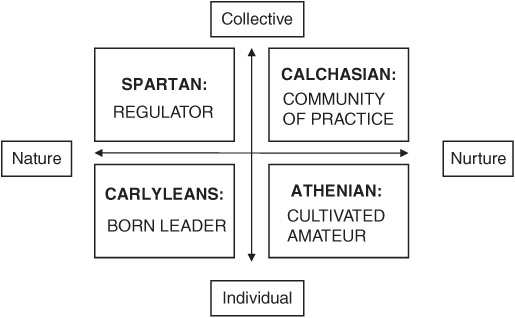

‘Are leaders born or bred?’ is probably the question that I am asked most frequently when teaching. My response is usually some variant of ‘both’: we really don’t know enough about this to make any categorical statements one way or the other (though that doesn’t stop people). What I want to do in this chapter is explore the question by generating a fourfold typology that expands the premise from ‘nature or nurture’ to include ‘collective or individual’. This is not to sidestep the question but to be clear that any answer depends upon what kind of leadership we are talking about. We will start with the most traditional response: leadership is both individual and natural – Carlyle’s approach – then consider a nurtured variant of this individualist approach, originally located in Athens. We then switch to consider collectivist approaches, beginning with the Athenians’ ‘natural’ nemesis – the Spartans – and concluding with the Calchasian – the nurtured collectivists in a community of practice. A model of this typology is reproduced in Figure 11.

Shown in Figure 12 are two photos that relate to the question ‘are leaders born or bred?’ The first is of a school group in Georgia and the ringed figure is the young Stalin. The second is of a school group in Austria and the ringed figure is Hitler. The similar positioning of these two individuals in places of leadership – in the middle of the back row – is both alarming and coincidental. Stalin is the boy who organizes the photographer, takes the fees, and pockets the profits – he appears to be a ‘born’ leader. Hitler plays no part in the organization of the photo; indeed, he is almost invisible at school – a waster going nowhere. In fact, Hitler’s senior officer in the Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment, in which he served in the First World War, said of him at the time:

11. A typology of leadership development

Hitler did not cut a particularly impressive figure.… [but] he was an excellent soldier. A brave man, he was reliable, quiet and modest. But we could find no reason to promote him because he lacked the necessary qualities required to be a leader… When I first knew him Hitler possessed no leadership qualities at all.

(quoted in Lewis, 2003: 4)

Yet, within the space of a few years, Hitler turned into one of the most influential leaders of the 20th century. How did this happen? There are claims that Hitler – who was gassed by the British towards the end of the First World War – was taken out of the line and, along with many of his colleagues, proclaimed himself permanently blinded. But while all the other soldiers insisted on being demobilized, Hitler demanded to return to the front. Now, since none of the soldiers were permanently blinded, the authorities knew most were literally trying to pull the wool over their eyes to escape a lost war, but they assumed that Hitler was suffering from some form of mental illness so he was sent to a psychiatrist. That psychiatrist, in turn, proclaimed that Hitler would only ever regain his sight if he was the ‘chosen one’ sent to save Germany. The story then unfolded with Hitler’s returning sight and his gradual ‘understanding’ that destiny had saved him for something greater than being a corporal in the army. Whether this particular episode is true or not is not as important as considering the numbers of leaders who have achieved extraordinary things as a consequence of their belief in some form of destiny. Whether that destiny is one foretold by god (Jean d’Arc, Oliver Cromwell, Martin Luther King, Florence Nightingale) or by some force of history (Genghis Khan, Nelson, Stalin, General Patton, Winston Churchill) is less critical than its effect: it seems to generate a level of self-confidence that facilitates inordinate risk-taking, both of which are understood by followers as manifestations of great leadership. Of course, many of these ‘predestined’ leaders take risks and die in the process of their execution – but we don’t get to hear about them. Instead, it is only the successful ones who survive, and these are the ones who bewitch us with their tales of destiny. In these cases, the question ‘are leaders born or bred?’ is actually redundant, because they may have been born ‘ordinary’ but have become transformed into ‘extraordinary’ by some kind of experience. But how important are these kinds of leaders?

12. Stalin and Hitler. Stalin in his Tiflis seminary school (above) and Hitler in his Leonding school photo (below)

Thomas Carlyle (1795–1881) was adamant that ‘true’ leaders -heroes – were born not made. The masses – who were ‘full of beer and nonsense’ – were incapable of generating their own leaders and the new capitalist bosses – ‘the millocracy’ – were only interested in the accumulation of material wealth. For Carlyle, great leaders did not emerge through privileged enculturation or education but through individual raw – that is, ‘natural’ – talent combined with a Nietzschean ‘will to power’. Carlyle’s heroes were ‘born to lead’ but not ‘born into greatness’; hence his list included Mohammed, Luther, Frederick (who became) the Great, Cromwell, and Napoleon – all (like himself) born with little except the ‘natural will’ and ability to lead. For, as Carlyle insisted:

Universal History, the history of what man has accomplished in this world, is at bottom, the History of the Great Men, these great ones; the modellers, patterns, and in a wide sense creators, of whatsoever the general mass of men contrived to do or to attain; all things that we see standing accomplished in the world are properly the outer material result, the practical realization and embodiment, of Thoughts that dwelt in the Great Men sent into the world: the soul of the whole world’s history, it may justly be considered, were the history of these.

(Carlyle, 2007: 1)

Carlyle would probably have been sympathetic to contemporary evolutionary perspectives on leadership – a response mechanism to the problem of coordination in an era when survival required collective action for gathering food and protecting the group. The current activities of hunter-gather societies are probably the closest we can get to early models of human leadership during the Pleistocene era (roughly from 1.8 million ago to 10,000 years ago, the end of the last ice age) where semi-nomadic, kin-related groups of 50–150 Homo sapiens operated, probably spreading from their origins in Africa about 200,000 years ago. The development of settled agriculture after the end of the last ice age generated significant reserves and resources that may have generated a propensity to abandon both hunter-gatherer cultures and the egalitarian and participative leadership models that are associated with their contemporary variants. In short, the production of surpluses may have triggered the move to more static communities led by warlords whose ability to protect/exploit their communities -and destroy rivals – may have been what Hobbes had in mind when he talked about the war of all against all when life was ‘nasty, brutish, and short’.

For evolutionary biologists, the selection of leaders under conditions of constant war would have focused upon a relatively small number of ‘alpha-males’ – Carlyle’s ‘heroes’. The subsequent forms of natural selection eliminate all but the fittest, or rather all but the most appropriate for leadership positions, but this also means that contemporary organizational forms are deemed to be ‘inappropriate’ for our (hardly) evolved forms of leadership. In effect, in this approach the requirements of leadership are hardwired into humans and remain relatively stable across space and time.

Actually establishing what is or isn’t hard-wired is extraordinarily difficult to do. First, it’s quite difficult to assess people before they become affected by their upbringing – evaluating babies for their leadership skills is not easy. Moreover, some behaviours seem illogical: why, for instance, would you voluntarily subordinate yourself to a leader if the consequences for reproduction advantage the leader more than the follower?

Often, this approach relates the apparent universality and timelessness of human leadership to our animal nature because leadership in animals appears unchanging and tends to be amongst the most hierarchical and brutal. Leadership amongst lions, for example, is primarily undertaken by lionesses in terms of hunts and tending the young but the alpha-male dominates others in terms of eating and mating privileges. But not all animals have the same leadership patterns: in spotted hyenas, for instance, the gender roles are reversed – females are larger than the males, and it is the former who control the mating process and lead the group; males do most of the hunting, but females dominate the males and have priority access to kills made by the males. Some evolutionary approaches imply that the matriarchal domination of spotted hyena groups develop because the males play no role in bringing up the young; strange how no-one told the cheetahs this leadership strategy. Wolf packs are slightly different: family units of between two and twelve individuals are led by the alpha-pair which alone breeds. A strict hierarchy exists within wolf packs in which the alpha-male leads hunts and territorial defence while the alphafemale leads the pups.

But if human leadership is a mirror of the animal world, then we should most closely resemble the world of chimpanzees, our closest genetic cousins. Yet De Waal’s account of chimpanzees suggests that leadership is not determined by size or necessarily by hardwiring but by coalition-building between dominant males supported by senior females. Moreover, Boehm suggests that analysis of contemporary hunter-gathers suggests that leaders are always and everywhere resisted by ‘reverse dominance hierarchies’ – by coalitions who unite temporarily to resist tyrants. In effect, the legitimation of leaders depends upon the followers, not the leaders.

If we really are the ‘victims’ of our genes, then we might also want to question the notion of free choice or agency. Volition is the exercise of free will or conscious choice, as opposed to determinism, hence, if human action is determined by biological genes, then the intentional element of leadership is removed and we may have a problem in determining individual responsibility. In effect, we may have no responsibility and therefore no leadership. In fact, taking this approach to its logical conclusion in the case of biologically inherited characteristics would be to suggest that those leaders with ‘criminal genes’ are not responsible for their leadership of criminal gangs, even if the results are significant in terms of people killed or money stolen and so on. And if we insist that action is determined by biological requirements over which individuals have no volitional control, then we might even consider looking for the leadership gene that is making them act. The ancient Athenians would have had none of that; for them, leadership was something to cultivate not something to emerge naturally.

The ‘Athenian’ refers to the model of leadership learning embodied by those citizens of Ancient Athens (male only) who acquired leadership position by dint of their relatively high social birth combined with a liberal education in the arts, suitably supported by ‘character-building’ physical education. The initial schooling period was from eight to fourteen years old, and richer boys then progressed until eighteen, when a two-year military service was the norm. The intention was to nurture (male) children, who through engagement in reflective learning, often in private, would provide the next generation of Athenian citizens with sophisticated and responsible leaders. These leaders regarded themselves as ‘cultivated amateurs’ – they were not the products of a sausage-factory educational system that poured forth professional soldiers like their arch-rivals the Spartans – but instead the most civilized product of the most civilized society. That the presence of slaves and the subordination of women might strike the contemporary reader as anything but civilized is another matter.

The consequence of this kind of ‘cultivated’ approach to leadership training in the British Army through the 19th century was an upper-class officer corps devoted to loyalty, hard work, and practicality – but little or no capacity for imagination and little interest in or support for science and technology. Thus its difficulties in the early part of the First World War, and the 1930s in particular, and the decline of Britain’s technological lead in general. And where business and stalemated war required entrepreneurial and imaginative thought, instead it generated ‘guardianship’, a code of ethics that favoured responsibility and romantic idealism over innovative structures, procedures, and strategies. The result was an indifference to military theory or strategy and reliance upon the individual initiative of combat officers together with good British ‘common sense’.

Leadership, then, was not something that subordinates might engage in – as the German Army had long been developing – but it was essentially rooted in an exchange mechanism: paternalism was exchanged for loyalty, dignity for deference. In effect, the leaders were obliged to treat their soldiers as they would their own children, and the soldiers would be obligated to obey their officers as in loco parentis in return. As one subaltern from the 1/King’s suggested in 1914: ‘How like children the men are. They will do nothing without us… You will see from this some reason for the percentage of casualties among officers.’ Hence privileges acquired by the officer corps were not necessarily resented by the soldiers – as long as the privileges did not undermine the social obligations of the officers to look after their men, and that often implied very small things, such as remembering a soldier’s birthday, enquiring about his home life, and making sure the soldiers were all fed as well as possible.

While the Carlylean and Athenian models are both essentially individualist leadership models, the former being natural and the latter being encultured, the Spartan is ruthlessly – if not obsessively – collectivist and overtly naturalist: leadership abilities were something that many Spartans were born with, but they had to be corralled to the benefit of the community, and they had to be enhanced in a collective framework. Moreover, leadership would only work effectively when the followers were trained into obedience through the same leadership system, regulated to follow the regulator. That regulation began at birth when a committee of elders assessed each infant, leaving those defined as ‘weak’ to survive or die on the slopes of Mount Taygetos overnight.

The Spartans placed all their male children from seven to eighteen years of age into the Agoge (agôgê) (literally, ‘raising’, as pertaining to animals), an institution that combined education, socialization, and training to turn boys into warriors. The content of Spartan education involved little reflective learning and the construction of loyalty to the state remained foremost. The primary aim of education for boys was the creation of a loyal, dedicated army, and at the age of thirteen they were commanded by one of the irens – twenty-year-old junior leaders whose experience in command was designed to instil Spartan leadership qualities amongst a large number of warriors. The younger boys were also required to go through the Krypteia, or ‘period of hiding’, when they lived alone or in small self-led groups living off the countryside and killing helots (Spartan slaves) who were regarded as particularly strong or likely to harbour leadership ambitions themselves. At the age of eighteen, a select group was appointed to the elite Royal Guard and thence to formal military leadership positions, though military training continued until the age of thirty. But even royalty in Sparta had a collective, rather than an individual, orientation: the five annual elected ephors – overseers – swore to support the dual kings but only if the kings maintained the rule of law. Thus, if one of the Spartan kings insisted on leading the army into battle, as he was permitted to do, two of the five ephors always accompanied him and reported back on his conduct.

The clearest connection to a more recent Spartan approach to selecting and collectivizing for leadership was probably the organizations making up the Hitler Youth movement. In the Adolf Hitler Schools, in particular, German boys were groomed for leadership on the battlefield and in the homeland. While one-third of Germans born between 1921 and 1925 died in the war, 50% of those attending the Adolf Hitler Schools died in the war. By 1935, 50% of all Germans aged between ten and eighteen were in the Hitler Youth, and 90% of all those born in 1926 were recruited. In fact, membership remained voluntary until 1939, but few resisted. Organized on military lines with groups of 150 comprising a company (Fähnlein) down to the ten-boy Kameradschaft (Jungmädelschaf for girls). ‘Leadership of youth by youth’ was Hitler’s slogan, and nothing was left to chance: 12,727 Hitler Youth (Hitlerjunge) (aged fourteen to eighteen years) leaders, and 24,660 Jungvolk (aged ten to fourteen years) (Jungmädel for girls) leaders were put through 287 leadership training courses in 1934 alone. Once through the course of physical and military training and ideological conditioning, these young leaders were provided with manuals for their own followers, complete with introductions, songs, and texts for each lesson. No discussion or dissension was permitted, but the most important experience seems to have been the weekend and summer camps where the community-building developed in earnest, usually by ensuring that everyone from the age of twelve took turns to lead his Kameradschaft or her Jungmädelschaft. ‘That way’, wrote a member of staff at a boy’s school, ‘he learns to give orders and gains the subconscious strength of self-confidence which is necessary in order to command obedience.’ After successful completion through the Jungvolk and Hitlerjunge, the chosen few went on to one of the Ordensburg (SS Colleges), where Sparta remained an ideal. ‘What we trainers of young leaders want to see’, said one trainer in 1937, ‘is a modern form of government modelled on the ancient Greek city-state. The best 5 to 10 per cent of the population are selected to rule, and the rest have to work and obey.’ These leaders in waiting then spent one year in the SS College at Vogelsang, learning ‘racial philosophy’, a further year at Crössinsee, ‘character-building’, and a final year in Sonthofen on administrative and military duties. It was at the 1935 passing-out parade that Robert Ley, the Nazi Party head of organization, commented:

We want to know whether these men carry in themselves the will to lead, to be masters, in a word: to rule. The NSDAP [Nazi Party] and its leaders must want to rule… we take delight in ruling, not in order to be a despot or to revel in a sadistic tyranny, but because it is our unshakeable belief that in all situations only one person can lead and only one person can take responsibility. Power rests with this one person.

(quoted in Knopp, 2002)

For the Nazis, the ultimate ‘one person’, of course, was Hitler, and as the war progressed Hitler distanced himself from the collectivist essence of Nazism and from the pre-war German military philosophy (Mission Command) that supported subordinate initiative and feedback between leader and followers, and this played an important role in his nemesis. For instance, it is clear that from 1939 to 1941, the invasion of Poland, Western Europe, and the USSR, that Hitler engaged in conversations with his generals and listened to them – even if he did not always take their advice. And only on one occasion did Hitler personally intervene in the invasion of Poland – to be overruled by Von Rundstedt. However, once the invasion of the Soviet Union faltered in the winter of 1941, Hitler began ‘micro-managing’ the armed forces and stopped listening to his generals. Thus, as the war progressed, Hitler’s conversations became increasingly one-sided and the information he received stopped coming from constructive dissenters and instead came from destructive consenters. That is to say, as the independent thinkers were removed from his circle of advisers, so the quality of the advice sank to the point where the only advice he received was that they thought he wanted to hear rather than that which he needed to hear.

In contrast, Winston Churchill, who began the Second World War in the admiralty and removed a certain Captain Talbot because he had the temerity to disagree with Churchill about the anti-U-boat strategy, began as prime minister by recruiting many of the individuals he knew to be the most independent and free-thinking. Hence, he asked Ernest Bevin, one of the leaders of the General Strike in 1926 that Churchill had sought to crush, to join the war cabinet as Minister of Labour and National Service. Indeed, he even worked with Chamberlain and Halifax, two of his bitterest political enemies. Similarly, in the military sphere, Churchill retained Alan Brooke despite their famous disagreements and furious disputes, because Churchill recognized that only such people had the fortitude – and stubborn independence – to give him the honest advice that he needed. This alternative way of learning to lead is a critical element of the fourth model of learning: the Calchasian.

The fourth leadership learning form – the Calchasian – combines a collective orientation with a nurture philosophy. In effect, it suggests that leaders are neither omniscient nor omnipotent, and therefore leadership has to be distributed through the organization; furthermore, such a deep or distributed approach can be encultured, it can be socially supported and we need not simply rely on ‘nature’ to take its course in the leadership stakes. This kind of approach also assumes that engagement in social practice is the fundamental process by which we learn, thus learning is a collective or social activity not an individual activity. Indeed, as Wenger has suggested, learning actually occurs through a ‘community of practice’ in which engagement in a social practice constitutes a social community and thus an identity which can then be led.

Since the beginning of history, human beings have formed communities that accumulate collective learning into social practices – communities of practice. Tribes are an early example. More recent instances include the guilds of the Middle Ages that took on the stewardship of a trade, and scientific communities that collectively define what counts as valid knowledge in a specific area of investigation. Less obvious cases could be a local gardening club, nurses in a ward, a street gang, or a group of software engineers meeting regularly in the cafeteria to share tips.

(Wenger, quoted in Grint, 2005: 115–16)

But a community of practice does not arise simply from physical proximity, and unless there is ‘mutual engagement’ of participants, that ‘community’ will not develop a ‘community of practice’. Moreover, a community of practice is not a utopian ideal where mutuality and love prevail, but one defined by shared practice and collective repertoires rather than harmonious relationships.

I want to suggest, further, and in an inversion of our common assumptions about this relationship, that it is followers who teach leadership to leaders. In effect, it is not just experience that counts, but reflective experience. This inverse learning is mirrored in the way most parents learn to be parents: their children teach them. Or as Gerard Manley Hopkins suggests, ‘The child is father to the man’. Hopkins seems to be implying that the male child will literally grow into the man, in the same way that an acorn grows into an oak tree. But I want to suggest a different interpretation here: that the child teaches his or her progenitors to be parents.

Although many books exist on parenting, a large proportion of learning to be a parent can only come from the experience of ‘parenting’. After all, you cannot know whether somebody else’s method works until you try it on your own child. In theory, parents teach their children how to act as children, but of course the latter have a way of ignoring much of this worthy advice. If this was not the case, then no parent would ever have misbehaving children, no child would have a tantrum on the supermarket floor, no teenager would experiment with alcohol or drugs, and none would come home late or leave their room looking like a burglar has just ransacked the place. Since this does occur regularly, the superior resources of parents (physique, language, legal support, moral claims, source of pocket money, threats of grounding, and so on) have only limited effect. The critical issue, then, is that parents have to learn how to be parents by listening and responding to their children. In effect, we are taught to be parents by our children: if they don’t feel comfortable with the way we are holding them as infants, they cry and we adjust our hold; if they are hungry, they cry and we feed them; if they are tired, they cry and we rock them to sleep. And when – not if – we get it wrong (or they think we get it wrong), they tell us, by crying or struggling or sulking or whatever. Of course, we then have to decide what to do, whether to ‘teach them’ some self-control or whatever, but whether that works or not is not solely in our control, and we often have to negotiate our way through this continually changing relationship. Indeed, although experience might make parenting easier – the more children you have, the easier it might become – this need not be the case, perhaps because each child–parent relationship is different, and/or because each new child alters the pattern of prior familial relationships, and/or because some people have problems learning.

What might be crucial here is the extent to which parents receive feedback from their children. It may also be that parents learn most from relationships with their children that are not hugely asymmetric. In other words, when children are dominated by their parents – or vice versa – neither side in the relationship necessarily learns much or matures. Indeed, it may be that one of the reasons why so many parents do seem to make a relatively good job of a very difficult task is because children are often more open and honest in their feedback than adult followers or subordinates: if parents are not doing something ‘properly’ – as defined by the children not by the parents – the parents will soon hear about it. This is evident both with toddlers, who can be excruciatingly honest in their conversations, and when we meet the children of people we perceive as formidable leaders: so often, their children seem capable of saying things to them that we poor followers dare not even think about saying to them. If we map this learning model onto leadership, the implication is that, while leaders think they are teaching followers to follow, in fact it is the followers who do most of the teaching and the leaders who do most of the learning. Here, then, we might reconstruct Gerard Manley Hopkins: ‘The follower is teacher to the leader.’

Inevitably, some leaders fail to learn and some followers fail to teach, but it may well be that one of the secrets of leadership is not a list of innate skills and competencies, or how much charisma you have, or whether you have a vision or a strategy for achieving that vision, but whether you have a capacity to learn from your followers. And that learning approach is inevitably embedded in a relational model of leadership. I also want to suggest that the asymmetrical issue is critical to successful leadership. That is to say, where the relationship between leaders and followers is asymmetrical in either direction – weak/irresponsible leaders or weak/irresponsible followers – then success for the organization is likely to be short-lived because feedback and learning is minimized. In effect, learning is not so much an individual and cognitive event but a collective and cultural process.

As I intimated above, this problem of learning to lead from one’s subordinates is not a novel idea and has, in fact, been evident in leadership since the Classical era. In Greek mythology, for instance, Calchas, the son of Thestor (a priest of Apollo) is a soothsayer to Agamemnon, King of Mycenae, in the Trojan War. Agamemnon, concerned to ensure success, approaches Calchas – a Trojan. Calchas then visits the Oracle at Adelphi and declares that victory for the Greeks can only be achieved at significant cost to Agamemnon: the sacrifice of his daughter Iphigenia, the task will take ten years, and no victory will ensue unless Achilles fights for the Greeks. Agamemnon, therefore, has to take on trust the words of a Trojan – a former enemy – because he cannot trust the information of his ‘natural’ allies, the Greeks.

This ‘Calchasian’ approach thus transcends one of the most critical weaknesses of leadership learning: the displacement of constructive dissent with destructive consent. By this, I mean that since no individual leader has the knowledge or power to lead effectively, leadership must be a collective affair. However, as leaders progress through organizational hierarchies, they tend to surround themselves with sycophants – the veritable ‘yes-people’ who provide flattering feedback rather than honest feedback. In contrast, long-term organizational success requires constructive dissenters – individuals able and willing to provide formal leaders with potentially unpleasant but necessary feedback for leaders to learn how to lead. Agamemnon’s problem is that only a non-Greek can provide this, and that provides a manifestation of the central problem for learning to lead: it requires those who are willing to stay out of the limelight, avoiding the individual heroic model of leadership beloved of Carlyle and the like, but simultaneously do a job that is in many ways ‘heroic’ by providing formal leaders with contrary advice, by refusing to be cowed by the authority of formal leaders, and by putting the needs of the community or organization before their own – an approach much closer to the leadership model employed by some American Indians.

So the issue is not ‘How should an organization find a leader who does not make mistakes’, but what kind of organization generates a supporting framework that prevents leaders making catastrophic mistakes and ensures that the organization learns from the mistakes that we all make. Not ‘Who should lead us?’, but ‘What kind of organization do we want to build?’ and ‘How can we build it?’ The assumption that failure is a critical component of learning also implies that we should develop leaders by putting them in difficult situations where risks are necessary, errors possible, and learning essential. Or, as the saying goes: ‘Good judgment comes from experience and experience comes from bad judgment’ (attributed to various people, including Mark Twain and Frederick P. Brooks). So do we have to design more opportunities for failure into learning to lead? Perhaps Piet Hein captures this approach best with his marvellous poem and cartoon, shown in Figure 13.