Sage Rountree

As yoga grows more and more accessible to Western athletes, more and more people are using it as an important part of training. Yoga’s benefits include increased strength, flexibility, and focus, on both physical and mental levels. Although the physical practice of yoga is the entry point for most practitioners, the system of yoga includes other practices, such as meditation and breath exercises, that directly benefit athletes. For a primer on yoga philosophy as it applies to endurance sports training and racing, please see my book The Athlete’s Guide to Yoga: An Integrated Approach to Strength, Flexibility, and Focus (2008).

Benefits of Yoga

Yoga works to bring your system into balance, and this balance plays out along many lines. On the physical level, yoga can hone your sense of balance, keeping you upright if your bike wavers or you misstep while running. It can also keep balance between opposing muscle groups, by working to strengthen the weaker muscles and to stretch the tighter ones. This muscular balance is critical for the prevention of overuse injuries, which occur when the system is out of balance, either because the physical demands placed on the system were too strong to be balanced with the recovery allotted, or because one group of muscles was stronger or tighter than another.

Yoga also confers a sense of balance between the body and mind, as a yoga practice gives athletes the space to see how their bodies and minds relate, specifically how they interact with the breath. As both an involuntary and a voluntary process, the breath powerfully connects the needs of the physical body (oxygen in, carbon dioxide out) and the abilities of the mind (deep breathing is relaxing; we can control the breath to accommodate various paces in the swim, bike, and run). When we tune in to the breath, we can see what the state of the body is and begin to learn what we need. Sometimes, that answer is more work; often, that answer is more rest. This self-awareness is an important part of training. Athletes often cleave to a set training plan even when it is not working for them, to the detriment of their recovery and therefore to their performance in workouts and races.

Types of Yoga

Whether you are practicing yoga in a class setting or on your own at home, you’ll need to be sure your practice is complementing your training rather than simply acting as an extension of it. You’re probably putting a lot of care into the work you do swimming, cycling, and running. Be careful that your yoga practice doesn’t sabotage your training but instead supports it. That means choosing classes wisely and modifying where necessary. Although the general fitness-minded yoga student might come to class for a workout, the athlete in training has different needs: a chance to relax and recover from the work of training, and to shore up weak areas in the body that have not been addressed in the weight room or in physical therapy. Sweating and pushing the limits may not serve the season’s or week’s goals, so be careful not to be swept into a more-is-more mentality.

When choosing a class or a sequence for home practice, check that your yoga is periodized in inverse proportion to the intensity of your training. That is, when your training is less intense and easier, during the transition and preparatory phases, you can include a more vigorous, strength-building practice. In fact, at this time of the year, yoga might be a direct complement to or even a replacement for a strength workout. As you begin to build toward your key races, though, the intensity of the practice should lighten. During this time, you’ll focus on maintaining flexibility and recovering between your key workouts. And as you reach your physical peak in the competition phase, the intensity of your yoga practice must be lighter still. This is a good time to take restorative yoga classes or to focus on focus itself by practicing breath exercises and meditation. These will bolster the work of mental training in preparation for your race.

Here is some advice on ways to choose the classes and home practice that will best support your triathlon and life goals. Remember that yoga is not a competitive sport; use it as time to balance the work of doing and to rest in simply being.

Yoga Classes

Classes are the best place to learn yoga, as you will have a teacher’s feedback about your alignment and you’ll be far from the distractions of home. Even small towns these days have yoga studios, and there is good yoga to be found at gyms, too. There is no universal system for labeling and describing classes, so you’ll need to keep room for trial and error as you find the right class for you. As an athlete, you are looking for a class that complements your training. This means that although you might enjoy a warm, vigorous, flowing class during your off-season, you’ll need to dial back this practice as you get closer to your peak races. For competitive athletes, it can be tough to control the intensity and hold back in class, even when it’s the best idea. A competitive athlete often believes any options offered to increase the work or stretch in a pose must be tried, but this is not the best approach, as it can lead to overstretching or interfere with recovery.

Following is a list of terms you’ll see on a typical studio schedule:

anusara—An alignment-oriented approach developed by American John Friend, anusara focuses on “heart openers,” specifically back bends, which in their more gentle forms are of good use to athletes, especially triathletes who spend hours each week riding in aerobars or sitting at desks.

anusara—An alignment-oriented approach developed by American John Friend, anusara focuses on “heart openers,” specifically back bends, which in their more gentle forms are of good use to athletes, especially triathletes who spend hours each week riding in aerobars or sitting at desks.

ashtanga—Usually taught in primary-series or mysore (uncued) classes, this rigorous approach takes athletes through a set sequence of poses linked by vinyasa, or flowing movements. Because it is a power-based practice, ashtanga is best kept for the off-season or for the seasoned yogi.

ashtanga—Usually taught in primary-series or mysore (uncued) classes, this rigorous approach takes athletes through a set sequence of poses linked by vinyasa, or flowing movements. Because it is a power-based practice, ashtanga is best kept for the off-season or for the seasoned yogi.

bikram—A franchised style of hot yoga, this style includes 26 specific poses in a room heated to more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius).

bikram—A franchised style of hot yoga, this style includes 26 specific poses in a room heated to more than 100 degrees Fahrenheit (38 degrees Celsius).

hatha—Although this term once meant any physical practice of yoga asana, or poses, it now connotes a slower-paced class with poses held static.

hatha—Although this term once meant any physical practice of yoga asana, or poses, it now connotes a slower-paced class with poses held static.

Iyengar—Classes emphasize precise alignment, using props to accommodate each practitioner. Certified Iyengar teachers have detailed knowledge of anatomy and can be an important resource for athletes.

Iyengar—Classes emphasize precise alignment, using props to accommodate each practitioner. Certified Iyengar teachers have detailed knowledge of anatomy and can be an important resource for athletes.

restorative—A gentle, prop-supported practice concerned less with stretching than with helping the nervous system relax. This is a great choice for a rest day or for the competitive period of training.

restorative—A gentle, prop-supported practice concerned less with stretching than with helping the nervous system relax. This is a great choice for a rest day or for the competitive period of training.

vinyasa—Often associated with flow and power, vinyasa involves moving dynamically through a sequence of poses, often in conjunction with the breath. Depending on the teacher and the level, this will be a faster-paced class and is often best kept for the transition and preparatory periods or for those with more experience mixing yoga and training.

vinyasa—Often associated with flow and power, vinyasa involves moving dynamically through a sequence of poses, often in conjunction with the breath. Depending on the teacher and the level, this will be a faster-paced class and is often best kept for the transition and preparatory periods or for those with more experience mixing yoga and training.

Hot Yoga

Hot Yoga

Depending on your geographic region, you might find that some or virtually all of the yoga available to you is “hot yoga,” practiced in a heated room. Fans of hot yoga love the intensity of the heat and its challenge, and they argue that the heat cultivates flexibility. For an athlete in serious training, hot yoga creates some concerns, and it should be approached with caution.

If you choose to practice hot yoga, pay special attention to your hydration before, during, and after class. Many athletes exist in a dehydrated state to begin with; adding heat can only exacerbate this condition. Beware also of a false sense of suppleness. In the heat, you may find yourself pushing into stretches that are actually too far past your natural range of motion. Take care, lest you injure yourself.

Finally—and this is good advice for any class—trust your own body. The language of some hot yoga classes is extreme, exhorting you to push, to do more, to go beyond your flexibility. Don’t. Set your intention to practice safely, to leave out things that seem inappropriate for your body and your stage in the training cycle. Then stay aligned with that intention.

Home Practice

Your home practice is an integral part of your training, and being regular in your home practice will have a direct positive effect on your performance in triathlon, just as being regular with other elements of your training does. Home practice gives you the time to personalize your practice, shore up your weaknesses, and get to know your body. Consistency is key to seeing benefits. Your home practice can consist of a 5-minute routine or a 50-minute routine. Over time, you’ll see what works for you and what addresses your needs. Be sure you try poses, meditations, and breath exercises that are difficult for you instead of playing only to your strengths. By addressing your weaknesses in home practice, you’ll become a more well-rounded athlete and person.

If you feel adrift when you begin a home practice, there are many resources available. The poses described in this chapter can be a starting point, as can DVDs and online classes. (My weekly yoga for athletes class is available to stream online at YogaVibes.com, for example.) Books can help, too; my book The Athlete’s Pocket Guide to Yoga (2009) is spiral-bound to lie flat and contains 50 routines of specific use to endurance athletes.

Just as you need to take care in class, you should be aware of your appropriate edge during home practice, too. Pay attention to your breath, and let it be your guide. A choppy breath or an impulse to hold your breath is a sign of pushing too far.

Yoga Poses

This section includes some poses you’ll see in class and can use in your home practice, with brief explanations of why and how to practice them. These poses can be practiced on their own or combined to create a full-body routine appropriate for practice after a training session in the base and build periods (and, in lighter expression, during the peak). For specific sequence ideas, please see my book The Athlete’s Pocket Guide to Yoga or my online classes at YogaVibes.com.

Mountain

The base of all other yoga poses, mountain also promotes ideal alignment for balance in the water and on the road. Learn the pose well, and check your form in the mirror and by asking your teacher for feedback. During your practice and during your training, periodically come back to your best mountain-pose alignment, and you’ll find ways to get more efficient and economical in your energy use, thus increasing your endurance.

To take mountain pose (see figure 3.1), stand tall with your feet under your hips. This will probably place your feet about a fist’s width apart, where they would land relative to your hips if you were running. Your hip points, knees, and feet should line up perpendicular to the ground. Balance your pelvis in a neutral position, eliminating any tilt forward or backward. Let your spine grow long, relax your shoulders, and drop your chin slightly. You should feel steady and strong.

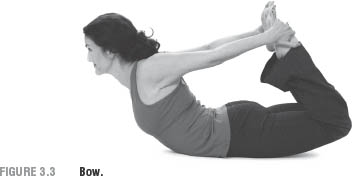

Back Bends

Back bends open the front of the body, which grows tight as we sit in car seats, at desks, and on our bikes, and at the same time they strengthen the back muscles that are overstretched as we hunch forward. Back bends done from a prone position (on the belly) emphasize the strengthening element of the motion and are a necessary precursor to other, deeper back bends.

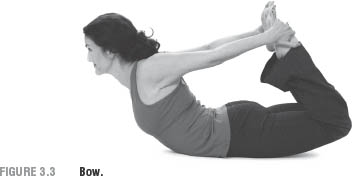

For locust pose (see figure 3.2), rest on your belly and take mountain-pose alignment, holding your pelvis in a neutral position to protect the lower back. On an inhalation, lift your legs straight back behind you, and use your back muscles to pull your upper body off the ground. Hands can be alongside your hips, hover under your shoulders, or reach out along the floor overhead. Hold your shoulder blades down low on your back as you breathe. For bow pose (see figure 3.3), rest on your belly and reach your hands for your feet or ankles. On an inhalation, kick your feet into your hands, and lift up into a back bend. Your pelvis stays down and neutrally aligned; your chest lifts off the floor. Hold your neck relaxed as you breathe here.

Planks

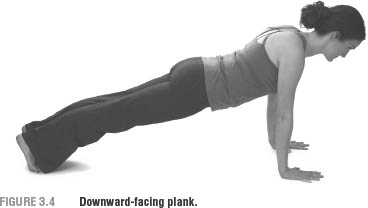

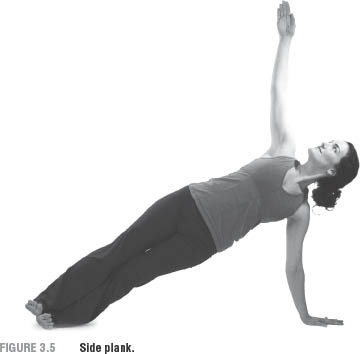

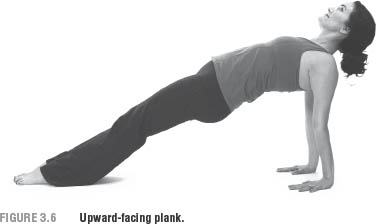

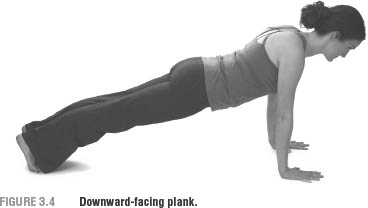

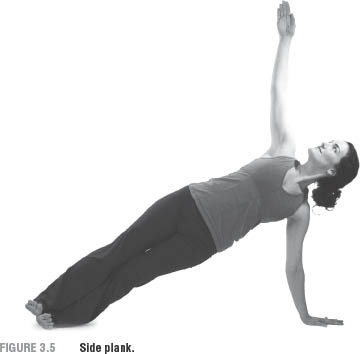

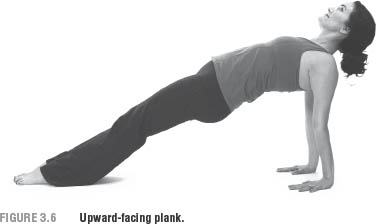

The plank position cultivates core strength by challenging the body to maintain mountain-pose alignment in a different relationship to gravity. Planks can be done on the hands or the forearms, in downward-facing, side-facing, and even upward-facing positions.

For the downward-facing plank (see figure 3.4), position your hands or your elbows under your shoulders, the balls of the feet on the floor, and assume mountain-pose alignment all along the body. Don’t let your hips sag, and don’t lift your shoulders too high.

For side plank (see figure 3.5), rotate to one side, flexing your feet. You can have the foot of the top leg in front of the bottom leg, stacked on top of it, or placed on the ground in front of or behind the bottom leg’s knee. This can be done on the palm or, for greater shoulder stabilization, on the elbow and forearm.

For upward-facing plank (see figure 3.6), position the hands under the shoulders, fingertips facing forward and belly up, and lift the hips off the ground. For less intensity, keep your knees bent; for more, work to straighten the legs and reach your toes to the floor.

Lunges

The lunge balances the musculature of the hips. Longer holds increase flexibility in the hip flexors and hamstrings, while moving into and out of a lunge strengthens the glutes and hip stabilizers while increasing balance.

Do a split-stance lunge with your legs. Check that the knee of the front leg is directly over the foot so that the shin is perpendicular to the ground. You can be on the ball of the back-leg foot (see figure 3.7), or you can lower that back knee to the ground. Hands can be on the floor, on the knee, or overhead. Hips and shoulders are squared forward.

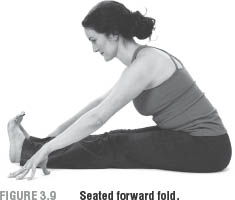

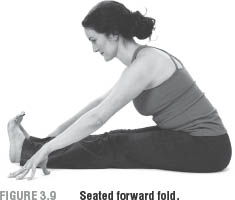

Forward Folds

Forward folds stretch the back of the body, from the calves and hamstrings to the muscles of the back and neck. They make a nice complement and counterpose to back bends.

In all forward folds, the action should begin from the pelvis, which must tilt forward so that the fold isn’t taken too deeply into the lumbar spine of the lower back. Whether you are in a standing forward fold (see figure 3.8) or a seated forward fold (see figure 3.9), you should feel your hip points moving forward into the pose instead of simply bending forward from the waistline. If forward folds feel intense, bend your knees to protect your hamstrings.

Twists

Twists wring out the spine, maintaining rotational range of motion and stretching the chest and hips, which frame the top and bottom of the spinal column. When practiced until they feel even, twists bring balance to bodies that are more comfortable rotating in one direction than the other, which makes triathlon-specific actions such as bilateral breathing in swimming more easy.

A reclining twist (see figure 3.10) is a gentle, pleasant way to stretch the hips, spine, and chest. Lying on your back, bend your knees and drop them to one side. For more intensity, keep the legs stacked and active as you hold your shoulders level against the ground. For less, let your legs relax. You can slide them away from your shoulders. Variations include straightening the bottom leg and keeping only the top leg bent at the knee, or wrapping the top-leg knee around the bottom-leg knee.

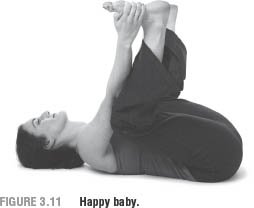

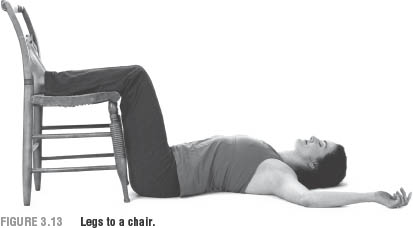

Inversions

Inversions change the body’s relationship with gravity, inviting a new perspective and helping calm the nervous system. Additionally, they help drain excess fluids from the legs, useful for recovery.

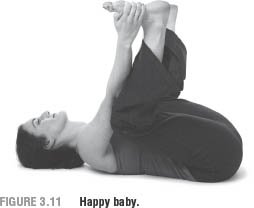

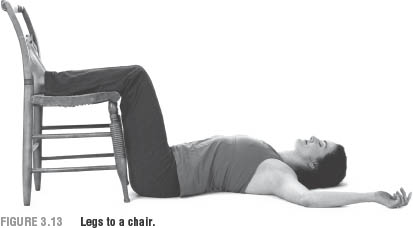

Inversions such as headstand and shoulder stand are best learned under the supervision of an experienced teacher, as they can put undue stress on the neck if practiced incorrectly. A safe alternative is happy baby pose (see figure 3.11), an upside-down squat. Resting on your back, take your knees wide and lower them toward your armpits as you hold your hamstrings, calves, ankles, or feet with your hands. Your tailbone and head should both stay down on the ground. A deeper but also safe inversion is taking a position with your legs up the wall (see figure 3.12) or your calves resting on a chair, seat cushion, or coffee table (see figure 3.13). In either, move toward the prop until your knees are over your hips, and take a comfortable arm position to encourage a gentle release across the chest.

Resting

Rest is where the gains of exercise occur, as the body repairs itself and supercompensates, growing back stronger in anticipation of an increased workload. Without rest, you will not thrive as an athlete. Resting at the end of a yoga routine or as a stand-alone practice will help you recover faster and more completely, bringing balance into your nervous system and your life.

For corpse pose (see figure 3.14), rest on your back, with your spine neutral and your arms and legs spread. Relax everywhere as you rest and breathe. As you notice tension or thoughts intruding, release and let go.

Beyond the physical benefits of the practice, yoga can teach you equanimity, maintaining a sense of balance even in the face of changing circumstance. This comes in extremely handy both in triathlon and in life. Some of this benefit comes organically through the physical practice; some comes through studying breath exercises and meditation. Seek out local resources by talking to the owners of your local yoga studios. A regular yoga practice will bring longevity, appreciation, and balance to your training and improve the quality of your life.

anusara—An alignment-oriented approach developed by American John Friend, anusara focuses on “heart openers,” specifically back bends, which in their more gentle forms are of good use to athletes, especially triathletes who spend hours each week riding in aerobars or sitting at desks.

anusara—An alignment-oriented approach developed by American John Friend, anusara focuses on “heart openers,” specifically back bends, which in their more gentle forms are of good use to athletes, especially triathletes who spend hours each week riding in aerobars or sitting at desks. Hot Yoga

Hot Yoga