O2max performance, or the athlete’s maximal pace and power for a 5-minute best-effort performance

O2max performance, or the athlete’s maximal pace and power for a 5-minute best-effort performanceTriathlon is a sport that people can do for a lifetime, so proper long-term development, regardless of when an athlete begins training and racing triathlons, is key to longevity in the sport. Long-term development is important for athletes to reach their potential and prevent performance plateaus, so triathletes must develop the proper skills and fitness in swimming, cycling, and running at the beginning of their triathlon training in order to be successful over the years. Within the discussion of long-term development, it’s essential to keep in mind the nature of the athlete. The vast majority of athletes do not require sophisticated planning and workout structuring; rather, they will benefit from a straightforward focus on the topics explored in this chapter.

There are building blocks of athletic performance that factor into athlete development. In order, these are as follows:

1. Movement skills and the ability to perform these skills quickly

2. Aerobic threshold stamina, known more commonly as endurance

3. Sport-specific strength, or the ability to apply force effectively

4. Lactate threshold stamina, or the maximum pace, power, or duration that an athlete can produce aerobically

5. Functional threshold performance, or the athlete’s performance for a 60-minute best-effort maximal performance

6.  O2max performance, or the athlete’s maximal pace and power for a 5-minute best-effort performance

O2max performance, or the athlete’s maximal pace and power for a 5-minute best-effort performance

These building blocks form a pyramid, where one block builds on the other. The first three building blocks provide the platform on which race-specific training is built. Consider these blocks the foundation for building a fit athlete. When an athlete’s skills break down, or the athlete fails to deliver training performance on race day, the cause is typically underdeveloped movement skills, stamina, and sport-specific strength. The final three building blocks are focused on creating a race-fit athlete who is prepared for competition at a specific event. Another way of looking at these two classes of fitness—athletic and race-specific—is this: The capacity to do work must be well established before an athlete will be able to absorb work-rate training. An effective mantra to remember is “Work before work rate.”

Performance Limiters

Performance LimitersWhen you train for a specific goal race, there will inevitably be factors that limit performance. For illustration, I have matched certain limiting concepts to each sport in triathlon, but bear in mind that all limiters can apply to any sport. (Later in this chapter, I outline specific workouts that can be used to assess, and address, an athlete’s current stage of development.)

Swimming is the most skill-dependent sport, and therefore, long-term development requires consistent training and a commitment to technical improvement. Although it makes sense to limit total time invested in swimming, for most of the year, it is essential to get the most from the time invested, because time is limited. Skills improve most quickly through workout frequency (practice) and informed video review (directed technical improvement). When skills are well established, triathletes have a mixture of strength and fitness which can help their swimming performance.

Understanding a swimmer’s pace versus duration curve, across distances of 50, 400, and 1,500 meters, will help the coach assess limiters, as will an understanding of an appropriate stroke for the swimmer’s body type and fitness. Smaller, and fitter, athletes should train to support a higher stroke rating (functional threshold fitness and movement skills will dominate how well they swim). Conversely, larger, and less fit, athletes should focus on distance per stroke (specific strength and movement skills will dominate how well they swim).

In terms of return on work, cycling is probably the fairest sport in triathlon. The skill component, and injury risk, is far less than in swimming, and running, respectively. Although body type has an influence on approach, far more important is understanding the specific performance and duration requirements of an athlete’s goal triathlon, both in terms of terrain and distance. The bike can, and should, be used to train for the entire duration of the triathlon (total time, swim–bike–run) as well as the specific duration on the bike leg (total distance, bike). For both these goals, an intimate understanding of the energy expenditure across the day (total) and per hour (rate) is required. Total work limiters are most classically seen in long-distance racing with larger athletes (e.g., moving 200 pounds across a 14-hour event requires considerable work, at any pace). Work-rate limiters are usually seen with experienced athletes, especially smaller and over shorter distances.

Typically, when we talk about fitness, we gravitate toward a work-rate discussion: the power or pace an athlete can produce. However, depending on athlete size, movement economy, metabolic efficiency, and event duration, the total output required for the event can be a fundamental performance limiter, most especially in amateur athlete populations. Put simply, many athletes, especially large and novice, build sufficient fitness to exhaust their fuel supply on race day. A fuel supply limiter can be identified, then addressed, on the bike—where work and work-rate information can be easily captured through the use of a power meter.

Long-term running development requires an athlete to run frequently for a long time. Athletes, particularly highly motivated triathletes, are often in a rush to get to “real” run training, or what they consider high-intensity running. Before embarking on a block of high-intensity training, consider if top-end sustained speed is truly limiting performance. Although athletes have an intrinsic attraction to painful training, in triathlon running, capacity to administer pain rarely limits performance. Instead, I recommend addressing the following:

Build connective tissue strength and address personal biomechanical limiters through frequent running, strengthening exercises (calf raises, hip bridges), and appropriate muscle tension (taut, rather than tight, muscles).

Build connective tissue strength and address personal biomechanical limiters through frequent running, strengthening exercises (calf raises, hip bridges), and appropriate muscle tension (taut, rather than tight, muscles).

Improve skills, and speed, in terms of movement economy, and quickness, respectively. Skills need to be learned in a low-stress, low-intensity environment and gradually progressed in terms of pace and stress.

Improve skills, and speed, in terms of movement economy, and quickness, respectively. Skills need to be learned in a low-stress, low-intensity environment and gradually progressed in terms of pace and stress.

Train the ability to operate efficiently in all the energy systems outlined in chapter 9, with a focus on progressive aerobic stamina. Most important, benchmark performance at, and slightly over, specific race pace. Assess race pace on actual, not goal, performances, and make sure the training program is rooted in reality.

Train the ability to operate efficiently in all the energy systems outlined in chapter 9, with a focus on progressive aerobic stamina. Most important, benchmark performance at, and slightly over, specific race pace. Assess race pace on actual, not goal, performances, and make sure the training program is rooted in reality.

Consider the role of body composition on overall performance. When body composition is limiting long-term development, total stress loads (training and life) should be reduced in order to create space for the athlete to build new habits. Be aware that endurance sports can feed the psychology of disordered eating, and seek professional medical help when needed.

Consider the role of body composition on overall performance. When body composition is limiting long-term development, total stress loads (training and life) should be reduced in order to create space for the athlete to build new habits. Be aware that endurance sports can feed the psychology of disordered eating, and seek professional medical help when needed.

By consistently applying a plan that is balanced between the three sports (swim, bike, run) as well as focused, primarily, on athlete-specific fitness, you will go a long way toward achieving your full athletic potential. As well, being committed to giving 110 percent in your training and competition can greatly increase the probability of success in the larger picture of your overall life.

To appropriately progress through these stages of development, you need to integrate techniques to improve your fitness. Consider the following five techniques as you strive to improve long-term fitness.

It is recommended that you follow a consistent, moderate training program for as long as you continue to improve. When plateaus are reached, it can be tempting to add to training load in an effort to improve. Although this is effective, in experienced athletic populations, improvement can come from varying the stress rather than increasing the stress. This technique is very important with fragile and injury-prone athletes.

Improvement takes time, and persisting across time requires motivation. Variation in approach within a season, and between seasons, is effective for maintaining motivation.

Triathletes in general, and working triathletes in particular, often lack the single-sport volume to make dramatic progress in any one area of their athletic portfolios. As well, it is far easier to sustain a higher performance level than reach a new performance level. Therefore, smart application of specific overload periods can take you to higher single-sport performance levels, which are maintained across your competitive season.

Athletes and coaches need to consider—and address—the attributes required for long-term success. Agility, flexibility, muscle balance, and maximal strength may not affect short-term performance, but their absence will impair long-term performance, particularly in veteran athletes. In the United States, the median age of triathletes is relatively high. Within adult populations, consider what will be required for athletic performance in 10, 20, and 30 years. Be very careful with training strategies that might mortgage future athletic performance. As a species, we share a weakness toward favoring the present over maximizing long-term returns.

For most triathletes, the greatest limiter to performance is stamina at appropriate race effort. Triathlon appeals to highly motivated athletes, and they often don’t want to do the training or put in the hard effort of the training required to develop superior strength and stamina. A coach can achieve a material increase in short-term performance by appealing to the athlete on a long-term development basis.

Although the previous techniques focus on developing your athletic abilities, keep in mind that your performance in a specific goal race—in all three triathlon events—also relies on a simple progression of improvement:

1. Completing the race distance across multiple days

2. Completing the race distance in a single day

3. Completing the race distance in a single day, without stopping

4. Completing the race distance in a single day, without stopping, and with pace changes designed to optimize finishing time (or position)

The steps in this progression should be addressed while you work on improving your economy, as well as the mental skills to optimize your race experience.

The best technique I know for constant athletic development is consistent repetition of a plan that is balanced between the swim, bike, and run and focused, primarily, on athlete-specific fitness.

In amateur athletic populations, plateaus frequently arise from a lack of consistent training load. Adding variability or intensity to an inconsistent athlete’s program is a distraction from what matters, which is establishing consistent training. The optimal strategy is to stay focused on a simple, balanced plan that removes habits and choices that impair your ability to do work. That said, what should this balanced plan focus on, and how can you assess your progress? To determine this, first consider these questions:

What is my stage of development right now?

What is my stage of development right now?

What are my goals?

What are my goals?

How much time do I have available for training?

How much time do I have available for training?

Does an increased focus on triathlon make sense for my overall life?

Does an increased focus on triathlon make sense for my overall life?

Make sure the answers to these questions are consistent and in harmony with your life. Before spending a lot of energy improving athletic performance, you need to ensure that triathlon fits within your overall life goals.

The following assessments allow you and your coach to examine your fitness, and they provide benchmarks for tracking improvement. Always consider benchmark performance relative to goal-race duration as well as goal-race performances. Moderate aerobic performances can be benchmarked daily. High-intensity and sustained best-effort performances need only be tested every 3 to 6 weeks.

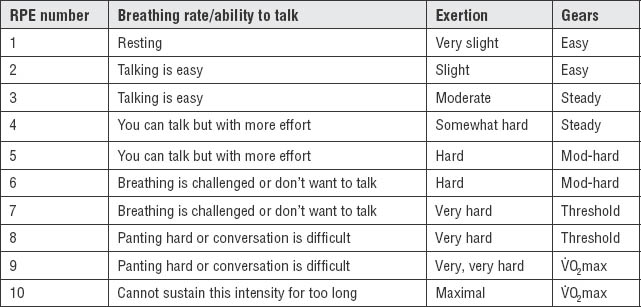

To help you out as you work through these assessments, consider that you have five gears within your aerobic engine:

1. Easy

2. Steady

3. Moderately hard (mod-hard)

4. Threshold

5.  O2max

O2max

These five gears correspond with the energy systems outlined in chapter 9 and are used to help you understand how intensely to perform each segment of these assessments.

This workout assesses athlete awareness of pace control and benchmark pace at different efforts. Swim this workout so it progresses from easy to max as the intervals progress. Although rest times of 10 and 15 seconds are noted, well-trained swimmers will achieve a more accurate assessment with rests of 5 and 10 seconds, respectively.

12 × 25 easy on 10 seconds’ rest

12 × 25 easy on 10 seconds’ rest

6 × 50 steady on 10 seconds’ rest

6 × 50 steady on 10 seconds’ rest

4 × 75 (25 easy, 25 mod-hard, 25 steady) on 10 seconds’ rest

4 × 75 (25 easy, 25 mod-hard, 25 steady) on 10 seconds’ rest

3 × 100 steady on 10 seconds’ rest

3 × 100 steady on 10 seconds’ rest

5 × 400 threshold on no more than 15 seconds’ rest

5 × 400 threshold on no more than 15 seconds’ rest

5 minutes easy

5 minutes easy

5 × 200 max on 10 seconds’ rest

5 × 200 max on 10 seconds’ rest

Cool-down

Cool-down

This workout assesses athlete awareness of pace control and benchmark pace at different efforts. Use the paces derived from assessment 1 to set the send-off (the time you leave for each interval) for each step of the main set (these are the sets of 200 in the workout). The longer main-set duration, and its sustained nature, will give an insight into your depth of swim fitness, or your capacity to hold pace over time. Well-trained swimmers will achieve a clearer benchmark by setting their send-offs based on expected pace for the final 200 and adding 10 seconds per set. For example, a fit athlete expecting to swim 2:40 for the final swim would set the send-offs at 3:20, 3:10, 3:00, 2:50, and 2:40, respectively, for the five 200s of the main set. Another way to complete this set is to take 10 seconds’ rest after each 200.

16 × 50, all on 10 seconds’ rest, with this pattern: 3 easy, 1 threshold, 1 steady, 1 modhard, 1 easy, 1 threshold (2×)

16 × 50, all on 10 seconds’ rest, with this pattern: 3 easy, 1 threshold, 1 steady, 1 modhard, 1 easy, 1 threshold (2×)

200 relaxed swimming, athlete’s choice,

200 relaxed swimming, athlete’s choice,

5 × 200 easy on 10 seconds’ rest

5 × 200 easy on 10 seconds’ rest

4 × 200 steady on 10 seconds’ rest

4 × 200 steady on 10 seconds’ rest

3 × 200 mod-hard on 10 seconds’ rest

3 × 200 mod-hard on 10 seconds’ rest

2 × 200 threshold on 10 seconds’ rest

2 × 200 threshold on 10 seconds’ rest

200

200  O2max

O2max

Cool-down

Cool-down

This workout assesses an athlete’s ability to hold aerobic paces over long durations. Use pace data from the previous benchmarking swim workouts to set goal paces. Until you have sufficient endurance for a total swim distance of 5,000 meters, adjust the swim interval distance by using 400s, 600s, or 800s. Most athletes should aim to move from easy to moderately hard paces. Well-trained swimmers will be able to move from easy to threshold paces.

5 × 1,000, descending 1 to 5 on 15 seconds’ rest:

5 × 1,000, descending 1 to 5 on 15 seconds’ rest:

• 1st 1,000: moderate pace, with 15 seconds’ rest

• 2nd 1,000: faster than the first 1,000, with 15 seconds’ rest

• 3rd 1,000: faster than the second 1,000, with 15 seconds’ rest

• 4th 1,000: faster than the third 1,000, with 15 seconds’ rest

• 5th 1,000: faster than the fourth 1,000, with 15 seconds’ rest

An alternative structure, where pace is increased on each set, can be used for this assessment as follows:

10 × 100 on 5 seconds’ rest

10 × 100 on 5 seconds’ rest

8 × 125 on 10 seconds’ rest

8 × 125 on 10 seconds’ rest

4 × 250 on 15 seconds’ rest

4 × 250 on 15 seconds’ rest

2 × 500 on 20 seconds’ rest

2 × 500 on 20 seconds’ rest

The previous three swim workouts assess pace and the capacity to hold pace over time. This workout lets you see how long you can sustain threshold paces and higher. To assess this, the total main-set duration should be 40 to 60 minutes long. Use a fixed send-off that is slightly longer than threshold pace. For example, if threshold pace is 1:27 per 100, then a send-off of 1:30 would be appropriate, and the main-set structure could be 30 × 100, holding on 1:27 and leaving on 1:30. Note that most athletes overestimate their speed at threshold and use a pace that is closer to velocity at  O2max. If you are seeking to train

O2max. If you are seeking to train  O2max pace, then use a main set of 12 to 30 minutes’ duration, with rest intervals of between 35 and 100 percent of work intervals. For example, if

O2max pace, then use a main set of 12 to 30 minutes’ duration, with rest intervals of between 35 and 100 percent of work intervals. For example, if  O2max pace is 1:20 per 100, then an appropriate main-set structure would be 12 × 100, leaving on 1:40 and coming in on 1:20.

O2max pace is 1:20 per 100, then an appropriate main-set structure would be 12 × 100, leaving on 1:40 and coming in on 1:20.

500 easy on 20 seconds’ rest

500 easy on 20 seconds’ rest

4 × 100 descend on 15 seconds’ rest

4 × 100 descend on 15 seconds’ rest

4 × 75 (as 25 build, 25 steady, 25 easy) on 10 seconds’ rest

4 × 75 (as 25 build, 25 steady, 25 easy) on 10 seconds’ rest

4 × 50 threshold on 15 seconds’ rest

4 × 50 threshold on 15 seconds’ rest

100 easy

100 easy

12-40 × 100 with prescribed pace and rest

12-40 × 100 with prescribed pace and rest

Cool-down

Cool-down

The goal of this workout is to assess aerobic range as well as top-end performance. The test can be done maximally or submaximally. If you do not have access to a power meter or other power measuring device, then the best way to do this test is to start 10 beats per minute below the bottom of your steady heart rate zone and track distance per step. Use 5 beats per minute as your step height, and continue until one step past functional threshold heart rate (FTHR).

First, you’ll need a rough estimate of your functional threshold power (FTP), and then you warm up for 20 to 30 minutes, with your power remaining under 50 percent of FTP. The actual test should start at 50 percent of FTP. This is a very easy intensity on purpose. To get a clear reading of your aerobic zones and break points, you need to start quite low. The most common mistake in benchmarking is a fast start because it skews the data.

If your FTP is less than 125 watts, then use 10-watt steps; from 125 to 174 watts, use 15-watt steps; from 175 to 249 watts, use 20-watt steps; from 250 to 349 watts, use 25-watt steps; and for 350 watts, use 30-watt steps. Be aware that step height is another area where you can skew your data. If the step heights are too large, then you could pass right through an important break point or training zone. So it is better to use smaller steps if you are unsure.

When performing the test, each step should last for 5 minutes. Record your heart rate at 1-minute intervals. The main things you want to track are heart rate, power, and effort (how it feels)—these are most important within your likely race power range. How far you progress will depend on you. There are benefits of taking the test all the way to failure (checking for fatigue and seeing top-end heart rates); however, these aspects do not need to be tested often. If you plan on doing the test often, then you need only go to failure once per quarter. The rest of the time, build to slightly past FTP.

The goal of this test is to assess your progression over longer durations. If you have a power meter, then this workout will let you check on your power zones. If you don’t have a power meter, then you can still test by benchmarking distance traveled for each segment of the test set. Rather than fixed times, you can use a fixed-distance course and note your split. It’s not perfect, but on a calm day, your average speed will be a meaningful number.

The warm-up should be about 45 minutes; include about 15 minutes of steady effort as well as some 4 × 2-minute builds where you lift effort gradually from steady to just under functional threshold (effort, not HR). Spin easy between the warm-up intervals. The main set is a 45-minute continuous effort split into thirds. Aim for 15 minutes’ worth of effort at each of aerobic threshold (AeT, bottom of steady), lactate threshold (LT, top of mod-hard), and functional threshold (FT, top of threshold). A 45-minute main set is a short test for an endurance athlete—races and long workouts will let you see how much you decouple (during a race, or long workout, how far away from your benchmark tests are you performing?). When endurance is well established, you should be able to stay within 7 percent of these benchmarks when racing as well as in your long workouts.

Another way to approach the test is to benchmark off a target heart rate. Use the HR that corresponds with aerobic threshold, lactate threshold, and functional threshold, respectively. Give yourself 5 minutes to gradually build to each target HR. If you don’t have access to a power meter, then use the target HR method and track distance covered. Although distance is influenced by wind speed and direction, you will still be able to gather useful data. These field data are useful for comparison against progressive bike sets that are often done in the lab or indoors.

The goal of this workout is to assess the depth of aerobic stamina over race durations as well as the impact of periods of higher intensity. To perform the test, start with 10 minutes at easy pace, then move into a 2-hour continuous main set where you alternate 40 minutes of steady effort with 20 minutes of mod-hard effort. Finish with 5 minutes of easy cycling, and then go into your run.

Another option is to start with 10 minutes at easy pace and then move into a 2-hour continuous main set, where the first hour is 40 minutes of steady effort and 20 minutes of mod-hard effort. For the second hour, start with 20 minutes of steady effort, and then do 10 minutes of mod-hard effort; for the final 30 minutes, progress in 10-minute blocks from steady to mod-hard to threshold effort. Immediately after the threshold block, insert 20 minutes at steady effort—bring your heart rate down gradually while spinning slightly faster than normal time-trial cadence.

The goal of this workout is to assess aerobic range as well as top-end performance. The test can be done maximally or submaximally. Perform this test at a track; one lap = 400 meters or one-quarter of a mile, and the total test distance is 10 to 12 kilometers (continuous).

To perform the test, warm up with 15 to 20 minutes of recovery-effort running or cycling. Run increasing 2,000-meter repeats. Start the first 2K at 20 beats per minute (bpm) below the bottom of your steady zone, and increase effort by 10 bpm for each successive 2K interval. Track your average pace and maximum and average HR for each 1,000-meter leg, and continue until 2K beyond functional threshold heart rate.

Note that if you have access to lactate testing, then you can take lactates at the end of each 2K stage. If you are taking lactates, the baseline lactate (before starting the test) needs to be under 1.5 millimoles. If lactate is elevated, then continue an easy warm-up for a further 10 minutes and test again. If still over 1.5 millimoles, you’ll have to try another time to achieve accurate lactate values. If most of your steps would take longer than 10 minutes, drop the interval duration to 1,600 meters. If most of your steps would take longer than 12 minutes, drop the interval duration to 1,200 meters.

The goal of this workout is to assess progression over longer durations. This workout is best done in the field rather than on a treadmill or track. Choose a course you can easily access. The precise durations are not all that important; when doing this session myself, I use a trail around a small local lake.

To perform this test, think about this set as 5 × 12 minutes, as follows:

12 minutes easy

12 minutes easy

12 minutes steady

12 minutes steady

12 minutes mod-hard

12 minutes mod-hard

12 minutes threshold

12 minutes threshold

12 minutes steady

12 minutes steady

End with strides

End with strides

Note that you can extend the duration of the final steady block to assess decoupling (explained in bike assessment 2). For a long benchmarking workout, repeat the main set twice. Use effort the first time through the main set, and use heart rate the second time. Compare the average pace achieved with the two methods to assess the accuracy of your pace perception.

This chapter has been written assuming a goal of developing athletic performance. In fact, it was my mission to share what I’ve learned on this subject with you. However, in my years of coaching, training strategy rarely limits performance.

Most athletes are driven by something other than race-day performance, and the value in athletics flows from an area other than the finish line. When building a long-term plan, coaches and athletes should consider all areas of personal and athletic development: performance relative to others, performance relative to self, long-term personal health and longevity, and life skills learned through athletics.

Even with elite sport, the value of competition comes from its ability to increase an athlete’s drive to be the very best he can be. In learning to maximize your ultimate athletic potential, you will learn valuable skills you can apply to your life long after you are finished competing in sport.