How the Right’s Core Narrative Shapes the Political Landscape: Base, Persuadables, and Opposition

Ideas about race, class, and government have been intertwined in the United States since the country’s founding, and the Right continues to powerfully link them today. To gain a sense of the contemporary political landscape, the race-class project asked a series of survey questions designed to probe people’s views on these three elements. Exploring the fundamental Left-Right divide regarding the root cause of economic hardship, we asked, for instance, if poverty stemmed from individual faults or instead resulted from structural factors. Exploring how this applied to people of color, we asked if minorities who cannot get ahead are mostly responsible for their own condition. We also asked whether government has a positive role to play in solving problems or instead should get out of the way.

Close to one in four respondents, 23 percent, gave consistently progressive answers, blaming structures more than personal dysfunction and endorsing government’s power to help. These people were slightly more likely than the general population to be women, Democrats, African Americans, and/or Latinxs. Even so, white voters comprised more than half of this cohort. Together these voters form a solid progressive base. Energizing them is the first critical step to coalition building.

Standing opposite the progressive base were committed reactionary voters. They numbered almost one-in-five in the national sample, 18 percent, and adopted reactionary positions down the line, blaming individuals and disparaging government. Overwhelmingly comprised of whites and those who identified as Republican, this group is as terminally red as a stop sign. They will not join a progressive coalition, and shaping progressive messages and policies to win their support is a fool’s errand.

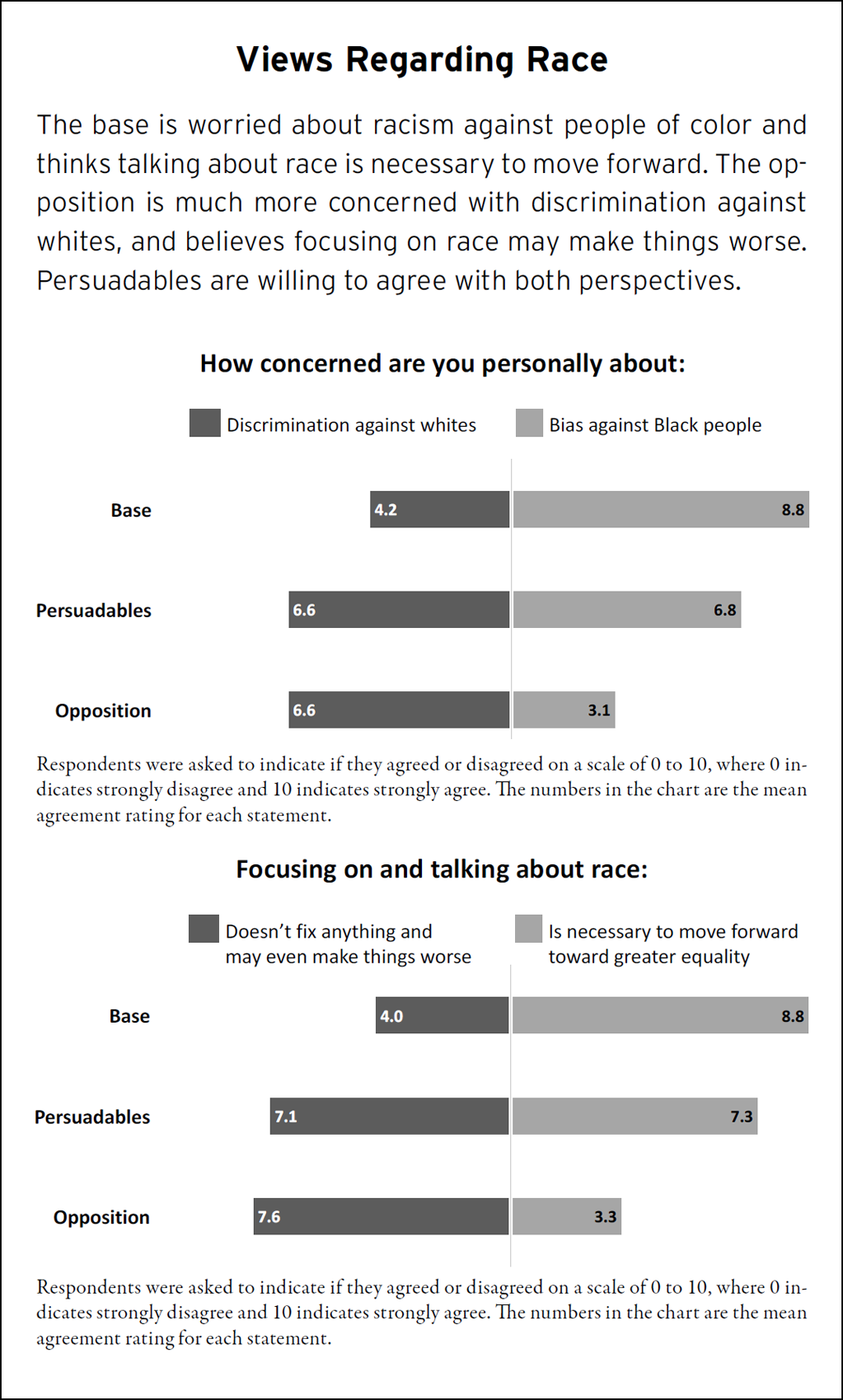

Between the base of committed progressives and the opposition of fixed reactionaries live the vast majority of voters in this country. Almost three in five in our national survey, 59 percent, embraced both reactionary positions and progressive visions of society. For instance, when we asked whether “talking about race doesn’t fix anything and may even make things worse,” a super-majority of those in the middle agreed. But when we asked instead if “focusing on and talking about race is necessary to move forward toward greater equality,” almost the same number said yes to that, too. Using a different method, the Pew Research Center came to roughly similar conclusions. They found that about seven out of ten voters hold beliefs that mix liberal and conservative commitments.1 In contrast to the “base” and the “opposition,” we called this cohort that could go one way or the other the “persuadables.” Encompassing so many Americans, this group roughly tracks the demographics of the country generally; it includes people of color, white working-class voters, Democrats, Republicans, and some Trump supporters.

The next three boxes bring into view the conflicting perspectives held by the base and opposition regarding race, government, and the marketplace. They also illustrate how the persuadables typically hold both sets of beliefs, making this election-determining group susceptible to being pulled in either direction. A fourth box shows that the base-opposition split largely tracks an inclination to vote Democratic or Republican, while the persuadables straddle both parties.

Which Group Sits at the Heart of the Opposition?

Stephanie McCrummen is a Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist for the Washington Post who hails originally from Birmingham, Alabama. Like many other reporters after Trump’s election, she sought to understand who elected him and why. To do so, McCrummen traveled back to her home state, to the small town of Luverne.

“I hate it,” said Terry Drew, a congregant in the First Baptist Church. He was explaining to McCrummen the blatant moral compromise of voting for an immoral man like Trump. “My wife and I talk about it all the time. We rationalize the immoral things away. We don’t like it, but we look at the alternative, and think it could be worse than this.” What would be worse? High on the list was the possibility of a president who supported abortion rights.

Sheila Butler, another church member, also worried about “the annihilation of Christians.” “Obama,” Sheila said, “he carried a Koran and it was not for literary purposes. If you look at it, the number of Christians is decreasing, the number of Muslims has grown. We allowed them to come in.”

“Obama woke a sleeping nation,” her friend Linda added. Sheila corrected her: “He woke a sleeping Christian nation.”

Sheila was certain the Bible’s moral commands regarding how to treat others meant how to treat other Americans. Love thy neighbor, she said, meant “love thy American neighbor.” Welcome the stranger? That meant the “legal immigrant stranger.” “The Bible says, ‘If you do this to the least of these, you do it to me,’” Sheila explained, “but the least of these are Americans, not the ones crossing the border.”2

McCrummen had hit pay dirt.

In 2016, white evangelical Christians comprised one of every five voters in the country. They also came out for Trump by a margin of almost five to one. With their high numbers and impassioned fervor, white evangelicals alone accounted for one-third of all Trump’s votes.3 In other words, if there is a single group that put Trump into the White House, it’s white evangelical Christians.

One reactionary evangelist put the point in more biblical terms. “If you back the evangelicals out of the white vote, Donald Trump loses whites,” Ralph Reed told the crowd at the Values Voters Summit in 2018. “If the rapture had occurred, Donald Trump would have lost by the worst landslide since George McGovern.”4

It’s worth keeping in mind that 16 percent of white evangelicals voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016.5 Also, in the first years of the Trump administration some anecdotal evidence emerged that a few white evangelical women might be turning away from the Republican Party.6 In addition, long-term trends show that white evangelical Christians are declining in numbers and influence decade by decade—though this very decline may also lead to further radicalization.7 Finally, on an interpersonal level, many are good people. They are not deplorables. Indeed, speaking personally, I’m fortunate to count some white evangelical Christians as wonderful neighbors and friends.

But these facts don’t change the basic math. White evangelical Christian voters represent the perfect storm fueling the Right’s electoral strategy.

Start with race and gender.

The roots of racial resentment among white evangelical Christians go down past the general racial grievances that trouble many whites. A strong taproot extends back to the fight against school integration. In the 1960s, initially in the South and then spreading across the country, many whites fled public schools to avoid racial integration. When they did, they often retreated to private academies associated with their churches. As these institutions came under criticism, defending segregation morphed into defending Christian schools and then more generally into defending Christianity.8

Likewise, the endorsement of patriarchy among white evangelical Christians also has especially deep political roots. In the early 1970s, evangelical churches as well as conservative Catholics led the countermobilization against feminism. To woo these groups, Republicans proclaimed a “pro-family” identity centered on supporting traditional gender roles for women, opposing abortion, and condemning homosexuality. As one critic observes, “For the Republican Party, long seen as the party of big business rather than labor, embracing the pro-family movement’s positions enabled it to claim to be the champion of the family without championing programs designed to protect jobs or wages.”9

In 2015, PRRI asked voters “whether American culture and way of life” had mostly changed for the better or worse since the 1950s. The highest rate of dissatisfaction from any large cohort came from white evangelical Christians. Nearly three out of four, 72 percent, felt that American culture and way of life had mostly changed for the worse.10 Moreover, it was white evangelicals, not their religious brethren of color, who were so pessimistic.11 Robert Jones, the head of PRRI, commented: “The leaders of the Christian conservative movement won support by extolling the virtues of an orderly bygone era, where white Protestant Christian beliefs and institutions were unquestionably dominant and there were clearly defined roles for whites and nonwhites, men and women.”12

To race and gender, add hostility to government regulation of the marketplace.

Princeton historian Kevin M. Kruse in his book, One Nation Under God: How Corporate America Invented Christian America, documents the role of big money in infusing Christian identity in the United States with a pro–free market ideology. Most historians trace the power of Christianity in American politics to the Cold War era and national hysteria about a supposed mortal threat from “godless” communism. But decades before the 1950s, Kruse writes, “corporate titans enlisted conservative clergymen in an effort to promote new political arguments embodied in the phrase ‘freedom under God.’ … This new ideology was designed to defeat the state power its architects feared most—not the Soviet regime in Moscow, but Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal administration in Washington.”13

All of this combines to mean that white evangelical Christians are dream voters for the Right: staunch defenders of their right to remain racially segregated, committed to gender hierarchy, opposed to homosexuality, and often led by those Kruse terms “new evangelists for free enterprise.”

Mike Podhorzer, the political director for the AFL-CIO, the nation’s largest labor federation, has been waving his arms to get the Left to think through the implications of the white evangelical Christian voting bloc. Partly it’s the numbers. As Podhorzer notes, “White Evangelicals made up 20 percent of the 2016 electorate, and voted 77 to 16 for Trump. How big is that? By themselves, White Evangelicals canceled the margin that African Americans and Latinx voters provided Clinton.”14

The more important implications, though, extend to the Left’s strategy for building an enduring coalition. Using bold to emphasize his point, Podhorzer asks, “How much different would the current political debate be if ‘White Evangelicals’ replaced ‘white non-college’ to describe Trump’s base?”15

If Trump’s base is “white non-college,” often translated as the white working class, this suggests a sharp need to change course for Democrats. First, this group is huge: white non-college voters made up 44 percent of all voters in 2016. Second, the Democrats lost this group by a devastating margin, 28 percent for Clinton compared to 64 percent for Trump.16 That sort of margin implies the Democrats are simply out to lunch in terms of the interests and values that matter most to this indispensable group of voters.

But what if Trump’s base is white evangelical Christians? Correctly perceiving Trump’s base as white evangelical Christians should give the Left more confidence that it understands the concerns of the white working class. The Left is competing far more effectively for this group than most recognize—when one subtracts out evangelical Christians. Podhorzer calculates that without these voters, 42 percent of whites without a college education voted for Clinton, compared to 51 percent for Trump. In other words, the gap among working-class whites goes down from losing by 36 points to losing by a more competitive 9 points.

The power of the white evangelical Christian bloc should also change the debate about the role of white women in supporting Trump and the Right. Many assumed that white women would help Clinton to shatter the ultimate glass ceiling, especially against the boorish Trump. Then the exit polls showed Trump winning among white women by 9 points, a crushing victory that stunned many. As it later turned out, these polls were wrong. More careful study showed the margin for Trump was 2 percent, a virtual tie. Still, all across the Left and especially among feminists, many wanted to know how so many white women could support a Neolithic man. That’s the wrong question.

Writing in the Cook Political Report and drawing on Podhorzer, Amy Walter observes that here, too, it’s evangelical Christians driving the voting pattern. “Among women, if you remove evangelicals, white women with and without a college degree have the same (very low) opinion of the president,” Walter writes. Subtracting out evangelical women, Trump’s approval among white women without a college degree was a punishingly low 35 percent, and among college-educated white women it was even lower, 30 percent.17

Putting white evangelical Christians at the center of the Right’s base makes clear that the political advice for Democrats to tack rightward to win more support is highly questionable. In the short to medium term, the Left will not make more than marginal inroads into the white evangelical Christian voting bloc. In contrast, the Left can—and already does—compete effectively among white voters who are not evangelical, including among the white working class and especially with white women.

Understanding Persuadables: Most of Those in the Middle are Not Centrists

Three in five voters are in the convergence zone between the clashing Right and Left weather fronts. Does winning significant support from voters in the middle require that the Left compromise on its boldest aspirations? It’s common to argue yes. Very often, politicians and pundits laud “the middle” as a center of moderation, a place where the extremes of the wings are thoughtfully and reasonably balanced. The imagery of Left, Right, and Center certainly feeds into this. There’s a strong assumption that the middle is moderate, thoughtful, and, well, centrist.

A report issued in October 2018 by More in Common, a research group operating in Europe as well as the United States, illustrates this tendency. To be sure, their research findings paralleled those in the race-class narrative project. More in Common found that two-thirds of Americans, 67 percent, form a middle that is “considerably more ideologically flexible than members of the other groups.” “For instance,” the report said, “82 percent of Americans agree that hate speech is a problem in America today, but 80 percent also view political correctness as an issue.” They seemed to find what the race-class project found: conflicting views in a shifting middle that could go either way, in contrast to more consistent commitments among progressives and reactionaries. As the report stated, “members of the ‘wing’ groups (on both the left and the right) tend to hold strong and consistent views across a range of political issues.”18

The problem comes in their interpretation of these findings. According to the report, wisdom lies with the middle. People in this range, the report said, share “a willingness to be flexible in their political viewpoints” and also “believe that compromise is necessary in politics, as in other parts of life.” They stand in contrast to “partisan tribes” that are “fueled by a culture of outrage and taking offense. For the combatants, the other side can no longer be tolerated, and no price is too high to defeat them.”19

Flexibility and compromise are desirable attributes. They imply thoughtful consideration of all sides and measured weighing of the issues. There’s certainly an argument for deference to sober reflection, careful balancing, and reasoned judgment. But More in Common provides no evidence this is what’s actually happening in the middle.

Against this unsupported assumption, a range of sources contradict the image of thoughtful centrism in the middle. Much of the field of social psychology revolves around studying the often minimal triggers that bring to the fore different ways of seeing the world.20 There’s also good evidence the middle is composed not by people who thoughtfully develop “centrist” views so much as by persons who pay relatively little attention to politics. The American National Election Survey routinely asks voters to identify themselves on a scale from liberal to conservative. Studying their responses, the political scientists David Kinder and Nathan Kalmoe show that little separates those who answer the question by selecting “moderate, middle of the road” versus selecting “haven’t thought much about it.”21 Likewise, the Right does not appeal to nuanced centrist positions. Republican strategists like Frank Luntz build frames that spark and reinforce the reactionary views circulating in the middle. Or recall Matt on government spending: he invoked welfare recipients ripping off the system, yet also said government should fund education, food, and shelter for everyone. This is not thoughtful moderation. This is contradictory thinking that can be tugged in either direction.

More in Common also errs by dismissing the wings as “polarized,” as if the fact of sharp disagreement is by itself disqualifying. But today’s polarization is not primarily a defect in temperament among people inclined to take offense or energized by outrage. We are a deeply polarized society, precisely because the Left and Right advance profoundly different views on what a good society looks like. One side generally believes everyone deserves dignified treatment, with no distinctions based on race, gender, national origin, religion, or disability. The other generally promotes hierarchies of humans, where some belong in this country and others don’t, some worship the correct god and others don’t, some conform to the gender roles supposedly commanded by nature and others don’t. Similar splits occur in views about whether government should help or get out of the way, whether the marketplace is rigged for the rich or rewards honest labor, whether the environment faces grave dangers or is just fine. At this moment, in this country, right now, we’re choosing between very different visions for our future—and just about everything is at stake.

This is not to slight the concerns expressed about extreme partisanship. There are certainly dangerous trends of deepening division and conflict. Moderation, compromise, flexibility, and empathy are more important than ever. But these are qualities of thought and behavior to which all should aspire, not substantive positions exclusively held by those in the center.

The responses uncovered by the race-class project suggest that the Left need not trim its sails and set aside core beliefs to appeal to the “centrists” between the Left and Right. Instead, the results suggest those in the middle already hold progressive views though they hold reactionary ideas as well. This implies that the Left can build a broad, cross-racial movement for activist government by connecting to the genuinely progressive visions of society already circulating in the convergence zone.

People of Color are More Often Persuadable than Members of the Left’s Base

It’s tempting to view people of color as a natural progressive constituency. But as the race-class research demonstrates, progressive and reactionary ideas cut across racial lines. Recall that when we tested the racial fear message, similar numbers of Latinxs, African Americans, and whites found the Right’s dog whistle message convincing.

Compared to whites, people of color more often want government to proactively create opportunities. They resemble the base in this respect. Also, people of color generally view activist racial justice groups positively, again closely resembling the base. In contrast, on economic individualism and the role of the wealthy in the economy, African American and Latinx views shift away from the base and toward a midway point between the base and opposition. In particular, Blacks and browns credit the notion that the wealthy create jobs and prosperity for everyone and that people of color who cannot get ahead are responsible for their own condition.22

Versions of this emerged in the race-class focus groups, where people of color often repeated stories quite close to the welfare queen narrative. In one instance, we asked two African American men in Virginia to respond to a remark made by former Republican Speaker of the House Paul Ryan when promoting cuts to social spending: “We don’t want to turn the safety net into a hammock that lulls able-bodied people into lives of dependency and complacency, that drains them of their will and their incentive to make the most of their lives.”23

We wanted to know whether they recognized it as a dog whistle. What do you think about this statement? the moderator asked.

“That is a lot of big words, but yeah, I just feel like it’s a great way of saying we don’t want people to have to depend on the government,” one man said.

The moderator probed, “When you say people, what kind of people?”

“Lower-class people. People who would depend on my government funds and stuff like that, and different programs that the government will offer assistance rather than go out there and work hard for it and get it on your own.”

Or listen to an African American woman and her Latinx friend in Cleveland. They’ve been discussing hard work and paying taxes when the conversation pivots to people abusing welfare.

“You’ve got people out here that have got five, six, and seven kids and they get Social Security and they get Section Eight and they get utility checks and they get food stamps.”

“Well,” asked the moderator, “do they fall under the welfare queen label then or no?”

“Yeah, I would say those people will,” the woman responded. “When you sit there and you abuse the system, because you go and get your kid and say they are too hyper and they have ADHD and they need pills and now I can go collect Social Security and now I can get Section Eight and now …”

She let the sentence trail, but her companion summed up the complaint in a single word: “Welfare.”

Despite such views, there’s little risk that large numbers of African Americans or Latinxs will start voting Republican. Compared to whites, far fewer people of color stand in the opposition camp. But this does not mean that voters of color can be taken for granted. The GOP is doing virtually everything in its power to drive up the impediments that people of color confront before they can actually vote.24 Partly because of this, though people of color overwhelmingly tend to vote Democrat, many who are eligible to vote ultimately stay home rather than face the voting gauntlet. As the Pew Research Center reported about the 2016 election, eligible nonvoters “were more likely to be younger, less educated, less affluent, and nonwhite. And nonvoters were much more Democratic.”25 In 2016, those not voting included a majority of Latinxs (52 percent) and a large minority of African Americans (40 percent).26 Reaching persuadable people of color is key to political engagement and voter turnout.

There’s a final reason not to take people of color for granted as part of the base. Dog whistling is a strategy of divide and conquer more than of whites over nonwhites. For politicians, the goal is to win elections, and many politicians are perfectly willing to pit nonwhite groups against one another. During the George W. Bush era, Republican Party leaders like Karl Rove thought that the party’s future lay in convincing a large plurality of Latinxs that African Americans threatened them, too. For the moment, Trump has blown up the plans to recruit many more Hispanics into the Republican Party.27 Those plans will certainly resurface. It’s also quite possible for the Right to win votes from African Americans or to depress Black voter turnout by building divisions around national identity, pumping up the idea that the newest waves of immigrants threaten “Americans.”28 Simply being a person of color does not insulate one from strategically crafted dog whistle appeals.

A Caution About the Base: Liberal Whites Remain Susceptible to Racial Fear

In addition to being a majority in the persuadable group, whites comprise a majority of those making up the Left’s base. There’s genuine good news regarding the racial views among whites voting Democratic, but also sound reason not to count on an unshakable commitment to cross-racial solidarity among liberal whites.

Four in ten whites voted for Hillary Clinton in 2016, and among these voters there are encouraging trends in their racial attitudes, according to researcher Sean McElwee. For instance, in 1994, two years into the Clinton administration, two-thirds of white Democrats favored reducing immigration. By the end of Obama’s presidency, less than one-third took that position.29 And on the question of whether the country needs to continue making changes to give Blacks equal rights, among Democrats the spread between white and Black views shrunk by two-thirds during the Obama administration, closing to 10 points.30 It’s still true that Black Democrats overall are more racially progressive than their white counterparts. But as white liberals shift leftward in their racial views, these groups increasingly agree on racial issues.31

Nevertheless, the progressive racial commitments of many liberal whites remain shaky. In 2013, PRRI used telephone interviews to ask whites whether they agreed or disagreed with this statement: “The idea of an America where most people are not white bothers me.” More white Republicans (18 percent) than white Democrats (11 percent) directly said they agreed.32 But PRRI suspected that people might hesitate to plainly admit racial discomfort in a phone conversation with a stranger. To overcome this, PRRI employed a separate survey technique that allowed people to indirectly express their views. Measured this way, the proportion of white Democrats registering racial discomfort tripled to levels slightly higher than among Republicans (33 percent to 30 percent). White Democrats may have hesitated to admit being bothered by an America where most people are not white, but in fact seemed slightly more agitated about this than white Republicans.

PRRI’s question about “an America where most people are not white” is hardly hypothetical. This is already a reality in many cities, regions, and states. Social psychologists Jennifer Richeson and Maureen Craig sought to measure the likely effect of this demographic shift by testing how whites react to census data.

Richeson and Craig found that when whites were presented with news stories about census projections, they expressed a greater preference for being with other whites, exhibited higher levels of pro-white bias, and demonstrated greater prejudice toward nonwhites.33 They also found that whites became more reactionary on racial policies, such as their views on immigration and affirmative action, as well as regarding nonracial issues, for instance military spending.34 “Making the shifting U.S. racial demographics salient,” they concluded, “leads whites to perceive greater threat to their racial group’s status, which motivates them to increase their support for a variety of conservative positions.”35

Craig and Richeson were careful to interview “self-identified politically independent white respondents.” In other words, Richeson would later explain, “The point is that people who think of themselves as not prejudiced (and liberal) demonstrate these threat effects.”36

Why did whites shift rightward when thinking about demographic change? In one of their experiments, Craig and Richeson showed whites a mock news article about changing racial demographics, but they also varied the test, with a second version reassuring whites that they would remain economically dominant. In this second version, they added a sentence indicating that “White Americans are expected to continue to have higher average incomes and wealth compared to other groups.” When reassured of their continued economic preeminence, whites no longer shifted rightward. “And that’s how you know it’s status threat,” Richeson explains. It’s not the changing numbers that push whites rightward, but a fear they will lose their position at the top of the racial pile.37

Additionally worrisome, it took remarkably little to induce these negative effects. Even a slight prod could push liberal whites toward racially tinged political conservatism. Ryan Enos, a professor of government at Harvard, speculated that subtle intrusions on people’s racial awareness could generate significant shifts in their views. To test this, he sent Spanish speakers to commuter rail stations in some of the predominantly white towns around Boston. The testers were instructed to merely ride the train like any other passengers. Separately, before and after sending the testers, Enos surveyed passengers about their attitudes toward immigration. “After being exposed to the Spanish speakers on their metro lines for just three days,” he found, “attitudes on these questions moved sharply rightward.” Enos concluded, “The mostly liberal Democratic passengers had come to endorse immigration policies—including deportation of children of undocumented immigrants—similar to those endorsed by Trump in his campaign.”38

These findings extend to younger whites as well. In the PRRI study on the number of whites who were “bothered” by the prospect of a minority-white country, whites aged 18–49 reported the lowest levels of concern when asked their views directly. But when they could express their discomfort indirectly, the difference between whites younger and older than fifty evaporated.39 Likewise, Richeson and Craig also found similar effects without regard to the age of the respondents. “When it comes to our interpersonal biases,” Richeson says, “it’s simply not true that we just need to wait for the few old racist men left in the South to die off and then we’ll be fine. The rhetoric for racism is still in place. The environment for racism is still there.”40

The Left’s task is to build a multiracial coalition to elect leaders who will promote racial justice and economic fairness. It’s a mistake to translate this into a simple formula that calls for winning back the white working class, or appealing to supposed centrists in the middle, or depending on people of color as a natural base or on liberal whites as firm racial allies. The challenge instead is to encourage persuadables to align with an energized and unified progressive base. Broad popular support for rejecting racism and building solidarity will come from shared ideas and values.

So how can the Left build cross-racial solidarity? One strategy is to center racial justice.