Shakespeare and Fletcher’s late play about the reign of Henry VIII enjoyed great popularity historically and hence has a complete and continuous stage history. Originally designed perhaps to celebrate the marriage of James I’s daughter, another Princess Elizabeth, to Frederick V, the Elector Palatine, in the summer of 1613, it has been regularly revived for spectacular royal occasions ever since. Evidence of its early performance and reception exists in several accounts recording the disastrous performance on 29 June 1613, when one of the cannons set the Globe’s thatch alight. Sir Henry Wotton’s letter of 2 July 1613 offers a detailed account of its staging, as well as voicing his concerns about its manner of representing “greatness” on stage, making it “very familiar, if not ridiculous”:

I will entertain you at the present with what happened this week at the Banks side. The King’s players had a new play called All is True, representing some principal pieces of the reign of Henry the Eighth, which set forth with many extraordinary circumstances of pomp and majesty even to the matting of the stage; the knights of the order with their Georges and Garter, the guards with their embroidered coats, and the like: sufficient in truth within awhile to make greatness very familiar, if not ridiculous. Now King Henry making a Masque at the Cardinal Wolsey’s house, and certain cannons being shot off at his entry, some of the paper or other stuff, wherewith one of them was stopped, did light on the thatch, where being thought at first but idle smoak, and their eyes more attentive to the show, it kindled inwardly, and ran round like a train, consuming within less than an hour the whole house to the very ground. This was the fatal period of that virtuous fabrick, wherein yet nothing did perish but wood and straw, and a few forsaken cloaks; only one man had his breeches set on fire, that would perhaps have broyled him, if he had not by the benefit of a provident wit, put it out with a bottle of ale.64

Despite this setback, the play remained popular, due to its combination of the treatment of relatively recent history and gorgeous spectacle. It was revived at the rebuilt Globe at the request of George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, on 29 July 1628.

After the Restoration and reopening of the theaters in 1660, Henry VIII was one of the few Shakespearean plays to be regularly staged. Bookseller and actor Thomas Davies records how Thomas Betterton was coached in the part of Henry by William Davenant, a godson of Shakespeare’s, who had been instructed by John Lowin, a member of the King’s Men. John Downes, Davenant’s company bookkeeper records that Betterton was “all new Cloath’d in proper Habits” for the role.65 According to William Winter, “Betterton’s performance was accounted essentially royal, and the example of stalwart predominance, regal dignity, and bluff humour thus set has ever since been followed.”66 He was succeeded in the part by Barton Booth, Charles Macklin, and James Quin, suggesting that Henry was regarded as the star part, although Colley Cibber’s Wolsey was noted and praised.

Cibber mounted productions at Drury Lane between 1721 and 1733. His 1727 revival included a notable coronation procession at the beginning of Act 4, designed to coincide with the coronation of George II. David Garrick’s 1762 staging for the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane was similarly spectacular, boasting a cast of more than a hundred and thirty for the coronation scene. Emphasis on the pageantry of the play necessitated cuts to the text, a practice that continued as elaborate spectacle came to dominate productions. At the same time, criticism of the play’s language and structure were voiced.67 In a discussion of John Philip Kemble’s 1811 production, the Times’ critic suggests that Shakespeare had been called on to create a piece of hackwork, designed to “palliate … adultery,” and “obscure” Katherine’s memory and Henry’s “gross caprices”:

Processions and banquets find their natural place in a work of this kind; and without the occasional display of well-spread tables, well-lighted chandeliers, and well-rouged maids of honour, the audience could not possibly sustain the accumulated ennui of Henry the Eighth.68

The reviewer adds that “The banquet deserved all the praise that can be given to costly elegance. It was the most dazzling stage exhibition that we have ever seen,” and goes on to praise the performances of Kemble and his sister, Sarah Siddons: “If Mrs. Siddons and Mr. Kemble desired to show the versatility of their powers, they could not have chosen more suitable parts than Katherine and Wolsey.”69 It became one of Siddons’ best-known and loved roles:

The grandeur of the actress as Queen Katherine, her air of suffering and persecution, enlisted a new order of sympathy, and the well-known denunciation of the Cardinal, like her famous scene in Macbeth, became inseparably associated with herself.70

Katherine and Wolsey were now seen as the leading roles and the first three acts alone were performed. Edmund Kean’s Wolsey was highly praised in his 1822 and 1830 revivals. William Charles Macready played Wolsey from 1823 to 1847 in productions notable for the great actresses who played Katherine, including Helen Faucit, Charlotte Cushman, and Fanny Kemble. For the royal “command” performance of Acts 1–3 at Drury Lane on 10 July 1847, Macready played Wolsey to Charlotte Cushman’s Katherine and Samuel Phelps’s Henry, in the presence of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert.

Phelps himself played Wolsey in his stagings at Sadler’s Wells in 1845 and 1848, after which date he included Act 4: the staging on 16 January 1850 was given to help raise funds for the Great Exhibition of 1851. He revived the play another four times between 1854 and 1862. By far the most successful Victorian production, however, was Charles Kean’s 1855 spectacular with himself as Wolsey and his wife, Ellen Tree, as Katherine. The twenty-three-year-old Lewis Carroll recorded in his diary that it was “the greatest theatrical treat I ever had or ever expect to have—I had no idea that anything so superb as the scenery and dresses was ever to be seen on the stage.”71 Kean retained most of the first three acts, “but to allow time for the many processions and tableaux, which included an actual coronation, Acts 4 and 5 contained little else.”72 It was Katherine’s vision of Act 4 Scene 2 that seems to have produced the most striking effect:

But oh, that exquisite vision of Queen Catherine! I almost held my breath to watch; the illusion is perfect, and I felt as if in a dream all the time it lasted. It was like a delicious reverie, or the most beautiful poetry. This is the true end and object of acting—to raise the mind above itself, and out of its petty everyday cares—never shall I forget that wonderful evening, that exquisite vision—sunbeams broke in through the roof and gradually revealed two angelic forms, floating in front of the carved work of the ceiling: the column of sunbeams shone down upon the sleeping queen, and gradually down it floated a troop of angelic forms, transparent, and carrying palm branches in their hands: they waved these over the sleeping queen, with oh! such a sad and solemn grace.— So could I fancy (if the thought be not profane) would real angels seem to our mortal vision …73

The top angel in the vision was Ellen Terry.74 Kean’s last performance on the London stage was as Wolsey on 29 August 1859. Phelps too made his final appearance in the part in the revival at the Royal Aquarium in 1878 when he “all but collapsed at the end of his final speeches” and had to be “helped off stage when the curtain fell.”75

In his stage history, George C. D. Odell suggests that Henry Irving’s production at the Lyceum in 1892 was “Undoubtedly the greatest—if not the only—Shakespearian ‘spectacle’ that Irving ever attempted.”76 The richness and accuracy of costumes and sets were much admired, as were the performances of the strong cast. Irving’s was an “original conception” of Cardinal Wolsey that “differed radically from that of most of his famous predecessors, and constantly challenged attack and admiration. Certainly it was not the Wolsey of tradition, but forceful intellect was in every fiber of it.”77 Ellen Terry’s Katherine was similarly admired: “It had not the somber touch of tragedy that should ennoble it, but it was womanly to the core and thoroughly royal in deportment.”78

Despite his innovative interpretation, Irving continued the tradition of giving most of the first three acts, but only those parts of the final two that added to the spectacle. Herbert Beerbohm Tree at His Majesty’s Theatre was similarly cavalier in his handling of the text, justifying his decision in an essay of 1920: “Henry VIII is largely a pageant play. As such it was conceived and written; as such did we endeavour to present it to the public.” For this reason, “It was thought desirable to omit almost in their entirety those portions of the play which deal with the Reformation, being as they are practically devoid of dramatic interest and calculated, as they are, to weary an audience.”79 Tree argues this practice was vindicated by the Prologue’s reference to “two short hours.” Nevertheless reviews make it clear that the drastic cutting of the text did not have the desired effect of speeding the production up:

Much cut, for Tree removed the whole of the last act and ended at Anne Boleyn’s coronation, the play nevertheless occupied four hours: the stage staff of His Majesty’s, trained though it was, had to toil frantically to construct Wolsey’s ostentatious palace, the hall in Blackfriars where Katherine was tried, and Westminster Abbey itself.80

Despite this, Tree’s production enjoyed tremendous success, running for a record-breaking 254 performances until 8 April 1911 and earning him this plaudit from Sporting Life: “He has achieved that which a few years ago was considered impossible—he has made Shakespeare popular.”81 A twenty-five-minute silent film of this production was made, but all copies were sadly destroyed after six weeks of special cinematic exhibition.

Early-twentieth-century productions continued the tradition of spectacular stagings. Ben Greet’s for the tercentenary celebrations of Shakespeare’s death at the Stratford Memorial Theatre and the Old Vic was revived two years later in London with Russell Thorndike as Wolsey and Sybil Thorndike as Katherine. Tree had cut the last act completely, moving straight from Katherine’s death to Anne’s coronation. Such practices were rendered less justified by changing critical perceptions; the work of the eminent scholar E. K. Chambers exposed the subjective nature of the verse tests applied by the “disintegrators” (scholars who held that many of Shakespeare’s plays were not written by him but revisions of, or collaborations with, other writers), which argued that Shakespeare was responsible for most of Henry VIII. Robert Atkins’s 1924 production at the Old Vic, despite staging the complete text, took less time than Tree’s four-hour marathon. Atkins was influenced by the ideas of William Poel and the Elizabethan Stage Society who attempted to recreate Elizabethan staging practices. Use of the complete text rekindled interest in the role of Henry, evidenced in Tyrone Guthrie’s casting of Charles Laughton in the part in his 1933 production at Sadler’s Wells, with Flora Robson as Katherine.

7. 1910, Herbert Beerbohm Tree production. “[T]he stage staff … had to toil frantically to construct Wolsey’s ostentatious palace, the hall in Blackfriars where Katherine was tried, and Westminster Abbey itself.”

The play has never enjoyed great popularity in America; it was first performed in 1799 at New York’s Old Park Theater. There was a production at the same theater in 1811 with George Frederick Cooke as Henry, and another in 1834 with Charles Kemble as Wolsey and his daughter Fanny, then twenty-three, as Katherine. Four years later a production was staged at the National Theater, Church Street, New York, and another in 1847 at the old Bowery Theater with Eliza Marian Trewar as Queen Katherine. Many of the best-known British productions including Kean’s, Macready’s, and Irving’s were also seen briefly in America. The notable American actress Charlotte Cushman, whose “Queen Katherine was the consummate image of sovereignty and noble womanhood, austere and yet sweetly patient,”82 also played the part of Wolsey in 1857. Edwin Booth played Wolsey in 1876 in a four-act version at the Arch Street Theater, Philadelphia, and revived it for Booth’s Theater, New York, in 1878.

Despite its relative lack of success in America, in 1946 Margaret Webster inaugurated the American Repertory Theater’s first season at the International Theater with Henry VIII, in her attempt to create “an American Old Vic.”83 Webster’s direction received praise as did David Ffolkes’ designs, but the production overall was not a success: “The fact that a play not seen in New York in this century was used as an opening guy seemed most hopeful. Indeed the production itself was a fine one.”84 Webster reduced the play’s five acts and sixteen scenes to two acts and thirteen scenes.85 The result was “a vivid and smooth-running production full of colour and pageantry,”86 but although it played in repertory throughout the winter, at the end of the season the American Repertory Theater was forced to close. Theater historian and critic Linda McJ. Micheli argues that “Webster’s Henry VIII stands somewhere between nineteenth-century ‘scenic Shakespeare’ and the ‘Elizabethan Shakespeare’ championed by William Poel and others in regional and academic theaters since the early 1900s.”87

Micheli suggests the production is

illuminated by comparison with Tree’s 1910 production, a spectacular culmination of the scenic tradition, and Tyrone Guthrie’s Stratford production of 1949, which introduced mainstream audiences to many of the “new ideas” we now take for granted—a thrust stage, an emphasis on continuity and brisk pace, a respect for the full text, a de-emphasizing of spectacle and solemnity.88

Webster’s production, she concludes, was “[o]n balance … closer to Tree’s than to Guthrie’s.”89

Guthrie’s 1949 Stratford revival is generally regarded as the most significant of the twentieth century, which managed to unify the play by inspired design and directorial decisions. Tanya Moiseiwitsch’s set contrived an “excellent compromise between a platform and a picture frame stage … with its varied levels, its ample forestage, fifteen feet deep, and its well-thought-out modifications and rearrangements of the gallery and the inner-stage.”90 Reviewers all comment on the “fluidity of movement and the power and the pace thus given to the action”:91

the fluid staging which juxtaposed a scene of downfall with one of spectacular rise. The music of the masque … is still in our ears when the muffled drums usher in … the somber procession of Buckingham on his way to execution. Later, as the fallen Wolsey goes off down the center stairs leading into the orchestra pit, the excitement about Anne’s coronation begins on the main stage.92

Both Prologue and Epilogue were spoken by the Old Lady (Anne Bullen’s friend): a device that divided critics. Guthrie stressed the central role of Henry: “Admirably played by Anthony Quayle … Henry dominated the scenes, huge, hot-tempered but human, a mixture of strong-willed sovereign and pouting schoolboy, a pleasure-loving king but a conscientious one, with true Tudor warmth and directness.”93 For Muriel St. Clare Byrne, Diana Wynyard’s Katherine “made one feel as if it were being spoken for the first time” while the “test” of Harry Andrews’s conception of Wolsey was “that the nearer he came to the audience the better I liked his performance.” His Wolsey she thought “just as good as the author meant him to be.”94 Even one of the few critical reviews admits that “Mr. Guthrie made Henry VIII a good show” while lamenting “but that is about all he did do; the nuances of character and the play’s general conception seemed to have escaped him.”95 Such a negative assessment was very much in the minority though and the play was revived with a new cast at the Old Vic in 1953 to celebrate the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II.

Guthrie was again lauded as “our most flamboyant producer” of a “dazzling production” that

made full use of the topical humours of the text. The three onlookers at the Coronation of Anne Boleyn, munching Tudor sandwiches and spotting the Earl Marshall, had a contemporary ring, and at the christening of the Princess Elizabeth which ends this play few can have failed to be moved by the sense of occasion.96

Public tastes have changed since then and the play has fallen into disfavor, with fewer and fewer revivals and longer periods between them. The most significant from the RSC are discussed below. While Shakespeare’s play has become less popular than at any time in its history, the same cannot be said for its main protagonist, Henry VIII. Fascination with Henry, especially his six wives, and with Tudor history in general, has produced new plays as well as numerous films and television programs about the period and its colorful cast.

The 1979 televised version for the BBC TV Shakespeare Collection, directed by Kevin Billington, is widely regarded as one of the most successful in this series. It opted for a “documentary approach”97 with “a sustained insistence on authenticity of visual impressions and on vocal naturalism.”98 Much of it was shot in “authentic” historical locations, using close-ups and techniques that highlighted the play’s intimacy in contrast to the grand pageantry of stage productions: “while traditional staging has exaggerated scenic effects to the disadvantage of the ultimate private and personal issues towards which the play progresses, television can correct the imbalance by its concentration on the individual’s inward condition.”99 The strong cast with John Stride as Henry, Timothy West as Wolsey, and Claire Bloom “memorably cast as Queen Katherine”100 won unanimous praise.

Brian Rintoul successfully paired Shakespeare’s play with Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons about Thomas More, cross-casting the actors playing the king, Cranmer, and Norfolk, in his production for Canada’s Stratford, Ontario, Festival in 1986. The juxtaposition illuminated both plays; one reviewer concluded that it drew attention to the ways in which “Shakespeare chooses to sacrifice the extremes of noble idealism and diabolical intrigue.”101

In his 1991 production of Shakespeare’s play for the Chichester Festival, Ian Judge cast Keith Michell, who had played Henry with great success in the BBC television miniseries, The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1970) in the title role. It received universally unfavorable reviews with reviewers finding Michell inadequate to the demands of the part on stage:

the Chichester stage has a rather larger acreage than most television sets, and Shakespeare and Fletcher make greater demands on the voicebox than most screenwriting teams. How does Michell’s Henry VIII cope with a challenge he has, as it happens, never faced before? Not much better than anybody else in Ian Judge’s lacklustre production.102

Mary Zimmerman’s production for another festival, the 1997 New York Shakespeare Festival at the Delacorte Theater in Central Park, was more successful and more warmly received. It was significantly the last play in the Public Theater’s thirty-six-play Shakespeare Marathon, started by Joseph Papp nine years earlier. Zimmerman’s “efficient, often elegant” direction produced a “streamlined staging that’s almost miraculous in untangling the convolutions of the story.”103 The period costumes were shown to good effect against a “set of connected archways, shrinking in perspective and painted a lush royal blue … lovely in its classic simplicity.”104 The New York Times’ critic suggested that “the disparate nature of the play” was highlighted by the cast’s “varied styles of acting”105 and speaking. In his view, Jayne Atkinson’s Katherine was the outstanding performance, a judgment the elements concurred with on press night:

The trees in the park seemed to sigh in sympathy as Katherine, played by Jayne Atkinson, presented her case to a less than sympathetic court; the documents in the hands of Katherine’s nemesis, the ambitious Cardinal Wolsey (Josef Sommer), threatened to blow away, and as the words of the menaced queen melted from offended dignity into regal anger, there was little question which side the angels were on in this trial.106

In 2003 Granada television produced an updated version “without any cod Tudor language” or “ludicrous dancing in pantaloons” which was “partly inspired by The Sopranos” and starred Ray Winstone, “one of our seminal screen hard nuts,”107 as a “gangster king” Henry. There was yet another festival production at Stratford, Ontario, in 2004 directed by Richard Monette described as “another solid offering … except for a few gratuitous trappings of self-indulgence including a couple of fruity gentlemen and a dream masque.”108 Seana McKenna’s Katherine was again judged the “most attractive figure in the play” and her “powerful and deeply moving” performance conveyed “fierce dignity.”109

For the 2006 Complete Works Festival of all Shakespeare’s plays, the RSC invited AandBC Theatre Company to present their touring production of the play in the historic venue of Stratford’s Holy Trinity Church, the same church where the playwright was both baptized and buried. It proved an inspired setting:

The mellowing evening sun pours in through the stained glass windows on a staging that arranges the audience along the nave like a parliament or congregation in two opposing banks of raked seating. This leaves a lengthy, narrow acting area … though spectators may succumb to Wimbledon Neck as their attention is swivelled from one end to the other.… 110

Director Gregory Thompson exploited the challenge it presented: “The audience’s proximity to the acting space serves the play well as audience members are literally drawn into the action by being selected to hold props and serve as members of the jury.”111 Audience members thus enhanced the versatile cast of fifteen. Dressed in period costume, the staging was “lavish” with an emphasis on spectacle:

Fireworks interrupt Wolsey’s feast as Henry’s disguised revellers swarm into the church. During their entrance, one of the merry company memorably performs a lewd dance with one of the female audience members in the front row.112

At the play’s center was “Antony Byrne’s fine, red-bearded, ambivalent Henry.”113 Corinne Jaber was praised as an “unusually fierce Katherine of Aragon, hurling herself on the floor of the nave in front of the king, [who] dies like a political martyr.”114 Animal metaphors sprang to several critics’ minds when describing Anthony O’Donnell as a “toad in red silk”115 or a “scarlet slug sliding to the top of the pile over the bodies of his victims.”116 The two undoubted stars of the evening, though, were the seven-month-old Alice Wood as Princess Elizabeth—“an alert, silent, lovely child who had the audience spellbound,”117 and the venue itself, which lent the play “a sombre, melancholy grandeur.”118 Gregory Thompson discusses the production and the challenges he faced in “The Director’s Cut” below.

Reviews of the 2010 production at Shakespeare’s Globe directed by Mark Rosenblatt all advert to the disastrous fire of the 1613 staging at the original Globe. While several critics still feel the need to apologize for the play, Paul Taylor of the Independent describes how Rosenblatt’s sophisticated direction managed to

pull off the considerable trick of giving full due to the nostalgic, propagandistic elements in this Shakespeare/Fletcher collaboration, while also highlighting and extending the flickering moments of subversive acknowledgement that there is a much less “official” version of events which cover the contentious birth of the English Reformation. So though the production pulls all the stops out in a blaze of mitres, ivory silk, boy choristers in the gallery, and trumpet acclaim for the culminating baptism and Cranmer’s prophecy of future national glory, there turns out to have been a cunning optical illusion here that cuts the sequence down to size.119

Dominic Rowan’s “trim, darkly handsome and enigmatic”120 Henry was praised for “wit, energy and sudden enlivening moments of menace,”121 while Kate Duchêne’s Katherine of Aragon as “a foreign-accented outsider” proved “awesomely fiery and confrontational.”122 Miranda Raison’s Anne brought “a welcome dash of sex appeal to the fusty proceedings” while Ian McNiece’s “grotesque Cardinal Wolsey … hisses out his lines like a poisonous snake and slithers across the stage like a disgustingly plump slug.”123 Reviews also picked out

Amanda Lawrence’s triple whammy of splendid cameos [which] add up to a brilliant bluff-calling device. A snipe-faced Welsh eccentric, she’s the lady-in-waiting who disputes Anne Boleyn’s pious disavowal of any yearnings to be queen. She also plays the silent white-faced Fool who, in Rosenblatt’s version, shadows the King with a puppet of his deceased son.124

The most controversial decision that a director can take in relation to Henry VIII seems to be to stage the play at all. Its combination of reportage and pageantry has left critics confused and divided: the terms “whitewash” and “Tudor propaganda” recur constantly. All three RSC productions—Trevor Nunn’s in 1969, Howard Davies’s in 1983, and Gregory Doran’s in 1996—have provoked undisguised hostility from some critics who use its joint authorship (with John Fletcher) and seeming refusal of moral condemnation as sticks with which to beat it:

Henry VIII is an odd play. Why Shakespeare wrote it is a mystery. Whether he wrote it is another. And why Trevor Nunn should have chosen to stage it, in what is without exception the most amazing production I have ever seen at Stratford, is a question which may well vex the scholar in decades to come.125

When he came to write a play dealing with a Tudor monarch in person … Shakespeare found himself having to sacrifice all artistic integrity for crude propaganda.… Instead of courageously meeting the problem head-on, Shakespeare wrote one of the worst plays ever penned, playing safe by creating a rogueish [sic] but loveable King, surrounded by councillors of varying degrees of integrity who pose no real threat to his majesty.… There is no earthly reason why anyone should read, see or produce this play.126

Ninety years ago, when Britain still ruled most of the waves, you can imagine Greg Doran’s bizarre production of Henry VIII would have been acclaimed as a sumptuous celebration of England’s Tudor royalty and the glories of the new Protestant supremacy. But to see a Golden Heritage approach seriously adopted in 1996 to this weak chronicle-pageant play, which Shakespeare wrote with John Fletcher, beggars theatrical belief.127

Henry VIII is seen then as something of an ideological “problem play.” Hugh M. Richmond analyzes what he regards as some of the dilemmas it poses for directors:

Moral concerns have persisted … for every audience of Henry VIII since 1613. They constitute the familiar context which attends the play with its sustained dramatic irony: unexpressed but omnipresent in every audience’s awareness.… Any successful production must communicate this final delicate balance of the sinister and the hopeful, without slipping into a naïve proclamation of one or the other in the last scene. The sustaining of this elusive tone constitutes the unique challenge which the play proposes in production.128

Directors have risen to this challenge in a variety of ways in the face of critical hostility. Historically productions had focused on the play’s pageantry and the leading roles of King Henry, Katherine of Aragon, and Cardinal Wolsey. Trevor Nunn was reacting against such a conventional approach in his 1969 production, which employed a modern set and production style while locating the play within the context of Shakespeare’s other late plays. In his program notes Nunn argued that “They do not idealise the human condition, the beast is there alright, so also is the angel. Man is in search of ripeness or grace or … self-knowledge. In the late plays grace is achieved through love.”129 According to John Barber such a context revealed that

Henry VIII … is held together and sustained by the same themes as in the other late works: pity for the unjustly used and hope that a new generation will right ancient wrongs. Thus the newborn Elizabeth is only another Perdita or Miranda.130

This reconciliatory conclusion though seemed at odds with a consciously political interpretation, set against the backdrop of 1960s political radicalism and a production style most often described as “Brechtian.” It was played within a black box with “a fine, heavy, Elizabethan castle hung against a black backdrop and lit ingeniously to give it varying degrees of depth.”131 Other critics were less complimentary. Irving Wardle referred to the set as “a permanent toytown backdrop of Tudor London.”132 He was one of many to be irritated by the self-conscious “series of newspaper headlines that flash up before every scene.”133 These were subsequently dropped in the London revival.

Wardle speculated that the captions were one of the techniques deployed, “meant to establish a link between modern spectators and the ordinary citizens who carry so much of the play’s narrative.” But, he concluded,

attitudes to Royalty have changed so much that the link is more ironic than direct. Apparently this is not intentional, as the production finishes with rapt invocations to peace and plenty which are meant in earnest even though they do transpose the finale from blazing ceremonial into the mood of a gentle masque.134

Various strategies were employed to engage audience participation. In Act 2 Scene 1 in the discussion between the two Gentlemen, on the line “We are too open here to argue this” the promptbook reads “They clock audience.” Direct address was used “in the manner of the music-hall”135 and there was a “splendid football match in which Emrys Jones’s Archbishop Cranmer takes a penalty kick after the ball has been neatly returned to the stage from the front stalls.”136 This scene did not, however, impress all the critics with its splendor:

in period productions (and this one is no exception) there is invariably a varlet whose breeches fall down, supported, for reasons seldom clear, by quantities of disagreeably self-conscious small children. It is nervous work watching Cranmer dribbling a woolly ball with these juveniles as he waits (“like a lousy footboy at chamber door”) before his trial; worse is to come when the peers in council, routed by the king, line up to pass the same ball embarrassedly from hand to hand, as in a number rather low down on the bill at the Palladium. Mr. Nunn has shown signs before of an alarming weakness for woolly balls, but never on such a scale as this.137

Ronald Bryden in The Observer described the end of the production: “a sonorous white hippie mass in which actors advance on audience, chanting Cranmer’s wishes for England’s prince’s ‘peace, plenty, love, truth.’ ” He regards this as a “triumphant close”138 to Trevor Nunn’s first season. D.A.N. Jones in The Listener was less convinced:

When Cranmer makes his final great speech, that Blake-like vision of a future England of “peace, plenty, love, truth,” Nunn uses a modern style for expressing rapture. You know those modish camp-meeting songs, “That’s the way God planned it” and “Oh happy day, when Jesus walked,” and the mantras of the Hare Krishna group. In this mood, Nunn sets his actors to surge toward the audience chanting the four pleasing words. I think this over-softens a tough play. They have left out the fifth word: “terror.”139

In retrospect, theater historian Hugh Richmond judged it “one of the most thought-provoking productions of this century.”140

Nunn’s production was seen as radical and modern. Howard Davies’s was if possible even more so and again the epithet “Brechtian” crops up repeatedly in discussions of his 1983 production. The play’s politics were again emphasized, with the program notes’ inclusion of an extract from R. H. Tawney’s Religion and the Rise of Capitalism. In Davies’s view the play “is very much a modern play, dealing with taxes, unemployment and social divisions.” His production was clearly glancing at the right-wing politics of Margaret Thatcher’s government in the 1980s. The theme of the bureaucratization of a centralizing Tudor state was literalized in the opening scene. Nunn had cut both prologue and epilogue (as well as engaging in considerable textual pruning). Davies’s production started with King Henry alone on stage scattering papers and speaking the prologue himself.

Irving Wardle describes the stage as “well and truly alienated. Hayden Griffin’s sets consist of enlarged reproductions of Elizabethan street scenes and architectural perspectives, trundled along traverse rails and suspended well above the stage floor.”141 Davies was keen to reveal the reality beneath the surface and like Nunn eschewed traditional pageantry, but “in passages like the masque of Katherine’s dream and the staging of the coronation ritual with a group of robed dummies, it supplies something no less visually exciting than conventional pageantry.”142 Katherine’s dream was a ghostly dance lit by ethereal blue light. For Anne’s coronation Davies incorporated the Folio’s detailed stage directions as a dress rehearsal for the real thing. Its pace and energy succeeded as Wardle suggested but it also underlined the insubstantiality of the royal pageant. The Epilogue was delivered by Queen Anne amid more paper being thrown into the air and a whistle blowing “time.”

Discussing Davies’s 1983 production James Fenton argued, “Truly to shock a modern audience, one would need to go back to that old tradition of pageantry and choristers, historicism and authentic sets.”143 Gregory Doran contrived to do this with his 1996 production explaining the theatrical context for doing so in the program notes:

Tyrone Guthrie directed a series of energetic productions of the play which re-emphasised the role of Henry.… Trevor Nunn’s 1969 production by contrast … reworked the play in an austere Brechtian frame which foregrounded the play’s bleak politics. The most controversial twentieth-century production has been that of Howard Davies at Stratford in 1983 which offered a postmodern resistance to pageantry emphasising the play’s profound ambivalence over the slippery concepts of “truth” and “conscience.” It is arguably only in the wake of Davies’s production and its deliberate resistance to the legacy of splendour that Henry VIII can be taken beyond these contrasting and controlling modes, recovered as a Jacobean play, and re-invented for the twenty-first century.144

Presumably the term “Jacobean play” implies one that combines spectacle and pageantry (as in the Jacobean masque) and yet is deeply political at the same time. Doran was largely successful. Michael Billington thought the production in the Swan made “good use of the space’s opportunity for intimate spectacle.”145 Shaun Usher was alert to both elements:

We begin with the splendid tableau of a gilded king out-dazzling even the Field of the Cloth of Gold—equal honours here to Robert Jones and Howard Harrison for set and lighting—but like the climactic set-piece of Elizabeth I’s christening, the picture lingers only long enough to impress. Then it’s on with the power struggles, Henry versus pious Catherine (sic), Cardinal Wolsey versus The Rest.146

Billington also describes the way in which politics and spectacle worked together in this production:

In its last outing in 1983 Howard Davies treated the play as a cynical Brechtian anatomy of power politics: a piece of mocked Tudor. Doran, presumably in a spirit of irony, blazons the play’s original title, All Is True, across the back-wall and the Stratford programme; the result is not so much to heighten the play’s documentary reality as to make you aware how everyone bends the idea of truth to his own purposes.… Truth, in short, is a malleable weapon rather than a fixed commodity.

Doran and his designer, Robert Jones, also seek to give the play visual unity by showing Henry periodically emerging from a recessed chamber in golden triumph while brutal realpolitik takes place on the forestage.147

In Shakespeare in Performance, Richmond argues that this is a play that, given its historical specificity, needs to be staged in “historically accurate costume.”148 The designers for all three productions have agreed with him and taken the well-known portraits of the chief protagonists as their inspiration, notably the Holbein portrait of Henry. Both Nunn’s and Doran’s productions were sumptuously costumed. Deirdre Clancy in Howard Davies’s production designed authentic period costumes but in subdued tones of gray and oatmeal suggesting “not Holbein’s oils but his drawings.”149

In his autobiography, Donald Sinden, who played Henry in 1969, recalls the assembled cast at the end singing a magnificent “Gloria.”150 In Doran’s production Henry had emerged in his first golden pageant to the magnificent choral singing of “Exultate, Jubilate.” The masque at the Cardinal’s took some by surprise: “Wolsey’s priapic house-party staggered some of the audience, but manifestly suggested the Cardinal’s vulgarity.”151 It took on demonic overtones as it emerged from and eventually exited via the trapdoor.

The most controversial and original music was by Ilona Sekacs for Davies’s 1983 production. Pastiche Kurt Weill, it acted as punctuation between scenes and suggested a parallel with the decadent court of the Weimar Republic: “the music, content sometimes to endorse the pathos, is often sharp and derisive, alerting us to ironies.”152 The dance in the masque at the Cardinal’s was a somewhat anachronistic tango in which the fate of women in the play could be read from Henry’s brutality in “Haling Anne Bullen to her feet,” a fate “not only symbolized but determined in that court dance which whirls women round and throws them away. The men rise and fall, the women are taken and discarded.”153

In Sir Henry Wotton’s description of the burning down of Shakespeare’s Globe when the thatch caught light from a celebratory cannon during a performance of this play, he voiced the objection that its realist dramatic qualities were “sufficient in truth within a while to make greatness very familiar, if not ridiculous.”155 Many critics since have been disconcerted by its “low-key emotions and intimate verbal style”156 which creates a sense of the ordinariness and realism of the characters, but has subversive potential: “it images directly the contradiction between the sacred royal office and the fallible human individual who holds it, making historical actions intelligible as everyday transactions.”157

Historical productions of the play focused on pageantry and featured the roles of Katherine and Wolsey as star vehicles. The role of the king has tended to provoke controversy because Shakespeare’s Henry is not the monstrous Bluebeard of popular myth. Richmond argues that “At this pivotal point in his career Henry’s role must remain as unclear, even incoherent, as it probably seemed to its original audience—and just as bewildering as contemporary politicians often appear to us now, without the advantage of hindsight.”158

Despite describing the part of Henry as “a stinker,”159 Donald Sinden was able to utilize his natural charm and charisma in the part in Nunn’s production and win over most of the critics. He believed that the play showed “only a veneer of the truth” and found “all the speeches ambiguous.”160 Richmond thought that “This tension between surface characterisation and the latent reality known to the audience by hindsight is what lent memorable force to Sinden’s performance.”161 Many critics commented on the paleness of his makeup (and all commented on half his beard coming off during the trial scene on the opening night). K. E. B. of the Nottingham Evening Post found Sinden “a Henry of distinction and, praise be not over-padded. His gradual accession of authority from the time that Wolsey dominated and deceived him until he emerged as the ruler in fact as well as in name, bluff but not blustering, was a delight to watch.”162

Nunn had dispensed with Prologue and Epilogue. This is Sinden’s own description of the ending:

At the end of the play … the assembled characters sang a magnificent “Gloria” and then left the stage in stately procession. Only Henry remained in a spotlight, holding the infant Elizabeth who had just been christened. Here I tried to do a most difficult thing. The end of the play is a cry for peace in the time of the future Elizabeth I and in a few brief seconds I, as Henry with no lines, looked into the future, saw the horror that was to come, questioned why, realised the failure of the hope, crashed into the twentieth century and pleaded silently that where the sixteenth century had failed, those of the future may succeed. Many people told me it was a most moving moment.163

Richard Griffiths, who played the part in Davies’s 1983 production, is on record as calling Henry VIII “a belting good play,”164 and was proudly proclaimed as the only actor to play the part without padding. He played Henry in a deliberately naturalistic way, in keeping with the downplaying of the pageantry. Ned Chaillot thought he made him “a likeable rogue,”165 while J. C. Trewin suggested, “There will probably be argument about Henry, as Richard Griffiths presents him; but it is a pleasure to have a King who is not simply an angry boomer behind a Holbein mask.”166 Sheridan Morley, however, complained that he “never inspires the remotest terror or authority.”167

Paul Jesson in Doran’s production, which played up the pageantry, attempted more bluffness while at the same time making Henry human. As Benedict Nightingale saw it, Paul “Jesson’s splendidly bluff, blunt King learns to see through fake and value honesty,” and he goes on to blame Shakespeare for Henry’s lack of villainy, complaining that “The principals are all relentlessly good mouthed.”168 Shaun Usher found it an impressive performance:

Jesson has the presence to fulfil that wide-as-he-is-tall image from the school history books, and the skill to convey arrogant yet sentimental sensibility with deep veins of deviousness and humbug. Previously, Henrys have been upstaged by Catherine of Aragon, or dwarfed in surrounding pageantry; Jesson is never in danger of being deposed.169

Queen Katherine was played in the past by theatrical legends such as Sarah Siddons, Ellen Terry, Sybil Thorndike, and Edith Evans. The part requires intelligence, spirit, dignity, and pathos: a part “Dame Peggy Ashcroft seemed born to play.”170 She brought great personal commitment to the role and, according to Trevor Nunn, felt the play did less than justice to Katherine’s historical dilemma and hence attempted to incorporate extra material from the transcript of the trial, which he vetoed. Ashcroft, by common consent, triumphed. John Barber singled hers out as “the one outstanding performance of the night,” describing how,

When besotted with Anne Bullen, the King spurns his Queen; she reacts first with fire then with melancholy, at last with a pitiful pride. The actress finally came to resemble a Rembrandt portrait of a shrivelled old lady. She speaks always like a queen and even when dying and desolate can hang a word on the air like a jewel.171

Keith Brace was also struck by her final scene:

Dame Peggy more or less created her own play in the death of Katherine, where the emotions aroused were out of proportion to the actual emotional content of the words spoken. She carried the scene at her own slow, but never wearying pace. It was, ironically, more Brechtian as a statement about death rather than a re-enactment of death than all those silly headlines.172

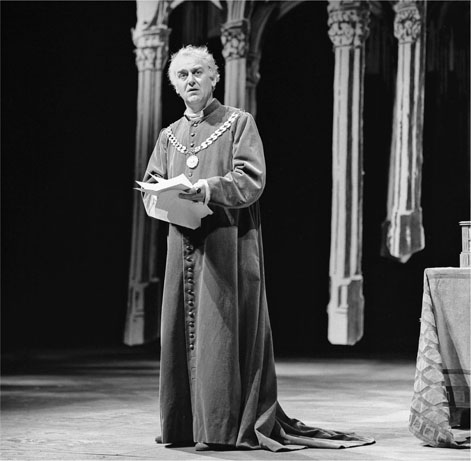

8. 1969, Trevor Nunn production. Peggy Ashcroft as Katherine who reacted “first with fire then with melancholy, at last with pitiful pride. The actress finally came to resemble a Rembrandt portrait of a shrivelled old lady.”

Gemma Jones, too, in Davies’s 1983 production made a fine Katherine, intelligent and dignified in standing up for the rights of the people in council, committed to her husband. Davies offered a fuller staging of her celestial vision and, maintaining her dignity, she became a figure of pathos in her death.

Jane Lapotaire played Katherine in 1996, emphasizing her status as an outsider by employing a soft Spanish accent and having her ladies sing and dance sevillanas to a flamenco guitar at the beginning of Act 3. Her Katherine was very human, vulnerable, and angry. Benedict Nightingale thought her “a fine Katherine of Aragon … who brings patience, dignity and, in her final encounter with Cardinal Wolsey, a moving mix of queenly outrage and simple pain.”173 The celestial vision was simply represented by a shining light playing across her, bathing her sleeping figure: “Hers is the pathos of the evening.”174

The chosen part of Kemble, Irving, and Gielgud; it was played in Nunn’s production by Brewster Mason, a huge, intimidating figure and an RSC stalwart. Gordon Parsons thought he played the part “as a benign, scarlet slug of a man,”175 but Charles Landstone thought him “too coarse as Wolsey, bringing sarcasm in place of pathos to his famous dying speech.”176

John Thaw, fresh from his TV success in The Sweeney, played the part in Davies’s production. His performance was not to everyone’s taste: “John Thaw played Wolsey much in the role of a shopkeeper. Even in the lines where his downfall causes him to reject worldly ambition, you feel it wouldn’t take much for him to open his shop elsewhere.”177 Ned Chaillot, however, argued that, “With Mr. Griffiths going lightly from strength to strength, there is room for a touch of the tragic in the characters of Wolsey and Katherine, and John Thaw’s Wolsey achieves the tragic in realizing how ill he has served his God.”178

Ian Hogg, Wolsey in Doran’s production, discussed the play in an interview with the Birmingham Post:

On the rare occasions [the play] is done it tends to be very highly dressed up, because people doubt the power of the text. But Greg Doran, who is directing this production, has relied a lot on the speed of the words, which moves it at a great lick. If you weigh it down with big scene changes you lose that momentum.179

9. 1983, Howard Davies production. John Thaw as Cardinal Wolsey “achieves the tragic in realizing how ill he has served his God.”

Michael Billington saw him as “a chunky Ipswich over-achiever with a cottage-loaf face who undergoes genuine repentance,”180 and Naomi Koppel in the Evening Standard thought that “Ian Hogg steals the show as Cardinal Wolsey, charting the rise and fall of the butcher’s son from Ipswich who cannot quite rid himself of his accent.”181

In all three productions, the three leads were strongly played and well-balanced. Each production also featured outstanding performances in lesser roles.

Richard Pascoe played Buckingham in 1969. Philip Hope-Wallace argued that he delivered his “great speech of farewell to life … as well as I have heard it.”182 Emrys Jones’s Cranmer in the same production brought “a hang-dog charm to the part of Cranmer—his hectic football game with the boys while awaiting questioning by the council is a masterstroke.”183

Queen Anne is a small part without a great deal of scope but in 1969, “Janet Key made Anne Bullen radiantly beautiful, which is about all the part allows.”184 Davies had given the prologue to Henry to deliver and to balance out the proceedings, gave Sarah Berger as Anne the Epilogue. He also made the “Old Lady” younger and added a bevy of other young women in Act 2 Scene 3. Claire Marchionne in Doran’s production made her seem less than demure in the masque at Wolsey’s and brought her on at the end, where she put her hand to her neck, presumably to serve as a visual reminder of her ultimate fate. Cherry Morris’s Old Lady in 1996 was Welsh (as one reviewer commented, there were a lot of accents in this production) and her performance was singled out for its vitality:

as the Old Lady, Cherry Morris is brimful of sheer human essence. By some strange fluke, Shakespeare is at his best in the few lines he gives to this minor character. Listening to her, we are keenly alive in the moment as nowhere else in the play.185

The Chamberlain does not generally get a mention, but Guy Henry’s performance in 1996 was picked out by a number of critics for the sophistication and clarity he brought to the part: “There is plenty of wry humour, particularly in Guy Henry’s Lord Chamberlain, and also in Cherry Morris’s down-to-earth Welsh lady-in-waiting.”186 Perhaps in recognition of their presence onstage as assets, Doran used Guy Henry to speak the Prologue and Morris in place of the Third Gentleman, enlivening the scene while commenting on events such as Anne’s coronation.

Originating perhaps as an occasional play for the wedding celebrations of James I’s daughter Elizabeth, Henry VIII was immensely popular, especially for the celebration of royal occasions, until the twentieth century, when, rather than being played on its intrinsic dramatic merit, it seems frequently to have been relegated to the status of a “festival play” and revived out of a sense of duty. All three RSC productions, though, have proved successful, if controversial, demonstrating that in the right hands it’s still a play with real theatrical virtues:

Truth to life is at once the problem and the fascination of Henry VIII. This play is a controlled and possibly cynical experiment. It may not be artistically great, but it is artistically interesting. Its structure and resolution may be “flawed” by ambivalence, divorce, and disjunction, but … these “flaws” are patterned and full of meaning, controlled and deliberate. They comment on human truth and art, explaining how literally, objectively true to life great art can be.187

Gregory Doran, born in 1958, studied at Bristol University and the Bristol Old Vic theater school. He began his career as an actor, before becoming associate director at the Nottingham Playhouse. He played some minor roles in the RSC ensemble before directing for the company, first as a freelance, then as associate and subsequently chief associate director. His productions, several of which have starred his partner Antony Sher, are characterized by extreme intelligence and lucidity. He has made a particular mark with several of Shakespeare’s lesser-known plays, including Henry VIII in the Swan Theatre in 1996, which he’s discussing here, and King John in 2001, as well as highly acclaimed revivals of works by other contemporary Elizabethan and Jacobean writers.

Gregory Thompson was born in Sheffield and studied mathematics and philosophy at the London School of Economics, before training at Sheffield Youth theater, the National Theatre Studio and Theatre de Complicite. In 1998 he founded AandBC Theatre Company to create touring productions of classical and new drama. These included many productions for Lincoln’s Inn Fields and Somerset House in London. Other productions include Mahabharata, The Winter’s Tale, The Rape of Lucrece, and The Tale That Wags the Dog (a storytelling show about the relationships between men and women). He won a Young Vic’s Jerwood Director’s Award in 2006 and was named Best Director at the 2006 Critics’ Awards for Theatre in Scotland for his production of Brian Friel’s Molly Sweeney at Glasgow Citizens’ Theatre. From 2006 to 2007 Gregory was director of Glasgow’s Tron theater. Here he’s discussing AandBC’s production of Henry VIII, commissioned by the RSC as part of the 2006 Complete Works Festival and performed in the iconic setting of Holy Trinity Church, Stratford-upon-Avon.

Henry VIII was seen traditionally as a great patriotic celebration and was often staged on the occasion of royal coronations; do you think perceptions of the play have changed and might that account for its relative lack of popularity today?

Doran: Howard Davies tells a story about when he directed the play [in 1983]. There was a meeting in which all the plays were being divvied up for the following year and he went out to the toilet. When he came back he discovered that he was directing Henry VIII! When Adrian Noble offered it to me in 1996 various people suggested that it was a poisoned chalice and that it was the one Shakespeare play that doesn’t work. I knew that it had been an excuse for a lot of pageantry, that there had been great productions which had staged not only the execution of the Duke of Buckingham but also his journey to the tower by barge, with whole streets of cheering crowds following the coronation of Queen Anne, and spectacular flights of angels for the dream of Queen Katherine.

When you do plays at Stratford you are always aware of previous productions. I had seen that Howard Davies production with Richard Griffiths (Henry), John Thaw (Wolsey), and Gemma Jones (Katherine) and was fascinated by how they had eschewed that pageantry. I remember that the coronation of Queen Anne was a sort of rehearsal: they had dummies dressed up as the various people and they read the stage directions out loud as dialogue. I shared their sense that pageantry had swamped previous productions of the play. It was my first Shakespeare for the RSC and it was a play and a period that I researched a lot. A very significant point about the pageantry is that it is political propaganda. Right at the beginning of the play the Duke of Norfolk describes the Field of the Cloth of Gold: how the French were “All clinquant, all in gold” and what a spectacular affair it was. But as Buckingham says, it’s “like a glass, / Did break i’th’wrenching”: in other words they had spent an awful lot of money on a Tudor policy of magnificence, and that magnificence was deliberately designed to display wealth and power.

That first scene seems to suggest that the point of the play is in part to demonstrate the hollowness of that policy of propaganda. I began to look at the play from a political perspective in overall terms, but also and particularly at how the pageantry was part of a policy of magnificence. The play also sweeps from the epic to the intimate in a very specific way. My designer, Rob Jones, and I both realized quite quickly that the Swan Theatre itself was going to help us to solve this problem, in that we could present some spectacular pageantry but then lock it away and become intimate.

10. 1996, Gregory Doran production. “[T]he pageantry was part of a policy of magnificence. The play also sweeps from the epic to the intimate in a very specific way.”

Thompson: I think one of the problems with the play is that it is seen as a great patriotic celebration and without care the pageantry can obscure what story there is. The play deals with a tricky piece of our history: Henry VIII was a ruthless tyrant and, in the last fifteen years of his reign, an unstable capricious despot. In many ways the play is about how dangerous it is to be in the court of a tyrant.

Much of the impact of the play has been lost, of course, because for the most part the modern audience no longer has sufficient knowledge of Tudor politics to be aware of the absences and omissions of people and events. Even so, we still recognize today that in the play there is only a hint of Henry’s desperation for an heir; no real debate about the legality of his marriage to Katherine; no mention of him becoming Supreme Head of the English Church; four of his wives are missing and no wives are beheaded.

I think the relative lack of popularity of the play is due to its episodic nature and lack of narrative drive. It’s not Hamlet. Henry has only a few decisions to make: to judge the veracity of Buckingham’s surveyor, to remove Wolsey for feathering his own nest, to legitimize his attraction for Anne Bullen and to select and protect Cranmer. None of them are particularly difficult.

Unsurprisingly for a play written when the divine right of kings was a hot issue there is little criticism of the king in the text, saving a hint that his interest in Anne Bullen is merely sexual, but for a play regarded by some as a great patriotic celebration there isn’t much praise for Henry either. The play illustrates the trick used by rulers and governments for centuries: pageantry disguises that it’s dangerous at court.

Early performances seem to have used the subtitle All Is True; were you tempted by this strategy and would it make a difference to perceptions about the play?

Doran: I am entirely convinced that the play is called All Is True. Henry Wotton’s letter about the burning down of the Globe says that the King’s Men were performing a play called All Is True, so it seems to me to be the proper title. But it also hints at those rather enigmatic Shakespearean titles like All’s Well That Ends Well, As You Like It, or What You Will. It struck me that the title is a bit like a comedian saying, “this is an absolutely true story”: the more the comedian emphasizes the truth of his tale, the more you question its veracity. I think the title comes with suspicion attached to it, in the same way that All’s Well That Ends Well always seems to me to require a question mark at the end of the title.

We took it a stage further and had in the designer Rob Jones’s set two huge doors, which opened to reveal the Field of the Cloth of Gold at the beginning. When they closed at the end of that piece of pageantry, you saw emblazoned in gold letters across these doors the words “All Is True.” It kept in mind a sense that there was an agenda attached to this dramatization. Was it all true? Can you be true? What is the historical fact? Is there a whitewash job going on? Is this a political gesture to rehabilitate Katherine of Aragon?

One has to remember that Shakespeare had already treated this subject, or at least been part of a collaboration on this very period of history, when he wrote Thomas More. The manuscript of that play suggests it’s in five different hands and it may therefore be that he was only one collaborator of many in that play, but in the reign of Queen Elizabeth that was an extremely subversive subject to discuss, a regular hot potato. In a way Thomas More canonizes the man who had refused the right of Henry to divorce Katherine, and therefore the right of the present Queen—the daughter of Anne Bullen—to reign. To write a play about that and put it on the stage during Elizabeth’s reign was an extraordinary thing to do. Coming back to that same period in history at the end of his career suggests that there was business Shakespeare felt he had left unattended. We blazoned “All Is True” on the walls to suggest to the audience that they had to keep a question mark in their minds.

Thompson: The RSC used Henry VIII, which is a sensible marketing decision as it is how the play is known. All Is True is a great title, though, as one of the driving ideas in the play is that in the court all is true. “All Is true” in the court in the sense that whatever is the current appearance, fashion or policy is taken to be the true and eternal will of the king. Of course, when there is a change in appearance, fashion, or policy then the new situation becomes the true and eternal will of the king. We see Anne shift from lady-in-waiting to heaven-sent queen and then go missing. We know that she becomes the whore that bewitched a king.

When all is true, words cannot be trusted. The members of the court survive and thrive through favor and position as all the power is concentrated in and flows through the king. Words are used to curry favor and maintain position and, as so often with strong government, the first casualty is the truth.

Speaking truth to power is, of course, a Shakespearean theme and the play begs the question: who will speak the truth to the king? The play opens with Norfolk and Buckingham complaining about Wolsey’s ambitious schemes and Norfolk warns Buckingham to be careful about telling Henry the truth. Wolsey sees to it that Buckingham doesn’t live long enough to influence Henry.

It is a rare person who speaks truth to power. Even the Lady who brings news of the birth of Elizabeth initially tells Henry that the baby is a boy. Katherine uses her position as queen to expose Wolsey’s tax gathering and to question the reliability of Buckingham’s surveyor as a witness against Buckingham. Cranmer is the only one who fears nothing that can be said against him when pressed by the king.

In Act 3 Scene 1 Katherine refuses to accept Wolsey’s scheme for a divorce: she holds fast to the truth, particularly the truth that she is lawfully married to Henry. In Act 3 Scene 2 Wolsey’s corruption is exposed and he tells Cromwell to fling away ambition. These two juxtaposed scenes, one where someone holds fast to what she believes to be true and one where someone discards all that is false, were what attracted me to the play.

There are more occurrences (twenty-one) of the word “truth” in Henry VIII than in any other Shakespeare play. (All’s Well That Ends Well has eighteen; Henry IV Part Two has sixteen.) The Chorus immediately muddies the water though:

Hope and belief are not usual signs of truth. The Chorus goes on to make clear that what is being shown has been selected and is a partial view:

… For, gentle hearers, know

To rank our chosen truth with such a show

As fool and fight is, beside forfeiting

Our own brains, and the opinion that we bring

To make that only true we now intend,

Will leave us never an understanding friend.

There has been much criticism of the episodic nature of the plot; was it a problem to find a narrative line or did you detect a more subtle shaping of material in the play in the way it juxtaposes contrasting scenes, moods, and characters?

Doran: I deliberately did not try to solve all the problems of the play before we went into rehearsal, but to see how the play unfurled itself during that process. It inevitably has an episodic quality, but then so does history. To begin with I thought that the potential downfall of Cranmer was one episode too many and felt that I should cut Cranmer from the story. But as we rehearsed and grew to know the play, it seemed to me that it is a learning process for Henry himself: he learns how to trust and who to trust. He trusts Wolsey and then the lords gang up against Wolsey, conspire against him, and bring about his downfall. The lords also conspire against Cranmer, and yet this time Henry, knowing Cranmer to be a good man, gives him his support and his blessing. There is an arc to the story in terms of Henry VIII himself learning how to deal with the people around him. The structure of the play emerged by us allowing it to emerge.

Thompson: The narrative line isn’t obvious and there are some delicious juxtapositions. The theater is all about juxtaposition and this play delivers, including: a celebration followed by an execution; the elevation of a lady-in-waiting followed by the trial of a queen; a man of lies followed by a woman of truth; and the coronation of a new queen followed by the death of an old one.

However, there are always two questions to begin with when directing a play: what kind of play is it? And what’s the story?

Henry VIII is clearly a history play. One might call it a docudrama. It deals with events over twenty or so years in the middle of Henry’s reign from the Field of the Cloth of Gold in 1520 to the birth of Elizabeth in 1533 and Cranmer’s political struggles in 1535.

It shows both the public and private lives of the court and we took a decision to have Henry in various states of dress and undress: from his golden and white state outfits recognizable from the iconography to having him entering court in his hunting dress and struggling with his conscience in his nightgown.

The trickier question with this play is: what’s the story? The first four acts deal with exits: the trial and death of Buckingham, the fall of Wolsey, the divorce and death of Katherine, and the disappearance of Anne Bullen after the coronation. These leavings are balanced with the wooing and elevation of Anne Bullen to Queen of England, the identification, promotion, and protection of Cranmer, the birth of Elizabeth and the prophecy of her great reign and the one who will come after.

Perhaps the real story is in the departures of Buckingham, Wolsey, and Katherine, and the disappearance of Anne Bullen?

We made a great deal of the exits: using the architecture of the church to give Buckingham, Wolsey, and Katherine long walks down the nave to a glorious exit beyond the audience and the crossing to the altar. A countertenor sang an ethereal tune and the lighting was suitably dramatic. A ghostly nightgowned Anne watched the christening of Elizabeth from the altar.

The story of the play might be that the only way out of the Tudor court is by death.

Another way of answering the “what’s the story?” question is to look at the journey of the main character. What happens to Henry VIII? Henry shifts from trusting the ambitious Wolsey who sowed division to trusting the pious Cranmer and ordering the factions to unite behind him. Henry leaves the barren Katherine and ends, by way of the fecund Anne Bullen, holding the new hope Elizabeth. So the kingdom moves from barren corruption to fertile prosperity. Our sympathies, though, are with Wolsey and Katherine.

There is a contemporary political parallel too. Wolsey was a ruthless and powerful political servant who operated as the power of the throne. He is shown in the play to serve his own interests as well as those of the state. The feared Robert Cecil, who had straddled the reigns of both Elizabeth and James, had been seen in some quarters as another Wolsey. Cecil had died in 1612 and Henry VIII was first performed in 1613. After Wolsey’s fall a new man arrives: Cranmer. Cranmer serves both God and the king and is incorruptible. It’s as if Shakespeare is asking, what kind of man do you want in government? Interestingly, James I’s solution to the problem of having so much power in one position was to leave the office of Secretary of State vacant until 1614.

The divisions rift by Henry’s madness were still causing tensions in James’s reign and so the choice of which parts of the story Shakespeare would tell was politically sensitive. The Jacobean audience would have been acutely aware of one absent character. There is just one reference in the play to Mary Tudor. Just before her death, Katherine reveals that she has commended her daughter to Henry and asked for her protection. Henry had only one real job: to provide an heir. Three of his children ruled: Edward, Mary, and Elizabeth. Edward was born after the play ends. Elizabeth is celebrated. Where is Mary? Her absence is part of the story too.

The 1762 Drury Lane production boasted 130 figures in the coronation procession in Act 4, including “The Queen’s herbwoman, strewing flowers” and “six Beef-Eaters”; does that sort of lavish spectacle attract you and how did you create your own coronation procession?

Doran: I tried to set up the glory of the spectacle, which has a theatrical impact, at the same time as saying that the narrative is going to end as everybody knew: in Anne Bullen’s head being chopped off. We tried to place those pieces of spectacle not just as excuses for a lot of nice costumes and some music, but as something that you could see had a political agenda.

Thompson: Spectacle is an important part of theater and I, like many people attracted to theater, love the lavish and we indulged in spectacle where mentioned in the text: fireworks were visible through the west window for the entry of the goat men for example. However, if we had the resources to create the sort of extravaganzas seen in Drury Lane in the eighteenth century I suspect I would have preferred to double the actors’ wages before spending anything on herbwomen strewing flowers or Beef-Eaters for the coronation.

Our coronation procession was about raising Anne as Henry had done. She was pushed down the nave above head height on a wheeled platform. Her eyes were focused on the horizon and her arms outstretched. She was a kind of sacrifice and is not seen again in the play.

The questions I was asking in rehearsal were: what does the spectacle do? What is the coronation scene about in terms of the play as a whole? What does it add to our understanding? Why are the gentlemen discussing who is who and where they are in the procession? Why does one gentleman recognize some people but not all?

I think that with the passage of time we have lost some of the significance. Shakespeare is showing us—or reminding the Jacobean audience—who had influence in the Tudor court after the removal of Katherine of Aragon. The contemporary audience will also have a sense of who was missing from the coronation. The marriage to Anne Bullen split the country. Thomas More’s friends bought him a gown to wear at the coronation. He kept the gown but did not attend. It is akin to the much-commented absence of past Prime Ministers Tony Blair and Gordon Brown from the wedding of Prince William to Kate Middleton. Or the position of the Leader of the Opposition, Ed Miliband, tucked away in the third row, when President Obama addressed Parliament recently. The absences and positions are lost on many but significant for those in the know. I am not sure whether we successfully communicated this or not but I do think that the scene is about more than spectacle and makes a dramatic comment on the rise and fall of members of the court. Again the play hints that the Tudor court was a dangerous place to be.

11. 2006, Gregory Thompson production. Aoife McMahon as Anne Bullen. “Our coronation procession was about raising Anne as Henry had done. She was pushed down the nave above head height on a wheeled platform. Her eyes were focused on the horizon and her arms outstretched. She was a kind of sacrifice and is not seen again in the play.”

Although the play is called Henry VIII, there’s a stage history of Wolsey and Katherine being seen as the leading roles; how did you manage the balance between these three characters in dramatic terms?

Doran: Adrian Noble gave me very good advice in making sure that the casting was the best I could possibly get, and in securing Jane Lapotaire (Katherine), Ian Hogg (Wolsey), and Paul Jesson (Henry) to play those three roles I didn’t have to do that balancing; it sorted itself out. Wolsey is a great starring role. It was one of Irving’s roles and is an amazingly good part even though he disappears halfway through. I think maybe if you put all your eggs into that basket and have a star actor playing Wolsey to the detriment of the other characters, then once he has left the stage the audience is left wondering when he’s going to come back on.

Katherine of Aragon is a wonderful part but I remember Jane Lapotaire describing it, after many performances, as a lonely part. There are four of what we described as “seasonal” scenes. She has her spring, her summer, her great moment in her autumn and then her decline into winter, but she doesn’t spend a lot of the time interacting and that was difficult. But it’s a spectacular role for an older actress.

Thompson: The play does the balancing act. I didn’t want to interfere with the dynamics of the play as written but to bring them out. I thought the best way was to be as physically close to the characters as possible.

Our Henry was as powerful and capricious as we could make him. We wanted to show the man and the monarch and consciously imitated the known portraits and popular images of Henry. Antony Byrne is a powerful, intelligent, and leonine actor with an RSC pedigree and I knew would give us a look of Henry in his prime. The play does not cover Henry’s decline into illness and obesity and so I wanted a younger stronger Henry than has been cast in the past.

Similarly, Anthony O’Donnell is an award-winning actor with a history with the RSC and enjoys the same physical stature as Wolsey. He is a rich comic actor and is more usually considered for lighter roles. I had a hunch that he would capture the tragedy of Wolsey’s loss.

For Katherine, the common choice is for a British actress to play Spanish. I was attracted to the authenticity of hearing a foreigner trying to speak English beautifully. I remembered Corinne Jaber from Peter Brook’s Mahabharata. The sense of the queen as both an insider and outsider in the court, both at home and far from home, was a given as soon as she spoke.

Having made the casting decisions the next step is to set up a framework so that all three characters are as powerful as can be. Actors gain power in the theater by going on a journey so we needed to play the forcefulness of Wolsey where his look could silence even the aristocrats of court and he’s second only to the king; the potency of Katherine as she marches into Henry’s court to fight her case; the vitality of Henry as he never tires but runs from hunting to court to party and dance and then show how Wolsey, the man who has lost all he has strived for, seeks to preserve some dignity; how Katherine’s fierce energy even at her last breath affords her a spiritual awakening; and how Henry despairs of providing an heir and is desperate to find a courtier he can trust and rely on. I believe the balance in dramatic terms is achieved by playing the twists and turns of fortune to the maximum so that the joy is joyous and the tragedy terrible.

Shakespeare is kinder to Henry than history has been—he doesn’t blame or criticize his actions; did you play up the image of him as “bluff King Hal,” Bluebeard in a fatsuit, or did you see him as growing in stature as king in your production?

Doran: Henry is at this stage in his vigorous youth; not the fat old man of the later Holbein image. He has vigor and he grows throughout the role. There are some potentially subversive moments within the play. I learnt a very important lesson: it is possible to over-produce these plays. It tends to be done either by changing scenery between scenes or by putting musical cues between scenes. It’s very common practice but you can miss extra elements of the writing by doing it. You can do the same if you put an interval in the wrong place. At the end of Act 2 Scene 2, just before the first entrance of Anne Bullen, Henry is debating what he’s going to do about Queen Katherine. Finally he says that he must leave her: “O, my lord, / Would it not grieve an able man to leave / So sweet a bedfellow? But, conscience, conscience: / O, ’tis a tender place, and I must leave her.” The end of that scene seems to suggest that Henry VIII is basing his decision to divorce Katherine entirely upon his conscience. The next scene begins with Anne Bullen talking to the Old Lady character: her first line is “Not for that neither: here’s the pang that pinches.” It’s in the middle of a conversation they are already having. If you run the two scenes together, it’s as if Anne is answering the last line of the previous scene, saying it’s nothing to do with conscience—which of course is what many of the people in the audience are thinking. That is a rather subversive thing to do, but it allowed us to keep questioning the “All Is True” nature of the piece, and try to see what the perspective of the writers to the material was: what their attitude was in suggesting to the audience to keep questioning the historical “facts.”

Thompson: I think that it may not be Shakespeare who was being kind to Henry but that our perception of “bluff King Hal” came from the Victorian era and their view of history as the history of great men. No doubt this image was redoubled in the popular imagination of the last century by the gargantuan Henry of Charles Laughton in The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933) stalking the corridors to get to Anne Bullen and even Sid James in Carry on Henry (1971) as “a great guy with his chopper.” We can thank David Starkey and his ilk for our subtler understanding of Henry’s tyranny.

Even in the reign of James I, it would have been dangerous for Shakespeare to portray the tyranny of the late Queen’s father. It was a balancing act for Shakespeare: how to bring true praise to the king and censure the tyranny. It is significant that the play ends before Henry begins the madness of beheading his wives. In the second half of the play Henry is “rescued” by the arrival of Cranmer and Elizabeth. I prefer to think that Shakespeare is being as critical as he could be in the circumstances. The play is saying that the court of Henry VIII is a very dangerous place to be and even now it would be dangerous to present much beyond the birth of Elizabeth.

The part of Katherine is powerfully drawn and immensely sympathetic—Shakespeare strengthens her character notably in relation to the accounts in the chronicle sources he used; how did you capitalize on this?

Doran: The other element that my research threw up was that, in 1613, with a potential Catholic marriage for King James’s son, Prince Henry, on the cards, there was a political agenda to putting on the play in the first place. In the rather Augustan policy that James had of trying to reconcile England with Spain post-Armada, one of the things that a play might do was to tackle the issue of the Spanish Queen, Katherine of Aragon, and what had happened to her. The play virtually canonizes Katherine of Aragon and that seemed to me to be an intensely political gesture.

I read a piece of research by Professor Glynne Wickham that it was possible that the play had been staged at Blackfriars theater (we know the play was also staged at the Globe because it was during a production of it that the Globe burnt down), in which case the scene of Katherine’s trial would have played in the very room in which the trial had actually happened (before it was converted into a theater). That must have been an intensely political act in itself.

Thompson: I’m afraid I didn’t refer to the historical sources in relation to Katherine but directed from the play. The sources are useful when they give you something not in the play rather than when they give you less. You can only play what’s written, of course.