Chapter 21

The Traveling Salesman of Tarsus: Paul’s Life and Letters

In This Chapter

Witnessing Paul’s transformation from Christian persecutor to persecuted Christian

Witnessing Paul’s transformation from Christian persecutor to persecuted Christian

Traveling with Paul around the Mediterranean on his missionary journeys

Traveling with Paul around the Mediterranean on his missionary journeys

Reading (and understanding) Paul’s letters

Reading (and understanding) Paul’s letters

C hristianity’s spread “to the uttermost parts of the world” was due in large part to a man named Paul. This is extraordinary since when we first meet Paul he is vigorously persecuting Christians in order to stop this “heresy” from spreading. Then, unexpectedly, he changes from the movement’s chief persecutor to its chief proponent, and through his influential missionary journeys and letter writing Christianity is transformed from a Jewish sect into a worldwide movement. In this chapter, you explore Paul’s life and writings to see what about him made such an impact on his world . . . and ours.

From Persecutor to Persecuted: Paul’s Transformation

When we first encounter Paul (or “Saul,” as he is first called; see “Paul’s First Missionary Journey” later in this chapter for why his name is changed), he’s at the execution of Christianity’s first martyr, Stephen:

[Stephen’s accusers] rushed at him and dragged him out of the city, where they began to stone him. Those present laid their garments at the feet of a young man named Saul . . . and Saul was giving approval to Stephen’s death.

—Acts 7:57-58; 8:1

The act of laying garments at another’s feet is a sign of honor and indicates that Paul is overseeing not the coatroom but Stephen’s execution. Confirming this are Paul’s actions following Stephen’s death:

Saul set out to destroy the church, going from house to house, where he dragged men and women off to prison.

—Acts 8:3

Eventually Paul heads toward Damascus, a leading city of the eastern Roman Empire, to arrest the followers of “this Way,” as Christianity is first called (its followers aren’t called Christians until around 40 C.E. — see Acts 11:26). On the way, he has a life-changing experience.

Paul’s life before his conversion

Paul was born in Tarsus, a city in eastern Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) and one of the intellectual centers of the Roman Empire. Though Jewish, Paul was also a Roman citizen, a status that afforded him tremendous rights and privileges, including the right to trial before being tortured or imprisoned, as well as the right to appeal “lower court” decisions to the highest court in the Empire: the emperor himself.

Although born in Tarsus, Paul was raised and educated in Jerusalem, where he studied under the leading rabbi of his day: Gamaliel. As an indication of Gamaliel’s influence, in the book of Acts he talks his colleagues out of executing Christians. Paul, however, didn’t share his teacher’s moderate views. As Paul describes it: “I put many [Christians] in prison, and when they were put to death, I cast my vote against them” (Acts 26:10). With similar zeal, Paul gained the respect of his contemporaries. Yet, while climbing this ladder of success, the ladder toppled, and Paul was never the same.

A Damascus Road experience: Paul’s conversion and commission (Acts 9:1–19)

We say someone has had a “Damascus Road experience” when an event completely changes his or her perspective on life. Paul has one of these. In fact, he has the first and most dramatic of all Damascus Road experiences.

As Paul and his companions approach Damascus to apprehend Christians, a blinding light surrounds them and Paul falls to the ground. He then hears a voice: “Saul, Saul, why are you persecuting me?” (Acts 9:4). “Who are you, Lord?” Paul asks. The voice replies, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting.” This answer would have been more shocking than the phenomena surrounding it, since Paul believed he was defending God in his efforts to stamp out the movement founded on Jesus’ life and teachings. Here Jesus says that his efforts are accomplishing the exact opposite. When the light departs, Paul, now blind, is led by his companions into Damascus.

In Damascus, Paul has a vision that a man named Ananias will heal him of his blindness and tell him what to do next. Meanwhile, in another part of town, Ananias receives a similar vision in which God tells him to find Paul and lay his hands on him to restore his sight. Ananias, a Christian, protests, saying he has heard about Paul and his efforts to arrest Christians. God’s response both allays Ananias’ fears and informs him (and the reader) of Paul’s future:

Go! This man is My chosen instrument to bear My name to the Gentiles and their kings, and the people of Israel. I will show him how much he must suffer for My name.

—Acts 9:15–16

Ananias does as God commands, healing Paul “in the name of Jesus.” Paul is then baptized as a sign of his identification with this new movement.

Man on the run: Paul escapes Damascus and Jerusalem (Acts 9:20–31)

Paul soon begins preaching in the synagogues of Damascus that “Jesus is the Son of God.” The people are shocked: “Was this not the man who raised trouble in Jerusalem for those who called on this name?” Shock soon turns to anger, as many believe Paul is committing blasphemy (speaking falsehoods about God). Some even conspire to kill Paul, and a 24-hour watch is posted at the city gates to ensure that he doesn’t escape the city. With his life in danger, some Christians lower Paul in a basket from the city wall at night.

Paul eventually makes his way to Jerusalem, where he presents himself to the church leaders as a recent convert. However, they think Paul’s supposed conversion is a trick to gain information in his efforts to destroy the church. One disciple, though, is willing to take a chance on Paul. His name is Barnabas, a name that, appropriately enough, means “son of encouragement.” Barnabas eventually convinces the apostles that Paul’s conversion is genuine, and Paul, the one-time persecutor of the church, is now accepted as a member.

Once word gets out that Paul has become a follower of “this Way,” his former allies become his enemies and he is forced to flee Jerusalem. This is only the beginning of Paul’s troubles. Throughout his three-decades- long adventure as a representative of Christianity, he experiences many other close calls. In one of his letters, he tells of the many trials he has endured:

Five times I received from the Jews the forty lashes minus one. Three times I was beaten with rods. Once I received a stoning. Three times I was shipwrecked; for a night and a day I was adrift at sea; on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, from bandits, from my own people, from Gentiles, in the city, in the wilderness, at sea, from false brothers and sisters; in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, hungry and thirsty, often without food, cold and naked. And, besides other things, I am under daily pressure because of my anxiety for all the churches.

—2 Corinthians 11:24–28

Paul certainly did learn how much he must suffer for the sake of Christianity.

I Get Around: Paul’s Missionary Journeys

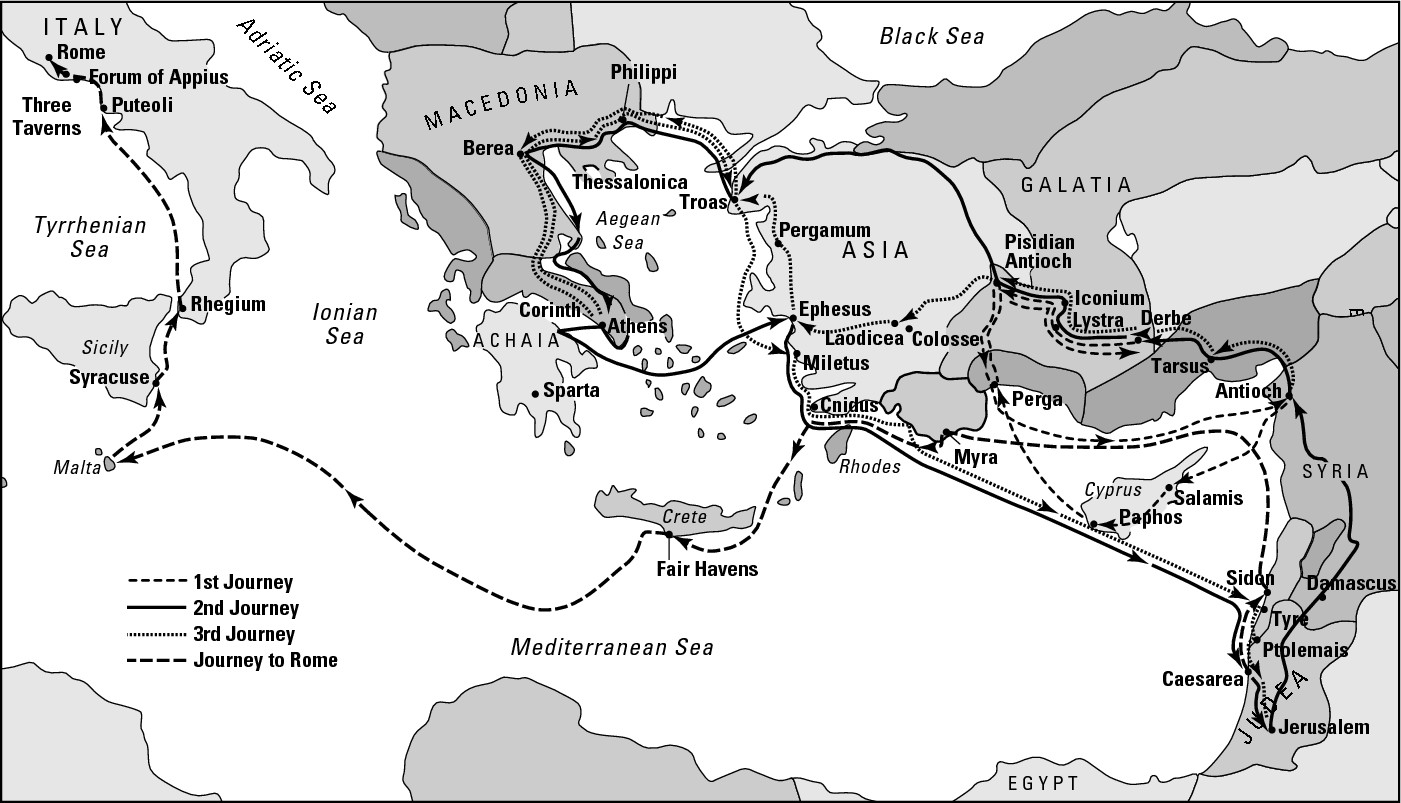

The context for much of Paul’s suffering is his several missionary journeys. On these journeys, Paul travels extensively throughout the Mediterranean region, including Syria-Palestine (modern-day Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, and parts of Jordan), Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), Macedonia (modern-day Bulgaria and Yugoslavia), Greece, Italy, and perhaps as far as Spain (see Figure 21-1). As he travels, Paul preaches to both Jews and Gentiles, starts new churches, visits existing churches, and writes numerous letters that now make up nearly half of the New Testament.

To help you understand the impact of Paul’s journeys on what was still a fledgling movement at his conversion, we follow his travels in this section, highlighting a few of the episodes that characterize Paul’s energy and sincerity in his efforts to spread the “good news” of Christianity.

|

Figure 21-1: A map of Paul’s travels throughout the Mediterranean to spread Christianity. |

|

Paul’s first missionary journey (46–49 C.E.)

Paul’s first missionary journey, recorded in Acts 13 and 14, takes place about 10 to 12 years after his conversion. Between his conversion and his first journey, Paul spends time in a number of places, including Arabia (not Saudi Arabia, but an area roughly corresponding to southwestern Jordan and southern Israel), Jerusalem, Tarsus (Paul’s hometown), and Syrian Antioch, the third largest city of the Roman Empire (after Rome and Alexandria). While in Antioch, Paul, Barnabas, and Barnabas’ nephew, John Mark (the person credited with writing the second gospel) are “called apart by the Holy Spirit” to preach the gospel. This begins Paul’s first missionary journey.

Paul’s name change: Paul and company go to Cyprus (Acts 13)

On this journey, Paul and his companions sail first to the island of Cyprus (reputedly Barnabas’ home), where Paul meets his first gentile (non-Jewish) convert, who is named Paulus. Interestingly, prior to this event, the book of Acts refers to Paul by his Semitic name: Saul. After this event, Acts begins calling him Paul — in apparent recognition of Paul’s initiation into the gentile ministry that would characterize his life. From Cyprus, Paul, Barnabas, and Mark sail on to the southern coast of Asia Minor, where Mark is said to have left them for home. Paul and Barnabas then continue on to central Asia Minor, where, in the city of Lystra, they have a very strange experience.

The gods must be crazy: Paul and Barnabas in Lystra (Acts 14)

Lystra was a Roman colony founded in 26 B.C.E. by Caesar Augustus, who settled it with veterans of the Roman army. In other words, Lystra had a largely gentile population who worshiped the full entourage of Greco-Roman gods. Thus, when Paul heals a crippled man there, the people mistake him and Barnabas for gods. Because Paul is the chief spokesperson of the two, the people think he is Hermes, the messenger god of the Greek pantheon, and identify Barnabas, the strong, silent type, with Zeus. Before Paul and Barnabas realize what is going on, the town priest is offering them sacrifices. Only with great difficulty do Paul and Barnabas persuade the city’s inhabitants that they are not gods, but mere mortals.

Although this scene may strike you as peculiar, the belief that gods periodically visited communities to test their virtue was widespread in the ancient world and is even evident in the Hebrew Bible’s account of Abraham’s three divine visitors (Genesis 18). In addition, Lystra seems to have had a tradition that it was once visited by gods who went unrecognized, except by an elderly couple who were blessed for their alertness. The inhabitants of Lystra were not going to make that mistake again.

Paul and Barnabas’ near-deification experience soon turns into a near-death experience as certain individuals opposed to their message stir up the crowds, who in turn stone Paul and drag him outside of the city, leaving him for dead. Paul’s companions also fear the worst, as he lay motionless for a long time. Suddenly, however, Paul stands up (whether by miracle or might, the Bible does not say). In keeping with his character, Paul boldly reenters the city. Eventually, Paul and Barnabas make their way back to Antioch and report to the church all that they experienced. They then continue to Jerusalem, where they participate in the church’s first council (Acts 15; see Chapter 20).

Paul’s second missionary journey (50–52 C.E.)

Paul’s second missionary journey, recorded in Acts 15:36 through 18:22, takes place shortly after the council in Jerusalem. The stated purpose of this journey is to “visit the communities of believers in all the towns where we preached the word of the Lord to see how they’re doing” (Acts 15:36). Yet Barnabas does not join Paul because they have a disagreement over whether Mark, who left them during their first journey, should come along. Paul views Mark’s departure as desertion. Barnabas, Mark’s uncle and one who takes chances on risky propositions (such as Paul earlier), wants to give Mark another chance. So sharp is their disagreement that these two friends, who had experienced so much together, part ways. Barnabas and Mark go to Cyprus, while Paul and Silas, a prophet from Jerusalem, take the inland route to revisit the churches that Paul and Barnabas founded on their first journey.

Paul picks up Timothy and Luke (Acts 16)

When in Greece . . . : Paul goes to Athens (Acts 17)

Paul eventually arrives at Athens, once the intellectual and cultural center of Greece. In Paul’s day, however, it is little more than a symbolic center of Greece’s great past. For Paul, a monotheist, Athens is anything but admirable. Noticing the innumerable idols and altars to various gods, Paul becomes agitated and begins preaching in the marketplace. Among the crowd is a respected group of philosophers, who invite Paul to be a guest lecturer at the preeminent “university” of Athens: the Areopagus.

Paul doesn’t cite the Hebrew Bible during his lecture, because doing so would have meant little to his Greek audience. Instead, he puts a positive spin on the plethora of altars that earlier provoked him to speak in the marketplace. In particular, Paul refers to an altar he saw with the inscription: “To an Unknown God.” Paul informs the crowd that the god they desire to appease by this altar is none other than “the God who made the world and everything in it” (Acts 17:24). Paul then quotes from their own philosophers who had monotheistic inclinations, including Epimenides (around 600 B.C.E.), who in his Cretica wrote, “in him (the one god) we live and move and have our being,” as well as Cleanthes (331–233 B.C.E.) and Aratus (315–240 B.C.E.), who in their Hymn to Zeus and Phaenomena, respectively, state, “we are his (the one God’s) offspring.” Paul explains that this one God intends to judge the world which He will accomplish through a man He raised from the dead.

At the mention of the resurrection, some balk (most likely the Epicureans; see the sidebar “Epicureans and Stoics” later in this chapter). Others want to hear more (most likely the Stoics). Still others believe, including Dionysius, who is a member of the Areopagus and who, according to later church tradition, would become the bishop of Athens.

After traveling through Greece, Paul and his companions eventually make their way back to Antioch, where they report the amazing things that are happening among the gentiles who are coming to faith.

Epicureans and Stoics

Among those present at Paul’s lecture on the Areopagus are representatives from two of the most influential philosophical schools of the Greco-Roman Period: Epicureanism and Stoicism.

Epicureanism was founded on the teachings of the Greek philosopher Epicurus (fourth through third centuries B.C.E.), who argued that everything was made of matter and that upon death the individual ceased to exist. The chief aim of life, then, was to avoid pain and pursue pleasure. For Epicurus, pursuing pleasure meant seeking truth through philosophical discourse and reflection. By Paul’s day, however, Epicureanism had become, at least by reputation, a philosophical front for hedonism. “Eat, drink, and be merry, for tomorrow we die,” captures the essence of their worldview.

Stoicism was founded on the teachings of Zeno, a contemporary of Epicurus who had been influenced by the teachings of Socrates. Stoics held to the existence of the eternal soul. As a consequence, Stoics believed in an afterlife and that your actions in this life would determine your eternal state. A Stoic’s central aim was to seek pietas (from which we get the word piety), which meant living a life of devotion and dedication to the gods, your country, and your family. Carnal desires, especially if allowed to override the rational mind, were the enemies of pietas and therefore stringently held in check.

Paul’s third missionary journey (54–58 C.E.)

Paul stays in Antioch less than a year before setting out on his third missionary journey. As with his second, Paul takes the land route and revisits churches throughout Asia Minor, eventually arriving at the city of Ephesus, where he, in keeping with his track record, causes trouble.

Raising a ruckus in Ephesus (Acts 19)

Paul stays in Ephesus for almost three years, speaking in its synagogues, writing letters to churches he had visited or intended to visit, and teaching in the lecture hall of a certain Tyrannus. Paul also performs numerous miracles, including healing diseases and casting out demons. Despite the positive impact of Paul’s activities on the local population, they have a negative impact on the local economy. Ephesus was a center for Artemis (Roman Diana) worship, and Paul’s preaching lessens the demand for her idols as people begin worshiping the invisible God of the Jews and Christians. In response to the idle idol economy, a silversmith named Demetrius, who “brought in no little business for the craftsmen,” instigates a riot. Soon Demetrius and his fellow craftsmen have the whole city shouting, “Great is Artemis of the Ephesians!” in the Greek theater at Ephesus (which is still standing today).

Although the rioting eventually dies down, Paul realizes that he’s probably overstayed his welcome and leaves. After visiting other churches in Asia Minor, Macedonia, and Greece, Paul heads back to Jerusalem to attend the Feast of Pentecost. This seems to have been the last feast Paul attends in Jerusalem. As Paul would say to the church leaders at Ephesus, “Everywhere I go the Holy Spirit warns me that imprisonment and hardships lay ahead of me” (Acts 20:23). And they do.

Paul’s arrest in Jerusalem (Acts 21–22)

Soon after arriving in Jerusalem and reporting to the apostles all that happened on his last journey, Paul is spotted in the Temple courts by men from Asia Minor who had opposed him there. Accusing Paul of blasphemy, a crowd soon gathers and tries to kill him. Paul’s life is saved only when the Roman commander in charge of controlling riots intervenes and takes Paul to the Antonia fortress adjacent the Temple for “questioning.” Paul is about to be beaten for instigating a riot when he asks, “Is it lawful to flog a Roman citizen without a trial?” It isn’t, so the Roman commander arranges a trial in which Paul’s accusers bring formal charges against him. As their accusations fall outside Roman concerns, the commander decides to send Paul to the Jewish legal authorities to be tried. However, he finds out from Paul’s nephew (the son of Paul’s sister, who lives in Jerusalem) that Paul’s opponents are planning to kill Paul by ambush. The commander can’t allow this to happen to a Roman citizen, so he sends Paul to Caesarea, the residence of the Roman governor, where his case could get the attention it deserved.

Paul’s imprisonment in Caesarea (Acts 23–26)

Paul stays in prison in Caesarea for two years, during which time he is required to defend himself on several occasions. Although Paul is not found guilty by the two Roman governors whose tenures overlap his imprisonment — Antonius Felix (52–60 C.E.) and Porcius Festus (60–62 C.E.) — they keep him in custody to appease his accusers and to keep him out of trouble. Moreover, both governors find Paul’s ideas and sincerity fascinating, even if peculiar. Felix, for example, whose wife Drusilla is a Jew, often speaks with Paul about matters of faith and piety. Then, when Felix is recalled to Rome, Festus asks Paul to present his case before a special visitor who has come to pay his respects to Festus on his new governorship: Herod Agrippa II.

Herod Agrippa II is the son of Herod Agrippa I, who had killed James, the first of the twelve disciples to be martyred (Acts 12). He is also the great grandson of Herod the Great, under whose reign Jesus was born and who, according to the Gospel of Matthew, tried to kill the newborn “King of the Jews.” Despite his ancestral history of opposition to Christianity, Agrippa II is impressed by Paul’s preaching, though not enough to become an adherent. In response to Paul’s invitation to believe in Jesus, Agrippa says, “Do you think in so short a time you can convince me to become a Christian?” Paul’s retort underscores his sincerity, even in the face of a rhetorical question:

Whether in a short time or long, I pray to God that not only you but all those listening to me today would become as I — except for these chains.

—Acts 26:29

Agrippa agrees that Paul has done nothing to deserve imprisonment or death. However, in an earlier trial, Paul had appealed to Caesar, the Supreme Court of his day, and so Agrippa and Festus are obliged to send him on to Rome.

Paul’s journey to Rome (Acts 27–28)

Paul’s trip to Rome is an adventure. The large ship on which he and his companions make their journey encounters a severe storm known as the Northeaster, which pushes the ship out into the open seas. After more than two weeks of rough sailing, and with food in short supply, Paul receives a visit from an angel who tells him that all the passengers will survive and that he and his companions will make it safely to Rome. It’s a good thing Paul has this assurance, since the next day the ship wrecks and sinks, but not before everyone gets off safely.

Eventually arriving in Italy, Paul is greeted by the Christians there, who, along with the armed guard, escort him to Rome, where he is placed under house arrest. Paul remains under house arrest for at least two years, where he preaches to his fellow Jews and his Roman captors and writes letters to various churches (discussed later in this chapter). Acts ends with the following report:

For two years Paul remained in his own rented house and welcomed any who came to him. He preached about the Kingdom of God boldly and without hindrance and taught about the Lord Jesus Christ.

—Acts 28:30–31

What happened after this is not entirely clear. Some think Paul remained in Rome and was martyred under Nero’s persecution of 64 C.E. Yet, evidence from later church tradition and Paul’s own writings suggest that he was eventually released and went on a fourth missionary journey, where he ventured as far as Spain. By this account, Paul was later arrested again and beheaded around 67 CE. Whatever the exact circumstances of his death, Paul left quite a legacy.

Say It in a Letter: Paul’s Letters

Whereas Jesus’ life and teachings provide Christianity with its foundation (or “corner stone” as the New Testament puts it), Paul’s letters build the structure. His insights into human nature, faith, and the meaning of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection give Christianity some of its most important doctrines.

Paul’s letters fall into two categories:

Church epistles: Letters to communities of Christians (“churches”)

Church epistles: Letters to communities of Christians (“churches”)

Pastoral epistles: Letters addressed to individual church leaders

Pastoral epistles: Letters addressed to individual church leaders

Paul’s church epistles

Paul’s main purposes in writing his church epistles are to (1) instruct churches about the central tenets of Christianity and (2) encourage Christians to live righteously in a world that doesn’t share their values or beliefs. Here’s a brief survey of Paul’s church epistles.

Romans

Paul wrote Romans near the end of his third missionary journey (around 57 C.E.). Although he hadn’t been to Rome at the time of his writing, he was well acquainted with the church there, mentioning numerous people by name in the letter. Romans is arguably Paul’s most complex theological work and has contributed to the development of many important doctrines over the centuries, including Augustine’s notion of Original Sin (Romans 5), Martin Luther’s ideas about justification by faith alone (Romans 3–4) and John Calvin’s doctrine of predestination (Romans 9). In fact, Luther’s study of Romans, in combination with his work on Galatians (discussed later in this section), provided the theological impetus for the Reformation (16th century).

Despite its complexity, the central thesis of Romans is quite straightforward. Paul himself summarizes it near the beginning of his letter:

For I am not ashamed of the gospel for it is the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes — first to the Jews and then to the Gentiles.

—Romans 1:16

In the remainder of the letter, Paul develops this thought, explaining (1) how the gospel provides all that’s necessary for salvation, (2) why salvation can be achieved only by faith, and (3) how God’s inclusion of the Gentiles among His “chosen” fits in with His earlier choice of the Jews.

Concerning his first point, Paul argues that everyone, Jew or Gentile, “has sinned and falls short of God’s glory, and is justified freely by His grace through the redemption that comes by Christ Jesus” (Romans 3:23–24).

This leads to Paul’s second point: that everyone, Jew or Gentile, is ultimately made right (or “justified”) before God through faith in Jesus’ payment for sin “apart from works of the law” (Romans 3:28). This salvation “apart from works of the law” doesn’t mean that God has abandoned the law previously given to Moses in the Hebrew Bible. Quite the contrary, Paul argues that Jesus’ death underscores the importance of the law — whether the Mosaic Law (Jews) or the “law of conscience” (gentiles) — because violations against God’s law required that He sacrifice His own Son. Moreover, Paul reminds his readers that even Abraham, the ancestor of the Jews, was made righteous by faith (Genesis 15:6).

This leads to Paul’s final point: God’s promises to the Jews are still valid, and one day “all Israel will be saved” (Romans 11:26). Until then, God has opened the door of faith to the gentiles to allow them to be co-heirs of His promises. Given their status as God’s chosen, Christians are to live together in unity and love. In this context, Paul gives some of his most profound moral teachings — teachings that he reiterates in many of his other letters:

Love one another with a brotherly love.

Love one another with a brotherly love.

Honor others above yourself.

Honor others above yourself.

Share with those in need, even your enemy.

Share with those in need, even your enemy.

Bless those who persecute you.

Bless those who persecute you.

Live in peace with everyone.

Live in peace with everyone.

Don’t be too proud to associate with people of low social standing.

Don’t be too proud to associate with people of low social standing.

Don’t take revenge.

Don’t take revenge.

Overcome evil with good.

Overcome evil with good.

1 and 2 Corinthians

Paul wrote several letters to the church at Corinth, two of which are preserved in the New Testament. (Paul mentions a third letter in 1 Corinthians 5:9, but most scholars believe that its content is preserved in the surviving letters.) Paul wrote both 1 and 2 Corinthians during his third missionary journey, the first probably while in Ephesus (around 56 C.E.) and the second while in Macedonia (around 57 C.E.). Unlike the church at Rome, Paul had been to Corinth and was even considered the church’s founder. His personal relationship with the Corinthian church is evident throughout his letters.

Corinth was an ancient Greek city with a rich historical and cultural legacy. Part of this legacy was numerous temples to the various Greek gods, the most dominant being the temples to Apollo, the god of wisdom, and to Aphrodite, the goddess of love. These two temples seem to have captured the spirit of Corinth, because, like Apollo, the Corinthians placed a high priority on the pursuit of wisdom, and, like Aphrodite, they placed a high priority on the pursuit of “love.” In fact, Corinth had become so intimately connected with ritual prostitution that the Greek verb “to corinthianize” meant “to engage in sexual relations.” The Corinthians’ love of learning and loving helps explain Paul’s focus in his letters on what constitutes true wisdom and love.

1 Corinthians

In 1 Corinthians, Paul begins by arguing that true wisdom comes not from studying philosophy or religion but from knowing God. Moreover, true wisdom finds its ultimate expression in Jesus’ death on the cross. As a result, God’s wisdom appears foolish to those who think themselves wise (1 Corinthians 1:18–31). Paul then writes his now-famous definition of love (you’ve probably heard this passage read at a wedding — even your own!):

Love is patient, love is kind. Love is not envious, boastful, proud or rude. Love is not selfish, is not easily angered, and keeps no record of wrongs. Love does not rejoice in wrong, but rejoices in the truth. Love always protects, always believes, always hopes, always endures. Love never fails.

—1 Corinthians 13:4–8

Related to his teachings on love, Paul addresses issues such as marriage and celibacy (see the sidebar “Paul on the celibacy of the clergy”), the role of women in the church (see the sidebar “Paul on women”), and the importance and place of the “gifts of the Spirit” (see the sidebar “Paul on ‘the gifts of the Spirit’”) — themes that he expresses in several of his other letters. Paul concludes this letter by answering the Corinthians’ questions about Jesus’ resurrection, which he says was witnessed not only by the disciples but also by “more than 500 people.” To Paul, the resurrection is the central hope of Christianity:

If Christ has not been raised from the dead, then your faith is futile, and you are still in your sins . . . but Christ has indeed been raised from the dead.

—1 Corinthians 15:17, 20

2 Corinthians

Paul’s second letter to the Corinthians touches on some of the same themes as his first letter, but he finds himself needing to correct their “over-correction.” For example, in his first letter Paul admonishes the Corinthians to distance themselves from sexual immorality, including a member of their church who was sleeping with his own father’s wife. Not only did the church do what Paul had asked, but they refused to allow that man back into the Christian community even after he repented of his sin (2 Corinthians 2:5–11). Instead, Paul says, “you should forgive and comfort him so he won’t be overwhelmed with excessive sorrow” (2 Corinthians 2:7).

In the majority of the letter, however, Paul defends why he hasn’t visited the Corinthians as he said he would. Some understood this as Paul going back on his word, which undermined his authority (2 Corinthians 1:12–24). Paul tells them that his change in itinerary was for their own good, giving them a chance to clean house (2 Corinthians 2:1–4, 12:14–21). Moreover, he assures them that he’ll visit them soon to collect their promised offering for the poverty-stricken Christians in Jerusalem, as well as encourage those who have remained faithful to his message and to deal severely with those who have spread falsehoods about him in his absence.

Paul on the celibacy of the clergy

As part of Paul’s solution to the problem of sexual immorality, he recommends marriage. As he puts it, “It’s better to marry than to burn [with passion]” (1 Corinthians 7:9). For those not “burning,” Paul recommends remaining unmarried so that they can be undistracted in their service to God. Paul admits, though, that most people don’t have this “gift,” and that other apostles, such as Peter, have wives and serve God just fine. Over the next thousand years, many men and women took Paul’s advice on celibacy to heart, and celibacy gradually became the ideal for those wanting to devote themselves fully to God’s service. Then, in the 11th century C.E., what Paul put forth as a recommendation Pope Gregory VII made a requirement for all those wanting to serve as clergy in the Catholic Church. When the Protestant Reformation took place in the 16th century, the celibacy of the clergy was one of the first things to “go out the window” — literally, as Martin Luther, a (former) Catholic monk, married a (former) Catholic nun after helping her escape from her convent through a window.

Galatians

Paul probably wrote Galatians while in Ephesus during his third missionary journey (around 55 C.E.). “Galatia,” whether referring to the Roman province by that name or to the ethnic region where Celtic tribes had settled (yes, related to the ancestors of the good ol’ Irish), was located in northern Asia Minor. Whatever the exact geographical locale of these Christians, they were, according to Paul, in real spiritual peril. After Paul’s departure, certain “Judaizers” (Jewish Christians who believed that the Mosaic Law, and especially circumcision, was incumbent on all Christians) came in and started preaching a different gospel. Paul adamantly opposes this new gospel, saying that to add to what Jesus has already accomplished on the cross “is to say Christ died needlessly” (Galatians 2:21). For Paul, “a person is not justified by the works of the law but through faith in Jesus Christ” (Galatians 2:15).

Paul goes on to say that he even had to confront the apostle Peter on this matter because Peter distanced himself from gentile Christians when certain Jewish Christians were present, which implied that there was a distinction between Jewish and gentile Christians. Paul explains that in God’s eyes, “there is neither Jew nor Gentile, slave nor free, male nor female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus” (Galatians 3:28). However, he is careful to add that this newfound freedom does not mean that you can do whatever you want. As he puts it, “We were called to freedom, but do not use your freedom to indulge the flesh, but rather serve one another in love — for the entire Law is embodied in the single command: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself’” (Galatians 5:13–14). According to Paul, the ability to live the life of love comes from God’s Spirit, the fruit of which is “love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control” (Galatians 5:22–23). As Paul says, “against such things there is no law.”

Ephesians

Paul made Ephesus his “base of operations” for several years during his third missionary journey, and he is thought to have written several of his church epistles from there. Yet, when Paul writes to the church at Ephesus, he is not traveling, but rather in prison, probably in Rome (around 60 C.E.). Perhaps as a result of the time Paul spent in Ephesus, the Ephesian church doesn’t seem to have any major problems requiring Paul’s attention. This allows him to focus on the benefits of being “in Christ,” which Paul says gives them “every spiritual blessing in the heavenly realms,” including “being adopted” as God’s children, receiving “forgiveness of sins,” and having access to “all wisdom and understanding” (Ephesians 1–2).

In keeping with this positive tone, Paul tells the Ephesians not to be distraught over his imprisonment, but to use the example of his suffering to motivate themselves in their own service to God and one another (Ephesians 3). For Paul this means treating one another with gentleness and love in order to maintain unity, because Jesus destroyed “the dividing wall of hostility” that separated people of diverse backgrounds and cultures (Ephesians 4).

Part of maintaining unity requires that the Ephesians “submit to one another” (Ephesians 5:21). In this context, Paul outlines the various roles of different members of the Christian community, including husbands and wives, parents and children, and slaves and masters. Wives should submit to their husbands, while husbands should love their wives “even as Christ loved the Church and gave himself up for her” (Ephesians 5:25). That is, although Paul believes that everyone should “submit to one another,” he still maintains a distinction of roles and authority within the home (see the sidebar “Paul on women”). Paul continues by saying that children should obey their parents and slaves should obey their masters (see the sidebar “Paul on slavery”). Again, this is a two-way street, as Paul tells fathers (interestingly, not mothers) not to exasperate their children and masters not to mistreat their slaves. As Paul says, “for with God there is no favoritism” (Ephesians 6:9).

Paul concludes Ephesians by telling his readers to remain “strong in the Lord” by putting on “the full armor of God,” which he describes by equating Roman armor with a Christian’s “spiritual” armor. For example, Paul calls the scriptures a sword, and faith a shield. Apparently, Paul learned a little something about Roman armor during his imprisonment!

Philippians

Paul not only spent time in Philippi, he did time in Philippi, having been put in jail for “teaching customs unlawful for Romans” (see Acts 16). It’s ironic, then, that Paul is again in prison when writing this letter (probably in Rome around 61 C.E.). Far from being disheartened, Paul considers his imprisonment an advantage because it has resulted in the spread of the gospel “throughout the whole palace guard” (Philippians 1:13), and it has encouraged others to preach “more boldly and fearlessly” (Philippians 1:14). Also striking in this letter is Paul’s emphasis on being “joyful” or “rejoicing” — words he uses some 16 times, such as in the admonition, “Rejoice in the Lord always! Again, I say rejoice!” (Philippians 4:4).

Yet things are not all joy and rejoicing in Philippi. Whether due to their pride in being Roman citizens or in having retired military in their midst (or both), the church at Philippi was struggling to remain humble, which was causing divisions. Paul combats the Philippians’ pride by reminding them that their true citizenship is not Roman but “in heaven” (Philippians 3:20). Moreover, Paul gives them the ultimate example of humility — Jesus:

Who though existing in the form of God did not consider equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself by taking the form of a servant, and being found in the likeness of humankind and in the appearance of a man, he humbled himself by becoming obedient to death, even death on the cross.

—Philippians 2:6–8

Because a Christian’s confidence should not be in his or her accomplishments, Paul warns the Philippians about those who say circumcision is necessary for salvation. Using words that would one day adorn fences all over the world, Paul says, “Beware of the dogs!” (Philippians 3:2). Only these are not canine predators but humans “who mutilate the flesh [circumcision].” For those wanting to boast, Paul reluctantly gives his life as an example, having been raised “a Hebrew of Hebrews,” trained as “a Pharisee,” and demonstrating his zeal for God by “persecuting the church.” Paul now considers all this “loss in comparison to the surpassing value of knowing Christ Jesus my LORD” (Philippians 3:8). In fact, when describing the relative value of his former life to his life in Christ, Paul calls his former life skubalon, a Greek word meaning “dung.” Now that’s quite a contrast!

Paul on “the gifts of the Spirit”

In several of Paul’s letters, he refers to certain “gifts” that all Christians receive upon believing in Jesus and receiving the Holy Spirit. These gifts include wisdom, knowledge, faith, healing, miraculous powers, prophecy, discernment, and speaking in various languages or “tongues” (see 1 Corinthians 12). At Corinth, however, these gifts became another point of pride, with those having the more “visible” gifts (speaking in tongues, prophecy, and so on) feeling superior to those with less noticeable gifts. In response to this problem, Paul uses the analogy of the body, asking rhetorically, “If the whole body was an eye, where would the sense of hearing be? And if the whole body was an ear, where would the sense of smell be?” (1 Corinthians 12:17). For Paul, “there are many parts but one body.” In the context of Paul’s discussion of gifts, he gives his famous treatise on love (1 Corinthians 13) — because there is no greater gift one can possess or give.

Colossians

Although Paul had not been to Colosse, one of his converts, Epaphras, whom Paul met during his three-year stay at Ephesus, founded the Colossian church. Some date the letter of Colossians to Paul’s stay at Ephesus (around 55 C.E.), but he probably wrote it during his Roman imprisonment (around 60 C.E.). Paul’s letter addresses what’s been called the “Colossian Heresy,” which, as its name implies, means that we have no idea what it was. Some identify this heresy with an early form of gnosticism, a belief system that emphasized the importance of “secret knowledge” in attaining salvation. The central tenet of this secret knowledge was that all matter, including the body, is evil, and that only the spirit has any value. This belief system resulted in a diminishing of Jesus’ stature, (because Jesus “became flesh” when he came to earth) and an overemphasis on legalism (to combat the sinful desires of the flesh).

Paul deals with the diminishing of Jesus’ stature and the premise of this heresy together by describing Jesus as “the image of the invisible God” (which underscores Jesus’ divine nature), who created “all things,” both “in heaven and earth” (which affirms the basic goodness of both the spiritual and material world). Moreover, Paul says that “in Jesus all the fullness of God [exaltation of Jesus] dwells in bodily form [importance of physical matter]” (Colossians 2:9). Paul addresses the problem of legalism head on, saying, “Don’t let anyone judge you by what you eat or drink, by a religious festival, a new moon or Sabbath day. These are merely shadows of things to come, the reality, however, is in Christ” (Colossians 2:16–17). This leads Paul to his main point concerning this heresy’s pretended “knowledge”: that all true knowledge is found in Jesus. As Paul puts it:

My hope is that they are encouraged in heart and united in love, so that they may have all the riches of complete understanding, in order that they may have the knowledge of God’s mystery: namely, Christ, in whom are hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge.

—Colossians 2:2–3

1 Thessalonians

First Thessalonians is believed to be Paul’s earliest letter, and perhaps the earliest letter of those preserved in the New Testament. Usually dated to about 50 C.E., 1 Thessalonians was most likely written during Paul’s second missionary journey shortly after he preached in Thessalonica (Acts 17). According to Acts, Paul had to leave Thessalonica quickly due to opposition that arose there against his preaching. Thus one of Paul’s main concerns in this letter is to instruct and encourage the Thessalonians in their newfound faith, especially in light of the persecution they, too, were facing.

The Thessalonians seemed to be under the impression that all those who believed Paul’s message would live until Jesus returned to take them to heaven. But because some had already died (whether due to persecution or to another cause is unclear), the Thessalonians wanted to know what would happen to them. This provides Paul the opportunity to explain the doctrine popularly known as “the Second Coming of Christ.” Paul writes:

The Lord himself will come down from heaven with a loud shout, with the voice of the archangel and the trumpet call of God, and the dead in Christ will rise first. After that, we who are still alive and are left will be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air — and so we will be with the Lord forever.

—1 Thessalonians 4:16–17

The event Paul describes — where Christians both dead and alive are taken from earth into heaven, is called the Rapture by theologians. Paul is quick to point out, however, that no one really knows when this event will happen, since Jesus’ coming will be “like a thief in the night” (1 Thessalonians 5:2). Therefore, Christians should live as though Christ could come at any time.

2 Thessalonians

Paul’s reasons for writing 2 Thessalonians are similar to those prompting his first letter, namely

To encourage the Thessalonians to continue in their faith despite being persecuted

To encourage the Thessalonians to continue in their faith despite being persecuted

To admonish them to be diligent in their work, since many thought Jesus’ imminent return made working useless

To admonish them to be diligent in their work, since many thought Jesus’ imminent return made working useless

To clarify his teachings on Jesus’ return

To clarify his teachings on Jesus’ return

On the first point, Paul assures the Thessalonians that those who suffer in this world will be rewarded in God’s kingdom, and those who are persecuting them will pay for their wrongdoing (2 Thessalonians 1:8–10). Concerning the need to work diligently, Paul states plainly: “If a person does not work, he should not eat” (2 Thessalonians 3:10). Paul also warns the Thessalonians that before Jesus returns, “the man of lawlessness,” who will oppose God, will arise and even proclaim himself to be God. This lawless one will come from Satan and will be able to perform miracles and signs in order to deceive people into believing in him (2 Thessalonians 2:1–7). But Paul encourages the Thessalonians not to fear since God loves them and has chosen them. Moreover, the Lord will “overthrow [the lawless one] with the breath of his mouth and destroy him by the splendor of his coming” (2 Thessalonians 2:8). Until then, Christians are to work hard, keep the faith, and do what’s right.

Pastoral epistles

Paul’s pastoral epistles, which include 1 and 2 Timothy, Titus, and Philemon, are addressed to leaders (or “pastors”) responsible for “shepherding” the church. Timothy and Titus were Paul’s traveling companions whom he sent to churches to provide leadership and instruction in the Christian faith. Paul’s letter to Philemon is unique in that it has more to do with a personal concern between the two of them than about the administration of the church. However, the content of that letter was thought important enough to be included in the New Testament and has subsequently played an important role in debates over the Bible’s perspective on slavery.

1 and 2 Timothy

Timothy was a traveling companion of Paul, joining him on his second journey and staying with him on and off until Paul’s death. As further indication of their close relationship and work together, six of Paul’s letters (2 Corinthians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 and 2 Thessalonians, and Philemon) mention Timothy as a co-author. Moreover, Paul requested that Timothy be with him during his imprisonment in Rome near the end of his life.

1 Timothy

Although the date of Paul’s first letter to Timothy is uncertain, he most likely wrote it during his first imprisonment in Rome (around 60 to 62 C.E.) or, if he was subsequently released, during his fourth missionary journey (around 62 to 67 C.E.). After a brief reminder of why he sent Timothy to the Ephesian church, Paul recalls how God graciously saved him even though he once persecuted the church. For Paul, this proves one thing:

Christ Jesus came into the world to save sinners of whom I am the foremost. Yet this is the very reason I was shown mercy: so that in me, the worst of sinners, Christ Jesus might show his unlimited patience as an example for those who would believe on him for eternal life.

—1 Timothy 1:15–16

In other words, if God could love someone like Paul, He could love anyone.

Paul then moves on to talk about various issues relating to the administration of the church, in particular church worship and leadership. Regarding worship in the church, he writes on everything from prayer to women’s dress and behavior. Concerning prayer, he emphasizes the importance of praying for everyone, including governmental authorities, “so that we might live in peace and quiet, in all godliness and holiness” (1 Timothy 2:2). He encourages women not to be preoccupied with external beauty, such as “braided hair, gold or pearls or expensive clothes,” but to focus on the internal qualities of “faith, love and holiness” (see the sidebar “Paul on women”). Regarding church leadership, Paul describes the qualifications necessary for leaders, including being “the husband of one wife, temperate, self-controlled, respected, hospitable, able to teach, not a drunkard, not violent but gentle, not argumentative, not a lover of money” (1 Timothy 3:2–3).

In this context, we begin to see the manifestation of what you might call a primitive hierarchy in the church. Paul refers to two “offices”:

Overseers (also “elders”), which comes from the Greek word episkopos (from which we get the words bishop and Episcopal)

Overseers (also “elders”), which comes from the Greek word episkopos (from which we get the words bishop and Episcopal)

Deacons, which comes from the Greek diakonos, meaning “to serve”

Deacons, which comes from the Greek diakonos, meaning “to serve”

The primary duties of an overseer include teaching and preaching, administrating the church’s affairs, and protecting the church from error. The primary duty of a deacon, as the word suggests, is to “serve” or assist the elders in their duties, especially by freeing them up to teach and preach (see Acts 6:1–6). Paul says that those who serve the church well will be rewarded by God (1 Timothy 3:13) and should be rewarded by the church (1 Timothy 5:17). Paul then warns Timothy to beware of those who seek to lead others astray, especially those who “forbid marriage and order people to abstain from certain foods, which God has created to be received gratefully by those who believe and know the truth” (1 Timothy 4:3).

While on the subject of church administration, Paul gives advice on the various relationships within the church. For example, he says that the church must take care of widows if they have no family and are over 60 or can’t take care of themselves. Moreover, he says that slaves should show respect to their masters and, if they have a believing master, should show them no less respect simply because they are brothers (see the sidebar “Paul on slavery” later in this chapter). He concludes by warning Timothy of the snare of riches, saying that “the love of money is the root of all evil” (1 Timothy 6:10). Paul encourages those who are wealthy in this life to be “rich in good deeds, being generous and willing to share” (1 Timothy 6:18). “In this way,” he says, “they will lay up treasure for themselves [in heaven].”

2 Timothy

In 2 Timothy, you read the parting words of a man who has given his life for the gospel. Paul begins by encouraging Timothy to remain faithful to the gospel, reminding him that “God has not given us a Spirit of timidity, but of power, love and discipline” (2 Timothy 1:7). These words are particularly apropos because Paul himself sits in prison, awaiting his own imminent death under the Roman Emperor Nero (around 64 or 67 C.E.). Making matters worse, many of Paul’s closest companions have deserted him. Thus Paul turns to the subject of remaining faithful, telling Timothy that “in the last days” people’s hearts will grow increasingly cold and therefore “everyone who wants to live a godly life in Christ Jesus will be persecuted, while evil men and impostors will go from bad to worse, deceiving and being deceived” (2 Timothy 3:12–13). But because God will ultimately vindicate those who “keep the faith” and judge those who oppose it, Paul encourages Timothy to endure his present hardship and continue in his work of leading the church.

Before his closing remarks, Paul gives a moving epitaph on his life:

For I am already being poured out like a drink offering, and the time has come for my departure. I have fought the good fight. I have finished the race. I have kept the faith. Now there is stored up for me the crown of righteousness, which the Lord, the righteous judge, will award me on that day — and not only me but all those who have longed for his appearing.

—2 Timothy 4:6–8

Titus

Based on evidence within the letter of Titus, Titus was introduced to Christianity by Paul and subsequently joined Paul on his third missionary journey. Assuming that Paul was released after his so-called “first” Roman imprisonment (60–62 C.E.), this letter suggests that they joined up again, working on the island of Crete and then on the western coast of Greece.

According to 2 Timothy 4:10, Titus eventually went to Dalmatia (modern-day Yugoslavia) to preach the gospel. At the time of Paul’s writing, Titus is on the island of Crete, where Paul had left him to provide leadership to the church there. As a result, Paul writes to give Titus advice on the administration of the church as well as on how to handle false teachers. Paul’s advice on the qualifications of leaders mirrors that of 1 Timothy 3, although Paul places special emphasis on an elder’s ability to teach, probably due to the false doctrines being promoted on Crete. Paul mentions specifically what he calls the “circumcision party,” who demanded that Christians be circumcised. According to Paul, “They claim to know God, but by their actions they deny Him” (Titus 1:16). Paul quotes from a famous sixth-century B.C.E. Cretan poet, Epimenides, who said, “Cretans are always lying” (Titus 1:12) — the irony being that the speaker was a Cretan.

Paul then gives instruction to various members of the church, including the elderly, husbands and wives, and slaves and masters. He enjoins them all to

. . . live self-controlled, upright and godly lives in this present age, while we await the blessed hope of the glorious appearing of our great God and Savior, Jesus Christ, who gave himself for us to redeem us from all evil and to purify for himself a people of his very own, who are eager to do what is right.

—Titus 2:12–14

Paul on women

Few issues in New Testament studies are more controversial than Paul’s views on women. Part of the controversy stems from passages like those found in 1 Corinthians 14 and 1 Timothy 2, in which Paul says that he doesn’t allow women to speak in church. The exact intent of these passages has been the subject of considerable debate. Given Paul’s earlier acknowledgment that women prophesy in public gatherings (1 Corinthians 11:5), many scholars think that Paul’s teaching refers to disruptions by particular women during church meetings. Others suggest that Paul didn’t want to cause unnecessary offense to those accustomed to male leadership in public religious life. Still others argue that, although Paul held to the basic equality of men and women (Galatians 3:28), he believed that God ordained male leadership in the home and church. Whatever Paul’s exact intent in these particular passages, Paul elsewhere acknowledges and even praises women for their leadership in the church (see, for example, Romans 16).

Philemon

Paul likely wrote Philemon at about the same time he wrote Colossians (around 60 CE), because Philemon was a member of the Colossian church and Paul probably sent both letters at the same time. Although Paul addresses the letter to three people, it becomes clear that he’s really writing to Philemon about a personal issue: Philemon’s slave, Onesimus. For reasons that are not entirely clear, Onesimus had been with Paul for some time, during which time he had become a Christian. The traditional view that Onesimus had stolen something from Philemon and then, having regrets, asked Paul to represent him before his master is possible. A more likely scenario, however, is that Philemon sent Onesimus with a gift to Paul, and Paul asked him to stay, both out of a desire to see him become a follower of Jesus and to use his services. In this regard, Paul even makes a wordplay on the name Onesimus, which means “useful”: “Formerly he was useless to you, but now he has become useful both to you and to me” (Philemon 11).

Thus, what was probably stolen from Philemon was Onesimus’ time, and Paul was the one responsible. But Paul is careful to remind Philemon that he owes Paul much more than the wages lost by Onesimus’ absence: namely his eternal life, since Paul introduced Philemon to Christianity. Now that Onesimus is also a Christian, Paul tells Philemon to treat Onesimus “no longer as a slave, but better than a slave — as a dear brother” (Philemon 16). Paul then asks Philemon to prepare a room for him, because he expects to be released from prison soon. Finally, Paul sends greetings to Philemon from several people who are with Paul in prison, including Mark, the believed author of the Gospel of Mark, and Luke, the reputed author of the Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts. (Paul hung out in quite a literary circle.)

Paul on slavery

Paul never explicitly condemns slavery, a fact that later supporters of slavery used to defend their “right” to own slaves. Yet Paul clearly states that slavery is not God’s ideal and that it is even an appalling practice to God. For example, in 1 Timothy 1:10, Paul includes slave traders among those who are unworthy of the Kingdom of God, even calling them “godless and sinners.” Moreover, on a number of occasions Paul underscores the basic equality of humankind, saying explicitly that with God there is neither “slave nor free” (Galatians 3:28). Paul’s own attitude about slaves comes out quite clearly in his correspondence with Philemon, in which he instructs him to treat Onesimus “no longer as a slave, but . . . as a dear brother” (Philemon 16).

So why didn’t Paul explicitly condemn slavery? Some have suggested that Paul was convinced Jesus would return soon, and therefore his first priority was to see individuals believe in the gospel. For the same reason, Paul never explicitly condemned any institution, even the corrupt imperial rule of Rome that was responsible for the deaths of many Christians, including, eventually, his own. Others have argued that Paul, realizing that he had no power to abolish slavery himself, spent his time instructing Christians how to make the best of a bad situation. Still others have argued that Paul realized that real change comes from within, and that the inevitable outcome of his teaching on the basic equality of humankind — regardless of ethnicity, gender, or social standing — if embraced, would eventually transform society and topple corrupt institutions like slavery. Certainly those opposed to slavery, like the abolitionist William Wilberforce of England, found a ready defender for their cause in Paul.