Should the Left Lead with Racial Justice?

When Hillary Clinton ran for president in 2016, the dog whistling employed by her husband in the 1990s came back to bite her. On the campaign trail for his wife, Bill Clinton encountered a decidedly mixed reaction from the African American community. Older generations, particularly in the South, continued to feel warmly toward the white man whom some used to jokingly call the first Black president. But especially among younger African Americans in the country’s cities and suburbs who came of age amid the fallout of Bill Clinton’s tough-on-crime agenda, his contributions to mass incarceration damned him. He had expressed regret—for instance in 2015, when he admitted that the crime bills he promoted “overshot the mark.” Nevertheless, Clinton still defended those policies, and his faint regrets mainly served to further antagonize his most vociferous critics.1

But it wasn’t just transferred hostility that tarnished Hillary Clinton’s progressive credentials. She had herself actively participated in 1990s dog whistling, and she paid a price.

Michelle Alexander, whose book The New Jim Crow helped generate waves of activism against mass incarceration, directly indicted Hillary Clinton. Alexander published a forceful essay in The Nation in February 2016, bluntly entitled “Why Hillary Clinton Doesn’t Deserve the Black Vote.” The short answer: “From the crime bill to welfare reform, policies Bill Clinton enacted—and Hillary Clinton supported—decimated black America.”2 Alexander was unsparing in her criticism, writing that “[Bill] Clinton was the standard-bearer for the New Democrats, a group that firmly believed the only way to win back the millions of white voters in the South who had defected to the Republican Party was to adopt the right-wing narrative that black communities ought to be disciplined with harsh punishment rather than coddled with welfare.”

Hillary also deserved blame, Alexander argued, because “she not only campaigned for Bill; she also wielded power and significant influence once he was elected, lobbying for legislation and other measures.” In particular, Alexander criticized Clinton for selling criminal measures by casting Black children as ferocious animals. “They are not just gangs of kids anymore,” Alexander quoted Clinton as saying. “They are often the kinds of kids that are called ‘super-predators.’ No conscience, no empathy. We can talk about why they ended up that way, but first we have to bring them to heel.”

This was a devastating quote, crystallizing in a manner no numbers or policy discussions could match precisely how the Clintons played to white racial fears by dehumanizing Blacks. It should not have been that much of a surprise, then, that two weeks after Alexander’s essay appeared, a Black Lives Matter activist crashed a private Clinton fundraiser, unfurling a banner that read “We have to bring them to heel,” and challenging Clinton to apologize for mass incarceration.

“You called people super-predators,” said twenty-three-year-old Ashley Williams, resisting pressure to stay silent from the donors gathered at the intimate house party.

“Explain it to us,” Williams persisted. “You owe Black people an apology.”

In her response, Clinton conveyed more than anything else annoyance at the interruption. She tried to stick with her prepared remarks, though Williams would not relent. Clinton finally gave up and addressed Williams directly, with a response that was both empty and patronizing: “You know what? Nobody’s ever asked me before. You’re the first person to do that, and I’m happy to address it, but you are the first person to ask me, dear.”

Then, as security removed Williams, Clinton said “Okay, back to the issues.” Those issues seemingly did not include her role in 1990s dog whistling.3

If Hillary Clinton was evasive, at least she was relatively restrained. Not so Bill, when two months later Black Lives Matter activists held up signs at a Philadelphia rally to challenge him about Hillary’s support for mass incarceration. Bill doubled down.

“I don’t know how you would characterize the gang leaders who got thirteen-year-old kids hopped up on crack and sent them out on the street to murder other African-American children,” Clinton said, wagging his finger at the protesters. “Maybe you thought they were good citizens. She didn’t. She didn’t. You are defending the people who killed the lives you say matter,” he exclaimed. “Tell the truth. You are defending the people who caused young people to go out and take guns.”4

Hillary Clinton seemed unprepared to answer for dog whistling’s harms to Black communities. Apparently no one on her staff had communicated to her the core of Alexander’s indictments, though she was one of the most well-known Black activist-intellectuals in the country, or at a minimum had reminded Clinton that she was on record equating Black children with vicious dogs.

Clinton was not the only presidential candidate confronted by racial justice activists. In addition to steady protests at Trump rallies, activists pushed virtually every Democratic candidate to speak to mass incarceration and other forms of systemic violence against Black and brown communities. Bernie Sanders faced these calls to account, and like Clinton stumbled. As Sanders rose to speak at the summer 2015 convening of Netroots Nation, a huge progressive conference, Black Lives Matter protesters seized the mic to talk about the jailhouse death of Sandra Bland, who was arrested after a minor traffic stop in Texas and later found hanged in her jail cell. The activists challenged Sanders to say concretely what he would do to address law enforcement violence. But Sanders “was defensive and cranky toward the protesters,” reporters noted, answering back, “Black lives of course matter. But I’ve spent fifty years of my life fighting for civil rights. If you don’t want me to be here, that’s okay.”5

Activists were also confronting Democratic leaders around immigration. In the fall of 2017, for example, protesters swarmed a press conference by then–House minority leader Nancy Pelosi, shouting her down with accusations that she was bargaining with Trump to increase deportations. Pelosi seemed stunned, since she was hoping to trade increased deportations for legislation protecting young people brought to the country without documents—the so-called Dreamers, a group that included some of the protesters. The activists, however, rejected the notion that their protection should be gained by sacrificing others, often family members. “You met with Trump and you call that resistance?” they chanted. “This is what resistance looks like!”6

The fire and fury on the anti-racist Left presents a direct challenge to politics as usual for liberals. Even strong racial reform proposals seem unlikely to assuage the demands of activists chanting “united we dream” and “Black lives matter.” Clinton and Sanders offered some of the most progressive reform proposals of any Democrat in decades, and yet found themselves under fierce protest. More than policy ideas, the activists demanded a genuine commitment to racial change. Clinton struggled to convey steadfast concern, seeming not even to realize the human costs of her prior offenses, or perhaps not willing to acknowledge—in the midst of the most important political campaign of her life—the cynicism and social destructiveness of her past politicking. Sanders repeatedly rejected placing racial justice on par with economic justice, insisting that repairing the economy should be everyone’s first priority. For however strong their policy prescriptions, many activists remained unconvinced of the Democratic leaders’ actual dedication to racial justice.

It’s hard to imagine Democrats on the national level returning to Bill Clinton’s style of dog whistling without sparking a full revolt among racial justice activists. Moreover, this is not just a matter of a few activists; they shape the views of the much larger progressive base. “The progressivism of the base is being driven by the rise of mobilized racial justice groups like Black Lives Matter and the ‘Dreamers,’” Sean McElwee reports. “Many young voters have warmer feelings toward movements like Black Lives Matter than towards established Democratic politicians.”7

This emerging radicalism among young people likely contributed to voting dynamics in 2016. Among the Black voters who stayed home, it was overwhelmingly those aged 18–29, about half of registered Black voters in this age group, who ultimately decided not to vote.8 Or if they didn’t stay home, a pivotal chunk put the pox on Democrats by casting votes for third-party candidates. Cornell Belcher is a prominent Democratic pollster associated with Obama’s campaigns, who also worked on our race-class research. As Belcher pointed out, “when you have between 6 to 9 percent of younger voters of color breaking 3rd Party in their ‘protest vote,’ that kills the Democrat’s chance to reach Obama’s margins, most notably in places like Florida, Michigan and Wisconsin.”9

No Democratic resurgence is possible based on a game plan that expects racial justice movements to set aside their core concerns. Or, as Michelle Alexander put it, “If progressives think they can win in the long run without engaging with Black folks and taking history more seriously, they better get Elon Musk on speed dial and start planning their future home on Mars, because this planet will be going up in smoke.”10

The question, then, is how the Left should engage Black folks and other people of color.

Activists currently put pressure on Democratic candidates to make helping communities of color a central commitment. There’s a newly powerful demand that Democrats stop pretending their cell phone batteries have died when it comes to answering calls for racial justice.

But as an electoral strategy, leading with racial justice is clearly risky. The Right constantly warns that liberal government and the Democratic Party care more about people of color than about whites. Coming out strongly in favor of racial justice—endorsing reparations, or calling for sweeping reforms to policing, or for abolishing Immigration and Customs Enforcement—provides the Right handy ammunition. Should the Left do so anyway?

This chapter considers the “racial justice” approach advocated by many activists focused foremost on helping communities of color. To be clear, there’s no argument here that the Left should abandon communities of color to win over whites. The next chapter examines the limits of colorblind economic populism. The point there is not to give up on progressive economic policies, but to explain why focusing on economic populism at the expense of talking about racial justice ensures that neither can be achieved. Likewise, here the argument is not that progressives should jettison efforts to promote racial justice. The argument is that the current way of explaining racial justice as a goal makes it harder to get there, at least in the context of electoral politics.

Talking to Whites About Racial Justice

It’s conventional wisdom among many Democratic strategists that talking about racism against communities of color fails with white voters. Unfortunately, this is correct. The race-class narrative project explored in the focus groups how to talk to voters about racism. The reactions quickly confirmed that liberals rightly conclude that they should avoid talking about racial justice in ways that implicitly center white-against-nonwhite discrimination.

The most positive response the project elicited from a participant in a white focus group was indifference. In Atlanta, one woman seemed to speak for the other eight around the oval Formica table when she said: “We’re all white. Race doesn’t affect us day to day and so most of us don’t have to worry about that.” She knew racism mattered. She had been relaxed, reclining in her chair, but to broach this subject, she leaned forward earnestly: “I think it’s important to remember that that’s an issue that some people have to deal with every second of every day, they always have to keep race in mind,” she said. But still, it did not matter much for people like them. “I think for white people, it’s probably not going to be the thing that’s keeping you up at night,” she concluded.

Other reactions confirmed that whites tend to filter narratives about racism against people of color by asking what this means for them as white people. Another woman in the Atlanta group responded candidly that fixing racism isn’t good for whites because that might limit their opportunities. “When we talk about diversity and race and how to minimize the difference between the whites and blacks … for example in college admissions … that case can hurt white people, because they will not be chosen to be admitted to college for the diversity reasons.”

Other whites responded defensively to discussions of racism. In some focus groups, whites seemed to translate the conversation about how racism harms people of color into a perceived indictment of white people. Pushing back against this, a white man in an Ohio focus group—not the group with Matt and Tom—cast about for ways to spread the blame. He implied that many racial groups have participated in slavery and genocide. “Everybody equates all the slavery to the white man,” he said. Then, apparently referring to practices of slavery in the history of African nations, he added: “Whereas when we go over there, yes, they were doing the exact same thing.” He also extended allegations of barbarism to Native Americans, in the process recasting domination by whites as benevolence. “We try to give a lot of land back to the Native Americans,” he said, “whereas the Native American tribes were warring tribes against each other and would enslave, rape, and pillage each other as well.”

Visceral rejection was common when the topic of racism was on the table. “I hate the entire thing because it’s fearmongering, is what it’s doing,” said another participant in the Ohio focus group of white men. Another, who might describe himself as colorblind, responded that the topic of racial discrimination “bothers me.” He explained: “When you keep talking about racism … I don’t really think that’s it, it feels like one of those fake dividing lines they’re throwing out for us to chew on. It’s like ‘it’s all about skin color.’ It’s not, it’s really not.”

We varied our messages to explore different approaches. In one version, we encouraged whites to recognize that some of them belong to groups that were themselves prior victims of anti-immigrant racism. Immigration activists sometimes offer stories along these lines, hoping to show today’s whites that their own ancestors faced discrimination decades ago when they were the unpopular immigrants of the time.

Again, however, many whites reacted negatively, repeating in particular the charge that naming racism was divisive and possibly racist itself. The race-class project asked people their thoughts on this statement: “Italians were once slurred as without papers, an insult familiar to Latinos today. The Irish were accused of gaming the system, a charge still made against black people. Asian Americans are seen as foreigners in their home.”

“That just goes against my grain,” said one participant in a focus group of white men and women in California’s rural Central Valley. “In New York when they came off the ships, it was so divided and they were very racist against each other. I don’t think everybody was but it was a very divided country back then … and I don’t like that division.” He seemed willing to concede there had been racism in the past. But making any comparison to the present seemed to strike him as offensive.

Speaking next, another man clarified what was bothering many of them: “I agree with a lot of what [he] said. It just reeks racism all throughout this statement.”

The moderator followed up, “What do you mean it has racism?”

“Well, the racial references to various people here,” he explained. “Italians without papers. Latinos. Derogatory terms. That’s the way it was. I think it’s just referring to how it was. That’s the reality but that’s what’s frustrating. And it’s trying to redirect it into current times.… I’m not saying racism isn’t there but it’s not as prevalent, at least publicly prevalent.”

Lurking in their remarks was the sense that talking about racism, even racism in the distant past, is itself racist and divisive.

This resistance to history will likely come as a big surprise to many in the advocacy community. In laying the groundwork for messaging around race and class, Anat Shenker-Osorio interviewed several dozen union leaders, policy advocates, progressive storytellers, and racial justice organizers. Many favored educating the public about the past. “Our most compelling argument is that history unremediated has consequences,” said one. Another added, “if we’re really speaking about a society that deals with the historical and the current legacy of racism, you have to have an education program.” (It’s not possible to credit these speakers by name because they were promised anonymity, which was important so they could speak freely rather than feel pressure to repeat their organization’s talking points.) I had started from this perspective, too. Recall that my initial approach with the unions involved day-long history lessons.

The focus groups revealed that people were uninterested in talking about past injustices. Celinda Lake was not surprised, as she had seen this resistance to history before. Based on her polling experience, Lake observed that Americans prefer to look forward rather than back. With racism in particular, though, yet another dynamic became apparent. The disinterest in history among whites when it came to racial issues seemed a form of self-defense.

In the various focus groups we conducted, we often asked about Jim Crow segregation—the separate and inferior schools, bans on interracial marriage, and other laws that for decades humiliated and oppressed African Americans. We hoped to gauge people’s comfort in thinking about racism as structural, rather than simply in terms of individuals mistreating others. In a striking moment, one of the Ohio white men we interviewed in a large focus group claimed that “Jim Crow wasn’t real.” The flat denial seemed like a sudden flare of fringe internet propaganda, until it became clear no one in the group would contest this claim. Instead, one fellow responded: “I mean I have never researched it because I don’t want to know about it to be honest.” This admission says volumes about how numerous whites respond when confronted with injustices perceived as only affecting communities of color—“I don’t want to know.”

People of Color Are Not Happy to Talk About Racism, Either

We had anticipated that talking about racism would prove challenging for whites, and it was. More startling, even people of color did not want to hear about it.

In this, they differed dramatically from many in the advocacy community. Not only did activists want to talk about history, they were also comfortable and insightful when talking about “racism.” Indeed—this will become important later—many advocates already understood racism could be a class weapon, as in this comment: “Race is a way of categorizing human beings that was invented a couple of centuries ago to create a hierarchy of human value for political and economic and social goals.” Moreover, advocates readily singled out whites as the racially favored social group, with explanations like this: “Racism is the ways in which some groups of people, especially white folk—well, not especially, specifically folks who read as white—have set up systems of power vis-à-vis people who don’t appear white, or are not coded as white.”

This direct and sophisticated discussion of racism was almost entirely missing from the focus group conversations, even among people of color. In fact, people of color in our focus groups tended to resist all express discussions of white-over-nonwhite racism.

We presumed the statement comparing discrimination today to racism against European groups decades ago might resonate with Asian Americans and Latinxs. But a person in the Asian American focus group in Los Angeles said it felt like a way to build connections among “ethnic people” at the expense of white people, “almost like reverse racism.” A member of the Latinx focus group in Los Angeles said the comparison was “very judgmental in regards to race. It’s describing Asian Americans and then Italians and Latinos and Black people.” The moderator pressed for clarification about what specifically bothered her. “I guess just like the Italians were once here without papers. That’s kind of racial, like why would you say something like that. It’s offensive.… As much as we don’t want to point at certain classifications of people, that’s all this thing is doing, whether it be past or present it’s just a tag.” She sounded a lot like the white guys in the Ohio focus group who felt that directly talking about racism was almost racist itself.

Among African Americans, we experimented with different approaches and encountered a range of responses. When we tried presenting racism as a structural issue, participants often balked. Asked if “certain power structures” limit African Americans, one woman in Columbus, Ohio, disagreed, putting the responsibility on Black people instead, “because I think that passivity has a lot to do with why we may not get ahead,” she said. “I think that is what we tell ourselves, that it’s not possible. Sometimes we don’t always have the courage to push past certain things.… We’ve been shown that anything is possible, but I believe we tell ourselves that we can’t.”

Rather than accept racism as a structural impediment to advancement, this speaker seemed to invoke the personal responsibility frame promoted by the Right. This perspective rests on a view of racism as nothing more than rare instances of interpersonal bigotry, and therefore as an illegitimate excuse for economic hardship in communities of color. Such views are in wide circulation. Recall, for instance, Tom describing talk among African Americans of slavery and its legacy as “a horrible crutch to not trying, not working, not fixing yourself.”

Unfortunately, similar stories downplaying structural racism and portraying poverty in African American communities as a matter of individual fault are also sometimes promoted by the Black leadership class.11 In her deeply affecting memoir, Patrisse Khan-Cullors, one of the cofounders of Black Lives Matters, describes living this: “We lived a precarious life on the tightrope of poverty bordered at each end with the politics of personal responsibility that Black pastors and then the first Black president preached—they preached that more than they preached a commitment to collective responsibility.… They preached that more than they preached about America having 5 percent of the world’s population but 25 percent of its prison population, a population which for a long time included my disabled brother and my gentle father.”12

Here’s another dynamic the race-class project encountered. We found that when we talked about racism as a problem for Black communities, many in the African American focus groups conveyed skepticism about whether anything would change. As someone in the Columbus session said: “You can have rallies and, you know, just do anything to try to make a change for the better, and whoever the powers may be, they’re going to do what they want to do, what they’re compelled to do anyway. We can demand, strike, boycott, whatever it is, but whatever the answer is at the end of the day that’s what it’s going to be. That’s just my opinion. I think they just don’t listen at all. We do a lot of walking and going down to the city council and all that but they don’t hear nothing.”

Others in the group nodded in agreement, with one adding, “Everybody that tries to stand up for something, for change, they die. Somebody gotta die. They go and stand up and—Martin Luther King, even presidents, John F. Kennedy—people who try to stand up for something they got killed, people scared.”

If political change was not possible, that seemed to give greater weight to the personal responsibility frame. From the same Columbus group, another individual said: “We chose Obama, but guess what happened? More people started getting killed. More police started killing more Black people.… So it ain’t about the leaders, it’s about you yourself.”

If people were skeptical of change, they were also cynical about our effort to talk to them about racism, suspecting that Black people had been singled out for a conversation that amounted to a form of pandering. At the end of one Black focus group in Atlanta, a participant expressed that very directly: “I feel like this is the Black script. I don’t know how many groups you all have typically in here, but this feels like ‘This is the Black group, so let’s give them the Black script.’ ‘This is the Indian group.’ And then the white group.”

The Racial Justice Narrative

The pushback against a racial justice narrative was so strong in the focus groups that when we crafted and tested messages in a national survey, we omitted that frame. When we later ran surveys in California and Indiana, we returned to and tested a message built around fighting racism against people of color. As with the other messages, the race-class project built the racial justice narrative from language and arguments in common use by advocacy groups.

Why call this the “racial justice message”? It’s the term that most activists use to describe their narrative, their policy proposals, and their ultimate aim. To reiterate, the race-class project does not urge turning away from racial justice policies or racial justice as a foundational goal. The debate centers on the power of the different narratives to generate broad support for fundamental change.

Racial Justice

America is meant to be a nation founded on an ideal—that all are created equal. But from our founding, America has denied this promise to people of color and refuses to honor it still today. We see this in how police profile, imprison, and kill Black people. It’s the reason why families of color struggle with lower wages and virtually no inherited wealth. And It’s present in how we exploit immigrants’ labor while denying immigrants’ rights. To make good on our belief in liberty and justice for all, we must transform our criminal justice system, immigration policies, and economy to dismantle the barriers to well-being and opportunity for people of color in America.

Notice how the racial justice frame presents racism as something that harms people of color and implicitly something done by white society. This white-versus-nonwhite framing typifies how most progressives think about racism—understandably so, because white racial supremacy is a defining feature of racism’s history in the United States. In short, this message says the route forward is to challenge white society’s racism and to focus on helping communities of color. It centers structural racism as the problem and people of color as the solution’s intended beneficiaries.

How did people we surveyed respond? The base was comfortable with this message, although they didn’t love it. In both California and Indiana, the base thought more than half of the nine alternative race-class narratives we tested were more convincing. On the other hand, they did find the racial justice message more convincing than the narrative promoting colorblind economic populism. They were also much more positive toward it than to the dog whistle racial fear message. In short, if the goal is to win over the base, Democrats could go with either a race-class message or with a racial justice message. But this was among the base. What about among persuadables?

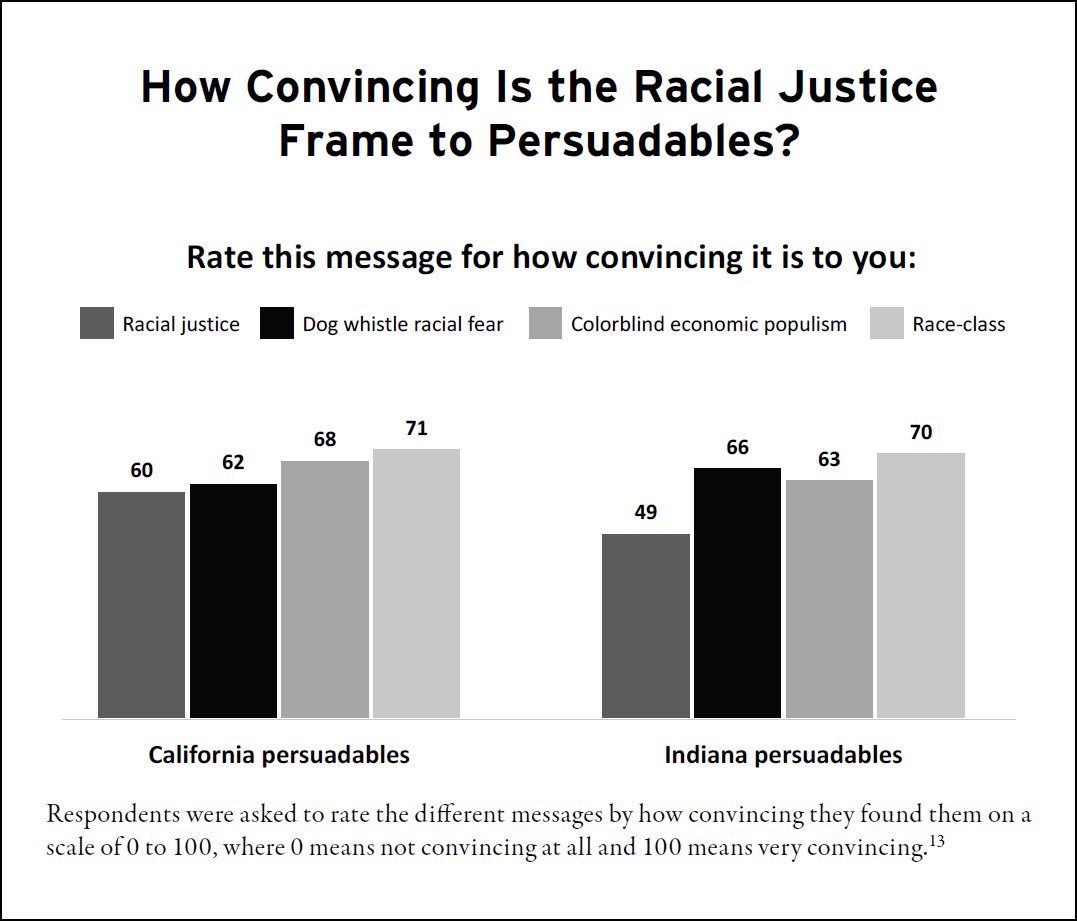

Even in a progressive state like California, the persuadable middle found the racial justice frame slightly less convincing than the opposition racial fear message, and significantly less convincing than colorblind economic populism and all nine of the race-class messages. In the more hard-fought swing state of Indiana, persuadables found the racial justice message the least convincing by a wide margin. Indeed, although persuadables tend to agree with most positions, in Indiana the rating for the racial justice frame stayed below the basic “convincing” threshold. In short, the research suggested that the racial justice message loses persuadables, potentially by a lot.

Understanding Clinton’s “Stronger Together” Campaign Through the Racial Justice Frame

It may seem surprising, given the protests against her by racial justice activists, but Hillary Clinton modeled her 2016 campaign around racial justice. In turn, the reactions to the racial justice frame encountered in the race-class research may shed some light on how voters responded.

To see that Clinton ran a racial justice campaign requires seeing how far Clinton traveled not just from the 1990s but from her campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination in 2008. In her match-up that year against Barack Obama, Clinton seemed to prioritize winning white voters. For instance, Clinton claimed during the 2008 primaries that support among whites made her a stronger presidential contender: “I have a much broader base to build a winning coalition on,” she explained in an interview, citing a poll that she said “found how Sen. Obama’s support among working, hard-working Americans, white Americans, is weakening again, and how whites in both [Indiana and North Carolina] who had not completed college were supporting me.”14 Clinton’s equation of “hard-working Americans” with “white Americans” struck many as a form of dog whistling.15 Perhaps it was. Or maybe this linkage was merely an unconscious slip, one that revealed the cultural power of the stereotypes contrasting supposedly hardworking whites and lazy Blacks. What was no mistake was Clinton’s observation that race gave her an edge. Pushed by reporters on whether her remarks were racially divisive, Clinton insisted that “these are the people you have to win, if you’re a Democrat, in sufficient numbers to actually win the election. Everybody knows that.”16

Obama’s triumph that year made it clear that “everybody” was wrong, and eight years later, Clinton embraced a different approach. Obama’s election and reelection hardly offered a clear lesson. Obama’s 2008 victory came against the backdrop of economic calamity, conditions under which voters routinely turn out the incumbent party. In a possible warning sign, Obama won his second term with fewer votes than his initial victory, a rarity, and white voters in particular shifted away from Democrats during Obama’s presidency. Still, Clinton’s view of how to assemble a winning electoral coalition evolved markedly.

In 2016, Hillary Clinton did not seek white voters at the expense of people of color. She apparently assumed she would get as many white votes as did Obama. Instead, anticipating some decline in support from African Americans after the excitement of voting for a Black president, Clinton formulated an electoral strategy predicated on energizing voters of color as well as women and millennials—the so-called New American Electorate.

Clinton kicked off her campaign with policy speeches proposing progressive reforms in the areas of mass incarceration, mass deportation, and voting rights. Many of her proposals went beyond positions taken by Obama, who feared creating the impression he especially cared about communities of color. In other words, Clinton proffered the most reformist racial justice policies a Democratic candidate for president had put on the table in decades. She might not have been the most credible messenger for racial justice, given her connections to Bill Clinton’s racial pandering to white voters. Still, she used the racial justice frame to talk to the American electorate.

In her Democratic convention speech, for instance, Clinton promoted the campaign message that we were “stronger together.” To be sure, she referenced groups that typically code as white, for instance the working class and law enforcement. But Clinton seemed to stress the need for more marginal groups to come together. “Let’s put ourselves in the shoes of young Black and Latino men and women who face the effects of systemic racism, and are made to feel like their lives are disposable,” she said. Point by point, to raucous cheers and applause from the activist base who made up the crowd, she listed additional groups needing protection: We must defend “civil rights … human rights and voting rights … women’s rights and workers’ rights … LGBT rights and the rights of people with disabilities!” The speech and the campaign covered much more ground than this; the passages highlighted here are far from the sum total of what Clinton promised at the convention or as a candidate on issues as varied as Wall Street, the environment, women’s rights, and even the relevance of her own biography. Nevertheless, it seems fair to say Clinton sought to assemble a majority of minorities.

Moreover, within this coalition, Clinton gave pride of place to voters of color. It might seem she compiled an inclusive list of aggrieved groups, with no priority among them. But racial justice was foremost in the issues she stressed. Clinton did so because her campaign understood that the “New American Electorate” offered a coded way of talking about people of color as the cutting edge of Democratic politics. The phrase includes women and millennials, but those larger demographic groups are progressive primarily because of the number and influence of people of color within those broad cohorts. “Stronger together” may have called for people to protect a raft of marginalized social groups, but Clinton put a special emphasis on fighting systemic racism, mass incarceration, mass deportation, minority voter disenfranchisement, and, last but not least, the racism coming from the Trump camp.

Clinton won the popular vote but lost the race for the White House. Too many dynamics were at play to identify a predominant explanation for her loss. Still, without relitigating Clinton’s campaign, the race-class research offers some insights into the impact her racial justice narrative might have had on voters.

If the progressive base responded to Clinton’s racial justice frame as they did to the version we tested, they found Clinton’s focus on remedying structural racism compelling. The cheers in the convention hall were real. The progressive base genuinely supports helping communities of color by redressing institutional racism.

But the response of the persuadables on the survey, and even more so the reactions in the focus groups, suggest that Clinton’s racial frame ruffled many. The focus groups predict there would have been a range of negative responses among whites—from indifference to defensiveness to visceral anger at a perceived personal attack. In other words, in seeking to build a progressive movement by leading with racial justice, Clinton should have anticipated real challenges in generating enthusiasm among white voters. Protecting the rights of everyone was her intended theme. But to whites watching Facebook snippets of Clinton’s convention speech, that may have been supplemented with everyone but me.

And regarding voters of color, the intensity of our focus group responses suggest Clinton should have anticipated skepticism and cynicism. Why should they believe structural racism was really going to ease? How could they be sure Clinton wasn’t drawing on her own “Black script” just to win their votes? As it happened, many voters of color stayed home.17 Clinton may have said we’re stronger together, but large numbers of nonwhite voters seemed unmoved. No doubt many factors contributed. But it’s likely that the racial justice frame designed to reach communities of color in fact fell flat with large segments of its intended audience.

Clinton’s 2016 campaign seemingly confirms the conventional wisdom that telling a political story that implicitly condemns racism against people of color alienates many white voters. The race-class research suggests it also struggles to carry communities of color and loses the very valuable persuadable middle. But what follows from this? Two very different lessons are on the table:

1) Stop talking about racism entirely.

2) Talk about racism differently.

After 2016, most Democratic strategists defaulted back to lesson one, a race-silent approach that the party has been stuck on for decades. We turn to that option next.