We’d seen them often enough, the goods trains with a carriage tagged on, just in front of the trailing guard’s van. Sometimes you’d see a handful of faces at the old carriage windows as the goods train went ambling past, across the level crossing and out of town.

There was always a lot of noise associated with such trains. Empty wagons banged as if a panel beater was trapped inside, livestock bleated in sheep wagons heading for the works and there was always a wagon with a wonky wheel and a protrusion dragging in the ballast, sending out sparks and the sound of metal on metal.

The slower the train went, the more noise it made. Or the greater the chance for observers to hear the clatter. A fast goods train, like the goods express, barely seemed to touch the rails as it sped through town. It didn’t stop much and was able to maintain a fast clip.

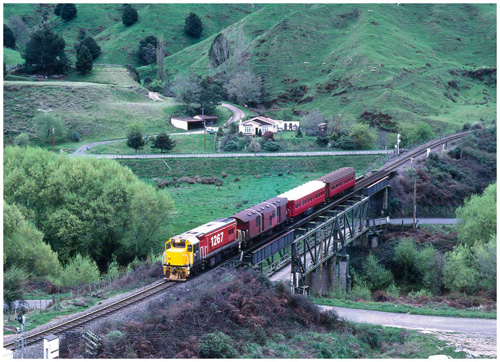

In the steam era the ‘goods train with a carriage’ was more prevalent, but they were still running when DA diesels stepped up. We travelled on one the day we needed to get to Taumarunui to watch a rep rugby match. That was the 443 Te Kuiti to Taumarunui mixed train on the main trunk – a classic, apparently, of its genre.

‘Mixed trains’ were usually defined as ‘goods with car,’ sometimes there were also ‘mixed goods’ and our own ‘goods train with a carriage’ widened the definition base. There were many of them running between intermediate stops on most lines – and back in the day they were as common as dirt and as cheap as chips, but they got you where you wanted to go, beyond the orbit of long-distance expresses, limiteds and railcars. Once the latter had sped between larger towns and cities, leaving rural locals gasping, the ‘mixed’ would come along, do a bit of time-consuming shunting, wait interminably for opposing traffic to enter passing loops and carry heartland folk at a doddle to somewhere down the line.

From Te Kuiti you could get to Frankton by mixed train, as well as by the Taumarunui service, but the day someone suggested you could catch a mixed train from Taumarunui to Stratford along the Stratford to Okahukura branch line, we tended to disagree.

David Leitch wrote an excellent hardback called simply Railways of New Zealand. It was published in 1972, after we’d undertaken two rail odysseys in 1967 and 1971, and had come home flushed with an awareness we’d broken the back of the New Zealand Rail skeleton. Leitch alerted us to the fact there were other lines and passenger services still available to rail aficionados.

The Stratford to Okahukura line was one. It ran a backwater course from Taumarunui to Stratford and played host to the Auckland to New Plymouth railcar, goods trains – and the 542, a meandering daylight ‘mixed’ which took most of the day to get through the 24 tunnels along 143 kilometres of remote and rugged backblocks.

The third of our rail odysseys occurred in 1975–76, after I’d recovered from preoccupation with marriage, overseas travel and other diversions. Part of our honeymoon included travelling around Northland on those ‘mixed’ trains which were still running. We were able to thread the needle between Auckland Central and Helensville and travel between Maungaturoto, Whangarei and Opua, all by Northland ‘mixed’ trains. Someone had traced ‘silver star’ in the window dust of one of the trains, which pointed up a certain run-down, ironic aspect.

As interesting as those ‘mixed’ journeys were, one much closer to home was to become the jewel in the crown: the mixed train between Taumarunui and Stratford. On a hot summer’s day in 1975, within cooee of its final foray, with its lone wooden carriage occupied by five intrepid travellers, four of whom hadn’t previously known the train existed, number 542 was in its element. We had been only vaguely aware there was such a serpentine line spreading so far through a narrow neck of New Zealand that was also little known.

We’d always thought the railcar which passed through Te Kuiti at 4 o’clock in the afternoon was on its way to Wellington. Even when the major flood of 1958 forced several trains – including the New Plymouth to Auckland service – to cool their heels in Te Kuiti, it didn’t occur to us that the train from New Plymouth could have made its way to our backyard along a branch that was closer to home.

Finally someone checked the New Zealand Atlas. Sure enough, just north of Taumarunui at a place called Okahukura Junction, a line branched off the main trunk, heading west. We may have already seen the branch line arcing over a roadrail bridge across the Ongarue River, while travelling on the main trunk ‘mixed’ between Te Kuiti and Taumarunui, but it probably looked like one of the bush tramways, common in the bush-clad hinterland. On the way back from Taumarunui, with the late afternoon sun shafting its light through the grimy carriage window, our vision was probably impaired. We were otherwise occupied, drinking our first-ever bottle of beer to celebrate King Country’s rugby win. And any other excuse for a shared, frothy, teeth-clunking swig.

In those days, there wasn’t the burning hunger to know where any off-shoot branch line went. Not initially. We were quite happy to trundle up and down the main trunk, because that was the line that went through Te Kuiti.

Even when my friend Russ rhapsodised about the Northland Line, the Opua Express and the Taneatua Express on the Bay of Plenty line, we figured he might have been making some of it up, even though it was common knowledge that Russ and his family took their summer holidays in the Bay of Islands and Tauranga. And they went by train. At the time we had a certain landlocked mentality. Not even when Mike Walker from Ohura, a coal-mining town we knew was located in the backblocks way off the main highway and main trunk, said he came into Te Kuiti by railcar to visit his grandparents in the weekend, did we twig to the notion of another line out there somewhere. We had always assumed Mike went by bus to Taumarunui and utilised the main trunk.

But now David Leitch and the New Zealand Atlas had confirmed it – an inland Taumarunui to Stratford line, with passenger trains running along its course. One of them was the 4 o’clock Auckland–New Plymouth railcar. Without further ado I booked a seat.

Winter fell suddenly at that time of year. Fog drift accompanied us, and by Taumarunui it was getting darker. Then the railcar returned back up the main trunk until, at Okahukura, it curved westwards across the Ongarue River and disappeared into a world of enveloping blackness on the Okahukura–Stratford line and on to New Plymouth.

It’s a most unlikely railway line, in an unusual setting, which is why its existence wasn’t well known. The region features no large towns, nor remarkable natural phenomena, such as exploding volcanoes or massive waterfalls. Large towns were supposed to burgeon because of the presence of the railway line, or small ones at least become sizeable agriculture service settlements once the railway had stimulated the growth of farms and the breaking in of the land. But the bush won out and settlers continued to leave the backblocks, even after the line was opened.

After my railcar trip on the branch line – one that was shrouded by night – I felt there was some urgency to take the last available day train, which was the mixed goods with a carriage, from Taumarunui to Stratford. Passenger services were being cut back in several regions and I couldn’t help but feel that the SOL – the common vernacular for the Stratford–Okahukura Line – would also be affected.

Destiny was on our side the day a group of us travelled on train number 542, the ‘mixed’ service from Taumarunui to Stratford. From one backwater to another through a New Zealand rail wilderness. We had no way of knowing the urgency of the situation when we climbed aboard the mix-and-match service – humans travelled on the same train with sheep and cattle, although not in the same wagon. It all seemed perfectly laid back on a fine, breezy early November morning. No urgency there. The ticket seller at Taumarunui seemed hung-over and ham-fisted as he scrambled around for the appropriate ticket book for the SOL.

Our train sat throbbing patiently as the official departure time of 8.55am came and went. Obviously no urgency there either.

‘Why 8.55am? Why not round it up to 9 o’clock?’ Harry’s comment seemed reasonable but it elicited no response from the ticket seller, who couldn’t seem to get his ticket stamper to work. ‘That’s why they don’t say 9 o’clock. The ticket man needs five minutes to fire up his stamper.’ It seemed a reasonable comment.

The driver of DA diesel 1518 looked anything but urgent as he swung himself up on the cute little stairs at the front of the engine and accessed the protruding cabin with a pie between his teeth. At 9.10am. We thought we’d better swing aboard too, despite the laid-back nature of our departure.

Eight fifty-five indeed. Mind you, the ticket seller was so nonplussed by five humans wanting to travel on 542 you figured it could be up and gone before you knew it.

‘How many passengers do you normally get?’ Russ asked.

‘We normally get nil, sir.’

‘But there appears to be a human form, sitting in the carriage. That’s one more than none.’ Russ was right. There was a sullen outline of a young man’s face peering from a carriage window.

‘Well, if that’s the case, he hasn’t bothered to buy a ticket,’ the ticket seller replied. ‘Good luck to him, but the guard needs to punch something. If it’s not a ticket it might be his lights. It’s happened before.’

‘You mean if he’s got no ticket the guard will punch his lights out?’

‘Barney has his own way of doing things.’

We broke into a bit of a jog as we sought out the carriage at the rear of the train, a bit more urgency creeping in. Didn’t want to upset Barney by holding up the train. The carriage, AA 1071, was one of those old wooden jobs last seen on the main trunk express back in the ’30s. It had an open-air platform at each end and was surprisingly spick and span for a service that was hardly ever used. The urgency died as we realised we had the carriage to ourselves. The sullen-faced young man had disappeared.

We all found window seats. Russ and Julia opted to sit facing each other and were able to facilitate such positioning by manhandling the stiff, rotatable red leather seats into a one-on-one situation. Russ remembered he didn’t like travelling backwards. It made him disoriented and light-headed. So Julia stepped up and crossed over. Harry spent his pre-departure time adjusting light-levels and focusing his movie camera, to take into account the carriage murkiness. I applied a blast of antihistamine spray to keep my hay fever at bay.

Which brought us back to the urgency issue. Back in 1975 when seasons were more predictable, November was the time in early summer when the cruel irritants of seeding grasses, pine dust, privet and honeysuckle pollen filled the air and set half the nation sneezing. November was also the month we had planned the rail trip on one of the least known and certainly unsung rambles into the middle of nowhere. You had to be more than a rail buff to catch this train. It was almost a case of calling all social historians ... and perhaps the odd archaeologist.

We travelled in early November, 1975 and on 28 November of the same year the last train to Stratford ran. The mixed goods, number 542, was no more. That was where the urgency came into it. Another week or two and we would have missed out. Beyond 28 November the ticket seller might have still groped around for his ticket book and stamper, but there would be no ancient wooden carriage slung on as an afterthought next to the guard’s van. And no passengers needing tickets.

It was several years before we realised the closeness of the call. Once we’d sneezed and breezed our way through the inland Taranaki route to Stratford, we moved on. Generally we began looking outward, which meant seeking out the newer trains – mainly main trunk developments – or heading overseas.

There were many memories associated with train 542 but the true character of the mixed train was also in evidence. One stark memory in the semi-dark summed up the indifference and confusion associated with mixed trains in their death throes. If the ticket seller at Taumarunui, Barney the guard, and the driver of DA 1518, who may still have that pie between his teeth, were throwbacks to a prehistoric time, they were laid back compared with the shunter at Maungaturoto when we travelled by mixed train through Northland.

Apparently the mixed train from Maungaturoto to Wellsford was curtailed in 1967, yet as we climbed down at the end of the line for the Whangarei to Maungaturoto mixed in 1975, a local shunter with beer on his breath and a large flashlight, operated with a certain urgency.

‘Hurry up folks, this carriage has to be back in Wellsford as soon as possible,’ he yelled.

It was all a bit mysterious. If the Maungaturoto to Wellsford mixed no longer ran why did the carriage have to be back at Wellsford as soon as possible? It was a lingering memory, the sight of the shunt gathering speed in the Northland night, taillights glowing in the gathering gloom as the train bounced over the rough track. Such was the pace of the retreat you had to question the need for such speed. Perhaps urgency means different things in different corners of the country.

The diesel pulling the Taumarunui–Stratford train sounded urgent enough as it growled into action, sounding its horn several times to ensure the town was awake. It took a surprisingly long time to travel up the main trunk to the junction at Okahukura – one of those lonely, one-horse stops in the middle of nowhere. Waiotira Junction in Northland, where the Dargaville line branches off the main north line, is another. Often rail junctions develop into sizeable settlements, but Okahukura was never more than a station, perhaps a railway house or two and maybe a garage.

We waited for a main line goods to clear the points before heading out to the west, across the Okahukura road-rail bridge and into unseen territory. It’s interesting to contemplate the historical notion of travelling by trains which could only go as far as the line extended at any given point in time. In 1926 trains started running from Okahukura to Ohura, because that was how far the line extended from the east. From the other end – the Stratford starting point – work on the line began in the early 1900s. In 1975, for some reason you half-expected the train to reach its terminus beyond the first tunnel and just around the next bend.

The trip from Taumarunui to Stratford was a step into the past. This was how Kiwi train travellers got around in days gone by. From town to country, general store to farm, community hall to the ‘pictures,’ accident site to hospital. They said the railways opened up the land. With the SOL that maxim prevailed to a certain extent, but much of the land remained isolated despite the rail.

As we passed Matiere the hills were already dominating the landscape. This was a frontier railway, New Zealand style. We felt like extras in a train robbery movie. In the movie Harry made of the trip we are all at some stage captured sauntering down the carriage aisle like Gary Cooper entering the Dry Gulch saloon. Everything seemed to play out in slow motion and ’70s sepia.

The mixed goods was also like travelling on a time machine. This was part of our history and we had been offered a rare opportunity to taste the past. This was no vintage rail experience with all the bit-players dressed self-consciously in period costumes. This was the real thing. The guard was dressed up as a real guard. His uniform was traditional NZ rail sandpaper and trim. He was even good old-fashioned grumpy as he wandered through the carriage to check our tickets.

‘Weren’t there six of you?’ he asked through lips that didn’t move much.

‘There may have been another guy, but he seems to have gone now. Perhaps he got off.’ My reply went unchallenged as the train approached Ohura, a settlement which looked positively urban after all that rural wilderness. At Ohura the summer heat shimmered on the corrugated iron roofs. The sun, finding a gap in the hills and clouds, assaulted the skin. Long hair and beards served a purpose – they kept out the recently discovered suspect rays piercing through the hole in the ozone layer. The train waited. The engine throbbed. The shimmering heat from the diesel’s exhaust matched that of the Ohura roofs.

Still the train waited. The guard ambled through the ballast, kicking vaguely at something beneath a couple of sheep wagons. Ours was a long train and it took the guard as long as it takes a guard to walk the length of a long train to get back to his van. He didn’t look up in recognition of our presence. He just clumped in his sandpaper uniform through the time warp we had invaded.

Our carriage was a bit of an afterthought anyway. It was a dislocated vessel that didn’t seem to be part of the train. If it derailed in Tangarakau Gorge and disappeared into the undergrowth no one would come looking for it for weeks. Perhaps that had already happened and fellow rare-as-hens’teeth passengers were probably adapting as we spoke to life in an abandoned wooden carriage. Living off the land, tickling trout in the Ohura River, trying to eke out an existence, aware the search parties weren’t coming.

Somewhere along the line – it may have been at Mangaparo – a short distance on from Ohura, our train switched to the passing loop. Ten minutes later the New Plymouth to Taumarunui railcar crept past on the main line. The railcar was half full, the most people we had seen in one place all day. Most were dressed conservatively. Perhaps some were off to a wedding or a funeral. By comparison, we looked like a bunch of folk singers.

Travelling on 542 on the SOL was a pretty folksy thing to do. At a time when young, once-urban tribes took to the backroads, decrying the city, to find ‘paradise’ in rural communes, trains like 542 seemed to honour retreatist behaviour. Certainly we saw some interesting old homesteads and peeling villas, abandoned and standing sentinel on lonely hilltops, waiting to be salvaged. No one would hassle you there. No city fathers, worried mothers, short-haired rednecks or trilling Presbyterian sisters. And 542 – Old Faithful – would remind you of the outside world and provide transport to town if you needed new guitar strings and other provisions.

We felt as if we were acting in New Zealand’s equivalent of ‘Easy Rider’, with a mixed train substituting for Harley Davidsons. There was definitely something funky and alternative about our modus operandi and mode of transport as we continued to retreat.

Mind you, anyone could dream back then. I may have called it funky, but others called the service run-down. In the modern era 542 may not have been grand, but it remained redolent of something sacred: a transport hub which helped create the New Zealand we know. A museum on wheels, if you will.

Meanwhile the motor car had taken over. Not only did it kill, it hastened the isolation of Kiwi from Kiwi, with the kids in the back and Nana in the boot. In the days when trains ruled the transport roost people mingled – in carriages, on station platforms, in refreshment rooms. Mind you, the sullen-faced young man – the sixth passenger – hadn’t mingled. At Tokirima he snuck out of the toilet, swung down into the long grass and disappeared from sight.

Talk is cheap. As the train continued to be delayed at Tokirima youthful self-expression did the rounds. Someone reckoned 542 was the drop-out express. And New Zealand railways of the ’60s and ’70s had become part of the anti-establishment expression. While many other young Kiwis adopted the rule of thumb, hitchhiking to freedom-come, or invested in battered panel vans fit for 20 drop-outs, or purchased strange, cheap brands of car like ancient Jaguars, Citroens, Rovers or Vanguards, we expressed our individuality by travelling on as many trains as we could find. The sense of adventure and freedom was profound, as was the ability of trains to throw up companions amongst fellow travellers. Besides, trains often went where roads didn’t.

It was a time to dream but as the train went through the Tangarakau Gorge, a ruggedly beautiful stretch, it was appropriate to remember the hard times when the line was constructed. The construction camp of Tangarakau was the only one in New Zealand that wasn’t closed down during the Great Depression. Perhaps the bureaucrats forgot about the hard workers, beavering away at the rugged ramparts in the misty backblocks.

Others – dreamers – liked to think there was something mystical and intangible about the line. Something else was guiding its progress, but in reality it was probably the fact that there were fewer than 32 kilometres to go, to link the western line with the eastern equivalent, that saved the Tangarakau work camp. But for that timely connection, the line may have petered out into two branch lines, and then died altogether.

My hay fever was relentless as the line headed for Whangamomona. Honeysuckle, privet and diesel fumes impacted while the train was in the 24 tunnels and my plight called for another antihistamine.

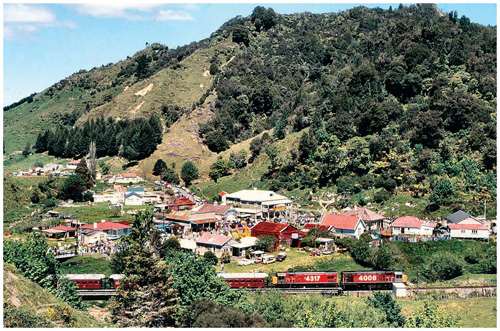

Whangamomona. The very name captured the imagination. The town was nestled in a narrow valley. An old green weatherboard hotel stood vigil over a couple of grimy garages, a garish general store and a shoe-box post office. A deep stream surged out of the dense native bush and skirted the collection of railway houses where washing drooped from improvised clotheslines. A mechanic in overalls disregarded the train as he wandered over the road towards the pub. He appeared to be Whangamomona’s sole occupant.

I knew of a guy who lived in the back of Whangamomona. I didn’t know him that well. Besides, how could anyone live in the back of Whangamomona? This was the back. Surely the universe came to a clanking halt against its valley walls?

My travelling companions were interested in the guy from the back of Whangamomona. Did he have two heads? They bet he had facial hair to sink a ship. He was probably decked out in lightly-cured animal-skin garments made from bush varmints, that gave off pungent odours to signal his emergence from the dense undergrowth at the edge of the world. After all, the further you travelled into inland Taranaki – New Zealand’s ‘Deliverance’ backwater, the more likely you were to stumble upon folk who acted out the roles of Ronald Hugh Morrieson characters. Where the bush was as dense as Satan’s beard, folks had supped too long at an ever-shallowing gene pool and outsiders had better be wary.

Yet Ben McDonald, the guy I knew slightly and played rugby against, was as clean-cut as Vic Damone or Paul McCartney after a trip to the barber. Open-faced and more friendly than most country boys. That seemed to be a relief to some as 542 finally headed towards Stratford. It wouldn’t do to have hippy drop-outs sharing the wilderness with rednecks.

Late afternoon. No more sneezing. More snoozing, if anything. Coming out of the ‘wops’, down from the hills. Te Wera, Huiroa, Douglas, Toko. We’re on the dairy flats now and Egmont is dominating the skyline. Finally 542 from Taumarunui clatters into Stratford yard, people uncoil and I start sneezing again.

The train stops with several lurches, followed by a loud crash, as all the energy from the domino effect between the wagons concentrates on the rear vehicles. If it’s bad for us it must be worse for the guard in the van behind.

We all experienced a weird feeling of triumph as we climbed down from the train when it finally came to a rest on a Stratford shunting line, about four adrift from the platform. This wasn’t like swaggering into Auckland Station at the end of an express run. There wasn’t a soul around. The guard had gone. Had he already been made surplus to requirements? The need for guard’s vans – and guards – was already being discussed. The engine still throbbed but the driver and fireman had scarpered. Then the engine began making irregular, coughing sounds. Did it have hay fever too?

It was an eerie, if triumphant setting. We had conquered a unique Kiwi train journey through a territory of which many would be unaware. Certainly not those of our cohort who had gone fishing for birds and spent the day trying to look very important on some Bay of Plenty beach with very few clothes, and now retreated to holiday tents with blistered backs, throbbing temples and empty sleeping bags. And if the birds weren’t biting, the mozzies soon were.

Our triumphant feeling was tempered by the pain of stepping on flint-hard ballast stones, which defied our flapping jandals. We had to scramble over four heaps before we were able to clamber up onto the Stratford Station platform.

My sister and her husband picked us up. They lived at New Plymouth and had to go out of their way to meet this odd train coming out of inland Taranaki, for no other purpose than to transport a few head of sheep – and humans – a bit of timber, a little lime, some empty LC wagons, a tractor tethered to an LA, a grumpy guard, a fireman and a DA driver with a perpetual pie between his teeth, to a rendezvous with the main Taranaki line.

‘Why didn’t it go all the way through to New Plymouth?’ my brother-in-law asked.

‘I think some of the timber had to go south,’ I replied. ‘No point taking it north and then turning it around to go back over the same tracks.’

‘Yeah, but if it was a passenger train wouldn’t it make sense to run through to the biggest place, New Plymouth?’

‘It doesn’t normally have passengers.’

‘But it had a carriage – and you bludgers.’

‘True.’

My brother-in-law, an Australian, shook his head, realising New Zealanders did things differently, probably because we lacked a sense of urgency.

As we bunked down at my sister’s place and tucked into industrial-strength baked beans from catering-sized cans and fillets of a good-sized snapper caught off the rocks that day, no one spoke much about the day’s rail adventure. Not because it wasn’t momentous or memorable, a blast from the past, a slice of true Kiwiana ... but because we were all in.

The journey from Taumarunui to Stratford wasn’t like a casual one-way fare from Te Kuiti to Auckland on the express or railcar. For a start it passed through territory we’d never seen before. Certainly not from the railway’s perspective. All our senses were on high, and I had my hay fever to contend with. Antihistamines can wear you out. Apparently I sneezed 129 times between Te Wera and Douglas, before the medication kicked in.

As I drifted off at 9pm the images from a remarkable train ride washed over my subconscious: 24 tunnels bisecting green razorbacks; scrubby foothills; barely a town of any size. Hardly a fellow human. The 24 tunnels. You’d barely get a tunnel on our usual rail drag between Te Kuiti and Auckland. The Purewa Tunnel perhaps, or the Parnell if you were routed the other way. Honeysuckle vines dangling over the train, releasing their hay fever-inciting pollen. Standing for hours on the outside carriage platform, watching the lengths of timber swaying in the next wagon and allowing the rush of air to keep you cool. How cool was that? I thought we looked extremely cool, more so than our long-haired contemporaries sweating it out at a rock concert or twisting and shouting around a driftwood fire at the Mount, or some similar beach populated by those with a strong herding instinct.

After travelling on the SOL it was hard not to feel a bit smug about not only discovering the obscure route (the accompanying road is known these days as the Forgotten Highway), but actually travelling down it on one of the last mixed trains. A priceless link with the past was severed, but not before we’d savoured it. How many others could say they’d even heard of the inland Taranaki passage, let alone travelled on it?

My mother-in-law was someone who could lay claim to both. An infrequent train traveller, she’d taken the Taneatua Express a number of times, caught the overnight express from Hamilton to Wellington once – and on another occasion when she was invited to a 21st birthday party at Huiroa, she ended up travelling on the SOL. Huiroa is a few kilometres inland from Stratford and is located right on the line, in an area, between Te Wera and Douglas, where the highway and railway line part company. To get there from her home in Whakatane she utilised the Taneatua Express from Whakatane West all the way to Frankton Junction on the main trunk, where she had a long wait until the Auckland to New Plymouth night express arrived at 10.16pm. After transferring to the SOL at some ungodly hour, her train would have pulled into Huiroa a little before six in the morning.

She’d stolen my thunder.

Everyone’s thunder was stolen in terms of train 542 and its sister ship going the other way, 529, when the passenger accommodation was taken off. Typically there were no passengers to commemorate the occasion, not even a sullen-faced youth or two. Slogans had been chalked on the side of the carriage. At least someone was aware of history receding down the line. ‘The last farewell’ festooned the final carriage – A1563 for the purists. The two DA locomotives used in tandem both ways were numbers 1505 and 1508.

We’d snuck in, but only just, and travelled on a New Zealand classic to which even my mother-in-law couldn’t lay claim.

Postscript

In more recent years someone else discovered the SOL – and Whangamomona. Well-patronised trains descended on the town from both the eastern and western approaches, to help the locals (both of them someone reckoned) celebrate the Republic of Whangamomona Day. For several years the tiny hamlet was engorged by train lovers, country and western singers and fans, general friends of the back of beyond, rootin’ tootin’ shootin’ types, and those who liked to say they’d been somewhere they’d never been before.

What happened on some of the homeward-bound trains has become part of New Zealand railways folklore.