Chapter 24

The Bible and the Abrahamic Faiths: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam

In This Chapter

Engendering Judaism, Christianity, and Islam with Abraham

Engendering Judaism, Christianity, and Islam with Abraham

Visiting Jerusalem, the sacred City of Peace

Visiting Jerusalem, the sacred City of Peace

T he extent to which your life impacts others cannot be entirely known. Yet, despite what you may recall from A Christmas Carol, It’s a Wonderful Life, and about every other Star Trek episode, individuals rarely alter the world’s general flow. However, once in a great while, a person comes along who actually changes the course of history. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in the story of Abraham, who laid the foundation for three distinct, though intimately related, religions: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

In this chapter, you discover the shared heritage of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam through their common bond in Abraham and Jerusalem.

Abraham: Father of Many Nations and Faiths

Abraham first appears in the Book of Genesis — a book full of beginnings, as the name implies (see Chapter 3). When we meet Abraham, however, his name is not Abraham, but Abram, meaning “exalted father.” Yet, as happens often in the Bible, God gives Abram a new name, marking a new beginning for him and those coming after him (see Chapter 5). Abraham means “father of many,” which is ironic because at the time of his name change, Abraham and his wife, Sarah, are childless. Moreover, they are 99 and 89 years old, respectively. But God has a new beginning for them, and He guarantees this with a contract, or covenant (see Chapters 2 and 4):

No longer will your name be Abram, but Abraham, for I have made you the father of many nations. I will make you very fruitful; and I will make nations from you, and kings will come from you. And I will establish My covenant between Me and you and your descendants for generations after you for an everlasting covenant: to be God to you, and to your descendants after you.

—Genesis 17:5–7

God further tells Abraham that one day his descendants will be as numerous as the sand on the seashore and the stars visible in the sky. Unfortunately, we’re too busy to count sand, but an astronomer friend of ours estimates that there are about 6,000 stars visible to the naked eye. Now that’s a lot of descendants, but not even close to the incredible impact that Abraham’s offspring will have on the world. From Abraham’s physical and spiritual children come three of the world’s major religions — Judaism, Christianity, and Islam — accounting for about half of the world’s population.

Abraham and Judaism

All Jews trace their lineage through Abraham by way of his son Isaac and grandson Jacob, who later took the name Israel. For thousands of years, Jews have looked to Abraham’s life as the source of and inspiration for their own. For example, Jews circumcise their male sons on the eighth day, a practice begun when Abraham circumcised Isaac at 8 days old in obedience to God’s command and as a sign of God’s covenant with Abraham.

Beyond being Abraham’s physical descendants, and the inheritors of God’s promises to Abraham, the Jews consider Abraham to be an example of faith. Abraham believed in God enough to leave his homeland and his extended family in Mesopotamia to go to a land he had never seen. God simply said, “Go to the land I will show you.” (Genesis 12:1) No road map, no tour book, no GPS system, just “I will show you.” Abraham also trusted God enough to give back to God that for which he had waited all his life: his son, Isaac. Just as God had initially called Abraham simply to go to a land He would show him, so God commanded Abraham to go and sacrifice Isaac “on the mountain I tell you” (Genesis 22:2). Although God would stop Abraham short, Abraham’s willingness to sacrifice what was dearest to him has served as an inspiration to many throughout the centuries.

Abraham and Christianity

Though it often comes as a surprise to people, Jesus was Jewish. Jesus, like his fellow Jews, was circumcised on the eighth day, dedicated to God on the fortieth day, made pilgrimages to Jerusalem for the major feasts, and traced his lineage back to Abraham. In fact, Abraham’s life and faith directly impact the New Testament’s presentation of Jesus’ life and ministry. Not only is Jesus presented as a fulfillment of the promises made long ago to Abraham that his descendants will be a blessing to the nations, but Jesus’ own death on the cross mirrors the near sacrifice of Isaac. For example, just as Isaac carries the wood to be used in his sacrifice, so Jesus carries the wooden beam of his own cross. Some Christians even believe that Golgotha, the place where Jesus is crucified, is the same location where Isaac is nearly killed (though many place Isaac’s near-death experience on the Temple Mount; see “Jerusalem: City of Peace — And of Conflict” later in this chapter). And although in the end Isaac isn’t sacrificed, both Genesis 22 and the crucifixion share the idea of a father sacrificing his son. Finally, Abraham is held out as a model of faith that transcends ethnic, social or gender barriers. As the apostle Paul writes:

For there is neither Jew nor Greek, slave nor free, male nor female — for you are all one in Jesus Christ. And if you are Christ’s, then you are Abraham’s children, heirs according to the covenant.

—Galatians 3:28–29

Ibrahim and Islam

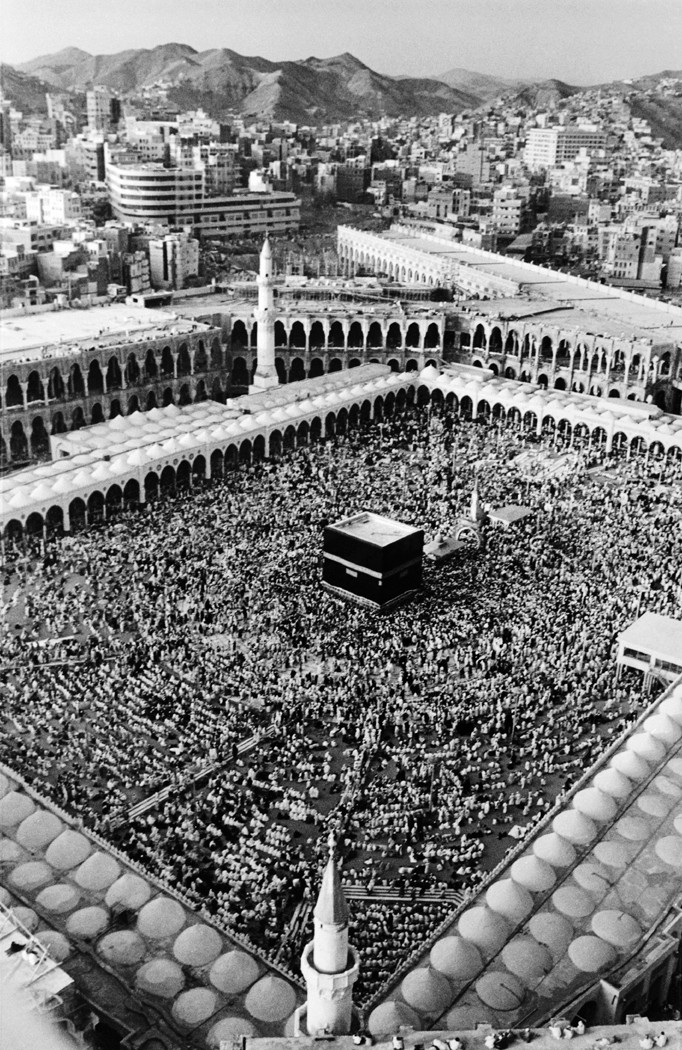

Abraham is considered by many to be the first Muslim, and for good reason: The very word Muslim means “one who submits [to God’s will].” Abraham, or Ibrahim as he is called in the Koran (Islam’s sacred text), is the model of one who submits to God, and therefore much of the Islamic religion focuses on Ibrahim. For example, one of Islam’s five daily prayers asks God to bless the prophet Ibrahim. Moreover, the direction of prayer, Mecca, is because of Ibrahim. According to the Koran, after Adam and Eve are expelled from Paradise, they build a shrine to God at Mount Arafat in Mecca. This place of worship, however, is eventually destroyed during the Flood. In its absence, religion becomes corrupted, until Ibrahim accompanies the expelled Hagar and Ibrahim’s son, Ishmael, to rebuild the shrine. This structure is what is now known as the Ka’aba (Ka’aba means “cube,” because of its shape, as shown in Figure 24-1). Today some 2 million people annually make the pilgrimage to the Ka’aba in Mecca, a practice known as the Hajj.

Islam’s founder, the prophet Muhammad, traces his descent through Ibrahim’s son Ishmael. Also, according to the Hebrew Bible, both the descendants of Isaac and Ishmael are the Chosen People, because God makes a covenant with both groups. And like Isaac, God promises that Ishmael’s offspring will become a “great nation” (Genesis 21:13, 18).

|

Figure 24-1: The Ka’aba at Mecca. |

|

©Bettmann/CORBIS

Jerusalem: City of Peace — And of Conflict

Jerusalem means “City of Peace,” but it is hard to imagine a place that has experienced more conflict over the centuries. Even today Jerusalem dominates the news more than any city in the world. Part of the reason for this is that Jerusalem lies in the middle of Israel and Palestine, a land bridge linking three continents. Thus, Jerusalem was destined to become the meeting place of different cultures. At times this cultural contact has produced violent conflict; at other times it has produced positive exchange that has greatly benefited humanity.

Jerusalem in Judaism

For Jews, Jerusalem is the most sacred city on earth, because this is where God’s home, the Temple, was located until its destruction by the Romans in 70 C.E. For many religious Jews, it is taboo to walk upon the Temple Mount until it is ritually purified. In addition, some Jews fear that by walking on the Temple Mount they may unintentionally step on the plot of ground where the Temple’s most sacred place (called the Holy of Holies) once stood. Although we can’t be certain about its exact location, many people feel that the Holy of Holies was situated under what is today the Dome of the Rock, one of Islam’s most important holy sites (see “Jerusalem in Islam” later in this chapter). Therefore, Jews today pray at the Western Wall (also known as the Wailing Wall), which is part of the foundation for the Temple built by Herod the Great (see Figure 24-2). This allows Jews to pray to God in close proximity to and facing where the Temple once stood without having to set foot on the platform.

Jerusalem in Christianity

For Christians, Jerusalem is sacred not only for its roots in the Hebrew Bible but also as the place where many events from Jesus’ life took place. Most notably, Jesus’ crucifixion, burial, and resurrection occurred in Jerusalem, which are now commemorated within the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the traditional location of these events (see Figure 24-3). Although the structure has covered over the original topography of where these events are believed to have taken place, the church’s architecture and ambience is awe-inspiring, as is the devotion of the millions of pilgrims who pass through its doors to pay homage to Christianity’s founder.

|

Figure 24-2: The Dome of the Rock and the Western Wall. |

|

|

Figure 24-3: The holiest site in Christianity, Jesus’ empty tomb is commem-orated within this stone monument located in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. |

|

Jerusalem in Islam

For Muslims, Jerusalem is known as al-Quds, Arabic for “the holy,” and is the third holiest city in Islam behind Mecca (the location of the Ka’aba) and Medina (Muhammad’s childhood home and burial site). Originally, Muhammad instructed Muslims to pray in the direction of Jerusalem, though later he changed this to Mecca. Jerusalem is important to Muslims because of its religious heritage. For example, Muslims believe that Ibrahim was ordered to sacrifice Ishmael, not Isaac. The location of this event is identified with a large stone now encased within the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. Moreover, Jerusalem is remembered as al-Aqsa, which means “the furthest place,” because here Muhammad began his night journey touring heaven. Today the al-Aqsa mosque stands on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem as a memorial to this event.