Do one thing every day that scares you.

ELEANOR ROOSEVELT

HOW COULD LIFE FOR A hunter-gatherer be anything but an adventure? Just as our ancestors ventured to the edge once in a while, our genes expect the same from us. That’s right, every once in a while, we need to do something that pushes our limits and expands our boundaries. The urge is as natural as it is stirring. I’m talking about an occasional adrenaline rush to refresh and reset your cognitive and emotional compasses. The sort that suspends you in the heady risk of action, where time seems to stop, or at least slows down considerably. I’m talking about the kind of thing where you are fully engaged in the moment and become raw awareness, where the heightening of the senses can feel like skating along a razor’s edge that separates focus from fear.

There is indeed a certain thrill in testing our nerves, pondering how much farther down a darkening forest path we’ll go until fear or practical thoughts win out. Extreme physical endeavors—like freestyle skiing, mountain biking, climbing, surfing, white-water rafting, and so on—do the same. Such activities depend on sensory acuteness. Obviously, I wouldn’t recommend doing them without proper instruction, guided practice, and setting sensible limits. But in gaining mastery of these “sports,” we feel out and fine-tune our perceptiveness. We learn to trust our gut, Habit #6. A matter of a couple degrees in one’s lean on a steep hill can spell disaster for a skier. The angle and height of rifts in a whitewater scene tell a kayaker how to navigate. A climber learns the subtle difference between the feel of a foothold that is steady and one that is compromised or too shallow.

In this way, extreme endeavors and other spontaneous, inspired physical activities take us out of the rational and plant us wholly in the sensory. As suggested by Diane Ackerman, noted naturalist and author of Natural History of the Senses, extreme athletes reference a sense of “cleansing” and “divestiture” when explaining what draws them to their passions. They enter that precipice between actual danger and exuberant experimentation, tempting fate to relish the thrill of the chase, holding back just enough that they can withdraw in time to save their skins.

So much of life these days is routinized, regimented, parceled out for maximum efficiency and order. We spend a lot of it on a comfortable, safe plateau: such is the opportunity modern life affords. Few of us face any real hazard in a day. Few of us experience shocks to the system, those fleeting moments of hormesis, and are confronted by our own mortality in material, appreciable ways, or with any regularity. For the most part, it’s a profound benefit and historical boon to live in an age of unmatched certainty compared to that of our distant and not-so-distant ancestors. Yet, something in us feels the incongruity. We evolved facing threat. All those eons and thousands of generations molded our bodies and minds for acute risk and corresponding resilience. It’s unnatural to live without it. Something in our genetic capacity languishes. Something in our inherent nature withers or, alternatively, rebels. We become bored, overtaken by a sense of detached fatigue and inexplicable ennui.

In response, we fabricate risk with meaningless social drama or do genuinely dangerous, irresponsible, and stupid things that offer nothing to our health or self-actualization. Or we quietly, unconsciously acquiesce. There’s a price for this resignation, I think. As Ackerman puts it, “Where there is no risk, the emotional terrain is flat and unyielding, and, despite all its dimensions, valleys, pinnacles, and detours, life will seem to have none of its magnificent geography, only a length.”15

In the end, risk, as irrational as it is, is intuitive. Without it, we live stuck, inert, fixed at center. We give up the chance to explore the wild peripheries of living—and the reinvigoration that adventure offers even when we come back to the base of everyday life. When you honor these impulses, you return to ordinary life refreshed and deeply appreciative of your secure surroundings, a warm shower, a nourishing meal, a group of friends to regale with your tales of adventure. We are indeed a species that thrives in dichotomy.

Risk doesn’t have to be physical, of course, and I’m not suggesting you deliberately insert yourself in dangerous situations. I believe, however, that we benefit from activities that propel us to heightened mental and physical states, in which we further develop our often half-used senses and give ourselves over to a more primitive but powerful source of focus.

“There is indeed a certain thrill in testing our nerves, pondering how much farther down a darkening forest path we’ll go until fear or practical thoughts win out.”

Consider the sixteenth century’s Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan and his forty-three-thousand-mile journey to circumnavigate the globe. In search of a western route to the Spice Islands from Europe, he sailed down the South American coast—south, south, south into stormy seas and an increasingly brutal winter, with absolutely no idea where the southern tip was, or how long it would take to get there. Once around the continent, he fully expected to encounter the Spice Islands (near modern-day Indonesia) in short order, only to deal with an additional three months of sailing the endless (endless in the most profound sense of the word) waters of the Pacific.

Sitting here today, with Google Earth at our fingertips, it’s almost impossible to comprehend such a mysterious, treacherous, perspective-altering journey. Closer to home, I can recall with great detail the looks on my kids’ faces on the occasions of their first bike ride, first sleepover camp, and first time taking the car out solo. Certainly you have cherished memories of facing challenges, uncertainty, or even danger, and the resulting sense of personal accomplishment. Heck, I’ve failed numerous challenges, but grew from the experience of having tried. Like Magellan, we still possess our factory wiring for adventure—a continual desire to explore the limits of our physical and mental capabilities and our world in general.

What we are going for here is calculated risk. We access this through the physical realm because the intensity and graphic nature of physical challenges build confidence and bravery, virtues that can be applied to the other connections suggested in this book and life as a whole. Clearly, such risks are subjective, and you alone preside over your definition of what constitutes a calculated risk. A close friend of mine defines it as BASE jumping off El Capitan, Yosemite’s nearly three-thousand-foot-tall granite monolith. We’ve hiked the trail to the top together, but I can’t even bring myself to get close enough to the edge to watch his performance! Conversely, if you’re the type to test the limits of your motorcycle skills by revving up to 120 mph on the interstate at midnight, you may need to question if you are distorting this primal urge for adventure.

Pushing the envelope demands that you access the flow state. To reiterate the disclaimer, there is no need to put your life in danger to access this state of mind. Psychology professor Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi asserts that your challenges must sync with your abilities. Something too easy will bore you, but something too difficult, too dangerous, and too far outside of your comfort zone will likely cause you to disengage and become consumed by fear or frustration.

I can sense very well where the limitations of my snowboarding abilities lie, and I always stay well clear of crossing that line into the danger zone. I accept the calculated risks of sliding down a mountain slope, do my very best to mitigate these inherent risks by staying totally focused and cognizant of my limits. I believe strongly that the vast majority of “accidents”—not only in extreme sports but also in all physical activities—result from stupid mistakes rather than a natural consequence of the inherent risk. Often, the stupid mistake involved is the initial decision to attempt an endeavor with excessive risk. I respect and marvel at big-wave surfers, extreme skiers, and mountaineers, but I reject exceeding the limits of skill and common sense in the name of accomplishment.

“Like Magellan, we still possess our factory wiring for adventure—a continual desire to explore the limits of our physical and mental capabilities and our world in general.”

A skydiving friend of mine related a serious accident where he sustained numerous broken bones and damaged organs but lived to tell about it. The cause was a malfunctioning parachute that opened only partially due to improper packing. He typically paid an attendant at the skydiving center twenty bucks to pack his chutes. He was saving time so he could take more jumps! Upon returning to the sport, he decided to assume that job himself.

Whatever your parameters are, it’s essential to assess the risk-versus-reward factor carefully and harness all the concentration you can muster—not only to achieve the exalted flow, but to be safe. The goal is to proceed accordingly through exciting physical challenges, experience the thrill of being in the zone or the flow, increase your competency at your favorite activities, and broaden your horizons to pursue exciting new challenges in the future.

As you pursue Primal Thrills in the adrenaline-rush category, a certain element of physical risk and danger may be involved. But the same holds true anytime you zone out in daily life. In fact, when you access the flow state and test your boundaries, you invariably improve your ability to focus, heighten your awareness of risk and danger, and access an elevated mental and physical state where your attention becomes primal instead of scattered.

If you’ve walked by the pickup basketball game in the park every day at lunch but never summoned the guts to play, jump in there one time and see if you can hang. Hey, you might get embarrassed, but you can hold your head higher than that guy who walks by every day and never takes his shot. Did you high jump, throw the shot, or pole vault “back in the day”? See if you can reawaken old passions like these through a local community sports program.

If you already have a certain level of devotion to serious physical challenges, see if you can take things to the next level. In Bone Games: Extreme Sports, Shamanism, Zen, and the Search for Transcendence, author Rob Schultheis discusses how being pushed to the edge of his physical limits allowed him to access a higher level of consciousness and peak performance. He relates accessing the flow or the zone during a perilous mountain climbing experience. Having suffered significant injuries in a fall, he was stuck in the wilderness with a dangerous storm approaching. Inspired at a primal level by his dire circumstances, he proceeded to descend a treacherous mountain pass with uncanny speed and mastery. In Schultheis’s words:

Something happened on that descent, something I have tried to figure out ever since, so inexplicable and powerful it was. I found myself very simply doing impossible things: dozens, scores of them, as I climbed down Neva’s lethal slopes. Shattered, in shock, I climbed with the impeccable sureness of a snow leopard, a mountain goat.

When Schultheis healed his body and returned to the scene of his adventure later, he could scarcely believe what he had accomplished and the danger level that he’d barely blinked at.

To follow are a few more suggestions for Primal Thrills, but I want to emphasize imagination and creativity on this connection. There are plenty of ways to push your boundaries in your everyday life, maybe volunteer to do some public speaking or ask for that much-deserved raise. But overall I want you to think about outdoor, natural settings, minimal logistics, and pursuing the purity of the experience. See if you can call up a healthy bit of fear, anxiety, and uncertainty of outcome—within reason of course—in order to access a higher level of consciousness and peak performance.

Amusement parks. Challenging the law of gravity is a surefire way to get a safe rush. Granted, the long lines and cotton candy stands might not be as badass as Schultheis scrambling down a dangerous slope during a lightning storm, or modern-day Magellans racing in the Vendée Globe. However, the waterslides, the roller coasters, and the ever-more sophisticated and gasp-inducing contraptions rising from your nearest amusement park are a harmless way to get crazy and extreme. What’s more, your genes don’t know the difference between a life-or-death adrenaline rush and a simulated one at the amusement park.

Night hike. Join a local recreation group that offers organized night hikes or snowshoe outings. Expect some sweaty palms, an elevated heart rate, and jittery nerves as you enter into the unfamiliar world of darkness. As you proceed with your adventure, a sense of focus and peace will edge out your initial fears. In a short while, your hardwired instinct and sensory acuity will take over and you’ll realize you’re somehow able to balance your body deftly along a dark, rocky trail. You’ll hear every small sound and identify the exact source. As other long-buried, primal abilities present themselves, you’ll gain courage and confidence that is hard to acquire via the quarterly sales contest or adult softball league playoffs.

Competition. Anything that gets your competitive juices going will facilitate a flow experience. Join that pickup basketball game, organize a neighborhood Ping-Pong tournament, or pull the trigger and enter a mud run, beach volleyball tournament, or mini triathlon.

Jump off something. Jumping from an elevated perch into water could be the quintessential Primal Thrill. Find a river, lake, or ocean with rocky shorelines and a suitable perch from which to launch. Failing these options, go for the high-diving board at a local swimming pool. Caution and good sense are advised here. First, if you haven’t seen anyone else jump from the spot, you’re taking a risk! Second, I go feet-first when jumping into any body of water besides a swimming pool. If the water is not crystal clear, I first dive down and thoroughly examine the landing area to ensure it’s of a safe depth and there are no debris or protruding objects beneath the surface.

While it’s hard to do damage jumping from 10 feet or less, anything over that height requires correct form to prevent injury. For example, even something as innocuous as hitting the surface with your arms outstretched can tear a rotator cuff when you are a couple stories high and beyond. Also, it’s a great idea to wear Vibrams or sneakers to protect your bare feet from impact trauma.

Martial arts. This affords mind/body benefits along with all-around physical conditioning. Breaking bricks—what a great metaphor for becoming a more powerful and confident person!

Mini adventure race. Choose three or more modes of transportation and establish a challenge to go from point A to point B using various forms of locomotion (human-powered only). For example, take a bike ride to the lake, swim to the opposite shore, hike the perimeter to return to your bike, and then ride back home. Throw in a skateboard, scooter, or—if you have winter conditions—snowshoes, cross-country skis, and ice skates. City-dwellers can try this: hike two blocks to a building with twenty-plus stories and accessible stairs. Climb and descend the staircase, then hike another two blocks to a new building and repeat.

Nature challenges. Mountain climbing, rock climbing, water sports (swimming, surfing, standup paddling, waterskiing, wakeboarding, wakesurfing), and winter sports (downhill and cross-country skiing, ice skating) all entail synchronizing your physical efforts with natural forces—going with the flow. You haven’t lived until you have tried standup paddling or wake surfing (yep, sans rope behind a ski boat). Moving within a naturally varied environment like water virtually demands that you transition out of an analytical state into a flow-like state.

Photo scavenger hunt. A game director is required to administrate this game. Form several teams (the more, the better!) of two or three people. Arm each team with a digital camera. The game director prepares a list of items to photograph, with corresponding point values for degree of difficulty. On the photo list, describe points of interest in your area, riddles that reveal a specific location, and outrageous, difficult-to-orchestrate situations (for instance, a photo of a team member getting shampooed at a hair salon; eating watermelon with a stranger on a bus bench; sitting astride a Harley Davidson motorcycle; with a non-domesticated animal visible in the picture; or submerged in a pool holding a bag of potato chips).

Begin by distributing the photo lists to the teams, start the clock, and establish a return time of two to three hours. Upon return, each team’s photos are evaluated, points tabulated, and a winner declared. Printing out the photos onto a collage for each team makes for a great souvenir!

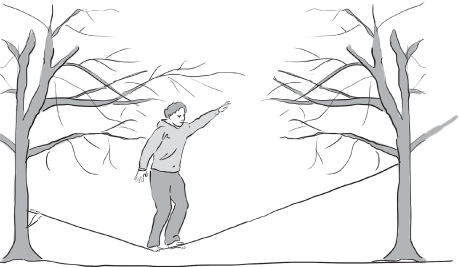

Slacklining. It’s such a simple endeavor, but one of powerful symbolism. A slackline is a flat nylon tightrope a couple inches wide that you suspend from two anchor points, such as trees, or strong posts or poles. As the name suggests, the line is not taut under the user’s weight; rather it will stretch and recoil under the load. It looks easy, but it’s a tremendous challenge to simply mount the line and keep your footing. The dynamic tension in the line can send you flying off with the slightest disturbance to your center of gravity.

Slacklining is an activity that engrosses you immediately. An approach that’s too casual will send you flying off the rope; try too hard and you might soon find your legs doing the dreaded sewing machine (uncontrollable twitching). But when you can get into the sweet spot of balance and start taking steps up and down the line, it’s a blissful, connected feeling. Search YouTube for “Slackline World Cup” and you’ll see the amazing exploits of “trickliners” who use the line like a trampoline, launching to perform aerial tricks and then landing gracefully back on the skinny line.

Speed golf. Wait until twilight and tee off on an empty course. Carry a junior golf bag with just a handful of clubs. Jog from shot to shot and play quickly, but at the same time making your best effort to score well, including putting. Count one point for each stroke and each minute on the course to produce a total score. World champion Jay Larsen once shot a 71 on a regulation-length course in thirty-seven minutes, for a speed golf total of 108!

Ultimate Frisbee. If you haven’t tried it, you are missing out on one of the most enjoyable games around! All ages and ability levels can play safely together, with minimal equipment or logistics, in groups of varied numbers. I recommend a minimum of six players and a maximum of sixteen. Depending on the size of the group, a field of 50 to 100 yards length and 35 to 50 yards width is ideal. The game (the proper term is simply “Ultimate,” since Frisbee is actually a brand name) is somewhat like soccer with a flying disc. Teams try to score a goal by covering the length of the field passing the disc and crossing the end line.

You can pass forward or backward to any open teammate but cannot run if you are the passer. If a team on offense drops the disc, the other team takes possession on the spot immediately and tries to pass to open players and get across the opposite end line—it’s nonstop action! Players should match up with opponents appropriately by size and ability, covering players from the opposing team in man-to-man defense style. However, no physical contact with an opponent is allowed except incidental contact going for the flying disc. These rules allow for the full and safe inclusion of a diverse group.