Gallipoli remains one of the most discussed campaigns of the Great War. Fought against the Ottoman Turks on their homeland over a period of just eight months from April to December 1915, the campaign was costly, with casualty rates of around 250,000 for each side.

The Allies had intended to knock the Ottomans out of the war, quickly and efficiently, by using the naval might of Britain and France in ‘forcing the Dardanelles’. But this aim soon dissipated as the naval assault faltered and battle moved onto land. After the landings on 25 April 1915, the Allied forces were committed to a hard fight in which the Ottomans held the advantage. For most of the campaign, the Allies, under the command of General Sir Ian Hamilton – Britain’s most experienced general not yet given a command – were left to slog it out under trying conditions, desperately seeking to break out from the small, hard-won, beachheads.

From its inception, Hamilton’s force had been undermanned. And as his relationship with the British Secretary of State for War, Lord Kitchener, had been less than assertive, the supply of fresh troops to the peninsula fell foul of the pressing need for more men on the Western Front. Gallipoli remained a ‘sideshow’, and a costly one, but recognising how damaging a withdrawal might be to British prestige, in June the British Government’s Dardanelles Committee finally committed to send fresh divisions to the peninsula.

They would not arrive before August, however, and in the meantime, despite fresh attacks in June and July, the campaign stagnated and the Allied troops were still left grimly holding on to much the same tiny parcels of land they had wrested from the determined grasp of the Ottoman Turks.

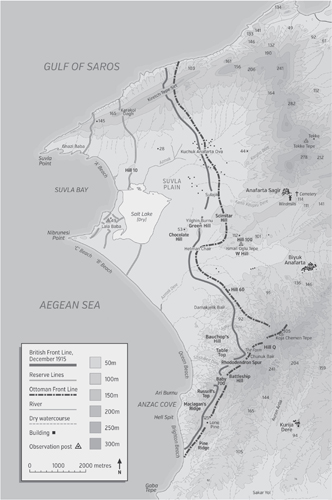

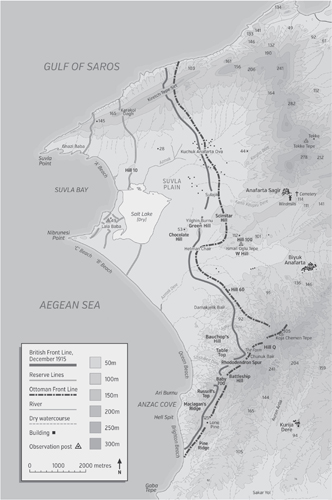

Buoyed by the promise of new troops, General Sir Ian Hamilton renewed his efforts to carry the Ottoman-held high ground and continue on to the original objectives – the capture of the coastal defences that had barred the navy from passing through in March. Taking the lead from Lieutenant General Birdwood, the Anzac commander, Hamilton proposed that the poorly held heights of Chunuk Bair – a dominating position in the Anzac Sector – should be taken in reverse. This would mean the deployment of Anzac, British and Indian troops in the complex of arid ridges and incised nullahs (dried up watercourses) to the north of Anzac Cove.

On 7 August, two columns would stealthily work their way up steep valleys in an attempt to get to the top of Chunuk Bair and sweep away the Ottoman defenders. Keeping the Ottomans occupied meant that the men of Anzac and Helles would once again be called to fight frontal battles against strong defensive works. There were fierce diversionary attacks by the 29th Division at Helles, and by the 1st and 2nd Australian Brigades at the heavily fortified redoubt at Lone Pine. Both actions were intended to draw enemy troops into the maelstrom, and away from the heights – the true target of the Allied offensive.

Alongside ferocious fighting to take the heights of Sari Bair, there were also new landings, full of hope, at Suvla Bay. Hamilton had been promised four new divisions by the Dardanelles Committee to reinforce his command. Yet the Allied beachheads were crowded, with little space to manoeuvre. Reinforcing either Helles or Anzac with this many men would be difficult, and could see the fresh troops frittered away with little gain. Sending them either to the head of the peninsula at Bulair – with the hopes of isolating the Ottoman garrison – or to the Asiatic shore of Anatolia, were unrealistic.

Instead, the inviting but scrub-covered plain of Suvla Bay, backed by sandy beaches and adjacent to the Anzac Sector, was the target. Formed into the IX Corps were three New Army divisions, the 10th (Irish), 11th (Northern) and 13th (Western). Attached to the new corps were the 53rd (Welsh) and 54th (East Anglian) divisions. And prised from the grasp of General Sir John Maxwell’s command in Egypt, was the 2nd Mounted Division, comprising four brigades of yeomanry – men who would have to leave their horses behind, and fight on foot. An army corps of this size required a senior general to command it. With the most experienced commanders committed to the most significant front, in France and Flanders, the choice was limited. Constrained by Edwardian conceptions of seniority, only Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Stopford was available – a senior general, but one with no active experience of command.

Though Stopford was inexperienced, he was enthusiastic. As the landings at Suvla Bay were an adjunct to the main assault of Chunuk Bair, his responsibility for securing the bay and plain as a supply base was not seen as onerous. Instead it represented a means of supporting the Anzac Sector once the heights had been captured, with the possibility reopened for the Ottoman coastal defences to be compromised and the navy to press on, once more, for Constantinople.

Perhaps for this reason Stopford was happy to let the campaign run out of steam; certainly his inexperience led to confusion. And yet compared to the tortured landscape of Anzac and the low, incised slopes of Helles, Suvla was open, constrained to the north by a sharp coastal ridge, to the south by Sari Bair range of Anzac. To the east was a ridge that connected the villages of Anafarta to the foothills of Sari Bair:

For months the Anzac troops had looked across the Suvla Plain, surrounded on three sides by formidable hills, like an enormous amphitheatre, the salt lake glistening harshly, and the yellow aridity of the ground, which looks deceptively flat and uncomplicated, broken here and there by a few stunted olive trees. The feeling of desolation is almost tangible. There is hardly any shade, the glare from the Salt Lake assails the eyes, the ground is coarse and thirsty looking and the sentinel hills sweep in a great arc from north to south, grim, aloof and hostile, quivering in the heat.i

On 7 August 1915, while battle raged at Sari Bair, at Lone Pine, the Nek and Helles, the men of Stopford’s command landed on the beaches at Suvla. The general had already expressed some reservations about the possibilities of untried troops landing, getting ashore and pushing on some miles over difficult ground to take a complex of hills in the face of, potentially, a determined enemy. Keen to do the right thing, he was also unduly influenced by his bullish chief of staff, Brigadier General H.L. Reed VC. Reed had seen action in France, and knew that there, artillery was king and that to undertake offensive action against prepared positions without artillery support was tantamount to madness. There were to be no guns landed in the first wave, and Reed pressed his concerns home with his chief. Yet, at Suvla, while there were no guns, equally there were no Western Front type fortifications either – and the hills were there for the taking.

Hamilton’s orders to the IX Corps were simply to secure Suvla as a base: ‘Your primary objective will be to secure Suvla Bay as a base for all the forces operating in the northern zone.’111 Securing the base surely meant taking the surrounding hills, but Stopford faltered, his command fading. He tried to explain away his failure after the event, but in vague terms:

I much regret that the force under my command has not succeeded in gaining the high ground to the east of the bay, the importance of which I fully recognise ... it has been a great disappointment to me that an attack I had fully expected would have succeeded ... turned into a defensive action.112

His growing indecision filtered down his command and his fresh, but admittedly raw, troops were squandered and their advantage of surprise evaporated under inadequate command. The possibility to carry the peninsula was lost as the newly landed troops fought against mounting odds and the debilitating difficulties of the terrain.

Stopford’s resolve evaporated, as did the hopes of his commander-in-chief, who quickly disposed of the IX Corps commander and several of his subordinates. In the failed general’s place came Major General De Lisle, commander of the 29th Division, the most experienced troops on the peninsula – men who had been committed to the Helles front since 25 April 1915.

Arriving at Suvla on 15 August, De Lisle was horrified to see the inertia and confusion of the beaches, the poverty of command and control, and the inadequacy of the positions. His frank assessment was that the IX Corps was severely depleted, and that, day by day, the enemy facing it was growing stronger and better prepared to withhold an Allied attack. He therefore proposed that he would concentrate his action on the capture of that part of the Suvla hills that would secure the left flank of the Anzac Sector – Scimitar and W Hills – in combination with a joint Anzac, Indian and British attack led by General Godley at Hill 60, a low mound heavily defended by the Turks and threatening the security of the Anzac flank.

Slated for 21 August, the IX Corps attack would be bolstered by two brigades of the 29th Division brought from Helles, who would assault the sinuous ridge known as Scimitar Hill, and two brigades of the 11th Division, who would take the W Hills north of the Azmak Dere Valley. To the south a composite of New Army troops from the 13th Division, Gurkhas and Anzacs would assault Hill 60 under New Zealand command.

This was one of the largest battles of the Gallipoli Campaign, one of the most costly and, ultimately, its last offensive action. It was also this battle that would seal the fate of the commander-in-chief, Ian Hamilton, defining the enormity of the task of taking the peninsula. Much rested upon it, and into this battle the IX Corps Reserve, the 2nd Mounted Division – the Yeomen of England – were thrown, on the evening of 21 August 1915, marching across the dried out and terribly exposed salt lake of Suvla Bay directly into the throats of the enemy guns.

The topography of Suvla Bay is very different from that of the rest of the peninsula. Its spine is mountainous, created by numerous earthquakes that were as active then as they are today, and this defined the rocky difficulties of the Anzac Sector, as well as the long, rising slope of Cape Helles with Achi Baba (Alci Tepe) at its high point. But to the north of this rugged centre was the plain of Suvla, linked to the Aegean by the peculiarly arcuate bay, and to the coast of the Anzac Sector by its long curving beach. Henry Nevinson was a war correspondent in Gallipoli who could read the ground:

Inland, the plain naturally increases in area as the hills diverge towards the north-east. It is flat an open land, studded with low trees and bushes. Nearly all of the surface is waste, but small farms, surrounded by larger trees and patches of cultivation, occur here and there, as at Kazlar Chair ... and Hetman Chair about a mile north of it (‘Chair’ meaning meadow). The soil becomes more and more marshy as one proceeds, and in winter the region nearest the Salt Lake is waterlogged. The bush also grows more dense, but is crossed by sheep tracks, and is nowhere impenetrable.ii

Nevinson was aware of the importance of the surrounding hills, as well as the isolated hills that gradually coalesced with the high ground to the east that was to plague the Suvla operation. He observed what he described as a chain of hills in the bay:

The chain is now marked by a series of isolated knolls – first the low knolls around the [Nibrunesi] Point itself; then the broad-based rounded hill of Lala Baba, which rises to about 150 feet; then, beyond the southern end of the Salt Lake and a stretch of marsh and bushy plain, Yilghin Burnu (better known to us as ‘Chocolate Hill’, from its reddish-brown colour even before it was burnt), which is a similar but larger rounded hill, like an inverted bowl, rising about 160 feet; then beyond a brief but steepish dip or saddle, Hill 50 or ‘Green Hill’ (so called because the thick bush covering it was not burnt), rising to nearly equal height, but not so round or definite in shape; lastly, beyond a wide and distinctive break, the formidable mass of Ismail Oglu Tepe (known to us as ‘W Hill’ from the waving outline of its crest, but more officially called ‘Hill 112’ from its approximate height in metres.)iii

W Hill was a significant feature, commanding the spur of the plateau upon which the village of Biyuk Anafarta stands, and the approaches to the Sari Bair range – and the ever tantalising possibility of wresting the heights from the defenders. It was matched to the north by another significant, and easily identified feature, Scimitar Hill, east of both Chocolate and Green Hills:

Of almost equal importance in the campaign was a rounded hill which projects sharply from the Anafarta ridge of plateau north of Ismail Oglu Tepe [W Hill]. Down the western front of this hill, which looks over the plain to the very centre of the Salt Lake, and to Suvla Bay beyond, runs a broad yellow ‘blaze’ of bare ground ... This ‘blaze’ appears from the sea to be shaped like a Gurkha’s ‘kukri’ or an old fashioned Turkish Scimitar, and so the hill came to be called ‘Scimitar Hill’. But officially it was ‘Hill 70’ from its height in metres, and commonly the soldiers called it ‘Burnt Hill’.iv

To the south of these hills, across the dry valley of Azmak Dere, was another commanding feature, the spur of Damakjelik Bair and Kalajik Aghala (better known as Hill 60) beyond. Part of the foothills of the Sari Bair range, this spur blocked effective communication between Suvla Bay and the Anzac Sector and stood in the way of any chance of breaking the line by advancing up the broken topography of Sari Bair without having to take the strongly held opposing trenches of the Anzac Sector. The Battle at Lone Pine, on 6–7 August, had shown just what that would be like.

With the failure of the surprise flanking attack at Chunuk Bair, and the inertia of the Suvla landings, which served only to squander any chance there was to command the bay, Sir Ian Hamilton’s opportunities for action were severely limited. Hamilton had removed the generals who had wasted opportunities, and on 18 August, at Imbros, the commander-in-chief reviewed his options for future action. He knew that the exertions of early August had severely weakened his forces, and that there was very little left in the pot. But if he could just seize ‘a foothold on the high ground’ then it would be possible ‘to observe the drop of our shell’ and ‘knock out the landing places of the Turks’. Despite everything, Hamilton was still an optimist. If he could ‘get the enemy on the run’ he reasoned, ‘with the old 29th Division and the new, keen Yeomanry on their heels, we might yet go further than we expected’.113

In his Gallipoli Diary, a memoir published in 1920, General Sir Ian Hamilton set out what he thought the purpose of the attack was on 21 August 1915:

On the extreme right the Anzacs and Indian Brigade were to push out from Damakjelik Bair towards Hill 60. Next to them in the right centre the 11th Division was to push for the trenches at Hetman Chair. On the left centre the 29th Division were to storm the now heavily entrenched Hill 70 [Scimitar Hill]. Holding that and Ismail Oglu Tepe [W Hill] we could command the plateau between the two Anafartas; knock out the enemy’s guns and observation posts commanding Suvla Bay, and should easily be able thence to work ourselves into a position whence we will enfilade the rear of the Sari Bair Ridge and begin to get a strangle grip over the Turkish communications to the southwards.v

With limited objectives, it all seemed perfectly reasonable.

The 2nd Mounted Division was finally woken from its canal-holding duties on 11 August, when it was confirmed that they would be moving to the Dardanelles. For the Rough Riders, this was a second chance at landing on this fateful shore, for when they stood off the coast of Cape Helles in late April, they had sincerely expected to be sent ashore. Reorganised into two squadrons, ‘B’ and ‘D’, the City of London men left Suez on the 13th, and arrived at Alexandria the following morning, ready to board the transports for the Dardanelles. With their horses left behind, the yeomen had to hand in their leather bandoliers, belts and swords. In their place was issued the usual equipment of the infantryman. The webbing straps were unfamiliar to the territorial cavalrymen, and the pouches, containing 200 rounds of .303 ammunition, were bulky:

Infantry web equipment was served out to all ranks, and it took us some time to get accustomed to its intricacies, as not a single officer or NCO had seen anything except cavalry equipment before.vi

A mass of infantry equipment was dumped in the camp; everyone was paraded and fitted with unfamiliar implements, entrenching tools, and the like.vii

The sword drill the Rough Riders had practised was now obsolete. The yeomen would be expected to fight with the Short Magazine Lee–Enfield rifle and bayonet alone. Equipped as an infantryman, and dressed as an infantryman, wearing broad-brimmed Wolseley sun helmet and cotton khaki drill uniform, each member of the 4th London Brigade was ready to face action for the first time.

Most men boarded HMT Caledonia, while a small party joined the Knight Templar, men who were in charge of the transport. The prosaic language of the Regimental War Diaries of the brigade’s London regiments described the events:

1st County of London Yeomanry (Middlesex Hussars)

14 Aug 1915 ALEXANDRIA 9.45 am Commenced detraining at Alexandria and embarked on CALEDONIA. All carts and mules embarked on KNIGHT TEMPLAR. All transport animals were mules. Sailed in the afternoon.

1st City of London Yeomanry (Rough Riders)

14 Aug 1915 ALEXANDRIA DOCKS AT 6 am and embarked on board HMT CALADONIA [sic] 17 officers, 315 other ranks. Transport with 1 officer Lt E.T. PALMER and 36 other ranks embarked on HMT KNIGHT TEMPLAR sailed about 6 pm.viii

The Caledonia sailed without incident, though it might just have been a difficult crossing. That German U-boats were active in the region was underlined by the sinking of HMT Royal Edward close to the Greek islands on 13 August. Carrying replacement drafts for the ill-fated 29th Division, the Royal Edward was fortunate that the hospital ship Soudan was close by to pick up survivors; nevertheless, the losses were heavy. With so much shipping offshore from Gallipoli, it was feared that other troop ships could similarly be the target of German U-boats operating in the region.

Arriving at Mudros, the transport was crowded in with other ships into the tight confines of the natural harbour. Captain Wedgwood Benn of the 1st County of London Yeomanry, also on board the Caledonia, recorded his first impressions, boarding the ship on 13 August:

We embarked at once at Alexandria, in the Caledonia, a North Atlantic passenger ship equipped against cold rather than heat. The following day we were admitted through the boom into Lemnos harbour. Here at least we were at the ‘back of the front.’ Men were daily coming from and going to the war; there were hospital ships, things we had never before seen; and all around us was the parched and barren island of Mudros diapered with camps and military roads.ix

On board the Caledonia the Rough Riders and other yeomen awaited orders and received further inoculation – this time for cholera. There would be no time for recovery from any adverse reactions to the vaccine. Their final move to Gallipoli was to be made on the decks of the cruiser, HMS Doris, joining the other London yeomen of the 4th Brigade. Together ‘they had to remain on deck, tightly packed and with barely any room to sit’.114 At 11 p.m., the Doris pulled out of Mudros and set sail for Suvla. In darkness, the cruiser steamed through the night to anchor in the bay as dawn broke.

When the men had come ashore on 25 April, they had done so in open boats towed by lighters captained by midshipmen. The first troops to land on the hostile shore of Gallipoli had leapt out of the wooden-sided craft into the unknown. At Anzac, the men had beached at the cove that would bear their name forever, attempting to push up to take the very heights that men were still struggling to wrest from the grasp of the Ottoman defenders some four months later. But, in August the yeomen had the benefit of armoured craft, especially designed for such landings and the brainchild of the First Sea Lord, Lord Fisher. These ‘beetles’, so called due to their black colour and protruding booms, were the first real landing craft. Denied to the men on 25 April, due to wrangling within the Admiralty, they had been used for the first time on 6–7 August in the landings at Suvla. They would be used again to ferry the London yeomen ashore. The beauty of the scene that greeted them would not be lost on some:

Just before dawn on August 18th we arrived at Suvla ... a bay of exquisite beauty. Think of the most lovely part of the west coast of Scotland; make the sea perfectly calm, perfectly transparent and deep blue; imagine an ideal August day; and an invigorating breeze, and you can picture our impression of the coast of Gallipoli.x

The War Diaries of the London Yeomanry recorded this momentous day with a somewhat more matter-of-fact style:

1st County of London Yeomanry (Middlesex Hussars)

18 Aug 1915 SUVLA BAY 4 am Arrived SUVLA BAY and commenced landing at 6 am; bivouacked by 9 am. Camp under shellfire but no casualties, men commenced to dig themselves in. (There was a lack of entrenching tools owing to these being put on a different boat to troops)

1st City of London Yeomanry (Rough Riders)

18 Aug 1915 SUVLA BAY Landed at SUVLA BAY about 9.30 am, unmolested, shelled soon afterwards, no casualties.

3rd County of London Yeomanry (Sharp Shooters)

18 Aug 1915 SUVLA BAY Arrived in Suvla Bay T 5.30 AM – LANDED IN BARGES without opposition from the Turkish guns, but were shelled soon after getting ashore. Dug trenches on the NORTH side of the BAY. Artillery duel between the Turks and the Battleships in the BAY during the afternoon.xi

With the same desultory Ottoman shellfire evident that had caused such problems to the men of the IX Corps as they had landed at Suvla on 6–7 August, there was a recognisable need to move to shelter, if random losses were not to deplete the ranks of these fresh troops. From their arrival, the men gathered on the beach and were hurried inshore to the slopes of Karakol Dagh to the north of the bay, where they were instructed to dig in:

With the whole bay overlooked and subjected to spasmodic shelling – and indeed, the same could be said of the entire Suvla Front, save only for a few blind spots which were already much over crowded in consequence – dug outs were everywhere necessary, and for want of roofing and revetting material consisted simply of open pits with the loose earth banked around.xii

Safely bivouacked in dugouts, the regiment awaited developments. Shellfire was constant:

The shelling was new to us. It went on more or less continuously, and we soon learned to distinguish ‘Whistling Rufus’, ‘Asiatic Annie’ (at Chanak) and the rifle and machine gun fire. All day long the battle proceeds – a fine panorama from our villa. Shells seeking the transports, bursts of shrapnel over the hidden Salt Lake, and ‘whistlers’ aimed at the hidden horse dugouts ... Everyone was affected in much the same way by the shells. When we had our earliest close experience of them, I think we all felt a sinking and listened very anxiously when the whistling came too near. But the depression, once the shell had exploded, was followed by a sharp rise in spirits, showing itself immediately in a desire for sheer bravado and continuously in an exhilaration when the guns were not shooting.xiii

At the sight of the yeomanry, Ian Hamilton was buoyed with hope: ‘No end of Yeomen on the beaches: the cream of agricultural England.’115 Despite their confidence, they were unused to their infantry role. With the exigencies of trench warfare, it was necessary to pass on the rudiments to officers and NCOs at least. The value of extemporised ‘jam tin’ bombs – made from tins, gun cotton, ballast and fuses – were introduced to the yeomen just a day before they needed it. And on that day, 20 August 1915, at 8 p.m., the majority of the regiment moved across the sandy beach to the protection of Lala Baba, a small knoll on the southern headland of Suvla Bay, near Nibrunesi Point. Captain O. Teichman, Medical Officer of the Worcestershire Yeomanry, surveyed the scene on the 18th:

Looking across the Bay to the southern side, one could see the hill called Lala Baba to Point Niebruniessi [sic], and behind this spur could be seen numbers of our troops and guns encamped. To the south-east of our position could be seen the white coloured Salt Lake and Chocolate Hill (Yilgin Burnu) in the distance.xiv

The march was slow going. The Middlesex Hussars led off the brigade:

Infinitely slowly we struggled along a road bearing around the beach to the bluff or cliff called Lala Baba, the point closest to Chocolate Hill. Very different this from our last parade ... No laughing, no talking, all awed and silent marching in a never-ending file. When we halted we lay flat for sheer rest’s sake, so unused were we to the packs ... The ground at Lala Baba hid us from the guns on the Anafarta Hills, and we were thoroughly tired out when we arrived, we scarcely scratched up a protection on our allotted pitch before we sank down to rest for the night.xv

The Rough Riders followed on. And using their personal entrenching tools, and amongst the mass of yeomen, the Talley brothers scraped some shallow protection from shellfire and the elements.

Suddenly thrust into the front, and moved away from the order of military camps in the rear areas, the flow of correspondence from the two brothers slowed. Notepaper, once plentiful in the bazaars of Suez, was now limited, a precious commodity. All too often the inadequacies of the Field Service Postcard had to stand in for the words the two men wished to share with their beloved parents. Percy Talley took up the story from 20 August:

20 August 1915

Letter from the firing line

Gallipoli

My darling Parents

I expect you will wonder why you have not received any letters. I expect you will guess, I think I can tell you we are in the firing line, you will know whereabouts. We must not tell anything, some fellows I can hear discussing if it is worth while writing, well this is just to tell you we are both fit. If I cannot write you more than this shall send the printed cards. With oceans of love to all.

Ever your loving son

Per

Am writing this in my dugout while the enemy keep on firing.

Have met K. Stoecker,116 Owen Minshull and others that I know.

Percy prepared for the day’s action by writing home; his brother Frank, short of writing paper but well aware of the need to keep his family informed that he was fit and well, prepared to send off a Field Service Postcard, a standard card that served only to let the recipients know that their soldier was well. Often referred to in the language of the day as ‘whizz bangs’, usually a nickname for a high velocity shell, but also applied to this peculiarly barren type of correspondence, a note easily dashed off before action. Frank’s would be the last communication he would send home for some time:

Nothing is to be written on this side except the date and signature of the sender. Sentences not required may be erased. If anything else is added the post card will be destroyed.

I am quite well.

I have been admitted into hospital

Sick |

and am going on well. |

Wounded |

and hope to be discharged soon. |

I am being sent down to the base. |

|

letter dated |

|

I have received your |

telegram “ |

parcel “ |

|

Letter follows at first opportunity.

I have received no letter from you

lately.

for a long time.

Signature only Frank

Date 20-8-15

The date 21 August was a momentous one for the yeomen, their day of destiny.

The attack began at 3 pm, following half an hour’s continuous bombardment. The barrage was the best that could be mustered, but was nevertheless desultory, with little hope of seeking out the enemy’s gun positions situated in the heights. With high trajectory howitzers being the only guns capable of destroying the enemy positions, and with the British guns being few in number and worn from action, the Ottoman batteries continued to fire. Naval gunfire from HMS Swiftsure added to the tumult, but its armour-piercing shells were ill suited to this type of work. Nevertheless, the war correspondent Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett was impressed with the work of the guns:

Suddenly, at 2.45 pm. Every gun on land and sea, that could be brought to bear, opened up simultaneously. It was the greatest concentration of artillery fire yet seen on the Peninsula. From Chocolate Hill the scene was majestic. The enemy’s positions along a mile of front seemed suddenly to go up in one vast cloud of smoke and flame, and the country behind the Anafarta Hills disappeared from view. All I could see were flames and smoke, in the midst of which trees, scrub, and huge chunks of earth were hurled into the air. It seemed as if nothing could survive such an awful pounding from so many heavy guns.xvi

General De Lisle’s orders were for the 11th Division to capture W Hill – after having captured the Ottoman advanced trench at the area of cultivation known as Hetman Chair – while the veteran 29th Division would assault Scimitar Hill and Hill 112, the tip of the Anafarta Spur behind it. At the same time, in the Anzac Sector south of the watercourse of Azmak Dere, a composite force of British, Australian, New Zealand and Gurkha troops was to attack Hill 60 (Kalajik Aghala). Writing in 1928, the controversial correspondent Ashmead-Bartlett recalled his doubts about the attack. There was to be:

A general attack along the whole line from Scimitar Hill to Ismail Oglu Tepe [W Hill], and from there against the Turkish trenches running across Biyuk Anafarta Valley [Azmak Dere] to Hill 60, which would be attacked by the Anzac Corps. The news filled me with consternation. To attempt further frontal attacks on Scimitar Hill and W Hill appeared to me sheer madness. The Turks had two divisions entrenched up to their necks, and if these positions could not be taken when they were held by a few battalions of gendarmes, what chance had we now?xvii

The poverty of the British artillery preparation soon told on the men of the 11th and 29th Divisions assaulting the strongly held hills and the open ground before them. The Ottoman forward trenches were largely untouched, and the advance trench at Hetman Chair and its long communication trench leading to W Hill was still strongly held; this would play heavily in the assault. The 11th Division attack was fiercely pressed but was met with withering fire from the Ottoman trench position at Hetman Chair. The assaulting units began to lose their way, and were repeatedly driven back by the strength of the Ottoman position. The 11th Division drive for W Hill was effectively over just two hours after its start.

To the north, the 29th Division fared little better. Close to Green Hill, the tinder dry scrubby ground was ablaze – a result of the preliminary bombardment. Here, as the assault began, men of the Royal Munster Fusiliers, attacking the Anafarta Spur, had just managed to get forward; but as more men piled to the front, the troublesome trench works at Hetman Chair once more took its toll. Casualties mounted from both the Munsters and the Lancashire Fusiliers who followed, both battalions of the 86th Brigade, 29th Division, which had lost heavily on the very first day of the landings at Cape Helles. The Ottoman front line was intact, and the wounded suffered terribly in the fires that still burned over this shell-swept landscape.

North of the 86th Brigade front, men of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers were to attack Scimitar Hill, backed up by other troops of the brigade as it unfolded. Tragically, this distinctive hill had once been in British hands, having been reached by men of the East Yorkshire Regiment on 8 August, but it had been given up in confusion, after the battalion was given orders to retire. Since that point it had been strongly entrenched and was a formidable objective for the Inniskillings to reach. Nevertheless, the dash of the Northern Irishmen was such that the foot of the hill was reached in the first minutes of the attack, and surging forward, they breasted the ridge top, only to be heavily enfiladed by the Turkish works on the Anafarta Spur. The casualties inflicted were appalling, and the attack was broken; the men of the Border Regiment made another attempt on the hill and were once more driven back. By 5 p.m. the attacks on the W and Scimitar Hills were effectively over.

At 3.30, while the forward brigades were making their assault and ‘the attention of the enemy was engaged by these attacks’,117 the IX Corps Reserve were to move across the open plain in order to support the objectives assigned to the 29th Division and push on as far as they could go. General Peyton, once commander of the 2nd Mounted Division, was now in charge of the Reserve, and had selected his beloved yeomen to carry the job through.

From Lala Baba, the yeomanry led off in order, under the temporary command of Brigadier General Paul Kenna VC, crossing the Salt Lake. Captain Owen Teichman was medical officer with the 1st Worcester Yeomanry:

At 3.10 p.m. our Division and part of the Tenth formed up behind Lala Baba, and then, crossing the ridge, commenced to descend to the Salt Lake Plain. We were in the following order: Second Brigade (Berks, Bucks and Dorset Yeomanry), Fourth Brigade (three London Yeomanry Regiments), First Brigade (Worcester, Warwick and Gloucester Yeomanry), Third Brigade (Derbyshire and two Notts Yeomanry Regiments), Fifth Brigade (Hertfordshire and Westminster Yeomanry).xviii

It was the crossing of the Salt Lake by the yeomen that was to impress. War correspondent H.W. Nevinson described its peculiar topography in the summer of 1915:

The Salt Lake measures about a mile and a half at its greatest length and breadth each way, forming a kind of square with irregular sides. Its surface in summer is thinly crusted with salt deposit upon caked and fissured mud, fairly sound for walking or riding, though in places the foot sinks above the ankle, and on the south side to the knees.xix

Bare, the salt crystals formed from the evaporation of the lake in the summer heat, the dry lake bed shone in the sunlight and shimmered in the heat. With the yeomen in reserve, and with an absence of cover in the open Suvla Plain, there was no choice but to make the newly arrived soldiers cross the plain in full view of their enemies holding the hills beyond:

After about half-an-hour’s progress we reached the enemy’s shrapnel, through which, of course, we were bound to pass if we were to attain Chocolate Hill. As each line of the division advanced into the beaten zone, the shells did their part, being timed to burst just ahead of our march. Casualties began, but our orders were strict, and forbade us to stop for anyone ... Suddenly I saw with horror my troop hit by a shell and eight men go down. The rest were splendid. They simply continued to advance in the proper formation at a walk, and waited the order, which did not come for another quarter-of-an-hour, before breaking into the double.xx

Starting the attack in the afternoon, the generals hoped that having crossed, the sun, now on its track to set in the west, would be shining in the eyes of the Ottoman defenders. Even these hopes would be dashed. Instead of the bright sun, there was a mysterious mist that mingled with smoke from bush fires to mask the Ottoman defenders, and make the objectives that much more difficult to make out. It was as if nature had conspired against them.

The yeomen would have to move from the cover of Lala Baba to Chocolate Hill, immediately due west of the objective, the slopes of Scimitar Hill beyond. The war correspondent, Henry Nevinson, observed the action first hand:

The Yeomanry Division was ordered to advance from the cover of Lala Baba, where it had remained in reserve, and to take up its position under the slighter cover of Chocolate Hill. In extended order the small brigades, each numbering about 350, advanced with the steadiness and regularity of parade across the bare and fully exposed level of the Salt Lake. Some of the enemy’s guns diverted their fire from Scimitar Hill and showered shrapnel over the steadily moving lines. But their regularity was exactly maintained, and owing to the accurate distance kept in the intervals the loss was small. Only too eager to reach the firing line, they forced their way through the reserves of the 11th Division around the slopes on the left side of Chocolate Hill, and plunged into the brigades at the centre of the lines, already so much confused.xxi

It was the crossing of the Salt Lake, in full sight of the Ottoman Turks, which stirred many observers to write in glowing terms. From his position at No 2 Outpost in the Anzac Sector, Aubrey Herbert, intelligence officer with the Anzacs, described ‘an unforgettable sight’:

The dismounted Yeomanry attacked the Turks across the salt lakes of Suvla. Shrapnel burst over them continuously; above their heads there was a sea of smoke. Away to the north by Chocolate Hill fires broke out on the plain. The Yeomanry never faltered. On they came through the haze of smoke in two formations, columns and extended. Sometimes they broke into a run, but they always came on. It is difficult to describe the feelings of pride and sorrow with which we watched this advance, in which so many of our friends and relations were playing a part.xxii

The commander-in-chief, General Sir Ian Hamilton, also detailed the episode in some of his most descriptive prose in his Final Despatch:

The advance of these English Yeomen was a sight calculated to send a thrill of pride through anyone with a drop of English blood in their veins. Such superb martial spectacles are rare in modern war. Ordinarily it would always be possible to bring up reserves under some sort of cover from shrapnel fire. Here, for a mile and a half, there was nothing to conceal a mouse, much less some of the most stalwart soldiers England has ever sent from her shores. Despite the critical events in other parts of the field, I could hardly take my glasses from the Yeomen; they moved like men on parade. Here and there a shell would take a toll of a cluster; there they lay; there was no straggling; the others moved steadily on; not a man was there who hung back or hurried.xxiii

John Hargrave, a witness to the battle as a member of the 32nd Field Ambulance RAMC, was scathing in his later assessment of the deployment of the yeomen after their crossing of the Salt Lake:

The Yeomanry reached Chocolate Hill, where a hurried and almost worthless briefing took place. One brigade was to advance on Scimitar Hill, now a sinister smouldering black lump. Three brigades were to advance on Hill 112, at the tip of the Anafarta Spur. One brigade was to be held in reserve. Without more ado, and without any idea of a co-ordinated attack, the Yeomen of England ‘stumbled blindly into battle’.xxiv

The briefing the officers received at Chocolate Hill was to the effect that: ‘there was a far more formidable task than had originally anticipated. The 29th Division had failed to reach its objectives, and the Yeomanry were to try where Regular troops had failed.’118

The situation was challenging indeed, and there was little knowledge of what was ahead. On the left, the 2nd (South Midland) Brigade was instructed to pass through the front-line trench and attack Scimitar Hill, while on the right, the 4th (London) Brigade – with the Rough Riders at its centre – and the 1st (South Midland) Brigade would pass by Green Hill and assault Hill 112. The two other yeomanry brigades would support the attack.

The War Diaries of the three London regiments of the 4th Brigade instructed to take Hill 112 tell the story using the barest of facts:

1/1st County of London Yeomanry (Middlesex Hussars)

21 Aug 1915 3 pm moved out with Division. The Middlesex Hussars were the leading Regiment of the Division to leave Lala Baba about 3.30 pm. We moved across on the right of the Brigade to Chocolate Hill in line of troop column. We first came under shrapnel fire at about 4.45 pm and reached Chocolate Hill at 5.15 pm. On reaching Chocolate Hill the regiment was ordered to attack round the right slope past Hill 50 [Green Hill] and if possible get a footing on Hill 112 [the tip of Anafarta Spur]. As we had not reconnoitred the ground and had no opportunity of seeing it, I ordered Capt Watson to lead my firing line consisting of two troops each of B and C Squadron, whilst I would support him with the other four troops. We found a trench running from the slopes of Hill 53 to Hill 50 and utilised this as far as possible, but found it full of Munsters and Lancashire wounded [of the 29th Division, 86th Brigade] who were crawling back that it was impossible to make any progress there, so I moved over to the slopes of Hill 50 the bush of which was then in flames. Pushing on we occupied a trench on the West slopes of Hill 105. One troop being pushed out in front and digging themselves in. I was ordered to wait here and get in touch with General W[iggin]’s Brigade [1st South Midland], who were to form on our left. A Squadron of the Warwick Yeo and Gloucester Yeo also both squadrons of the Rough Riders, they prolonged my left eventually joining with General W[iggin].xxv

1/1st City of London Yeomanry (Rough Riders)

21 Aug 1915 LALLA BABA [sic] Regiment ordered to advance with Division from LALLA BABA to CHOCOLATE HILL at 3 pm, being 2nd Regt in the advance under heavy shell fire, on arrival at CHOCOLATE HILL halted ¾ hour and called roll. Attacked position E of HILL 50 [Green Hill], which was held and improved. Casualties 7 killed 27 wounded 8 missing. Total 42.

1/3 County Of London Yeomanry (Sharp Shooters)

21 Aug 1915 LALA BABA The 2nd Mounted Division of which we formed part marched at 3.30 pm to support the attack on the Turkish position. Heavily shelled across the open to CHOCOLATE HILL, where we deployed in the attack (2½ miles). In the attack, which followed, the Regiment formed the Reserve (third) line of the Brigade which was the RIGHT hand Brigade of the Division, and when the advance was checked, took up a position facing the RIGHT flank to counteract any counter attack. Held this position until past midnight.

The attacks were doomed to fail from the start. The objectives, such as they were, had changed. The officers in charge had received the slightest of briefings, and had therefore little chance of passing on their instructions to the men under their command:

No one in the division had any idea of the situation in front, or what had befallen the 29th Division, or of where and when the Turks would first be encountered. Only a few senior officers, and none of the juniors, had ever seen the ground. The mist was growing thicker, scrub fires were raging, and pillars of smoke were blotting out the view. Streams of wounded were struggling back to cover. The din of battle was deafening; and daylight would only last another hour.xxvi

On the left of the attacking front, facing Scimitar Hill, the 2nd (South Midland) Brigade were to link with the Welshmen of the South Wales Borderers, remnants of the 29th Division (87th Brigade). At 6 p.m. the composite force struggled up the slopes of the hill, through the haze and smoke of the battlefield and managed to reach its crest – the second time that feat had been achieved that day. This achievement was soon negated, however. Commanding the top of Scimitar Hill was Hill 112 at the point of the Anafarta Spur. This strong Ottoman position remained intact, pouring enfilade fire into the British, fire that only slackened as dusk descended. In the darkness, the crest had to be given up, and the attackers once more formed a ragged line at the foothills, back where they began.

Hill 112 was the target of what remained of the 86th Brigade (29th Division). The Munsters and the Lancashire Fusiliers had already been in the thick of the action with severe losses; at 5.20 p.m., understanding that the yeomen would be pushed forward in three lines to take the hill, the 86th Brigade reserve, the 2nd Royal Fusiliers (RF), were told off to await their fellow Londoners to press forward the attack.

While their colleagues were struggling to the crest of Scimitar Hill, the fusiliers waited for the yeomen before attempting to press home their own attack. But the men of the Mounted Division failed to appear, and at 7.30 p.m., the RFs retired to Green Hill. The 4th Mounted Brigade (Rough Riders at their centre), together with the Midlanders of the 1st Brigade, had been held up. As darkness descended, they were still struggling to make headway to reach Green Hill, their progress impeded by the mass of wounded of the remnants of the 29th Division’s Munster and Lancashire fusiliers. To make things worse, detachments were scattered, and took heavy casualties as they strayed into the range of the still heavily defended strongpoint of Hetman Chair, which was being assaulted, to no avail, by the 3rd (Notts & Derby) Yeomanry Brigade. And with Hill 112 still firmly in Ottoman hands, the advanced position on Scimitar Hill was untenable, the enfilade fire all too apparent.

By 9 p.m. on 21 August the battle was effectively over; at midnight, General De Lisle ordered the action to be broken off. Major General W.R. Marshall, commanding the 29th Division, was instructed to resolve the confusion. He ordered retirement to the starting position at Chocolate Hill, the recall of the yeomanry to their starting position at Lala Baba, and for carrying parties to retrieve the wounded.

Across Azmak Dere, the assault at Hill 60 by the composite force of Anzac, British and Indian troops was also a failure, with heavy loss. The last stand at Gallipoli was a failure. The Talley brothers had entered this maelstrom; both were hit on the march. Their letters in the days after the battle tell of the experience of the average trooper, each doing his duty as a ‘Yeoman of England’. They had joined the Rough Riders, full of hope, in August 1914; a year into the training, their regiment was thrown against the strength of the Ottoman defences in the last battle of the Gallipoli Campaign:

So ended the action of Scimitar Hill – at once the most costly, in proportion to its size, and the least successful of any of the Gallipoli battles. Only on the extreme right had any ground been gained, and even that small gain was recaptured by the Turks on the morning of the 22nd. The losses of the IX Corps amounted to 5,300 killed, wounded and missing out of 14,300 men who had taken part in the attack. The British troops had fought with distinguished bravery, but their task had proven impractical.xxvii

Percy Talley was first to write home after the battle:

22 August 1915

My darling Parents

Just a line to tell you that I expect you will have heard, that Frank is wounded, shrapnel in the chest, but he was quite cheerful when I left him to continue our advance. It has been truly an awful affair - we had to advance under an appalling fire. I was hit twice on the right arm by shrapnel but continued on. After I left Frank our advance was still awful, and how I got through this is a miracle, we had to advance from trench to trench under a heavy fire. I am thankful Frank is out of it, as he is married. I think we have to go through the same again tonight. Do think of me. I thought of you all under this terrible fire but I mean to come through. Cannot write any more, expect you will hear from Frank soon.

With love

Percy

Note from censoring officer]

Frank is wounded - not seriously I think shrapnel - just about the collar bone - he came on with us, but when we got to the dressing station they kept him there. They both behaved splendidly.

R.J.B.T.

Frank was indeed wounded. The two brothers had struggled across the Salt Lake and had both been hit with shrapnel. Percy, hit in the arm, had managed to carry on. Frank, receiving a more serious wound to the chest was more debilitated. With the strict orders issued that soldiers were not to stop and aid others in the movement of the 2nd Mounted Division to the battlefront, Percy had to press on.

Neither brother would know what had happened to the other. For Frank, out of the fighting, would be the thoughts that his brother may not have come out of the continuing battle alive. For Percy, the hope that his wounded older brother would have survived his wound and blood loss as he lay in the open.

Frank would finally write home, to his wife May and his mother, some nine days after he was injured in battle. He wrote from the 3rd Australian General Hospital, which had only been set up on 8 August 1915 at Lemnos:

30 August 1915

Island of Lemnos

My dearest May

My last letter to you was dated Friday the 20th, I am sorry not to have written before, but have only just managed to borrow a couple of sheets of note paper. I could have sent one of the field service postcards but thought the news I want to tell you might have frightened you.

Now should you hear rumours that we have been in action, this time it is quite correct. After I had written you on the 20th we had orders late in the afternoon to be ready to move off at 7.30 p.m. which we were after about a 5 to 6 mile march we settled down for the night, and in the morning dug trenches for ourselves, which however were not needed.

About 3 o’clock our Colonel told us we were to be held in reserve and when the first party had taken a certain hill119

we were to go up and relieve them. While crossing a rather long open stretch of country120 we were very heavily shelled by the enemy. I was unfortunate enough to get hit just near the collarbone, and laid out for about 5 minutes though I never lost consciousness. So I picked myself, rifle and spade up, and made after the others to the butt of a small hill about 800 yards distant and under cover and managed to get there safely. Here I discovered that something had gone through my tunic and shirt, and there was a little blood, so was attended on the spot by the R.A.M.C. which happened to be near.

I have since been sent from pillar to post which did not improve my condition until last Friday when I was landed here, and am now under the care of the Australian R.A.M.C. and am getting very good treatment, the Doctors are splendid men the chief being, Sir Alex MacCormick121 one of Australia’s leading men.

As far as the wound goes there is absolutely nothing for you to worry about it is going on fine no bones or anything broken, simply a question of time.

Don’t send any parcels here as they don’t reach us in hospital but are taken and kept. Please excuse more but lack of paper forbids, but I am quite O.K. (honest Injun122) so please don’t worry.

Love to all, yours ever

Frank

30 August 1915

Island of Lemnos

My dear Mother

There is not much in the way of news to give you, and I should have written before but for lack of paper, and have only now succeeded in borrowing a couple of sheets.

After I sent you the Field Service Card on the 20th we had instruction to move off and the next day we received our baptism of fire. I can only speak for myself and say that I was early knocked out by a piece of shrapnel shell; however, the wound was not serious and I managed to pick myself up and go on another 500 yds or so and get under cover and get attention. Unfortunately I could not go on so had to stay behind and after being passed from one place to another, sleeping on the hard ground, I am safely lodged here, and on a spring bed, so you can guess I am quite comfortable.

The wound is going on fine and ever so much better, no bones or anything broken and except for a bit of stiffness, [I] feel A1. I am sorry not to be able to give you news of Percy, though I know he will have written should the chance permitted. The last I saw of him was after I was hit and had covered the 500 yards already mentioned. He was quite alright at that time so he gave me a hand, but they had to continue to advance while I was left behind.

Please don’t think of sending parcels or anything to me, as it is quite unlikely that it would reach me, I believe all parcels for wounded men are kept and distributed where needed.

Don’t worry about me as I am quite fine, and I feel sure Percy is too, he had all his bad luck beforehand, while I did not.

Love to all, yours ever

Frank

Official notification of Frank’s wounding would be slow in coming. On 15 September 1915, the War Office sent out Army Form B.104–81 to George Talley, his father. The tone of this official pro forma was matter-of-fact. Receipt of this letter, in its brown manila ‘WAR OFFICE. ON HIS MAJESTY’S SERVICE’ envelope, must have been dreaded. What if things had taken a turn for the worse?

SIR,

I regret to have to inform you that a report has this day been received from the War Office to the effect that (No.) 2365 (Rank) Pte. (Name) F.L. Talley (Regiment) CITY OF LON. YEO. was wounded in action at DARDANELLES on the 21st day of August 1915.

I am at the same time to express the sympathy and regret of the Army Council.

Any further information received in this officer as to his condition will be at once notified to you.

For Percy, still at Gallipoli, the ordeal would continue. The failure of the attack on Scimitar Hill and Hill 112 on the 21st meant that on the 22nd, the 2nd Mounted Division was withdrawn. North of the Azmak Dere, the battle was over. South of it, in the Anzac Sector, the composite force struggled to wrest the summit of Hill 60 out of the grasp of the Turks. That grasp was firm. The Ottomans held on to the high ground until the evacuation.

The War Diaries of the 4th (London) Brigade outline the story of the days following. Exhausted from the assault, in the early hours of 22 August the yeomen retreated to the relative safety of Lala Baba, once more crossing the Salt Lake where the Talley brothers had received their shrapnel wounds. It was quieter this time, and the blackness of the night had closed in. Captain Wedgwood Benn of the 1st County of London Yeomanry described the relief:

We marched back across the Salt Lake to our camp, smart sniping killing a few, but under no shell fire of any kind. We climbed the field to the place which we had started, the men lined up, orders were given to unload, ammunition was worked out the magazines and left lying where it dropped, and at dawn the whole brigade fell into their ‘bivvies’ and slept soundly where they lay.xxviii

The War Diaries of the three London Regiments of the 4th Brigade give further detail:

1/1st County of London Yeomanry (Middlesex Hussars).

22 Aug 1915 About 2.30 am on the 22nd Capt. Watson came back from my advanced troops and informed me that he was of the opinion that we might push on. I went back to the Brigadier who was in the trench 300 yards in rear and told him that I thought that by a night attack we might gain a footing on Hill 112, but that if we waited till the morning we should be decimated. While occupying the trench we were continuously under rifle fire. I sent out reconnoitring patrols to the front and to the troop I had sent out NE of us and I had two men searching in the bushes for snipers south of my position. About 1.45 am acting with orders, I sent out Lt Roller and two men to push forward and find out our best line of advance to Hill 112. About 2.15 am I received an order to retire my regiment to Lala Baba. I immediately sent out patrols and 2/Lt Benn, who was acting Adjutant, to inform the troops round me that we were ordered to retire and also to 100 men of the Border Regt who were occupying a Turkish communication trench on our right. I waited as long as possible for the return of Lt Roller and his patrol but was unable to wait for his rejoining us as I didn’t wish to march my regiment across the open in daylight from Chocolate Hill to Lala Baba. We started about 2.46 and reached Lala Baba as day was breaking at about 4.45.

1/1st City of London Yeomanry (Rough Riders).

22 Aug 1915 Orders received at 2.30 am to return to bivouac behind LALLA BABA [sic] arriving at 4.30 AM moved out again at 8 pm to HILL 50 and went into dug outs at 10.30 pm Lt R.A.B. TROWER and 4 men of the Regiment to Hospital Ship Sick.

1/3 County Of London Yeomanry (Sharp Shooters).

22 Aug 1915 (Sunday) CHOCOLATE HILL Ordered to retire on LALA BABA at 2.30 am which we reached at 4.15 am Waited there all day. Casualties yesterday Major LLEWELLYN and 2nd Lieut de PASS wounded and 40 NCOs and men killed, wounded and missing. Marched at 8 PM for Chocolate Hill and dug ourselves in.xxix

The rest at Lala Baba was short lived, however. As dusk fell, the yeomanry were once again instructed to make the march back to the advanced position at Chocolate Hill, where they took stock of the situation:

1/1st County of London Yeomanry (Middlesex Hussars).

23 Aug 1915 Advanced from Lala Baba to Chocolate Hill. Received the following Chocolate Hill 23 Aug 1915: ‘General Peyton wishes to convey to all ranks of the 2nd Mounted Division his high admiration of their bearing on the first occasion they took part in a general engagement. He watched with pride the steadiness of the movement from LALA BABA to CHOCOLATE HILL under heavy shrapnel fire and later the gallantry and determination displayed in the attack. He deplores the loss of our gallant comrades who fell and knows their memory will stimulate to maintain in the future the high reputation the Division has already obtained for itself. Brig. Gen. Kenna who commanded the Division has already conveyed to me his admiration of the conduct of all ranks throughout the day especially the 2nd Mtd Brigade in reaching Hill 70 in spite of heavy casualties and the loss of the Gallant Commander Lord Longford.’123 Sgd Peyton General.

1/1st City of London Yeomanry (Rough Riders)

23 Aug 1915 CHOCOLATE HILL Regiment in reserve behind CHOCOLATE HILL Major F.R.A.N. KNOLLYS124 wounded by shell and removed to hospital ship 2Lt G. KEKEWICH joined from SUVLA BAY.

1/3 County Of London Yeomanry (Sharp Shooters).

23 Aug 1915 CHOCOLATE HILL Shelled at intervals all day and sniped at night.

On their arrival, the yeomen of the 4th Mounted Brigade, Percy Talley amongst them, set to work improving their position as the IX Corps front moved from the offensive to the defensive. Decisions were yet to be made on what the next action would be, but in the meantime, with the Ottoman forces getting stronger by the day, it was necessary to improve the position:

Chocolate Hill at this period was covered with low bushes, and having been temporarily occupied from time to time in emergencies was in a dreadful condition of filth and disorder. However, the troops who were now sent to hold it soon made improvements. Bushes were cut down and the ground cleared, and rows and rows of trenches and dug-outs were constructed. There was a daily shelling, and as these shells had some over the top of the hill and the shrapnel fell on the reverse slope, the beaten zone was considerably extended, in fact it seemed as if the hill was being scraped. However, as the dug outs became better constructed and the men more used to the job the casualties grew less and less numerous.xxx

The Rough Riders soon adapted to their new, troglodytic life:

At Chocolate Hill everybody led ‘a rabbit like existence, venturing abroad only by night, but biding close to his hole by day and scuttling to it at the first note of alarm’. Blankets and some cloaks were sent up from the dump on pack mules, and much of the day was spent in sleep ... After dark, however, working parties and ration carriers left for the front line and the hill side was almost deserted.xxxi

Trench digging, ration parties and hard work under constant observation by enemy snipers was the lot of the yeomen. Percy Talley, still wondering about the fate of his brother since he left him on 21 August, was to take his turn in this navvies’ war.

24 August 1915

My darling Parents

I wrote you the other day and got my letters posted by my troop officer, which I hope you have received. I will repeat what I said there. Frank was wounded rather badly, but I am sure not seriously, of course he did not continue on. I had two wounds both in the right arm, the first one knocked me quite over and I hear many fellows went down with this shell. Soon after I got another, which bruised me very badly, but I continued on to the last. It was perfect hell, we had to advance about three miles under a most awful fire, words fail to describe it. It was in the first three miles that I and Frank got it. After about ½ an hour rest we continued, of course Frank was not here, we advanced from trench to trench under a deadly fire for about a mile, dropping down, and up again. Well, we achieved our aim and hear every one was pleased with our work. The regulars who watched us advance, said it was very fine for troops first time under fire, our coolness was as fine as the regulars.

I am about as clean as this piece of paper and have grown quite a beard. Shrapnel shells keep coming over us, the snipers are terrible, they paint themselves green when up in trees, or grey if they are on the ground. I was so tired as we advanced that I actually went to sleep when lying down behind a trench, with the bullets flying oh so close, in fact only just missing them, it is terrible to look back on. I should think Frank would be out of it for about 7 or 8 weeks, I am glad as he is married. I have no more note paper left so cannot write any more letters, but will send you the field service cards. We are in the hopes of a big post coming in; I have not had any from home for about two weeks. You are all continually in my thoughts, please think of me, how nice it will be to be home once more.

My best love to you my dear parents and all.

Ever your loving son Per

I am quite well

Field Service Postcard

24 August 1915

I am quite well.

Percy L. Talley

Field Service Postcard

30 August 1915

I am quite well.

I received your letter dated Aug 4 and 11th

Letter follows at first opportunity.

Percy L. Talley

In the last days of August, and into September, the Rough Riders occupied the trenches at Chocolate Hill. This would represent the advanced line of the British at Suvla Bay; there would be no further attempts to drive the Ottomans from their ridge tops. The Regimental War Diary records the daily activity of the men, digging trenches, improving dugouts. The routine was starting to tell on the yeomen, and the combination of hard physical work, monotony of food and poverty of the water supply was to take its toll:

Neither then nor at any time was there any shortage of food, largely because rations were indented for several days ahead and the daily decline in numbers afforded a surplus. Nor was there any real lack of variety, although the jam was always apricot, and the Maconochie ration proved too rich for stomachs after a spell of semi-liquid bully and desiccated vegetables ... As food was plentiful, so was water scarce, especially for the first few days, while the wells were being developed.xxxii

With water so scarce, there was little chance to wash, and the men grew beards and descended into a filthy state while in the front line. The constant buzz and drone of the flies, their numbers multiplying in the heat and fed by the dead, meant that food was contaminated, and the inability of the soldiers to have even the most basic of washes added to the inevitability of disease. The drain in manpower was continual and increasing. Daily the men were reporting sick and being sent down to the clearing station and thence on to the field ambulance.

Shelling contributed to the drain in manpower, as did the constant sniping from well-developed Ottoman posts in no-man’s-land. The work of the Ottoman snipers figure in almost all accounts written from the Gallipoli battlefront. War correspondent Sydney Moseley, writing in 1916, commented:

There has surely never been a campaign where the sniper has reaped such a harvest. Speak to any man who has taken part in the operations even for one brief hour, and he will dwell half admiringly, half wonderingly, upon the manner and means with which the enemy has potted at our men from the most unexpected places.xxxiii

The Rough Riders were getting wise to their attentions, however, as their War Diary recorded:

Shelling becoming more troublesome each day, but casualties not frequent owing to improvements in dugouts and better arrangements for drawing rations and water, etc. Casualties now usually occur only from the first shell of a series, and in parties out at night from snipers.xxxiv

On 1 September the number of effectives stood at nine officers and 232 other ranks; just under a week later this had fallen to seven officers and 204 other ranks. This drain would continue.

Percy Talley, suffering from abdominal pain and already wounded, was living on borrowed time in the trenches of Suvla Bay; his brother Frank was well on his way to being transferred back to England.

4 September 1915

My darling Parents

I hear this morning that the wounded are being sent to England, so no doubt by this time you have seen Frank, you might let me know how he is. For myself I am quite fit and so far have dodged the shells and bullets, although at times they come far too close for my liking.125 Would you send me some writing paper and envelopes, this is borrowed and it is also at a premium. Also some cigarettes and tobacco would be nice, if you send any only Gold Flake nothing expensive in case they get lost. It would be so nice to have a wash, my beard is coming on and is beginning to feel comfortable. The last I saw Karl Stoecker126 he was quite fit, but was being moved from me.

Most of our work here is done at night digging trenches, etc., which is not pleasant when bullets are all around you. A job I had with nine others, going out in front of the trenches and keeping a watch was not exactly comfortable, although it is surprising how used you get to it. No doubt our casualty list will soon be in the papers and you will see for yourself our losses. How is everybody at home? I think of you so much and wonder if you are unhappy about me, well don’t worry I am really quite well, please remember me to all kind friends. The money I asked you to send me has not turned up, not that I want it at the present, as there is nothing to buy127 so don’t worry about that.

Now with kind love to you all.

Ever your loving son

Per

Field Service Postcard

6 September 1915

I am quite well.

Letter follows at first opportunity.

I have received no letter from you lately.

Percy L. Talley

8 September 1915

Trenches, Gallipoli

My darling Sister

Your letter of the 12th Aug I have just received and right glad to have it this is the latest date from home, have also received one from May128 dated 18th please thank her for me. Have you heard anything of Frank? Please let me know if you can it is now 17 days since he was wounded and I have not had a word. I suppose the letter I wrote telling of our move must have worried you all, but you must not do so, as at the present moment of writing I am very fit, better than I have ever been since I left England. Life in the trenches is not over pleasant, shells are continually coming over and you have to duck down in your hole. You realise when a shell has just burst what a near one you have had, you say my word I was standing up a second or so ago just in the wake of a shell, it is all luck and up to the present I have had it.

At night time the snipers come out and you have to walk about head well down the whole time or else you are liable to stop one. My two shrapnel wounds in the arm have quite disappeared having no ill effect, I am thankful to say. Of course we have lost a number of fellows, which makes me think and feel so sad, but of course one cannot go through such a terrible ordeal without casualties. I do hope Mother and Father are keeping well, I do worry about them so, their last letter was from Matlock of course letters take such a long time to come but what can you do don’t let them worry about me I don’t intend to be bowled over by a Turk. Things, although slow, are going well with us here, and feel some things must soon end. I am my dear, so sorry I did not think of your birthday, will you please take the amount I told you in a letter some time back when you mentioned about going to Weston, please do, also give my best love to Mabel for the 10th, which I have also forgotten. It will be grand to be home, I shall have so many exciting things to tell you all.

I do hope we shall never have to go through such another awful time as we did that Saturday, I am not a coward, but one realises how terrible it all is, specially when you see your comrades going down. That is the one thing that upsets me. The flies in the trenches are worse than ever, suppose that cannot be helped with all the smells caused by the dead. Please remember me to all kind friends at Muswell Hill, I cannot write to more than my home, I don’t seem to be able to give my mind up to it, one gets very nervy at times being bombarded and having to sit tight all the time. I wrote Marguerite,129 and had a reply a week or so ago, they seem all well. I have also received papers dated 17th and 18th August. Well old dear I think I have told you all that I can, so will close, please give Mother and Father a kiss from me, and many for yourself and kind love to all and the members of the numerous families.

Ever your loving brother

Percy

The number of effectives with the Rough Riders was now eight officers and 214 other ranks, through sickness, wounding and debility. Snipers had been a thorn in the side of the Allied forces at Gallipoli, and perhaps nowhere more troublesome than in the scrub-covered Suvla Plain. The Ottoman sharpshooters were audacious and determined, often establishing posts in no-man’s-land – just 200–300 yards wide – to test the yeomanry front line:

We were somewhat troubled by an enterprising Turkish post which had been pushed out to a point unpleasantly near. It was by this post, known familiarly as ‘Percy’, that our digging party was so badly used. The Turks in the general trench from time to time sent grenades over and fired their Maxim gun, but ‘Percy’ ranked as the official opposition.xxxv

With Percy Talley in the advanced trenches at Chocolate Hill, he was forced daily to keep his head well down to avoid the attentions of his namesake, the Ottoman sniper. Any dips in the parapet, or gathering points – like latrines – would be targeted. The yeoman brother would have to be vigilant while engaged in extending and improving his position. The Rough Riders’ War Diary expresses the frustration of having to remove this nuisance once and for all:

Advance Trenches

10 Sept 1915 All men working constantly to improve parapets and continue saps.

----------06.30 One man killed behind dugouts by sniper’s chance shot.

----------11.30 Two men killed by enfilade shrapnel shell while working in trench. Sniping very troublesome from certain tree and dugout some way in front of Turkish trench.

----------17.30 Two men crawled out of sap head to locate snipers. One man shot and killed, the other returned with aid of covering party, brought in body.

11 Sept 1915 At work in trenches and saps continued. Quiet day except for the party of snipers, who have now got up sandbags round a bit of trench running up to their tree. One man wounded when lying out with listening guard to sapping party. The stretcher bearer with him also wounded when a mile in the rear of our trench near dressing station.

12 Sept 1915 Reconstructing traverses in all trenches and making additional ones. All men fire five rounds each during day, and attempt to drive out sniping party.

13 Sept 1915 One sap about finished and only worked at by day. Men being rested more. Not much shelling during day.

----------19.45 Tried to turn out sniping party with one machine gun (previously sighted) and two troops, five rounds rapid, but no apparent success. And sniping continued as usual after the enemy had made a lively reply to our fire.

14 Sept 1915 02.00 Alarm from Worcester Yeo on the left, and regiment stood to arms. Very little firing. Fired from sap head at sniper’s tree and dugout with rifle grenades. Sniping at night very persistent.xxxvi

Under constant fire from snipers, shelling and trench mortars, the Rough Riders continued with their work. It was back breaking, and the men were tired and fatigued from dysentery. Sleep was often impossible:

Three saps were being driven forward continuously under what was called the ‘two hours system’. Who originated this system is undiscoverable, but it meant that in every six hours a man spent two digging, two on watch and two off duty. But as fatigues had to be performed and meals prepared, and as everybody ‘stood to’ morning and evening, the corporal or trooper was lucky to get a full two hours sleep at a stretch ... So tired out did the men become that at night sentries were posted in pairs to keep each other awake.xxxvii

Amongst this, and knowing that it was impossible to say what he really felt, Percy Talley was finding it difficult to maintain a flow of correspondence home, having to rely on ‘whizz bangs’ and borrowed sheets of precious paper:

Field Service Postcard

13 September 1915

I am quite well.

Letter follows at first opportunity.

I have received no letter from you lately.

Percy L. Talley

Field Service Postcard

16 September 1915

I am quite well.

I have received your letter dated 18th and 19th August.

Letter follows at first opportunity.

Percy L Talley

21 September 1915

Trenches, Gallipoli

My darling Parents,

We have just had an issue of two envelopes each man and I have borrowed this note paper, so am able to write you a note at last. The last letter I received from home was Aug 18th. In it you say it is the first since coming home from your holidays. At present we are in reserve trenches, otherwise so called rest trenches,130 and well I can do with it too. When in the front trenches you get practically no rest at all, it is terrible, but I am keeping fairly fit in spite of it all.

I have not heard a word of Frank, of course I feel sure he is alright, as I saw the wound, a nasty gash but absolutely nothing to worry about, simply a case of waiting for new flesh to grow. My arm is quite right now. Of course I suppose you are all very troubled, naturally, but you must not worry if I could only receive a letter from some of you to say you are not worrying and are all well, how happy I should be. You are both continually in my mind night and day, but wait until I come home, and we will have another holiday together, cheer up for my sake I find it hard enough out here all alone.

Please remember me to all members and branches of the families, I simply cannot write to more than you as there is such a scarcity of paper, and no inclination. Of course we are continually under shell fire, sometimes it seems they have forgotten all about us, then I suppose they see a few walking about, then come the shells one after the other, a general stampede for your dugout, this is a very good test for your nerves, mine feel like going at times - then again I don’t care a hang, you say oh well if I get one, I get it, and so life goes on much the same every day.

I am very sorry to hear of your headaches I do hope you may soon get rid of them, do you think you could get away for a week or so rest with Father, go to a seaside place? I would be so delighted to stand expenses, to think that you and Father were accepting a short holiday from me, you could not draw mine from the bank but you could take my monthly cheques until the debt would be paid, please do this my dear parents. I do hope my letters do not take such a time to come as yours do to me. How I do wish I could pop in and see you all and have a chat, I feel quite sad when I know it is absolutely impossible, so suppose I must save everything up until I do eventually see you all.

I will try and explain a listening party’s duty. We had one when building a sap, a couple of men would have to crawl out at the sap head and move along for a distance perhaps of 5 yards or so, and listen and keep watch, of course you keep absolutely flat on the ground moving along like a snake. This is done at night time; I have done it at night and day thank goodness they stopped the latter, as it was so dangerous. I had two hours of it all alone one afternoon, truly terrible, they stopped it when a few got hurt. Sniping is not so bad, we used to do it from our trench, at least not exactly ours, but occupied by another troop which looked on to the Turkish sap and also in the direction of fire from Turkish snipers, so we used to go there in turns to shoot. I am keeping this letter open until tomorrow as we are expecting a mail in. I wrote Mr Podger last on the back of one of the paper wrappers,131 you might tell him it is very hard to write under the conditions out here and if he does not hear from me well it is simply that I have nothing to write on, or perhaps on the move we do not have much time to ourselves I often think of him and Mrs Meyer and Mr Smith, when you see them you can mention it to them if you will. The post has just arrived and not one letter from anyone, only papers dated Sept 2nd, so will close this now. With oceans of love to you all my dear ones.

Your loving son

Percy