Chapter 10

A Tale of Two Kingdoms: 1 and 2 Kings and 1 and 2 Chronicles

In This Chapter

Intellectualizing with Solomon

Intellectualizing with Solomon

Surviving the division of a nation

Surviving the division of a nation

Fighting Baal and King Ahab with the prophets Elijah and Elisha

Fighting Baal and King Ahab with the prophets Elijah and Elisha

Overthrowing governments with Jehu

Overthrowing governments with Jehu

Reforming the nation with Hezekiah and Josiah

Reforming the nation with Hezekiah and Josiah

Destroying Jerusalem with Nebuchadnezzar

Destroying Jerusalem with Nebuchadnezzar

Witnessing ancient spin doctors in the Books of Chronicles

Witnessing ancient spin doctors in the Books of Chronicles

T he Books of Kings and Chronicles continue the drama of ancient Israel’s monarchy. At the conclusion of 2 Samuel, David is sitting on the throne as king over a unified nation. In addition, he has secured the location and supplies for God’s “house” — the Temple. At the beginning of 1 Kings, David successfully passes the throne to his son, Solomon, who fulfills his father’s dream of building the Temple. What’s more, Solomon surpasses his father’s dreams by making Israel one of the wealthiest and most powerful nations in the world. But then things take a drastic turn for the worse.

When Solomon dies, the kingdom splits into two kingdoms — Israel and Judah. Then, after two centuries of political coups and spiritual conflict, the northern kingdom of Israel falls to the mighty Assyrian Empire in 721 B.C.E. Less than 150 years later, the southern kingdom of Judah meets its end at the hands of the Babylonians, who conquer Jerusalem and destroy Solomon’s Temple in 586 B.C.E.

Although filled with tragedy, the Books of 1 and 2 Kings and 1 and 2 Chronicles give us some of the most memorable episodes and colorful characters found in the Bible. This is the tale of two kingdoms.

The “Golden Age” of Solomon

Solomon is David’s second son by Bathsheba, their first son having died as punishment for their adulterous (and murderous) affair — see Chapter 9. Solomon’s reign has been called the “Golden Age” of ancient Israel. Yet, how Solomon ascended to the throne was anything but “golden.”

Solomon’s succession (1 Kings 1)

When 1 Kings opens, David is old and can no longer fulfill his royal duties, including performing sexually (or as the King James translates it, “he gat no heat”). That may sound weird (especially in the King James), but leadership in antiquity was intimately tied to virility. Therefore, a beautiful girl named Abishag is brought to David’s bed, but as the text reads “ he was not intimate with her” (1 Kings 1:4). David’s sons immediately begin maneuvering for the throne.

Adonijah, David’s eldest surviving son, is the most obvious choice to be the new king, but Solomon also feels he has a claim. Bathsheba, who has a vested interest in seeing her son, Solomon, on the throne, reminds David of an oath he allegedly made saying Solomon would be the next king. David, perhaps feeling he’s having a “senior moment,” declares Solomon king.

Meanwhile, just outside Jerusalem’s walls, Adonijah is declared king by his own supporters. However, when they hear of David’s choice of Solomon, they abandon their cause. Adonijah, seeing his desperate predicament, rushes to God’s altar and clings to it. Adonijah’s actions reflect what was commonly understood in the ancient world as an appeal for mercy.

Solomon promises not to kill his older brother on one condition: he must never again conspire for the throne. Adonijah agrees, and he and his supporters are spared (for the moment). Soon, Solomon is summoned to his father’s deathbed to receive his parting instructions. In a scene that is reminiscent of The Godfather, David tells Solomon to kill two men:

Joab, David’s general, who killed two men who were under David’s protection. He also backed Adonijah in his recent bid for the throne.

Joab, David’s general, who killed two men who were under David’s protection. He also backed Adonijah in his recent bid for the throne.

Shimei, the previous king’s (Saul) kinsman, who turned against David during a coup (see Chapter 9). Although Shimei “repented” of this “folly” when David regained the throne, he still couldn’t be trusted.

Shimei, the previous king’s (Saul) kinsman, who turned against David during a coup (see Chapter 9). Although Shimei “repented” of this “folly” when David regained the throne, he still couldn’t be trusted.

David’s instructions may sound harsh. However, David knew that transitions between monarchs were precarious times for a nation and that treacherous people were capable of treacherous actions during such transitions.

On a more positive note, David also tells his son to love and obey God, for in doing so his kingdom will prosper, and he will be blessed (1 Kings 2:1–4). Then David, the shepherd boy who became a king, dies.

Solomon’s wisdom (1 Kings 2)

After David’s death, Solomon takes quick action to secure his throne. Beyond following David’s final instructions to kill Joab and Shimei, Solomon also kills his brother, Adonijah. “Now wait a minute,” you may be saying, “David never said anything about that!” True, but, as we say today, Adonijah “asked for it.” Having lost the kingdom, Adonijah asks Solomon for a “consolation prize”: the beautiful Abishag. Solomon sees this request as another bid for the throne, because, if Adonijah can perform sexually with Abishag, with whom the previous king, David, couldn’t “get heat” (that is, perform sexually), then Adonijah will have demonstrated his capacity to rule. Therefore, Solomon denies the request, and orders Adonijah’s execution.

There remains only one other important participant in Adonijah’s failed bid for the throne: the High Priest Abiathar. Yet, rather than kill Abiathar, Solomon pardons him due to his former status as High Priest. The key word here is former. Solomon deposes Abiathar and banishes him to Anathoth, a small town just close enough to Jerusalem to keep an eye on him, but just far away enough to keep him out of the affairs of state.

Acknowledging Solomon’s wise request (1 Kings 3:1–15)

Solomon now sits securely on the throne. In addition, he follows his father’s advice to love and obey God. Then, one night, God appears to Solomon and says, “Ask for whatever you want from Me” (1 Kings 3:5). Rather than ask for a long life, riches or power, Solomon asks for wisdom “to rule Your people and to distinguish between good and evil.” This request so pleases God that He not only gives Solomon wisdom, but He gives the rest as well: longevity, wealth, and power. Solomon doesn’t let his newfound gifts go to waste, but becomes a prolific author, songwriter, and scholar. Yet, the story that best exemplifies Solomon’s wisdom involves two prostitutes and a baby.

Dividing the truth with Solomon’s wisdom (1 Kings 3:16–28)

One of the most important duties of any king in the ancient world was to preside over difficult legal cases. And one day, Solomon is presented with a doozy. Two prostitutes come to Solomon with a baby, both claiming to be the mother. One prostitute explains that the other accidentally rolled over on her own child and suffocated him, and then exchanged babies with her while she was asleep. The other prostitute said that was a lie, as the living baby was definitely her own. Because this is before DNA testing, Solomon comes up with another plan: “Let’s cut the baby in two, then you can both have half.” While the one woman acquiesces, the other speaks up, “Please! Give her the baby. Only don’t harm the child!” (1 Kings 3:26). Giving the baby to the woman who just spoke, Solomon says, “You’re the real mother.”

Solomon’s building projects: the Temple and other treasures (1 Kings 5–7)

After securing his reign, Solomon fortifies his kingdom. He rebuilds the wall and gate systems of several cities and establishes regional centers from which he and his officials can administer the nation. Additionally, he builds stables to house his abundant horses and chariots. Solomon also increases maritime trade to the south by constructing a fleet of ships on the Red Sea. Yet, most of Solomon’s time and money is spent on building projects in his capital city of Jerusalem. Solomon enlists the help of Phoenician craftsmen and purchases other goods from his ally, King Hiram of Tyre. Solomon spends the next 13 years constructing his elaborate palace, and 7 years building a Temple for God next door. (The palace’s location near the Temple symbolized Solomon’s privileged status as God’s appointed ruler.) When the Temple is completed, the priests move God’s cultic equipment from the Tabernacle to the Temple, and a feast is held for 14 days in celebration.

Yet will God really dwell on earth? The highest heavens cannot contain you, much less this Temple I have built.

—1 Kings 8:27

Solomon’s last days (1 Kings 9–11)

Solomon marries literally hundreds of foreign princesses to build peaceful relationships with the surrounding nations. When combined with his other wives and concubines, Solomon’s spouses number 1,000, which is just asking for trouble. And sure enough, trouble comes as Solomon gets older. First, Solomon gradually loses his commitment to monotheism (the belief that there is only one God), and begins succumbing to the religions of his foreign wives. This doesn’t sit well with God, who vows to take all but one tribe away from Solomon’s kingdom. Yet, because God so loved Solomon’s father, David, He postpones punishment until Solomon’s reign is over.

Beyond his many wives, close examination of the biblical record reveals that Solomon makes some other mistakes. Solomon’s administration oppresses the northern tribes for the benefit of his own tribe of Judah. Solomon’s large-scale building projects cost a fortune, and increased taxes are a necessity. To collect funds, and also to increase his power base by weakening tribal alliances, Solomon creates 12 administrative districts based not on the traditional tribal borders but rather on geographical features and towns. Solomon also requires each of these districts to provide forced laborers one month out of the year in order to work on his various building projects. This “redistricting” and forced labor is difficult to accept, especially considering the Israelites’ past history as slaves in Egypt. Moreover, Judah isn’t taxed at all, though they receive the largest benefits (fortifications) from the tax.

Further angering the northern tribes, Solomon sells 20 towns from northern Israel to the Phoenician king Hiram. And, although the northern tribes once hosted the Tabernacle, now the Jerusalem Temple permanently houses the Ark of the Covenant, thus diminishing their religious influence. If things weren’t bad enough, during the latter portion of Solomon’s reign, several neighboring kingdoms that David conquered break away from Israelite control. Moreover, the northern tribes threaten to withdraw their support from Solomon and follow their own leader, Jeroboam, an official appointed by Solomon to supervise labor. Solomon makes an unsuccessful attempt to kill Jeroboam, who flees to Egypt, where he remains until Solomon’s death.

Solomon, after a long and eventful reign of 40 years, passes away, leaving his throne to his son Rehoboam.

Check out the new digs

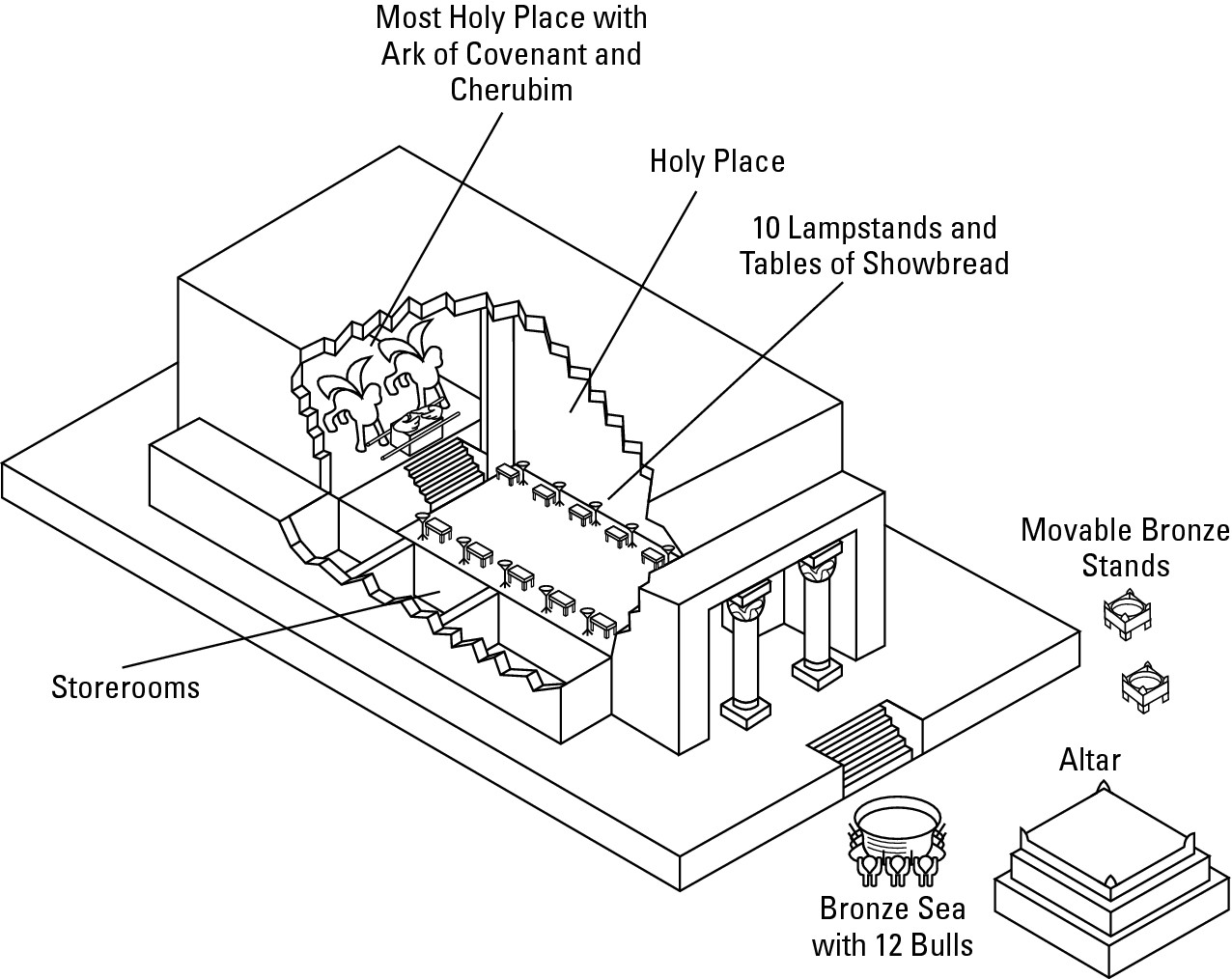

The Temple and its furniture symbolized Israel’s special relationship with God. In the court of the Temple stood a large altar for sacrifices, which the priests offered for Israel’s sins and to express thanks to God. The large water basin or Sea was used for ritual cleansing of the priests and altar, as both needed to be pure in the presence of God. Inside the Temple, in the room called the Holy Place, stood ten tables with offerings of bread, acknowledging God’s ongoing provision of food. Also in this room were ten lamps, which burned continually, a symbolic

expression of God’s enduring covenant with Israel. The most sacred room, called the Most Holy Place or the Holy of Holies, was situated in the back of the Temple and symbolized God’s throne room. Inside were two massive statues of cherubim (biblical monsters — part lion, eagle, and human; see Chapter 3), overlaid with gold and which figuratively stood guard above the Ark of the Covenant, the golden box housing the tablets of the Ten Commandments (discussed in detail in Chapter 7).

Sheba visits Solomon

One of the most famous people to visit Solomon is the Queen of Sheba (1 Kings 10), who journeys northward to see if all she heard about Solomon and his wisdom and wealth is true. Hollywood repeatedly portrays the Queen of Sheba as a European woman wearing a leopard-skin bikini. Nevertheless, Sheba is located in the southwestern Arabian peninsula in modern Yemen (or nearby in Ethiopia), and capitalized on the lucrative spice and incense trade that originated in that area. The sap from various desert trees in Sheba produces incense such as myrrh and frankincense, and the bark from Sheban plants composes cinnamon and other spices. The Bible’s account of the queen’s procession to see Solomon lists quite a parade — she and her traveling companions bring along with them camels, spices, gold, and precious stones, which she presents to Solomon. He in turn pays her “whatever she desired.”

Witnessing the Division of Israel

Solomon’s son and successor Rehoboam doesn’t seem to have inherited his father’s brains. In fact, due to his foolishness, the nation divides in two.

Snips and flails and scorpion’s tails: Rehoboam divides a nation (1 Kings 12)

Rehoboam travels north to reaffirm his position as its new king. However, the northern tribes want to know if he will continue Solomon’s policy of overtaxing and overworking them. Rehoboam meets with his advisors, and while his elders wisely tell him to promise the north anything it wants in order to secure his power, the younger advisors instruct him to show these rebels who’s the boss. Rehoboam foolishly listens to the younger crowd and tells the northern tribes: “My father made your yoke heavy, but I will add to your yoke; my father beat you with whips, but I will beat you with scorpions!” (1 Kings 12:14). In response, the northern tribes secede from the union, which ushers in the Period of the Divided Monarchy (928 B.C.E.–721 B.C.E).

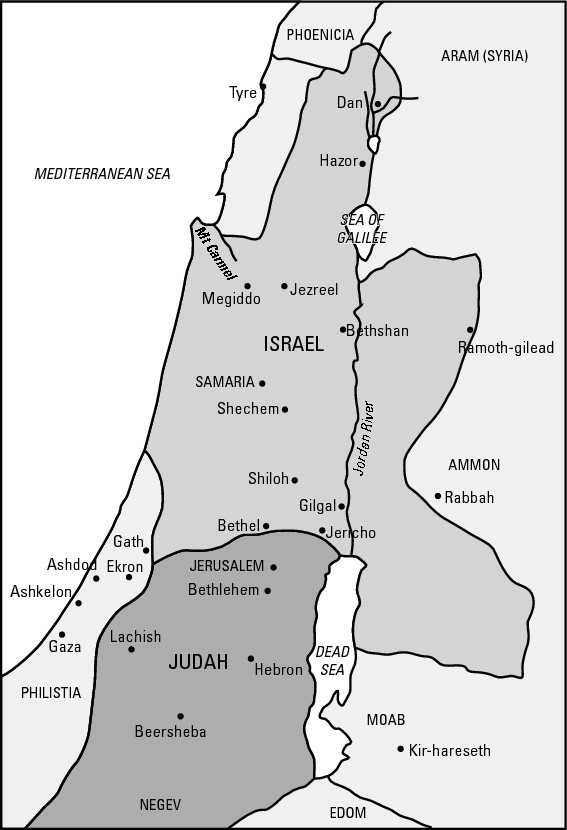

Israel, as the northern kingdom is now called, consists of the northern ten tribes of Israel (see the map in Figure 10-1). Numerous dynastic transitions over the next 200 years result in a variety of capital cities, but most predominant is Samaria, which becomes an alternate name for this kingdom.

Israel, as the northern kingdom is now called, consists of the northern ten tribes of Israel (see the map in Figure 10-1). Numerous dynastic transitions over the next 200 years result in a variety of capital cities, but most predominant is Samaria, which becomes an alternate name for this kingdom.

Judah, as the southern kingdom is called, remains comparatively stable. The capital of Judah remains in Jerusalem, and the dynasty established by David is one of the longest in history, lasting for over 400 years.

Judah, as the southern kingdom is called, remains comparatively stable. The capital of Judah remains in Jerusalem, and the dynasty established by David is one of the longest in history, lasting for over 400 years.

|

Figure 10-1: A map of Israel, the divided kingdom. |

|

| Kings of Judah | Kings of Israel |

|---|---|

| Rehoboam (928–911) | Jeroboam I (928–907) |

| Abijam or Abijam (911–908) | Nadab (907–906) |

| Asa (908–867) | Baasha (906–883) |

| Jehoshaphat (870–846) | Eliah (883–882); Zimri (882) |

| Jehoram or Joram (851–843) | Omri (882–871) |

| Ahaziah or Jehoahaz (843–842) | Ahab (873–852) |

| Athaliah (842–836) | Ahaziah (852–851) |

| Jehoash or Joash (836–798) | Jehoram or Joram (851–842) |

| Amaziah (798–769) | Jehu (842–814) |

| Azariah or Uzziah (785-733) | Jehoahaz (817–800) |

| Jotham (759–743) | Jehoash or Joash (800–784) |

| Ahaz (743–715) | Jeroboam II (788–747) |

| Hezekiah (715–687) | Zechariah (747); Shallum (747) |

| Manasseh (687–642) | Menahem (747–737) |

| Amon (641–640) | Pekahiah (737–732) |

| Josiah (640–609) | Pekah (735–732) |

| Jehoahaz (609) | Hoshea (732–722) |

| Jehoiakim (608–598) | |

| Jehoiachin (597) | |

| Zedekiah (597–586) |

Idol time: Jeroboam and the golden calves (1 Kings 13–14)

Israel’s first king, Jeroboam, immediately begins building his kingdom. First he constructs a palace. Then, motivated by a fear of losing his subjects when they travel to Jerusalem for the major religious festivals, he builds two cult centers within his borders. One is at the northern extremity of Israel at the site of Dan; the other is in the south at Bethel, right on the border between Judah and Israel (refer to Figure 10-1). At both sites, he sets up a golden calf (actually a young bull, a common symbol of virility in the ancient Near East). Then, just as Israel’s ancestors had done after Aaron built a golden calf (see Chapter 7), Jeroboam declares, “These are your gods, O Israel, who brought you up out of the land of Egypt!” (1 Kings 12:28).

What happened to the Ark of the Covenant?

The Ark of the Covenant, the most sacred relic in ancient Israel, simply disappears without direct mention in the historical record. We know it moved from the Tabernacle to Solomon’s Temple in 960 B.C.E., and we are fairly sure that it wasn’t among the relics taken to Babylon in 586 B.C.E. Several possibilities for how it vanished have been proposed:

Because Shishak “took away everything” from the Temple, some scholars (and Steven Spielberg in Raiders of the Lost Ark) theorize that Shishak took the Ark to his capital city of Tanis in the eastern Nile Delta of Egypt.

Because Shishak “took away everything” from the Temple, some scholars (and Steven Spielberg in Raiders of the Lost Ark) theorize that Shishak took the Ark to his capital city of Tanis in the eastern Nile Delta of Egypt.

According to 2 Maccabees 2:1–7 in the Apocrypha, the prophet Jeremiah hid the Ark of the Covenant on Mount Nebo, the same place from which Moses spies the Promised Land immediately before his death.

According to 2 Maccabees 2:1–7 in the Apocrypha, the prophet Jeremiah hid the Ark of the Covenant on Mount Nebo, the same place from which Moses spies the Promised Land immediately before his death.

The Talmud suggests that King Josiah of Judah hid the Ark in one of the many storerooms beneath the Temple in Jerusalem.

The Talmud suggests that King Josiah of Judah hid the Ark in one of the many storerooms beneath the Temple in Jerusalem.

Many Ethiopian Christians believe that the Ark resides today within the Church of Mary Zion in Aksum. This belief is based on a classic Ethiopic text that records that King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba had a son named Menelik who brought the Ark to Ethiopia.

Many Ethiopian Christians believe that the Ark resides today within the Church of Mary Zion in Aksum. This belief is based on a classic Ethiopic text that records that King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba had a son named Menelik who brought the Ark to Ethiopia.

Where the Ark really is, if it still exists, remains a mystery (though we’re partial to Spielberg’s contention that it resides in a U.S. government warehouse in an unmarked crate)

Cut to Judah: Shishak’s campaign (1 Kings 14:25–28; 2 Chronicles 12)

Israel’s Kingdom from Jeroboam to Ahab

The politics of ancient Israel are messy even by antiquity’s standards. Rarely does a dynasty last beyond a couple of generations.

Jeroboam I rules from 928 to 907 B.C.E. and passes the crown down to his son, Nadab in 907.

Jeroboam I rules from 928 to 907 B.C.E. and passes the crown down to his son, Nadab in 907.

Nadab is assassinated in 906 B.C.E. after a reign of only two years.

Nadab is assassinated in 906 B.C.E. after a reign of only two years.

Nadab’s assassin and usurper, Baasha, kills all of Jeroboam’s male descendants to better ensure his reign from 906 to 883 B.C.E.

Nadab’s assassin and usurper, Baasha, kills all of Jeroboam’s male descendants to better ensure his reign from 906 to 883 B.C.E.

Baasha’s son and successor Elah rules for two short years (from 883 to 882 B.C.E.) before he is assassinated along with his male descendants. Elah is killed by his servant Zimri, the commander of the Israelite chariots, who seizes power by killing Elah while the monarch is drunk.

Baasha’s son and successor Elah rules for two short years (from 883 to 882 B.C.E.) before he is assassinated along with his male descendants. Elah is killed by his servant Zimri, the commander of the Israelite chariots, who seizes power by killing Elah while the monarch is drunk.

Zimri’s coup lasts a mere seven days, however, as the military backs another commander, Omri, and burns the usurper Zimri in his house.

Zimri’s coup lasts a mere seven days, however, as the military backs another commander, Omri, and burns the usurper Zimri in his house.

Omri’s dynasty is one of the longest, lasting 40 years, and includes Omri (ruling from 882 to 871 B.C.E.), Ahab (ruling from 873 to 852), Ahaziah (ruling from 852 to 851), and Jehoram (ruling from 851 to 842).

Omri’s dynasty is one of the longest, lasting 40 years, and includes Omri (ruling from 882 to 871 B.C.E.), Ahab (ruling from 873 to 852), Ahaziah (ruling from 852 to 851), and Jehoram (ruling from 851 to 842).

The time of Omri’s dynasty is marked by frequent wars and coalitions to stop expanding neighbors. This threat seems to produce the political marriage between Ahab, as crown prince, and the Phoenician princess Jezebel, whose idolatrous exploits bring them into conflict with God’s prophet, Elijah.

Ahoy there, King Ahab! (1 Kings 16–22)

The tenth king of Israel, Ahab, and his wife, Jezebel, are among the most vilified characters in the Bible. This is for good reason: They both commit horrible crimes against their subjects for personal gain. They also endorse the worship of the Canaanite god Baal and Baal’s divine girlfriend, Asherah.

Ahab, like most of the kings of Israel before and after, worships a variety of deities. However, even worse than his apostasy is a crime he commits against a neighbor. Next door to Ahab’s palace lives a man named Naboth, who owns a vineyard. Ahab wants Naboth’s vineyard because it is choice land. However, Naboth refuses to sell it. Ahab is so upset after being rebuffed that he returns home and refuses to eat. Jezebel tells Ahab to relax, saying she will take care of everything. Jezebel pays two of her subjects to lie, saying that they overheard Naboth cursing the king and God. Because these are capital offenses, Naboth is summarily executed, and his property goes to Ahab.

Ahab and Jezebel would have gotten away with this crime were it not for God and His prophet Elijah. God tells Elijah to confront Ahab, who is presently looking over his newly acquired property. When Elijah finds Ahab in Naboth’s vineyard, he tells him that both he and Jezebel will die for what they’ve done. Elijah pulls no punches: “In the place where dogs licked up the blood of Naboth, so dogs will lick up your blood. Yes, yours!” (1 Kings 21:19). This eventually will come to pass, but before their undoing, Ahab and Jezebel make a lot more trouble for Israel. Yet, as in the case of Naboth’s vineyard, at each step of the way they have to reckon with God’s prophet, Elijah, and his dutiful understudy, Elisha.

Elijah and Elisha’s excellent adventures

Elijah and Elisha are extraordinary prophets, and their journeys and battles epitomize a complete devotion to God. Elijah is initially called by God to travel across the Jordan River into the desert where he is fed by ravens. Soon thereafter, Elijah travels to Phoenicia where he multiplies food and brings a widow’s son back to life. Yet, it is when God sends Elijah to the Israelite king Ahab for a showdown at Mount Carmel with the Canaanite god Baal that he distinguishes himself as a prophet to be reckoned with.

Elijah versus the prophets of Baal (1 Kings 18)

Distraught over Israel’s apostasy under Ahab and Jezebel, Elijah gathers all of Israel to Mount Carmel where he has scheduled a competition. The god who can send lightning down from heaven to consume a sacrifice is the god worthy of Israel’s worship. The people agree.

Pouring water on his sacrifice three times in order to show that God can start a fire even with dampened wood, Elijah then begins to pray. Suddenly, fire descends from heaven and consumes the sacrifice. It is a fantastic victory for God and Elijah, and all the people acknowledge that “The LORD, He is God!” At Elijah’s command, all the prophets of Baal are seized and killed. Elijah then runs faster than Ahab’s chariot back to the royal city of Jezreel where he heralds the news. Jezebel, fed up with Elijah’s “God-talk” and angered over the loss of her prophets, vows to kill the prophet. Remarkably, the man who just stood up to the prophets of Baal, flees for his life.

Elijah’s Moses-like exodus (1 Kings19)

Elijah travels south to Mount Horeb, another name for Mount Sinai, where God gave Moses Israel’s Law (see Chapter 7). Along the way, Elijah is miraculously sustained for 40 days without food, which is reminiscent of Israel’s earlier wilderness wanderings of 40 years under Moses. At Mount Horeb, Elijah experiences an earthquake, a great wind, and fire, which is also reminiscent of what the Israelites experienced here when Moses met with God. However, God is said not to be in any of these phenomena. The reason? These phenomena have become too closely associated with the storm god, Baal. God, therefore, reveals Himself to Elijah in the sound of a thin whisper. Then God asks Elijah, “What are you doing here?” Without waiting for an answer, God tells Elijah to perform three tasks:

Anoint an Israelite military commander named Jehu as Israel’s king.

Anoint an Israelite military commander named Jehu as Israel’s king.

Anoint the next king of Israel’s neighbor, Aram.

Anoint the next king of Israel’s neighbor, Aram.

Appoint Elisha as his successor.

Appoint Elisha as his successor.

Elijah performs the third task first, and the other two are left to Elisha, who takes Elijah’s place in dramatic fashion.

Swing low, sweet chariot: Passing the torch to Elisha (2 Kings 1)

Elijah eventually finds Elisha, and they travel together for a short time. Wanting some privacy from an entourage of prophets who are following them, Elijah takes off his cloak and touches the Jordan River, which miraculously parts so they can cross over (again similar to Moses, who parted the Red Sea). On the other side of the Jordan, Elijah says farewell to his friend, and a fiery chariot descends from heaven and takes Elijah away in a whirlwind (2 Kings 2:11).

Now going solo, Elisha crosses back over the Jordan River into Israel, and picks up where Elijah left off in working wonders on behalf of God (see 2 Kings 2–13). Among Elisha’s miracles are a floating axe-head, getting two bears to maul 42 youths for making fun of his baldness, multiplying food, and reviving a dead man. Ahab, Elijah’s old nemesis, dies in battle, and just as Elijah predicted, dogs lick his blood.

Israel’s Kingdom From Ahaziah to Jehu

The hostile politics between Israel and Judah are postponed by a marriage alliance between Ahab’s sister, Athaliah, and the crown prince of Judah, Jehoram (also known as Joram). Athaliah and Jehoram have a son, Ahaziah, who eventually becomes king of Judah. He then joins forces with his cousin, Joram (different from Judah’s Joram), who is the King of Israel, and they fight against Aram, Israel’s neighbors to the north. However, during the battle, Joram is wounded and retreats with Ahaziah to recuperate at Jezreel (2 Kings 8). It is while Ahaziah and Joram are at Jezreel that one of the bloodiest revolutions in the Bible takes place, and the sins of Ahab and Jezebel are finally paid in full.

Jehu’s political coup and religious reform (2 Kings 9–10)

Jehu, as the commander of King Joram’s army, remains near the frontlines of the battle while his king recuperates at Jezreel. As he is meeting with his officers, a prophet sent by Elisha walks into the room and anoints him king. The prophet then informs Jehu that he is to be God’s chosen vessel for punishing Ahab’s descendants for Ahab’s and their sins. When word of this event reaches the Israelite troops under Jehu’s command, the camp expresses their support. Jehu quickly mounts his chariot and sets off to Jezreel.

When Joram and Ahaziah see Jehu approaching, they send a horseman to find out his intentions. The horseman never returns — instead, he joins Jehu’s side. When another horseman does the same thing, the two kings themselves set off toward Jehu. When they meet, Joram and Ahaziah inquire, “Is it peace, Jehu?” When Jehu’s treachery becomes apparent, it is too late. Jehu, citing the religious heresy of Joram’s mother, Jezebel, shoots an arrow through Joram’s heart. Ahaziah turns to flee, though he also is mortally wounded. Jehu then enters Jezreel to begin securing his reign.

Jezebel, held up in Jezreel, does not live long. When she sees Jehu approaching, she paints her eyes and adorns her head. These actions have long been misinterpreted as her attempt to seduce Jehu and save her life. Jezebel is, in fact, meeting her impending death with dignity.

When Jehu arrives, he tells those with Jezebel to throw her out the window. When she hits the ground, Jehu’s horses trample her, and then Jehu and his troops enter the palace to eat. When they return to bury Jezebel, however, they find only her head, hands, and feet, because dogs have eaten her — just as Elijah had prophesied for her sin in killing Naboth.

Jehu’s usurpation is not secure until he can eliminate all of Ahab’s relatives and supporters, which he does in short shrift by beheading them. If you’re disturbed by all this bloodshed, you aren’t alone. The biblical prophet Hosea later condemns Jehu’s slaughter as excessive (Hosea 1:4).

Jehu does not confine his purge of the corruption in Israel to only the political realm. One day he calls all the priests of Baal together for a major celebration. When they are all gathered in the temple of Baal, Jehu declares, “Let’s have a sacrifice to Baal!” At this, Jehu’s soldiers come rushing in and slaughter the priests and Baal’s temple is destroyed. In one of our favorite passages, the Bible says, “and the ruins of the temple of Baal have been used as a latrine until this day” (2 Kings 10:27). Jehu’s reign lasts 28 years (842–814 B.C.E.), and his dynasty lasts for five generations, when his great-great-grandson, Zechariah, is assassinated in 747 B.C.E.

Cut to Judah: Athaliah, the woman who would rule Judah (2 Kings 11)

While Jehu is “cleaning house” in the north, King Ahaziah’s death in the south results in a revolt that nearly ends the Davidic dynasty. Ahaziah’s mother, Athaliah, takes the opportunity of her son’s death to kill all the male heirs to the throne, thus making herself ruler of Judah. Unknown to Athaliah, however, Ahaziah’s sister, Jehosheba, who is also the wife of the High Priest, hides one of her infant brothers in the Temple. After Athaliah rules for six years, the High Priest, Jehoida, gathers together an armed guard and brings the now 7-year-old son of Ahaziah out of the Temple, declaring him king. When Athaliah hears the commotion, she enters the Temple courts crying, “Treason! Treason!” Those are her last words. The soldiers execute her, and the young lad, Joash by name, is anointed king. Under the direction of the High Priest, Joash institutes many religious reforms. But these changes would be short lived because subsequent kings would return to the worship of other gods.

Experiencing Israel’s Destruction

Israel and Judah fight on and off during the next 100 years (between the mid-ninth and mid-eighth century B.C.E.). These conflicts reduce the stability and power of both nations, but especially Israel.

In 733 B.C.E., an Assyrian monarch named Tiglath-pileser III conquers many of Israel’s cities and, as was Assryria’s policy, deports many of its inhabitants. As a further demonstration of Assyria’s dominance, Tiglath-pileser III appoints a new king of Israel, Hoshea. But Hoshea soon makes a horrible mistake. Thinking that Egypt will provide military assistance, he rebels against Assyria. Assyria, as you may imagine, is not too happy about this and decides to make an example of Israel. Under Assyria’s next two kings — Shalmaneser V (727–722 B.C.E.) and Sargon II (722–705 B.C.E) — every major Israelite city is captured or destroyed. Then, in 721 B.C.E., the nation of Israel itself falls.

Many of Israel’s inhabitants are exiled, never to be heard from again. Because the northern kingdom of Israel consisted of ten tribes, these become known as the “Ten Lost Tribes of Israel.”

With these questions in mind, it comes as no surprise that Hezekiah, the king ruling Judah about the time of the fall of Israel, decides it’s time to follow God.

Too Little, Too Late: Judah’s Reforms

Two kings of Judah — Hezekiah (715–687 B.C.E.) and Hezekiah’s great grandson, Josiah (640–609 B.C.E.) — are hailed by the biblical authors as unrivalled for their devotion to God. However, even their pious efforts won’t be enough to save Judah.

The reforms of Hezekiah (2 Kings 18)

Hezekiah demonstrates his faithfulness toward God by destroying the alternate sites of worship in and around Jerusalem. He even destroys the bronze serpent made by Moses in the wilderness to heal the people of poisonous snake bites (Numbers 21:6–9) because it has become an object of worship. As further demonstration of Hezekiah’s heart for God, he allows the prophet Isaiah free access to the royal court to provide counsel and to inform him of God’s words and how they relate to matters of state.

However, the “trophy” the Assyrians want most on the palace wall is not Lachish, but Judah’s capital, Jerusalem.

Jerusalem on the brink of destruction

While the Assyrians are still attacking Lachish, the Assyrian king Sennacherib sends messengers to King Hezekiah to tell him to surrender or else face certain defeat and death. As Sennacherib’s general puts it, “None of the gods of the surrounding nations were able to protect them. And your god will not be able to protect you.” As we might say today, “Them are fightin’ words” — only the one who will be fighting for Hezekiah is God Himself.

When Hezekiah gets a letter from Sennacherib repeating this same threat, he goes into the Temple and spreads the letter before God. After praying and asking God to protect His own honor and reputation, the prophet Isaiah shows up with a message from God. In short, God tells Hezekiah that everything is going to be okay. God will deliver Jerusalem from the Assyrians, forcing the king to return home.

Hark the herald angels slaying: God delivers Jerusalem

According to 2 Kings 19, the night before the Assyrians attack, an angel goes through their camp and kills 185,000 soldiers. With the loss of his fighting force, Sennacherib is forced to return home. Interestingly, the Greek historian, Herodotus, writing several hundred years later, also describes the Assyrian army as being prevented from concluding their military campaign, although he ascribes it to a plague.

Manasseh’s “very bad” reign (2 Kings 21)

Hezekiah’s son, Manasseh, reigns for 45 years (from 687 to 642 B.C.E.), the longest of any king of Israel or Judah. However, he rescinds the religious reforms of his father, much to the dismay of the biblical authors. He practices sorcery and divination, as well as consults mediums. He even offers his own son as a sacrifice to a foreign god. Because of these heinous crimes, which the people willingly follow, God promises that Judah will soon be destroyed.

After Manasseh’s death, his son, Amon, becomes king, but because of his unpopular reign he is assassinated by his own officials after ruling only two years (from 641 to 640 B.C.E.). Because of his “untimely” death, Amon’s son, Josiah, is only 8 years old when he inherits the throne. Despite his youth, Josiah goes on to become one of Judah’s greatest kings.

The reforms of Josiah (2 Kings 22–23)

Josiah’s religious reforms are even more fervent than Hezekiah’s. Part of the reason Josiah’s reforms outdo his great grandfather’s is because of a remarkable discovery early in his reign.

While the priests are cleaning the Temple due to its neglect and abuse during the years of Manasseh and Amon, they find a scroll — and not just any scroll, but the Law of Moses. Based on the reforms that follow, this scroll does not seem to be the entire Law of Moses, but primarily the laws contained in the Book of Deuteronomy. When Josiah hears the scroll read, he tears his clothes as a sign of deep repentance and then initiates a series of reforms, including destroying all the foreign altars erected by his predecessors. He even goes up into the former kingdom of Israel and destroys the altar at Bethel, which was built by Jeroboam some 300 years earlier. In fact, his actions fulfill a prophecy that was spoken at the time Jeroboam originally built the altar and its golden calf. When Jeroboam was dedicating the newly completed altar, a mysterious man showed up and said,

O altar, altar. This is what the LORD says: “A son will be born to the house of David, Josiah by name, and he will sacrifice on you the priests of the high places who make offerings here, and human bones will be burned on you.”

—1 Kings 13:2

Now, three centuries later, this prophecy has come true. These and other reforms led the author of Kings to report that there was never a king like Josiah, “who turned to the LORD with all his heart and with all his soul and with all his might, according to all the Law of Moses” (2 Kings 23:25). Despite his successes, in 609 B.C.E. Josiah is killed during a battle with the Egyptians. So devastating is the loss of this righteous king to Judah, that the prophet Jeremiah writes songs lamenting his passing (2 Chronicles 35:25).

The End of an Era: The Fall of Jerusalem

Following Josiah’s death, the kingdom of Judah becomes a pawn amidst the mega-powers of Egypt and Babylon. First the Egyptian pharaoh, Neco, imprisons Josiah’s son, Jehoahaz, and places another of Josiah’s sons, Jehoiakim, on the throne as Egypt’s vassal. Egypt, however, gradually loses power as Babylon, led by its king, Nebuchadnezzar, gains strength through conquest. Eventually the Babylonian army approaches Jerusalem, and Jehoiakim, seeing the writing on the wall, switches alliances. This arrangement lasts for three years, but when Nebuchadnezzar retreats after failing in his attempt to invade Egypt, Jehoiakim rebels. In response, Nebuchadnezzar attacks Jerusalem in 598 B.C.E., and Jehoiakim dies during the struggle. Jerusalem’s days are numbered.

Judah’s last days (2 Kings 23–25:26)

Jehoiakim’s son, Jehoiachin, is only 18 years old when he ascends to the throne. However, he rules for just three months before Nebuchadnezzar besieges Jerusalem, forcing the king to surrender. Although Nebuchadnezzar spares the city from destruction, Jehoiachin, along with his family and officials, are carried off to Babylon, as are many of the treasures from the royal palace and Temple. The Bible records that at this time 10,000 captives are exiled, and “none remained, except the poorest of the land” (2 Kings 24:14). The next decade is full of famine resulting from this conflict’s devastation on the economy.

Nebuchadnezzar puts Jehoiachin’s uncle, Zedekiah, on the throne. Ultimately, however, Zedekiah revolts, and Babylon responds with a vengeance. In 587 B.C.E., the Babylonian forces besiege Jerusalem. While Jerusalem’s walls hold off the invading army for 18 months, inside the city things are falling apart as famine and starvation become widespread. Numerous atrocities occur during this period, including parents eating their own children in order to stay alive. Finally, in July of 586 B.C.E., Jerusalem’s walls are breached. Zedekiah tries to escape but is captured. As punishment for his rebellion, the Babylonians kill his children before him, and then gouge out his eyes, so that the death of his offspring is the last thing he sees. Then Zedekiah is led away in chains to Babylon.

Asking why in the face of disaster (2 Kings 25:27–30)

With the loss of their city and Temple, the Judahites are faced with the difficult question of how God could have allowed these tragedies to happen. After all, how could God let a nation that worships idols overthrow a nation that worships the living God? That, in fact, was the problem. Judah, and Israel before it, had neglected its worship of God. God had repeatedly warned both nations that if they didn’t repent of their idol worship, with its accompanying immorality and injustice, He would send them into exile. They had not changed their ways, and now judgment had come.

As the Books of Kings comes to a close, Jerusalem is destroyed, the Temple has been razed to the ground, and the prominent members of Judean society are in exile. But there is some hope at the end of 2 Kings. We are informed that King Jehoiachin, who had been taken captive in the 598 B.C.E. campaign, is now doing well. Although still Nebuchadnezzar’s prisoner, he is given a regular stipend and is allowed to dine at the king’s table.

Perhaps hope is not lost after all.

Ancient Spin Doctors: Chronicles

As two witnesses are better than one, the Books of 1 and 2 Chronicles offer a welcomed second opinion concerning the history of Israel’s monarchy.

Say that again? Chronicles recalls the past

In relation to the Books of Samuel and Kings, Chronicles spans from the last chapter of 1 Samuel (Saul’s death) to the end of 2 Kings, and then a little beyond. More specifically, whereas 2 Kings ends with the destruction of Jerusalem and its inhabitants in exile (around 560 B.C.E.), 2 Chronicles contains the later Persian edict by King Cyrus giving those exiled permission to return to their homeland (539 B.C.E.). Yet, Chronicles is not simply a retelling of Samuel and Kings; it is a reinterpretation of the monarchy for a different generation living during very different times.

The Chronicler’s point of view

The author of 1 and 2 Chronicles (originally one book in Hebrew) is creatively called by scholars “the Chronicler.” Although the author of Chronicles remains anonymous, Jewish tradition ascribes these books to Ezra, a scribe and priest who witnessed firsthand the Jews’ return to their homeland (see Chapter 12). Although many did not take the Persians up on this offer, many did, including Ezra. Now that the Israelites were back in their homeland, they needed a “new” history to give the nation a “new” perspective on its past and a “new” direction for its future.

Most notably, the Chronicler does not concern himself with showing all the peccadilloes and problems of the past. These were important for the earlier history, because its author (traditionally the prophet Jeremiah) wanted to explain why God would allow His people to be conquered and sent into exile. In short, the authors of Samuel and Kings demonstrate that God did not abandon His people, but His people abandoned Him by breaking His commandments and following after other gods. As a result, the earlier work gave us the negative portrait of the monarchy and the nation as a whole.

The Chronicler, in contrast, though wanting to emphasize the importance of following God’s commands, does not want to wallow in the past. Israel has been given a new beginning, a new chance to get it right, and in keeping with this new perspective, the Chronicler puts a new spin on Israel’s past.

The Chronicler spends a great deal of time and effort praising David and Solomon. For example, Chronicles makes no reference to David’s affair with Bathsheba, or Solomon’s violent ascent to the throne.

The Chronicler spends a great deal of time and effort praising David and Solomon. For example, Chronicles makes no reference to David’s affair with Bathsheba, or Solomon’s violent ascent to the throne.

As a priest, the Chronicler emphasizes the centrality of the Temple as God’s chosen place of worship.

As a priest, the Chronicler emphasizes the centrality of the Temple as God’s chosen place of worship.

Chronicles places more of an emphasis on the importance of prophets and prophecy in the administration of the state. For the Chronicler, prophets are essential for checking the power of the monarchy.

Chronicles places more of an emphasis on the importance of prophets and prophecy in the administration of the state. For the Chronicler, prophets are essential for checking the power of the monarchy.

Finally, in keeping with the Chronicler’s desire to set a positive tone for the future, Chronicles does not belabor the nation’s past sins, but focuses on spiritual renewal and God’s forgiveness.

Finally, in keeping with the Chronicler’s desire to set a positive tone for the future, Chronicles does not belabor the nation’s past sins, but focuses on spiritual renewal and God’s forgiveness.

Thus, upon the completion of the Temple, God says to Solomon:

I have heard your prayer, and have chosen for Myself this place as a house for sacrifice. If I shut up the heavens so that there is no rain, and if I command the locust to eat the land, and if I send pestilence to My people, then if My people who are called by My name humble themselves, and pray and seek My face, and turn from their evil ways, then I will hear from heaven, and I will forgive their sin and heal their land. Now My eyes will be open and My ears listening to the prayer that is made in this place.

—2 Chronicles 7:12–15