Tasso

The word tasso is evidently a Cajun French corruption of the Spanish term tasajo, meaning smoked meat. In the Spanish context, tasajo usually refers to jerked beef, which is used as a flavoring agent in numerous dishes throughout Spain and Latin America. In French Louisiana, on the other hand, tasso specifies highly seasoned jerked and smoked pork. The transformation of the idiom and the food it represents is evidently the result of cross-cultural borrowing and assimilation in rural south Louisiana’s unique melting pot. The origins of the Cajun practice are nevertheless uncertain. Various 18th-century Europeans reported the use of smoked meats by various Native American groups in the lower Mississippi Valley, including the reputedly cannibalistic Attakapas tribe, the indigenous population of south central Louisiana. This existing tradition appears—as the etymology of the food’s name suggests—to have been reinforced by the culinary practices of Hispanic immigrants. In an attempt to Hispanicize the colony’s French population in 1779, Louisiana’s Spanish colonial government settled approximately 60 Malagueños along Bayou Teche at present-day New Iberia. These natives of Malaga, Spain, who subsequently moved to the shores of nearby Spanish Lake, were quickly absorbed into the region’s much larger Cajun community. Although the Malagueños lost their language and identity in the assimilation process, a portion of the community’s culinary tradition evidently lives on in the form of tasso.

The Cajun population engaged in ranching on the upper prairies west of Bayou Teche appears to have embraced the Spanish foodstuff most enthusiastically, perhaps because it provided a means of preserving beef during long cattle drives, which began at approximately the time of the Malagueño influx. Oral history fieldwork in the Cajun parishes suggests that the traditional usage of tasso was confined exclusively to those areas of the Cajun prairies that were most active in transporting cattle to 19th-century New Orleans markets. It is thus fitting that the term tasso first appears in the Louisiana documentary record in 1859 as the name of a prairie community near present-day Duson, in the heart of the early Cajun ranching country. In 1880 nationally famous local-color writer George Washington Cable, who collected notes on the Cajun community for a never-published addendum to the 1880 census report, recorded that “jerked beef (tassao)” and cornbread were the staples of the Cajun diet in the Carencro area, an early ranching center. Over the following century, Cajuns adapted well-established beef jerking techniques to the preservation of pork, which was more widely consumed among Cajun small farmers.

RYAN A. BRASSEAUX

CARL A. BRASSEAUX

Lafayette, Louisiana

Mme. Bégué’s Recipes of Old New Orleans Creole Cookery (1900); Pip Brennan, Jimmy Brennan, and Ted Brennan, Breakfast at Brennan’s and Dinner, Too (1994); Rima and Richard Collin, New Orleans Cookbook (1987); Walter Cowan, Charles L. Dufour, and O. K. LeBlanc, New Orleans: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow (2001); John Egerton, Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History (1987); Peter S. Feibleman, American Cooking: Creole and Acadian (1971); Leon Galatoire, Leon Galatoire’s Cookbook (1995); Lafcadio Hearn, Lafcadio Hearn’s Creole Cook Book (1990); The Picayune Creole Cook Book (1922).

Tea Rooms

Contrary to the sweet-old-lady stereotype, southern-style tea rooms were often bastions of progressive women and precursors of modern fast-food trends. Refused use of meeting halls, southern women’s rights leaders of 1880 met over tea in kitchens, fighting intemperance and lack of schooling for girls. Later, the first female graduates flocked to urban jobs during World War I. Unescorted they were banned from hotel dining rooms and from clubs. Industrious widows answered the need of young women with no place else to eat, calling their homes “tea rooms” and feeding them chicken pie, oyster bisque, and garden vegetable salads.

During Prohibition the tea room craze was at its height. Soups, casseroles, and toasted sandwiches were “fast food” for flappers and their beaus. Afternoon tea dances thrived in hotels from Memphis to Richmond, where “animal dancing” (the Turkey and Fox Trots) scandalized chaperones. Likewise, in Atlanta, the Apache was danced by Margaret Mitchell, Gone with the Wind author.

One enterprising tea room founder displayed her bobbed hair silhouette on a new Atlanta office building. Like other home economics/dietetics graduates, she studied the science of cooking, nutrition, and sanitation. Her light lunches and simple suppers replaced heavy sauces and fussy, five-course dinners favored by European trained chefs. Serving 2,000 patrons per day, “The Frances Virginia,” as her tea room was called, was as busy as a modern McDonald’s.

Tea rooms survived the Depression, showcasing tomato aspic or congealed fruit salad with almonds, made possible by the invention of Jell-O and by refrigerators replacing the icebox. Protestant diehards “revived” with delicate rum cream pies and prune whip with sherry custard sauce.

During World War II, hats flowered. “Tea room cafeterias” trilled with patriotic war brides and “old maid” aunts coming to the city to work, properly attired in gloves and girdles. Department stores advertised “Free Child Care,” helping mothers to “lunch” in peace. Hubs of social and civic activity, they hosted fashion shows, bridal showers, rotary club meetings, employee interviews. Dealing with ration coupons, hot kitchens, and crowded dining rooms, hostesses promoted iced tea, thriftily sweetened while warm, and meatless vegetable luncheons that offered protein through milk or cheese sauce.

Wartime ended. Free nurseries ceased. Hometown tea rooms served Sunday dinner (at noon) with children’s menus. Tea rooms now had furniture made just for juniors and highchairs for baby siblings. Gasoline was no longer rationed, and California iceberg lettuce arrived, plus deviled crab, and pink shrimp cocktails from the Florida coasts. Tea rooms catered to family tradition, serving Thanksgiving turkey, cornbread dressing, and giblet gravy to relatives arriving by train, trolley, and taxi. They packaged tea room takeout turkey, turnip greens, and baked macaroni in cylindrical, cardboard containers for those who dined at home. Though the food was similar, the decor differed from that found in dark “grills” and smoky “restaurants,” subtly suggesting “Men Only.” Though segregated, tea rooms in black and white neighborhoods followed similar trends. Tea rooms began to decline in the 1950s. Owners and patrons aged. Chicken à la king could not compete with Elvis and pizza.

MILLIE COLEMAN

Atlanta, Georgia

Mildred Coleman, The South’s Legendary Frances Virginia Tea Room Cookbook (1996); Pamela Goyan Kittler and Kathryn Sucher, Food and Culture in America (1989); Jan Whitaker, Tea at the Blue Lantern Inn: A Social History of the Tea Room Craze in America (2002).

Tomatoes

Many southerners have fond memories of going to the tobacco patch to harvest tobacco and to eat tomatoes growing in rows adjacent to the tobacco rows. The warm tomatoes, cut open with a pocketknife or simply pried open with the thumbs of both hands and liberally sprinkled with salt from a shaker carried in pants pockets, were (and are) a taste treat to be savored and remembered. Many also remember canning tomatoes, making tomato juice during brief times of surplus, and taking tomato sandwiches to school or to work, either on biscuits or loaf (white) bread smothered with mayonnaise.

Brought from South America, the tomato burst onto the southern landscape before traveling northward. Tomatoes came to America surrounded by a particular mythology that warned that they were a form of poisonous apple. In the early South, many gardeners and consumers remained suspicious of the tomato because of this legend. The tomato continued to entertain a controversial history in America, and even in the South, after such myths faded. S. D. Wilcox, editor of the Florida Agriculturalist reported that he ate his first tomatoes in 1836, as part of an experiment, in a pie without any seasoning or sweetening. He summed up his consequent dislike for the tomato: “[The tomato] is an arrogant humbug and deserves forthwith to be consigned to the tomb of all the Capulets. . . . [Anyone] who would have predicted that the tomato would ever become popular as an esculent or to be used in any utilitarian way except as gratification to the eye, would have been set down at once as daft or visionary.”

Despite its early bad press, the tomato has long been a staple of southern family gardening and, in many southern states, commercial gardening as well. Prior to the development of commercial hybrids, most families saved their own tomato seeds or got them, by purchase or by trade, from neighbors. Such tomatoes are of many sizes, colors, shapes, and flavors. Among them are the well-known reds, of course, but also the Cherokee Purple, which came from the Cherokee Indians, and the German yellows (yellow with red stripes), which came from the Amish and Mennonites. Other older tomatoes include the multiple-origin oxhearts, with their heartlike shape (though no two are shaped quite the same); the Mortgage Lifter, which was developed through cross-breeding by a radiator repairman in West Virginia; and a host of varieties of ranging in color from white to black to those that remain green even when ripe. Many families also have their own variety of cherry tomato (tommy-toes), which may have been in the family for generations.

The South also has its own tomato breeding tradition most recently enhanced by the work of Randy Gardner of North Carolina State University. In his work at the Fletcher Experiment Station near Asheville, N.C., since 1976 Gardner has developed the “Mountain Series” of tomatoes widely sought after by commercial growers and by home gardeners as well. Through the use of traditional breeding techniques, Gardner has developed many varieties of disease-resistant tomatoes, most with excellent flavor. Originally from Hills-ville, Va., Gardner experienced the problems of early and late blight as a farm youth and decided in graduate school to devote his career to trying to solve some of the most vexing problems facing both home gardeners and commercial growers. His varieties continue to be in high demand, and he is in demand as a speaker to commercial growers and home gardeners alike.

While hybrids have taken over much of the commercial trade in tomatoes, the reemergence of farmers’ markets, throughout the South and the rest of the nation as well, has given new prestige to (and generated new demand for) oldfashioned or heirloom varieties. Customers can buy freshly picked heirloom varieties and not have to worry about shelf life since the tomatoes will be eaten soon after purchase and certainly only a day or two after being picked. Farmers’ markets have popularized shapes and colors of tomatoes unknown to many of today’s consumers but common to their great-grandparents. Yellow tomatoes, with their high sugar content, and pink tomatoes, with their many blends of sugars and acids, are becoming increasingly popular, both with home gardeners and with market gardeners and their customers.

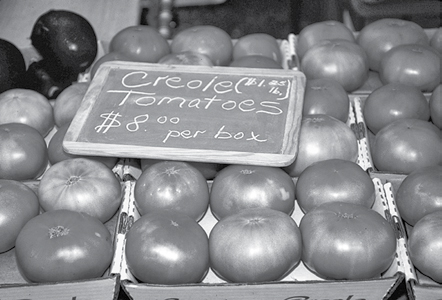

Creole tomatoes for sale at market (Bill Tarpenning, photographer, United States Department of Agriculture)

While tomatoes are increasingly popular in the United States and throughout most of the world, they have a special place in the lives of southerners, who grow many different types and who sometimes serve them three at meals a day during the summer—not to mention the tomato sandwiches enjoyed between meals. The tomato enjoys references across southern musical traditions, from blues artist Brownie McGhee’s “Picking My Tomatoes” (1940) to southern folksinger Kate Campbell’s “Jesus and Tomatoes” (2004), which tells the comic story of a woman who sees the likeness of Jesus in one of her homegrown garden tomatoes. Southern writers also recognize the important place of the tomato in southern culture. In her book Truelove and Homegrown Tomatoes (2003), author Julie Cannon constructs the seasonal life of a tomato patch as the central metaphor for joy and tragedy that mark the life of a family in Euharlee, Ga.

Along with the fresh tomato served cold, southerners also claim two methods of preparing hot tomatoes: stewed tomatoes and fried tomatoes. Fried green tomatoes, a popular breakfast and lunch side dish, have distinctive southern origins. Through the work of Fannie Flagg’s 1987 novel Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Café and the movie based on it, Fried Green Tomatoes (1994), this dish has become synonymous with southern culture and southern cooking. In the novel, the sharing of a plate of fried green tomatoes symbolically connects Evelyn Couch, a lonely middle-aged woman, with the childhood community, sisterhood, and secrets of her elderly friend, Ninny Threadgoode.

BILL BEST

Berea, Kentucky

FRANCES ABBOTT

University of Mississippi

Lee Bailey, Tomatoes (1992); John Egerton, Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History (1987); Ronni Lundy, Butter Beans to Blackberries: Recipes from the Southern Garden (1999); Andrew F. Smith, The Tomato in America: Early History, Culture, and Cookery (1994).

Uncle Ben’s

Uncle Ben’s is one of the world’s most successful brands of commercially prepared rice, thanks in large part to the marketing skills and dedication of the company’s founder, Gordon Harwell. Harwell, a produce broker in Houston, saw an opportunity to fundamentally change the commercial rice market in the United States. Prior to the 1930s, short-grain rice was locally grown, milled, and sold. For the consumer, such rice often varied in quality. Harwell believed that if he could market rice as a premium food rather than a commodity, he would be successful. Harwell bought rice grown in the Houston area and packaged it under the trade name Uncle Ben’s, hoping that the African American symbol would “connote old fashioned goodness” to the customer. Unfortunately, the product still varied in quality, and Harwell needed a way to produce rice of a consistent appearance, quality, and taste.

The solution came in a new “conversion” process that was invented by Eric Huzenlaub, a chemist who emigrated from Germany to England in the 1930s. Under the conversion process, brown, long-grain rice is parboiled under steamed pressure to force water-soluble nutrients into the starchy endosperm and then dried and milled. After the process, the “converted rice” has more nutrients, less oil, and a harder texture than short-grain rice, and a white appearance that is similar to that of shortgrain rice.

Harwell contacted Huzenlaub about licensing the conversion process, but Huzenlaub was not initially interested because he considered the United States too small as a rice market, especially compared to a country such as India. Eventually, Harwell persuaded Huzenlaub to grant him a license, and his converted-rice company was ready to launch. The United States military became the first large customer to try the product, then marketed as “Ehler’s Converted Rice.” The converted rice was easy to store, resistant to weevil infestation, and thus perfect to feed hungry soldiers in the South Pacific theater of World War II. By 1945, Ehler’s Converted Rice was shipping 65 million pounds of its product to the military.

As World War II was coming to an end, Harwell understood that the military purchase orders were drying up and that he had to develop a consumer market for converted rice. He decided to focus the company’s marketing efforts in the New York City area, believing that if they could make it there, they would make it everywhere. Harwell resurrected the “Uncle Ben’s” brand he had used in the Houston area a decade before. The company advertised heavily in local media like the New York Times, and Harwell even hosted an all-rice-dish dinner for several New York food executives and restaurateurs. Harwell’s focused sales campaign worked wonders, for soon “Uncle Ben’s Converted Rice” became a household name in kitchens across the country.

Early advertisements for Uncle Ben’s rice often emphasized the qualities of rice prepared in the “southern” or “South Carolina” method. In sharp contrast to the gummy mess that usually resulted when short-grain rice was cooked, converted rice, when cooked, still looked white, and it separated easily so that “every grain salutes you.”

Although the company’s website describes Uncle Ben as a legendary Texas rice farmer, there is not much information available about him. In some early press interviews, Harwell said that he wanted a persona who would connote the beginning of rice growing in the American South. He thought of the apocryphal blacks of the South Carolina plantations who had so much to do with early rice growing. For the company logo, Harwell ultimately settled on a likeness of Frank C. Brown, an African American man who waited on, and impressed, him during a dinner in a Chicago restaurant.

We may never be able to separate myth from reality, but Uncle Ben’s rice does hearken back to the forgotten days of African American achievement in rice growing and cookery. Throughout the slave trade, West African rice farmers were enslaved and targeted for sale to slaveowners in South Carolina, Georgia, and Louisiana who wanted to exploit their specialized knowledge and skills with rice. These enslaved Africans used rice to create some signature dishes of Lowcountry cuisine, like hoppin’ John, pilau, and rice bread. Though the African American cook’s reputation with rice was certainly forged in the South, it clearly made its way to the North. For example, The Pentucket Housewife, an 1888 cookbook published in Haverhill, Mass., featured a recipe, simply titled “A Black Man’s Recipe to Dress Rice.”

ADRIAN MILLER

Denver, Colorado

George Kent, Washington Post (16 January 1944); Marilyn Kern-Foxworth, Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben, and Rastus: Blacks in Advertising, Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow (1994); James J. Nagle, New York Times (24 May 1953).

Waffle House

When Bob Dole ran for president in 1996, he quipped that Bill Clinton was so shifty he had turned the White House into the Waffle House. With that pun, one of the most familiar sights of the southern roadscape fully arrived in the national consciousness. From its greasy beginnings as a short-order joint in Georgia, Waffle House has spread to more than 1,500 locations in 20-plus states. A smattering of the chain’s yellow waffle iron signs appears in the Midwest and the Rocky Mountain states, but the great majority are in the Deep South, where the always-open restaurants have inspired something of a cult following among police officers, truck drivers, night owls, and overcaffeinated college students.

The first Waffle House opened on Labor Day 1955 in the Atlanta suburb of Avondale Estates. One of the founders, Joe Rogers Sr., had worked for a similar restaurant chain in Memphis, Toddle House, but quit because he could not get an ownership stake. Half a century later, Waffle House remains privately owned and based near Atlanta.

Unlike most franchise operations, Waffle Houses have a charmingly retro intimacy about them. The shoeboxshaped units are small, with a few hard plastic booths and counter stools facing an open kitchen where all the cooking is done in full view on toasters, irons, and a griddle top. The menu is basic: eggs, waffles, burgers, grits, hash browns. Waitresses seem to know all the regulars by name and call other customers “hon” or “darlin’.” Orders do not appear on a computer screen; servers stand at the end of a counter and bark them out in vintage diner slang.

To complete the truck stop atmosphere, every Waffle House has a jukebox stocked with corny, countrified tunes about eating at Waffle House. Among the titles are “Waffle Do Wop,” “There Are Raisins in My Toast,” and “844,739 Ways to Eat a Hamburger” (a Georgia Tech mathematics class actually calculated the permutations). Many customers know that some of the songs were recorded by Mary Rogers, the wife of the chief executive—another homey touch that no doubt enhances their feeling that when they eat at the Waffle House, they are among family.

JIM AUCHMUTEY

Atlanta Journal-Constitution

John T. Edge, Southern Belly: The Ultimate Food Lover’s Companion to the South (2000); Bill Osinski, Atlanta Journal-Constitution (24 December 2004); Richard Pillsbury, From Boarding House to Bistro: The American Restaurant Then and Now (1990); Waffle House website: www.wafflehouse.com; Kristen Wyatt, “Still Dishing at Age 50,” Associated Press (13 August 2005).

Walter, Eugene Ferdinand

(1921–1998) CULINARY ENTHUSIAST, WRITER.

A native of Mobile, Ala., Eugene Ferdinand Walter was a man of catholic tastes and insatiable intellectual curiosity. At various points in his career, he worked as a novelist, poet, essayist, artist, lyricist, actor, designer, translator, humorist, botanist, marionetteer, philosopher, and cookery writer. He was a founding contributor of the Paris Review and a contributor to a multitude of magazines and journals, including Harper’s, Botteghe Oscure, and the Transatlantic Review. He published numerous chapbooks of poetry; collections of short stories, including The Byzantine Riddle (1985); and a prizewinning novel, The Untidy Pilgrim (1954).

Perhaps his most engaging work was in the broad field of culinary letters. His food writing was intelligent, worldly, and playful, worthy of comparison to the best of M. F. K. Fisher. Throughout his life, Walter espoused the virtues of good food and drink. Of Mobile natives he observed, “It’s a toss-up whether they rank the pleasures of the table or the pleasures of the bed first, but it’s a concrete certainty that talk follows close after.”

Walter was a lifelong student of Mobile, a sort of unofficial curator of its quirky charms. In The Untidy Pilgrim, he introduced the world to his hometown. “Down in Mobile they’re all crazy,” he wrote, “because the Gulf Coast is the kingdom of monkeys, the land of clowns, ghosts and musicians, and Mobile is sweet lunacy’s county seat.”

Walter was not provincial. While on prolonged sojourn in Rome, during the 1950s and 1960s, he ate and drank with a group of friends that included Federico Fellini. He worked as a translator and actor in several Fellini films, including 8½ (1963), and wrote the lyrics for the song “What Is a Youth?” for Franco Zeffirelli’s film of Romeo and Juliet. And yet, no matter where he might live, a love of southern food and frolic remained at the core of his being. “In Rome I live as I lived in Mobile,” he wrote. “On my terrace garden I have five kinds of mint, five kinds of onions and chives, as well as four-o’clocks and sweet olive. I take a nap after the midday meal; there is always time for gossip and for writing letters.”

Walter’s dedication to the southern culinary arts brought him back home in 1969 to write American Cooking: Southern Style, among the best of the Time-Life Foods of the World series. In succeeding years, he wrote about culinary matters in Gourmet and numerous other publications. During his later years, Walter published two overlooked jewels: Delectable Dishes from Termite Hall: Rare and Unusual Recipes (1982) and Hints and Pinches: A Concise Compendium of Herbs and Aromatics with Illustrative Recipes and Asides on Relishes, Chutneys, and Other Such Concerns (1991).

The latter, suffused with Walter’s fanciful pen-and-ink drawings of mango-eating monkeys, dancing cats, and crown-bedecked bulbs of garlic, is a funhouse encyclopedia of the culinary arts. (An illustration therein depicts a lady of aristocratic bearing, attired in a purple-and-gold-striped skirt, her hand resting on an oversized fork as if it were a scepter. The caption reads: “The Devil’s dear Grandmother pondering what menu to serve when she invites Pat Robertson, Jerry Falwell and Jesse Helms to dine in Hell with Hitler and Mussolini.”)

At turns erudite and irreverent, Hints and Pinches is not an easy book to encapsulate. It is a work of folklore: “Medieval magicians put celery seeds in their shoes,” writes Walter, “believing this could make it possible for them to fly.” It is a showcase for the author’s prejudices: “Powdered cloves, like the dead dust sold as [ground, black] pepper, is as far from the flavor of a freshly ground clove as Helsinki is from Las Vegas.” And it contains a surfeit of recipes, among them instructions for the proper preparation of persimmon jam, beet-tinted “Southern Belle” ice cream, chayote rellenos, nasturtiuminfused vinegar, and baked bass flavored with yogurt, walnuts, and pomegranate seeds.

Eugene Walter died on 29 March 1998. He was interred at Mobile’s historic Church Street Graveyard on 2 April after a spirited wake, during which, at Walter’s instruction, celebrants feasted on “chicken salad sandwiches, port wine, and plenty of nuts.” In the wake of his death, southerners have begun to rediscover Walter’s culinary legacy by way of admirers like novelist Pat Conroy.

JOHN T. EDGE

University of Mississippi

Rebecca Barrett and Carolyn Haines, eds., Moments with Eugene (2000); Catherine Clarke, Milking the Moon (2001); Pat Conroy, The Pat Conroy Cookbook (2004).

Washington, George

(1732–1799) U.S. PRESIDENT, AGRICULTURALIST.

A third-generation Virginian who became a prominent military hero and statesman, George Washington brought hundreds of visitors to his home, Mount Vernon, each year and had the opportunity to extend hospitality to people ranging from neighbors on nearby plantations to a delegation from the Catawba nation and members of the noble houses of Europe. Some idea of the number of visitors welcomed to the estate can be found in Washington’s diaries. For example, in the 16 years between their marriage and the Revolution, George and Martha Washington entertained at least 418 individuals at their home. Following the war, between 1784 and 1789, they accommodated at least 588 individuals at Mount Vernon. The figures remained high following Washington’s retirement from the presidency. In 1798, for example, there were guests for dinner on 203 of the 310 days for which records exist. In terms of total numbers, in that year, the Washingtons had at least 656 guests for dinner. By the end of his life, the volume of traffic through his home sometimes led Washington, who once compared Mount Vernon to “a well-resorted tavern,” to look back with longing to the days before he had become a household word. In a letter to a friend, he described a typical dinner, “at which I rarely miss seeing strange faces; come, as they say, out of respect to me. Pray, would not the word curiosity answer as well?” He went on wistfully, “and how different this, from having a few social friends at a cheerful board?”

Three to four meals were typically served each day at Mount Vernon. Because both George and Martha Washington rose before sunrise, breakfast was on the table at seven o’clock in the morning, about one to two hours earlier than on other Virginia plantations of the period. Despite the variety of meats, fish, breads, and beverages (tea, coffee, and chocolate) from which to choose, Washington invariably had hoecakes (cornmeal pancakes) “swimming in butter and honey,” which he washed down with hot tea. The main meal of the day was the midafternoon dinner, served in three courses. The first course offered diners a large selection of meats and vegetables, while the second course included a like number of desserts and preserved fruits. Where Washington was partial to fish at this meal, his wife had a fondness for other types of seafood. The meal ended with a course of fresh fruits, nuts, and sweet wines, of which Washington is said to have particularly enjoyed walnuts and Madeira. Later in the day, about six or seven o’clock in the evening, the family had tea, a light meal consisting of bread, butter, perhaps some cold meat or cheese, cake, and the beverage that gave this repast its name. The Washingtons generally went to bed at about nine o’clock, so supper, another light meal served about that time in many households, was not usually offered, unless there were special guests with whom the general wanted to stay up to talk.

Washington once wrote to an old friend, “My manner of living is plain . . . a glass of wine and a bit of mutton are always ready, and such as will be content to partake of them are welcome, those who expect more will be disappointed.” This was a bit of an understatement, for the tables at Mount Vernon were loaded with foodstuffs, both those grown and prepared on the plantation (beef, pork, mutton, dairy products, and a wide variety of fruits, nuts, and vegetables) and imported from around the world (spices, wines, cheeses, olives, nuts, tea, coffee, sugar, molasses). As mistress of the plantation, Martha Washington oversaw the kitchen, the garden that supplied the table, the poultry yard, the dairy, and the smokehouse. She also discussed menus with the enslaved cooks on a daily basis. For inspiration in this task, she might have turned to either the manuscript cookbook she inherited from the family of her first husband, Daniel Parke Custis, or to her copy of the most popular English cookbook available in America at the time, The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy, by Hannah Glasse.

MARY V. THOMPSON

Mount Vernon Ladies’ Association

W. W. Abbot, Dorothy Twohig, Philander D. Chase, et al., eds., The Papers of George Washington, Colonial Series, Revolutionary War Series, Confederation Series, Presidential Series, and Retirement Series, 46 vols. to date (1983–); George Washington Parke Custis, Recollections and Private Memoirs of Washington, By His Adopted Son (1860); Susan Gray Detweiler, George Washington’s Chinaware (1982); Joseph C. Fields, ed., “Worthy Partner”: The Papers of Martha Washington (1994); John C. Fitzpatrick, ed., The Writings of George Washington from the Original Manuscript Sources, 1745–1799, 39 vols. (1931–44); Karen Hess, ed., Martha Washington’s Booke of Cookery (1981); Donald Jackson and Dorothy Twohig, eds., The Diaries of George Washington, 6 vols. (1976–79).

Watermelon

Watermelon is among the best examples of the mythic significance of food in southern culture. The eating of watermelon is one of the most symbolic rituals of southerners. To be sure, watermelon is not a unique possession of the American South. Watermelon seeds have been discovered in Egyptian tombs from thousands of years ago, and Mediterranean peoples have cultivated the plant for centuries. Northern Americans eat watermelon, although their climate enables them to raise only small-fruited and midget varieties.

An annual called Citrullus lanatus, southern watermelon is a member of the gourd family. It grows during the South’s warm, humid summers, requiring a 120-day growing season. Southern watermelons are called “rampantgrowing varieties,” and they have regionally meaningful names such as the Dixie Queen, Dixielee, Stone Mountain, Charleston Gray, Alabama Giant, Florida Giant, Louisiana Queen, Carolina Cross, and Africa 8. Africans introduced watermelon to Europe and later North America, and Indians in Florida were cultivating it by the mid-17th century. Thomas Jefferson grew watermelons at Monticello, but they were found among the crops of yeoman farmers more often than those of planters. Garden patches that fed many an impoverished southerner in the postbellum South often included watermelons. They were a low-cost treat even during the Depression, and some southerners still call the watermelon a “Depression ham.”

Watermelon has been especially associated in the United States with rural southern blacks. It became a prop identified with the stereotypical Sambo—the childlike, docile, laughing black boy was seen grinning and eating watermelon. This derogatory image was pervasive in popular literature and art, and watermelon-eating scenes later became stock features of films and newsreels. Watermelon has been, nonetheless, a cultural symbol used also in less negative ways as well by southerners and others. Folklore has long told of the proper ways to plant watermelon (by poking a hole in the ground and planting the seed by hand), and the ability to tell a ripe watermelon by thumping it was a legendary rural skill. Literature tells of the simple joys of eating watermelon. Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn (in Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer, Detective: As Told by Huck Finn) “snuck off” from Aunt Sally one night and “talked and smoked and stuffed watermelon as much as two hours.”

The Skillet Lickers chose a traditional southern folk tune, “Watermelon on the Vine,” for one of the earliest recordings of southern country music, and Tom T. Hall celebrated the melon in the more recent “Old Dogs, Children, and Watermelon Wine.” The lyrics to the blues song “Watermelon Man” identified the succulent melon with sexual potency, and a 1970 Melvin Van Peebles film about the experiences of a white man who wakes up one morning with a black skin was also called Watermelon Man. The watermelon has been used as an advertising symbol, especially on roadsides to direct motorists to stands selling the delicacy. Miles Carpenter, of Waverly, Va., began carving wooden watermelon slices and painting them with enamel decades ago, and today he is recognized as an accomplished folk artist.

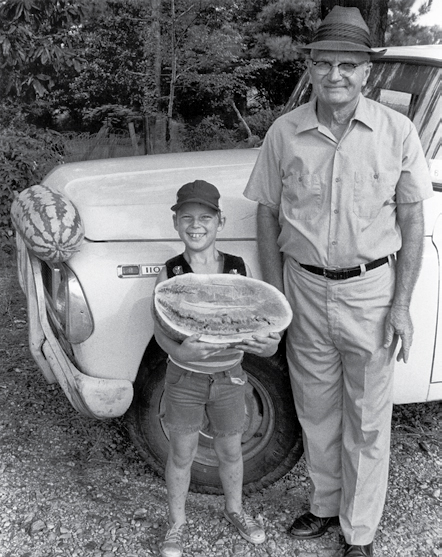

Watermelon vendors, Warren County, Miss., 1975 (William R. Ferris Collection, Southern Folklife Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

In the contemporary South the watermelon remains a part of the summer diet. Cookbooks have recipes not only for the traditional chilled melon, melon balls, pickled watermelon rind, and spiked melon, but also for watermelon and cassis ice, spiced watermelon pie, and watermelon muffins. But the importance of watermelon to southerners transcends its use as food. When popular periodicals discuss symbols of the region, they usually include watermelon (Southern Magazine, June 1987; Texas Monthly, January 1977). Summer recreation includes festivals, and watermelon is the central feature of festivals at Luling, Tex.; Hampton County, S.C.; Chiefland, Chipley, Lakeland, and Monticello, Fla.; Grand Bay, Ala.; Raleigh, N.C.; and Mize and Water Valley, Miss. The U.S. Watermelon Seed-Spitting Contest is held during the National Watermelon Association’s annual convention in Moreven, Ga., the first week of March. Hope, Ark., may be the watermelon capital of the South. The town advertises itself with a logo that has a picture of a watermelon and the claim that Hope offers “a slice of the good life.” Hope farmers regularly raise 100–150 pound watermelons. Another southern town, Cordele, Ga., claims the motto “The Watermelon Capital of the World” and is home to the Watermelon Capital Speedway. Every year, Cordele hosts the Watermelon Days Festival, which includes mass consumption of locally grown watermelons, arts and crafts, a parade, and seed-spitting competitions.

Southerners would likely still agree with a passage in Mark Twain’s Pudd’nhead Wilson: “The true southern watermelon is a boon apart and not to be mentioned with commoner things. It is chief of this world’s luxuries, king by the Grace of God over all the fruits of the earth. When one has tasted it, he knows what the angels eat. It was not a southern watermelon that Eve took; we know it because she repented.”

CHARLES REAGAN WILSON

University of Mississippi

Ellen Ficklen, Watermelon (1984); Daniel Wallace, The Watermelon King (2003); William Woys Weaver, Gourmet (July 2004); John Edgar Wideman, Damballah (1998); David Scofield Wilson and Angus Kress Gillespie, eds., Rooted in America: Foodlore of Popular Fruits and Vegetables (1999).

Wilson, Justin

(1914–2001) CAJUN CHEF AND HUMORIST.

Born at Roseland, La., on 24 April 1914, Justin Wilson was the son of Harry D. Wilson, the Pelican State’s commissioner of agriculture from 1916 to 1948, and Olivett Toadvin. One of six children, Wilson was reared in his native Tangipahoa Parish, part of the state’s Anglo-American Bible Belt, before attending Louisiana State University at Baton Rouge. When Wilson left the university without a degree after “majoring in girls,” he became an itinerant day laborer until two events changed his life. In 1935 he met Will Rogers, who inspired Wilson to pursue a career in public speaking. In addition, during the early 1930s, Wilson obtained a patronage job “policing the state’s grain warehouse industry.” His duties as a safety engineer occasionally took him into southwest Louisiana’s predominately Cajun rice-producing region. During these travels, the engineer began to hone his skills as a comedic storyteller, basing his humorous tales on the Cajun community.

As he developed his stage persona, Wilson modeled his style on that of the state’s leading contemporary storyteller/entertainer, Walter Coquille, whose Mayor of Bayou Pom-Pom radio show was perhaps the region’s most popular Great Depression era program. New Orleanian Coquille masqueraded as Cajun Télésfore Boudreaux, mayor of the fictional Bayou Pom-Pom community.

Following Coquille’s death in 1957, several emerging entertainers moved to fill the void, including Justin Wilson, who began making appearances on the regional convention and banquet circuit. Like Coquille’s Boudreaux, Wilson’s act combined elements of the same southern minstrel and storytelling traditions that produced Rod Brasfield, Minnie Pearl, and the popular Hee Haw comedy revue. The middle-class jokester poked fun at south Louisiana’s Francophone working class by using fractured, Cajun-inflected English and malapropisms as bases for humorous stories. In the 1960s Wilson, who claimed to have learned to cook at the age of eight as a means of avoiding field work, launched another career as a cookbook writer. He released his first publication in 1965, a privately printed work simply entitled Justin Wilson Cook Book. In 1968 Wilson’s career as a comedian and writer profited immensely from the burgeoning Cajun cultural renaissance, as he gained national and, later, international notoriety.

In the 1970s Wilson capitalized upon the mounting popular interest in the culture by launching a popular Cajun cooking show eventually syndicated on PBS. The show’s success, in turn, contributed to the appeal of Wilson’s comedy albums and cookbooks. The Library of Congress catalog lists eleven publications by Justin Wilson, all but two of which are cookbooks. Four of these publications appeared during the initial surge of national interest in Cajun culture (1974–79), while three works appeared in each of the two ensuing decades. The Library of Congress catalog also indicates that Wilson released 12 comedy albums in the 1970s and 17 commercial recordings in the 1980s.

“How y’all are?” Justin Wilson, a Louisiana legend (Courtesy Justin Wilson Holding Company)

In the 1990s Wilson stopped releasing albums and devoted his attention to his syndicated cooking program. Fans of the cooking show, comedy albums, and cookbooks were charmed by the comedian’s “quaint” language. On the other hand, some Cajuns, particularly academicians and cultural activists, took a very dim view of Wilson, regarding him as an offensive impersonator in the tradition of the 19th- and early 20th-century “ethnic comedians,” who lampooned the nation’s ethnic and racial minorities. Wilson countered his critics with the claim that he was part Cajun through his maternal line. That claim, however, is spurious. Olivett Toadvin was of French immigrant ancestry, not of Acadian/Cajun descent—a fact confirmed by a close family member in a recent interview. Nor was she French-speaking, according to the 1910 census of Louisiana.

It is thus ironic that Justin Wilson, the faux Cajun cultural icon, should reach the pinnacle of his success during the era of political correctness. Wilson, who spent his declining years in Summit, Miss., died on 5 September 2001 and was subsequently interred at St. William’s Cemetery in Port Vincent, La. Wilson, who was married several times, was survived by three daughters.

CARL A. BRASSEAUX

RYAN A. BRASSEAUX

Lafayette, Louisiana

Justin Wilson, Justin Wilson’s Cajun Fables (1982), Justin Wilson’s Cajun Humor (1979), Justin Wilson’s Classic Louisiana Cookin’ (1993), Justin Wilson Cook Book (1973), Justin Wilson’s Easy Cooking: 150 Rib-Tickling Recipes for Good Eating (1998), The Justin Wilson Gourmet and Gourmand Cookbook (1984), Justin Wilson’s Homegrown Louisiana Cookin’ (1990), Justin Wilson Looking Back: A Cajun Cookbook (1996), Justin Wilson Number Two Cookbook: Cookin’ Cajun (1980), Justin Wilson’s Outdoor Cooking with Inside Help (1986), More Cajun Humor (1984).

Wine

The South may be better known for bourbon and moonshine than for wine, but wine has always had a place in the social culture of the region—before 1776 and since. Imported wine was an accepted and popular social beverage among the elite of the colonial and antebellum South, particularly in port cities such as Baltimore, Richmond, Charleston, Savannah, Mobile, and New Orleans.

In many of the wealthier homes it was not uncommon to keep a decanter of port, sherry, or Madeira on the sideboard of the dining room or parlor. In the 1850s, wine clubs in Charleston and Savannah regularly hosted what were among the country’s first wine tastings. Although moonshine and corn liquor were the beverages of choice for strong drink throughout the South, particularly in the rural highlands of the Appalachians and Ozarks, wine was also consumed, made from fruits and berries, wild or cultivated, and from herbs for medicinal and tonic uses.

America’s culinary revolution in the last decades of the 20th century and the concomitant surge of interest in table wine (made solely from grapes) was a little slower coming to the South, but today it is firmly entrenched and still growing. Restaurants with top-flight wine lists of American and imported wines exist in all major cities of the South and even smaller cities and towns, be it Tampa, Fla., Raleigh, N.C., or Cleveland, Miss. Privately owned wine collections of international renown can be found in Nashville, Memphis, New Orleans, Houston, and Dallas, the environs of Washington, D.C., and Miami. Nashville’s annual charity wine auction, l’Eté de Vin, is one of the largest and most lucrative in the United States.

The South is making history, however, with its own wine industry, which has flourished dramatically in the last 20 years. Southern wines—viognier and merlot from Virginia, cabernet and syrah from Texas, cabernet franc from Georgia, for instance—frequently garner awards in national wine competitions. Wines from Texas, Virginia, and North Carolina are available in several major metropolitan areas, including Los Angeles, New York, Washington, and Chicago; some are now exported to Europe, Scandinavia, and the Far East.

Surprising as it may seem, America’s very first wines were likely made in the South. French Huguenots who had settled near what is now Jacksonville, Fla., in the 1560s produced wine from native grapes, probably the same wild varieties of muscadine spotted along the East Coast by Viking voyagers a thousand years ago. Some 500 years after the fabled Norse sightings, Sir Walter Raleigh made an early stab at making wine from the scuppernong grapes he found growing near the Carolina coast. His shipmasters noted the exotic scent of wild scuppernong (Vitis rotundifolia) along the shore: “The smell of sweetness filled the air as if they were in the midst of some delicate garden.”

The Jamestown settlers of 1607 cultivated vineyards, though it is not known whether they actually made wine. Many of the early colonists imported European vine cuttings and encouraged wine growing, from Lord Delaware to Lord Baltimore to Governor James Oglethorpe in Georgia. None, however, was successful, just as Thomas Jefferson’s efforts with European varieties failed—and for the same reasons. Jefferson believed that America, and particularly Virginia, had great potential for wine growing; he viewed wine as a more temperate beverage, an antidote “for the bane of whiskey,” whose abuses ultimately led to Prohibition. Jefferson’s dream for producing classic wines such as those he tasted in Europe and imported for his own wine cellar never materialized, despite efforts at Monticello with varieties such as cabernet sauvignon, merlot, Sangiovese, and Riesling. The European vines (Vitis vinifera) succumbed to various assaults—January thaws followed by sudden freezes that killed the buds, mildew in the humidity of summer, or soil-borne pests that devoured the tender vine roots—problems finally solved only in the latter part of the 20th century. Jefferson would undoubtedly be pleased at Virginia’s success with vinifera grapes today as the South’s largest producer of vinifera wines.

Thomas Jefferson’s passionate pursuit of wine growing at Monticello failed, but his interest in wine had significant impact on wine traditions in the young republic. During his five-year tenure in France as U.S. ambassador during the Washington administration, he acquainted himself with the best wines of that country, traveling extensively in the great vineyards of Burgundy, the Rhône Valley, and Bordeaux, as well as visiting wine regions in Italy and Germany. His personal records show numerous orders for shipments of fine wine to John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, James Madison, and George Washington, including one order of 40 cases of champagne for the president. Jefferson and Washington both prized good Madeira, maintained sizeable stocks of it, and were known to enjoy a glass of it almost daily.

Jefferson, recognizing the difficulty of adapting European vines to New World conditions, encouraged American grape breeders working with domestic grapes, including John Adlum of Maryland, who developed the Catawba grape; Samuel Maverick of South Carolina; and Dr. Daniel Norton of Virginia, who hybridized the Virginia seedling, or Norton grape, in the early 1800s. Later in the century, a Virginia red wine made from Norton took silver medals at the Paris Exposition of 1878. Today this same grape variety has produced several prize-winning wines from Virginia, Missouri, and Georgia.

By the 1870s several southern states had thriving wine industries, notably North Carolina and Virginia, but also Georgia, which, according to an 1880 Department of Agriculture report, was the sixth largest wine producer in the United States. In these states the native scuppernong and muscadine varieties produced huge quantities of wine shipped all over the country. Arkansas and Texas also produced quantities of wine from native grapes. It was, in fact, tough native rootstock grown in Texas and the Ozark highlands that saved the vineyards of Europe in the late 1880s when they were ravaged by a root pest, Phylloxera.

With temperance in full swing by the early 20th century, several southern states voted to go dry, and Prohibition virtually destroyed wine production throughout the United States. Even after repeal in 1933, however, Prohibition maintained a stranglehold in the South, particularly in the Bible Belt, where some counties remain dry today. A significant breakthrough for winegrowers in all of the southern states came when they finally gained support from state legislatures for farm winery bills enabling them to produce and sell wine. Still, in one of those curiously southern quirks of religion and politics, there are a few counties that permit winery operation and the making of wine but prohibit sales of any alcoholic beverage.

The revolution in southern wines took its first leaps in the mid-1970s, when a handful of winegrowers in Virginia and Texas bucked scientific advice and planted the European wine varieties—Vitis vinifera—that supposedly could not grow east of the Rockies, and especially not in the South. These pioneers found it a struggle at first, trying to discover the keys to success in untried regions. Within a decade or so, however, improved viticultural techniques and better wine making began to pay off in wines of quality and style. The global success of California wine during the 1980s accelerated interest in and demand for good table wine in all parts of the United States. Momentum came also from America’s gastronomic awakening, with its new awareness of regional specialties and homegrown food products.

As southern winegrowers began to understand the best spots for growing desirable grapes, as they gained experience in making stylish wines of better quality, they were able to capitalize on the flourishing interest in wine and attract local followings. By the mid-1990s wineries in several southern states were enjoying excellent success—and attracting attention nationwide.

The South’s best wines come from a few states, notably Virginia, Texas, North Carolina, and Georgia, but quality wines increasingly pop up in Maryland, Arkansas, Tennessee, even Florida and Louisiana. Vineyard acreage is increasing in many areas, especially in the upland regions of the Upper South and in the mid-Atlantic states, where grape growing is considered a viable option to tobacco cultivation.

Many wineries still find it useful commercially to produce wines from French and American hybrids such as Seyval blanc, Vidal, Chambourcin, Catawba, and Cayuga, more prolific varieties that help with cash flow and ripen more reliably than vinifera. Improved quality and drinkability of these wines has gained greater acceptance, particularly important for regions where growing vinifera grapes is marginal or impossible, such as tropical and subtropical regions of the Deep South and Florida. Wineries in Florida, for instance, have benefited enormously from collaborative work with grape scientists at Florida State University developing new muscadine hybrids that produce sound dry and off-dry table wines.

Most wine consumers, in the South as elsewhere, prefer wines made from vinifera grapes, and southern winegrowers can now supply good chardonnay, merlot, cabernets, viognier, pinot grigio, syrah, and very appealing blended reds, though it is still necessary to sort out the well-made wines from the inferior. Most southern wineries are small, family-owned operations whose wines are available only locally. One popular way to discover them is the increasing number of wine festivals and tastings held throughout the South.

BARBARA ENSRUD

Durham, North Carolina

Leon Adams, The Wines of America (1990); Barbara Ensrud, American Vineyards (1988); James M. Gabler, The Wines and Travels of Thomas Jefferson (1995); John R. Hailman, Jefferson on Wine (2006); Thomas Jefferson, The Garden and Farm Books (1987).