According to Gladwell, Warren Harding, the 29th President of the USA, is also widely regarded as the worst President in US history. Three years of his administration achieved little, and Senator William G. McAdoo said that a typical Harding speech was ‘an army of pompous phrases moving over the landscape in search of an idea’. After Harding left office, it became clear that scandal and corruption were never far away – yet during his tenure he remained popular. Gladwell suggests this relates to a common temptation to relate first impressions of physique and personality to potential success. Since Harding was the archetypal tall and handsome (T&H) leader, and a confident (if vacuous) speaker, people naturally attributed great things to him in the same way that we attribute organizational success to individual leaders, often with little or no evidence that the correlation is actually a causation. In fact, there are strong correlations between body and attributive assumptions. For example, Gladwell’s own analysis of Fortune 500 companies found that most of the CEOs were white males with an average height of just under six feet. In fact, almost 60% were six foot or taller, compared to a mere 15% of the rest of American adult males. So can we start by assuming that most Western leaders seem to be tall handsome white males, or THWMs?

Not necessarily. Despite the common assumption that height makes a significant difference to how leaders are perceived (the taller, the better), there have been lots of small leaders. For example, Ben Gurion and Deng Xiaoping were all 5 foot (1.52 metres); Yasser Arafat, Mahatma Gandhi, Kim Jong-il, King Hussein, Nikita Khruschev, and Dmitry Medvedev are or were all 5 foot 3 inches (1.6 metres); and Queen Elizabeth II, Franco, Haile Selassie, Silvio Berlusconi, Emperor Hirohito, Nicholas Sarkozy, Stalin, T. E. Lawrence, and Horatio Nelson are or were all under 5 foot 6 inches (1.66 metres). On the other hand, American research has consistently shown that taller people earn more than smaller people – in 2007, each extra inch of height was correlated with an extra 1% increase in income, and people with lighter skin colour earn more than those with darker skin colour.

Despite this, there are, and always have been, significant female leaders who have broken the male mould. There are, for instance, at the time of writing, 23 female heads of state from the 192 countries affiliated to the United Nations, and there were queens ruling Egypt in 3,000 BC. But these are often exceptions that prove the rule of male dominance across space and time.

So what kinds of characters do leaders seem to be now? Kaplan’s analysis suggests an even more stereotyped model – CEOs are not just THWM but also archetypal alpha-males: aggressive, efficient, persistent, privileged, and uncompromising. So we can change our acronym now to tall handsome white alpha-males (of) privilege, or THWαMPs (which is easier to say than THWMs). Yet Kaplan’s data are derived from CEOs of private equity firms… the very arena that seems to be mired in financial disaster as I write. Perhaps this personality type explains why, according to Andrew Clark, five days after the world’s largest insurance company, AIG, accepted an $85 billion emergency loan from the US government to stave off bankruptcy (17 September 2008), the company spent $440,000 on a week-long corporate retreat at one of California’s top beachside resorts. Or, as Henry Waxman, chair of the US Congressional Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, said to Richard Fuld, then CEO of Lehman Brothers, on 8 October 2008: ‘Your company is bankrupt and our economy is in a state of crisis. Yet you get to keep $480m. I have a very basic question: Is that fair?’ The following day, AIG was granted access to a further $37.8 billion from the US state; it must have been a great party. In fact, the party must still be in full swing: in 1999, the average ratio of CEO to employee pay in the UK rose from 47 to 128, with Bart Becht, CEO of Reckitt Benckiser, topping the show at 1,374 (Becht received £37 million in 2008, whilst the average employee salary of the Slough-based multinational was £26,700 – the UK’s national average). Not that Becht needed to fear isolation: the average pay of the top 25 FTSE 100 directors in 2007/8 was over £10 million (as quoted in The Guardian).

Now the real issue here is not about fairness, if the implication is that treating followers as fellow humans rather than corporate resources is the way to lead successfully. That patently is not the case. There are lots of examples of success being driven through monstrous behaviour, by extraordinary cruelty, by slavery, and by many other ‘unfair’ leaders. Perhaps the point is twofold. First, fairness is only an appropriate criterion for judging leaders in contexts that are culturally associated with fairness. In crises, for example in war, survival is probably more important to most followers than fairness. But when the financial crisis struck the global markets in October 2008, the prior assumption about the importance of corporate success over fairness was reversed, and one of the reasons for the delay in passing the rescue package through the US Congress was because it was perceived to be unfair – to favour the bankers who had allegedly caused the problem at the expense of the tax-payers who were expected to rescue the bankers from their own mistakes. Second, returning to Chapter 2, we might suggest that the kind of leadership that works depends on (1) what the situation appears to require, and (2) how persuasive those same leaders can be in framing and reframing the situation so that it seems to call for the actions they themselves propose.

In many countries, fairness is often linked to diversity, yet in most of these same countries the level of diversity at the top is often marked by – diversity. For example, a poll by the Observer newspaper in October 2008 listed the top 100 most powerful black people in the UK, and the selection panel appears to have avoided the stereotypical listing procedures that would have filled the list with black pop stars and sports personalities. Instead, the selection was based on their ‘influence’, defined as: ‘The ability to alter events and change lives.’ Top of the men’s list was Dr Mo Ibrahim, the entrepreneur who did more than anyone else to bring the mobile phone to Africa. While the women’s list was headed by Baroness Scotland, who at school was told by a careers’ adviser that being a supervisor at Sainsbury’s was about her limit. She was the first black woman in Britain to become a Queen’s Council (QC), and in 2007 became the first female Attorney General. As Trevor Phillips, Chairman of the Commission for Equality and Human Rights, and fifth on the men’s list noted:

It’s important to show that there are people from minority communities who are playing a role in public life, ready to shoulder some of the burdens of the whole community, not just the narrow minority interest… There are two stereotypes: angry black men and suffering black women, and actually most of us are neither of those things. If people can stop thinking of black people they meet as fitting one of those two stereotypes, they might look past the front page, which is their colour, and look at the individual rather than think of them as a category. This kind of exercise helps to do that and will make a huge difference to a lot of people’s lives.

In the USA, with Barack Obama currently in the White House, people of colour in 2008 comprised about one-third, or 34%, of the population. But as a proportion of the top elected government officials, such as Members of Congress, only 15% are African American, Latino, Asian American, or American Indian, and only 24% are women. Things are little different in non-profit organizations, 84% of which are led by whites. Moreover, 42% of non-profit organizations serve only white communities. Traditionally, we have been led to believe that the problem is actually one best understood historically – of course, Western leaders used to be white men, but this is changing, albeit slowly, and soon we will see the emergence of greater diversity amongst out executive elite. Yet this is not at all self-evident.

Research undertaken by the Co-operative Asset Management in 2009 revealed that only 3% of the FTSE 350 companies had a woman as CEO (only four, or 1.3%, have female chairs), and 130 do not have any women at board level. Indeed, only 9% of board seats are taken by women – but it cannot be for want of an equal opportunities policy because 94% of the companies had them. In 2008, women occupied just under 10% of the board seats available on the top 300 European companies – but most of the limited growth that has occurred over the last few years can be explained not by the steady policies of diversity but, for example, by the legislative demands (from 2003) of Norwegian companies who are now required by law to have at least one woman on the board of all of its companies. In fact, Norway now has a 40% minimum target for all publicly listed companies. While the Scandinavian countries lead the gender equality movement, the rest of Europe lags some way behind.

In the USA, women represent half of those people in professional and managerial positions, but there is a familiar pattern beyond the general statement of equality: women tend to be better represented within charities and the public sector, but the higher up the ladder one looks, the fewer women are visible. For example, only 15 women are CEOs in the Fortune 500.

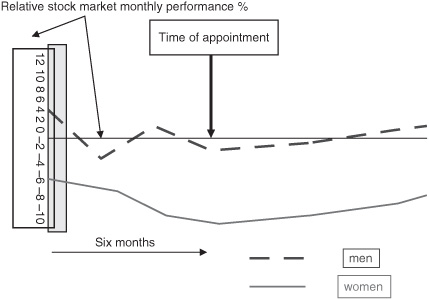

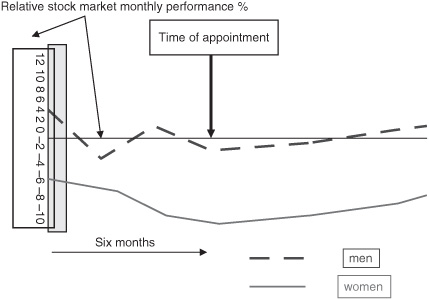

Of course, the absence of women from the boards of most companies may be less to do with male bias and more to do with this cold fact: there is a correlation between the proportion of women on the board and the weaker financial performance of the company. Now this might be because men make better accountants – though I doubt it – and however many accountants companies have (and the UK has proportionately more accountants than any other major competitor; the US has more lawyers), they do not seem to have saved many companies from the financial crisis of 2008. Instead, we need to focus on the word ‘correlation’ and distinguish it from causation, because the direction of cause is critical here, as Figure 14 suggests.

14. Women on the board and performance

What this figure implies is that women are appointed only when conditions are much worse than those that generally prevail for men’s appointments – which means that the task for women is much more difficult and that we can correlate poor performance with women – but it is the poor performance causing the appointment of women not the other way around. Indeed, in terms of performance of companies after appointment, there is proportionately little difference between men and women in many studies, though some suggest that gender diversity is positively correlated with success – at least provided the women on the board are well qualified, and Keohane notes that centuries of exclusion have provided women with a different set of questions to ask of our leaders.

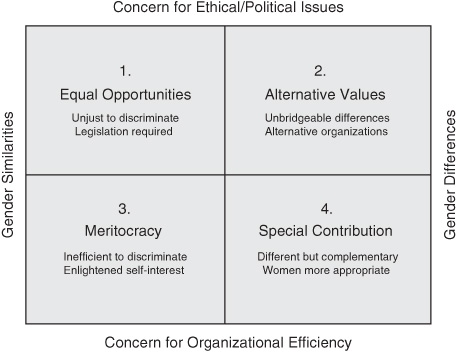

What should be done about the lack of diversity amongst our leaders? Well, that depends upon where you sit. If you are a THWαMP who wants to maintain that position, then clearly nothing needs to be done. But if you think something needs changing, then it still depends upon what you think the source of the problem is. Figure 15 reproduces Alvesson and Billing’s typology that addresses the issue of gender imbalance. Box 1 represents those people who assume that the genders are similar and that something should be done for ethical reasons. This often leads to a legislative approach, such as that undertaken by the Norwegian government that was mentioned before. Box 2 follows the same ethical line but suggests that the genders are essentially different and thus no legislative change can make any difference. The only real solution here is for women to set up alternative organizations, and indeed the proportion of new businesses set up by women does seem to be increasing as some women perceive the glass ceiling of traditional male-dominated organizations as impenetrable. Box 3 takes the genders to be essentially similar, but takes an efficiency rather than an ethical approach and argues that this makes the case for a meritocratic approach to save ‘wasting’ the talent of women. Last, Box 4 is efficiency-oriented but assumes the genders are different and focuses on the way women can make a ‘special contribution’ to organizations.

Now the point here is to recognize the connection between the explanation and the prescription, because this explains why different strategies for change are suggested – and, if they fail, why opponents of the strategy then try to reframe the problem in a different category. In fact, we wouldn’t expect there to be much difference between men and women because the genders are not markedly different in general measures of intelligence, nor in personality traits, and, if anything, women in Western Europe and North America are more often better qualified than their male counterparts. It would seem that the most important factors for explaining the differential success are actually the mundane features of asymmetric domestic responsibilities, sex discrimination, and gendered assumptions, and the stronger work networks of men that secure better access to more challenging positions and to better jobs. In effect, women (who tend to have stronger social networks than men) are expected to be more compassionate as leaders than men – and when they are, this behaviour is regarded as less robust than the more aggressive leadership expected of men. Of course, some women leaders adopt a more aggressive style, but these actions are often regarded as ‘inappropriate’. Either way, the odds are stacked against women leaders.

Of course, this also provides ammunition for those ‘I told you so’ moments, because we seem to make instant decisions about leaders or their strategies so that if we support them and they are subsequently successful, well, we knew they would be. And if they fail, well the situation must have changed, or someone must have undermined them, or some other excuse. This is not new. There is already a lot of evidence to suggest that instant responses to leaders (positive or negative) are very common. The selection of officers for the US Army during the First World War was premised on similar stereotypes: those applicants who were perceived to have attractive aspects – either in terms of the veritable THWαMP variety or mere ‘attractive personalities’ – were deemed to be more intelligent, more courageous, and more (suitably) aggressive. Or, as Edward Lee Thorndike put it, a ‘halo effect’ (or ‘devil effect’ for less attractive recruits) was created in an instant, and this distorted people’s assumptions about their entire character and potential.

We might consider where the competency models fit into all this. Many competency models are configured on the basis of analysing the competencies of existing leaders. These are then distilled into a manageable list and recruitment methods are then moulded around the required competency frameworks. But note what this does: it takes an existing group of leaders and attributes their success on the basis of competencies that are allegedly important in generating the success. For those of you who smell a circular argument in here, you have found one. What we actually need to do is compare groups of successful and unsuccessful leaders, or leaders and followers, and then see what is different about the (successful) leaders and trace the causal connections to success. Otherwise, we don’t know whether what we have is correlations or causations. It may be, as we have already seen, that being a THWαMP is correlated with successful organizations, and it may well be that being a THWαMP is a prerequisite for successful organizations – but it may equally be that successful organizations simply recruit people who are THWαMPs. So unless we can be certain that the existing competency framework really is the cause of success (or failure), we should be very wary of going down this path.

This would not matter quite so much if we already had a very diverse leadership that reflected the population – it would simply mean that diverse organizations would keep reproducing their own bias and thus the diversity would persist – but not change. However, since organizations tend to be led by THWαMPs, we can look forward to getting more THWαMPs in the next generation of leaders. Is this just a case of selecting in your own image, or is there another reason?

If we consider the utility of social identity theory, we might get a glimpse of an alternative explanation. This approach suggests that we always tend to place other people in categories that are either favourable, because they support our own identity, or unfavourable, because they are deemed to be different from us. This identification process is both individually and group-oriented, so that under certain conditions we perceive individuals as representatives of groups, not as unique characters. Indeed, personal identity – the ‘I’–does not exist in isolation from social identity – the ‘we’. Once categorized the theory then suggests that we constitute differences within the in-group (us) as smaller than those between the in-group and the out-group (them). Furthermore, the in-group’s norms and stereotypes (which are largely favourable) lead to specific comparators to ensure self-enhancement. For example, young girls living on a run-down council estate are likely to view supermodels not as better than themselves but as unable to survive in such a tough environment -thus the comparator reproduces the self-enhancing social identity of the girls.

Furthermore, this whole process generates prototypes that emulate the social identity of the group and depersonalize its members, who appear so similar they become interchangeable: we expect to agree with each other on group-related issues, we tend to support emergent group norms, and we advance the interests of the group above our own personal interests. In effect, ‘we’ perceive ourselves as all alike in our positive attributions and perceive ‘them’ as essentially identical in our negative perceptions about them. This serves to reduce any uncertainty we have about ourselves, our status, our likely behaviour, and it does the same for ‘them’.

Such prototypes are seldom so clearly articulated that we would expect people to be able to write them down in an agreed list; indeed, they are likely to change in time and space as the context changes and to become more important as group membership becomes more important – often in response to an external threat. The consequence for leadership is that those group members who are closest to the group prototype are likely to have most influence – to become and remain the leaders as long as the conditions continue. Since this influence relates to the prototype, not the individual (though it appears otherwise to the group members), that implies that changing conditions generate different prototypes, and this explains why prototypical icons can suddenly seem to lose influence. For example, Churchill was regarded by many of the British as a belligerent and dangerous maverick in the 1930s, but as perfectly encapsulating the self-perceived prototypical character of the British under threat – a stoic bulldog in the face of great danger – hence his popularity and rise to pre-eminence as prime minister. However, once the war was over his character – which had not changed – was perceived to be out of kilter with the requirements of the post-war world. For that, the more congenial and inclusive character of Clement Attlee was the required prototypical leader.

Prototypicality, then, depends upon contextual stability, though as was suggested in Chapter 2, the framing and reframing of ‘situations’ is part of the armoury of any leader. Nonetheless, there are several techniques that leaders used to prolong their control which feed into the prototyping model:

• Accentuate the existing prototype – be more like one of ‘us’ than embody some ‘superior’ traits or appear like one of ‘them’.

• Seek out and attack in-group deviants – this is the point where dissent, constructive or otherwise, is reframed as the action of ‘traitors’.

• Demonize the out-group to deflect attention from internal problems.

• Stand up for the group – demonstrate favouritism to in-group members rather than fairness between groups.

The leader, therefore, is likely to be the in-group prototype:

• The person most representative of shared social identity.

• The person who exemplifies what in-group members have in common – maximum intra-group similarity; and exemplifies what makes them different from the comparative out-group -maximum inter-group difference.

• The person who makes ‘us’ feel different from – and better than – ‘them’.

The riots in Iran in June 2009 and in the Xinjiang province of China in July 2009 are good examples of how this approach makes sense of the decisions of leaders under duress. This also explains why ‘groupthink’ (the tendency for groups to suppress internal dissent) is prevalent amongst groups under pressure and why minorities and non-prototypical individuals and groups find it so difficult to break into leadership positions within established organizations and institutions.

That doesn’t mean it’s impossible, but it does mean it’s very difficult. In fact, when a crisis breaks out, the position of the prototype leader is usually strengthened. For example, Gordon Brown’s position as Prime Minister of the UK was under immense threat in the summer of 2008 as he struggled to demonstrate an alternative vision for the post-Blair Labour Party. But as soon as the financial crisis hit in the autumn of 2008, all thoughts of displacing him were dropped as the Party pulled together and it sought the protection of the person with the most prototypical character required in a financial crisis – the dour, responsible, serious face of the ex-Chancellor of the Exchequer: Gordon Brown. Yet ironically, nine months later, when the same British Prime Minister again faced significant rebellions as the expenses scandal broke within Parliament, he failed to act as the fiscal ‘witchfinder general’, and thus allowed the scapegoat hunt so common when uncertainty descends and we seek a resolution by concentrating blame upon the individual leader – Gordon Brown.

But success for prototypical leaders depends not just on persuading ‘us’ that we are different from and better than ‘them’, but also on persuading ‘me’ and ‘you’ to become ‘us’. Luckily for leaders, that need not be that difficult because it depends not upon rational analysis of ‘the facts’ but upon an emotional and often unconscious response. In fact, all that is required is Benedict Anderson’s ‘leap of imagination’. What he meant by that was that since we could never really know whether other people were really like ‘us’, or like ‘them’, we simply had to imagine one or other was the case. Thus, it did not matter that the soldiers on both sides of the trenches in the First World War actually had more in common with each other than with their respective leaders in terms of quality of life, income, habits, and so on. What mattered was that ‘they’ were obviously very different from ‘us’, and that turned ‘you’ and ‘me’ sufficiently into ‘us’ to want to fight ‘them’.

We can see this in action in the construction of British and French identity, for there are good grounds to suggest that until the war between the revolutionary French army under Napoleon and the British, under Wellington, it may be that most people in Britain regarded themselves as English or Scottish or Welsh or Irish – but not British. Similarly, the ‘French’ might have considered themselves to be Breton or Norman or whatever region they came from – but not French (indeed, most people in France at the time did not speak French but a regional language). However, the war catapulted the two nations against each other, and the collision propelled Napoleon and Wellington to leadership positions not just as generals but as prototypes for their own ‘new’ nations. Thus, we can read the literature at the time as pitting two prototype leaders against each other who are representative of their own nation. Napoleon and Wellington are not perceived as two individuals doing similar jobs, but as two encapsulations of diametrically opposed nationalities – which are formed in the crucible of war. The lists of character words below represent how these two individuals and countries came to be identified with one side against the other.

Let us return to the beginning of this chapter to conclude. We began by looking at Warren Harding as a popular but ineffective leader and the role of first impressions that generate halos which bias our interpretation of leaders. That implies that we need to be very careful about the issues of micro-leadership. By that, I mean we perhaps put too much emphasis on the rational aspects of leadership – the vision, the policies, the experience that leaders bring – and not enough emphasis on the emotional aspects of leading – the way people interpret very small acts, sayings, glances, body language, and so on. Of course, there is a whole raft of writing on emotional intelligence – and there are many different definitions of the term – but we should be aware that people with high emotional intelligence are not morally superior to those without high emotional intelligence. Hitler, for example, was extraordinarily effective in manipulating people’s emotions, but this does not make him objectively moral. Moreover, it is because emotions are such a powerful motivator that we ought to limit their significance – that, after all, is the reason for living according to a system of laws rather than at the whim of a tyrant whose emotional intelligence is a liability for all who disagree with the tyrant. Nevertheless, we are more enamoured of leaders who remember our names and who feel like one of us than of leaders who never deign to say hello to us but have astute policies for dealing with a world so complex we don’t even pretend to understand it or them. Indeed, they are not like ‘us’ at all; they are more like ‘them’.