Manipulate body weight. Some triathletes have a goal of losing or gaining weight, and this can be a main focus of a nutrition plan.

Manipulate body weight. Some triathletes have a goal of losing or gaining weight, and this can be a main focus of a nutrition plan.Most triathletes know that nutrition is important for race-day planning, but what you should remember is that nutrition has a profound impact during your daily training sessions, and this can affect how you adapt and prepare for race day. There certainly is a fine balance between what foods and beverages you eat, when and why you consume them, and how you implement a nutrition plan to support your individual health and physical needs. Sport nutrition has evolved quite a bit over the years, and nowadays, it is necessary to look at the big picture to properly implement a nutrition plan for achieving good health and optimal performance, and this means aligning your nutrition plan with your physical training plan. A properly periodized nutrition plan that supports your physical periodization plan will allow you to achieve better health and a higher level of performance.

Nutrition periodization is the term that describes matching your nutrition intake to your training sessions. Your nutrition program should vary, with the goal of closely matching your physical training needs so you can enter training sessions well fueled and hydrated and recover adequately in order to continue your performance improvement. It does not matter if you are training for short or long triathlons, adopting nutrition periodization will help you become a better athlete. Nutrition supports training, or as I like to say, “Eat to train, don’t train to eat.”

If you are not nutritionally prepared before a training session, you will not get the same positive physiological training adaptations as other triathletes who pay attention to what, when, how much, and why they eat. Most triathletes follow similar training phases that usually include preparatory (base and build), precompetitive, competitive (race), and transition (off-season) phases. In this chapter, I present the quantitative method of nutrition periodization, which focuses on utilizing numbers within a nutrition plan, but other methods such as qualitative (not relying solely on numbers and counting calories and grams) are also highly recommended. These methods use hunger and satiety responses as well as teach athletes about biological, habitual, and emotional hunger. They are often chosen by athletes who prefer configuring a nutrition plan based on their emotional connection with food rather than with numbers.

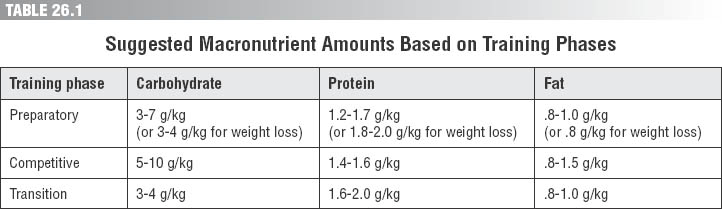

The quantitative method gives information about how much carbohydrate, protein, and fat you should eat on a daily basis (in calories per kilogram of body weight). The ranges are provided by scientific research of the amount of each macronutrient that cyclists, runners, swimmers, and triathletes need each day. There is a large range for these nutrients because they cover athletes from very short distances and durations to the very long-duration athletes who qualify as ultraendurance athletes. These ranges give you some background knowledge about how and, more important, why to follow a periodized nutrition plan. I have further separated these ranges in each training phase to give you a better idea of how your macronutrients should change based on your training changes and goals. Keep in mind that understanding the quantitative part of nutrition periodization is important at first, but it is limiting because it does not teach you the qualitative characteristics associated with eating, such as the psychological connection to food and your body’s hunger and satiety responses. Eventually, you will migrate to using fewer numbers and relying more on qualitative eating habits.

Here are the goals associated with the nutrition periodization concept to help you better understand it:

Manipulate body weight. Some triathletes have a goal of losing or gaining weight, and this can be a main focus of a nutrition plan.

Manipulate body weight. Some triathletes have a goal of losing or gaining weight, and this can be a main focus of a nutrition plan.

Manipulate body composition. Some triathletes aim for a certain body fat percentage and will manipulate their nutrition plans accordingly.

Manipulate body composition. Some triathletes aim for a certain body fat percentage and will manipulate their nutrition plans accordingly.

Improve metabolic efficiency. Nutrition periodization improves the body’s ability to utilize stored fat as energy during exercise while preserving carbohydrate stores.

Improve metabolic efficiency. Nutrition periodization improves the body’s ability to utilize stored fat as energy during exercise while preserving carbohydrate stores.

Promote a healthy immune system. Following a good nutrition plan will help support the immune system, especially during a heavy training load.

Promote a healthy immune system. Following a good nutrition plan will help support the immune system, especially during a heavy training load.

Support physical periodization. A nutrition plan should support all the physical fluctuations of volume and intensity in a training year, and thus periodizing the nutrition plan should be the first goal when it comes to looking at a triathlete’s nutrition needs.

Support physical periodization. A nutrition plan should support all the physical fluctuations of volume and intensity in a training year, and thus periodizing the nutrition plan should be the first goal when it comes to looking at a triathlete’s nutrition needs.

It is extremely rare for me, as a sport dietitian, to find a triathlete who does not have the goal of losing body fat or improving lean muscle mass. These goals definitely rank high among triathletes, and it just so happens that nutrition periodization supports these goals very well. Remember, this concept implies that you change your food intake based on your training, and by doing this, you can manipulate your body weight and body composition throughout the year. Keep eating the same volume of food when you are training more and you will run out of energy. Eat the same amount of food when you are not training much and you will gain weight. Neither is the goal under the nutrition periodization concept. As your training ebbs and flows, so should your nutrition.

Now for the numbers. The macronutrient ranges that endurance athletes eat on a daily basis, as have been cited in scientific research, include 3 to 19 grams of carbohydrate per kilogram of body weight, 1.2 to 2.0 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight, and .8 to 3.0 grams of fat per kilogram of body weight. If you measure your body weight in pounds, divide that number by 2.2 to get kilograms of body weight. Then, simply multiply the ranges throughout this chapter to individualize your plan. These ranges are large, and they reinforce the underlying message of providing these numbers to you: to let you see that an endurance athlete’s daily eating plan (1) does not stay the same throughout the year and (2) has a great amount of variance. How you interpret and use these numbers is the most important thing, and the first step is having an understanding of your physical training plan.

Before using nutrition periodization, you must first have a good understanding of what you are trying to accomplish physically in each of your training phases. Will you be following a traditional physical periodization program that emphasizes improving endurance, flexibility, and strength during base training and later adding intensity, power, and speed during the build phase? Or will you be trying to increase your speed during your base training season? It may sound odd to think about your physical training goals in a nutrition chapter, but remember, nutrition supports your physical training, so you must know where you are headed physically before you can develop your nutrition plan. Specific hydration strategies are presented in the next chapter, and thus they will not be discussed here.

More than likely you will be trying to improve your endurance, strength, flexibility, and technique during the preparatory (base) phase. You may also be thinking of shedding a few pounds or some body fat since base-season training often begins after the holidays. All these goals reinforce the fact that you must periodize your nutrition to support your training. It can be a bit tricky at first because your training load (a product of volume and intensity) will not be that high in the early part of this phase if you follow a traditional periodization model. That said, it will be extremely important for you to slowly increase the amount of food you eat as your training increases. Remember, nutrition supports your daily training. If you are not training much in the early part of this phase, then you certainly cannot justify eating a lot. If you misalign your nutrition and your training, you will actually notice weight gain. It is quite common in new triathletes who do not understand the basic idea of periodizing their nutrition programs.

Bringing the numbers back into the story, nutrition periodization for this training phase states you should eat anywhere between 3 and 7 grams of carbohydrate per kilogram of body weight. Until your training volume increases to more than 3 hours for a session, you do not need to eat very much. Try to get most of your carbohydrate from fruits and vegetables, as they are great sources of vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and fiber. Do not worry about consuming sport nutrition products such as energy bars, gels, and sports drinks. You will not need these extra calories until you start training more.

The protein recommendation is to eat between 1.2 and 1.7 grams per kilogram of body weight. Choosing protein can be difficult because some sources are higher in fat; try to choose the leanest sources such as low-fat dairy products and lean cuts of meat without skin or visible fat. Nonanimal sources of protein such as tofu, edamame, nuts, and beans are also good choices. Fat should not be thought of as the enemy of your diet. Your body requires a certain amount of healthy fat to function properly. Try to eat a lower to moderate amount of fat, .8 to 1.0 gram per kilogram, and make sure the majority is healthy fat such as monounsaturated (avocados, olives, nuts) and polyunsaturated, specifically omega-3 fats (salmon, trout, walnuts, flax). Try hard to minimize your consumption of saturated and trans fats found in processed foods, snack foods, and high-fat meats.

If one of your main goals during the base season is to lose weight or change your body composition, then you are in good company because it is one of the more popular goals among triathletes. For weight loss, I recommend shifting the numbers around a bit so your carbohydrate intake decreases to 3 to 4 grams per kilogram per day, protein increases to 1.8 to 2.0 grams per kilogram per day, and fat remains low at .8 gram per kilogram per day. The key is to decrease your carbohydrate intake to a lower (but still safe) level and increase protein to improve your blood sugar control and keep you fuller longer.

Stabilizing and controlling blood sugar can also help you become more metabolically efficient, which benefits any triathlete, young or old, recreational or professional. Metabolic efficiency is the relationship of carbohydrate oxidation (burning) to fat oxidation throughout different intensities of exercise. As the intensity of exercise increases, your body needs more carbohydrate to fuel the workout. Although this is certainly true, the take-home message is not to overfeed yourself with too much carbohydrate (especially simple sugars) throughout the day or during training. Repeatedly feeding your body a high amount of simple and refined carbohydrate may lead to adverse health issues, such as diabetes, through the development of insulin resistance; can create abnormal blood lipids, such as high triglycerides; and can create a heavier body weight. Balancing your daily nutrition while controlling blood sugar is a key goal in maintaining good health. This can be done by periodizing your nutrition plan throughout the year.

From a performance perspective, improving your body’s ability to use fat can lead to a greater use of your stored fat as energy to fuel your training sessions and even your competitions. This reduces your need for calories during training, which will significantly decrease your risk of gastrointestinal (GI) distress. This is extremely important for long-course (half Ironman and longer) athletes since athletes sometimes overeat on the bike in an effort to stay fueled during the bike and run. That is a recipe for disaster, often resulting in GI distress in the form of vomiting or diarrhea. It is also important for short-course (sprint and Olympic distance) athletes because the intensity during competitions is greater, and with that comes a decreased ability to digest and process the calories you eat during exercise. This is due to the body’s blood shunting response where, during exercise, blood is carried to the working muscles (to fuel locomotion) and away from the gut. However, if you are exercising at higher intensities and consume too many calories, the body must redirect this blood from the muscles to the gut for proper digestion. When this happens, there is a high risk for GI distress. Thus, no matter if you are training for long- or short-course triathlons, it is to your benefit (from a health and performance perspective) to become more metabolically efficient to teach your body to use more of its internal fat stores and preserve your carbohydrate stores until they are really needed (during higher-intensity exercise). By training your body to do this, you will increase your fat burning at higher intensities, which means you will be able to use more fat to fuel your training at higher intensities.

One of the easiest ways to develop better metabolic efficiency, besides training aerobically, is through proper nutrition—more specifically, implementing a good nutrition periodization plan that supports your training load as it increases and decreases throughout the year. Far too many athletes eat high-carbohydrate diets when their training load does not support it. This simply teaches your body to use more carbohydrate as energy and to store fat, which can lead to weight gain in some cases. Eating a higher-carbohydrate diet will lead to an increase in carbohydrate oxidation. This will decrease the body’s ability to oxidize fat because of a higher insulin response seen with high blood sugar, which, in turn, turns off fat oxidation. Therefore, to properly teach your body to use fat more efficiently, carbohydrate intake should be lower in the beginning of this base training phase. This does not mean you should follow a low-carbohydrate diet. Rather, the goal is to balance your carbohydrate, protein, and fat intake through proper blood sugar control so positive metabolic changes can happen.

By focusing on balancing your daily nutrition and eating good sources of lean protein and fiber from fruits and vegetables during this training phase, you can improve your metabolic efficiency in approximately 4 weeks. It does not take long to teach the body how to use fat as an energy source. However, remember that once you develop it, you must maintain it. It is very similar to your fitness level. In the beginning of your training program, you typically have the goal of improving your aerobic fitness, and then throughout the year, you maintain it with different training sessions. Developing and maintaining metabolic efficiency follow the same principles you use in your training program as you prepare your body for the race season. It is not a change that happens overnight, and it is not something you can forget about once you have it. That is why periodizing your nutrition throughout the entire year to support your physical training is so important.

One of the most important things to remember during each training phase is that the calories you put in your body immediately before, during, and after training will be different throughout the year. Your energy needs will vary because of higher and lower training loads based on your goal-competition distance. Most sprint- to Olympic-distance training programs do not exceed 2- or 3-hour training sessions, while half Ironman and Ironman training will easily exceed the 3- or 4-hour mark for individual training sessions. However, even for long-course training, volume will not be that high in the early to middle part of this preparatory training phase, and thus not many calories are needed during training.

The body normally has enough stored carbohydrate to supply 2 to 3 hours’ worth of exercise at moderate intensity. Thus, for any training session during this phase that is less than 3 hours, you will not need to consume calories. Be sure you have a metabolically efficient meal or snack (for example, scrambled eggs with fruit, peanut butter mixed with yogurt) before your training session, and then simply drink water and possibly consume extra electrolytes depending on your climate.

If you are training for long course and exceed 3-hour training sessions, you should still eat a metabolically efficient meal or snack beforehand, and there are a few guidelines you can follow after the 3-hour mark during a training session. First, eat between 10 and 50 grams of carbohydrate per hour of training. The range is large because there are many determining factors depending on your training volume and state of metabolic efficiency. Current sport nutrition research recommends eating between 30 and 90 grams per hour, but the research does not periodize nutrition recommendations. As mentioned previously, you do not need that many calories during this training phase since energy expenditure is lower. Additionally, if you have developed good metabolic efficiency, you will not need to eat as many calories during training since your body can use more fat as fuel during these lower-intensity training sessions. Depending on how sensitive your digestive system is, you can choose a wide variety of foods such as crackers, bananas, nuts, and even sandwiches. Many of the higher-calorie sport nutrition products are not needed during this training phase. Save those for the next training cycle when your intensity and energy expenditure are higher.

Second, very few triathletes even think about eating protein during a training session, but especially since this is the base training phase, it is really not necessary to consume protein because calorie expenditure is lower and thus a high number of calories is usually not needed. And, finally, fat is not needed and should not be consumed unless you are training for ultraendurance competitions and training sessions are longer than 6 hours.

After most training sessions during this phase, a well-balanced snack or meal. This could be a combination of lean protein, fruits and vegetables, a small amount of carbohydrates and a little fat, and will give you all the nutrients you need, particularly if you are training for short-course triathlons. It is simply not necessary to follow a postworkout nutrition regimen after training sessions of less than 3 hours with no high-intensity intervals. Choose a well-balanced snack, or time it so you will have your meal in the hour after you finish training, and you will be set.

For triathletes, the competitive phase means more intensity. Whether it is sprint sets in the pool, hill repeats, threshold or  O2max intervals, or track sessions, the body’s thermostat is turned up, and more calories will be expended during these types of training sessions. Short-course triathletes will not increase volume of training too much, while long-course triathletes will begin to extend past the 4- or 5-hour training session mark. The typical physical goals associated with this training phase are to improve speed, power, and economy. This adds more stress to the body and increases energy expenditure, making nutrient timing more important.

O2max intervals, or track sessions, the body’s thermostat is turned up, and more calories will be expended during these types of training sessions. Short-course triathletes will not increase volume of training too much, while long-course triathletes will begin to extend past the 4- or 5-hour training session mark. The typical physical goals associated with this training phase are to improve speed, power, and economy. This adds more stress to the body and increases energy expenditure, making nutrient timing more important.

The biggest mistakes triathletes make during this training phase are overconsuming calories (not using a periodized nutrition approach) and choosing foods that do not support metabolic efficiency. The worst thing you can do during your competition season is to significantly alter your nutrition plan. Small deviations that account for fitness level, environment, or duration of competitions are fine, but changing your daily plan too much will backfire on you.

Because of the higher intensity and frequency of glycogen-depleting workouts, carbohydrate intake can increase to 5 to 10 grams per kilogram. However, this is dependent on the specific training session. For example, a higher carbohydrate intake on a recovery or easy day is not necessary and will not be in your best interest in controlling blood sugar (and body weight). Aim to closely match your macronutrient intake based on the daily training you perform. Training of higher intensity and volume may require more carbohydrate and vice versa. This is how a periodized nutrition plan fits in the competitive training phase. The range for protein remains at a moderate level, 1.4 to 1.6 grams per kilogram. Focus on lean sources and those that are rich in branched-chain amino acids, found in animal products such as meat and dairy as well as in protein powders such as whey and soy.

The range for fat is similar to that of the preparatory phase, with the exception of athletes training for ultraendurance races. However, very few triathletes fall into this category, which is defined as distances greater than Ironman. Daily fat intake can increase up to 1.5 grams per kilogram for these athletes since they will likely need additional fat in their eating program because of the higher energy loss from longer-duration training sessions (more than 8 hours). Fat is more energy dense and will help these athletes remain in energy balance more effectively. Of course, healthier fats such as polyunsaturated (specifically omega-3) and monounsaturated fats with minimal amounts of saturated and trans fat should be the focus.

During competitive-phase sessions, there is not only an increased energy expenditure from more intense workouts but also an increased risk for GI distress as discussed previously. The main goals of eating during training sessions and races during this phase are to prevent or reduce GI distress and recover nutritionally from high-intensity training sessions. From the previous training phase, you should have determined what food combinations work for you before your training sessions, and these should be carried over into this phase. Some of the meal and snack combinations that worked well in the previous phase may not work as well for higher-intensity training sessions. In some athletes, the gut becomes more sensitive during speed and power training. In this case, metabolically efficient meals and snacks should be consumed in liquid form, such as smoothies, 1 to 2 hours before a workout. This will normally decrease the risk of GI distress during a training session, although if you have a more sensitive stomach, try consuming a liquid source of calories about 3 hours before a workout.

Refueling the body after intense training sessions is important, but even more important is knowing when refueling is needed and when it is not. Recovery nutrition is not necessary after each of your training sessions. Replenishing glycogen stores is the main reason for following the scientific postworkout nutrition recommendations, with rehydrating a close second. However, keep in mind that glycogen stores can be replenished within 24 hours with just normal eating, so you may not need the extra calories from sport nutrition products after some of your training sessions. Here are some guidelines to follow for implementing a postworkout nutrition plan for training sessions longer than 4 hours or at high intensity for more than 90 minutes or for when you have a second workout that day or early the next morning.

Within 60 minutes after one of these workouts, consume 1.0 to 1.2 grams of carbohydrate per kilogram of body weight. This usually works out to 50 to 100 grams or 200 to 400 calories. Also, consume 6 to 20 grams of lean protein (essential amino acids). Be sure to minimize fat intake immediately after these training sessions because fat competes with carbohydrate absorption. After this initial feeding, it is then recommended to get back on track with your normal blood-sugar-controlling nutrition plan 2 to 4 hours afterward. On nonquality (not specific to race intensity or not specific to race duration) training days or even quality training days when you do not need to recover glycogen stores in under 24 hours, you can simply go back to following your normal daily nutrition plan.

For most triathletes, the off-season is a welcome time of year since it brings rest, recovery, and lack of structure. Unfortunately, it is also a time of year when triathletes make nutrition mistakes and see their body weight and body fat rise. Your primary nutrition goal in the off-season should be controlling the amount of food you eat by shifting the number of macronutrients you consume. You cannot eat the same way as you did in the previous training phase because you are no longer adhering to a training program and thus are not burning as many calories. The goal of controlling blood sugar is extremely important now, and focusing on eating lean protein, fruits, and vegetables as the mainstay of your daily nutrition is the main objective. Since you are not training, you do not need all the sport nutrition products you were using during your race season. Eliminate such supplements, and focus on controlling your blood sugar with real food.

Your daily carbohydrate intake should decrease to 3 to 4 grams per kilogram, with most of the emphasis on fruits and vegetables and less on whole grains and starches. Because of reduced energy expenditure, you do not need to eat as much carbohydrate as you did during your racing season. Protein intake should range from 1.6 to 2.0 grams per kilogram, while fat remains low at .8 to 1.0 gram per kilogram, with an emphasis on healthy omega-3 fats.

Eating during this phase is simple: You do not need to methodically plan as you did earlier during race season. Remember, you are exercising for fun now, possibly working on improving technique and recovering from your race season. Focus on being well nourished before exercise with a light, well-balanced meal or snack. During exercise, if you consume anything, it should be water, and don’t worry about following a specific postworkout nutrition plan. Eat a snack or plan a meal within 2 hours after a workout.

Table 26.1 summarizes the quantity and fluctuation of carbohydrate, protein, and fat throughout your annual training year.

Implement a year-round nutrition program in the same way as you plan a training program and reap the benefits of enhanced health, improved performance, and better body composition and weight control. Your eating program should ebb and flow just as your training does, and your physical performance will be much better supported when nutrition matches your physical training needs. Enjoy the journey of nutrition periodization and metabolic efficiency throughout your physical training phases.