Chapter 18

From Birth to Baptism: Jesus Prepares for the Ministry (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John)

In This Chapter

Understanding the differences between the New Testament gospels

Understanding the differences between the New Testament gospels

Pondering the significance of Jesus’ birth

Pondering the significance of Jesus’ birth

Reliving Jesus’ youth and early adulthood

Reliving Jesus’ youth and early adulthood

Getting dunked with Jesus by John the Baptist

Getting dunked with Jesus by John the Baptist

Being tempted by the Devil

Being tempted by the Devil

T he narratives surrounding Jesus’ birth have inspired countless works of art and music over the centuries, including those familiar carols that echo in churches and shopping malls during Christmas time. From “Angels We Have Heard on High” to “We Three Kings,” Jesus’ birth has come to embody the simple, yet profound, message of Christmas, which is: Shop until you drop. (No, wait, that’s a later message.) The message of Christmas is: God’s Son came to earth as a little baby to save humankind.

Less well known, although no less important, are the events of Jesus’ life between his birth and the beginning of his ministry around the age of 30.

In this chapter you relive Jesus’ early years — from his birth in the little town of Bethlehem to his baptism as an adult — in order to understand why he had such an impact on his world . . . and ultimately on ours.

Examining Our Sources for Jesus’ Life

Although writings outside the Bible talk about Jesus (see the sidebar, “Other sources for Jesus’ life,” in this chapter), scholars have long considered the four New Testament gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John to be our most important sources for understanding Jesus’ life and teachings.

Other sources for Jesus’ life and teachings

Several authors from the first and early second centuries C.E. mention Jesus, providing important confirmation for the general outline of Jesus’ life. The Roman historian, Tacitus (around 120 C.E.), for example, refers to Jesus’ being crucified under Pontius Pilate, and testifies to the existence of Jesus’ followers in many parts of the Roman Empire. In addition, the Jewish historian, Josephus (around 85 C.E.), mentions Jesus’ profound teaching and ability to perform miracles, and even reports the tradition that Jesus appeared to his disciples after his death.

In addition to these Roman and Jewish historical sources, other gospels of Jesus’ life also exist. There is, for example, The Gospel of Thomas (reputedly written by Jesus’ disciple by that name; see Chapter 19), which contains supposed sayings of Jesus, many of which are not found in the four New Testament gospels. The early Christian community ultimately rejected The Gospel of Thomas as a forgery because it was (rightly) thought to have been written long after Thomas’s life, and because it promotes a belief system known as Gnosticism (see Chapter 22). Another gospel attributed to Thomas, although written several centuries later, is called The Infancy Gospel of Thomas, which relays additional stories about Jesus’ youth. In these stories, Jesus comes across as a wonderworking Dennis the Menace, even striking dead a neighborhood boy for annoying him. (Don’t worry, Jesus brings the boy back to life when his father complains.)

Even before the discovery of these other gospels, scholars had long hypothesized that the New Testament gospel writers used a common source to reconstruct Jesus’ life. This document scholars call Q from the German word Quelle, meaning “source.” According to the most prevalent theory involving Q, Matthew and Luke used Mark and Q to construct their gospels. Although Q is a hypothetical document, the existence of works like The Gospel of Thomas make its existence a theoretical possibility, and sometimes it is the best explanation for the exact grammatical and structural parallels among the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke). Of course, the Christian community has long acknowledged that the gospel writers had a common source for the life of Jesus: the life of Jesus.

Meeting the gospel writers

The New Testament gospels are ascribed to early leaders within Christianity. Matthew and John, for example, belonged to the inner circle of Jesus’ closest followers, also called the twelve disciples (see Chapter 19). Mark and Luke, although not among “The Twelve” (as the disciples are sometimes called), were traveling companions of the apostle Paul, who was arguably the most influential Christian of the first century C.E. (see Chapter 21). In addition, tradition holds that Mark knew Jesus personally, even being present when Jesus was arrested just prior to his crucifixion (see Chapter 19).

Understanding the similarities and differences among the gospels

Matthew depicts Jesus as “the Fulfillment of the Law and the Prophets.” That is, Matthew seeks to demonstrate that, far from being a break from the Jewish faith, Jesus’ life and teachings were consistent with, and even brought completion to, the Hebrew Bible’s message. Therefore, look for Matthew to include more prophecies than the other gospels, as well as to present Jesus as a kind of new Moses and perfect Israel.

Matthew depicts Jesus as “the Fulfillment of the Law and the Prophets.” That is, Matthew seeks to demonstrate that, far from being a break from the Jewish faith, Jesus’ life and teachings were consistent with, and even brought completion to, the Hebrew Bible’s message. Therefore, look for Matthew to include more prophecies than the other gospels, as well as to present Jesus as a kind of new Moses and perfect Israel.

Mark portrays Jesus as “the Suffering Son of God.” In particular, Mark attempts to show that, although Jesus should have been received with honor as God’s Son, he was destined to die a humiliating death to pay for humankind’s wrongdoing. Therefore, look for Mark to emphasize that Jesus was often misunderstood, and that Jesus wanted to keep his identity as God’s Son a secret to those who didn’t believe in him.

Mark portrays Jesus as “the Suffering Son of God.” In particular, Mark attempts to show that, although Jesus should have been received with honor as God’s Son, he was destined to die a humiliating death to pay for humankind’s wrongdoing. Therefore, look for Mark to emphasize that Jesus was often misunderstood, and that Jesus wanted to keep his identity as God’s Son a secret to those who didn’t believe in him.

Luke presents Jesus as “the Savior of the World.” That is, according to Luke, Jesus’ life and teachings were for everyone — Jew or non-Jew, rich or poor, male or female. Therefore, look for Luke to include more stories about Jesus interacting with outsiders, the poor, and women.

Luke presents Jesus as “the Savior of the World.” That is, according to Luke, Jesus’ life and teachings were for everyone — Jew or non-Jew, rich or poor, male or female. Therefore, look for Luke to include more stories about Jesus interacting with outsiders, the poor, and women.

John portrays Jesus as “the Eternal One from Heaven.” In other words, John underscores Jesus’ eternal existence and divine nature. Therefore, look for John to be more theological and philosophical than the others.

John portrays Jesus as “the Eternal One from Heaven.” In other words, John underscores Jesus’ eternal existence and divine nature. Therefore, look for John to be more theological and philosophical than the others.

In the Beginning: Contemplating Jesus’ Very Early Life (John 1)

According to the Gospel of John, Jesus’ story properly begins “In the beginning,” before God created anything. In fact, the opening words from John’s gospel come directly from the opening words of the first book of the Bible, Genesis. But rather than follow these words with a description of Creation (as Genesis does), John lingers for a moment in order to explain that Jesus was not only with God in the beginning, Jesus was (and is) God (John 1:1).

John’s opening description of Jesus highlights two related themes of his gospel: Jesus’ eternal existence and his divine nature. Yet, John’s words also raise an important theological question: How can God and Jesus both be God? This question is further complicated (or clarified, depending on your perspective) by passages that similarly equate God’s Spirit with God (see, for example, 2 Corinthians 3:17).

Whether one believes in the Trinity or not, that’s quite a story.

Reliving the Christmas Story

Receiving Jesus’ birth announcement (Matthew 1 and Luke 1:26–38)

According to the gospels, Jesus’ mother is a young woman named Mary. Although being of humble means, Mary and her fiancé, Joseph, are of noble birth, as they are descendants of the great Israelite king, David (see Chapter 9). This connection to David is important for the New Testament writers, because many Jews during Jesus’ time were expecting a Davidic Messiah or king who would deliver them from their enemies (the Romans, during Jesus’ day).

But there is something else about Mary that is exceptional — something that she’s not even aware of at first. She is to become pregnant with Jesus while she is still a virgin. Mary finds out about her unusual pregnancy when she is visited by the angel Gabriel, who declares:

The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you. Therefore, the Holy One who is conceived in you will be called the Son of God.

—Luke 1:35

Revisiting the manger scene: Jesus’ birth (Luke 2:1–20)

As Mary approaches her due date, a most “unfortunate” thing happens. According to Luke, the Roman Emperor, Caesar Augustus, decrees that a census should be taken of everyone in his empire. In order to accomplish this, people have to go to their ancestral hometown in order to register their names.

O little town of Bethlehem

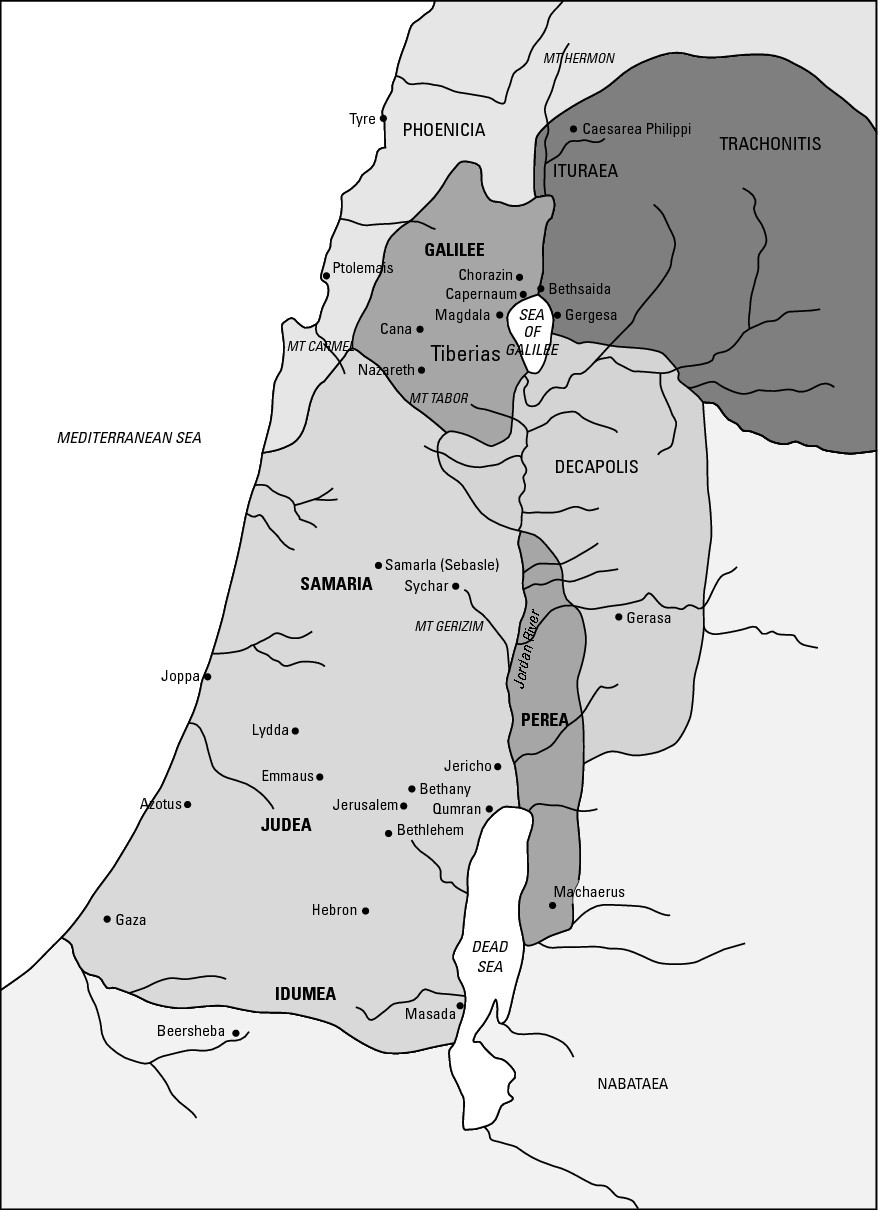

Because Joseph and Mary trace their lineage to King David, Augustus’ decree requires that they make the approximately 80-mile trek from their home in Nazareth to David’s hometown of Bethlehem (see Figure 18-1). Yet, this inconvenience is important, because it further connects Jesus’ life with the expectations of a coming Davidic Messiah. As the angel Gabriel says to Mary:

The Lord God will give [Jesus] the throne of his ancestor David, and he will reign over the house of Jacob forever. And his kingdom will never end.

—Luke 1:32–33

|

Figure 18-1: Map of Israel during Jesus’ life showing the Roman divisions used for administrative purposes. |

|

Away in a manger

Upon arriving in Bethlehem, Mary and Joseph cannot find lodging at the inn. Therefore, they are compelled to stay in an animal stable. Here Mary gives birth to Jesus, and places him in a manger (a feeding trough). At least this is how the story has traditionally been understood — but this may be wrong.

Today The Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem commemorates the place of Jesus’ birth.

Angels we have heard on high

In keeping with Luke’s emphasis on Jesus as the Savior of the whole world, including the poor and seemingly unimportant, he recounts that, upon Jesus’ birth, an angel appears to some lowly shepherds in a nearby field, and says,

Behold! I bring you good news of great joy that will be for all people. For today in the city of David is born to you a Savior who is Christ the Lord.

—Luke 2:10–11

In this brief announcement, the angel says a lot. Not only does he mention the “good news” or gospel that will be for “all people,” he also refers to the messianic expectation surrounding a descendant of David. The angel then tells the shepherds that they will find this Messiah “wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger.” Suddenly, numerous angels appear in the sky, and begin declaring (not “sweetly singing”) praise to God.

Today, outside of Bethlehem, is a low-lying valley called The Shepherds’ Field, which marks the traditional location of this event.

The adoration of the shepherds

Quickly, the shepherds make their way to Bethlehem, where they find the infant child and worship him. Mary, who is amazed at hearing the report of the angel’s announcement, “treasured all these things, pondering them in her heart.” The shepherds then go back to their flocks, but not without telling everyone they encounter about the amazing things they had seen and heard.

Calculating the date of Jesus’ birth

We do not know the exact date or year of Jesus’ birth. The determination of B.C. (“before Christ”) and A.D. (anno Domini or “year of our Lord”) was calculated in the sixth century, and the scholar who did it, Dionysius Exiguus, missed by a few years (though he came remarkably close). Most scholars place Jesus’ birth around 6 or 5 B.C., because both Matthew and Luke say that Herod the Great, the Roman appointed ruler, was alive when Jesus was born (Herod died in 4 B.C.). (For the choice of December 25 as Jesus’ birthday, see Chapter 27.)

Jesus’ circumcision and dedication (Luke 2:21–40)

Eight days after his birth, Jesus is circumcised (ouch). This fulfills God’s command as expressed to Abraham (Genesis 17) and Moses (Exodus 12) in the Hebrew Bible. Jesus is also given his name at this time, a tradition that similarly derives from Abraham, who circumcised and named his son, Isaac, at 8 days old (Genesis 21).

Further underscoring Jesus’ “Jewishness” is that, at 40 days old, he is brought to the Temple to be dedicated to God. This rite finds its origins in the Hebrew Bible, where, according to the Law of Moses (see Chapter 7), all firstborn sons are to be dedicated to God by sacrificing a lamb and a turtledove or pigeon. If you could not afford a lamb, you could sacrifice an additional bird.

Following these events, the gospel of Luke says that Mary, Joseph, and Jesus returned to Nazareth, where Jesus grew up.

“Now wait just a minute here!” you may be saying. “You skipped the part about the three wise men who worshiped Jesus alongside the shepherds and presented him with gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh! How could you forget something like that?” Actually, we didn’t. We explain their absence (actually tardiness) from Jesus’ birth story in the following section.

Adoration of the magi (Matthew 2:1–12)

No manger scene would be complete without the presence of the wise men (or magi, as they are sometimes called) bearing gifts of gold, frankincense (or incense), and myrrh for the newborn Jesus. There’s only one problem: The wise men most likely weren’t there.

The mysterious absence of the magi at Jesus’ birth

As we’ve already noted, Luke wants to show that Jesus is the Savior of everyone, whether Jew or gentile, male or female, rich or poor. Therefore, Luke tells us about the lowly shepherds who come and worship Jesus, but says nothing about the wise men.

Matthew, though not disagreeing with Luke’s emphasis, wants to present Jesus as the fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies concerning the Messiah. Because the Messiah was to be a descendant of David, the great king of Israel, Matthew emphasizes Jesus’ royal origins by recounting the story of the wise men, who are royal astrologers who have followed a star that heralds the birth of a king in order to present him with royal gifts. It’s hard to miss the point.

Yet, Matthew does not seem to present these wise men as arriving at Jesus’ birth, but perhaps as much as two years later (see the section “Out of Egypt,” later in this chapter). That is, even if we combine the accounts of Matthew and Luke, it probably would be inaccurate to place the shepherds and magi side by side. (So the next time you’re at a friend’s house at Christmastime, we recommend that you tactfully remove the wise men from the manger scene.)

The magi eventually make their way to Jerusalem to ask King Herod, the Roman appointed ruler of the Jews (see the sidebar “Meeting Herod the Great” in this chapter), where the king of the Jews has been born. Herod, as you might imagine, is not too happy to hear about this rival claimant to the throne, even if that rival may still be in diapers. When Herod’s officials inform him that the Messiah is suppose to be born in Bethlehem, Herod passes this information on to the wise men, and he asks them to return with news of the child’s exact whereabouts so he can also worship (read: kill) him.

The Slaughter of the Innocents

The wise men continue on their way to Bethlehem, where they find Jesus. However, after they present their gifts to Jesus, they are warned in a dream not to return to Herod because he only intends to kill this newborn king. When Herod finds out that the wise men have left his territory without reporting back to him, he becomes furious and dispatches his soldiers to kill all male children in the vicinity of Bethlehem who are 2 years old and younger — a choice informed by the time told him by the wise men, which suggests that Jesus is approaching 2 years old when the wise men appear. Although Jesus escapes Herod’s henchman unharmed (Joseph had been warned in a dream to flee to Egypt) many youngsters do not. Herod’s murderous act is often referred to as “The Slaughter of the Innocents.”

Meeting Herod the Great

Herod the Great (so named due to his long and illustrious reign) and his descendants play an important role throughout the New Testament, so it’s important that we introduce you to him.

Herod was appointed King of the Jews by the Romans, who during this period ruled over what was once ancient Israel. Although a convert to Judaism, Herod was an Idumean (descendants of the Edomites, who had been longtime enemies of Israel). Therefore, many Jews did not consider Herod to be a legitimate King of the Jews. Despite not having the right pedigree, Herod was a fairly capable ruler. He was so capable, in fact, that he remained King of the Jews from 37 B.C.E. until his death in 4 B.C.E., and afterward his descendants ruled over parts of Judea until 70 C.E., when the Romans destroyed Jerusalem in response to the Jewish Revolt (66–72 C.E.). Yet, perhaps Herod’s greatest achievement was his complete renovation of the Jerusalem Temple, which he transformed into one of the most beautiful structures in the ancient world.

Despite Herod’s many accomplishments, his reign also had its share of, let us say, indiscretions. For example, early in his rule, he executed many members of the Jewish Council of Elders (a group known as the Sanhedrin) for their support of his rivals: the Hasmoneans, a Jewish family who had long ruled over Israel (see Chapter 16). In an attempt to legitimize his rule in the eyes of the people, Herod eventually married the Hasmonean princess, Mariamme. This did little to win the people’s (or Mariamme’s) affections, a situation that was only aggravated when he killed Mariamme on suspicion of adultery — a decision he later regretted and one that plagued him for the rest of his life. Herod then killed his mother-in-law (put that thought out of your mind), because she was plotting with Cleopatra of Egypt (yes, the Cleopatra of Egypt) to avenge her daughter’s death and to appoint one of her own grandsons as the new king. Even after killing his mother-in-law, Herod feared that his two sons might seek revenge for their mother’s death and take his throne; so he killed them as well. As the Roman emperor, Caesar Augustus, is reputed to have said, “I would rather be Herod’s pig than his son.” It is into this political and religious climate that another King of the Jews would be born, and Herod would try to kill him, too.

Out of Egypt (Matthew 2:13–23)

Matthew reports that Jesus and his parents remain in Egypt until Herod’s death in 4 B.C.E., after which they set out for their home. Yet, while on their way, Joseph receives word that Herod’s son, Archelaus, is now ruler in Judea. Fearing that Archelaus may be seeking Jesus’ life, Joseph decides to take his family to Nazareth (refer to Figure 18-1). According to Matthew, Jesus’ journey to Egypt and his subsequent relocation to Nazareth fulfills two prophecies relating to the Messiah:

God would call His son “out of Egypt” (Hosea 11:1) — a notice that originally referred to Israel’s exodus from Egypt.

God would call His son “out of Egypt” (Hosea 11:1) — a notice that originally referred to Israel’s exodus from Egypt.

The Messiah “would be called a Nazarene.” It’s unclear where this prophecy comes from. Most scholars think it refers to Isaiah 11:1, which predicts the coming of “a sprout (Hebrew: nezer) from the stump of Jesse.” Because Jesse is David’s father, this passage predicts the coming of a Davidic Messiah who would establish a kingdom of everlasting righteousness and peace. Jesus, then, is the promised “little sprout.”

The Messiah “would be called a Nazarene.” It’s unclear where this prophecy comes from. Most scholars think it refers to Isaiah 11:1, which predicts the coming of “a sprout (Hebrew: nezer) from the stump of Jesse.” Because Jesse is David’s father, this passage predicts the coming of a Davidic Messiah who would establish a kingdom of everlasting righteousness and peace. Jesus, then, is the promised “little sprout.”

Thus, Joseph, Mary, and Jesus settle in Nazareth.

Growing Up with Jesus

The New Testament provides very little information about Jesus’ youth, requiring us to fill in the details from what we know about growing up in first-century Palestine.

Living in Nazareth (Luke 2:39–40)

Nazareth, Jesus’ hometown, was a small village in the foothills of Galilee (refer to Figure 18-1). With a total population of no more than 500 people, Nazareth was like many small towns both then and now: Everybody knew everybody. If you grew up in a small town, then you know this has both its advantages and its disadvantages. As a demonstration of the latter, when Jesus impresses his hometown with his amazing teaching and miracles, they ask in apparent derision, “Is this not the carpenter’s son?” As Jesus later retorts, “A prophet is never welcome in his hometown” (Luke 4:24).

Yes, we said Joseph & Sons (plural). Jesus is said to have had four brothers and at least two sisters. Later Catholic doctrine, however, would contend that these were not actual brothers and sisters, because Mary remained a virgin even after Jesus’ birth — a doctrine known as “The Perpetual Virginity of Mary.” Although the New Testament never says that Mary was a perpetual virgin, in defense of this doctrine, the Greek word used for brothers and sisters can also mean close relatives, or even friends or affiliates. Yet, suggesting that these are actual siblings (that is, born of Mary and Joseph, and therefore really Jesus’ half brothers and sisters) is Matthew’s notice that Joseph did not have sexual relations with Mary “until Jesus was born.” “Until” is a strange word to use if Joseph never had relations with Mary.

Traveling to Jerusalem (Luke 2:41–52)

The gospel of Luke says that when Jesus is 12 years old, his family and relatives go to Jerusalem for their annual celebration of the Passover — a feast commemorating Israel’s deliverance from Egyptian slavery (see Chapter 27). After the week-long festivities, Jesus’ family packs up their belongings and begins the long journey home. After the first day of travel, Mary and Joseph realize that Jesus isn’t with them. Now before you call the ACPS (Ancient Child Protection Service), it is important to keep in mind that Joseph and Mary are traveling with their extended family, and they probably assume that Jesus is with one of his cousins’ families.

Mary and Joseph hurry back to Jerusalem and, after three days of searching, they finally find Jesus at the Temple, listening to and questioning the Jewish priests and religious authorities. Jesus shows such insight, in fact, that “everyone was amazed at his great understanding” (Luke 2:47). Mary and Joseph are more annoyed than amazed, and Mary asks, “Why have you done this to us? Your father and I have been anxiously looking for you everywhere!” Unflustered, Jesus responds, “Why were you looking for me? Didn’t you know that I had to be in my Father’s House?” (Luke 2:49).

The “Lost Years” of Jesus

From the time Jesus is 12 to the time he begins his public ministry (about 18 years later) nothing is recorded about Jesus’ life except that he “grew in wisdom and in stature, and in favor with God and people” (Luke 2:52). Some scholars call this period the “Lost Years” of Jesus and have proposed all kinds of imaginative activities for Jesus during this time, including studying philosophy in Greece, Buddhism in China, Hinduism in India, and Native American religion in the Americas. Although the intent of these theories is admirable (explaining how someone from the “backwaters” of the Roman Empire could captivate the world with his profound teaching and exemplary life), the theories themselves are, well, quite imaginative.

As with many figures of antiquity, much of Jesus’ early life is lost to us. But what he accomplished in the few short years recorded of his adulthood, was enough to change the world.

Witnessing Jesus’ Baptism

When we encounter Jesus again, Luke tells us he is “about 30 years old” and on the verge of undergoing a religious rite known as baptism (a ritual washing by immersion in water) at the hands of a man named John the Baptist.

John the Baptist is an interesting character. He hangs out in the wilderness, eats bugs and wild honey, wears camel-hair jackets (okay, actually just camel-hair garments), and tells people to prepare themselves for God’s coming kingdom. Then, as an expression of people’s readiness, he dunks them in water. So, who is this guy? And why is he doing this?

Getting to know John the Baptist (Luke 1:5–23, 39–80)

John the Baptist belongs to the priestly class of Israel, and, like Jesus, is born under miraculous circumstances. One day, while John’s father, Zechariah, is serving at the Jerusalem Temple, Gabriel appears to him and announces that, although Zechariah’s wife, Elizabeth, is barren, God is going to give them a son who will prepare the way for the Messiah (God’s appointed deliverer for the Jews). Zechariah is dumbfounded — literally. Because he doesn’t believe Gabriel, Gabriel makes him “dumb” or mute until John is born.

After John’s birth narrative, Luke simply reports, “And the child grew and became strong in spirit, and lived in the wilderness until he became manifest to Israel” (Luke 1:80).

Undergoing baptism with Jesus (Matthew 3; Mark 1; Luke 3; John 1)

When the gospels reintroduce you to John the Baptist, he is already an adult and attracting large crowds in the desert with his preaching and baptizing. According to the gospel writers, John’s activity fulfills two predictions made long ago by the prophets Malachi and Isaiah (see Chapter 13). Quoting from both prophets (although only mentioning Isaiah), Mark writes,

I will send my messenger before you to prepare your way. A voice calling in the wilderness, “Prepare the way for the LORD, make straight His paths.”

—Mark 1:2–3

It is into this context that Jesus approaches John to be baptized.

As Jesus comes up from the water, the heavens open and the Spirit of God descends upon him in the form of a dove. Then, as though this isn’t remarkable enough, a voice from heaven declares, “This is My beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased.” With this affirmation, Jesus is now ready to meet the forces of darkness and begin his ministry.

Experiencing Jesus’ Temptation

Following Jesus’ baptism, he goes into the desert where he fasts for 40 days.

While in the wilderness, Satan comes to Jesus in order to tempt him. (In what form Satan comes the Bible, profoundly, doesn’t specify.) Satan presents three temptations to Jesus, each of which touches on a universal desire or concern of the human spirit:

Provision: Satan tells Jesus to turn stones into bread.

Provision: Satan tells Jesus to turn stones into bread.

Protection: Satan tells Jesus to jump off the pinnacle of Jerusalem’s Temple because, if he is the Son of God, God will protect him.

Protection: Satan tells Jesus to jump off the pinnacle of Jerusalem’s Temple because, if he is the Son of God, God will protect him.

Power: Satan tells Jesus to worship him, and he will give Jesus all the kingdoms of the world.

Power: Satan tells Jesus to worship him, and he will give Jesus all the kingdoms of the world.

Interestingly, Jesus responds to each of Satan’s temptations with a passage from the Bible, which intends to underscore the importance of using the truth in combating evil. Satan, however, can play the Quote the Bible game, too. When he challenges Jesus to jump off the pinnacle of the Temple, for example, Satan notes that God’s angels will “bear you up so that you don’t strike your foot against a stone” (Psalm 91:11–12).

As with the other temptations, Jesus retorts with the proper use of God’s word: “You shall not test the LORD your God” (Deuteronomy 6:16). And with this said, Satan departs.

Having successfully repelled the forces of evil, Jesus leaves the wilderness to begin his ministry of preaching and miracle working — a ministry that, although brief, still impacts us today (see Chapter 19).

John the Baptist’s latter days

After baptizing Jesus, John’s popularity began to wane as more and more people followed Jesus. John’s response to this circumstance reveals his humility, as well as the preparatory nature of his ministry of baptizing and teaching: “He must increase, while I must decrease” (John 3:30). Notwithstanding John’s humility, Jesus describes John as “the greatest of those born of women” and “more than a prophet.”

Eventually John was imprisoned and executed by Herod Antipas, the son of Herod the Great, for confronting him for marrying his own brother’s wife (Matthew 14:3-12). Interestingly, the first century C.E. Jewish historian, Josephus, also records these events and, similar to the New Testament, describes John as a “good man, who commanded the Jews to do what’s right, both towards one another and towards God” (Antiquities of the Jews 18.5.2).