THE 10 HABITS OF HIGHLY SUCCESSFUL HUNTER-GATHERERS

Take responsibility

Take responsibility

Be selfish

Be selfish

Build a tribe

Build a tribe

Be present

Be present

Be curious

Be curious

Trust your gut

Trust your gut

Pick your battles

Pick your battles

Get over it

Get over it

Sharpen your spear

Sharpen your spear

Be affluent

Be affluent

Attitude is a little thing that makes a big difference.

WINSTON CHURCHILL

BEFORE WE GO ANY FURTHER, let’s pull back for some perspective. It’s important to step out of our modern mindset and think more like a hunter-gatherer. It’s really not that much of a stretch. It’s still there, still part of who we are if we’re willing to accept it—and access it. When we bring a primal perspective to our lives, we can begin to make key connections. We can begin to see our choices differently.

Let’s start with our inner chatter. We spend a lot of time in our heads these days. We mentally catalogue our to-do lists and check off logistical notes throughout the day. We emotionally narrate our experiences, respond to what is said and not said, analyze every nuance of our conversations, and even relive past interactions, often judging or beating ourselves up in the process. Then there are the big questions of ongoing self-talk we use to define ourselves. It’s interesting that we put such a substantial premium on “finding ourselves.” We use this phrase to suggest an essential quest or—in the absence of knowing—a crisis. We ask, “Who am I?” “What is my life about?” “What should it be about?” “What makes for a happy, fulfilled, balanced life?”

As common as the questions are, satisfactory answers all too often elude us. In the end, most of our self-chatter leads us to feel lost, discontented, even defeated. For all our self-analysis, why do we seem to be more confused about who we are and less satisfied with what we have than previous generations?

The problem is we overthink, we overreact, we self-criticize, and we self-judge … because we can. That’s the irony. We get bound into distorting our own realities. We cut ourselves off from what’s essential. Tens of thousands of years ago, we evolved some pretty elaborate cognitive abilities like self-awareness and metarepresentation. And with those gifts, we learned to process what-if scenarios and grasp the emotional complexity of—and separateness between— ourselves and others. The adaptive benefits of these developments included being able to assess our own motives and imagine those of others—for example, reasoning that your buddy will probably be upset if you strike up a relationship with his lady friend. And mulling over all kinds of hypotheticals in selecting the best course of action such as deducing that it is probably safer to kill a mammoth with a projectile spear rather than to run up on it and jab it with your stone-carved knife.

Though beneficial much of the time, these cognitive abilities can become intellectual and emotional traps when they aren’t brought into check by the social environment that first defined them. Our brains formed in a simpler time and environment. It was pretty clear what was real and what wasn’t; and what wasn’t real was inconsequential. Today, we make what isn’t real our reality. We literally dream up ways to make our lives more difficult and miserable. We spend hours obsessing in front of mirrors when our ancient ancestors never in their lives saw a full image of their own reflection. We compare ourselves to digitally enhanced people on magazine covers, who in reality have no connection to our lives. We secretly eye the count of Facebook friends of people we know, convinced our own social circles must be lacking. We relive the anguish of past insults, refusing to acknowledge that the events are done, and hence current pains are self-initiated. We worry needlessly over possible future events that exist for now only in our thoughts, and yet they cause us to back off or shut down. In going down these imaginary roads, we entertain thoughts of ingratitude, resentment, self-doubt, depression, and, in some cases, even suicide.

Once upon a time, self-reflection served a valuable purpose that was rooted in the stakes of survival. Today, it more often just gets in the way of authentic living with relentless self-chatter that distorts our own sense of wellbeing. It ultimately diminishes the experience of the present moment, and keeps us from giving our focus and energy to what can genuinely serve our health and fulfillment.

In fact, we can get stuck in self-talk as a confining, even sabotaging condition. When we follow the path of self-talk to its logical (or illogical) conclusion, we often act completely against our self-interest. Consider the concept of akrasia. It encompasses this irrational, confounding state of mind in which we wittingly throw caution, reason, and consequences to the wind in order to pursue a choice we know will be bad for us.

“Survival required that our ancestors regroup and forge ahead to the next challenge when they faced unfavorable circumstances.”

Examples of akrasia include dumping your healthful diet for an emotionally charged binge with a quart of chocolate ice cream. And then indulging in the guilt afterwards. Or in procrastinating on something important, such as putting off working on your tax return until the second week in April, or avoiding cleaning out the refrigerator until you’d rather throw out the Tupperware than open the lid.

We get it intellectually, but something illusory and emotional takes over. Strictly speaking, we know better. In fact, we know pretty much exactly what repercussions will befall us—financial trouble, relationships fallouts, job stress, health effects, and so on—but damned if we don’t go down that road anyway.

Some just shrug their shoulders and suggest it is simply human nature. Can we truly write off our responsibility so easily as chalking it up to “hominids will be hominids?” As much as we’re subject to evolutionary instincts, we generally have enough thinking skills on the higher order to pull ourselves back from the brink when we’re so inclined.

The fact is, we’re all subject to the conflicting impulses and better spirits of our human heritage. When we each consider what has caused us to act against our self-interest, what has held us back from embracing better choices at certain points in our lives, rarely does it ever come down to any neat, academic abstraction. Instead, it’s a long, intricate yarn of personal experience.

Part of self-control is self-understanding: knowing the circumstances that test your confidence, preempting the script that tends to play in your head when life gets tough or you have time on your hands. Only then can you divert the narrative, anticipate your needs, and genuinely tend to your weaknesses before they get the better of you. It’s about understanding that this, too, shall pass. The power to consciously steer your own self-talk today determines who, and what, ultimately directs your overall life story.

How, then, do we rein in this penchant for the self-talk that undermines genuine and healthy self-interest? How do we impose perspective and proportion on what ultimately matters? Try putting the focus of your self-talk against the backdrop of our Paleolithic ancestors, and see what it looks like. Chances are, the vast majority of your inner chatter will appear pretty inconsequential. When we reconnect with our fundamental roots and follow those habits, we are better able to assess what’s real and healthy and what’s just mentally contrived nonsense. We are able to cultivate a more balanced, focused, and stable sense of self. We are better able to fully appreciate the adage: Life is 10 percent what happens to us (chance) and 90 percent how we respond to it (choice).

In making the Primal Connection, there are inevitably layers of modern clutter and distortion to shuck. The process obliges us to release ingrained behaviors— like our inner dialogue—that hinder opportunities for pleasure, happiness, and fulfillment. We need to recognize these obstructions, recalibrate our lives, and restore equilibrium. Consider the journey a homecoming to the natural default point, a center from which we can re-engage the genuine rewards of living the full measure of our essential humanity. Now let’s take a look at the 10 Habits of Highly Successful Hunter-Gatherers. Think of them as a set of tools that will give you an evolutionary perspective and help you navigate the rest of this book.

TAKE RESPONSIBILITY

TAKE RESPONSIBILITYPerhaps the most powerful and uniquely human trait of our hunter-gatherer ancestors was their full acknowledgment of life’s realities as well as its cruelties. If you can tap into this one part of the Primal Connection fully, every other piece of information will seem to fall into place effortlessly. I assure you, it isn’t an easy fix, as we have been socialized to blame our predicament on anything and everyone but ourselves, but it is essential to achieving peace and balance.

Nowadays we have the luxury of wallowing in despair, self-pity, self-judgment, or doubt. Not so in Grok’s day. Life was harsh, unforgiving, and unrelenting in throwing challenges at our hunter-gatherer ancestors. Can you imagine them moping around with their heads hung low, judging themselves as failures when they didn’t catch the beast they had been tracking, or when they discovered that the water source they’d finally found was tainted? Highly unlikely! Maybe disappointed, but to the hunter-gatherer, a victim mindset would have been a sure recipe for death. As Art DeVany, author of The New Evolution Diet, is fond of saying, to the hunter-gatherer, there is no failure— only feedback. Indeed, survival required that our ancestors regroup and forge ahead to the next challenge when they faced unfavorable circumstances. Sure, our ancestors did things with a purpose (a goal), but had the outcome not been to their advantage, they likely accepted it and moved on, trying again later or devising an alternate plan.

This is what owning your life, owning your problems, and owning the outcome looked like ten thousand years ago. This is what taking responsibility for your life—everything that has ever happened to you, and everything that ever will happen to you—should look like today. Picture the modern human wearing a suit instead of animal skins and hunting for a job instead of a beast. Same genetic recipe and proclivities, simply a different set of circumstances.

Taking responsibility for your life doesn’t mean that you have to lay blame on yourself. What I’m talking about here is choice, and how you choose to respond to any given situation. It could be that you had a spate of bad luck, were born into less-than-ideal circumstances, had abusive parents, fell in with the wrong crowd, or just got bad information. It means that you don’t make excuses, and you don’t necessarily place blame on others for your current sour situation. Hey, it could technically be someone else’s “fault,” but blaming allows you to languish in the presumed comfort of bad habits. It allows you to stew in self-pity, to accept inertia for the sake of ongoing bitterness. Yet, blame always betrays you in the end. Whatever excuses you tell yourself day after day, the sense of loss—of being locked outside of your own life—is still there. It’s a grief that leaves you hollowed out and estranged. Responsibility is your acceptance of the situation, your acknowledgment that however it happened, you are the only one who can make the choices to get yourself out.

Unlike other animals, humans evolved an ability to respond emotionally to situations, rather than simply to react rationally. Reaction is the province of the fight-or-flight system that predates humans by hundreds of millions of years. Reaction is wired into our reptilian brains as a survival mechanism. It doesn’t require much thought; it’s automatic. On the other hand, the brain’s neocortex (evolved over millions of years with aid of our high-fat diet) can override the knee-jerk, fight-or-flight reactions typical of most other species and run quickly through various what-if scenarios and plot alternative strategies for myriad life-threatening encounters.

Nevertheless, despite our ability to think our way out of a tight spot, our fight-or-flight tendencies are deeply rooted . The skill to separate, or appropriately integrate, our two modes of thinking (react blindly or respond intelligently—we call it “response ability”) can make a huge difference in your own life, whether it has to do with finances, health, relationships, or real survival situations.

Like our ancestors, every morning we wake up to face a day of uncertainty. Recognize that bad things happen all the time. But how we deal with those things is ours and ours alone. If you get rear-ended at a stoplight, it may not be your fault, but the choices you made put you in that place, on that day, and at that time. Acknowledge and accept the problem, and consider your available choices—including whether or not you will allow this to ruin your day or week.

If you are addicted to pain pills, in an unhappy marriage, struggling with your weight, or one of the millions on their way to type 2 diabetes, be brutally honest with yourself right now, and ask what behaviors, actions, and decisions you made to be in the situation you are in currently. If there is even the remotest hint of excuse or blame, you are not in control of your own destiny. You are essentially allowing life to happen, like a boat lost at sea without a captain.

In finally giving up the blame game, we make peace with the complexity and difficulty of life. We shake off the last of our excuses, and let go of the martyr role. We become the essence of the hunter-gatherer. True, life isn’t always fair. We don’t get to choose every circumstance. We don’t get to control the people around us. Likewise, we don’t get all the time in the world to wait for the ideal circumstances to come around. Life, as we all eventually come to understand (hopefully before it’s too late), will never be perfect. There will always be obstacles, annoyances, and limitations to contend with on our paths. Regardless of what your life looks like next to someone else’s, yours is still the one you go home with at the end of the day. Yours is the one you get to live—for all its possibility as well as challenge. The question is: what will you make of it today?

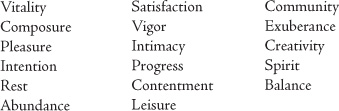

Think about your own life right now. How would you describe your health? Your overall sense of wellbeing? What have been your challenges? What have been the high points of your life? Where do you feel limited? How do you feel supported? What gives you strength and joy? What do you long for? The point here is to understand the story and intentions that you bring to your life’s journey. Look at the following list of concepts and relate them to your life right now. Acknowledge the first words that come to mind as you read each.

Now think about these same concepts again, only this time in relation to your desired life. Ask yourself this: what is standing in the way of achieving this life? What are the obstacles that block your path? Specific circumstances? Lack of energy? Lack of time? Lack of direction? Stress? Illness? Anger? Emptiness? Misguided priorities? Entrenched habit? Now evaluate your choices. Begin steering your life with those that best align with your desired destination.

Set up a WTF Fund. Stuff happens in life, and sometimes it costs money to fix. No reason to get upset. Create a separate budgetary item made up of spare change, $20 a week, or a small percentage of your paycheck. When a WTF moment happens—a broken window, overpaying for a good or service, or seeing a family member buy something you deem as irresponsible or excessive—don’t be a victim. Tap into your WTF Fund and fugetaboutit!

BE SELFISH

BE SELFISHWhat kind of entity is it that survives, or does not survive, as a consequence of natural selection? This is the question Richard Dawkins asked as he penned his seminal work The Selfish Gene. He later lamented that he should have titled the book The Immortal Gene or even The Altruistic Vehicle, because in reality his book detailed how altruism figured greatly in the evolution of our species. In order to survive, we fed and protected our kin who shared copies of our genetic material. We evolved depending on and cooperating with the small group to which we were attached, always recognizing that survival is nearly impossible without the support of others. We indeed had serious motivation to get along, to pitch in, to be, well, altruistic. Yet the human race could not have survived without a degree of selfishness. After all, the caveman ethos is not that of a martyr.

Being selfish does not mean valuing yourself above all others. It means being as generous with yourself as you are with others. If you believe that all people should be protected, nurtured, loved, and filled with joy, then recognize that you are a person, too, deserving of all those things as well. No one is better equipped to provide that to you than yourself. For example, consider the go-to person at the office, the one everyone can count on to put in the extra hours and get the work done. He has a hard time saying no, and maybe a part of him secretly enjoys carrying the extra burden. But under the crush of trying to please and taking on too much, it is often at the expense of his physical, emotional, and mental health. Ultimately, unless he pays attention to this, he will burn out. We see intimate relationships undergo a similar fate when one lover assigns a disproportionate amount of time and energy to the other. The latter eventually feels stifled while the former feels resentful. How might these scenarios play out differently if the selfless became a little more considerate of their own wellbeing—negotiating for more time on a project or additional help, or investing time and energy in self-improvement rather than slavishly doting on another who may or may not appreciate it?

Essentially, it all boils to down how you determine your decisions. Start by consulting yourself first. How do you feel about the issue? How does it supply your needs or infringe upon them? What do you want? Once you have a baseline of your own position, then and only then do you expand the question to that of anyone else involved, or affected. You may opt to consider others over yourself in the end, but you will have done so with a clear and compelling reason to acquiesce to other purposes. You will have made a choice, and choices are what it’s all about.

Of course, parenting, by definition, is a selfless endeavor in which we choose to participate. We enter the parenting game knowing this, and the rewards we reap in return are immeasurable. But when self-sacrifice is taken to the extreme, when you are beginning to indulge the wants of your children before your own basic needs, it may be time to pull back and re-evaluate. I’m talking about running yourself ragged working a second job so that you can earn the money to buy your children new video games and designer clothes, yet you haven’t any spare time to spend with your children, let alone get enough sleep. I’m talking about not setting boundaries, the inability to say no, and doing things for your children that they could do themselves such as cleaning their rooms instead of assigning chores. At the end of the day, the question then becomes what sort of role model do you want to be for your children to emulate once they grow up and become parents themselves?

Think of it this way: the more you sacrifice your own health, happiness, and sanity, the less you have to give. Conversely, when you have a healthy relationship with yourself, the happier and better off you are, and therefore the more valuable your gifts to others will become. You become a better lover, a better parent, a better volunteer, a better employee, a better member of society. Simply put, we have to help ourselves before we can help others. We are reminded of this simple principle every time we board a plane and are instructed to put on our own oxygen mask first before assisting our family members in the event of an emergency. The truth is, we simply cannot be altruistic without being selfish first. Just don’t go overboard and sacrifice other people’s welfare in pursuit of your own.

Treat yourself to some guilt-free me-time. Carve out some time and spend a day at the spa, take a drive up the coast, relish a lazy day on the couch reading a novel, enjoy a long soak in the tub, or play golf in the middle of the week.

Find an old picture of yourself, one of you as a child. What would you like to do for that child? What does that child need that you can give him or her now? If it’s a trip to the zoo, go. If it’s more complicated (and whose life isn’t?) list out the challenges, and write about what thoughts or actions you would need to better nurture your inner child.

Have kinder communications with yourself. Instead of negative self-talk, try saying positive words like joy, love, life, happy, strong, beautiful, tranquility. Affirmations are wonderfully healing, too, especially those starting with the words, I am. I am healthy. I am happy. I am positive.

BUILD A TRIBE

BUILD A TRIBEA strong social circle for our hunter-gatherer forebears was a given. As we’ve just learned, in the harsh circumstances of their time, it would’ve been near impossible to scratch out a life alone. Instead, they lived within the security of a band community—a kinship group of approximately twenty-five to seventy people. Some within the group were related. Others were not. Participation within the group was more than simple transaction or familial affiliation. Kinship was created through a sense of mutuality—forged in action. The bond was born out of continual, concrete participation in the group—in engaging with the hunting and foraging that would feed the community; in protecting the group from predators or in the occasional skirmish with another band; in aiding the group with building shelters, creating vessels and weapons, or caring for children; in sharing celebrations; and in receiving the group’s aid and support.

What a contrast to think that these days people can go through their adult lives with few, if any, intimate connections. It isn’t that we’ve outgrown the need for kinship. We still, after all, have the same genes that promoted social connection for the sake of survival hundreds of thousands of years ago. What’s changed is our culture. We no longer necessarily stay in our hometowns or even home countries. We may live thousands of miles away from our families of origin and childhood friends. In fact, we may make several geographical relocations in our lives for school, work, marriage, or whim. Even if we stay in one place for a long stretch, we get busy, life gets complicated, and we lose touch. As a result, many of us end up feeling unattached, socially adrift.

Wherever and at whatever time in your life you find yourself now, it’s imperative to build a tribe. The irony of doing so in this day and age, of course, is we live every day in proximity to thousands of people as opposed to the few and far between as our ancestors did. We have hundreds of social media connections but few real relationships. The truth is, exposure doesn’t fill our social wells. It’s about solid, mutually supportive relationships. A tribe here represents people with whom you feel closest, the people you feel know you the best and have seen you through life transitions or meaningful events. Likewise, you’ve done the same for them. You have a history, and likely a lot of stories that can keep you reminiscing deep into the night. These relationships include your life partner, your kids, your family of origin, and maybe closer members of your extended family. But it’s also—and for some people more so—intimate friends. These are the friends you can drop by and visit unannounced. They’re the ones you can call—and call upon—at all hours.

Bottom line, if you don’t have a family, make one. If you don’t have a core group, build one. Don’t tell yourself you missed the boat on this one. Don’t tell yourself you’re too busy. This is too important.

Sure, making friends as an adult isn’t the casual, happenstance arrangement that it is when you’re a kid or even when you’re in college, but it’s just as vital and rewarding. Sociology professor Rebecca G. Adams from the University of Carolina at Greensboro explains the three keys that are essential to form intimate friendships: “proximity; repeated, unplanned interactions; and a setting that encourages people to let their guard down and confide in each other.”1Ask yourself what kind of people you want to be surrounded by, and ask yourself what you have to offer in return. Go to the places where they go. Introduce yourself. Participate. Initiate connections.

This said, bring a genuine interest in the people you encounter. Ask questions and make eye contact. And don’t limit yourself to finding your personal doppelgänger. Conversations with people who hold a different point of view from yours can make for lively conversation. Prioritize key principles, but bring an otherwise open attitude. Offer trustworthiness and respect as well as pragmatism. If they don’t return the same level of interest, move on rather than waste your time and emotional investment. Along that vein, think quality over quantity. Cultivate the relationships you think you have the time, motivation, and energy to maintain. A few genuine friendships are more rewarding than a hundred acquaintances.

Foster relationships within the connections you already have. There’s no need to start from scratch. Think of people you already know but with whom you never had the chance to develop something more involved, or reconnect with old acquaintances through an alumni group. Put yourself out there and extend a personal invitation.

Lead with your personal interests. Take a class. Join a sports league, running club, book group, or professional organization. Try a Meetup group in your area. You won’t only be meeting like-minded people, but you’ll have the ongoing chance to build a relationship over time. And—if nothing else—you’ll enjoy the activity just for its own sake.

Be an organizer. Take the bull by the horns and throw a party. Coordinate a volunteer team at work. Start a fantasy sports league or mothers’ group. You’d be surprised how many people want to connect as much as you do but are just as intimidated by getting the ball rolling.

Bring your best to the relationship and look for the same. You’re looking for people who can be positive, enriching, supportive friends. Offer that in return. Even long-term friendships can go south if one person constantly unloads or if the routine becomes too ho-hum. Renew the energy and interest in your friendships—new and old.

BE PRESENT

BE PRESENTFor our hunter-gatherer ancestors, life was an exercise in hypervigilance. Life in the wild allowed for very little leeway in awareness. Picture a hunter-gatherer examining subtle patterns of broken twigs and bent grasses as he tracked prey. At turns, he would stop to smell the breeze and seek out whiffs of scat. He lived life in the imperative of the now. Though he and his kind lived lives consisting of large amounts of downtime, they were rarely afforded the luxury of “checking out” mentally, lest they become the prey instead of the predator. It wasn’t just the business of hunting—or avoiding being hunted—either. Attentiveness mattered to all of life and livelihood then. Our hunter-gatherer forebears deciphered sensory cues that signaled migratory patterns, edible plants, water sources, navigation cues, impending weather, and the occasional outsiders’ presence. Distraction could mean missing essential clues that would make the difference between a healthy meal and a deadly one, a route to resource-rich land and a path to nowhere. Being present meant not getting lost on the way home. It meant staying alive.

By contrast, we moderns are used to walking through life preoccupied. You see it everywhere—people absorbed in their phones as they walk down the street, or as they stave off their young children’s efforts for attention. There’s always some harried businessman rushing through pedestrian traffic muttering a frustrated obscenity under his breath.

Whether it’s technology or mental chatter, we’re chronically lost in distractions of our own making. We justify it as multitasking, except each task suffers with every additional undertaking. It’s about letting constant distraction hijack the full experience of life. How often are we preoccupied by everything but the people, places, and possibilities right in front of us? Our enslavement to diversion suggests a strangling self-absorption. In our ancestors’ day, it would’ve been our fatal undoing. Today, it’s “merely” a psychological burden we continually impose on our psyches. We’re locked inside ourselves, more often than not, disconnected from the world and people around us.

In terms of business, our diverted attentions sacrifice efficiency and creativity. As research demonstrates, multitasking doesn’t save us time and brainpower. Our learning capacity actually diminishes when we multitask, taxing our short-term memory unnecessarily. Furthermore, we miss out on the creative and emotional benefits of flow, that state of mind in which self-consciousness slips away in a larger, engrossing challenge. In these hyperfocused moments, we experience the rewards of emotional release as well as creative productivity, much the way our ancestors did during their daily endeavors.

When it comes to our relationships, distraction means we forgo the intimacy that builds genuine connection. Too often we skate over the surface of relating, always caught in one more thought, one more email, one more list. We’ll focus after just this “one last thing,” we say, but somehow there’s always another task, message, or diversion waiting. Your kids and partners, friends and relatives all sense when you’re distracted. Imagine giving them your full sensory, intellectual, and emotional presence. Can you remember what that feels like? Can they? Make the commitment to be fully present for them. Let yourself be taken in by their smiles, their conversation, their closeness. Being in the moment with someone means giving that person your whole self as well as your full attention. Your loved ones deserve nothing less.

Observe your loved ones. Watch your children play. Listen to their voices and laughter. Look them in the eyes when you speak with them. Absorb the subtle changes in their growing selves. Embed in your mind the memory of your partner’s laughter or an aging parent’s mannerisms. The people you love change every day. Don’t miss it.

Identify twenty things you haven’t noticed before. Next time you take a walk through your neighborhood or a familiar natural environment, act like a hunter-gatherer and catalogue your surroundings. Make it a habit each time you venture out for a walk.

Take up a meditative practice. Research demonstrates that meditation, yoga, Tai Chi, and visualization improves attention skills. They can also help quiet the “monkey mind,” a yoga term for that unrelenting, manic, mental busyness that won’t let you slow down and empty your thoughts.

Incorporate mindfulness check-ins throughout your day. Whether or not you meditate each day, resolve to infuse your life with a more mindful presence. Regular check-ins throughout the day—at breakfast with your spouse, on your lunch hour walk, during quality time with your kids—help you improve mindfulness as a way of living.

BE CURIOUS

BE CURIOUSAs children we have an eager, spastic attraction to the new, the mysterious, the out of reach. From that infinite string of “why” questions to the unrelenting energy for the day’s adventures, curiosity is a near constant impulse. Life is to be probed, painted, taken apart, reconstructed, and fit into a fantasy tale with action figures. We tend to interpret these memories as the nostalgic stuff of childhood—adventures in naïveté in the early throes of encountering our small worlds. Ah, but it is so much more. Engaging our curiosity is a universal, adaptive human impulse—one that should be encouraged throughout life.

Humans didn’t evolve a particularly imposing size, defensive shell, or threatening physical features. We developed wits instead. In a dicey survival situation, our ancestors depended on knowledge and creative ability to manipulate their physical environments or predatory opponents. They learned to use all manner of natural materials to create shelter, devise medicinal treatment, and incorporate nutritional fortification, through observation and imagination.

We moderns are products of our ancestors’ genetically programmed curiosity. When we think of the older people we know who seem the most youthful and fascinating, they’re undoubtedly the ones who never stopped exploring, discovering, learning. They are always reading several books. They travel. They start their own business or adopt a second vocation late in life. They love sampling new recipes or visiting the latest restaurants in town. They attend lectures and cultural events. They are always building something. For them, life is an adventure, no matter how many years they have left to explore. They remind us that there is always something fortifying to the pursuit, the question, the revelation.

Life is an open invitation to discover. It’s a question of how we engage with our world, how we apprehend and encounter the stimuli around us. Do we go through life with senses turned off, suspended in the thoughts of the next task, or do we bring presence, openness, and curiosity? It’s worth asking, how often do you seek out novelty of any kind? Do you feel— and follow—curiosity? When was the last time you felt like you really learned something or have grown from something? We have the potential to challenge our limits and learning throughout the full span of our lives—if we choose to.

Be a lifelong learner and commit to a continual education. Read widely and deeply. Watch documentaries. Take classes. Attend seminars. Volunteer. Travel when time and money allow. One educational travel resource to check out is RoadScholar.org. For brain games that will enhance your memory, attention, and creativity look into Lumosity.com.

Connect with others who want to learn and question. There’s nothing as inspiring as a long, rousing conversation late into the night about the deep subjects of life. Have people in your life (ideally not of the same opinions) with whom you can share this experience.

Push your personal boundaries. Try new activities on a monthly if not weekly basis. Try a cultural cuisine you’ve never eaten. Visit a new museum. Take in a play, concert, or sporting event that’s unlike anything you’ve attended before.

Explore new hobbies. Don’t just read about new subjects, do them. Take up woodworking, weaving, clock building, pottery, gardening, or carpentry. Learn how to sew your own clothes or make your own masterpiece recipes. Fix your own car or build your own backyard shed. There’s little to nothing you can’t learn if you commit yourself to the endeavor.

TRUST YOUR GUT

TRUST YOUR GUTAn extraordinary confluence of sensory abilities helped our ancestors survive a complex, dangerous, and unpredictable world. Acute hearing warned them of approaching predators. A sensitive sense of smell allowed them to anticipate weather and track prey. Sharp and discerning sight helped them differentiate between edible and inedible plants, and navigate both land and open water. Although predominantly a blend of intense sensory awareness, this perceptiveness also incorporated intuitive discernment, a rapid-reasoning neural network that was by itself critically adaptive.

We observe how animals act upon what we call intuition. They seek shelter from storms and natural disasters before people pick up any detectable signs. It’s likely that humans at one time had all the same intuitive abilities as our animal cohorts. The fact is, even traditional hunter-gatherer groups today show perception so keen that it can smack of mysticism. Experts are somewhat split on whether we still retain the full measure of these capacities. However, research involving traditional societies and laboratory observation suggests that we still possess key intuitive abilities—and that they play a crucial role in our everyday existence.2

We feel intuition viscerally because it’s very much a bodily perception. It’s a nonverbal, untraceable insight that is actually assembled from perceptual cues, emotional associations, past physical experience, and genetically programmed instincts—often within a split-second. In that way, intuition can seem like an animalistic force, what anthropologist Robert Wolff calls an ancient way of knowing.3 Although decidedly primal, intuition is hardly an obsolete mode of processing. Even in the twenty-first century, we remain creatures of “dual processing,” the intuitive and the intellectual. The key is giving each their proper due.

Experts have long searched for the “seat” of intuition. It’s more likely to be part of a complex network than a lone site in our physiological makeup. From a sensory angle, we respond to visual input too fleeting to consciously register. We pick up on everything from subtle facial expressions to hormonal secretions in sizing up or just living with another person. In a fraction of a second, information gets routed through a map of neurological shortcuts—within and outside the actual brain. Before your higher-order thinking can even begin to kick in, the “second brain” of your enteric nervous system (yes, truly your gut) is already giving you feedback. That bad feeling in the pit of your stomach is a legitimate message created in the larger network of neurohormonal production and communication.

We humans have evolved amazing abilities of higher cognition, but we pay a price for that as well. Although our intuitive powers have likely diminished compared to that of other mammals, we—much to our detriment—tend to discount our intuition wholesale. How many times have you made a decision in life and immediately descended into a cascade of second-guessing because your neocortex was late in the game with its logical what-if scenarios? Maybe you’ve experienced changing your mind based on this rationalist rebellion only to later regret the switch after you see the undesirable result. If only I’d gone with my gut, you think.

Research confirms that we often make better decisions—and are more satisfied with our choices—when we rely on intuition rather than reasoning.4 For instance, we tend to think our conscious mind makes fairer judgments, but research suggests we’re perhaps more beholden to biases in the decisions we make with conscious deliberation. And we think less creatively when we rely on conscious thought. The subconscious mind, not surprisingly, is better than the conscious one at thinking “out of the box.” In a series of studies, the best solutions and choices were made by those who were given a question and then distracted for a short period of time, rather than given time to consciously reflect on the decision, or asked to answer right away.5 Anyone frustrated by a problem who has found an answer after getting up and walking around the block has experienced this phenomenon. Absolutely, conscious deliberation allows us to work collectively, engage willpower, and shift habits. Your higher brain, for example, is much more likely to resist that bag of M&M’s next to you at the checkout. Nonetheless, there’s more truth and innovation to be had in the full integration of your cognitive, human self. You’ll find genuine guidance when you trust your gut.

“Traditional hunter-gatherer groups today show perception so keen that it can smack of mysticism.”

Get in touch with your own decision-making center. Recognize the conscious “voices” in your decision making—the psychological baggage of bad experiences and misguided authority figures. Clear out the emotional clutter of the past that keeps creeping into your life choices.

When you need to make a decision or approach a problem creatively, stop mulling and step away from the issue. Give yourself a break with some other activity and let your subconscious mind take a stab at it. Head out for a run, take the night to socialize, or try one of the above ideas to mute the rationalist volume and give your subconscious some air space.

PICK YOUR BATTLES

PICK YOUR BATTLESFor our hunter-gatherer forebears, life was an exercise in cost-benefit analysis. Did it pay to migrate during a certain season? Was it worth the risk to try hunting bigger predators? How did the time collecting and preparing a certain plant for eating stack up against the taste and satiation? Unless there was something substantial to be gained that made the endeavor worth the extra effort, danger, or conflict, our ancestors favored choices that conserved their energy, minimized risk, and maintained band equilibrium.

Despite our lives of unprecedented choice and ease, we’d still do well to apply the same principle: lead with the priorities. There are the practical choices. By way of illustration, is it worth paying someone twice the amount to drywall the basement when you could probably do a decent job yourself with a bigger time investment? It’s a call you base on how much or how little free time you have versus spare cash.

Beyond these literal cost-benefit equations, however, exist the more emotional and social considerations you make every day. How do you invest your time and energy in your relationships? How much of your engagement goes to doling out orders and criticism—however “constructive” you believe them to be? What else could—or should—you be seeing and appreciating in others if you let more of the negatives slide?

In a situation that would normally ruffle your feathers, ask yourself what you stand to gain by fighting the battle. Is this battle substantial or essential? Does the situation even require your response? To every action, there’s an opposite reaction. Consider what and who you will be upsetting if you go down this road. Perhaps there could be ramifications. Think about what you may bring down on yourself with this battle, maybe losing a client, alienating your partner, or disappointing your children.

Choosing an unnecessary battle won’t unravel your life in one bout. However, if you can’t back away from constant criticism or refuse to let go of anything, you can gradually wear away and close off the intimacy and good will of your relationships—from business connections to intimate partnerships. Moreover, continually engaging in cynicism has a tendency to just plain wear you down.

At a certain point, constant battles suggest an inability to compromise. It implies an inability to respect the full humanity of other people and the unpredictable nature of life itself. A will to control wouldn’t have been tolerated in the autonomy-minded hunter-gatherer culture. Today, you might not literally be voted off the island as you perhaps would’ve been then, but you’ll eventually make yourself irrelevant and unwelcome.

The larger lesson runs deeper than simply cutting back on negativity, however. It obliges us to think about how we approach our relationships and how our own sense of self enriches or impairs our connections. Maybe you haven’t identified what the core priorities are in your life yet. That’s critical personal work. The longer you put it off, the more conflict and lost opportunity you’ll undoubtedly bring upon yourself. There’s no single or fixed answer, but it’s a question that engages your expectations of life and other people, as well as your own self-knowledge and healthy sense of humility. People in old age often share how the end of life brings perspective to what really matters. Impending loss is perhaps the ultimate lens on such things. Nonetheless, our experience and reflection throughout our lives teach us, if we let them.

Finally, we can choose our battles wisely when it comes to our own self-development. Selecting your most valued goals and releasing others isn’t an exercise in defeat. Over the years, you inevitably gain a sense of proportion, appreciating the depths of each experience and commitment.

Identify your priorities. Too many people hit their later years and think, “I’ve fought all the wrong battles. Now look where I am.” Identify your values, create your priorities, and make those the dynamic template for how you live your life and love the people close to you.

Keep a daily battle log. Divide your log into sections devoted to each of your daily relationships. These might include your partner, child, boss, best friend, etc. When you pick a battle by making a demand, setting a condition, or offering a criticism, write it down. Note what it was and how you presented it. Examine the results at the end of each day. Push yourself by limiting yourself to one (yes, one) battle a day. If you chose to make an issue of the toothpaste cap off the toothpaste, you’ve filled your quota for the day, and you’re done no matter what other significant issues come up. Use the exercise to learn to lead with your priorities.

Cultivate a new dimension. How much of your happiness is controlled by other people? No one is happy all the time, but do you have a foundation that centers you and offers you emotional stability, no matter what your surrounding circumstances? If you keep yourself on secure emotional ground, you’re better able to lead with your ultimate priorities and to be in richer, more genuine relationships with other people.

GET OVER IT

GET OVER ITThe hunter-gatherer society certainly saw its measure of conflict and revenge, but it was also the breeding ground for our capacity to forgive. Michael E. McCullough, author of Beyond Revenge: The Evolution of the Forgiveness Instinct, explains that the ability to forgive is as much a result of natural selection as the impulse for revenge. It’s a practice that’s been observed in nearly every human society and in other animals, including chimpanzees, which offer soothing sounds and touch following antagonistic confrontations. Forgiveness, McCullough suggests, likely evolved as a means of social cooperation: “By forgiving and repairing relationships, our ancestors were in a better position to glean the benefits of cooperation between group members—which, in turn, increased their evolutionary fitness.”6

The fact is, a band member who wouldn’t give up a grudge would’ve been a serious drag on the rest of the group. If he couldn’t learn to let it go, he probably would’ve been out of the picture before too long. There just wasn’t room for festering negative emotions that eroded the community. Band life was flexible, and individuals occasionally left (or were forced to leave) because of social conflict. However, being shunned or choosing to leave at an inopportune time in the season left a person extremely vulnerable. The risk just wasn’t worth the emotional indulgence. Put simply, a thick skin would’ve been beneficial to survival.

“The hunter-gatherer society certainly saw its measure of conflict and revenge, but it was also the breeding ground for our capacity to forgive.”

Without this traditional imperative to let it go, we moderns too often indulge in wallowing—to our own detriment. How many people walk around living “half-lives” because so much of themselves is entangled in the bramble of past hurts, offenses, and travails? How many years will they allow themselves to be stuck there? What will they miss out on in the meantime?

Forgiveness isn’t just about the other person’s wellbeing. It’s ultimately about your own. You’re cutting the present loose from the past. You’re putting yourself in charge of your own emotional health instead of letting someone else dictate it each day of your life. Research shows that people who forgive are more satisfied with life, and experience fewer feelings of emotional distress. Likewise, if you’re the one who made a mistake and are still suffering the emotional toll, accept that it’s time to move forward. Take responsibility, choose to live in integrity with yourself and others. Every day you let another person—or past mistake— control your wellbeing is a day you miss living fully.

In addition to releasing the significant resentments from your past, learn to let go of the smaller daily conflicts that build up with the people in your life—your significant other, children, co-workers, and friends. Imagine the individual peace and relationship potential that you might gain with a shift in your emotions.

Learn to recognize negative self-chatter. When you start to go down the emotional road of replaying negative experiences, change the recording. We all do it at some point—mulling every nuance of a past failure, recalling every wrinkle of negative interactions. Cultivate the discipline to stop yourself mid-thought and diffuse the angry, fight-or-flight hormonal cascade before it overtakes you. Identify the physical feelings and mental associations that set it all in motion. Consciously stop the thought and step back from the precipice. Relax and redirect.

Use ritual to create emotional closure. There’s an old New Year’s tradition (attributed to a number of countries) of opening the front door at midnight to sweep out the old and let in the new. It’s a meaningful metaphor in choosing forgiveness. Some people write down their thoughts about the past and burn them to make manifest the letting go of the old—disappointments, regrets, grief, and even joys. The idea here is to create the mental space that allows you to be fully present in the now, in each new moment—to not be burdened by past defeats or grudges or relying on previous successes. Resolve each day to open up that door—to accept the past for all its good and bad and then let it go, to meet the new day with determination, optimism, and no excuses.

SHARPEN YOUR SPEAR

SHARPEN YOUR SPEARAnthropologically, Homo sapiens sapiens (i.e., modern humans) ultimately prevailed over the Homo sapiens neanderthalensis in the theater of evolution. Why? Despite all the badmouthing, Neanderthals weren’t the dim, slow creatures they’re often accused of having been. Anthropological evidence suggests they used hunting implements, made clothing, built shelters, and buried their dead. If Neanderthals had so much in common with Homo sapiens sapiens, what made the fatal difference? What did Homo sapiens sapiens have that they didn’t? The answer: better tools, better skills.7

The two groups hashed out their existence (and evolutionary competition) in a descending Ice Age. The group that adapted the best won out, and the rest is history. Homo sapiens sapiens are thought to have been better foragers. They’re known to have had the pivotal advantage of projectile weapons for hunting. Many experts believe they benefited from developing a more complex language ability. Despite having survived for more than 150,000 years in the relatively harsh climate of Europe, the Neanderthals succumbed when conditions took a turn for the worse. Homo sap sap, however, had what it took to make it through.

“Homo sapiens sapiens (i.e. modern humans) ultimately prevailed over the Homo sapiens neanderthalensis in the theater of evolution. Why?”

Fast-forward to today, and we in the twenty-first century face a similar challenge of trying to make a living in ever-changing conditions. We aren’t working with the long scope of evolution in our personal pursuits, but the general lesson holds: to get what we want, we must fashion a better spear. This can mean pushing yourself to new dimensions in your career. It can mean creating a job situation that allows you to live your values and offers you more flexibility. It can mean cultivating a sense of vocation outside of your specific profession. Ultimately, sharpening your spear is about developing yourself in satisfying, diversified ways that will help you experience success, however you conceive of it.

For most of us, a career easily consumes most of our time. We want that investment to offer something substantial and enriching to our lives. So, at the very least, we can bring a positive, primal attitude to subsistence. Instead of thinking of work as something you have to do, think of it as something you get to do. And that means you get to have your basic needs met. You get to put dinner on the table for ourselves and our families. That would’ve been enough for our hunter-gatherer ancestors to celebrate. When we lose sight of the basic value of our effort, we forget to experience the joy.

Many times—understandably—we want more from that investment. We’re looking for a means of self-actualization. We’re looking for intellectual challenge, social engagement, creative potential. Too often people go after the profession they think they’re supposed to want—because of the paycheck, prestige, or apparent security. Others feel locked into a career because of age. This job is all they’ve ever done, and it must be too late to take on new ventures. Nothing could be further from the truth.

In traditional societies, men and women often take on new roles with age. Decide to own the self-knowledge that comes with age, and have the courage to invent a new and better path for yourself. Whatever stage in the game you’re at, if you can choose a career that aligns with your passion, your professional path will offer fulfillment as well as prosperity. Developing a successful career, like creating a more complex projectile, takes time and dedication. Investing in a passion is a lot more motivating—and rewarding.

Either way, develop yourself broadly. “Specialization,” as sci-fi writer Robert A. Heinlein once said, “is for insects.” You’re more than a single role, a discrete skill, a particular job. Our ancestors, by necessity, were Jacks and Janes of many trades. In a small band, it was too risky to turn over essential functions to an individual who may leave at the end of a migratory season (or be killed by a predator). It’s a privilege this day and age to decide what is and is not worth your time, but there’s something to be said for being well-rounded. Genius, for example, doesn’t stem from the tunnel vision of specialization but from the innovative visualization of creative, unexpected connections. On more modest terms, simply having a whole host of skills can expand not only your self-sufficiency, but your sense of personal identity, competence, and resiliency.

Take a class or attend a conference. Maybe it’s a new dimension of your current profession or a new path entirely. Learn more about the scope of the field and the variety of positions in it.

Volunteer or take a side job. If your current job isn’t your personal passion, try something on the side that feeds your interest.

Fill your free time wisely. Choose activities and social connections that enrich and expand your life. Read. Travel. Develop yourself through a hobby.

BE AFFLUENT

BE AFFLUENTMost of what we’re taught about our hunter-gatherer forebearers suggests their lives were nothing but animalistic want and abject misery. Imagine, however, an existence raw yet less brutish than we’ve been taught, one that included periods of great abundance. This was the radical notion set forth by anthropologist Marshall Sahlins in 1966, when he convincingly argued that our hunter-gatherer ancestors were the original affluent society.

Sahlin’s anthropological analyses suggest we can estimate hunter-gatherers’ daily foraging and food preparation time between two and six hours a day. Translation: vast amounts of leisure time!

So, how did they fill a typical day? Barring some apparent threat or dramatic weather incident, they’d likely take their time in the morning. What was there to rush to anyway? There might be talk of the previous day’s activities or plans for an impending hunt. Some might draw water from a nearby stream. Children would play. Babies and toddlers would nurse. Those who were hungry right away could munch on remnants of the prior day’s gatherings or lightly forage for a morning meal. A successful hunting day was enough to warrant an evening feast, followed later with bringing out drums, flutes, dried pods, and other instruments. They would sing. Many would dance. Other nights might bring well-known and welcome stories around the intimacy of a fire circle. Beyond the circle there would be little to watch on most nights but the stars and the dim silhouette of a darkening landscape, the nearby sound of the wind in the grasses and, in the distance, calls of animals.

“We can estimate hunter-gatherers’ daily foraging and food preparation time between two and six hours a day. Translation: vast amounts of leisure time!”

Let me make it perfectly clear now that I’m not advocating that you quit your job, disavow your worldly possessions, join a commune, and walk around barefoot in a robe all day. (Well, the barefoot part would be OK.) I support working hard, competing in the free market, and contributing to the economy by producing and consuming goods and services to make for a better life for yourself and those around you. While there is opportunity for lively philosophical debate about the inequitable distribution of wealth, abuse of human and natural resources, and other flaws inherent with the modern global economy, I prefer that we focus here on broadening your perspective of wealth to include good health, creative freedom, job satisfaction, and deeply meaningful relationships with family and friends. Above all, I’d like to emphasize quality time.

At birth, we are bestowed with the gift of life, which, when you boil it all down, amounts to large a block of time. How we choose to spend this valuable gift is ours and ours alone. In our youth, we have little concept of time, perhaps as it should be, filling it with play, curiosity, and discovery. Yet as adults, when we’re not logging in hours building a career, we fill it with undesired social obligations, full itineraries, and endless chores—tethered to status and possessions. Shouldn’t our time be more enjoyable, more leisurely?

Sadly, too many ask themselves this question just as their time begins to markedly shrink, leaving them wondering if their days on this planet could have been better spent. It is only then they begin to appreciate the simplest of pleasures, those very things that had always been there but had typically been taken for granted.

When it comes to enriching experiences—quality time—what can our ancestors’ example teach us? We sometimes imagine that if we could just “manage” our time and organize our lives better that we’ll be happier and more relaxed. Maybe we need less to manage in the first place. (That goes double for the kids.) Do we truly need more impressive weekend plans? Maybe we should just spend more time sprawled out in the grass laughing with the kids or curling up with our partner. A Sunday afternoon nap is an underappreciated indulgence. How about lounging at the local beach or park—or enjoying a glass of wine sitting in the kiddie pool after the kids have gone to bed? These are simple but seemingly scarce luxuries these days. Try including more frequent pleasures in your life— ideally, fifty percent of your waking time. Yes, I know. That’s a lot considering the typical forty-hour workweek. But there are ways, even during your rush-hour morning commutes, to grasp additional leisure time. Let’s explore.

Gratitude, with a capital G. The word should resonate as holy (which has the same root as healthy, and means whole), for without it, boredom prevails. With it, you acknowledge and appreciate life’s gifts. This embodiment extends beyond your attitude to become an actual personality trait, a stress management tool, and an overall way of life. You live in gratitude because you are here today— appreciative of the lessons and journey of your past, however imperfect—for no other particular reason or caveat. And you remain in gratitude through the daily struggles that give meaning and richness to your life.

Our ancestors devised animism and deities to thank for the bounties in nature. More recently in our history, tribal societies such as the Native Americans and the !Kung Bushmen of southern Africa thank the animal’s spirit for providing sustenance after it has been killed. If daily prayer or weekly services have a place in your life, you may be familiar with similar themes. But don’t overlook other modest ways to show gratitude in your day-to-day life. Giving yourself the luxury of a warm bath, making a phone call to grandma, or presenting a home-cooked meal to your family all count, too, if your intention is in the right place.

When you practice an attitude of gratitude, you appreciate what you have, not envy what you lack. It means you’re a good steward. You nourish and exercise your body and mind, cherish and respect your spouse, love your dog, keep your home clean and orderly, encourage your children. If you water your garden, you’ll watch it grow.

It’s the ability to see the beauty in simple things: a good red wine, a partner’s intimate touch, that post-workout calm, a great night’s sleep. The feel of the sun on your face, your feet in the wet sand, and your hands in the cool dirt. Or the thrill of pedaling down a rugged dirt trail, or the peace of floating on a quiet lake. Some time ago, for me, it was tasting the best shrimp of my life—grilled perfectly tender and flavorful in the shell with a mango-citrus dipping juice. Eating with my hands, sitting on the beach, enjoying the company of my wife and friends, I relished the full moment as much as that enticing platter.

When you practice gratitude, you create a happier take on your day-today world. But I am absolutely certain abundance only comes to people who appreciate the small gifts, the humble blessings, the basics. Oprah Winfrey is very much aware of this concept, saying it wasn’t until she went to Africa and had to carry water for every use of it that she realized her good fortune. She has said she hasn’t looked at water the same way again, never again has taken it for granted. Every time she turns on the tap, she is grateful.

Even material things, when combined with gratitude, multiply in value— your favorite T-shirt, your surfboard, your Ford Mustang. Practice gratitude regularly, make it a habit, and a curious thing begins to happen. Whether by an unscientific, mystical law of the universe, or simply by virtue of appreciating what you already have, you begin to open yourself to receive more. Such is the reward of good stewardship. And something else, even more curious: you actually find appreciation in some of life’s bitterest pills. Maybe your upbringing was not that great. It gave you character, didn’t it? So you got laid off? Great! You get an opportunity to explore a new adventure. Injured while training for your big marathon race? Ah, an opportunity to explore the novelty and fitness benefits of cross-training. Can you see how the more you appreciate, the more you see the glass half full rather than half empty, the more you feel gratitude—and you must feel it—the more aware you become of life’s hidden gifts? Can you see how the more you appreciate, the richer you become?

But don’t take my word for it. Let’s look at the science: University of California, Davis professor Robert Emmons, editor-in-chief of the Journal of Positive Psychology and author of Thanks!: How Practicing Gratitude Can Make You Happier, believes that living in gratitude is the single quickest and most efficient pathway to becoming happier. Yes, Emmons and other leaders in the burgeoning field of positive psychology can actually quantify this stuff, asserting that while familial genetics plays a large role in longevity, researchers have amassed significant data suggesting that up to 75 percent of longevity is related to psychological and behavioral factors. Emmons notes that chronically angry, depressed, or pessimistic people have long been observed to have an increased disease risk and shorter life spans. However, those who kept a simple “gratitude journal” for three weeks or longer reported better sleep, increased energy, heightened creativity, enthusiasm, determination, and optimism … and an increased desire for exercise. Now that’s something to be grateful for!

Gratitude gives way to simplicity, notes Sarah Ban Breathnach in Simple Abundance. Indeed, simplicity was the way of our ancestors, and they were richly rewarded for it. Owning things was not only irrelevant, but a hindrance to our ancestors’ semi-nomadic life. They met their needs on a daily basis without concern for surplus or excessive material possessions, trusting that the natural environment would provide. Marshall Sahlins refers to this way of life as “affluence without abundance” (also the “Zen road to affluence”), for such a non-materialistic value system affords many luxuries, including devotion to family and clan.

If this sounds like an idealist’s interpretation, consider the isolated hunter-gatherer societies across the globe today, who, like our ancient ancestors, work less, enjoy more leisure time, have no stress related to our Western mentality (i.e., the rat-race mentality) and enjoy arguably higher levels of life satisfaction in many enviable and profound ways. On a recent trip to South Africa, I witnessed this firsthand when we visited, by our materialistic standards, a dirt-poor village. The most memorable thing that came out of that experience for me was that everyone was smiling—all the time.

“When you practice an attitude of gratitude, you appreciate what you have, not envy what you lack.”

Not to discount the positive motivation of striving for career success and material gain (and the satisfaction that comes from succeeding), but we must also recognize the disadvantages of the modern mindset. Our culture, with its penchant for bigger, faster, stronger, tries to sell us the idea that the current more-is-better model is the norm, the inevitable, even the ideal. It’s the path of progress, we’re told, and we’d best keep up or get left behind. One can’t help asking, the path to whose progress?

The advertising firms on Madison Avenue have created a new standard in our collective psyche, defining in the shallowest terms who we should be, how we should look, and what we should have. I’m reminded of the dialogue in a scene from the popular television series Mad Men, depicting the dog-eat-dog world of 1960s advertising:

Advertising is based on one thing: happiness. And you know what happiness is? Happiness is the smell of a new car. It’s freedom from fear. It’s a billboard on the side of the road that screams reassurance that whatever you are doing is OK. You are OK.

Again, I’m not asking you to disavow your worldly possessions. Only to take inventory of the superfluous “stuff “: impulse buys and random things that strap you down with burden. If your world is cluttered with items that don’t bring you security, happiness, beauty, or meaningfulness, you are most certainly weighed down. Not only do these things clutter your exterior world but your interior world as well. More to take care of, more to haul around, more to box up and keep in storage. Liberate yourself, and get rid of it. And from this point on, commit to quality over quantity. Or as the minimalists say, live with less but only the best. Yes, less really can be more.

Celebrate life with affordable luxuries. Pull out your good china and silverware and light some long-stemmed candles … just because. Pick some flowers (or buy a cheap bouquet) and set them in your bedroom. Splurge on a basket of organic blueberries ($7 in some places!) or some fancy high-priced cappuccino. Use your imagination. What other ways can you find to indulge?

Start a gratitude journal. Make a comprehensive list of the things you are grateful for. See if you can list thirty, but strive for one hundred. I’ll give you five right now: your senses of sight, hearing, smelling, feeling, and tasting. Run with it. And be sure to come back to your journal often to record new entries. I recommend daily.

Live within your means, lower if possible.

Make a personal visit, a phone call, or write a handwritten letter. Express your Gratitude to someone who deserves it, but hasn’t been properly thanked.