Poultry

Poultry is a common item in the food consumption patterns of southerners today, and the regional taste for fried chicken is one that has persisted for many years. Poultry, especially chicken, has served as a regular but supplementary meat to pork, which dominated southern diets during the 1800s and 1900s.

Chicken was most common in the diets of well-to-do farmers and was regarded among the less affluent population as a semiluxury item. It was a popular Sunday dish and was often served to visitors, including the local preacher. Humorous tales about the preacher’s love for chicken abound in both black and white folklore. In addition to fried chicken, among the most popular chicken dishes in the South have been stewed chicken, with the bird slow-cooked until falling apart; chicken pilau or perloo, made with rice and seasoning vegetables (a dish having Mediterranean origins and likely entering the South through Charleston); chicken and dumplings, with the chicken again cooked to pieces and either cornmeal or flour dumplings added at the end; and country captain, a rather exotic dish, with currants, almonds, crisp bacon pieces, rice, and chutney all part of a recipe that is attributed to Savannah for its origins in the South and which has been more common along the Atlantic coast than in the interior.

A glance at cookbooks suggests that southerners have roasted, baked, fried, sautéed, grilled, and barbecued chickens for centuries. Chicken has been a key ingredient in such regional dishes as gumbo, jambalaya, and Brunswick stew. People prize different parts of the chicken, and its neck, liver, heart, feet, and gizzard are all consumed. Cookbooks since the 19th century have also included recipes for wild duck, turkey, and goose, as well as such fowl as blackbird, lark, quail, grouse, guinea fowl, peafowl, pigeon, and other game.

Chickens were kept on practically every farm and often ran loose in the barnyard area. As a result farmers virtually lived with their chicken flock. Chickens could be kept on a minimum of feed and were much more convenient to slaughter and prepare for eating than either pigs or cattle. Predators such as the fox and the hawk were a constant problem for the farmer’s barnyard flock, thus requiring the farmer to keep both his dog and shotgun handy.

Since 1900 the per capita rate of consumption of chicken has increased markedly, outstripping the growth in demand for other meats such as beef and pork. During this period, and especially in recent decades, very important changes have occurred in the production of chickens, and these had an effect on both the economy and culture of the South. A few decades ago the rural population of the South was largely self-sufficient in terms of supplying its chicken and egg needs. Farmers maintained small flocks of chickens for their own use. Often city dwellers’ demand for chickens and eggs was met by farmers who sold excess production to town merchants. This trade furnished butter-and-egg money for farm housewives. Women worked with county extension agents to improve and modernize their production and marketing of eggs and chickens, often setting up roadside stands or selling at special farmers’ markets. Historians credit the profitability of women’s egg and chicken sales with seeing many families through the Depression’s hard times. Today it is rare indeed to find farm families that produce chickens and eggs. In place of this production system have come large-scale, highly specialized mass-production techniques involving the utilization of the latest technological advancements.

This modern era of poultry production dates from the 1930s; its methods had almost totally replaced the previous production techniques by the 1950s. The modern poultry farmer has one or more chicken houses, growing 10,000 to 20,000 birds per house. Ordinarily each batch is grown under contract with large agribusiness firms during a period of 7 to 10 weeks. Market-ready chickens are taken to processing plants for slaughtering, dressing, and packing, and are later transported by refrigerated truck to widely dispersed markets. The poultry industry is characterized by a vertical integration in which an agribusiness firm, either through direct ownership or contract, controls the entire production process. Such firms own processing plants, feed mills, and hatcheries, and contract with farmers to raise the chickens. Because of these arrangements the farmer has little voice in the industry. Some observers label this type of poultry farming a modern version of sharecropping. However, one advantage of this production system to the farmer is that it reduces the capital needed to start poultry farming.

Today a large proportion of southern poultry is produced by farmers who derive only a part of their total income from this source. The chief wage earner may have a full-time industrial or commercial job while the family raises chickens as a supplementary source of income, or chicken farming may be ancillary to other agricultural pursuits. Labor needs of poultry farming are minimal because of the automation of the process. The management of two chicken houses of 10,000 to 20,000 chickens each can usually be accomplished during the evenings and on weekends by family members.

Several of the nation’s main poultry-growing areas are located in the South. Northeast Georgia was one of the first areas to begin large-scale commercial chicken production, with Gainesville serving as a processing plant center and the location for feed mills and hatcheries. Both northeast Georgia and northwest Arkansas began to develop as poultry centers in the late 1930s and early 1940s. They were followed in the 1940s by centers in south central Mississippi and central North Carolina, and in the 1950s by northern Alabama, around Cullman County. Today a trip through these areas provides visible indications of the industry’s impact on the landscape, with the long, narrow chicken houses on farms and the specialized feed trucks and poultry-transport vehicles that operate between feed mills, farms, and processing plants.

The emergence of chicken production in these areas largely reflects changing conditions of traditional subsistence farming. Many of these regions were from the beginning of settlement poor farm areas. They were populated by low-income farm families who had lost a previous source of farm revenue—cotton in northeast Georgia, northern Alabama, and south central Mississippi; tobacco in North Carolina; and fruit in northwest Arkansas. A new source of farm income such as chicken raising was welcomed enthusiastically by these farmers. Local entrepreneurs and agricultural officials were largely instrumental in establishing this industry. J. D. Jewell, for instance, played an important role in establishing production in northeast Georgia. He owned a small feed store in Gainesville in the 1930s and encouraged neighboring farmers to grow chickens, affording him a market outlet for feed and other supplies. Because cash with which to buy baby chicks and feed was seriously limited among farmers, Jewell supplied his customers with credit until their chickens were marketed. However, when the chickens reached the proper age and size for marketing, the farmer had no way to get them to market. Jewell provided transportation to haul the live chickens to urban markets. Later his company became one of the major vertical integrators in northeast Georgia, and he became nationally recognized as an industry leader.

Today southern poultry raisers dominate national chicken production, which all together produced over half of the 8.5 million chickens raised in the nation in 2002. The five leading states are Arkansas, Georgia, Alabama, North Carolina, and Mississippi. Four of the five most profitable chicken companies began in the South: Tyson Foods in Springdale, Ark.; Gold Kist, a farm-cooperative business in Atlanta; Holly Farms in Wilkesboro, N.C.; and Perdue Farms Inc., in Salisbury, Md. Tyson Foods acquired Holly Farms in 1989, acquired diversified food production companies in the 1990s, and solidified its position as the world’s largest poultry producer by merging with Hudson Foods in 1998. Critics have pointed to issues of pollution and inhumane treatment of poultry in this leading agribusiness. Chicken has become the fastest-growing part of the fast-food business, profiting such southern companies as Kentucky Fried Chicken, Church’s Fried Chicken, Popeyes, and Bojangles.

J. DENNIS LORD

University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Karen Davis, Prisoned Chickens, Poisoned Eggs: An Inside Look at the Modern Poultry Industry (1996); J. Fraser Hart, Annals of the Association of American Geographers (December 1980); Sam Bowers Hilliard, Hog Meat and Hoecake: Food Supply in the Old South, 1840–1860 (1972); Lu Ann Jones, Mama Learned Us to Work: Farm Women in the New South (2002); Edward Karpoff, Agricultural Situation (March 1959); N. R. Kleinfield, New York Times (9 December 1984); J. Dennis Lord, “Regional Marketing Patterns and Locational Advantages in the United States Broiler Industry” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Georgia, 1970), Southeastern Geographer (April 1971); Irene A. Moke, Journal of Geography (October 1967); National Agricultural Center, National Poultry Museum, www.poultryscience.org/psapub/pmuseum.html; Malden C. Nesheim, Poultry Production (1979).

Religion and Food

The connection between food and religion runs deep in the southern Bible Belt. Eating has been an incentive for and aspect of going to church for many a southerner. Religious foodways have had a big hand in preserving and signaling change in southern cuisine. In the fellowship of church meals, many southerners feel strong connections to elements that sustain a southern as well as evangelical Christian worldview: the sacredness of family, the providence of God, and the holiness of place. Religious ways of understanding and using food also extend outside religious institutions to express the sacredness of southern culture.

Perhaps the first thing that comes to mind when thinking of southern food and religion is the practice of “dinner on the grounds” after worship. Sharing a potluck meal spread under the trees of the churchyard may have had practical origins in the evangelical camp meetings of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Distances traveled to camp meetings might be almost as long as the sermons; worshippers were encouraged to bring provisions to share. When evangelicals (Methodist, Baptists, and others) established churches, eating “camp meeting style” persisted. After the Civil War, it proliferated and is still observed by many churches today. It is often called by the old name, although the “ground” is now more likely to be the church basement fellowship hall. The popularization of another name, “covered dish supper,” parallels other changes: the evening main meal and the ubiquity of casseroles made with convenience products.

The blessing at a dinner on the grounds, 1940 (Russell Lee, photographer, Library of Congress [LC-USF33-012784-M1], Washington, D.C.)

Practical adaptations keep the church dinner feasible, but the feeling the food evokes ensures its endurance. The church dinner is a type of ritual, a practice that follows the sacred model of a community’s myths or sacred stories. Rituals help to connect the truths of myths to human experience on a basic level through meanings attached to symbols. Food is highly symbolic, and food rituals exist in most religions. They tend to have similar functions, although a tradition might emphasize some functions over others. The dominant evangelical Protestantism of the South is no exception.

Dinner on the grounds, for example, is a type of feast that celebrates the idea of divine blessing on a particular land and people, especially when the foods reflect the bounty of the land. Feasts usually involve sacrifice, the ritual slaughter of an animal that invokes the divine. Overtones of sacrifice remain in church suppers, where game and barbecue are the main dishes.

Ritual meals reaffirm the boundaries of community, as often by the absence of forbidden foods as the presence of special dishes. The teaming of evangelical Protestantism with alcohol prohibitions is such a boundary marker. (It has not gone uncontested in southern Protestantism, however. For example, bourbon whiskey is often attributed to Kentucky Baptist preacher Elijah Craig.) While other traditions might employ alcoholic beverages to connote the sacred (wine in the Catholic Mass), southern Protestantism’s prodigious use of sugar in church meals, from gallons of sweet tea to desserts by the dozens, reflects the special status of these meals as well as the sweet tooth of southern cuisine.

For evangelical Protestants, however, the primary religious functions of church meals follow their theological understanding of Christ’s Last Supper. This is reflected in the parallel meanings of a term they use for the ritual meal in worship, communion, and the term they use to describe what a church meal is, fellowship. Both emphasize the community of believers. Partaking in activities such as church dinners reinforces the bond of community and belonging to the church family. The covered dish supper laid out for everyone to help themselves to food taken from the same pots and eaten at communal tables symbolically relates to the supper at which Christ and his disciples shared common dishes. This points to another function of church meals: commemoration. Christ told his disciples to continue to eat together, “in remembrance of me.” Southern Protestants do this ritually in Communion and in their fellowship meals.

Remembrance and community are reinforced and extended on multiple levels through a variety of foodways that connect church to the rest of life. Church eating can symbolize the bond of community that goes back to early Christians and continues in the local congregation at present. It can remind churchgoers of community here and beyond. Particularly at homecoming celebrations, which center around a dinner on the ground, the idea of ancestral community is reinforced. People who no longer live in the community might return home for the occasion; it might take place in sight of not only the church building but also the church graveyard. A sense of the community’s ancestry is evoked by foods associated with tradition. Cultural myths and food traditions overlap with church rituals—church food is southern food. Churches are among the remaining places where some traditional dishes appear with any regularity. The connections reinforce the holiness associated with both the church and culture of a special people and place.

The two-way flow between church and family is often expressed in food. A big Sunday dinner around grandma’s table is sacred for many southerners, even if experienced more often in nostalgia than in reality. Churches express their family character in foodways that extend into homes. Especially during family transitions or crises, churches nourish bodies and souls alike. Church members take dishes to the homes of grieving families during mourning. After the funeral, a meal might be prepared by church members in the home or fellowship hall. The earliest evangelicals often substituted church family for kin, but the holiness of family for evangelicals today serves as a model for church community. Church meals are now frequently referred to as “family night suppers,” reflecting as much an orientation to families and children as the idea of church as family.

The traditional role of nurturer of home and church assigned to women is foundational for this connection and central to foodways in southern churches. While churchmen may preside over cookouts, church eating has been largely the domain of women. Foodways both reinforce the gender hierarchy and subvert it. While the responsibility for church meals means more labor for women, it also provides opportunities for creative expression. Early church dinners might have been “make do” affairs and still might be depending on supply, money, and time. But even in tough times, church dinners have provided opportunities to celebrate as best one could through special fare. They gave cooks so inclined (or socially pressured) the chance to show off with dishes they might not make for home meals, providing a means for status and recognition. Church foodways also gave leadership and ministerial opportunities to women who were (and often still are) otherwise denied them. Through food events, women have raised money for church causes; enticed men into church participation; fed the hungry, sick, celebrating, and grieving; and acted as “ritual specialists” when they could not preside at the Communion table or preach “the bread of life” from the pulpit.

Churchwomen’s cookbooks have been important sources of fund-raising for their communities. They also preserve a “herstory” of southern Protestantism and a means by which traditions are passed down. While the introduction to the cookbook of the Second Presbyterian Church of Spartanburg, S.C., gives a history of male leadership, the rest of the book documents women’s activity in recipes and anecdotes. Cookbooks can be personal expressions of devotion as well as community legacies. Mrs. Rose Marie Horne, a south Georgia church cook, dedicated her recipe manuscript to “Jesus Christ, my Strength and Sustainer.” When Mrs. Horne became gravely ill, women in her church financed the publication of her book as a testimony to her and to preserve the recipes that had become a part of the church’s life.

Church cookbooks are important sources for charting preservation, innovation, and devolution in southern foodways as well as women’s history. The New Kentucky Home Cookbook, published by Methodist churchwomen in 1884, is a valuable resource on southern white women who did their own cooking. But there is no better way to taste change and continuity in southern eating than to observe (or better, take part in) church meals themselves. A recent project in the Carolinas reveals that church foodways are still meaningful forms of fellowship, with things both lost and gained over time. One mill village church has only 60 members today; but over 300 “came home” to its recent homecoming celebration. The minister, usurping the women’s duty, to some consternation, planned the menu of traditional foods as well as preached. The church maintains itself in part these days by providing space for an after-school meal program. A Holiness church recently employed a dietician to create lighter versions of traditional foods because of health concerns in the African American community. While covered dish suppers have waned in recent years at a suburban Methodist church, a small group eats every Sunday dinner at a southernthemed chain restaurant near the church. And a Baptist church that has grown to megachurch status employs a professional chef who oversees a number of food events and has introduced a popular feature to its Wednesday evening “family meals”: a chocolate fountain in the center of the dining hall.

The dominant evangelicals are not the first or last groups for which the South has provided hospitable ground for the combination of religion and food. Native Americans had a rich ritual life involving foodways. Early Anglicans and Catholics often ate together in homes after services. Foods of religious sects like the Moravians have become part of southern cuisine. Jews in the pork-loving South have managed to maintain foodways that preserve their identity and also reach out to the broader community. Spartanburgers think of a certain typical American coffee cake as “Jewish” because it is a popular item at the local temple’s bake sale. During the annual Greek Festival, Baptists come after “preaching” to eat at St. Nicholas Orthodox Church. The first introduction for many native southerners to the faiths of the growing number of Hindus and Buddhists in the South is through the foods offered at their festivals. And new groups adopt and adapt the covered dish.

Connections between religion and food are not exclusive to the South, but they are particularly prominent in southern culture. Friday night fish fries are accompanied by gospel music in some restaurants. Other eateries offer reduced prices to those who bring their church bulletins to the Sunday dinner buffet. Even when religion is not overtly expressed, the sense of holiness about food carries over in cultural symbols. Southern hospitality parallels fellowship. Fried chicken has symbolic power in part because of its association with Sunday dinners and church suppers. Convenience “bucket” versions play on southern heritage through commercial myths such as Colonel Sanders and PoFolks. Sweet tea and cornbread are “sacraments” for southerners: they commemorate and mark identity with the South. Maybe the best example of a foodway that expresses the connection between religious behavior and southern culture is barbecue. The ritual cooking and eating of a hog commemorates a mythic place and time, communal bond, and identity still sacred in the South.

CORRIE E. NORMAN

Greenville, South Carolina

John Egerton, Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History (1993); Marcie Cohen Ferris, in Southern Jewish History 2 (1998); Jean M. Heriot, Blessed Assurance: Beliefs, Actions, and the Experience of Salvation in a Carolina Baptist Church (1994); Corrie Norman, in Phi Kappa Phi Forum (2002); Wade Clark Roof, in God in the Details: American Religion in Popular Culture, ed. Eric M. Mazur and Kate McCarthy (2001); Daniel Sack, Whitebread Protestants: Food and Religion in American Culture (2000); Janet Theophano, Eat My Words: Reading Women’s Lives through the Cookbooks They Wrote (2002).

Roadside Restaurants

The American roadside restaurant revolution began with the construction of larger factory districts throughout the industrial Northeast. Higher employment concentrations and longer journeys to work brought larger concentrations of potential patrons. Street peddlers purveying ready-to-consume food became more common in urban areas and were joined by horse carts in the 1870s and finally by fixed-location restaurants, most notably diners, along major arterial roads in the 1880s. The diner set the stage for the development of America’s stereotypical roadside restaurant. Few of the thousands of diners scattered across the United States were ever erected in the South, but the only manufacturing company currently producing them is located in Atlanta.

Diners were joined by a new class of “white box” restaurants in the 1920s, most notably the Midwest-based White Castle and White Tower chains. The advantage of the “white box” restaurants was their lower overhead, created by smaller square footage, lower labor demands, and simpler menus. Initially almost always located along streetcar routes within urban areas, these factory-produced units were easily erected and easily moved as traffic patterns changed. White Castle and White Tower located virtually all of their stores in the Industrial Northeast and Midwest, with only a handful in the South. The Krystal chain, however, was created by Rody Davenport of Chattanooga, Tenn., as a conscious copy of White Castle in 1932, and it became a southern icon.

Numerically there were few true roadside restaurants in the South prior to the early 1950s, primarily because of the absence of concentrations of factory jobs and large-scale commuting, a lack of disposable income, and a general antipathy for eating away from home. Drive-ins began appearing in larger southern towns and cities soon after World War II, but in comparison to those in other regions their numbers were small. They were, however, a spawning ground for later regional chains, prominent among them Alex Shoenbaum’s Charleston, W.Va., Parkette Drive-In, begun in 1947, which became Shoney’s in 1953. Other important regional chains from this period include the Krystal clones, Huddle House (Decatur, Ga.) and Waffle House (Avondale Estates, Ga.), as well as the Kettle Restaurants (Houston, Tex.) and Jerry’s (Kentucky).

The numbers, diversity, and locations of roadside restaurants exploded during the 1950s and 1960s. As more Americans found themselves away from home at mealtimes, restaurant dining became commonplace among a larger and larger spectrum of the population. The mobility of the automobile, coupled with the need for a place to park while dining, made suburban locations increasingly attractive, even in small towns. The demand, and then the reality, of the modern roadside restaurant, was born. Fast-food chains are the first of these that come to mind, but actually all kinds of restaurants began appearing at the edges of communities along main roads. Barbecues, cafeterias, chicken shacks, and other locally operated stores saw the opportunity to capture the automobile market outside of the establishment-dominated town center, especially in small and medium-sized cities. While many of the initial stores were franchisee or company outlets of national fast-food chains, tens of thousands were not. Soon it was the old café in downtown that was struggling for survival as the edge-of-town roadside venues began to dominate the restaurant scene.

A “hamburger alley” urban environment was created along the major suburban arterials of virtually every large town in the nation. One might assume that this was the beginning of the end of southern restaurant cuisine. Certainly larger markets have higher percentages of national chain store outlets than smaller ones. All, however, continue to serve a liberal dash of traditional southern fare, though often modified to meet more “national” tastes. A typical such strip might begin with an Applebee’s (national, though founded in Atlanta), then a couple of national sandwich and pizza shops, then a Huddle House and a Sonic (Oklahoma), then a couple of independents, one Chinese and the other serving bagels, followed by two competing chicken fast-food outlets with a barbecue restaurant nestled between them, and so on. The decline of traditional southern fare in the larger roadside restaurant environments has created some backlash, and several chains, most notably Folks (née PoFolks; the two brands now operate separate chains) and Cracker Barrel, have been created to capitalize on this market. An inspection of their customer base reveals that they do not by any means cater exclusively to decrepit southerners. In many ways southern regional culture is being supported today more by incomers than by natives, who often do not comprehend what is being lost. Southern food is one of the most visible areas of this process. Not only are “old timey” ways being supported and reincarnated through fairs and festivals (often organized and supported by the newer residents), but everyday foods are being placed center stage with the patronization of older or creation of newer restaurants featuring traditional southern favorites, though often prepared in ways that your grandmother might have had trouble recognizing as authentic.

RICHARD PILLSBURY

Folly Beach, South Carolina

John A. Jakle and Keith A. Sculle, Fast Food: Roadside Restaurants in the Automobile Age (2002); Richard Pillsbury, From Boarding House to Bistro: The American Restaurant Then and Now (1990).

Social Class and Food

During the early 20th century the South ranked dead last among regions nationally in every conceivable economic category, and when the Great Depression gripped the country in 1929, many southerners grimly joked that they did not notice any difference in their circumstances. In the 1930s President Franklin D. Roosevelt described southern poverty as the most serious economic problem facing America.

At the dawning of the New Deal economic recovery program, the majority of the South’s African American population and about half of its whites subsisted on a hunger diet. “It seems indisputable that the condition of the poor, whether sharecroppers in the black belt, millworkers in the Piedmont, or scratch farmers in Appalachia, began to reach its nadir about 1925,” writes Joe Gray Taylor.

As it had been during much of the South’s past, from the early colonization of Virginia, pork continued to be a mainstay on the region’s tables well into the 20th century, and at the same time a symbol of the inequitable distribution of food products. The phrase “eating high on the hog,” used to describe periods of prosperity, had its converse in the scraps of fatback and gristly ham hocks allocated to slaves for 200 years on the plantations and dispensed to white and black patrons alike at general stores and company commissaries. Pigs have played a central role in southern survival largely because they are one of the most efficient sources of food, as their weight can increase 150-fold in the first eight months of life, and most of the animal is edible.

One of the great paradoxes of the southern table is the fact that African Americans, the southerners subjected to the worst forms of class as well as race discrimination, have made some of the greatest contributions to the region’s cookery. African slaves enriched the diet of the South by introducing products from their homeland such as okra, black-eyed peas, and benne, or sesame, seeds. The kitchen was one of the few places where displaced and enslaved Africans could exercise their creativity, raising common, often even discarded, foods to grandeur. “It is difficult to reconcile the glory of the feast with the ignominy of slavery,” writes John Egerton. Ironies continued after the end of slavery. In the Jim Crow South, from the end of the Civil War into the 1960s, blacks who cooked in restaurant kitchens were not usually allowed to step out front and eat in the dining room. Poverty caused many blacks to be confronted with class deprivation as well as racial oppression. Writer Richard Wright recalls sheer hunger from lack of family resources for food as a child, as well as racial limitations.

The image of the frilly-frocked southern belle, presiding over a table set with silver and porcelain, is a marked contrast to the hard-working lives of so many plantation matrons and especially to the hardscrabble existence of countless southern farm women, who sold eggs to supplement the family income and turned used cotton chicken feed sacks into curtains and clothing. Until recently, the cooking of the aristocratic, planter class was preserved in southern cookbooks, to the exclusion of the marginalized. Most southerners never owned slaves.

Half the poor families in the United States, one-seventh of the white poor and two-thirds of the nonwhite, lived below the Mason-Dixon line as late as 1966. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, the meat in the diet of poor southerners in the Appalachian region consisted largely of fatback—very little bacon or ham—and cornbread or flour biscuits, all low in protein and vitamins, resulting in the proliferation of diseases such as pellagra brought on by nutritional deficiencies. By the end of World War II, milling companies had begun to fortify their flour and cornmeal with vitamins, which brought a significant improvement in the health of southerners.

Amid troubles and triumphs, economically disadvantaged southerners of all races have resourcefully combined the lowliest of foodstuffs—the simple fare of field and farm—to create some of America’s most memorable dishes: lard-seasoned soup beans and cornbread flecked with pork cracklings; redeye gravy, a simple combination of grease, water, and perhaps some leftover coffee; and pain perdu, “lost bread” or “French toast,” an ingenious way of using leftover bread as dessert, perked up with precious sugar and spices. Hard times resulted in clever ways to preserve meat, vegetables, and fruit. Country hams, cured with salt and smoke, apples boiled down into apple butter, and green beans strung and dried as “leather britches” all grew out of necessity.

Southerners have pickled watermelon rinds, made wine out of corn cobs, stewed mudbugs, killed spring lettuce with vinegar and bacon grease, and sautéed dandelion greens, thereby creating America’s most diverse indigenous cuisine, appreciated all the more because of the hardships from whence it has come.

FRED W. SAUCEMAN

East Tennessee State University

John Egerton, Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History (1987); Lu Ann Jones, Mama Learned Us to Work: Farm Women in the New South (2002); Joe Gray Taylor, Eating, Drinking, and Visiting in the South: An Informal History (1982).

Soul Food

ORIGINS. Popularized in the 1960s, the term soul food is a political construct, a renaming and reclaiming of the traditional foods of African Americans, the foods of historical privation, by African Americans. Common usage of the term escalated in the late 1960s when soul music was in vogue and Black Power was touted.

Chicken and fish rolled in meal or batter and deep fried, greens and cowpeas boiled with pork and served with pot liquor, okra cooked to a low gravy, sweet potatoes baked to a golden brown, and cornbread in many varieties form the basis of a quasi-ethnic cuisine whose roots are, arguably, as African as they are American. Maize and sweet potatoes were taken from America to Africa by Portuguese traders in the 16th century, and peas of the black-eyed type have been eaten in Africa for some 400 years. Even specialized local cuisines with identifiable European roots, such as French cooking in Louisiana, have been greatly influenced by African taste in such things as the heavy use of red pepper and the creation of dishes like gumbo based on ingredients, such as okra, that came from Africa. In fact, the black presence may explain why foods like maize and cowpeas, which can grow anywhere in America and were taken into the American frontiers, remain staple foods only in the South, aside from those areas of the Southwest where they were staple foods of Native Americans. Some scholars see Native American influences in soul food as well.

POPULARIZATION.

In March 1970 Vogue published an essay by Gene Baro that took notice of the newest food fad sweeping the land, observing that “the cult of soul food is a form of black self-awareness and, to a lesser degree, of white sympathy for the black drive to self-reliance. It is as if those who ate the beans and greens of necessity in the cabin doorways were brought into communion with those who, not having to, eat those foods voluntarily now as a sacrament.”

Baro was not the first to plumb the deeper meaning of this exotic cuisine. In November 1968 Craig Claiborne, the Mississippi-born New York Times restaurant critic, had written a column praising the chitlins and champagne offered at Red Rooster’s in Harlem, and soon the droves descended, tongues wagging, upturned noses sniffing out the heady scent of long-simmered swine intestines. Esquire had taken notice of the soul food craze eight months earlier. Seventeen magazine ran a feature soon after Claiborne’s article. Time followed in March 1969, McCall’s in September of the same year. Most articles purported to be soul food primers for the trend-conscious white consumer.

Some were condescending. “The big question is why soul food is so popular,” observed an unnamed writer for Time. “It is cheap, simple fare that reflects the tawdry poverty of its origins. Soul food is often fatty, overcooked, and underseasoned. Considering the tastelessness of the cuisine, the soul food fad seems certain to be fairly short-lived. For many Negroes, it is long since over; it ended, in fact, as soon as they could afford better food.” An African American advertising copywriter observed, “White men are too much. Here we are, trying to live the way they do, and what happens? They get themselves beads and shades and go out and dance the boogaloo.”

By 1970 at least 15 soul food cookbooks had been published, including Cooking with Soul by Ethel Brown Hearon, A Pinch of Soul by Pearl Bowser, and the Soul Power Cookbook from the Lane Magazine Company. Most of the books included an explanatory essay of some sort. “Soul food grew in the way that soul music grew—out of necessity, out of the need to express the ‘group soul,’” wrote Bowser. “Originally, of course, the need was to keep alive in spite of the paucity of scraps and the sometimes unsavoriness of the leftovers. Somehow, in transforming such things as animal fodder into rich peanut soup or wild plants into some of our favorite and tastiest vegetable dishes, there grew a pride—a pride in ingenuity and a pride in producing ‘our own thing.’”

Some African Americans dismissed it all as a matter of misplaced sentimentality. “In the sixties, the young people in the cities were missing something they thought was in the South,” said Edna Lewis, the grand doyenne of African American chefs. “They coined the term soul food and nobody challenged it.”

By 1972 soul food was moving upscale as restaurants like Atlanta’s Soul on Top o’ Peachtree opened downtown. But, like the fondue fad of a few years before or the Cajun craze that would dawn some years later, soul food was soon banished to the back of the national cupboard. By October 1973 Soul on Top o’ Peachtree closed. According to an article in the Atlanta Constitution, “Although the restaurant promised to be a fashionable place to purchase barbecue, greens, pig feet, and other ‘soul food’ dishes, the best selling meal in the house had an Italian flavor.” Said proprietor Willie Stafford, “We had a $1.35 special on spaghetti and meatballs. We sure sold a lot of that stuff.”

In Native Son, originally published in 1940, Richard Wright describes a pilgrimage from Chicago’s wealthy white suburbs to the south side of the city where expatriate black southerners had been making their home since the early years of the Great Migration. Along for the ride are the black protagonist, Bigger Thomas, and two young whites, Jan, an earnest, clueless Communist, and his girlfriend, Mary, daughter of Bigger’s employer. “Say Bigger, where can we get a good meal on the South Side?” asks Jan. “We want to go to a real place,” says Mary. “Look Bigger. We want one of those places where colored people eat, not one of those show places,” insists Jan. Bigger ponders this for a moment and then offers, “Well, there’s Ernie’s Kitchen Shack.” And soon they’re barreling down South 47th Street in search of honest-to-goodness, skillet-fried chicken.

NOUVEAU.

In the new millennium, when the term soul affectionately may describe a talented country-western singer or may be employed by a theater company to convey that their hot new show is nurturing, satisfying, and comforting, the label has lost some of its relevance. The African American culinary frontier has expanded so that soul no longer wholly characterizes the cultural and social choices made by people of color in this country.

Of course, the traditional dishes and recipes of old can still be found—slowly cooked and highly seasoned greens, beans, and other fresh vegetables; macaroni and cheese; sweet potatoes in many forms; pork in all its manifestations; chicken; hot bread; sweet tea; cobbler; and so on. But the make-do nature of soul food has been morphing in recent years. In a time of rising middle-class values and improving social conditions, it was perhaps inevitable that a “new” style of southern and soul cooking would emerge—leaner cuts of meat, lighter styles of cooking and seasoning, an emphasis on health and nutrition.

But unlike New Southern Cuisine, with its emphasis upon comparatively exotic ingredients and innovative cooking methods, the Soul Food Revival, as the trend has been called, in a more realistic sense, exemplifies culinary freedom. Contemporary African American cooks are liberated from the association with the survival foods of the slave kitchen. Many restaurants now prefer terms like home-style, southern-style, even Mama’s cooking. Many have moved uptown. At home, dinner often resembles the healthier, more vibrant cooking of African American farm cooks, such as that of cookbook author Edna Lewis.

In her 1988 book In Pursuit of Flavor, Lewis dared to step outside the narrow confines of soul food and redefined the African American woman in the kitchen. She revealed a culinary grace not often associated with the culture, cooking sweet potatoes with lemon, boiling corn in the husk, seasoning with fresh herbs.

Lewis and her peers dismissed the idea that poverty food defined African Americans. They emancipated a generation of new African American cooks. As a consequence, new African American cooking may have lost its “soul” but not its spirit of experimentation and originality.

MARGARET JONES BOLSTERLI

University of Arkansas

TONI TIPTON-MARTIN

Austin, Texas

JOHN T. EDGE

University of Mississippi

Sheila Ferguson, Soul Food: Classic Cuisine from the Deep South (1993); Eugene D. Genovese, Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made (1976); Jessica B. Harris, The Welcome Table: African American Heritage Cooking (1995); Bob Jeffries, Soul Food Cookbook (1970); Bruce F. Johnston, The Staple Food Economies of Western Tropical Africa (1958); Helen Mendes, The African Heritage Cookbook (1971); National Council of Negro Women, The Black Family Reunion Cookbook: Recipes and Food Memories (1993); Curtis Parker, The Lost Art of Scratch Cooking: Recipes from the Kitchen of Natha Adkins Parker (1997); Carolyn Quick Tillery, The African-American Heritage Cookbook: Traditional Recipes and Fond Remembrances from Alabama’s Renowned Tuskegee Institute (1997); Joyce White, Brown Sugar: Soul Food Desserts from Family and Friends (2003), Soul Food: Recipes and Reflections from African-American Churches (1998); Sylvia Woods, Sylvia’s Family Soul Food Cookbook: From Hemingway, South Carolina, to Harlem (1999), Sylvia’s Soul Food (1992).

Aunt Jemima

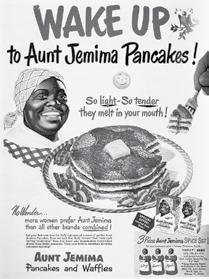

Although the brand that Aunt Jemima represents has never been based in the South, this controversial spokes-character and cultural icon was originally based on a freed slave named Nancy Green, born in Montgomery County, Ky., in 1834.

In 1889 Chris Rutt and Charles Underwood of St. Joseph, Mo., bought the Pearl Milling Company and developed the first ready-mix pancake flour. After hearing a performer wearing blackface, an apron, and a bandana headband sing a tune called “Old Aunt Jemima” at a vaudeville show, Rutt decided that he had found the perfect name for his and Underwood’s new pancake mix. The following year they suffered financial difficulties and sold their formula to R. T. Davis and the Davis Milling Company. Davis, looking for a unique way to advertise his newly acquired product, discovered the warm and friendly Nancy Green working for a judge in Chicago and decided to bring the character of Aunt Jemima to life. The famous original Aunt Jemima image, painted by A. B. Frost, was based on Green’s likeness.

At the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Davis Milling constructed the world’s largest flour barrel, and Nancy Green, as the vaudeville-inspired Aunt Jemima, demonstrated the pancake mix, making and serving thousands of pancakes and selling over 50,000 orders for the mix. Fair organizers were so impressed with Green in her role of Aunt Jemima that they declared her the “Pancake Queen.” For the next several years Davis and Green traveled the country promoting the pancake mix, their imminent arrival in towns often well advertised and highly anticipated. Nancy Green played the role of Aunt Jemima for 30 years, until her death in a car accident in Chicago in 1923.

Aunt Jemima pancake mix advertisement, c. 1950 (Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.)

In 1926 Davis sold his company to Quaker Oats, and in 1933 Quaker decided to bring Aunt Jemima back to life. They hired Anna Robinson, “a large, gregarious woman with the face of an angel,” who traveled the country promoting the character until 1951. Her popularity continually increased, and from the mid-1950s until the late 1960s Disneyland boasted its own Aunt Jemima–themed restaurants. Aylene Lewis portrayed the character at the Aunt Jemima Pancake House from 1955 to 1962 and at the Aunt Jemima Kitchen from 1962 to 1969. Pancakes were no longer just for breakfast.

Over the decades, dozens of women donned Aunt Jemima’s bandana in promoting and demonstrating the pancake mix across the country, but the product’s packaging changed little. Aunt Jemima always wore the bandana and apron, and in person she spoke in dialect, sang songs, and told tales about the Old South. A typical 1920s advertisement portrays Aunt Jemima as a slave woman standing in the doorway of her cabin admiring a tall stack of pancakes. The copy reads, “Doesn’t it make you think of Mark Twain’s boyhood, and of Aunt Jemima, too, in her plantation cabin?” Unsurprisingly, African Americans objected to the stereotype, claiming that it was a glorification of slavery and a painful reminder of the occupational segregation that relegated a large percentage of black women to domestic service. Eventually the name “Aunt Jemima” came to represent something derogatory, akin to a female Uncle Tom.

In 1989, in an attempt to quell cries of racism and calls to discontinue use of their trademark character, the Quaker Oats Company modernized the image of Aunt Jemima from the stereotypical plump and jolly Gone with the Wind mammy character to a slimmer, lighter-skinned woman who wears pearl earrings and has a perm. Nevertheless, today’s made-over Aunt Jemima continues to invite debate and controversy. While some argue that antipathy toward the character is no longer warranted, others continue to consider the character a symbol of racial prejudice and social injustice.

JAMES G. THOMAS JR.

University of Mississippi

Ronnie Crocker, Houston Chronicle (5 April 1996); Grace Elizabeth Hale, Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940 (1999); Marilyn Kern-Foxworth, Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, and Rastus: Blacks in Advertising, Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow (1994); M. M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (1998); Diane Roberts, The Myth of Aunt Jemima: Representations of Race and Region (1994).

Barbecue, Carolinas

When two Carolinians meet for the first time, typically they exchange three important pieces of information: church attended, basketball team embraced, and kind of barbecue eaten. Religion and sports affiliations may be minor differences, but barbecue styles are schisms. One commonality exists: barbecue is pork. The differences come down to a few essential points: which part of the pig contributed the meat, how finely is the meat chopped, and what barbecue sauce was sprinkled into it as it was chopped.

In eastern North Carolina, in the belt centered around Wilson, barbecue means meat from the whole pig. The slow-cooked meat is chopped fine, almost minced, and dressed with a sauce made from vinegar and red pepper. The flavor is as distinctly eastern Carolina as are tobacco sheds.

In western North Carolina, around Lexington and Shelby, the meat comes from the shoulder. It is chopped more coarsely, almost shredded, then dressed with a sauce made from vinegar, red pepper, and a little tomato, usually from ketchup. In South Carolina, there are pockets, centering around Columbia, that use a mustard-based barbecue sauce, but in most of South Carolina, one will find variations of the same two styles that prevail in North Carolina.

Barbecue in the Carolinas rarely if ever involves sauce on the meat as it cooks. Cooks may use a dry rub, or maybe a simple wet mop dabbed on the meat to keep it from drying out. The meat is the key, slow-cooked to sweet succulence, then dressed simply with dashes of vinegary sauce. Sandwiches are usually topped with coleslaw, often mixed with more barbecue sauce. Plates often come with some form of stew as a side dish, Brunswick stew in North Carolina, barbecue hash in some parts of South Carolina. Hush puppies are often elemental, and the iced tea is sweet.

There has been a lot of migration among these styles, of course. Cities like Charlotte and Raleigh have eastern-and Lexington-style restaurants and devoted fans of each. The 20th century saw Carolinians moving from farms to towns for factory and mill jobs, and their barbecue styles followed.

But why did the eastern and western areas of the state evolve such distinct styles? One finds little conclusive evidence, but theories abound. The eastern part of the state was settled much earlier, so its sauce style may date to a colonial era preference for sour, piquant tastes. In a 1995 issue of Food History News, Clarissa Dillon sites 18th-century letters and other written references from several spots in the South that describe barbecue as a cooked pig basted with wine, lemon juice, and spices—with never a mention of tomatoes. Kay Moss, of the Schiele Museum in Gastonia, N.C., suggests that tomatoes came late to the American diet, after the eastern barbecue style had become established. Moss found an 18th-century recipe from the Stockton family that specified pork, basted only with butter and pepper, but most early versions she has found describe a sauce of wine, lemon juice, sage, red and black pepper, and salt.

For the more modern Lexington-style barbecue, a firm genealogy dates to about 1920. Bob Garner tells the story of how a man named Jess Swicegood opened a barbecue stand in Lexington. A teenager named Warner Stamey took a job helping Swicegood. Stamey later sold barbecue in Shelby and Lexington and eventually opened Stamey’s in Greensboro. Among other claims to fame, Warner Stamey is believed to have been the first person to add hush puppies, a fish camp standard, to the chopped barbecue plate. Stamey trained his brother-in-law, Alston Bridges, who opened a restaurant in Shelby that still bears his name. Another employee was Red Bridges (no relation to Alston but the source of endless confusion in the barbecue world), whose descendants still run Bridges’s Barbecue Lodge in Shelby. And in the 1950s, Stamey employed a young Wayne Monk, who is now the best-known restaurant owner in pit-crazy Lexington, site of the annual Lexington Barbecue Festival.

In the Carolinas the barbecue business is a business. Church barbecues and family reunion pig pickin’s are still held (though nowadays they are often catered), and people do cook barbecue at home in small batches, usually involving a half-shoulder—a Boston butt—cooked in the oven or on a kettle grill. But true barbecue requires hours of slow-cooking over a wood fire, a hot, smoky affair, and most Carolinians leave the work to restaurants. People are as loyal to their favorite places as they are to their college teams, and routes to the beach are chosen based on which restaurant one wants to pass. Landmark barbecue restaurants such as the Skylight Inn in Ayden, Allen & Son in Chapel Hill, and Parker’s in Wilson are fixtures of their part of the culinary South.

KATHLEEN PURVIS

Charlotte Observer

Jim Auchmutey and Susan Puckett, The Ultimate Barbecue Sauce Cookbook (1995); Rick Browne and Jack Bettridge, Barbecue America: A Pilgrimage in Search of America’s Best Barbecue (1999); John Egerton, Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History (1987); Lolis Eric Elie, Smokestack Lightning: Adventures in the Heart of Barbecue Country (1996); Bob Garner, North Carolina Barbecue: Flavored by Time (1996); John Thorne and Matt Lewis Thorne, Serious Pig: An American Cook in Search of His Roots (1996).

Barbecue, Memphis and Tennessee

When it comes to Memphis barbecue, it’s all about the pig—preferably pulled and piled on a sandwich, topped with sauce and slaw, and served with a glass of sweet tea. Some Memphis restaurants offer beef brisket, smoked chicken, even the rare “vegetarian” barbecue (a Portobello mushroom sandwich at Central BBQ), but those dishes are like the Filet-O-Fish on a McDonald’s menu, a postscript to the main attraction—the pulled pork sandwich, which is the state’s very own Big Mac.

Memphis proclaims itself the center of the barbecue universe. It is likely one of the few cities on the planet where one can consume barbecue for breakfast (at the more than 10 Tops locations, which open at 9 A.M. or earlier). “Once you get 50 miles away from Memphis, there’s no such thing as barbecue,” said Nick Vergos, part of the city’s first family of barbecue, whose father, Charlie Vergos, opened the “world famous” Rendezvous in the early 1960s. Veteran restaurateur Walker Taylor, who has been serving barbecue at the Germantown Commissary for more than 25 years, casts a wider net. “You can get good Memphisstyle barbecue in a one-hundred-mile radius,” said Taylor, who jokingly referred to this territory as “The Ring of Fire.”

John Egerton offers yet another view of the state’s barbecue boundary, as the section of the state “that includes the area north of Jackson and around Dyersburg. It extends into parts of Arkansas and Kentucky,” he said. “There are, of course, exceptions to the rule, but that’s barbecue country to me.”

In Memphis—home of the world’s largest pork barbecue cooking contest, held on the banks of the Mississippi River every May—the passion for pig goes way back. According to a 1989 story in the Commercial Appeal, historian Ed Williams, with tongue in cheek, traced the region’s first pig roast back to the 1500s: “When Hernando de Soto landed in Florida in May, 1539, he had with him six hundred men, two women, three hundred and twenty-seven horses, and a herd of pigs. For two years, the Spaniards explored the southeastern United States, and the pigs multiplied. One night, in 1541, a surprise Indian attack set fire to the Spanish camp somewhere south of the Chickasaw Bluff, and most of the hogs were burned to death. It may have been the first time the smell of barbecue wafted over the Mid-South.”

Little Pigs Barbecue, Memphis, Tenn. (Courtesy Amy Evans, photographer)

Leonard’s, among the city’s first barbecue restaurants, opened in 1922, borrowing cooking techniques from the area’s African American backyard barbecuers who cooked in old bathtubs or in pits dug into the ground. “It all started around Brownsville, a hotbed for barbecue in the heart of an agricultural area,” said Taylor, who turned his family’s country store into the Germantown Commissary. “The reason people in that area cooked shoulder was because it was cheap.” The shoulder turned out to be a perfect fit for long, slow cooking over the embers of a hickory fire. “It’s got that plate on the bottom, and a layer of skin that protected the meat,” Taylor said. “It works like a piece of aluminum foil.”

Shoulders were often cooked 8 to 12 hours before the meat was tender enough to pull off the bone, chop, and pile onto a sandwich. Cooking times vary widely now, as the average size of hogs has ballooned over the years. “We used to have a local slaughterhouse until about four years ago,” Taylor said. “You would get a thirteen- to fifteenpound shoulder that would sit nicely over the pit. Those days are over. Now, there are three or four major producers and shoulders are seventeen to twenty pounds.”

The debut of the überhog is not the only recent development in the barbecue business. An increasing number of restaurants are turning to gas-powered cookers. They work on the same principle of cooking the meat at a low temperature for an extended period, with a separate burn box where smoldering wood smoke filters into the meat cooking on rotisserie racks. While advocates cheer this as a technological advance, barbecue purists are not convinced. In his 1996 book Smokestack Lightening Lolis Eric Elie describes “the mediocre barbecue we’ve endured in Memphis, meat with all the flavor of boiled cotton,” to that produced by a seasoned pitmaster he finds in the country. “They say they have barbecue, but they don’t have a thing in the world but baked meat with barbecue sauce on it,” muses Billy Anderson of Anderson’s Bar-B-Que in Lexington, Tenn.

Walker Taylor explains that the Germantown Commissary installed a Southern Pride cooker because the small kitchen couldn’t handle the increasing volume of business with its traditional pit. “If I was only doing eight or ten shoulders a day, I would do it, but I would burn this place down if I cooked everything on the pit.”

One of the city’s most recognizable barbecue restaurants goes against the “low-and-slow” grain altogether and cooks its ribs over the direct heat generated by hardwood charcoal. “We don’t call it barbecue. We call them charcoalbroiled ribs,” said Nick Vergos, who runs the shipping part of the business, sending pork all over the country. “But then, is the guy who bakes his meat and puts sauce on it and calls it barbecue more barbecue than ours?”

Vergos’s father’s original restaurant served ham sandwiches and added ribs to the menu at the suggestion of a savvy meat salesman. “Mr. Fineberg brought my father some loin ribs and convinced him to try them,” Vergos recounted the often-told history. “He had a waiter named Lil’ John who said every barbecue he had ever eaten used vinegar. They didn’t have any vinegar, but they did have pickles, so they used some diluted pickle juice to baste the meat.”

The first batch didn’t have much flavor, so the elder Vergos experimented with sprinkling the ribs with spices he had in the kitchen for his signature chili. And the dry-rub rack of ribs was born. For many, especially people outside the region, those dry ribs epitomize Memphis barbecue. Daisy May’s BBQ USA in Manhattan touts its Memphis-style dry ribs, for instance.

Whether it’s ribs or a chopped shoulder sandwich, sauce is used sparingly, or served on the side. The tomato-based sauces balance sweet and tangy and are often spiked with liquid smoke. Some barbecue restaurants in the Memphis area offer a hot sauce option, which is closer to the thin, vinegar-based sauces of North Carolina, but with a fiery kick.

Barbecue contest champion John Willingham writes in his cookbook, John Willingham’s World Champion Bar-B-Q, “I am convinced that sauce was invented to cover up mistakes in cooking. . . . I, however, serve my sauces on the side only.” Willingham, a Shelby County commissioner who operated a barbecue restaurant for several years, offers up his signature recipe that calls for tomato sauce, Coke, cider vinegar, chili sauce, steak sauce, lemon juice, dark brown sugar, soy sauce, and a host of spices.

Many restaurants have turned their sauces into side businesses. The Bar-B-Q Shop, which sells its sauce under the “Dancing Pigs” label, was singled out as having the country’s best vinegar-based barbecue sauce during Chili Pepper magazine’s 2005 Fiery Food challenge. Coleslaw, typically finished with a mayonnaise-based dressing, is the cool yang to the sauce’s yin on a shoulder sandwich. Slaw preparations vary widely in texture and taste, from minced to shredded, and from sweet to the savory mustard slaw found at Payne’s on Lamar—not to be confused with the Payne’s on Elvis Presley Boulevard.

At Mary’s Old-Fashioned Pit Barbeque in Nashville, pickles stand in for slaw. That shredded cabbage salad is an option, but costs extra. The pulled pork sandwich at Mary’s shows its regional colors in another respect: it’s offered on either the standard hamburger bun or on savory cornmeal cakes.

The atmosphere at restaurants in Tennessee barbecue country varies as much as coleslaw recipes. While some customers insist that the best barbecue is found at out-of-the-way holes-in-the-wall, full-service restaurants such as Corky’s offer a casual dining experience and drive-through service. Many diners have made personal connections with the boisterous crew of waiters at the Rendezvous, where the minimum tenure of most members of the wait staff is 20 years.

After gnawing through racks of ribs or tackling wonderfully messy pulled pork sandwiches, diners face another challenge at the end of the meal. With the exception of the Rendezvous, which does not offer anything sweet, Memphis barbecue restaurants tempt customers with caramel cakes, banana pudding, fried pies, and, at the Germantown Commissary, fresh-baked coconut cream and lemon meringue pies, which have been made by the same woman for the past 18 years.

LESLIE KELLY

Memphis, Tennessee

John T. Edge, Southern Belly: The Ultimate Food Lover’s Companion to the South (2000); John Egerton, Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History (1987); Lolis Eric Elie, Smokestack Lightning: Adventures in the Heart of Barbecue Country (2005); Jeffrey Steingarten, The Man Who Ate Everything: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know About Food, but Were Afraid to Ask (1999).

Barbecue, Texas

Like nearly everything else associated with the Lone Star State, Texas barbecue is stereotyped. The common assumption is that southern barbecue is slow-cooked pork and that Texas barbecue is slow-cooked beef. There is at least a grain of truth in that image—pork generally dominates barbecue in the Southeast, and beef often is the centerpiece of barbecue in the Southwest—but the history and culture of Texas (and its barbecue) are much more interesting and complex than the cowboy and beef cattle stereotype that throws such a long mythic shadow over all aspects of Texas, including its foodways.

Texas is a geographic and cultural crossroads, the site of a complex convergence of traditions where the Southeast meets the Southwest, where the southern plantations of east Texas encounter the ranches of south and west Texas, and where an ethnically diverse Texas culture shares an international border with Mexico. The music, food, and lifestyles of American Indians, Anglo Americans, African Americans, Mexican Americans, and numerous immigrant groups—Germans, Czechs, Cajuns, among many others—came to Texas from every direction, encountered each other, and for centuries have been sharing (and sometimes fighting over) land, legal systems, politics, music, and food. No place is more reflective of that convergence than central Texas, an area surrounding the state capital of Austin by about 75 miles in every direction that appropriately has been called the Texas Barbecue Belt.

The foodways that historically came together in Texas formed a rich mélange of regional cuisines, including most notably Mexican (or “Tex-Mex”) food and barbecue. Because it has so many sources, Texas barbecue involves a wide array of meats (beef, pork, mutton, cabrito or kid goat, sausage, and chicken, among others), preparations (including dry rubs, wet mops, tomatobased sauce, vinegar-based sauce, and no sauce), woods (oak, hickory, mesquite, and more) and side dishes, drinks, and desserts that commonly go with it. Despite the many cultural sources and differences, all Texas barbecue traditions have one thing in common: meat (often beef) that has been slow-cooked over indirect heat and wood smoke, although sometimes grilling directly over coals is a component of the slow-cooking process, especially in cowboy cooking. It is also a given that the social scene that revolves around the all-day cooking and eating is referred to as “a barbecue.” Although barbecue has become a staple of Texas’s restaurant industry, and barbecue cookoffs and eating contests are now widespread in Texas, barbecues also are often special cultural events such as family reunions and political gatherings. In 1860 Sam Houston spoke at “The Great American Barbecue,” a major political rally, and nearly a century later, in 1941, Governor W. Lee “Pappy” O’Daniel threw a free barbecue on the grounds of the governor’s mansion to celebrate his inauguration. Some 20,000 Texans showed up to consume 6,000 pounds of barbecued beef, in addition to mutton, chicken, a half ton of potato salad, and all the fixin’s, plus one barbecued buffalo killed by Pappy himself for the occasion. U.S. president Lyndon B. Johnson held many barbecues for world leaders at his ranch on the banks of the Pedernales River in the central Texas Hill Country.

Barbecue came to Texas as part of the cultural baggage of southern Anglo Americans and African Americans who brought with them barbecue traditions that had been noted in the colonial South as early as the 17th and 18th centuries. In his 1705 history of Virginia, planter Robert Beverley discussed the “Barbacueing” that had been picked up from local natives, and George Washington later in the century wrote about attending and giving barbecues. The term itself—barbecue in English or barbacoa in Spanish—is a phonetic pronunciation of the Indian term barbracot, which refers to the raised wooden grill set up over a bed of coals to smoke and slow-cook meats in the Caribbean and on the North American mainland. Beginning in the 1600s, southern Anglo American colonists and African American slaves picked up this tradition from Indians in the New World and raised it to a culinary art and well-known social institution in the American South. While these barbecue traditions were developing across the South, Spanish and French adventurers in the part of colonial Spanish Mexico that would become Texas were contacting Indians who had included the grilling and smoking of meat in their traditions for centuries. When La Salle was establishing a French presence in Spanish Texas in the 1680s, he and his colleagues often hunted buffalo, then roasted and smoked the meat in pits, even commenting that the meat “had a much better taste” than that found in France. By the time Anglo Americans and their African American slaves left the South for Mexican Texas in the 1820s and 1830s, they took with them various barbecue traditions, many based on pork, a staple of the southern diet, including that of poor whites, slaves, yeoman farmers, and plantation owners alike. African Americans were often the cooks on plantations that dominated some areas of the South, including parts of east Texas, and African American barbecuing has remained a component of southern and Texas barbecue to this day.

By the end of the Civil War the Anglo Americans in Texas had merged their southern cow herding traditions with the vaquero ranching traditions of Spanish Mexico to form the American cowboy way of life based on driving surplus longhorn beef cattle to distant markets. Southern barbecue and Mexican barbacoa cooking traditions combined in outdoor cowboy cooking in pits and over coals. As a result of the proliferation of cattle in Texas and eventually across the nation, beef assumed a new importance, joining pork as a staple in many people’s diets. Captain Flack, a famous frontier hunter, noted that it was common in mid-19th century Texas to hunt wild longhorn cattle along with deer, and that people would gladly use the meat. Adding to this mid-19th-century cultural mix were Texas’s many immigrant groups, including large numbers of Germans and Czechs who settled in the central Texas region, bringing with them their traditions of sausage making and smoked meats.

Over the next 100 years the convergence of southern barbecue traditions with Texas’s Spanish/Mexicanin-fluenced cattle culture and European ethnic foodways led to the classic barbecue meal found in the central Texas Barbecue Belt in the early 21st century: slow-cooked and smoked beef brisket, sausage, and ribs, with a variety of sauces for pouring or dipping, plus the now-traditional side dishes of potato salad, coleslaw, pinto beans, pickles, and onions. Iced tea, soda, and beer are the usual drinks, and there is often a stack of squishy white bread slices with which to make a “sausage wrap” or a sliced beef sandwich or to use for sopping the plate. A few barbecue restaurants stubbornly still serve only meat, with no side dishes, reflecting their origins as meat markets and butcher shops in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Especially in the years since World War II, many meat markets serving leftover smoked meats as a sideline evolved into full-fledged barbecue restaurants with side dishes and sit-down dining. Although there are a few successful barbecue restaurant chains, most well-regarded barbecue places are mom-and-pop joints in the form of a roadside stand, a small house on a city street, or a sprawling suburban restaurant. The slow-cooking involved in most barbecue simply defies the approach that makes fast-food restaurants successful.

Three sites widely regarded as the holy trinity of central Texas barbecue joints are Louis Mueller’s (pronounced Miller) Barbecue in Taylor, Kreuz (pronounced Krites) Market in Lockhart, and Cooper’s Old Time Pit Bar-B-Que in Llano. All three are located in towns that think of themselves as the barbecue capital of Texas, and all three have family histories that have led to competing branches and sometimes family feuds that are of great interest to barbecue fans. They also reveal much about the German, meat market, and cowboy roots of Texas barbecue as it evolved beyond its predominately southeastern origins. Mueller’s has a coarse-grained German “hot gut” sausage in addition to other meats; Kreuz’s serves only meat on butcher paper (although it has added a few side dishes in recent years); and Cooper’s enormous pits in the parking lot feature less smoking and more grilling in the cowboy tradition of cooking directly over coals. The many Mikeska brothers, sometimes referred to as the first family of Texas barbecue, have run barbecue joints in towns sprinkled all over central Texas for several generations. Despite the tight family connection, the menus, sauces, and meats are different in every Mikeska restaurant, illustrating the many differences in barbecue wherever it is found from joint to joint, town to town, and region to region throughout Texas and the rest of Barbecue Nation. There are many disputes about Texas barbecue as a result of its diverse cultural roots, but there is no doubt that it is a beloved culinary tradition and a nearly sacred meal served at some of the most important moments in the private and public lives of Texans.

GEORGE B. WARD

Austin, Texas

T. Lindsey Baker, in Juneteenth Texas: Essays in African-American Folklore, ed. Francis E. Abernethy (1996); Robert Beverley, The History and Present State of Virginia, ed. Louis B. Wright (1947); Bill Crawford, Please Pass the Biscuits, Pappy: Pictures of Governor W. Lee O’Daniel (2004); J. Frank Dobie, The Longhorns (2000); David Hackett Fischer, Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America (1989); William C. Foster, ed., The La Salle Expedition to Texas: The Journal of Henri Joutel, 1684–1687 (1998); Ernestine Sewell Linck and Joyce Gibson Roach, Eats: A Folk History of Texas Foods (1989); Jack Jackson, Los Mesteños: Spanish Ranching in Texas, 1721–1821 (1986); Terry C. Jordan, Trails to Texas: Southern Roots of Western Cattle Ranching (1981); W. W. Newcomb Jr., The Indians of Texas: From Prehistoric to Modern Times (1961); Robb Walsh, Legends of Texas Barbecue Cookbook: Recipes and Recollections from the Pit Bosses (2002).

Beans for sale at a farmers’ market (Bill Tarpenning, photographer, United States Department of Agriculture)

Beans

Beans have been a mainstay of the southern table since long before European settlement. Fresh from the garden, dried, canned, or frozen, they have sustained the South for centuries.

The signature dish of the mountain South is a bowl of soup beans, with a wedge of hot cornbread and a slice of onion. Although most beans yield a flavorful soup, in southern Appalachia, pintos are the legume of choice, simmered in water and seasoned with pork. In times when meat was scarce, neighbors often passed hunks of pork among themselves to season their beans, until all the flavor was cooked out of this “community sinker.”

Green beans, strung and broken into washpans on southern porches, are one of the most common side dishes all through the region. They, too, are typically cooked slowly, with pork side meat, until the beans are quite soft, usually about two hours. When new potatoes are freshly dug, cooks add them for the second hour. Half-runners and Kentucky Wonders are favorite varieties of green beans, staked in the garden with cane poles and tied with twine. The term mess of beans is used to describe the harvest and is a vague form of measurement that indicates roughly the amount of beans required to feed one’s family. Before canning techniques were taught throughout the mountains by home demonstration agents, green beans were preserved for the winter by drying. The beans, left whole, were sewn onto threads and dried in the sun for about three weeks. These “leather britches,” shuck beans, or shucky beans were then stored in covered containers for months. Cooking required a long soak in water and about six hours in simmering water on the stove before the proper tenderness was achieved.

Farther south, diners savor butter beans, particularly the speckled variety that William Faulkner supposedly reminisced about in Paris with fellow writer Katherine Anne Porter. Butter beans are related to limas but have a creamier flavor, hence the name. White navy beans, in a thick broth, are common cafeteria fare throughout the South.

Seasoned beans served over rice are basic to the coastal cooking of the South. A traditional Hispanic meal is Moors and Christians, featuring saucy black beans over boiled white rice. In Louisiana, cooking red beans and rice evolved into a Monday tradition, since that was washday and cooks could leave the beans relatively untended on the back of the stove while completing their housework. The dominant seasoning for a pot of red beans and rice is pork, in the form of ham, andouille sausage, or even Spanish-inspired chorizo. Either the stewed, spicy beans are cooked separately and served atop a plate of rice, or the rice is cooked in the bean liquid.

Diners all across the Deep South sit down to bowls of hoppin’ John for good luck on New Year’s Day. This dish is a blend of black-eyed peas and rice, again flavored by pork—ham hocks, side meat, or bacon. Brought to America on slave ships in the 17th century, blackeyed peas are actually beans (Vigna unguiculata) and are also commonly referred to as cowpeas, field peas, or crowder peas. A hip-hop group, the Black Eyed Peas, finds this bean a symbol for their African American–inspired music.

In the novel and play The Member of the Wedding, by Georgia native Carson McCullers, a bowl of hoppin’ John is the final test of a character’s mortality: “Now hopping-john was F. Jasmine’s very favorite food. She had always warned them to wave a plate of rice and peas before her nose when she was in her coffin, to make certain there was no mistake; for if a breath of life was left in her, she would sit up and eat, but if she smelled the hopping-john and did not stir, then they could just nail down the coffin and be certain she was truly dead.”

Beans even show up on the southern dessert table, in the form of bean pies. Pinto beans in the Upper South and red beans in the Deep South are mashed, sugared, and baked in a crust, sometimes with pecans or other nuts added to the filling.

Storehouses of southern soil and sun, beans are nourishing, filling, and inexpensive, giving substance and variety to menus from the mountains to the marshes.

FRED W. SAUCEMAN

East Tennessee State University

John Egerton, Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History (1987); Ronni Lundy, Butter Beans to Blackberries: Recipes from the Southern Garden (1999), Shuck Beans, Stack Cakes, and Honest Fried Chicken: The Heart and Soul of Southern Country Kitchens (1991); Carson McCullers, The Member of the Wedding (1958).

Beaufort Stew/Frogmore Stew

The South Carolina Lowcountry, embracing the Sea Islands and the coastal plain, is home to a broad range of culinary traditions. Greatly influenced by French, English, African American, and Native American foodways, the variety is impressive and includes several seafood stews, of which Beaufort stew, also known as Lowcountry boil or Frogmore stew, is the most well known.

Taking its name from two of the oldest Sea Island communities, Beaufort and Frogmore, the stew typically calls for a rather simple recipe: combine several large boiling potatoes, a couple pounds of smoked sausage, half a dozen ears of corn, and two pounds of shrimp. Most recipes call for these ingredients to be boiled with certain seasonings, like crab boil, and the stew is normally served with hot sauce.

This stew is equally at home on Lowcountry townhouse tables and at the family reunions of people who have traditionally farmed and fished the Sea Islands. This is a clear indication of the sharing of traditions, or creolization, that took place during the era when rice plantations dominated the South Carolina coastal plain. Enslaved African Americans brought from Africa the skills and knowledge needed to grow rice, as well as culinary traditions that became intertwined with traditions of other ethnic groups.

Planters, slaves, and small family farmers all depended on one-pot meals prepared in large black iron kettles. Whether the dish contained potatoes or rice depended largely on availability and time of year. Quoting from the antebellum records of Hagley Plantation, Charles Joyner notes that between April and October each worker was allowed a pint of “small [rice] twice a week” and that “seafood ran a close second in popularity to pork among the Waccamaw slaves,” who added “to their allowances of food by using their off times for fishing, crabbing, oystering, and clamming.”

Even traditional dishes are subject to change and variation, and Beaufort stew is no exception. Although the longstanding prevalence of one-pot meals in American cooking points to antebellum origins, many argue that the nomenclature has been in use only since the middle years of the 20th century. Stories attempting to account for the stew’s origins are numerous. They include tales of a fraternity cookout on a South Carolina beach and the last desperate attempt of an Army National Guard cook to feed the soldiers in his unit. Many scholars attribute the addition of link sausage to the influence of European butchery.

Numerous narratives clearly point to antebellum origins. Sabe Rutledge, who was born on a rice plantation just before the Civil War, told a researcher in the 1930s about two cooking pots maintained by her mother: “Boil all day and all night . . . cedar paddle stir with.” Regardless of differences in nomenclature or recipe variations, one-pot meals have been a significant part of the American cooking heritage for hundreds of years.

The ingredients in Beaufort stew are boiled and then strained. The vegetables, shrimp, and sausage are removed from the pot and eaten only after this straining process is completed. This, when compared to other southern stews, presents a distinct difference in the method of consumption. It is commonly agreed that a Beaufort stew cooked long enough to thicken significantly becomes what folks generally refer to as a muddle.

SADDLER TAYLOR

McKissick Museum, Columbia, South Carolina