Wear a brightly colored cap to be visible to other swimmers, lifeguards, and boats.

Wear a brightly colored cap to be visible to other swimmers, lifeguards, and boats.Open-water swimming is one of the scariest parts of a triathlon. The murky water; the other competitors; and the lack of lanes, walls, and lines to follow can intimidate even the most fearless competitor. Using the knowledge provided by experienced athletes and coaches can make the first leg of a triathlon more enjoyable and full of success. This chapter covers many aspects of open-water swimming, including training, the start, drafting, transitioning to the bike, and much more, all developed through countless races, learned after making many mistakes, and resulting in a lot of success.

Most triathlon swims take place in the open water, and for a good race performance, open-water training sessions are essential in the weeks before your event. But before diving into the nearest lake or ocean, take a few precautions for your personal safety:

Wear a brightly colored cap to be visible to other swimmers, lifeguards, and boats.

Wear a brightly colored cap to be visible to other swimmers, lifeguards, and boats.

Tell someone where you are going and how far you are swimming.

Tell someone where you are going and how far you are swimming.

Swim in a group with other athletes, or have someone stay close by in a boat.

Swim in a group with other athletes, or have someone stay close by in a boat.

Check with the local authorities to receive permission to swim in the open water.

Check with the local authorities to receive permission to swim in the open water.

Stay alert, and be aware of your surroundings at all times.

Stay alert, and be aware of your surroundings at all times.

Also, open-water swimming can help you practice in ways that more closely resemble a race course. Create a practice course using buoys made out of brightly colored plastic jugs tied to a weight or natural landmarks that are tall and easily observable. Use these open-water swims to practice sighting and turning at the buoys. When swimming with other athletes, practice drafting, passing, and dealing with the chaos that occurs at the start and at turn buoys. Learn how to quickly find the strap and unzip your wetsuit while jogging out of the water. Find open water that closely mimics an upcoming race environment to get comfortable with the water conditions (e.g., colder temperatures to practice with a full-body wetsuit).

Although open-water training is necessary as you get closer to race time, most swim training for triathlons takes place in a pool. Most athletes feel more comfortable training in the safety of a pool and enjoy participating with swim groups at local aquatic centers. The best pool is of standard length, such as 50 meters, 25 meters, or 25 yards, and is set up for lap swimming. Small or kidney-shaped backyard pools found as added amenities at homes and hotels may do in a pinch, but an actual lap pool, designed for swimming, is a far superior place to train. Even so, the safe and clear conditions of swim training in a pool do not fully prepare you for the situations that arise in open-water events. Lap pools offer clear water, lane markers, and lines on the bottom of the pool, while open-water courses are usually murky, and directional buoys are few and far between. The following drills are open-water specific and can be used in the pool to help prepare you for some of the open-water conditions you will encounter.

Tarzan. Just like any other muscle, the neck needs to be prepared for sighting countless times during the race. This drill simply requires you to swim freestyle with your head out of the water. The body’s position changes when your head is lifted out of the water. This activity teaches you to arch your back and kick hard to keep your feet near the surface.

Tarzan. Just like any other muscle, the neck needs to be prepared for sighting countless times during the race. This drill simply requires you to swim freestyle with your head out of the water. The body’s position changes when your head is lifted out of the water. This activity teaches you to arch your back and kick hard to keep your feet near the surface.

Turning at the T. This activity is a great way to simulate the continuous swimming of open-water events. Instead of swimming all the way to the wall, turn or flip 2 or 3 meters before the wall. This removes the small break you receive at each wall and can make any long swim feel more challenging.

Turning at the T. This activity is a great way to simulate the continuous swimming of open-water events. Instead of swimming all the way to the wall, turn or flip 2 or 3 meters before the wall. This removes the small break you receive at each wall and can make any long swim feel more challenging.

Draft pack. Several swimmers in the pool can simulate the feeling of drafting other swimmers during a race. Swimmers can practice positioning themselves behind the lead swimmer and learn how to not touch their feet with every stroke. After each 100, the lead swimmer should move to the back of the pack so the group is continually rotating.

Draft pack. Several swimmers in the pool can simulate the feeling of drafting other swimmers during a race. Swimmers can practice positioning themselves behind the lead swimmer and learn how to not touch their feet with every stroke. After each 100, the lead swimmer should move to the back of the pack so the group is continually rotating.

Recovery stroke. Learn to swim another stroke, such as backstroke or breaststroke, to feel more comfortable in the water. Back and breast strokes are good safety strokes you can switch to when you are feeling tired during an open-water swim or when you are having trouble locating a course buoy. Practice these strokes in the pool, and use them to keep moving forward during a long swim instead of hanging on the wall to rest.

Recovery stroke. Learn to swim another stroke, such as backstroke or breaststroke, to feel more comfortable in the water. Back and breast strokes are good safety strokes you can switch to when you are feeling tired during an open-water swim or when you are having trouble locating a course buoy. Practice these strokes in the pool, and use them to keep moving forward during a long swim instead of hanging on the wall to rest.

To gain as much information about the race and to be able to use that information to your advantage tactically, you should first learn the rules front and back as they apply to the race you are participating in. Also, take time to assess the water and scout the swim course before the start of the race. Many events open the course for practice a day before the race so that athletes can use this time to get to know specifics about the water and weather conditions in addition to the course. With limited time on race morning, the details picked up during a practice swim can provide good data during the race.

Knowing and understanding the race rules as they apply to the swim leg of a triathlon is an invaluable tool. Rules that describe legal speedsuits and wetsuit thickness are constantly being reviewed and updated with advancements in technology. Ironman and 70.3 events generally follow USA Triathlon rules, but several technical rules and penalty enforcements have been relaxed. Be aware of the changes from one race to another.

The USAT rules that apply to the swimming leg of a triathlon are very straightforward. Swimmers may use any stroke for forward moment. Goggles and masks are permitted, but artificial propulsion devices (e.g., fins, paddles) are not allowed. A swimmer must complete the entire course and swim around all required buoys. Swim caps that are provided by the race management must be worn at the start of the race. According to Section 4.2, a swimmer may use the bottom to make forward progress. This allows athletes to stand and rest or dolphin dive through shallow water and underneath waves. Swimmers may touch or hold onto buoys and boats; however, they cannot use these objects to make forward progress. The general USAT rules of sportsmanship, conduct, and abandonment of equipment also apply to the swim course.

For more information and the most updated rules, see the following:

USA Triathlon competitive rules at www.usatriathlon.org

USA Triathlon competitive rules at www.usatriathlon.org

USA Triathlon’s list of approved speedsuits and skinsuits at www.usatriathlon.org

USA Triathlon’s list of approved speedsuits and skinsuits at www.usatriathlon.org

USA Triathlon’s 2013 wetsuit rule FAQ at www.usatriathlon.org

USA Triathlon’s 2013 wetsuit rule FAQ at www.usatriathlon.org

Ironman and 70.3 rules and FAQ at www.ironman.com

Ironman and 70.3 rules and FAQ at www.ironman.com

ITU events competition rules at www.triathlon.org

ITU events competition rules at www.triathlon.org

Know as much about the water conditions as possible before race morning. Most practice swims are held during afternoon hours. The water and weather conditions can be very different in the early-morning hours, so talk with the locals and question the lifeguards about conditions at race time. Ask about typical wind speeds, wave conditions, current and tidal flows, and water quality. If there is no local knowledge available, perform a float test during the practice swim. Lie on the surface, and make note of the direction and speed you are drifting in order to detect water-flow currents or strong surface winds. When you are racing perpendicular to the current direction, make necessary adjustments to your directional heading to prevent being swept past a turn buoy. A shorter line can be swum between buoys by compensating for currents during the race. For example, if the ocean current is moving south, position yourself to start as far north on the beach as possible. This will allow you to use the flow of the current to get to the first turn buoy much easier and faster.

Pay attention to the quality of the water, and know that this can have serious effects on the outcome of your race. In saltwater events, be diligent about not swallowing or drinking an excess amount of water. Consuming too much seawater can lead to dehydration as the body tries to balance internal sodium levels. Also, be aware of the weather reports when racing in freshwater events. A recent rain can wash foreign substances into the water, which can lead to high levels of bacteria. Taking precautions, such as having antibiotics on hand, is not uncommon among elite triathletes who swim in foreign countries on a regular basis.

Races will continue as scheduled during a light rain shower but be postponed or canceled in the case of extreme downpours and lightning. Check online for rain dates and the organization’s policy on weather-canceled events. Before signing up for any event, research the typical weather patterns on the race date, and prepare yourself for the worst-case scenario. Pack clear and metallic goggles to be ready for dark and light weather conditions on race morning.

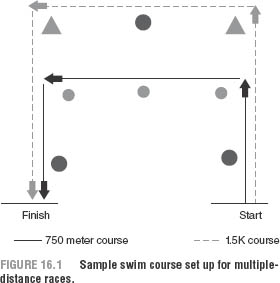

Every athlete should learn the shape and direction of the swim course. Determine if you should stay to the left or the right side of the buoys. Memorize the total number of buoys in each direction, and note if the color and shape of the turn buoys are different. This is especially important when different-length courses are marked at the same time. For example, take a look at figure 16.1. This is a common setup for an event with a 750-meter and a 1.5K swim course. This course-within-a-course design allows the event directors to maximize the number of buoys they have at their disposal, but it can create some confusion for the athletes.

Athletes competing on the 750-meter course should be aware that they make a turn at the first buoy. Mistakes are easily made when an athlete does not make this turn because she sees another buoy in the distance. The second turn on the 750-meter course is after the swimmers pass three red buoys. The 1.5K course has triangle-turn buoys. These are important buoys, and some races will use buoys of different shapes or colors to mark the turns. An athlete on the 1.5K course needs to know that the red buoys are not part of his course.

Use the bright daylight hours during a practice swim to pick out high landmarks that can be sighted during the race. When you are surrounded by other swimmers or in choppy and wavy conditions, the buoys and finish chute are not always visible. Find something such as a building, tree, or radio antenna that is directly in line with the course. Use these landmarks for general sighting to stay on course. Also check the bottom surface at the start and finish areas, and make note of the degree of slope from shore. Practice run-ins, and count the number of steps from the starting line into knee-deep water. Then count the number of dolphin dives to waist-deep water. Use these numbers during the race as a general guide when the visual conditions are not perfect.

Benefits of a Prerace Warm-Up

Benefits of a Prerace Warm-UpTo prevent cold and stiff muscles at the beginning of the race, a warm-up is necessary. Spend enough time in the water to activate muscles and increase heart rate. Athletes who take a long time to get activated should arrive early to benefit from the greatest amount of time in the water. In addition, water that is very cold can be shocking to the nervous system and cause panic and shortness of breath. In this situation, use any opportunity to get in the water before the race starts and adapt to the cold. This can reduce panic, shock, and pain at the start of the race. A prerace swim in cold water also provides an opportunity for the body to heat a layer of water between the skin and wetsuit, keeping you warm during the race.

However, triathletes may not be able to warm up in the water, depending on venue rules that prohibit people in the water (e.g., Florida 70.3); whether athletes have access to the water (e.g., Escape from Alcatraz); or poor time management by an athlete. Also a good prerace warm-up can be negated if an athlete becomes chilled while waiting for the race to start. In many cases, the early-morning air temperature will be much cooler than during the race, so staying dry can also mean staying warm. To ensure this, toss a cheap pair of thick socks and mittens into a prerace bag. These items can be worn on the beach and discarded before the start.

If a warm-up in the water is not an option, stretch cords or resistance bands are a great item to include in a prerace bag. Tie each end into a loop around a tree or pole, or grasp the tubing in each hand, and perform a few minutes of light dryland swimming movements. The resistance provided by the elastic band allows the arm and shoulder muscles to activate and warm up.

Also, a sufficient amount of running, cycling, yoga, or any activity that will raise the heart rate and increase blood flow can be substituted for swimming.

The start of a triathlon is the most chaotic moment of multisport. With a well-planned strategy, any triathlete can create an advantage for himself before the gun is fired. The simplest way is by choosing a starting position.

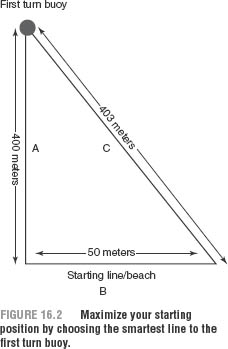

Take a look at figure 16.2. The shortest path from the starting line to the first buoy is the straight line A. Many athletes crowd into this position, assuming it is the fastest path to get to the first turn buoy. If starting line B is 50 meters wide, a simple calculation of Pythagorean’s theorem shows that line C is only 403 meters. The time it takes to cover a distance of 3 meters in open water is insignificant when the hazards avoided by starting away from the crowd are considered. Although an outside starting position has advantages, weaker swimmers will benefit less. The shortest line, A, will always provide a strong drafting area that is created by the large crowd of swimmers racing to the buoy. However, novice athletes and others not comfortable with the high-contact zones should start to the outside for a more pleasant experience.

The outside starting position can also be utilized when there is a current in the water. If the water is running north, as in figure 16.2, a swimmer starting on the southern edge of starting line B is least likely to be carried past the first turn buoy. When the race is very crowded or there is no beneficial starting position, choose a position based on the location of other athletes. Create an instant drafting position by lining up next to a slightly stronger swimmer. Follow the bubbles trailing behind the lead swimmers as soon as the race starts.

Many triathlons start on land, with a short run into the water. This is referred to as a beach start. The simple rule of thumb for a beach start is to run normally into the water. When you reach the water, lift your legs and feet up in a high-stepping run until the water is over your knees. In most situations, you can launch into your first dolphin dive when the water is above your knees (be sure to verify the slope of the ground before the start of the race). Dolphin-dive until the water is about waist high, and then begin swimming.

In an open-water start, the swimmers are all in the water and can begin swimming when the start is signaled. When a 30-second warning is announced, or if the start is imminent, put your body into a horizontal position on the surface of the water, but keep your head raised. Scull lightly with your hands, and kick lightly with your feet to maintain a stationary position at the line. When the race starts, drop your head into the water, and immediately start kicking and swimming forward.

Also, many elite athletes will have the opportunity to dive off a pontoon or stationary pier to start a triathlon. These starts are designed to give each athlete an equal position on the course. Success at this kind of start is based on reaction time, leg power, underwater kicking and breakout efficiency, and starting speed in the water. Basically, these are the same principles that apply to a start from the diving blocks into a pool. Coaching and training should be modeled similar to that of a competitive swimmer.

Triathletes have adopted many methods of moving through the open water quickly and efficiently. Some things, such as dolphin dives, have been adapted from lifeguards in action, while other tactics, such as drafting other competitors, are tricks that open-water swimmers have been doing for many years. Triathlon events take place in all types of bodies of water and conditions, so athletes must learn how to maneuver and stay competitive. The following are some very common tactics you can employ in almost any type of triathlon competition.

Dolphin dives are a quick and efficient way to move through shallow water and maneuver through breaking waves. They are named as such because the athletes look like dolphins when they dive underwater and then pop up and arc over the surface.

Start by practicing in water that is deep enough to cover your knees but does not come above your waist. Jump forward with your arms outstretched in front of your face and dive down toward the bottom. When your hands come in contact with the ground, dig your fingers into the soil, and use this leverage to pull your body forward through your arms. Grabbing the sand when diving under a powerful wave will keep you from being swept backward by the undercurrent. Then, use your feet to push off the bottom and launch your body forward along the surface of the water. Don’t forget to look forward and breathe between every dive. Bring your arms around like the recovery of a butterfly stroke, and then dive toward the bottom again. Water deeper than waist high is not efficient for dolphin diving because the momentum of pushing off the bottom and flying over the surface of the water does not carry you all the way to the bottom.

Remember, however, that when doing dolphin dives, safety is of utmost importance. Always lead with your hands and arms to prevent injuries caused by hitting the ground with your face or head. Open water can have little to no visibility, so sandbars, rocks, or other unknown objects can be lying just under the surface.

There are no lane markers or lines on the bottom in open water. Staying on course and swimming from one buoy to the next depends on how well each athlete can maintain a straight line in the water. Sighting is the term used to describe when an athlete lifts her head to look for the buoys and other landmarks while swimming. There are many ways to sight the course markers (e.g., taking a few strokes of breaststroke), but most of these methods reduce speed and efficiency in the water.

In calm water, you should lift only your eyes and nose out of the water to look forward. After sighting, turn your head to the side for a breath and continue swimming. You can sight a couple of times in quick succession to recognize and memorize the position of the buoys and other swimmers. If the immediate area is clear, and waves and current aren’t a factor, swim without sighting for a while to let you maintain an efficient stroke, resulting in a faster swim with less energy used for unnecessary sighting. In rough water, ocean waves, or other unsatisfactory conditions, however, you should sight often to maintain the most direct line between buoys. Use the same method as described previously, but lift your head higher to sight over small, choppy waves. In large ocean waves, feel the rhythm and swells in the water, and plan to sight on top of the wave to catch the best view of the course.

A swimmer is most efficient while maintaining a horizontal body position, but when the head is lifted to sight for a buoy or landmark, the swimmer is forced out of this position. When sighting, arch your back and kick extra hard to compensate for lifting your head out of the water. It is easier to return to a horizontal body position if the abdomen drops than if the legs and feet sink.

According to a study published in 2008 (Silva et al.), a swimmer on the feet of another can experience between 16 and 45 percent less drag through the water. This is very significant over distances such as 2.4 miles (3.8 km), but it has a direct impact on all open-water swimming events. Drafting can allow an athlete to finish a swim in the same time with less effort expended, or it can help a swimmer finish faster by using the same effort.

The hardest part of drafting is knowing whom to draft. Athletes who continually compete against the same people will figure out whose feet they should be following. When racing an unknown crowd, it is best to start at your own pace. As the crowd thins out after the start, settle in behind someone and draft for a while. If you think the pace is too slow, move to the side, swim ahead, and look for different feet to draft. Drafting etiquette, though, is to not touch the feet of the lead swimmer. This not only irritates the swimmer but can also slow him down. Excessive feet tapping can also lead to angry retaliations by the lead swimmer. When drafting, swim with a very wide arm entry at the front of the stroke. This will place your hands on either side of the lead swimmer’s feet.

Another type of drafting, called shorting, is where an athlete drafts on the hip, which is another beneficial location. A drafting athlete can ride the wave of another swimmer by positioning her head next to the lead swimmer’s hip. No contact is necessary between athletes. It is easier to sight when drafting in this position because the lead swimmer is not blocking the drafting swimmer’s view. An athlete in the shorting position can quickly swim over the hips of the lead athlete to change positions or swim in a different direction. Changing sides is common when drafting in a choppy or wavy course. The shorting athlete can use other swimmers as a wall to reduce the chop and battering from waves on the upwind side.

When drafting, remember you should never rely on another athlete to swim the correct course or take the shortest path between buoys. Every triathlete should sight the course to prevent misdirection, even when following the bubbles of another athlete.

Turn buoys are one of the most chaotic places in a triathlon or open-water swim. Packs of swimmers get backed up trying to take the shortest and most direct line. As a result, many people get pushed underwater, have their goggles knocked off, or experience some other form of unfriendly contact.

To escape the chaos, a swimmer can choose to swim a slightly longer route to the outside of the melee. This is a good choice for faster swimmers, timid swimmers, and smaller athletes. In most cases the excess distance swum is insignificant, but some races are so large and crowded that swimming to the outside of the group can be a poor decision. In this case, the shortest and smartest decision is to stay close to the buoy. Take short strokes with a high cadence when navigating through the chaos near a buoy. Long strokes are usually impossible, and quick strokes will keep you on top of the water and moving forward.

With no pace clocks or marked distances, properly pacing an open-water swim can be a challenge. Any experienced triathlete knows that responding incorrectly to the natural adrenaline burst at the start of a race can lead to a poor overall swim. Learning how to pace begins long before race day arrives, and every swim practice is important training for a successful open-water swim.

Pacing in open water can become simple by listening to your body and associating an effort level with a speed. During practice, label personal swimming speeds with an effort level similar to the rating of perceived exertion (RPE) scale you learned about in chapter 9:

Level 1(RPE 1-3)—I can swim at this effort for an hour.

Level 1(RPE 1-3)—I can swim at this effort for an hour.

Level 2 (RPE 4-6)—I can swim at this effort for 30 minutes.

Level 2 (RPE 4-6)—I can swim at this effort for 30 minutes.

Level 3 (RPE 7-8)—I can swim at this effort for 10 minutes.

Level 3 (RPE 7-8)—I can swim at this effort for 10 minutes.

Level 4 (RPE 9)—I can swim at this effort for 5 minutes.

Level 4 (RPE 9)—I can swim at this effort for 5 minutes.

Level 5 (RPE 10)—I can swim at this effort for 60 seconds.

Level 5 (RPE 10)—I can swim at this effort for 60 seconds.

You should associate each effort level with an internal feeling so you can recognize that level without any outside data. For example, you might associate moving from level 2 to level 3 with a need to breathe more often. Other personal cues that can be easily perceived are heart rate, kicking tempo, and muscle sensation. Use your personal swimming effort levels to map out a plan for a successful open-water swim. By recognizing personal cues in the race, you can adjust your effort level to swim at the same levels you have been training in practice.

Depending on the length of the course, athletes are typically in the water between 10 minutes and 2 hours during the swim leg of a triathlon. During this time, your body adjusts to a horizontal position. The legs are kept in a relatively straight position with minimal movement, especially with a wetsuit providing flotation. As a result, when you reach the swim exit, you can have trouble standing and moving in a vertical position. To prepare for the quick transition from swimming to standing and running, use the last 200 to 400 meters of the swim course to help your body adjust. Start by increasing the kick to warm up the leg muscles. A few small breaststroke kicks are helpful to loosen up the quadriceps and provide a light flexion stretch to the ankles and calves.

Many athletes experience a spike in heart rate during the swim exit. Prepare for this spike by kicking more and building to a higher effort level during the last 100 meters. Getting the blood moving in the lower extremities and increasing heart rate is the first step. The second step is to swim as far as possible into the shallow water. It is inefficient to try to walk or wade through deep water, and dolphin diving is dangerous because the ground slants upward. By swimming until your hands scrape the bottom, you can stand up in very shallow water and immediately start running.

Training harder is not the only way to a faster and more successful open-water swim. Learning from your mistakes, watching experienced athletes, and using a few commonsense tips can turn a choppy, cold, and overcrowded race into an enjoyable and successful experience. The little details from an event are the first to fade from your memory. Whether or not you are satisfied with your results at the finish line, jot down a couple of notes after each race. After the endorphins, adrenaline, and muscle soreness have faded, take a look at your postrace notes. Find little places where improvements can be made. Address these changes during practice so they become automatic and natural. Talk with other triathletes, and share personal stories of failures and successes in the journey to leading the pack out of the water.