Chapter 4

The Fallout from “The Fall” (Genesis 4–11)

In This Chapter

Exploring the origins of sibling rivalry

Exploring the origins of sibling rivalry

Surviving the genealogical lists in the Bible

Surviving the genealogical lists in the Bible

Understanding why God would destroy His own creation

Understanding why God would destroy His own creation

Explaining the reasons for cultural diversity in the world

Explaining the reasons for cultural diversity in the world

T heologians have long debated the exact repercussions of Adam and Eve’s choice to eat from the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil (see Chapter 3). Did their disobedience set a bad example that the rest of humanity has followed ever since? Or did something irreparable happen to human nature that now makes us rebellious toward God (the ultimate authority figure) and alienated toward one another? Whatever the exact answer, things certainly go from bad to worse after Adam and Eve’s fateful decision.

In this chapter, we trace the effects of “The Fall” (as theologians have called it) on the generations following Adam and Eve — from the rivalry between the first two siblings to humanity’s corporate rebellion at the Tower of Babel.

The First Sibling Rivalry: Cain and Abel (Genesis 4)

Shortly after being cast out of the Garden, Adam and Eve have their first two children: Cain and Abel. Cain, the oldest, is “a tiller of the ground” (farmer) while Abel is “a keeper of flocks” (shepherd). Eventually, these two brothers bring an offering before God. For Cain, the natural choice is the produce from the ground, whereas for Abel, his offering comes from the flocks. All seems to be going fine, and then something goes terribly wrong.

Offering the first sacrifices

In a somewhat cryptic passage, the Bible says, “The LORD looked favorably upon Abel and his offering, but not on Cain and his offering” (Genesis 4:4–5). The reason for God’s preference for Abel’s offering from his flocks is unclear. Some scholars have suggested that God’s favoritism reflects a preference for a migratory pastoral lifestyle over a settled agrarian existence. And, in seeming confirmation of this interpretation, Cain, who will soon be the first murderer, will go on to build the first city (Genesis 4:17). Yet, others have suggested that this “pastoral-agricultural” reading of the Cain and Abel story is too narrow to do justice to the Bible’s universal themes of righteousness and justice. According to these interpreters, the key to understanding why Abel’s sacrifice was preferred over Cain’s is found in the language used to describe both offerings.

That Cain’s sacrifice may be a reflection of a deeper attitude problem seems confirmed by his response to the realization that God preferred Abel’s sacrifice above his: “Cain became very angry, and his countenance fell” (Genesis 4:5). God, in demonstration of His care for humankind, personally approaches Cain and gives him a warning: “If you do what is right, will you not be accepted? But if you do not do what is right, sin is crouching at your door, and its desire is for you; but you must rule over it” (Genesis 4:7). Apparently, the introduction of the knowledge of good and evil into the world has made evil a clear and present danger to humanity, as it even “crouches at your door.” Everyone is obligated, therefore, to be on guard and to struggle to overcome evil when it attacks. Cain fails in both regards.

Inviting Abel out into a field, Cain strikes his brother and kills him. Hence, the first sibling rivalry (of which there would be plenty more) ends in disaster and initiates the proceedings of the first murder trial.

Solving the first murder mystery

Shortly after Cain commits this act of murder, God shows up on the scene. Like any good detective, God begins by asking questions. And, as you may suspect, God prefers the straightforward approach: “Where is your brother Abel?” Readers of the Bible have long queried over God’s question. First of all, does God not know where Abel is? And second of all, why does God say “your brother Abel”? God merely needed to say, “Where’s your brother?” or “Where’s Abel?” or even “Where’s the other guy?”

Am I my brother’s keeper?

Cain doesn’t miss out on the gravity of God’s question, as his response reveals: “I don’t know, am I my brother’s keeper?” (Genesis 4:9). This question, intended as an escape clause, is perhaps one of the most profound teachings in the Bible. The answer is yes! We are our “brother’s keeper,” and we must do all that we can to protect and assist our fellow human beings in their journey through this life.

Demonstrating that God already knew the answer to His own question, He confronts Cain in his lie: “What have you done? Listen, your brother’s blood is crying out to me from the ground!” God gives a gripping description of murder. Although the person is gone, the effects of his death live on in this world, and, in the case of foul play, his murder cries out for justice.

Man on the run: Cain’s curse

Similar to God’s judgment on Adam and Eve, God curses Cain by telling him that he’ll be alienated from the very ground that “opened its mouth to receive your brother’s blood.” That is, the soil will no longer yield its produce to Cain because he has polluted the ground with his brother’s blood. (This pollution becomes important later; see the section, “Understanding why God would destroy His creation,” later in this chapter.) Cain’s plea is ironic: “My punishment is too great for me! Today, You have driven me away from the soil, and I will be hidden from Your face. I will be a fugitive and a wanderer on the earth, and anyone who finds me will kill me!” (Genesis 4:13–14).

Cain is concerned that he’ll be murdered. But he’s a murderer! So we may expect God to say, “Tough luck! Eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth. You killed, and so you should be killed. It’s only fair.” But, notably, God expresses mercy, even in the face of judgment: “May it not be so! Whoever kills Cain will suffer sevenfold for their deed” (Genesis 4:15). God takes the added precaution of placing a mark on Cain so that anyone seeing him will leave him alone. What this mark is remains a mystery. Some have suggested that the mark is circumcision, although how anyone would know Cain is circumcised now that humans wear clothes is an even bigger mystery. (“Whoa! Okay, okay, I won’t kill you.”)

Where did Cain get his wife?

Genesis 4:17 says that Cain “lay with his wife, and she conceived and gave birth to Enoch.” But up until this point the only people mentioned as existing are Adam, Eve, and Cain (Cain’s brother, Abel, is murdered just before this notice). So where did Cain get his wife? Although the Bible doesn’t say explicitly, Genesis 5:3–4 says that Adam and Eve had a lot of other sons and daughters. Combined with the longevity of life during this time (see “Living long in the ancient world,” later in this chapter), the earth’s population would truly “explode.” Thus, the biblical author seems to have in mind that Cain marries one of his relatives. (Incest, it seems, is not an issue at this point in the biblical text because the law forbidding incest has not yet been given.)

Tracing Your Family Tree: The First (of Many) Biblical Genealogies (Genesis 5)

Beyond their value for ancient Israel, the Bible’s genealogies sometimes convey important information about the biblical authors’ beliefs and values. For example, in Genesis 5, amidst all the “who begat whoms,” we read:

When Enoch had lived 65 years, he became the father of Methuselah. Enoch walked with God after the birth of Methuselah for 300 years, and had other sons and daughters. Thus, all the days of Enoch were 365 years. Enoch walked with God, and then he was no more, because God took him.

—Genesis 5:21–24

Most interpreters understand the notice that “Enoch walked with God” to be a euphemism for “having a close relationship with” and “obeying” God. That is, the purpose of this particular genealogical notice is to make a theological point: God rewards those who seek to know Him and do what He commands. So what is Enoch’s reward? Although some scholars have suggested that “God took him” simply means that Enoch died (hardly a reward for walking with God), most scholars agree that this phrase means that Enoch went to heaven. (In Trek-talk, God “beamed him up.”)

Living long in the ancient world

Beyond Enoch’s mysterious disappearance, the genealogies in Genesis 5 contain another peculiarity: Everyone is living sooo long. For example, look at the longevity of Enoch’s son, Methuselah who lives 969 years! That’s not bad. Methuselah is, in fact, the oldest person recorded in the Bible. Yet, this longevity may lead you to ask: “Are these human years or dog years or what?” Most likely, the biblical authors intend these years to be “normal” human years or, more precisely, lunisolar years, which are determined by counting both the sun and moon cycles. This leaves you anywhere from 5 to 11 days short for every solar year, but that’s hardly anything when talking about such large numbers (actually, it’s quite a bit when talking about such large numbers, but you know what we mean).

Now, we say that Methuselah is the oldest person in the Bible because, in ancient Mesopotamia, there existed legends of people who lived tens of thousands of years. These people, or “kings” as they’re (justifiably) called, are said to have lived before the Flood, which is precisely when the Bible also says human life expectancy was unusually high.

Deluge-ional Ideas: Noah and the Flood (Genesis 6–9)

It’s interesting that the most popular décor for a baby’s room is one of the most disturbing events recorded in the Bible: the Flood. Admittedly, pictures of colorful zoo animals filing into a boat two-by-two with a rainbow-filled background makes for cute wallpaper and bed sheets, but the biblical description of the events surrounding the Flood is anything but “cute.” For example, concerning human behavior before the Flood, the Bible says, “The wickedness of humankind was great on the earth, and every inclination of the thoughts of their hearts was on evil continually” (Genesis 6:5). That’s not cute. But it gets worse. Because of this increase in evil, God decides to completely destroy all living creatures on earth. Now, that’s really not cute. But the Flood narrative isn’t all doom and gloom.

The first “survivors”

God makes some exceptions to His plan of complete destruction. There is someone on the earth who, like Enoch before him, walked with God: Noah. Because Noah is “righteous in his generation,” God decides to spare him and his family, and, therefore, He instructs Noah to build a giant ark. Now most representations of Noah’s ark show a medium-sized boat with animals milling about on top of the deck. However, Noah doesn’t build a boat; he builds an ark, which is an antiquated English word for box or chest. And this is a good translation of the Hebrew word ‘aron because God commissions Noah to build a giant rectangular box in which to ride out the storm.

In addition, the ark has three levels, so this vessel has a lot of cubic storage space. And Noah and his family need that space because God asks them to bring “seven pairs of every kind of clean animal, and one pair of every kind of unclean animal.” (You can check out Chapter 7 for all the details about “clean” and “unclean” animals. For now, we’ll just say this isn’t a reference to their bathing habits, but rather whether they’re fit for human consumption and divine sacrifice.) The reason for needing more clean animals than unclean animals is quite simple: There’s going to be a barbeque (read: sacrifice) after the Flood, and if you have only one pair of an animal, and you kill one, then . . . you get the idea.

Soon, the ark is finished, and Noah, his three sons (Shem, Ham, and Japheth), his wife, and his sons’ wives climb aboard.

Who are the Nephilim?

According to Genesis 6, contributing to the wickedness leading up to the Flood is that “the sons of God” cohabitate with “the daughters of humans” and produce a race of “mighty heroes” called Nephilim. So who are the Nephilim? The answer to this question depends on who the “sons of God” are. Sometimes sons of God in the Bible denotes humans who have a special relationship with God. Therefore, some scholars believe the Nephilim are simply the offspring of some exceptional men, perhaps even the descendants of Seth, Adam and Eve’s son who replaces the righteous Abel. Most often, however, sons of God means angels. Therefore, many scholars believe that the Nephilim are the offspring of angelic and human cohabitation (much like the Greek Titans). Whatever the exact meaning of sons of God, the result of this union is a race of humans that, according to a later report (Numbers 13), makes grown men look like insects. Although this comparison seems a purposeful exaggeration, the Nephilim were exceptionally big, which explains their status as “mighty heroes.”

A three-hour tour . . . not!

Soon after Noah, his family, and the animals are aboard the ark, the storm begins. This rain is no spring shower, however. It’s a deluge, where God opens the “floodgates of heaven” and the “springs of the deep.” This represents an undoing of the created order God established “in the beginning” when He separated the “waters above from the waters below,” creating a space called “sky.” As evidence of the intensity of this deluge, it lasts only “forty days and forty nights,” but the water doesn’t recede to reveal dry land for over a year. During this time, we’re to imagine Noah and his family taking care of the animals (don’t worry, they packed food).

The waters subside, and the ark eventually comes to rest on Mount Ararat, which is identified today with a mountain on the border of eastern Turkey and Armenia. Having landed safely on dry ground, Noah sends out birds (first a raven, then a dove) to see if enough dry land has appeared to safely leave the ark. After a couple tries with the dove, it returns with a freshly plucked olive leaf in its beak. (The image of a dove with a leaf in its mouth has since become a universal symbol of peace.) On the third try, the dove doesn’t return. Noah now knows it is safe to leave the ark, and, at God’s command, he, his family, and the animals disembark. Noah worships God by offering a sacrifice.

Searching for Noah’s ark

Numerous expeditions have climbed Mount Ararat in search of Noah’s ark, with some people even claiming to have seen it! Yet, whether this is actually the mountain and whether the ark could have survived to the present day are questions that perhaps only Indiana Jones could answer. However, you can be certain that if someone claims to have seen the ark and then goes on to describe what sounds a lot like a boat, he or she is either lying or was hallucinating at the nearly 17,000-foot elevation.

Understanding why God would destroy His creation

Shortly after the Flood, God gives Noah some good news and some bad news. First, the good news: “I will never again curse the earth . . . nor will I destroy every living creature as I have done” (Genesis 8:21). Now the bad news: “for the inclination of the human heart is evil from its youth.” In other words, the human condition hasn’t changed as a result of the Flood. Just as every inclination of the human heart was evil before the Flood, so it is after the Flood. So if evil will still exist, why did God send the Flood?

The purpose of the Flood seems to be related to God’s “good news” item. The earth was “cursed” before the Flood. Why? Just as when Cain killed his brother Abel and the “earth received his blood,” the Bible says that after Cain’s time, “violence increased on the earth,” and, therefore, the earth took in a lot more blood. By sending the Flood, God not only judges humankind for its wrongdoings, He cleanses the soil of its pollution. In short, God is being presented as the great Cosmic Ecologist, who cleans up the earth from the damage caused by human sin. This motive for the Flood also explains the commandment, or mandate, God gives to Noah after the Flood:

Whoever sheds the blood of a human, by a human shall his blood be shed.

—Genesis 9:6

Not only does the earth have a clean start, but humans do, too, and they’re to deal more severely with murderers than God did with Cain. The ultimate reason for this commandment is tied to humankind’s being created in the divine image: “For in His own image did God make humankind.” Thus, to kill another human is to rob the world of a little bit of God’s presence.

The Noahic Covenant

God also enacts the following changes after the Flood:

First, humankind’s life expectancy will decrease until it levels off at about a maximum of 120 years. This shortening of human life is presented as an act of God’s mercy in light of humankind’s tendency toward evil. The shorter humans live, the less evil they can commit.

First, humankind’s life expectancy will decrease until it levels off at about a maximum of 120 years. This shortening of human life is presented as an act of God’s mercy in light of humankind’s tendency toward evil. The shorter humans live, the less evil they can commit.

Second, humans are now allowed to eat meat. Perhaps we’re to see in this change a certain “nutritional” purpose because the natural order and the human constitution have undergone significant changes (embodied in human’s decreasing life expectancy). Now, humans need more protein.

Second, humans are now allowed to eat meat. Perhaps we’re to see in this change a certain “nutritional” purpose because the natural order and the human constitution have undergone significant changes (embodied in human’s decreasing life expectancy). Now, humans need more protein.

Third, and corresponding to the previous change, animals are given a natural fear of humankind. Apparently, before now, animals and humans lived in relatively peaceful coexistence. Now, however, animals will have the instinct to flee the dangers of humankind (and for good reason).

Third, and corresponding to the previous change, animals are given a natural fear of humankind. Apparently, before now, animals and humans lived in relatively peaceful coexistence. Now, however, animals will have the instinct to flee the dangers of humankind (and for good reason).

Sign of things to come: Ham’s curse

That humankind really hasn’t changed after the Flood becomes evident even during Noah’s life. Noah plants a vineyard, makes wine, becomes exceedingly drunk, takes off his clothes, and passes out on his bed. One of Noah’s sons — Ham, by name — happens in upon his father and sees his father’s nakedness. However, rather than cover his father, Ham goes out and tells his brothers, Shem and Japheth, about their father’s condition. His brothers treat the situation with more delicacy by walking backward with a garment between them and covering their naked father. When Noah awakens and finds out what Ham did to him, he becomes angry and says, “Cursed be Canaan, lowest of slaves he shall be to his brothers” (Genesis 9:25).

You may ask, “Canaan? Who’s Canaan? And why is he cursed and not Ham?” Canaan is Ham’s son, and one reason Canaan is cursed and not Ham is because, in the ancient world, one’s blessedness or well-being was intimately connected to the well-being of one’s descendants. The worst possible judgment one could imagine was that your bad behavior would affect your descendants. Of course, we hardly need to be convinced that one generation’s sins affect future generations. However, the Bible gives concrete expression to this notion of “generational effects” through cursing one’s descendants.

Yet, Noah’s words also would have tremendous meaning to an ancient Israelite listening to this narrative centuries later. The Israelites lived in a land called “Canaan” — some of the inhabitants of which were their servants. As the Israelites thought themselves descendants of Shem, Noah’s curse had come to fruition in their own time. This bad outcome isn’t all because of Ham’s actions, however. According to the Bible, the Canaanites will commit many more serious crimes than Ham, and it’s for those sins that the Canaanites are ultimately judged. However, Ham gets the ball rolling.

The universality of universal flood stories

Stories of a catastrophic flood inundating the whole earth were common in the ancient world. The most notable comparison with the Bible’s account is that found in the Mesopotamian tale of Atrahasis, and retold in part in the Epic of Gilgamesh. In the account given there, the gods decide to wipe out humankind because they made too much noise, making it difficult for the gods to sleep. (If you have noisy neighbors who play their stereo until “ungodly” hours in the morning, you can appreciate the gods’ frustration.) The “Noah-figure” in these Mesopotamian accounts, whose name is given variously as Ziusudra, Atrahasis, and Utnapishtim, is warned by one of the gods of humankind’s impending doom, and tells him to build a “box” (in this account, it is truly a cube-shaped box). Other similarities include sending out birds to see if there’s dry land, landing on a mountain, and offering a sacrifice to the gods.

One difference, however, is that the Mesopotamian flood hero not only saves his family and the animals, but also some artisans and musicians, lest human culture should also perish in the flood. Another difference is that the gods, thinking they actually succeeded in killing all humankind, become frightened and angry, for now there is no one around to feed them. When they smell the flood hero’s sacrifice, the text says that, having become so famished, they swarm around the meat like flies. Whew!

Say What?! The Tower of Babel and the Birth of Nations (Genesis 10–11)

From Noah’s sons and daughters-in-law the earth is again repopulated, in fulfillment of God’s commandment to “be fruitful and multiply” (the one commandment God never rebukes humankind for not obeying). In Genesis 10, we see an account of where Noah’s sons’ descendants eventually end up:

Shem’s descendants settled mostly in the region of Mesopotamia.

Shem’s descendants settled mostly in the region of Mesopotamia.

Ham’s descendants settled largely in the areas of Canaan, Egypt, and northern Africa.

Ham’s descendants settled largely in the areas of Canaan, Egypt, and northern Africa.

Japheth’s descendants were a bit more mobile, going west into Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), Greece, and other parts of central Europe.

Japheth’s descendants were a bit more mobile, going west into Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), Greece, and other parts of central Europe.

But Shem’s, Ham’s, and Japheth’s descendants do not willingly “spread out over the face of the earth,” as God had commanded them. This forces God to shake things up a bit.

Building the Tower of Babel

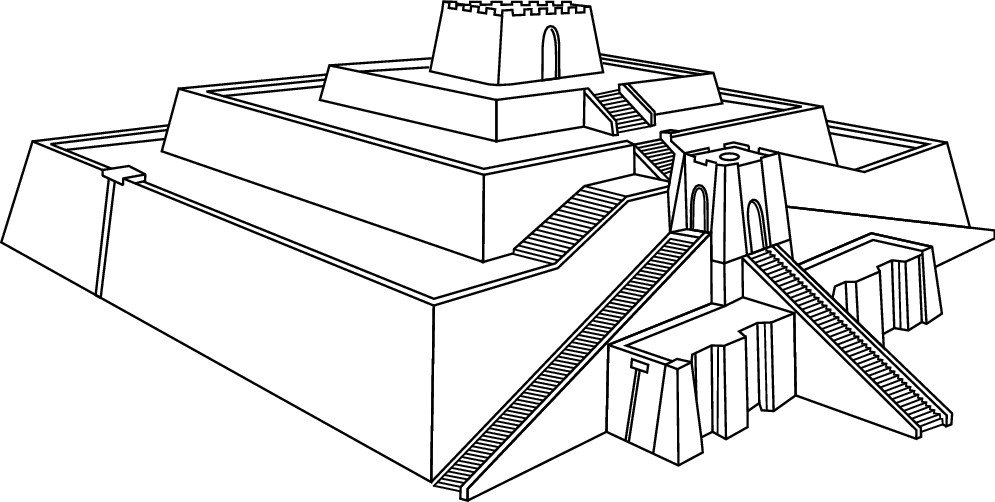

According to the Bible, Shem’s, Ham’s, and Japheth’s descendants settle together in the region of Shinar (ancient Sumer) and begin building a city (eventually called Babel) and a tower (to be named the Tower of Babel) “with its top reaching into the heavens.” Some interpreters have understood this notice to mean that the inhabitants of this city are attempting to invade heaven. This does not seem to be the case, however, because the Hebrew word for heaven (shammayim) most often means “sky.” That is, they’re just building a very high tower. The type of tower the biblical author has in mind is likely the ziggurat, which were widespread throughout Mesopotamia. At the top of these stepped towers was a palace or temple to a god (see Figure 4-1). Therefore, the inhabitants of this city seem to compound their disobedience of not spreading out by building a temple to another god.

|

Figure 4-1: The Tower of Babel described by the Bible probably looked something like this ziggurat. |

|

I’m so confused! Babbling in Babylon

What isn’t obvious in most translations of the Bible is that the word for Babel in the tower story is the same word that is translated later in the Bible as Babylonia. That is, an Israelite hearing the story of the Tower of Babel (Babylonia) would not miss its significance. This event took place in the same region where Babylon (a country that eventually would be a major political player during Israel’s later history) would arise. Moreover, this would also be the place from which the founder of the Israelite people would come; namely, Abraham. Yet, as you may imagine, the Babylonians didn’t understand their name to mean “confusion.” In fact, in Akkadian, the language of Babylonia, it didn’t. Babylon or Babel means “gateway of god.” So, to the Babylonians, their name meant something far nobler. However, to the monotheistic authors of the Bible, Babylonia, and all that it represented, was a source of confusion.

Making a name for yourself

Immediately after the Tower of Babel incident, the narrative shifts to one of those dangerous “who begat whom lists,” taking us from Shem, Noah’s eldest son, to one of the most important figures in the Bible: Abraham. You can read all about Abraham in Chapter 5, but for now, you don’t want to miss this genealogy (really, this isn’t just a couple of demented biblical scholars trying to draw you into our obsession). With this genealogy, the author makes an important theological point by way of word play. The Hebrew word for “name” is shem. So, by placing the lineage of Shem, which will culminate in Abraham, immediately after the inhabitants of Babel’s failed attempt at making a shem (name) for themselves, the biblical author is arguing that a really great name comes at God’s initiative and from doing what He commands. Confirming that the author is making this point is that he follows Shem’s lineage with God’s call to Abraham, which reads:

Go from your country . . . and I will make your name (shem) great!

—Genesis 12:1–2

And that is precisely what God does. But for that part of the adventure, you have to read Chapter 5 of this book.