate personalities, is managing to maintain a successful career in human resources with a large corporation by having a personality she calls the “Professional” take charge of her work life. Her primary personality held an internal conference and explained to her alters why it was important that they not come out while she and the Professional were on the job: “I sensed that all the personalities were there, so I had a talk with each one of them,” says Erika. “We have a chart because there are so many. I explained to each one how I could lose my job if anyone except the Professional came to work. I said, You’ve got to promise to stay home tomorrow, and if you stay home and you’re good, I will tell you what happened at work’—kind of how you talk to a child. And it worked. Since then, they’ve never come to to work.”

Before she entered treatment, Erika felt that a “humongous” battle was going on inside her, a clashing of personalities that made her daily life a struggle for survival—both psychologically and on the job. Sometimes the energy consumed by this battle rendered her unable to talk. Erika, a tall, lovely-looking blond-haired woman who is dignified and composed though she had been sexually abused by her father throughout her childhood, recalls such a moment at work:

“I was about to walk into a meeting that I needed to attend, and the only chair that was available was between two men. I didn’t turn around and walk out, but my body turned around and walked out. And I couldn’t talk to save my soul because there was this battle going on about whether or not I should go into the meeting, and someone wanting some memory to come up and someone else suppressing it. I tried to walk into that meeting, but I couldn’t do it.”

In this one episode, Erika describes experiencing not only severe identity alteration (“someone wanting some memory to come up and someone else suppressing it”), but three other dissociative symptoms as well. Her identity confusion is expressed in terms of ambivalence about entering the room: the part of her that felt vulnerable about having to sit between two males in the meeting—possibly an alter personality with memories of the abuse—impelled her to perform an action that another part of her resisted. Her depersonalization is expressed in terms of “my body walked out,” and her amnesia in terms of “suppressing” the memory that wanted to come up. This interdependence of symptoms is typical in DID.

The names people give their alters are sometimes the usual ones, like “Tommy,” “Susan,” “Joan,” or “Joe,” but they can also be symbolic names suggestive of split-off parts of their personalities or partially disowned capacities, like the “Commander,” the “Nurse,” the “Wise One,” or Erika’s the “Professional.” Alters cover a wide age range, from infants to the elderly, often representing the person at different ages, including ages not yet attained. Some “guru” alters who represent internal helpers, guides, or counselors may be thought of as ageless or timeless rather than as having a specific age and may be modeled after religious figures who are not necessarily of the persons own faith. Many people can envision facial and other physical characteristics of their alters and delegate skills to one alter that the other alters or the primary personality doesn’t share and can’t perform when that alter isn’t out. In addition, an alter in control may make friends without the person’s awareness, so that he or she is unable to recognize the “friends” at a later time. The tendency of a multiple to refer to herself as “we,” as Erika did, gives an indication of how it feels to have a group of markedly diverse individuals living in one body.

In some instances a person with DID will associate the different names of alters with particular actions or feelings. “Sally will have sex,” says a law student, describing the different lives of Sally, Andrea, and Cindy, three of her four alters: “Sally eats. Sally grocery shops. Sally has friends at the law school. Sally has had a relationship, a friendship, with some junior professor from the law school. Andrea went to school, you know college. Cindy burned me with a cigarette lighter.”

Switching personalities often occurs in a trancelike state. If the person is aware of it, the anxiety can be overwhelming. One woman, who refers to the childish parts of herself as her “kids,” says that she has something like a “town meeting” with her alters from time to time to calm herself down after a disturbing switch. “If one of the kids mouthed off, say, or did something out of line, we’d all sit there and figure what we’re going to do to repair the damage. Then we’d choose which personality was best to cope with the situation, and they’d go out and try to take care of it.”

As a result of the amnesia that often accompanies their dissociative episodes, multiples may find themselves with articles they don’t remember purchasing and don’t even like that were bought when one of their alters was out. “I have clothes in my closet that I wouldn’t be caught dead in,” says a young woman, bemused. “I have a ton of silver jewelry, and I hate silver. I like gold, and I have a lot of silver, like American Indian pieces and stuff like that. I have a china teacup collection, and I don’t believe in collecting things; they collect dust. These things are all over. But I keep them. I can’t get rid of them.”

This unexplained possession of articles in DID is different from the nasty surprise that can be a feature of compulsive shopping. Shopaholics are essentially people who use shopping as a form of mood alteration. Many of them are surprised or shocked by the contents of their closets when some circumstance—usually the cancellation of their credit cards or confrontations with family members—forces them to recognize that they have a compulsive disorder. The surprise is caused by the number of objects they’ve purchased or the amount of money they’ve spent, not the nature of the items themselves. Although dissociative disorders and compulsive disorders overlap to some degree—a person can have an alter who is a shopaholic—the disorders are not identical. The person with bipolar disorder who goes on a buying spree during a manic phase doesn’t have amnesia for the purchases, only a disregard for their cost.

Another sign of severe identity alteration that can startle someone is finding written evidence of some kind—letters, notebooks, diaries—attesting to the presence of alter personalities. These items can range from documents in a different handwriting to poetry or prose in a language the person doesn’t remember studying. A woman who has never studied French, for example, may be mystified to find herself fluent in that language because an alter personality either studied it or picked it up from a French relative or friend without the woman’s conscious awareness.

After suffering a miscarriage, a medical writer diagnosed with DID received a publication in the mail that she had written yet initially failed to recognize as hers. “An envelope came with copies of this pamphlet naming me as the author,” she says, “and I didn’t remember anything about having written this pamphlet. I was really upset. I read it, and sure enough it was my style. I had a chapter in there about miscarriage, and I know that when I wrote it I said, ‘Hmm, I wonder if they’re gonna think this is too intimate and toss it out.’ And when I saw the word miscarriage in there I realized, yes, I did write this booklet.”

In most cases, a person experiencing severe identity alteration knows of this symptom primarily from reports from others. “Sarah is vicious and Terry is mean,” says Randy, a twenty-seven-year-old dental technician diagnosed with DID. “Frank, my friend, told me, ‘Just let me know when Sarah arrives. She has a black belt in karate, and I don’t want to deal with it.’ I feel really stupid about that. I mean, how can your friend tell you that you have a black belt, and I don’t even know karate? I’m not very athletic either.”

Although many people with DID experience only subtle vocal and behavioral changes when an alter personality emerges, when someone else notices these changes they can be embarrassing. Randy recalls being observed by a stranger when two of her alters got into a heated argument while she was driving her car. “I made a decision not to see the doctor because it was snowing, the roads were horrendous, trucks couldn’t move. I went to a pay phone, called up and canceled my appointment, and got back into the car. Suddenly the one I call Sarah started yelling out loud that we had to go see the doctor. And I calmly told her, ‘No, we don’t have to go,’ and then she started screaming again. There was a man in a truck or car who looked. And his eyes caught my eyes, and I realized that he could hear them.”

People who are unaware of having alter personalities may believe that their friends or relatives are playing a very unfunny game with them and may react to the feedback with anger or annoyance. Cassie, a nineteen-year-old college student who was diagnosed with a dissociative disorder on the SCID-D, said during her interview, “You begin to wonder who your friends are. You think they’re ‘gaslighting’ you. They’ll say, ‘Yesterday your name was Renee,’ or whatever, and ‘Your hair was done in a punk style.’ It’s freaky to me because it’s like, ‘What do you mean?’ I didn’t remember doing it. I had no idea that I was using different names or acting differently. It’s like a big joke, a joke that I don’t find amusing.” Asked whether she thought her friends were teasing her, she replied, “Well, they are my friends, but I have two choices. I can either choose to believe they’re pulling my leg or choose to believe I’m nuts.”

Cassie’s conclusion that someone with DID symptoms has to be “nuts” shows how badly we need to destigmatize dissociative disorders and counteract the defensiveness that is holding countless people back from getting the help they need. One young woman in the SCID-D study revealed how monumentally defensive a person can be when she spoke about the psychiatrist who originally diagnosed her with DID. “I thought he was getting extremely frustrated trying to explain the situation to me about multiple personalities,” she said. “He’s sitting there insisting that that was what my problem was and that unless you believe it or accept it, you can’t be cured. It’s like having a doctor tell you you’re dying, but you feel perfectly well. Just because this guy is supposed to have a degree, and he has no obvious reason for telling me something that wouldn’t be true, you don’t have to accept it. And I choose not to.”

When I corroborated her psychiatrist’s diagnosis, she said, “You can sit there and tell me something about being—like having a split personality—and to me that’s being totally imperfect. If I had to sit there and listen to you and believe you, then I couldn’t survive. It’s not something that I can accept or deal with.”

What if this same patient had been told that she had pneumonia? Would her attitude have been the same? Knowing that her illness was treatable and that she had a good prognosis for recovery, would she have said, “If I had to accept or deal with this illness, I couldn’t survive”? Not if she wanted to survive. If she did, she’d have accepted the diagnosis and done everything medically possible to help her recover. A dissociative disorder is no different from any other physical or psychiatric illness. With the willingness to accept the illness and get the proper treatment for it, patients have a good prognosis for recovery within three to five years. Conversely if the illness is undetected or is treated incorrectly, the person can go through many hospitalizations, spend years in treatment with no significant improvement, and suffer dire consequences.

Besides the depression and anxiety associated with an undetected or mistreated dissociative disorder, the impact on a person’s employment and personal relationships can be ruinous. Antisocial acts committed in a state of severe identity alteration or dissociative fugue range from shoplifting and destruction of property to child abuse and homicide. At their worst hostile alters may thrust a person into debt, alienate the person’s friends or intimate partners, place the person in a situation in which rape or physical assault at the hands of a stranger is likely, or impel the person to self-mutilate or attempt suicide.

In order to survive massive abuse in childhood, people with DID have had to carry dissociation to its outer limits, subdividing themselves into a number of separate personalities with isolated memories and feelings. Their secret inner world is plagued by all of the five symptoms. Parts of their past, even all of their growing-up years, have vanished into the black hole of lost memories, leaving them vulnerable to vivid flashbacks or puzzling gaps in memory that steal unaccountable stretches of time from their lives today. Some feel a profound disconnection from their bodies, floating outside them and observing themselves from a distance or experiencing parts of their bodies as changing shape or size. Others are so detached from their emotions that they feel as if they’re walking through life like actors in a movie, distant and robotic, sometimes compulsively cutting their own flesh to relieve their terrifying anxiety and feelings of inner deadness. They may perceive the world around them as unreal or unknown—strangers in a strange land even when they’re at home with their families. Some have feelings of confusion or conflict about who they are, even whether they are male or female. And finally there are those—the ones the TV talk shows love to exploit—whose identities have splintered off into a multilayered rabble of separate parts, each holding different fragments of the “host” and engaged in a harrowing tug-of-war within.

Even in these extreme cases, DID is highly amenable to treatment. The remarkable success that many patients have had in overcoming DID is an inspiration to everyone struggling to heal childhood wounds.

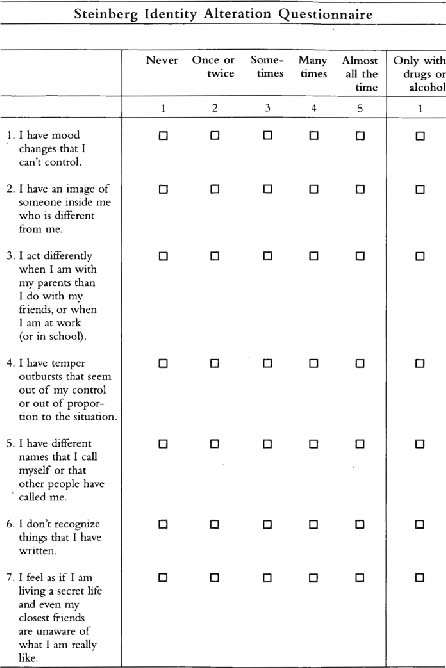

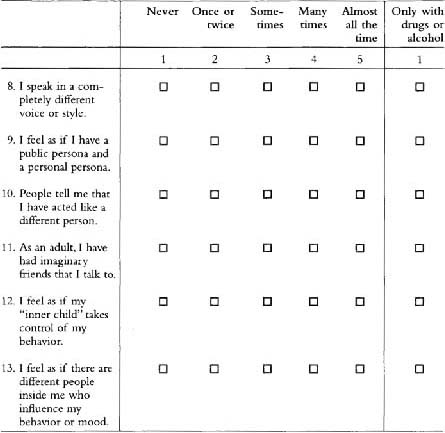

The following questionnaire will help you identify what symptoms of identity alteration you are experiencing and whether they are mild (normal), moderate, or severe.

If you have had any of the above experiences, answer the following:

To Score Your Identity Alteration Questionnaire:

Assign a score of zero to the following items: Normal items: #3, 9.

For all other items, assign a score ranging from 1 to 5 corresponding to the number on the top line above the box that you checked.

Now add up your score. Use the general guidelines below for understanding your score.

OVERALL IDENTITY ALTERATION SCORE

| No Identity Alteration: | 11 |

| Mild Identity Alteration: | 12–20 |

| Moderate Identity Alteration: | 21–35 |

| Severe Identity Alteration: | 36–55 |

RECOMMENDATIONS

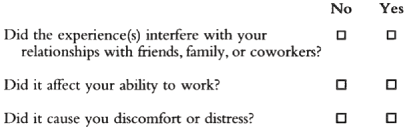

If your total score falls in the range of No to Mild Identity Alteration (11–20), this is within the normal range unless you have experienced item #6 or 13 recurrently. If you have experienced these items several times, we recommend that you be evaluated by a professional who is trained in the administration of the full SCID-D interview.

If your total score falls in the range of Moderate to Severe Identity Alteration (21–55), we recommend that you be evaluated by a professional who is trained in the administration of the full SCID-D interview. If your identity alteration has interfered with your relationships with friends, family, or coworkers or has affected your ability to work or has caused you distress, it is particularly important that you obtain a professional consultation.

Should an experienced clinician find that you have a dissociative disorder, you have a treatable illness with a very good prognosis for recovery. Your illness is widely shared by others who coped with trauma by using the self-protective defense of dissociation. With proper treatment, in time, you will be able to integrate the memories and feelings of your separate parts. Eventually, as you grow strong enough to reconnect with your hidden memories and feelings and accept them as your own, your identity alteration will be reduced and you will become a more integrated and psychologically healthy person.