Chapter 8

An Experiment in Theocracy: Joshua, Judges, and Ruth

In This Chapter

Entering the Promised Land with the Israelites

Entering the Promised Land with the Israelites

Witnessing the walls of Jericho come tumblin’ down with Joshua

Witnessing the walls of Jericho come tumblin’ down with Joshua

Overcoming oppressors with Deborah, Samson, and the other judges

Overcoming oppressors with Deborah, Samson, and the other judges

Gleaning a husband with Ruth

Gleaning a husband with Ruth

T he biblical books of Joshua, Judges, and Ruth chronicle Israel’s history from Moses’ death to the onset of the monarchy. Under the leadership of Joshua the Israelites successfully enter and conquer their Promised Land (ancient Canaan). After Joshua, Israel is ruled by judges, not in the modern sense of stoic figures in black robes, but in the ancient sense of charismatic figures who, though perhaps hearing a case or two, would lead the Israelites in battles against their enemies. The Book of Ruth focuses on the life experiences of one family during the period of the judges, who overcomes extreme hardship to become an influential member of ancient Israelite society.

During this period, Israel is loosely organized in a tribal theocracy, where God is viewed as the ultimate ruler of the confederacy. These are wild times for Israel, because it lacks a central governing authority to punish crimes and maintain order. However, wild times mean colorful characters and stories, and Joshua, Judges, and Ruth certainly do not disappoint.

Exploring the Book of Joshua

The Book of Joshua acquires its name from its main character. Joshua was Moses’ right-hand man, accompanying him on Mount Sinai as he received the Law from God, and assisting him in battle against Israel’s enemies. Joshua had also been one of two spies (Caleb was the other) who believed that God would deliver the Promised Land to Israel, despite the size of the foe. This courage, spirituality, and military prowess come in handy as Joshua leads the next generation of Israelites into their Promised Land.

Preparing to enter the land (Joshua 1)

When we pick up the action of Joshua, the Israelites are encamped on the border of the Promised Land, just east of the Jordan River. Joshua tells them to get ready, because in three days they will cross the Jordan, and when they do, there’s no turning back. The people reply:

All that you have commanded we will do, and wherever you send us we will go. Just as we obeyed Moses in all things, so we will obey you.

—Joshua 1:16–17

Although these words may seem a small consolation in light of just how infrequently the people really listened to Moses, this is a new generation, and they actually will end up obeying (most of) what Joshua commands.

Two spies and a prostitute (Joshua 2)

Prior to entering the Promised Land, Joshua sends two spies ahead to Jericho to gather strategic information. Upon entering the city, and in true James Bond fashion, the two spies go to the house of a prostitute named Rahab. (After all, if you want insider information, what better place to go than the local brothel?)

When the king of Jericho receives news of the Israelite infiltrators, he sends his soldiers to Rahab’s house. Rahab lies to the soldiers, however, saying the two spies already left the city, all the while hiding them on her roof. The reason for Rahab’s traitorous actions is that she has heard about God delivering the Israelites from their Egyptian bondage and from their enemies during their wilderness wanderings. For Rahab, the conclusion is obvious:

For the LORD your God is God in heaven above and on earth below.

—Joshua 2:11

Rahab is now a believer in this God, which was one of the desired outcomes expressed by God when He delivered Israel from its Egyptian slavery — non-Israelites would also believe in Him. Therefore, Rahab asks the spies to return her favor of lying on their behalf by sparing her and her family when (not if) they conquer the city. The spies agree and, that night, Rahab lowers them from the city wall, and they eventually make it back to the Israelite camp. In the New Testament, Rahab’s heroism is held out as an example of faith for others to emulate (Hebrews 11:31 and James 2:25).

Crossing o’er Jordan and preparing for battle (Joshua 3–5)

After the spies return, the Israelites prepare to enter the Promised Land. The final barrier to their entry, the Jordan River, actually proves insignificant because its waters miraculously roll back when the priests carrying the Ark of the Covenant (see Chapter 7) enter the river.

So that future generations would remember God’s miraculous acts on behalf of Israel, God commands that a representative from each tribe collect a stone from the dried riverbed to be made into a memorial. As Joshua says,

For your children will ask in time to come, “What do these stones mean to you?” And you will say to them that the waters of the Jordan were cut off in front of the Ark of the Covenant of the LORD. When it crossed over the Jordan, the waters of the Jordan were cut off. And these stones will be a memorial to the children of Israel forever.

—Joshua 4:6–7

Making up for past sins

When the Israelites enter their Promised Land, the manna (or divinely provided bread; see Chapter 7) that has fed them for 40 years ceases, because now they will eat the produce of this land “flowing with milk and honey.” Also making this a momentous occasion, and as further preparation for battle, Joshua has all the Israelite males circumcised. Apparently adding to the sins of the former generation, they neglected to circumcise their sons. This new generation’s obedience in this regard symbolizes their renewal of their covenant with God. In recognition of this renewal, the place of their circumcision is named Gilgal, from a Hebrew word meaning “to roll,” because “God rolled back the reproach of Israel.”

Meeting the commander-in-chief of God’s army

As Joshua is looking over Jericho in preparation for the impending battle, he is startled by a man standing in front of him with a drawn sword. Already outmaneuvered, Joshua realizes diplomacy is his best option: “Are you for us or for our enemies?” The man’s answer is perhaps more startling than his sudden appearance: “Neither. Rather I have come as the commander of the LORD’s army.” Realizing this is a divine visitor, Joshua falls on his face and asks what God would have him do. Rather than give Joshua a battle strategy, the divine visitor responds: “Take off your sandals, for the place where you are standing is holy ground” (Joshua 5:15). That’s it. No discussion, no insider scoop, just take off your sandals. So what’s going on here?

Concerning the Israelites, God is fulfilling a promise made long ago to Abraham — that his descendants would one day live in the Promised Land.

Concerning the Israelites, God is fulfilling a promise made long ago to Abraham — that his descendants would one day live in the Promised Land.

Concerning the inhabitants of Canaan, God is fulfilling another promise He made to Abraham — that He would one day judge the Canaanites for their many sins.

Concerning the inhabitants of Canaan, God is fulfilling another promise He made to Abraham — that He would one day judge the Canaanites for their many sins.

And the walls came a tumblin’ down: The defeat of Jericho (Joshua 6)

The Israelites are now ready to take Jericho, and get the conquest underway, but there is a major problem: The heavily fortified walls of Jericho separate the Israelite army from their first victory.

The walls of Jericho were renowned in the ancient world. Apparently, as one of the oldest cities of human civilization, Jericho had learned over the millennia that nothing speaks “keep out” like tall walls. The irony is that as Joshua looks at the tightly shut walls of Jericho, God says, “See, I’ve delivered Jericho into your hands” (Joshua 6:1–2).

In keeping with this “achieve the impossible” optimism, God gives Joshua very unorthodox battle plans: Have the soldiers and seven priests with trumpets parade with the Ark of the Covenant once around the city every day for six days. Then, on the seventh day, the group should march around the city seven times, and then sound all the trumpets and everyone should shout at the top of their lungs. Yeah, that makes sense. And the inhabitants of Jericho will laugh so hard they’ll fall off the wall, right? Thankfully, Joshua knew that God knew what He was doing and didn’t ask questions. And sure enough, after the seven-day ritual and primal scream, the walls collapse and the Israelites take Jericho.

A temporary setback: Stealing from God (Joshua 7–8)

Things are going great for Israel in the war department. After the miraculous defeat of the Canaanites at Jericho, Israelite spies are sent northwest to reconnoiter the city of Ai. Due to Ai’s diminutive forces, Joshua decides that only a limited army is needed to conquer. Nevertheless, they suffer an unexpected and terrible defeat.

Joshua is distressed when the bad news reaches him, and he asks God how this could have happened. God tells Joshua the defeat came because of a serious covenant violation — one of the Israelite soldiers took some of the war spoils at Jericho that belonged to God. Joshua summons the people and, using lots (biblical dice), discovers that a man named Achan stole some gold, some silver, and a beautiful robe from Jericho, and then buried the treasures inside his tent. For this sort of violation, in which religious laws of war are breached, the punishment is severe. Achan is “cut off” (Hebrew keret), meaning that he, along with his family and livestock, are stoned to death and buried along with his possessions (including the stolen items).

This religious purge does the trick, and the Israelites are successful in defeating Ai on their second try.

The Gibeonites’ trick and the total conquest (Joshua 9–12)

With Israel back on track after the setback at Ai, Israel’s conquest is rapid, using a divide-and-conquer strategy by attacking Canaan’s midsection, and then campaigning south and north. Yet, when the residents of Gibeon, a city near Jerusalem, hear of Israel’s victories, they understandably fear for their lives and come up with a tricky strategy of their own. The Gibeonites dress up like poor travelers and approach Joshua at Gilgal. They pretend to have traveled a great distance, so as to make Joshua think they are not inhabitants of the Promised Land. Without consulting God, Joshua and the Israelites make a treaty with the Gibeonites, promising never to destroy them. After three days, however, the Israelites discover their ruse, but they are unable to harm the Gibeonites due to their oath. So Joshua decrees that, from then on, the Gibeonites would become Israel’s servants.

After the episode with the Gibeonites, Joshua performs one miracle so amazing that the Bible mentions “There has been no day like it before or after, when the LORD listened to the voice of a man” (Joshua 10:14). That miracle occurs when Joshua orders the sun to stand still to give the Israelites more time to finish a battle against a coalition of Canaanite kings. Because Joshua’s order occurs some 3,000 years before Copernicus, the biblical author describes this miracle by saying “the sun stood still and the moon stopped” (Joshua 10:13), showing that truly nothing is impossible for God. With this extended time, the Israelites are able to defeat the coalition.

After this miraculous victory, the Israelites, in short order, defeat the king- doms of southern and northern Canaan. Joshua 11 ends with the report:

Thus, Joshua possessed the entire land as the LORD had said to Moses, and he gave it as an inheritance to Israel according to their tribal allotments. Then the land had rest from war.

—Joshua 11:23

Biblical war rules

Conquering Jericho and other Canaanite cities are not ordinary battles where, if successful, the soldiers divide the war spoils, including taking any desirable women or children for slaves. Instead, these are wars of “destruction” (from the Hebrew word herem, often mistranslated as “holy war”), which have their own special laws as recorded in Deuteronomy 20. During these wars of destruction, God Himself partakes in the fighting. Because God is fighting, soldiers must be both morally and ritually pure. In addition, soldiers who are fearful (or lack faith) are not allowed to fight. Moreover, if the war is fought against a city within the borders of the Promised Land, then to erase the influence of foreign religion, the destruction must be total. Men, women, children, and even livestock are to be destroyed. This divinely sanctioned genocide is disturbing, but the Bible presents this as a unique period in ancient Israel’s history. What’s more, this war is not about personal enrichment, nor is it about one side being more righteous than the other, but it is about God judging the Canaanites for their many sins and keeping His promises to Israel’s ancestors. As Moses reminds the Israelites while they are still wandering in the wilderness:

When the LORD your God drives out your enemy before you, do not say to yourself, “The LORD has given me this inheritance because of my righteousness.” It is rather on account of the wickedness of these nations . . . and to fulfill the promise He made to your ancestors Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. It is not because of your righteousness . . . for you are a stiff-necked people.

—Deuteronomy 9:4–6

New homes and renewed covenants (Joshua 13–22)

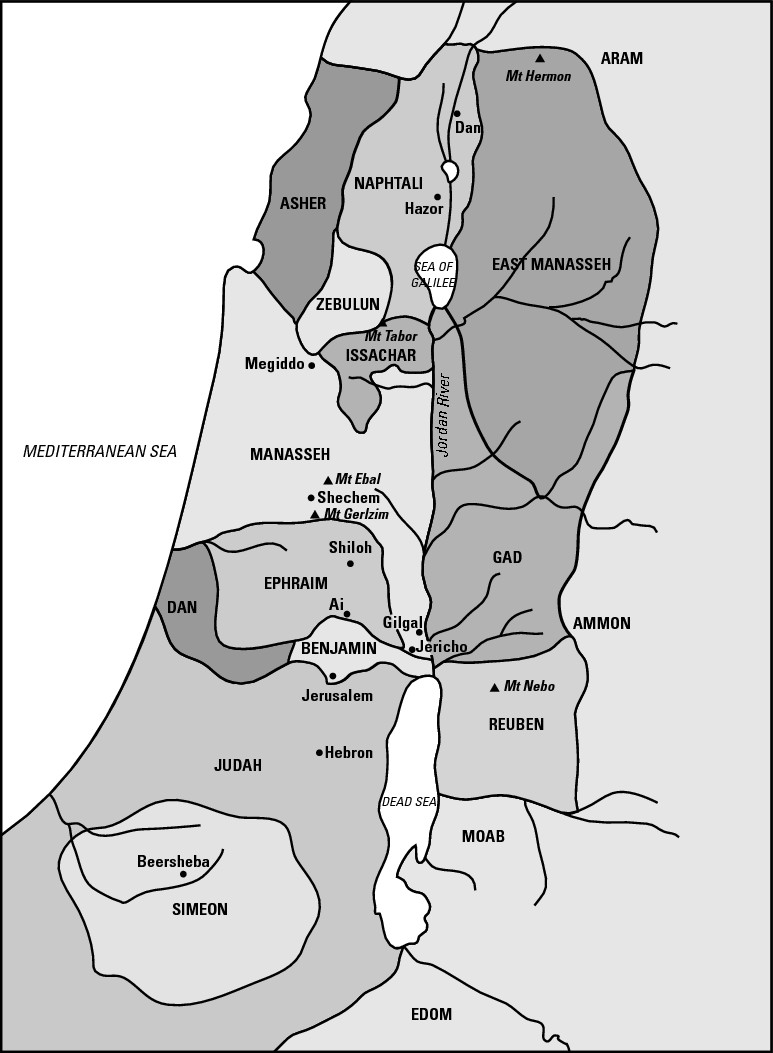

The distribution of the land of Canaan among the twelve tribes of Israel is carried out by Joshua and the priest Eleazar (Aaron’s son) by using sacred dice called Urim and Thummim. The locations of the tribal territories are depicted in Figure 8-1.

|

Figure 8-1: The territories of the twelve tribes of Israel. |

|

Although Israel is traditionally reckoned as 12 tribes, in truth, there are 13. This is because the inheritance of Joseph, one of the 12 sons of Jacob, actually is divided amongst his two sons: Manasseh and Ephraim.

So then, who gets left out when the land is divided into 12 tribal allotments? Levi. Only, they aren’t really left out. The Levites serve as priests for the tribes so they are given a total of 48 cities among the 12 tribal allotments. This ensures that there is a “priestly presence” in each tribe. Moreover, 6 of these 48 cities serve as “cities of refuge,” where someone can go for protection and justice, particularly in cases where someone unintentionally kills another (see Joshua 20-21).

Joshua’s covenant renewal and farewell (Joshua 23–24)

Near the close of Joshua, the Israelites gather one last time to renew their covenant with God. Moreover, Joshua delivers his farewell speech, admonishing the people to remain loyal to God:

And now then, fear the LORD, and serve Him in sincerity and in truth; and turn away from the gods which your ancestors served beyond the River, and in Egypt, and serve the LORD. And if it is evil in your eyes to serve the LORD, choose this day whom you will serve, whether the gods your fathers served in the region beyond the River or the gods of the Amorites in whose land you dwell; but as for me and my house, we will serve the LORD.

—Joshua 24:14–15

Joshua ends with three funerals (but no wedding). Joseph’s mummy, which the Israelites carried up from Egypt, is finally buried as he had asked the Israelites to do hundreds of years before (Genesis 50:25). Then, Joshua and the priest Eleazar die, both being buried in Ephraim.

As for the survivors, they initially follow Joshua’s instructions by obeying God, as does the next generation, but this obedience doesn’t last too long, as the Book of Judges makes plain.

Understanding the Book of Judges

Some of the all-time greatest TV shows resemble Judges, because every episode follows the same plot structure. Take, for example, the cartoon Scooby Doo. In each episode a villain tries to fool others by posing as a paranormal phenomenon, which would have worked if it hadn’t been for those meddling kids and their dog. In the same way, the cycle of Judges is quite apparent:

1. A new generation of Israelites neglects God and worships other deities.

2. God punishes them through foreign oppression.

3. The people repent and beg God to save them.

4. God delivers the people militarily through a judge.

5. The villain is then unmasked, and snarls in Hebrew: “I would have gotten away with it if it hadn’t been for those meddling kids and their dog.”

Actually we made up that last part — there are no masks in Judges, but there are plenty of villains, hijinks, and even some paranormal phenomena.

Judge not, lest you be judged: Being a judge in the ancient world

The Judges hall-of-fame (Judges 1–16)

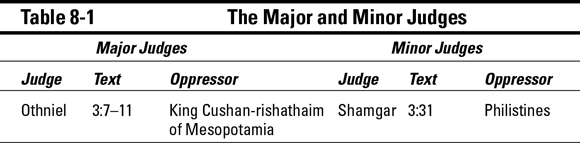

Traditionally the 12 individuals in the Bible known as judges are divided into two categories: major and minor. The major judges are so-called because they have quite a bit written about them. By comparison, the minor judges have very little recorded about them, at most three verses. For ease of reference, Table 8-1 lists the major and minor judges, where in the Book of Judges they appear, and the nation or king that is oppressing Israel when God calls a particular judge into action.

Othniel: The first judge

A couple of generations after Joshua, the Israelites begin worshiping other gods. As judgment, God allows a Mesopotamian king named Cushan-rishathaim to enslave the Israelites for eight years. The people cry out, and God selects as the Israelites’ first judge a man named Othniel, who is the younger brother and son-in-law of Caleb (Caleb and Joshua are the spies during the wilderness wanderings who had faith that God would give Israel the Promised Land; see Chapter 7). Othniel defeats Israel’s enemy in battle, bringing peace to Israel for a generation.

Ehud: Dirty jobs require getting dirty

Israel once again forsakes God, who in response sends Eglon, a Moabite king, to conquer and oppress it. Eighteen years later, Israel cries out to God in repentance, and He appoints a man named Ehud to deliver it. As Ehud is employed as a guard to oversee the safe delivery of the Israelite tribute to Moab, he is granted a private audience with the king to deliver a secret message. The guards, doing their duty, check to make sure Ehud has no weapons, and then let him in the king’s private chambers. However, what the guards fail to realize is that, being left-handed, Ehud carries his weapon, which in this case is an 18-inch dagger, on the opposite side of most fighters, allowing him to enter the king’s presence secretly armed.

During their meeting, the king sits down in what most translations say is “the upper room of his summer palace,” but which most scholars believe actually refers to his private bathroom. While the king is getting up from his “throne,” Ehud enters the bathroom, locks the door behind him, and gives the king his “message.” The stab wound results in the king losing control of his bowels, which are emptied on the floor (note the King James translation: “and the dirt came out”).

The king’s servants soon arrive and, after opening the door, find their liege dead on the floor and Ehud gone. The Moabite army pursues Ehud, but the Israelite forces under his command defeat them.

Deborah: Judge, prophetess, warrior

Deborah is one of the most remarkable people in the Bible. She is described as a prophetess, a judge who decides legal cases, and a military leader. As evidence of her influence, when she tells Barak, the Israelite military general, that God wants him to go to war against Jabin, the Canaanite king of Hazor and their oppressor of 20 years, Barak responds, “I won’t go unless you go with me.” Deborah’s response is evidence of her prophetic abilities and the Bible’s open discussion of established gender roles, “I’ll go, but know that the glory for delivering Israel will go to a woman.” Surprisingly, the woman Deborah refers to is not herself, but an unlikely heroine, whose actions are praised and used to mock the exploitation of women in the ancient world.

Deborah and Barak meet the enemy, and despite the fact that the Canaanite king had the benefit of 900 iron chariots and a skilled general named Sisera, his troops are routed. In order to allude capture, Sisera runs into the tent of a woman named Jael, who belongs to a neutral tribe in the Canaanite-Israelite wars. Jael invites Sisera to have a drink of milk and then tells him to rest. When Sisera is asleep, Jael takes a tent peg and drives it into his skull.

The prose narrative of this victory is followed by a poetic description known as the Song of Deborah. In it, Jael’s actions are praised, even contrasting her active role in helping to win the battle with the passive role of the Canaanite women, who look out their windows for the returning armies carrying their spoils, including “a girl or two for every man” (Judges 5:30). Ironically, Sisera is not bringing subjugated women home, but rather is lying dead at the feet of a woman who subjugated him in her home.

Gideon: A wimp turned warrior

The Israelites turn again to other gods, and this time a people known as the Midianites devastate them through raiding parties. The Israelites call out to God in repentance, and again God sends a deliverer. Only this is not your average hero. When we meet Gideon, he’s threshing wheat, not on a hilltop, where the wind could carry the chaff away, but in a winepress, for fear he would be spotted by the enemy.

Ironically, the angel whom God sends to commission Gideon says: “Hail, mighty warrior! The LORD is with you!” (Judges 6:12). God obviously sees something in Gideon we don’t. Gideon, in keeping with his timid character, offers several excuses to get out of being a judge, but eventually he’s convinced that he’s the right one for the job.

Gideon’s first task is to destroy his hometown’s altar to Baal, the Canaanite storm god, which just happens to be on his father’s property! After Gideon does it, the residents call for his death. However, Gideon’s father calms the crowd and says that if Baal is a real god, then he can contend for himself. This explains why Gideon’s other name is Jerubbaal, which means “let Baal contend.”

As further evidence of Gideon’s uncertainty in his new job as “mighty warrior,” God commands him to go to battle against the Midianites. Gideon, however, is unwilling unless he can be sure God is with him. As a test, Gideon sets a fleece on the threshing floor, saying that if in the morning the fleece is wet and the ground is dry, he’ll be successful in battle. The next morning it is exactly as he said. But you can never be too sure about these things, so he asks for the reverse sign the next morning — dry fleece, wet ground — and it happens. With no more excuses, Gideon goes to battle.

After Gideon gathers an army of 32,000 men, God informs him that the troops are too numerous. God wants the upcoming victory to be credited to divine power rather than human force. Eventually God whittles the number down to 300. In the end, the 300 don’t even have to raise a sword — God instructs them to surround the enemy camp at night and, at Gideon’s signal, expose lighted torches by breaking ceramic jars, yelling, and blowing trumpets. It works, and the Israelites have a resounding victory.

I will not rule over you, nor will my son rule over you. The LORD will rule over you.

—Judges 8:23

Jephthah: The consequence of a hasty vow

The next to subjugate the Israelites are the Ammonites, their neighbors to the east (see Figure 8-1). In response to Israel’s repentance and cries for deliverance, God appoints a skilled warrior named Jephthah to deliver them.

Before the conflict, Jephthah makes a vow in God’s name: “If You will give the Ammonites into my hand, then whatever comes out of the door of my house to meet me . . . I will offer as a burnt offering” (Judges 11:30–31). To an ancient Israelite audience, this would seem like a reasonable vow, because animals often lived in pens on the ground floor of homes. Thus, whatever animal happened to mosey out the door upon Jephthah’s return would be the one he’d sacrifice. Jephthah is, in fact, successful, and he goes home to fulfill his vow. However, to his horror, the first “creature” to come out the door is his only child — a daughter, who rushes out to congratulate him.

Jephthah is despondent, but his daughter insists that he keep his vow to the LORD. Her only request is that she be allowed to spend two months with her friends mourning her childlessness in the hill country. The text reports that from this event comes a custom where each year the young maidens of Israel roam about for four days in her memory.

Did I say something wrong? Minding your shibboleths

Although today the word shibboleth refers to a password or a regional dialect, it is actually a Hebrew word meaning “ear of wheat” that comes from Judges 12. Jephthah and the people of Gilead, after receiving death threats, go to war against the Israelite tribe of Ephraim. Gilead wins the battle and secures the fords of the Jordan River, controlling the only road for the scattered Ephraimite soldiers to return to their homes. Whenever a soldier appears, Jephthah’s men question if he is from Ephraim. Of course, the soldier always says no, but the Gileadites test him by making him say shibboleth. If the soldier pronounces the word sibboleth, apparently the regional dialect of Ephraim, then he is immediately killed.

Samson: A buffed Nazirite duff

The lead role in Samson and Delilah (1949) is brilliantly played by the larger-than-life Victor Mature. He could lift heavy objects, and when it came to acting like he couldn’t pronounce words exceeding three syllables, well, let’s just say that he had us all fooled. And this is exactly how the Bible portrays Samson: stronger than an ox, but not the sharpest tool in the Israelite shed.

The story of Samson begins when Samson’s mother is visited by an angel who informs her that, though barren, she will have a son. Only there’s a catch: He is to be “a Nazirite from the womb.”

Because Samson is to be a Nazirite from the womb, his mother must also abstain from these things. Yet, after Samson is out of the womb, he does nothing but break these vows. For example, on one occasion, Samson kills a lion with his bare hands, and then on a return trip to the scene of the crime he takes honey from a hive that bees made in the lion’s carcass. Now that’s at least two Nazirite strikes, because he touches a dead animal and eats a fermented substance.

When Samson isn’t eating sticky stuff from dead animals, he’s roaming the countryside sleeping with prostitutes and getting in fights. For instance, Samson kills 1,000 men with a donkey jawbone (it’s worth watching Samson and Delilah for this scene alone!) and carries a city gate 40 miles when escaping from the Philistines.

The only vow Samson does keep is not cutting his hair, which is the source of his strength. But even this vow eventually goes out the window when Delilah, the original femme fatale, convinces Samson to reveal the secret of his strength. When he finally does, she informs the Philistines, who are paying her a handsome price for this secret. While Samson is asleep on Delilah’s lap, the Philistines enter the room, cut his hair, and tie him up. Once Samson is captured, the Philistines poke out his eyes (a common procedure to prevent prisoners from rebelling), and tie him to a grinding mill that he pushes in circles to make flour. Thus, the man who roamed the countryside freely, following the desires of his eyes, now has no eyes and is forced to walk in circles. But he’s not finished yet.

As the text informs us, “his hair began to grow.” Soon Samson has a full head of hair, and his unsuspecting captors parade him in front of the Philistines during a festival at the temple of their god Dagon (the god of grain). The Philistines marvel at Samson’s size and gloat over his demise. Then, to thank their god for this victory, they enter Dagon’s temple to party. Meanwhile, Samson, who is standing between the two pillars supporting the roof, prays to God for one last moment of glory. In answer to his prayer, Samson’s strength returns, and he collapses the building, killing himself and all the Philistines inside.

In the end, everyone is dead.

Where’s the exit? The downward spiral of a nation (Judges 17–21)

The last chapters of Judges record some of Israel’s darkest days as a nation without a stable government. One episode in particular illustrates the debauchery and lawlessness of the last days of the judges.

A Levite and a concubine (sort of like a wife, only a concubine has less status and fewer rights) decide to spend the night in a town called Gibeah in the tribal territory of Benjamin. An elderly man invites them to stay at his house, but that night the people of the city surround the house and demand that the elderly man produce the stranger so that they may have sex with him (much like the sin of Sodom in Genesis 19 — see Chapter 5 in this book for more discussion on Sodom). To placate the crowd, the old man, like Lot in the Sodom story, offers his daughter, but the crowd demands the male stranger.

Seeing no other way out of this predicament, the Levite grabs his concubine and sends her out of the house. She is raped all night, and in the morning she collapses dead at the doorstep. The Levite takes her corpse home, where he cuts her into 12 pieces and sends one piece to each of the tribes of Israel. This unusual mail delivery causes a stir throughout Israel, and the people demand that the guilty people in Benjamin be brought to justice. However, the Benjaminites refuse to extradite the men, and a civil war ensues. Although initially successful, the tribe of Benjamin is almost killed into extinction by the other 11 tribes. Once the war is over, and in order to ensure the tribe’s survival, the Benjaminites are given permission by the other tribes to steal wives from a neighboring non-Israelite town.

Gleaning Wisdom from the Book of Ruth

Ruth is one of the great heroines of the Bible, and her character reminds you that not everyone during the period of the judges was morally challenged.

Ruth is a tale of heartbreak, loyalty, and love, and it offers a glimpse into the extreme hardships of poverty in the biblical world. Moreover, it seeks to present an alternative view to the harsh ethnic and cultural exclusivity common in the ancient (and modern) world.

How sweet it was to be loved by you (Ruth 1)

The opening lines of Ruth reveal the tragedies and hardships inseparable from biblical life for the poor. During a famine in Israel, Elimelech and his wife, Naomi, leave their home of Bethlehem and travel east to Moab in search of food. Their two sons, Mahlon and Chilion, accompany them. In time, Elimelech acquires a small piece of property, but soon thereafter he dies. Meanwhile, the two sons take Moabite wives: Mahlon marries a woman named Ruth, and Chilion weds a woman named Orpah. This arrangement lasts about ten years, until both of the husbands die.

Naomi, now widowed and childless, decides to return to Bethlehem, hearing that her former home now has food. Though saddened by the thought of departure, Naomi tells her daughters-in-law to return to their mothers’ houses. Initially, both girls want to travel west with Naomi, but after much coaxing, Orpah returns home. Ruth, however, grabs her mother-in-law and says:

Do not beg me to leave you, to return from after you. For where you go, I will go, and where you stay, I will stay. Your people are my people, and your God is my God. Where you die, I will die and there I will be buried. Thus may the LORD do to me and more so if even death parts me from you.

—Ruth 1:16–17

In the end, Naomi succumbs, and the two march off to Bethlehem and arrive at the onset of the barley harvest (March/April). Naomi, whose name means pleasant or sweet, asks the townspeople to call her Mara, meaning bitter, “because the Almighty has dealt very bitterly with me” (Ruth 1:20).

Picking up the pieces and choosing the right stock (Ruth 2–3)

Thankfully, Naomi has a land-owning relative named Boaz, which means that with permission they will be able to come into the field after the harvesters and glean, or pick up, any barley kernels left behind. Off of these gleanings they will live for the next year. Boaz grants Naomi permission, and Ruth makes the most of the opportunity. She hopes that while gleaning, Boaz will see her and fall in love. Boaz takes the bait, and asks Ruth not to glean from any other field except his (ancient pickup lines still had a way to go).

Ruth is treated well by Boaz, and Naomi grows excited at the possibilities. However, when the wheat harvest (April/May) arrives Naomi grows impatient at the slow growth of this budding love affair and concocts a plan to get the two together. She tells Ruth to dress up in her best clothes and then go to Boaz when he is lying down at the threshing floor. When she arrives, she is to uncover his feet and then lie down — actions that would communicate to Boaz her interest in him.

Ruth follows the instructions, and in the middle of the night, Boaz awakens and discovers his feet uncovered and a woman lying there. Ruth then asks Boaz to cover her with his clothes, which is akin to asking to wear someone’s letterman jacket. Boaz is impressed that Ruth has taken a fancy to him, because he is an older man. But there is a huge problem. Despite their desire to marry, there is a relative more closely related to her former husband, and by law this relative — known as a kinsmen redeemer — has first dibs on Ruth. Boaz vows to settle the matter the next day.

With this sandal I thee wed (Ruth 4)

In the morning, Boaz goes to the city gate, the center of business for an ancient town, and meets with the relative who has the legal right to inherit Elimelech’s land and marry Ruth. Unfortunately for Boaz and Ruth, the relative decides to fulfill his role as kinsmen redeemer by buying the land and marrying Ruth.

All hope seems lost for Boaz’s and Ruth’s love affair when suddenly Boaz informs the man that there is one more catch to the deal: He must take care of the widow Naomi, and the first son born of his union with Ruth must be given the name and inheritance rights of Ruth’s dead husband. This practice, recorded in Deuteronomy 25:7–10, is known as levirate marriage (levir is Latin for “husband’s brother”), and is intended to ensure that someone’s lineage doesn’t die out. The man doesn’t sign up for that deal, and he tells Boaz to go ahead and redeem the property and to marry Ruth. To close the deal with Boaz, the man removes his sandal and hands it to Boaz — a way of guaranteeing a pledge at this time.

Ruth and Boaz marry, and Ruth eventually conceives and bears a son: Obed. Naomi, now too old to bear children, helps raise Obed. In fact, the neighborhood women call the boy the son of Naomi.