Allow them to give input on training scheduling.

Allow them to give input on training scheduling.As a good coach tackles the challenge of solving each athlete’s training puzzle, he soon learns that every athlete is unique and requires a training program specific to that athlete’s strengths and limitations. Excellent coaches prescribe specific training to fit each athlete. Beyond the individual differences seen between every triathlete, however, good coaches also need to account for the special characteristics found within some triathlete populations—such as beginners, youth, and female or masters athletes. A strong knowledge of how these special athletes may differ from the typical adult male athlete can help a coach avoid potential problems.

Although triathletes from all populations share far more similarities than differences, the coach must still consider each athlete as an individual. This chapter addresses potential differences and similarities between athlete groups and gives training examples of how to help all athletes succeed at their goals.

For a coach, there is nothing quite like guiding a beginner to her first triathlon finish line. A coach of beginners has the privilege to be partner and witness to a truly life-changing event in that new triathlete’s life. It can be every bit as rewarding as the opportunity to coach an elite athlete to a podium finish. It can also be just as challenging.

Triathlon is a thriving, growing sport. In the first nine months of 2011, USAT licensed 57,555 new members and sanctioned 641 new races (out of 2,353) in 2011. A beginner’s training should focus first on development of the skills and endurance necessary to complete the goal event safely and enjoyably. The beginner athlete’s training and racing journey should help him develop a love for the sport and the desire to continue with future competitions.

In short, the keys to success for beginners are as follows:

Allow them to give input on training scheduling.

Allow them to give input on training scheduling.

Give them training sessions that are short and easy enough to ensure completion.

Give them training sessions that are short and easy enough to ensure completion.

Early weeks are mostly about learning how to train, not about building fitness, so be patient.

Early weeks are mostly about learning how to train, not about building fitness, so be patient.

Avoid pace- or time-based goals.

Avoid pace- or time-based goals.

Focus on teaching skills and building the fitness required to safely complete the race.

Focus on teaching skills and building the fitness required to safely complete the race.

Beginners may have never before experienced structured training. Remember, these are independent adults, accustomed to programming their own schedules. They may initially feel uncomfortable at the loss of this control. It is important to communicate often with them about how the training is fitting into their lives. Get their input, and give them back a little control over how the training days and weeks look. Allow your beginning athletes to tell you which times are best for training each day of the week, and give them a chance to update this as often as needed. As a result, you will prescribe training that will fit into their schedules. This will make it more likely that they will complete most of their training and feel confident and positive about it. Realize they will change their minds often as they find out more about how pools, bikes, and running shoes fit into their work and family lives. Take it one week at a time during the early weeks, and remain extremely flexible.

Any coach who has spent recent seasons with veteran triathletes will tend to overestimate how much of a training load to give a beginner. Although an easy training session for a seasoned triathlete might mean an hour swim, bike, or run, a beginner might need to start with extremely short sessions that hardly warrant a shower. For example, a beginner runner might complete only 10 minutes of running in an early-season training session, or a swim for a beginner might mean a lesson with technique focus and only 200 to 300 meters of swimming. Although your beginners may express the enthusiasm to go farther in these initial sessions, make sure to design training sessions they can complete successfully, with the desire to do more on the next day. Start transitioning them into the routine of a triathlete one tiny step at a time. Allow them to spend part of their early training time investigating the pool, learning how to hook a bike up to the trainer, getting a proper bike fit and a comfortable saddle, and acquiring proper clothing and footwear for every session. Err on the side of too little training rather than defeating them right away. Ensure they feel early success as they begin their journey to that first race.

Beginners approach their first triathlon with an overwhelming mixture of emotions. There is a mountain of equipment to acquire and learn how to use. The coach may need to teach swim technique and help the athletes overcome very real swimming fears. The majority of beginner triathletes are tentative or new cyclists, requiring thorough guidance on where and how to ride their (often new) bikes. Coaching these athletes through the run segment means teaching them proper nutrition, hydration, and pacing strategies to maintain their strength through to the finish line. The most important strategy for coaching beginners is to assume they have absolutely no knowledge or experience with any triathlon discipline. Start from zero and provide clear, detailed instructions, and anticipate misunderstandings. This is a time when the two-way communication of a personal coaching session or phone call may address all an athlete’s questions better than an e-mail.

Race results and pace- or time-based goals should be pushed aside because the ultimate goal for beginner athletes is to gain the skills and strength to safely finish the race. A beginner should be focused on crossing the finish line feeling strong rather than on holding a certain speed on the bike or during the run. Examples of good first-race goals include the following: Stay calm during the swim; drink a bottle of water during the bike; hold back to an easy jog for the first mile of the run. The beginner athlete has control over achieving goals such as these and by doing so will have a better race overall.

Beginner triathletes will have successful first races if they have the skills to race safely and the endurance to make it to the finish line. Speed is not nearly as important at the beginner stage of development. Instead, have athletes spend training time practicing how to set up a transition area. They should practice efficient transitions frequently in the weeks leading up to their race. They should learn how to change a flat tire and have basic knowledge to maintain their bikes. Beginners need open-water experience under supervised and safe conditions. You will have to teach them about triathlon-specific clothing and equipment and how to use them. Coaches must help new athletes learn how to drink and fuel before, during, and after training and racing situations. Training sessions should address mental skills, pacing strategies, and the basics of training language and training zones. Coaching a beginner is a wonderful challenge. It is very gratifying for both coach and athlete to cross that first finish line.

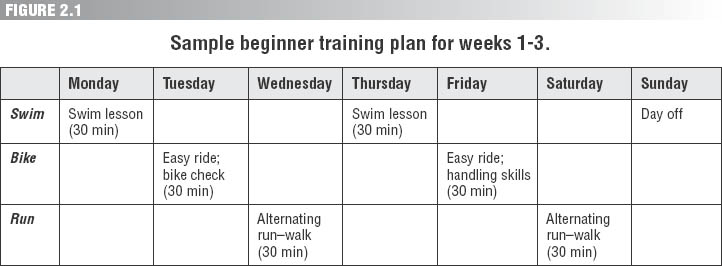

Prescribing training for beginners means designing short workouts at an easy intensity to introduce the new athletes to each mode of training. The first swim workouts should be swim lessons. The first bike workouts should be bike fits and equipment checks. The first run workouts for beginner runners should be run–walk patterns based on their experience and fitness. Total training time for the first several weeks might be six to nine training sessions, each lasting about 30 to 60 minutes, for a total of 3 to 7 hours. A beginner’s first week might be as simple as the weekly plan shown in figure 2.1.

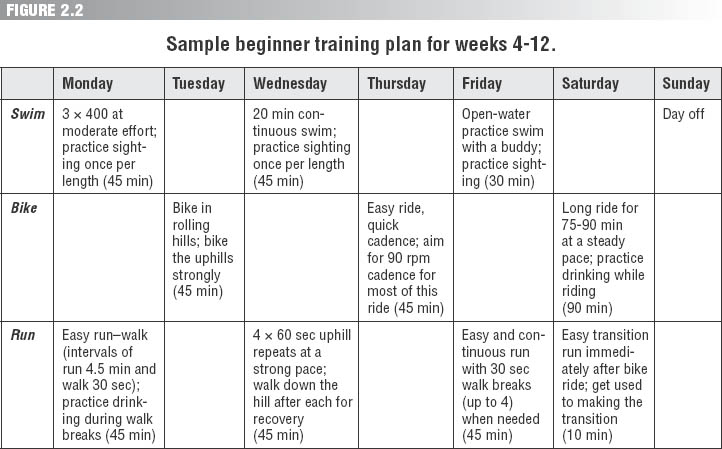

If your beginner athlete gets through these first several weeks, he will have the confidence and excitement to continue and to build from here toward the race distances. After a few weeks, the athlete will be ready to progress to workouts that begin to resemble the race he is training for. These workouts will continue to hone the athlete’s triathlon skills as well as build his ability to endure longer swims, bikes, and runs. In the water, the athlete should work toward the ability to swim the race distance nonstop in the pool and in the open water. If swimming is a weakness for the athlete, the coach should include more frequent swims—maybe four or five swims a week to advance the athlete’s swimming endurance more rapidly. Training should progressively work the athlete up to race distance on the bike. And in run training sessions, the athlete should lengthen his continuous runs as well as practice the run–walk pattern (if necessary) he will use to complete the race distance.

The number of training sessions per week will remain about the same as in the early weeks (six to nine sessions per week). However, the length of many sessions may increase slightly, with most workout sessions being 30 to 90 minutes. Total training time for a typical week will be in the 5- to 10-hour range for most beginners. A beginner’s training plan for these weeks may look like the plan in figure 2.2.

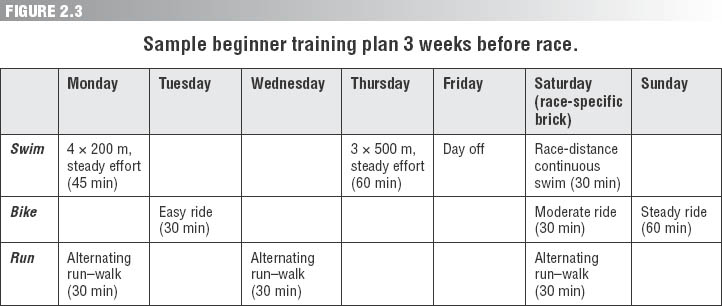

As you move within 3 or 4 weeks of race day (late in the competitive phase of training), the athlete should be able to complete stand-alone swims, bikes, and runs that equal the race distance. The athlete also needs to complete some swim–bike and bike–run “bricks” that come close to race distance. The triathlon term brick means to complete two or more triathlon disciplines within a training session. The athlete might do a race-paced swim followed by a bike training session, with a very short transition in between the two workouts. Bike–run bricks are very important to teach the new athlete what it feels like to run on legs already fatigued from biking. The coach should teach proper race-day nutrition and race pacing and have the athlete practice these during race-simulation bricks. Three weeks before the race, your beginner’s training might look like the weekly plan in figure 2.3.

The last two taper weeks will be for the athlete to rest, practice transitions, gather and tune up equipment, and finish discussions about nutrition and pacing. The coach should plan to spend some extra time on the phone or in person during race week to talk through every step. It is important to help the athlete visualize the good and bad moments of a typical race and how to react appropriately. Finally, be sure she knows you are rooting for her and are proud of her efforts. Then step back and watch the joy on her face when she finishes.

Youth triathlon is a rapidly expanding sport. There were 42,626 youth USAT members in 2011; approximately 29.07 percent of all USAT members are aged 7 to 19. Race directors are providing more kid triathlons, with safe courses and age-appropriate distances for kids as young as early elementary school. Youth triathlon teams are developing across the country, providing opportunities for these young athletes to train together and be part of a coached team. But, remember, young athletes are not simply small-sized adults. There are many differences to consider when creating training sessions for these special triathletes. Note that chapter 24 covers coaching youth athletes in more detail.

Some of the unique considerations when coaching young athletes include, but are not limited to, safety, fear, motor coordination, maturity, attention span, physical reactions to weather conditions, parental fears, growth issues, nutrition, competition with other sports, group dynamics, team building, confidence building, developmental readiness, and basic skills for all three sports plus transitions. A youth coach should not be a beginner coach. This group warrants an experienced coach, knowledgeable in how to properly coach young athletes, who will be present at all training sessions. Any coach willing to take on these youngest, most special triathletes will realize quickly that this group can be the most challenging and most rewarding group of all to guide. After all these considerations, however, the highest priority for coaching young athletes is to nourish a new love for the sport. If a young triathlete loves triathlon, then he will love the practice and learning involved in training. In short, the keys to success for youth are as follows:

Develop skills and speed.

Develop skills and speed.

Ensure safety.

Ensure safety.

Keep training fun.

Keep training fun.

Maintain open communication.

Maintain open communication.

Educate on proper nutrition.

Educate on proper nutrition.

A coach’s first priority with young athletes is to help them develop skills. Practice sessions with elementary and middle school youth should involve skill drills at every session. Running drills to develop proper form, cycling drills to improve bike handling, and swimming drills to develop proper stroke technique should provide the foundation for each practice. Young athletes are physiologically primed to learn skills more rapidly during these years.

Coaches must realize that motor patterns are most easily learned at a young age. Once learned, these motor patterns are stored in the central nervous system. A young athlete who practices and learns speed will develop into a faster older athlete. In addition, youth is the prime time to develop certain types of muscle fibers, especially fast-twitch fibers, and the neuromuscular patterns required to be fast. Therefore, young athletes should spend much of their practice time doing short sprints to develop speed and economy of movement.

Remember, too, that as young athletes grow, their bones grow first, followed eventually by the surrounding soft tissue (muscles and ligaments), which can be weakened and stressed as a result. Coaches should be aware of their athletes’ growth spurts and reduce training stress during those periods. And during growth spurts, the kids, parents, and coaches should expect to see the athletes take a step backward in terms of training and speed. A coach should also recognize and respect that there are early developers and late developers. The coach must take care to not give early developers more attention and recognition. Late developers can often become the most talented athletes with a patient and motivating coach.

Young athletes have a much more difficult time sustaining a strong effort for several minutes than adults because of their low economy of motion, inability to release body heat, and low ability to store and use muscular glycogen. Youth athletes have a lower cardiac output and a lower  O2max than adult athletes. Their heart rates are much higher during rest and during activity. All these things begin to improve as the young athletes reach and surpass puberty, but for preadolescent athletes, adultlike endurance training and adult endurance races are not appropriate. It is important to find age-appropriate race distances and to focus more on fun and short speed than to assign grueling intervals during triathlon practices.

O2max than adult athletes. Their heart rates are much higher during rest and during activity. All these things begin to improve as the young athletes reach and surpass puberty, but for preadolescent athletes, adultlike endurance training and adult endurance races are not appropriate. It is important to find age-appropriate race distances and to focus more on fun and short speed than to assign grueling intervals during triathlon practices.

When training young athletes, the coach must consider every potential safety hazard. Young triathletes should pass a swim screening and swim regularly. Membership in a youth swim team is a great start for the youngest triathletes because it gives kids good instruction in technique, practice at swimming in a racing situation, practice at swimming in a crowded lane, and plenty of training. Even with a swim team background, any swimmer can panic at her first open-water swim. Therefore, open-water swim practices are crucial, and a coach should conduct them regularly in a safety-conscious environment, with lifeguard supervision and enough adults to thoroughly watch and assist each swimmer.

Cycling is the other potentially dangerous sport. Most youth triathletes will eventually crash. Therefore, have a good first aid kit and an emergency plan. Youth must cycle in an area that is completely safe from traffic and free of hilly terrain that is beyond their bike-handling capabilities. If the riders are on a bike trail, the coach will need to teach them how to pass pedestrians politely and safely. When riding in groups, the coach will have to combine riders of similar abilities and consider who may need to ride alone or with more space around them to be safe. Adult riders should ride with each small group of kids. When coaching youth riders, a coach will need to teach each athlete how to brake safely, when and how to shift gears, how to turn corners and make cone turns, how to draft, how to speak to other riders regarding stopping or slowing, and how to properly wear a helmet.

Safe running training for kids just requires a safe course. Make sure the footing is good, and look for a training venue that offers a variety of running surfaces (trails, grass, asphalt, hills). The course should be safe from traffic and easily monitored by the coach. Runners should each pair with one or more buddies for their runs.

A good youth coach will also be ready to modify training for all sorts of weather situations. The coach should have a bad weather plan and be ready to use it at the first sign of lightning. Young athletes do not sweat as efficiently as adults do and are more susceptible to heat-related illness. Conversely, young athletes are also more susceptible to hypothermia. The coach needs to teach athletes how to adjust to weather conditions with proper hydration and clothing choices.

A good youth coach will incorporate games and fun challenges in every practice session. Games are the best way to increase the amount of high-quality running in a practice. Games strengthen teams, help with short attention spans, develop speed and agility skills, and help nurture that love for triathlon that is so important for the development of a great young triathlete.

Contests and practice races are good ways to motivate young triathletes. For example, put up a map of the United States, and tally team weekly running miles to “cross the country”; have a weekly race or time trial, with a frozen fruit bar for all finishers; pick an athlete of the week, and reward him with a small prize; or give each kid a nickname that matches her personality and conveys strength, skill, or speed. And above all, a good coach will hammer the theme of team. Team games, team colors, team songs, and team cheers all remind these athletes they are training and racing for their team as well as for themselves.

Communication is critical for a good working relationship between coach, athlete, and parents. The coach should communicate to athletes and their parents by phone or by e-mail at least weekly about upcoming training sessions, racing schedules, and any other group concerns. The coach who sends personalized e-mails to each athlete regarding individual goals and accomplishments will make all the athletes feel special and involved in their growth as triathletes.

Coaches should educate youth on how to properly fuel their training and racing. Without good nutrition, all the training will go to waste, and the youth athletes can suffer health problems. A good coach will teach kids the information they need in order to choose energy-packed, healthful foods that will give them strength and health. The youngest competitors and their parents may not understand the importance of hydration and food before, during, and after workouts. Kids tend to choose foods based on taste, appearance, and availability, so teaching them to plan their breakfasts and pack healthy snacks is important. Kids do not have a sensitive thirst signal to tell them to drink. Hydration education is crucial. The coach can hand out clear water bottles marked in two-ounce (60 ml) increments to help kids learn the concept of hydration volume and practice drinking regularly.

Nutrition coaching becomes even more complex when athletes begin to go through adolescence. Female athletes will naturally grow and gain body fat during adolescence, and each girl may become very conscious of her new curves and the loss of running speed due to weight gain. The coach needs to emphasize that this is normal and help guide the athletes through this period with a base of how to properly stay fueled. Boys may go through a similar stage where they gain weight before they grow taller. One insensitive comment by the coach about “getting big” or “needing to lose weight” can send a kid spiraling toward a long-term eating disorder. The coach, as a respected authority figure, can make a positive difference during this awkward time with good information and advice.

Early-season workouts (preparatory phase) should introduce a training routine that will remain consistent throughout the season. Training sessions should start on time but with a “sponge” activity that allows latecomers (usually not the young athletes’ fault) to join practice without disruption. Functional dynamic warm-up and stretching routines are good for the first 10 to 15 minutes of practice. After the team learns the routine, the older athletes can take turns leading the warm-up while the coach says hello to each athlete and explains the workout for the day.

Early in the season, training should be preparatory by starting easy and progressing according to the child’s abilities and skills. It is better to be too conservative with training than to risk burnout or injury with these new athletes. Coaches should make sure their young athletes are recovering well and remaining positive about going to practice. If not, these are sure signs that training should be reduced for more rest.

A youth coach must remember that kids can build fitness very quickly. The coach can save the toughest workouts for the competitive season and spend the early, precompetitive months building skills, safe habits, speed, strength, and confidence in the athletes. Appropriate weekly training hours range from 4 to 8.5 hours of training for athletes 12 and under, and up to 16 hours for athletes older than 12. Young athletes should spend about half of their training time swimming, as swimming skills require much practice, and the nonimpact nature of swimming is the best place to build endurance. Typical swim team workouts are usually age appropriate and excellent for young triathletes.

Young triathletes should frequently practice bricks that come close to their race distance, allowing them to complete two or more triathlon disciplines within a training session. This gives them a chance to practice the skill of transitioning from swim to bike and then from bike to run. In addition, skills such as getting shoes and helmets on and mounting and dismounting a bike can be difficult for young athletes, so transition practice helps them gain valuable experience. And finally, even the youngest triathletes need some strength training. However, it should come in the form of exercises that help the young athletes move their own body weight with good strength and balance. Dynamic warm-up running exercises, jump rope, simple plyometrics such as hopping and skipping, and hill repeats are all good strength-building practices.

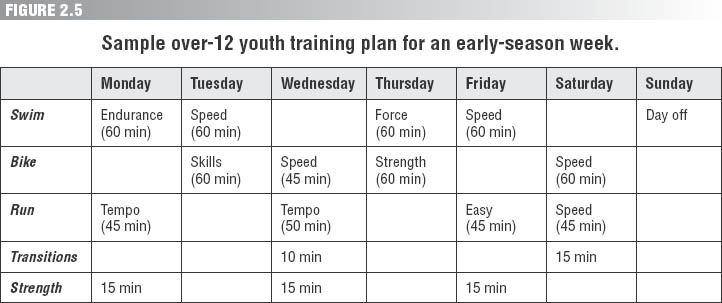

An early-season training week for youth age 12 and under gives them an opportunity to swim, bike, run, practice transitions, and build strength three times each per week. The week may look like the plan in figure 2.4, whereas an early-season training week for athletes over 12 may look more like the plan in figure 2.5. As young triathletes transition into over-12 training, be patient because some of the younger members of this age group may still do better with the lighter 12-and-under schedule. The triathletes who are ready can handle four sessions of swim, bike, and run each week, with three functional strength sessions per week and short transition practices as needed.

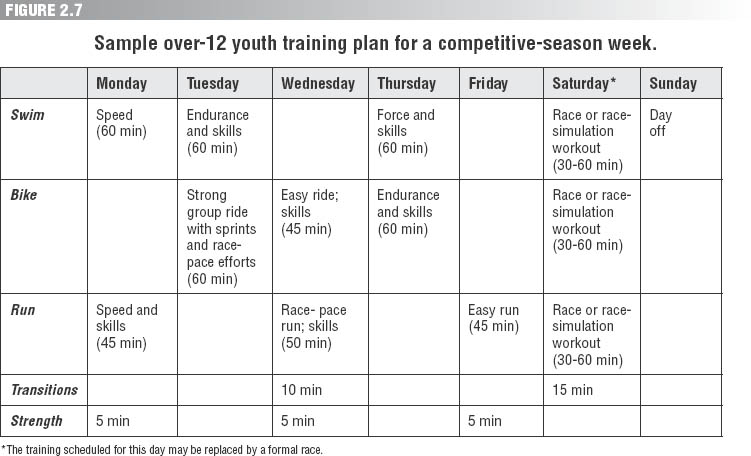

During the competitive phase, the athletes should perform two or three race-specific workouts per week. Race-specific workouts give the athletes a chance to practice race pace and race distances in practice. In these workouts, the coach should frequently pace the athletes at race-goal pace. Races may be substituted occasionally for such workouts, but be careful not to race too often (racing is mentally and physically draining). Overall training volume should decrease during the competitive season to allow extra rest and recovery from these important workouts.

A competitive-phase training week for youth 12 and under will have easier midweek practices to allow recovery for the weekend races or race-simulation practices, as shown in figure 2.6. A competitive training week for triathletes older than 12 is built on the same philosophy of harder races or race simulations followed by easier practices and opportunities for recovery, as shown in figure 2.7.

For the purposes of this book, these training week examples are very general. In reality, the coach will need to adapt training to each athlete’s skills and weaknesses and carefully monitor the energy level of each athlete. The coach should promote balance between school, family, fun, and training. A happy athlete is a strong athlete.

In triathlon, a masters athlete is one who is aged 40 or older. As of the end of 2011, 39 percent of USAT annual members met this criterion. In fact, the largest single age group for both female and male USAT annual members is the 40 to 44 age group. Masters athletes may have more time and disposable income for racing than their younger counterparts. However, it doesn’t matter how hard we try to stay young, as we grow older there are certain undeniable physiological changes in our bodies. The good news is that proper training can delay or diminish these changes.

A masters athlete’s training focus should be on the quality of each training session combined with the opportunity to recover and rest adequately before the next session. Masters athletes should spend less time doing long, slow endurance workouts and more time preserving their speed with harder training and racing efforts. Triathletes 40 and older often have extensive racing and training experience, and they can use this knowledge to race and train more successfully.

Coaches can ask masters to talk through past races to find out what went well and to learn from mistakes. Masters athletes may also have the maturity to approach training and racing in the most healthy and balanced manner, and they may have more time and money to devote to their racing passions. These advantages mean that some endurance masters athletes can still set new personal bests well into their 50s. In short, the keys to success for masters are as follows:

Strength train regularly.

Strength train regularly.

Plan adequate recovery.

Plan adequate recovery.

Be aware of the injury potential.

Be aware of the injury potential.

Sometime in our late 20s, all adults begin to lose muscle. This yearly degenerative loss of .5 to 1 percent of skeletal muscle is called sarcopenia. Fortunately, exercise and strength training have been shown to slow the rate of degeneration (Taaffe 2006). This is crucial information for designing proper training for this special group of athletes. Masters athletes should regularly incorporate strength training into their training programs. Two or three strength sessions per week will help a masters athlete maintain strength, balance, and speed.

Masters athletes require more recovery time from training sessions. Athletes 40 and older need more rest days and rest weeks built into their training plans. Where 30-year-old athletes might be able to build their training for 3 weeks in a row before needing a rest week, masters athletes might need a rest week as early as after 1 week of training. Because of this increased need for recovery, masters athletes should cut running days (because of their high impact) down to a minimum—often to just 3 days a week to allow for the balance of adaptation and recovery.

By the time an athlete has reached her 40s, she has probably experienced a wide range of injuries from training and racing. Some of these injuries may become chronic as the athlete ages through degeneration or long-term weakness. The coach needs to prescribe weekly strength and stretching training sessions derived from rehabilitation experts to address muscular imbalances and tightness. The coach must also optimize training volume to allow the masters athlete enough rest for adequate recovery between hard training sessions. Masters athletes generally do best on a lower training volume, with a higher percentage of time spent doing high-intensity or force and strength work.

There is also good news about masters and injury potential. Masters athletes are more likely to be wise about injuries. They have experienced enough of them to know when to stop a training session, take a rest day, or slow down the pace of a workout to avoid injury. If they become injured, they are more likely to know how to heal and have a pool of trusted resources to consult. Many masters remain more injury free in their older years than when younger.

Masters often have a large base of cumulative years of endurance training. They have adapted physiologically from all the years of steady biking, swimming, and running and have built their base. Therefore, they may need less base-building time than younger or less experienced athletes.

If an athlete wants to keep his ability to race strongly at shorter distances, he must continue to do high-intensity workouts and races. The biggest contributor to age-related loss of performance may be loss of aerobic capacity ( O2max) along with loss of speed and power at lactate threshold. Although there is not much available research on the topic, it appears that masters athletes can maintain their aerobic capacity, lactate threshold capacity, and economy until sometime in their 50s if they continue with focused training and racing at a high level (Trappe et al. 1996).

O2max) along with loss of speed and power at lactate threshold. Although there is not much available research on the topic, it appears that masters athletes can maintain their aerobic capacity, lactate threshold capacity, and economy until sometime in their 50s if they continue with focused training and racing at a high level (Trappe et al. 1996).

One study that followed 27 elite endurance athletes over 15 years found that the most active athletes (those who raced shorter races regularly) managed to maintain or even improve their aerobic capacities over the 15 years (Marti and Howald 1990). Conversely, recreational athletes tended to lose aerobic capacity at an average rate of 1 percent per year. Those that became sedentary lost 1.6 percent of their aerobic capacity per year. It appears that frequent race-paced efforts (anaerobic threshold) in training and races help sustain aerobic capacity as we age. Another study tracked the decreasing performance of top triathletes in older age groups at the Triathlon World Championships in 2006 and 2007 (Lepers et al. 2010). Of the three sports, cycling showed the least amount of decline as the age groups became older. Swimming was next, and running showed the greatest performance decline. But the most interesting finding was that the short-course athletes showed the least decline in aerobic capacity, or  O2max. Ironman-distance athletes showed the greatest declines. This finding seems to indicate that masters athletes must include high-intensity training and short-course racing in their regimes to fight off the natural decrease in aerobic capacity that comes with age.

O2max. Ironman-distance athletes showed the greatest declines. This finding seems to indicate that masters athletes must include high-intensity training and short-course racing in their regimes to fight off the natural decrease in aerobic capacity that comes with age.

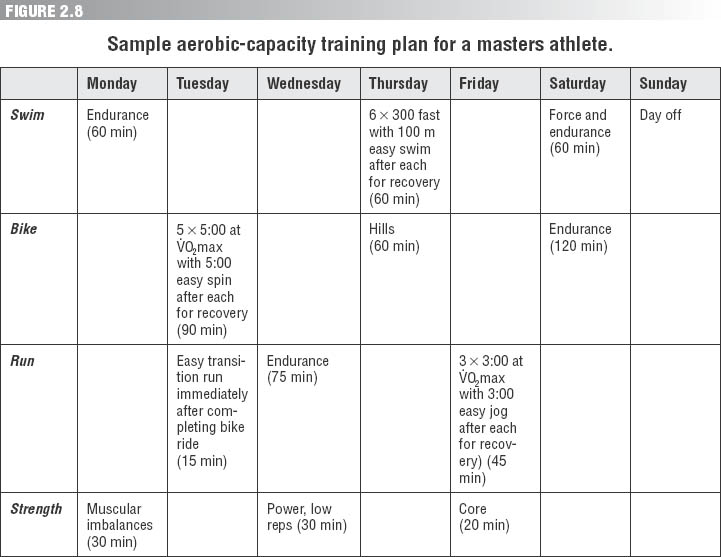

An example of masters-specific high-intensity training is starting with a 1- to 3-month series of intervals done at lactate threshold or just below, building the total interval time per workout up to 20 to 40 minutes. For example, an early interval session might be 3 × 3:00 at 1-hour race pace. Each week the intervals would increase in volume. An example of a late interval session would be 4 × 10:00 at 1-hour race pace. These intervals could be translated to swim, bike, or run workouts—one for each discipline each week. If the masters athlete completes these with no trouble, she is ready for a series of aerobic-capacity intervals ( O2max). Figure 2.8 shows a sample week of aerobic-capacity training for the late competitive phase of training, along with strength training workouts. After this aerobic capacity and strength phase, the athlete should do more and more race-simulation workouts, building toward race distances. For example, the masters athlete might do a 1-hour bike ride with intervals done at goal pace followed by a quick transition to a run done at goal pace.

O2max). Figure 2.8 shows a sample week of aerobic-capacity training for the late competitive phase of training, along with strength training workouts. After this aerobic capacity and strength phase, the athlete should do more and more race-simulation workouts, building toward race distances. For example, the masters athlete might do a 1-hour bike ride with intervals done at goal pace followed by a quick transition to a run done at goal pace.

Athletes are capable of achieving their best race performances after the age of 40. Training needs to address the maintenance of strength and speed rather than involve nothing but easy endurance efforts. Masters athletes can use their experience to make the most of their training journey. A successful training plan will result in healthy, strong athletes who maintain performance or lessen declines well into their 50s.

As of 2011, 38.46 percent of all USAT annual members were female (56,404 women). Talk to most experienced coaches and they will tell you there are few characteristics associated uniquely with one gender or the other (aside from pregnancy and associated issues), so there really isn’t such a thing as a “female athlete” training plan. Rather, coaches should look at athletes individually, considering their strengths, weaknesses, and goals—not gender—when guiding them. However, there are some basic physiological, nutrition, and medical gender differences that coaches must consider when training females. Female athletes approach training and racing with different mental skills as well.

Women have less muscle mass than most men. Female athletes must perform regular strength training to help slow the loss of muscle mass as they age to preserve that smaller initial amount of muscle. Exercises that stabilize the pelvis, shoulders, knees, and core are very important for women because they address the effects of the wider hips and larger hip–knee angles of the average woman’s body. Women who have the strength to keep their joints stable during running are much less susceptible to injury. Stable joints also lead to more efficient running, cycling, and swimming.

In addition, female athletes need access to a qualified bike-fit specialist. Women sometimes do not fit well on bikes designed with the male torso and leg lengths in mind. Bike manufacturers are beginning to realize this and offer bikes designed for women; a good bike fit is the most important component of optimizing rider performance.

All endurance athletes are susceptible to running a calorie deficit during high-volume or high-intensity training blocks. All athletes may be susceptible to disordered eating, although it is arguably far more prevalent in the female athlete. Both disordered eating and accidentally inadequate nutrition in women can lead to the female athlete triad, a gender-unique medical issue that can have serious health implications. The triad begins with inadequate nutrition, disordered eating, or both and progresses to amenorrhea (the absence of menstruation) and then osteoporosis. These are difficult issues to address as a coach. Female athletes may not be honest about these highly personal topics with a coach. When they are, most coaches are not qualified to fully address them. This is an appropriate time to refer these athletes to an expert you trust, then work as a team with that expert to coordinate training with nutrition goals. Of course, coaches should never promote thinness as a training objective. Instead, coaches should give athletes solid, general, proven advice on how to fuel their training and racing.

Female runners tend to be more susceptible to training injuries. Commonly documented reasons for this include the structure of a woman’s body, with its wider pelvis and therefore greater angle from the knee up to the pelvis area. This can lead to increased patellofemoral injuries and iliotibial band syndrome. Females also tend to have loose ligaments—possibly due to the impact of estrogen. Loose ligaments mean hypermobile joints that are not as well supported by soft tissue connections. This can also result in a higher chance of injuries. Most of these injuries can be resolved and prevented with specific strength training targeted at strengthening the weaker muscles that stabilize the hip and the knee.

Women are more susceptible to stress fractures and anemia than are men. Remind all athletes to consume a diet rich in calcium, iron, and vitamin D, and urge female athletes to be checked for signs of anemia with annual blood tests. Supplement with iron only when under medical supervision, as it can be harmful in excess. Stress fractures are often a result of inadequate nutrition or the female athlete triad.

If a female athlete becomes pregnant, she should defer to her doctor for guidance on how it will affect her activity. Pregnancy affects every athlete differently. Some women are able to run, bike, and swim until near the end of their pregnancies with a physician’s guidance. Others find they really need to back off from training for much of their pregnancies. Every woman should consider the safety of each activity done while pregnant as well as how the activity contributes to her and her baby’s health and well-being.

“I’ve found that women are much better at following the race plan—sometimes too good. Even if they have what it takes to go faster on race day, they will often hold back and follow their plan,” says Joe Friel, coach and author of many books on endurance training. “Men, on the other hand, start with the notion they are going to ‘beat’ the plan.” So, good coaching may mean convincing female athletes to take justified risks when warranted. Assign them to take a specific risk in a C or a B race. (For example, have them push harder than normal for the bike segment to see how it affects the run. Convince them that learning is the goal for this race, not overall time. Give them permission to fail when taking a calculated risk.)

When coaching a woman, also consider her background and experiences as a female athlete. Has she had opportunities as an athlete, or were there times when she was not supported in her sporting endeavors? Many women were never brought up to think of themselves as athletes. Sometimes, a coach’s main objective with these women is to get them to that point—to where they dare to describe themselves as “an athlete.” Once there, the possibilities are endless. But until then, how can a woman race to her potential if she does not yet have that fundamental belief that she belongs in the race?

In addition, female athletes frequently struggle to balance work, family, and training—as do male athletes. Without balance, a female athlete will never reach her potential. Coaches should plan rest days, vacations, big work weeks, and time for children and spouses into all athletes’ days, weeks, seasons, and annual training plans. An athlete’s career should revolve around having no regrets. When she is retired from racing and is reminiscing about this part of her life, what will seem important after all those years? Time with loved ones; full involvement with her children; energy spent on other activities that provide emotional, spiritual, and social balance in her life—these should all be good memories along with the memories of training and racing well.

Every triathlete is a unique person with unique skills, weaknesses, schedules, energy levels, goals, and life circumstances. A good coach will understand each athlete and prescribe the training that will help him reach his potential.