Testing Racial Fear

As the race-class narrative project was first getting going, a coalition called Our Minnesota Future saw promise in our approach. This group—led by Faith in Minnesota and SEIU Healthcare Minnesota—wanted to try a door-to-door canvassing experiment as soon as possible. Under time pressure as they evaluated whether to adopt the race-class approach in the looming 2018 election cycle, confirming that it actually worked in real conversations was key. Our research would not be done in time, so they decided to move forward independently, drawing on our as-of-then untested hypotheses.

For their experiment, they worked from an actual Republican mailer already circulating for the 2018 governor’s race—a big postcard in red, white, and blue, with large font, a flag-draped photo, and typical dog whistle rhetoric about “sanctuary cities” and “criminal and illegal aliens.” Our Minnesota Future would use this as the Right’s message. Against this, they would test two possible Democratic responses: a standard progressive economic message that stayed silent on race, and also a race-class message.

Using these mailers, in January 2018 Our Minnesota Future canvassed eight hundred homes across Minnesota, divided evenly between white and nonwhite households. Demos Action, a race-class narrative project partner, helped with the door knocking and canvassing conversations. The idea of going house to snowy house in the middle of a Minnesota winter seemed foolhardy. As it turned out, though, the freezing conditions seemed to make residents more willing to open their doors to invite the canvassers in.

Standing in people’s foyers or invited into their living rooms, the canvassers started by showing people the Republican mailer. After giving them time to look over its dog whistle message, they asked people to react to the flyer on a five-point scale: strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, or strongly disagree. Among white respondents, those saying they agreed outnumbered those disagreeing by almost two to one—45 percent initially agreed or strongly agreed, while only 24 percent disagreed or strongly disagreed, with the remainder indicating they were neutral or agreed with some parts but not others.1

The canvassers then tried one or the other of the hypothetical Democratic flyers, either the colorblind or the race-class version. After giving folks a chance to digest the new message, the canvassers cut to the chase to ask, “If the election were held tomorrow, which candidate would you vote for?” The point was to figure out which Democratic message, a colorblind one or the race-class narrative, would perform better against an actual Republican dog whistle message.

So how did the two Democratic flyers compare in their ability to compete against the Republican dog whistle message? Among those who initially disagreed with the GOP mailer, it did not much matter which Democratic flyer they saw. Almost all said they would vote for the Democratic candidate, whichever they were offered. No surprise there, since these were folks initially turned off by the Republican flyer. To them, supporting any Democrat—whether colorblind or race-forward—was preferable to voting Republican.

The important differences came in terms of the reactions among whites who initially agreed with the dog whistle message. Recall that people could either “strongly agree” or simply “agree.” This mattered.

Just 7 percent among whites said they “strongly agreed” with the racial fear flyer. Within this group, more than a quarter said they would switch and vote for the colorblind populist Democrat. In contrast, only about one in ten said they would support the race-class Democrat. With this group, then, the colorblind version substantially outperformed the race-class message. Their reactions suggest this cohort reacted to the racial content of the competing messages—and that among those most strongly in agreement with a Republican message of racial fear, a Democratic message of racial solidarity did not work well.

But that’s not an argument against the race-class approach. Remember, just 7 percent of whites said they “strongly agree” with the racial fear message. The largest plurality of whites, almost four out of ten, instead took the more moderate position of saying they “agree” with the dog whistle mailer. One can imagine Matt and Tom in this group. So how did they react?

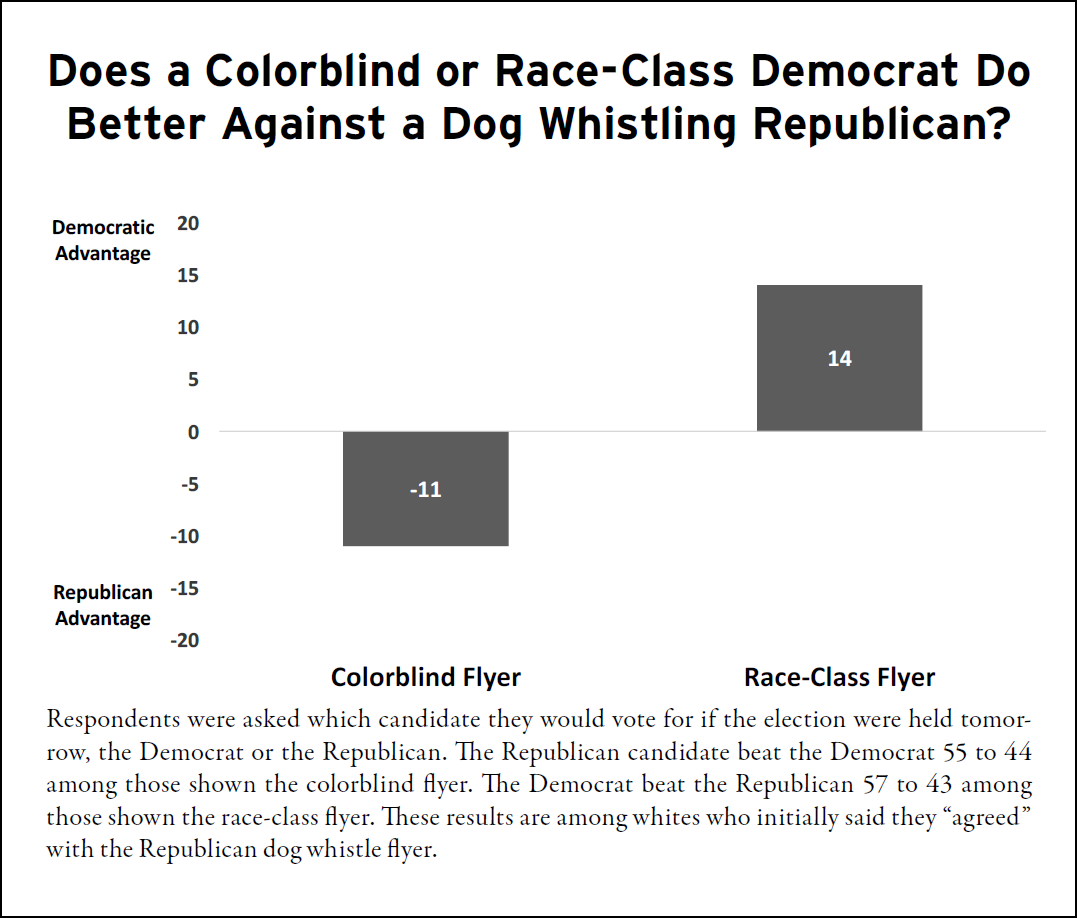

When shown the race-silent economic populist message, many switched from supporting the GOP candidate and said they would vote for the Democrat—but not a majority. The dog whistle candidate still received 55 percent of their support, compared to 44 percent who said they would vote colorblind blue. This was despite the fact that the economic populist message promised major reforms, for instance calling for fair wages and affordable healthcare for all.

In contrast, for those shown the race-class message, the numbers went positive. Now only 43 percent stayed with the Republican dog whistle candidate, compared to a winning 57 who favored the Democrat addressing both race and class.

Put differently, in a match-up with a Republican dog whistle message, a Democratic colorblind economic message lost, but a Democratic race-class message won. Moreover, there was a remarkable 25-point jump in net approval—from down by 11 to up by 14—when switching from the race-silent to the race-class script. Again, this was among white voters who initially said they agreed with the racially divisive message.

It’s important that the race-class message outperformed the colorblind approach that constitutes standard Democratic fare. It is also critical that it successfully counteracted the Republican racial fear message, something the colorblind approach failed to do. True, the Minnesota Republican flyer did not offer the same full-blown racial hysteria portrayed by Richard Corcoran’s “Kate Steinle” ad, but it used the same frame, warning about illegal aliens, criminals, and sanctuary cities. However demoralizing the success of such scaremongering messages in the Trump era, the Minnesota results—and the outcomes of the race-class project generally—show they can be beaten. Exploring how and why will occupy the bulk of this book.

At this stage of the book, however, the more important point is that progressives are up against coded appeals to racial fear, not clearly communicated and plainly heard endorsements of white solidarity. Look again at the visuals in the Minnesota flyers. The GOP mailer shows an American flag, whereas the race-class message features whites and Blacks shoulder to shoulder in camaraderie. If the white Minnesotans who initially agreed with the racial fear message were consciously committed to restoring white dominance, would they have switched their support to a candidate promising cross-racial solidarity? Would they turn and embrace a message that visually shows whites and Blacks with their arms around each other?

But they did switch, and not just a few, a majority of those who initially agreed with the dog whistle message. Yes, some whites are truly committed to restoring white dominance and, no, the race-class message will not sway them. But the Minnesota results strongly suggest—and research discussed later confirms—that the majority of whites who respond positively to stories of threatening nonwhites are not consciously committed to white superiority. On the contrary, though moved by narratives of racial threat, they also seem remarkably open to messages of economic populism tied to cross-racial solidarity.

Another aspect of the Minnesota research bears mention: the results among people of color. Strikingly, many respondents of color found merit in the dog whistle racial fear message. Compared to whites, fewer strongly agreed, but a roughly similar number said they “agreed” with the GOP flyer—35 percent among voters of color versus 38.5 percent among white voters.2 These results confirm that for many people, including many minorities, attacks on “sanctuary cities for criminal and illegal aliens” and other racial fear messages work at a subliminal level. The core narrative involves a story about threatening nonwhites and innocent whites. But once translated into coded dog whistle terms, acceptance of this narrative transcends racial boundaries.

It’s also important that, compared to whites, respondents of color were substantially more likely to switch to support the Democrat when given a chance. After being shown the race-silent Democratic message, people of color who initially agreed with the GOP message said they would vote for the Democrat by a positive margin of 15 points. They were even more enthusiastic when shown the race-class Democratic flyer. Given that choice, the positive Democratic margin increased to 34 points. It may run counter to the established wisdom that many people of color find dog whistle themes convincing. But even so, it remains true that voters of color respond very well to Democratic messages. The Minnesota results confirm the point made by many, for instance Democracy in Color founder Steve Phillips: there are big payoffs to reaching out to voters of color (including those who otherwise sympathize with some dog whistle messages).3

Testing the Right’s Dog Whistle Racial Fear Message

The race-class narrative project aimed to show that race-class messages could compete against dog whistle rhetoric. The best way to test this was through direct comparison in the same survey instrument. This, in turn, required that the race-class project craft a version of the dog whistle narrative. We combed through campaign speeches and political ads in an effort to closely mimic the actual messages bombarding people daily.

Here is what we concocted. It combined veiled warnings about threatening nonwhites with reassurances that racial fear is just common sense, echoing the way Trump implicitly assailed people of color but reassured his base.

Dog Whistle Racial Fear

Our leaders must prioritize keeping us safe and ensuring that hardworking Americans have the freedom to prosper. Taking a second look at people coming from terrorist countries who wish us harm or at people from places overrun with drugs and criminal gangs is just common sense. And so is curbing illegal immigration, so our communities are no longer flooded with people who refuse to follow our laws. We need to make sure we take care of our own people first, especially the people who politicians have cast aside for too long to cater to whatever special interest groups line their pockets, yell the loudest, or riot in the street.

How did the dog whistle message perform? Depressingly well. In national polling, we asked people to evaluate whether they found the statement convincing on a scale from 0 to 100, with 0 meaning not convincing at all and 100 meaning very convincing.* Republicans generally loved this statement. Almost three-quarters found it convincing, compared to roughly half of Democrats. There was also a sharp difference in the intensity of conviction. Almost one-quarter of Republicans rated this statement a perfect 100, for very convincing. In comparison, only 13 percent of Democrats gave it this highest possible score. It is good news that Democrats liked this statement less—but bad news that even among Democrats, it still received a generally positive rating. Indeed, less than one in three Democrats, 31 percent, rated it in the unconvincing range below 50.

What about the racial breakdown in how people reacted to the racial fear message? It stands to reason that people of color would overwhelmingly repudiate a message that describes them as threats to society. But as in the Minnesota canvassing experiment, that did not happen. Instead, there was a shared agreement across racial groups that this message was convincing. Among whites, roughly three in five found this message convincing—as did a similar number of Latinxs. African Americans were only slightly less convinced, with more than half rating it convincing. Indeed, there was more divergence in reactions to the racial fear message between Democrats and Republicans than between whites and Blacks.

The racial fear message was widely popular. Here are two important implications. First, the Right’s message has real traction with a broad swath of American voters. The term “common sense” in the message, and in Trump’s mouth, captures how a dog whistle narrative of racial fear comes across as reasonable and convincing to very large numbers. Second, when majorities of Democrats, African Americans, and Latinxs find the racial fear message convincing, this is coded, not naked, racism.

Why does this message have broad traction across parties and racial groups? It’s more than simple repetition, as powerful as that is. Rather, the racial fear message connects to a deeper story from the Right linking race, class, and government. Let’s turn to examine that core narrative.

* The March 2018 national survey reached 1,500 adults, plus oversamples of 100 African Americans, 100 Latinxs, 100 millennials, 100 persons who had voted in 2012 but not in 2016, and 100 persons eligible but unlikely to vote. We weighted the data slightly by age, region, race, gender, and education to reflect the attributes of the actual population. The margin of error for the total sample was +/− 2.5%.