Kristen Dieffenbach and Michael Kellmann

High-performance training is high stakes. From the pool deck of the local sprint series through to the iconic full Ironman, triathletes of all levels train with a unique intensity and sense of purpose. Triathletes, almost by common definition, are driven people who live to go the distance and beyond. Although the culture of “more is better” permeates many sports, the multiple elements of triathlon make high training demands and expectations even more routine. When things don’t go as planned and performance suffers, athletes react poorly to the suggestion they may be doing too much. Performance disappointments are met with assumptions of personal weakness, failure, and the fear of not doing enough. Ironically, the common response is to push harder and train more, compounding an already negative cycle.

Triathlete magazines, blogs, and discussion groups routinely contain articles and threads from athletes regarding feeling burned out, concerns about overtraining, and the battle to achieve balance. Professional triathlete Mark Allen (2010), in discussing his early training methods, remarked, “Every run, even the slow ones, for at least one mile, I would try to get close to 5 minute pace. And it worked . . . sort of. I had some good races the first year or two, but I also suffered from minor injuries and was always feeling one run away from being too burned out to want to continue with my training.”

In his online blog, four-time Swedish duathlon champion and Swedish Ironman record holder Clas Björling writes frequently about the toll overtraining has taken on his career, and in 2008 he posted about his need to take a full year off because of overtraining and burnout and the slow recovery process. Paula Newby-Fraser, Dave Scott, and many others have discussed their experiences with the setbacks, disappointments, and injuries related to overtraining in numerous interviews. If even elite-level athletes aren’t immune, it can seem as though overtraining is a necessary evil.

Yet despite the frequent discussion of the consequences and the concern over its impact, overtraining is not as well understood as it needs to be. Although pushing hard will always carry with it the potential for both positive and negative outcomes, athletes and coaches can be empowered to greatly reduce the potential problems. Overtraining does not have to be an inevitable experience. This chapter discusses the key interactions between stress and recovery in the training process as well as the importance of considering the whole athlete, and it provides tips and suggestions for finding the optimal training balance.

Understanding Overtraining and Recovery

Most athletes and coaches today understand, at least on some level, the risks of overtraining and the value of recovery. Unfortunately, exactly what these risks are, how they influence training and performance, and what can and cannot be done about them is not often well understood. Further, the available knowledge is not used enough to enhance training efforts as a crucial part of a healthy, balanced training equation.

The uncertainty regarding overtraining and the role it plays in optimal performance and training planning is understandable given that confusion over terminology and causes exists in the scientific literature as well. Researchers use a wide variety of terms such as overwork, overreaching, overstraining, staleness, burnout, overfatigue, and short- and long-time overtraining to describe the wide range of athlete experiences. Some theories isolate and emphasize hormonal, immunological, or training factors, while others take a more global or holistic approach, considering the whole athlete and the interrelationship of many elements. Further, current laboratory-based tests to evaluate overtraining are either inconclusive or impractical for routine monitoring of training and the necessary early detection. To date, sport scientists have not provided a singular definition or clear diagnosis for overtraining, and the more that is learned about the continuum and complexity of the experience, the more it is clear that a simple diagnostic tool or solution is unlikely.

Recognizing when athletes are overtrained is an important concern. In what Canadian researcher Judy Goss (1994) has called “the paradox of training,” the same workouts designed to push physical limits in an effort to elicit best performances also create an optimal environment for overdoing it. Athletes and coaches anticipate and even welcome a certain amount of fatigue that accompanies hard training. However, the state of being overtrained is recognizable as an ongoing plateau in performance that does not improve with short amounts of rest and recovery. Unfortunately, it is difficult to quantify exactly how long a time and how much rest determine the difference between normal overreaching and something more troubling because of the unique individual nature of overtraining. The better coaches and athletes understand the experience and related elements, the better their chances of finding and navigating the fine line between too much and optimal preparation.

The consequences of overtraining can have a significant impact not only on performance but also on an athlete’s well-being and overall quality of life. Researchers have catalogued more than 200 different symptoms in overtrained athletes. The most commonly associated warning signs associated with overtraining include depressed mood, general apathy, decreased self-esteem and performance, emotional instability, restlessness, irritability, poor sleep, weight loss, loss of appetite, increased resting heart rate, hormonal changes, and the absence of performance improvements. Athletes experiencing overtraining also often exhibit an increase in injuries, a slower injury recovery time, and an impaired immune system that can lead to problems such as upper respiratory infections (Kellmann 2002; Peterson 2003). Most of the symptoms can be recognized by coaches and athletes if they pay attention and are aware of their potential significance. However, no single symptom works as an indicator alone. It is the combination of symptoms within the context of training expectations that should raise a red flag that something is wrong.

Since the 1970s, the principles of periodization and sport science research have had an increasing impact on coaching. Coaching triathletes has evolved into a detailed science itself. Athletes run, swim, bike, and lift weights, with shifts in volume and intensity to build a proper base, develop strengths, build weaknesses, and adequately taper for peak performance following the principles of periodization. Sport science research indicates training methodologies such as monotonous training programs, more than 3 hours of training per day, failure to alternate hard and easy training days or to alternate 2 hard days followed by an easy training day, no training periodization and respective regeneration microcycles after 2 or 3 weeks of training, and lack of rest days can all contribute to the physical aspect of overtraining. Yet, even when the science of training is carefully applied and potential pitfalls such as those mentioned are avoided, overtraining may still occur, indicating there is more that needs to be considered.

In both overtraining and underrecovery, athletes see a decline in performance. However, there are key differences to note between the two. Training requires that athletes be pushed beyond their comfort zone. This overreaching causes fatigue, muscle soreness, and short-lived drops in performance, all of which are expected and necessary to elicit changes and gains. However, when prolonged overreaching slips into overtraining, a longer-term decline in performance that is harder to reverse affects the athlete both physically and psychologically. In contrast, underrecovery, the lack or absence of adequate recovery activities based on an athlete’s physical and psychological needs, has been found to be a clear cause of overtraining. Although no clear, noninvasive means of determining when overreaching becomes overtraining is available, research has found that preventing underrecovery through the active and proactive enhancement of recovery can diminish overtraining. Therefore, understanding and implementing recovery enhancement into a coaching plan is an active approach to prevent overtraining among athletes.

Symptoms of Overtraining

Symptoms of Overtraining

Impaired performance

Impaired performance

No supercompensation in response to taper or rest

No supercompensation in response to taper or rest

Increased resting heart rate

Increased resting heart rate

Weight loss

Weight loss

Loss of appetite

Loss of appetite

Increased vulnerability to injuries

Increased vulnerability to injuries

Hormonal changes

Hormonal changes

Depressed mood

Depressed mood

General apathy

General apathy

Decreased self-esteem, emotional instability

Decreased self-esteem, emotional instability

Restlessness, irritability

Restlessness, irritability

Disturbed sleep

Disturbed sleep

Recovery is an everyday word in training. Coaches commonly prescribe rest between intervals and talk about recovery between efforts within workouts, but what is recovery in the larger scale of overtraining and underrecovery concerns? Poor recovery, or underrecovery, is associated with poor mental and physical outcomes, including overtraining and burnout. Proper individual recovery occurs at psychological, physical, and social levels and includes both action-oriented things athletes do and the environment they are in. In 2001, researchers Kellmann and Kallus established a list of general recovery features to help coaches and athletes enhance performance and the overall sport experience. They suggest that recovery is a process that occurs over time. Like training and other stressors, recovery is cumulative and can come from multiple sources. And finally, the quality and quantity of recovery required, allowing an athlete to achieve or maintain balance, are dependent on the nature and level of stress experienced.

It can be misleading to view recovery as merely the absence of activity. Researchers Löhr and Preiser (1974) have suggested that recovery does not need to be passive relaxation activities. Depending on the nature of the situation and needs of the person, recovery can be associated with activity in several ways. Activities that provide a positive recovery or revitalization cause eustress, or positive stress (Selye 1974). The concept of positive stress helps explain how a hard training effort, while physically stressful, can simultaneously be a source of recovery, or positive eustress, for psychological stress the athlete has experienced. An analogy can also be made to the common weight-room activity of circuit training. During circuit training, an athlete alternates activities that stress different muscles while allowing previously stressed muscles to rest. Similarly, alternating activities such as training (physical stress) and learning in a classroom or work setting (mental or cognitive stress) allows for alternating recovery and can contribute to a personal sense of balance and well-being. Thus it is possible for different systems within an athlete to simultaneously work and recover during selected activities. Intentionally varying the type and nature of different sources of stimulation or stress can help facilitate other systems that are recovering, contributing to the overall balance of the whole person.

Just like training, recovery is not a one-size-fits-all proposition. Individualization of recovery is essential. Additionally, recovery flexibility, or having multiple recovery options, is important to help an athlete adjust and match his changing needs. This is particularly important for recovery activities that might be out of a person’s control or that may be difficult to obtain or achieve. It is also important for athletes to have backup recovery strategies. Having alternatives can reduce the potential contributing stress an athlete may experience worrying about meeting recovery needs, a situation that obviously would only further compound the stress overload problem.

As noted, recovery comes in many forms. Typically, the types of recovery can be sorted into three categories: passive, active, and proactive. The concept of active recovery is a familiar one in the lexicon of training. Coaches frequently prescribe active recovery training sessions on light-load days, at the end of hard workouts, or at the end of a season to facilitate faster recovery. Passive recovery, perhaps the most familiar recovery concept (though less enthusiastically embraced by athletes and coaches as part of the training equation), encompasses sitting or lying quietly. Of note, passive recovery is also characterized by treatment modalities designed to facilitate recovery (e.g., massage, compression pants, hot and cold baths, steam baths, saunas). The physiological benefits of such treatments are a growing area of applied sport science, with high-performance facilities such as the U.S. Olympic Training Centers and the Australian Institute of Sport investing in recovery centers to provide athletes with access to these types of passive recovery activities.

The third category, proactive recovery, includes self-initiated activities done in anticipation of recovery needs. An athlete may engage in proactive recovery activities such as muscle relaxation and stretching as a part of her training and competition routine. These activities, embedded within the training process, diminish the accumulation of fatigue during the overall training experience, allowing more training stress adaptations to be gained. As with other recovery techniques, proactive recovery tactics are not limited to training-related applications. Taking a walk at lunch during the business day or taking time to chat with a friend are self-initiated activities that can provide a positive lift and help keep stress from accumulating.

The quantity and quality of recovery that any activity can provide are related to the situation in which it occurs. For example, sleep is widely acknowledged as a key component of physical and psychological rejuvenation. But sleeping in a noisy dorm or in a room that is too hot or too cold will provide less-than-optimal results, and the efforts to fall sleep may produce more stress. Individual assessment is an important factor in whether or not the situation is contributing negatively. To return to the sleep example, a person used to sleeping in the country may find that the street noises heard in a city hotel have a negative impact on the quality of his sleep environment, while another athlete may not even notice the noises at all.

Balancing Stress and Recovery in Life

Laps, miles, and lifts place a physical stress on the training athlete. Although it would be nice if athletes trained in a vacuum with nothing to do but work out, the reality is always more complex. Specifically, athletes are routinely exposed to a wide variety of daily personal and environmental stressors in addition to their training load. Stress, though commonly associated with negative feelings, can come from any source—physical, psychological, or social—that places a demand on an athlete and her resources. Understanding the whole athlete and her whole experience is an important aspect for individualized training and the prevention of negative consequences related to overtraining and underrecovery.

Regardless of the source, all stressors have an impact. The amount will depend on several factors, the most important of which is how the person perceives the situation. A situation that is perceived to be stressful or draining will have a larger impact. A situation that requires time or energy to handle or that takes away from recovery activities such as quality sleep will also increase the impact. Even routine things such as the daily commute, relationships, and work duties all take a toll. The combination of life stressors and the routine changes in training intensity and volume create the cumulative stress load the athlete experiences. It is this potential source of imbalance between a person’s level of stress and recovery that creates the optimal environment for overtraining.

In addition to the individual sources of stress and recovery resources, an athlete’s personal approach to challenges is an important element in understanding the whole athlete. Characteristics such as optimism, resilience, hardiness, and mental toughness influence how athletes perceive the stress and recovery they experience. Optimistic people see the positive, or “glass half full,” side of situations. Hardiness and mental toughness are related concepts that describe people who are inclined to see things as challenging rather than problem focused and who focus their energies on their own efforts to facilitate change. Although an athlete’s natural disposition may be more or less positive, it isn’t set in stone. Through practice and reinforcement, positive characteristics can be developed and strengthened.

Ultimately, understanding and valuing the whole athlete and his approach to situations provides coaches with key clues to help the athlete create the best environment for preventing overtraining and underrecovery problems. Communicating openly, asking perceptive questions, and listening carefully to athletes’ responses allows coaches and the athletes themselves an opportunity to better understand recovery needs.

Ask an athlete to describe her training and the common response will be a detailed account of hours per week, miles per day, workout times, swim sets, and other related details. Ask a coach to explain an athlete’s training plan and the response will be similar, with perhaps an included explanation of the various anticipated physiological responses associated with the particular phase or workout emphasis. Unfortunately, despite the integral relationship between stress and recovery demands, few athletes and coaches actively consider recovery-based activities as a part of the training plan, and even fewer regularly assess training within the broader context of life. Recovery is often assumed to occur in the spaces between workouts, without much thought to what is actually needed or how other life stressors might interfere with these activities.

Prevention of underrecovery, and as a result overtraining, necessitates that increased recovery efforts occur with increases in stress. When this doesn’t happen, a negative cycle of mounting stress without repair (physical, psychological, or both) will occur. As stress levels continue to build and are met with inadequate recovery, the impact of the stress and the availability of adequate recovery continue to be compromised. A simple example can be found in the increased nightly sleep needs that coincide with training increases. All other things being equal, when an athlete increases weekly training time, nightly sleep needs will increase in response. It is the body’s natural response for recovering properly. Not allowing for adequate sleep to occur as training demands increase not only affects an athlete’s mood but also inhibits key physiological recovery responses that occur during proper sleep cycles—hardly a model for achieving personal best.

Just as training is made up of different types of efforts, such as long, steady endurance or short, high-intensity sprints to address issues of specificity and system development, the quality and quantity of recovery efforts need to be varied. A hard run might require recovery activities such as an easy cool-down, an ice bath, proper postrun nutrition and hydration, and a good night’s sleep to optimize gains and maintain balance. A stressful day at work may benefit from the hard run as a form of recovery but may also require another form of recovery, such as being able to talk to someone or enjoying quiet time to unwind and lower the stress level. Only some of these elements are included directly in an athlete’s training plan, but ultimately they are all essential for optimal performance. Both the coach and athlete must understand and account for the multiple sources of stress the athlete experiences to develop and implement appropriate recovery strategies.

Anticipating Overtraining

All the discussions involving training, overtraining, stress, and recovery remain purely academic and without much use unless coaches and athletes have the tools they need to understand, evaluate, and apply this knowledge to the benefit of improved performance and increased enjoyment. Modern training calls on a wide variety of tools to help athletes and coaches quantify training. Variables such as distance, speed, heart rate, power, oxygen saturation, and blood lactate can all be easily and relatively inexpensively monitored. Although they provide a wealth of information for tweaking and managing training load, these measures, unfortunately, do not indicate that something is amiss until it is too late for the necessary early intervention.

First and foremost, it is crucial to acknowledge the unique individual and situation-dependent nature of all stress and recovery demands. Each athlete will have a unique experience with training and life stressors and unique recovery resources and needs; in addition, each athlete’s responses and needs will differ at different points in the training season. Determining and monitoring key training and life variables and responses can help both coaches and athletes better understand the athletes’ needs as well as their current overall balance status. In the long term, regular monitoring provides a wealth of information for performance assessment and accurate planning.

A sensitive recovery indicator that can be easily observed is the quality and quantity of sleep. Often overtrained athletes experience problems falling asleep at night. Circling thoughts about training progress or performance goals, muscle stiffness, or other incidents within and outside the training environment may keep athletes awake. Sometimes it takes 60 minutes or more to fall asleep. If this occurs for a longer period of time, such as several weeks, it needs to be considered as a symptom of overtraining and should be discussed with supporting experts and the coach.

Logbooks, electronic records, or old-fashioned paper and pencil are common ways for coaches and athletes to both track and share training data. Many options are available for monitoring recovery and can easily be incorporated into the training-related data that athletes already compile. Specific and nonspecific to recovery, research-based measures such as the Profile of Mood States (POMS; McNair, Lorr, and Droppleman 1971, 1992), Borg’s rating of perceived exertion (RPE; Borg 1998), the Recovery-Cue (Kellmann, Patrick, Botterill, and Wilson 2002), and total quality recovery (Kenttä & Hassmén 1998, 2002) can be adapted to monitor balance status.

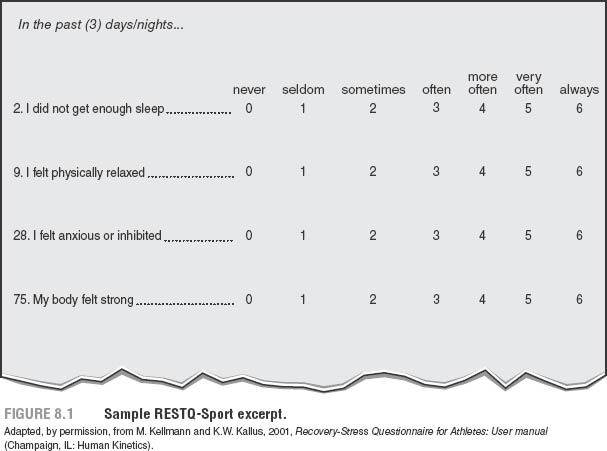

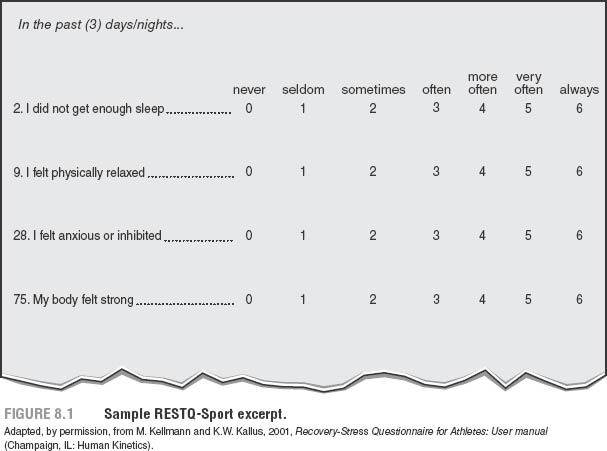

Another more detail-specific measure for monitoring an athlete’s stress and recovery levels is the Recovery-Stress Questionnaire for Athletes (RESTQ-Sport; Kellmann and Kallus 2001). This measure looks at sport- and life-specific areas of both perceived stress and perceived levels of acquired recovery and has proven useful in monitoring an athlete’s responses over time. The RESTQ-Sport has been used in various sports (e.g., triathlon, swimming, soccer, rugby) and by many nations to monitor the impact of training during the preparation camp for world championships and Olympic Games. Evaluation of the instrument shows that changes in training volume were reflected by significant changes in RESTQ-Sport scales (Kellmann 2010).

Overview of the RESTQ-Sport

Overview of the RESTQ-Sport

The RESTQ-Sport asks you to respond to a series of questions, using a six-point scale from never to always, to indicate the frequency you have done something (“I put off making decisions”) or felt something (“I laughed”) in the previous 3 days. You select the answers that most accurately reflect your thoughts and activities, indicating how often each statement was right in your case, in terms of performance during both competition and practice. Here are a few sample questions from the questionnaire:

The results are created by summing your responses across 19 scales of the RESTQ-Sport. The scales fall into four categories: general stress, sport-specific stress, general recovery, and sport-specific recovery. These scale scores can be easily plotted on a graph, allowing you and your coach to watch for trends and changes in your behaviors and perceptions related to stress and recovery. Ideally, you will demonstrate a moderate to low score for stress experienced. More important, you should experience a matched or higher level of perceived recovery, which will be seen in higher recovery scale scores.

Preventing Overtraining

Regardless of the level of competition, the consequences associated with overtraining not only have a devastating impact on hard-sought goals but also take a personal toll on athletes. Unfortunately, both professional and recreational athletes have reported experiences with overtraining. Frequently cited causes of overtraining include too much stress and pressure, too much practice and physical training, physical exhaustion and all-over soreness, boredom because of too much repetition, and poor rest or lack of proper sleep. As noted, adopting a balanced approach to training and a holistic view of the athlete can play a key role in maintaining a positive stress–recovery balance. Coaches and athletes need to be aware of both training factors and nontraining factors (e.g., work, school, travel, relationships) that contribute to an overall sense of fatigue. Further, they need to be aware of recovery opportunities and resources to ensure the athletes can strive for optimal balance.

Achieving optimal training requires an educated, self-aware, and proactive approach on both the part of the coach and the athlete. Both need to be aware of the symptoms of overtraining, have an awareness of the importance of stress–recovery balance, understand the individual athlete’s needs and resources, and be able to keep the sport experience in perspective. For their part, athletes need to be honest with themselves and their coaches about stress levels, injuries, and training responses. Coaches should strive to communicate with athletes, carefully listen to the responses, and act appropriately. Further, coaches can enhance an athlete’s perceived value of recovery efforts through modeling positive behaviors, making optimal recovery a part of routine training plan discussions, and designing careful individualized training.

Keeping competition fun and in perspective may be one of the most important elements for maintaining a positive stress–recovery balance. Unfortunately, it can also be one of the most challenging to implement in the current intense culture of even recreation-level events. Overemphasis on outcomes such as winning or age-group placement increases the pressure and stress associated with competition. Comparison-based outcomes are influenced by many factors outside a person’s control, leaving the athlete powerless to control many facets that determine the results. For example, you have no control over which competitors show up, what direction the wind is blowing, or whether or not the small piece of unseen glass punctures a tire. Emphasizing the personal challenges that relate to the elements you do have control over, such as personal level of effort, smart implementation of a personal training plan, personal preparation, and how you handle unplanned stressors such as a flat tire, are empowering and help maintain proper perspective.

Another simple yet complex concept is recognizing what exactly recovery is and isn’t. For many athletes, the concept of resting is synonymous with being lazy. Telling an athlete to take a day off can get twisted into “you can’t handle it.” Many endurance athletes fear the day off, and bragging about miles and days of consecutive training is a common phenomenon. Triathletes are prone to experience overtraining because of their desire to train for swimming, biking, and running at the same time. It is essential for coaches to teach and reinforce that recovery is much more than just doing nothing. Recovery is an essential active process that is the “yin” to training effort’s “yang.” As professional coach Hunter Allen and exercise physiology professor Dr. Andy Coggan (2010) say, fitness plus freshness is the proper equation for peak form.

Recovery encompasses a wide range of both active (e.g., light exercise, stretching) things athletes need to make time for as well as more passive elements such as quiet time to unwind and supportive relationships that athletes need to create or seek out. Coaches and their athletes should work together to brainstorm specific active and passive recovery choices and to match up the appropriate recovery to stress level combinations to ensure a healthy and productive training plan. Coaches should help athletes develop both short-term (in practice, after training) and longer-term recovery strategies. It is also important that athletes recognize and consider multiple levels and types of recovery. Ultimately, the goal of the positive recovery stress equation is always homeostasis, or balance. Be sure to keep in mind that balance is a temporary state. Once achieved, the process always starts all over again with the next training session.

In the training process, a coach is responsible for creating a personalized goal-based plan. An appropriate plan can be created only after all the information has been collected and evaluated. Understanding the complete cycle from stress through recovery creates a whole picture, allowing for optimal personalization and timely modifications. Within the process, an athlete is responsible for listening and honoring both the drive to push harder and the need to recover appropriately. Working together, a coach and athlete can use their understanding of the stress–recovery balance to reduce training frustrations, push performance to new levels, and enhance the overall sport experience.

Symptoms of Overtraining

Symptoms of Overtraining Impaired performance

Impaired performance No supercompensation in response to taper or rest

No supercompensation in response to taper or rest Increased resting heart rate

Increased resting heart rate Weight loss

Weight loss Loss of appetite

Loss of appetite Increased vulnerability to injuries

Increased vulnerability to injuries Hormonal changes

Hormonal changes Depressed mood

Depressed mood General apathy

General apathy Decreased self-esteem, emotional instability

Decreased self-esteem, emotional instability Restlessness, irritability

Restlessness, irritability Disturbed sleep

Disturbed sleep