The Northern Explorer sounded a bit like one of those old paddle steamers Humphrey Bogart might have steered up the Congo in best African Queen tradition. It also sounded like the name of a new main trunk train plying the principal route of the North Island, New Zealand. A name with connotations of the Northerner and Overlander, two recent long-distance trains connecting Auckland with Wellington – one by day, the other by night.

The Northerner completed its tour of duty in 2004. There were no more night trains after that. The Overlander was lucky to survive as long as it did. Perhaps that was why there was little kerfuffle when the final demise of the Overlander was announced. Supporters were weary of the fight and besides, there was a brand new, diamond-bright replacement to step into the breach: The Northern Explorer. It came into service in June, 2012.

It was the first new train – well it had a new name anyway – to grace our tracks since the coining of services such as the Geyserland Express, Kaimai Express and Bay Express back in the 1990s. Others like the Waikato Connection and the Helensville Express had come and gone in the interim but their fleetingness hardly classified them as household names.

My wife Jenny and I were genuinely excited by the new arrival. Would the Northern Explorer presage another rail renaissance, as the significant developments of the Auckland suburban network had – and we conjectured about a completely new loop line disappearing beneath the streets of the CBD and turning Auckland into a real city. We planned to spend a day in the Queen City, checking out the rail upgrades after travelling on the Northern Explorer before returning home.

It was still the same old scruffy Hamilton railway station. The Britomart influence hadn’t extended south down the main trunk. It was funny to think the two cities under discussion, Auckland and Hamilton, both had had flirtations with underground railway stations. Britomart has a look of permanence about it, but they also said the same about the Hamilton Central underground station. Not in so many words perhaps, but dignitaries on opening day pontificated about ‘one small step for mankind’ and left it at that. Toasts were offered, ribbons cut and everyone nodded solemnly.

It seemed to be of some moment that the Hamilton Underground Station didn’t come to a blank-walled halt. Not like Britomart, as it now stands. The underground line carried on through Hamilton, up into the light and off across the Waikato River. Recent developments point the way to Britomart becoming part of the inner-city line. Its range beyond the blank-walled halt seems assured, while the fate of the Hamilton underground station remains the domain of soothsayers.

Back at the still scruffy Hamilton railway station – the one above ground – soothsayers were thin on the ground. There were a couple of railway employees manning the place; in what capacity, was never really established. We had no luggage to check in. Hand luggage was suitable for our needs. The station was just somewhere to sit and wait, but for how long, that was the thing.

‘Is the train on time?’ Jenny asked the elderly guy behind the counter, who seemed to be assembling magazines on the counter top.

‘Just left Otorohanga, ma’am,’ was the reply.

‘Te Awamutu wasn’t it?’ the other worker in hard hat and high-viz bright yellow chipped in.

‘Could have been.’

Silence then reigned, until disturbed as a south-bound freight gathered pace in the distance. Even after the goods train had veered east towards the centre of town and beyond to the Bay of Plenty and silence returned, the issue of the Northern Explorer being on time remained unresolved. It wasn’t even revisited as the elderly guy and High Viz thumbed through North and South and New Zealand Rail Fan magazines.

‘That’s a good one,’ High Viz said to the elderly guy.

‘What? North and South?’

‘Nah.’

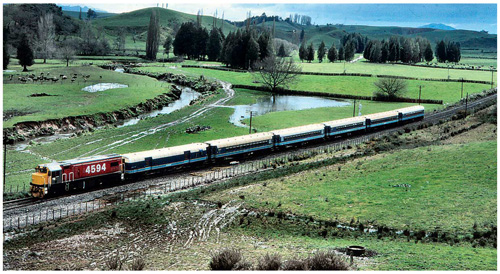

The Northern Explorer was on time. God knows what had just left Otorohanga. Or Te Awamutu. You could tell it was the Northern Explorer because it was like a new pin. At least the carriages were. The motive force was an old DC diesel, admittedly freshly painted, in grey, orange and mainly yellow. The carriages were a striking off-white and the most telling feature on first appearance was the size of the windows. There’d be no excuse for missing anything that passed by those beauties. As the brand new Northern Explorer tiptoed shyly around the curved platform at Hamilton, its make up became apparent. It had a rebuilt guard’s van as a luggage car which followed faithfully behind the engine and, in no particular order, three carriages capable of accommodating 189 passengers, a café car and an open-air viewing van which was also a rebuilt guard’s van.

As we waited on the platform for the train to clear of alighting passengers, a jovial guy in a brown denim jacket and cowboy hat jumped down. ‘Is this here, Hamilton, New Zealand?’ he asked of a slightly built young man, in a North American accent.

The latter, with puckish features and a twinkle in his eye took up the challenge. He seemed to have a sense of humour. ‘No siree. This here is Hamilton, Ontario, unless I’m very much mistaken.’

The jovial guy in the cowboy hat thumped the puckish traveller’s back sending him teetering towards the edge of the platform. ‘Hamilton, Ontario’s my home town, boy, but thanks for pulling the other one. Ain’t that what you say in New Zealand when you’re having someone on? You’re said to be pulling their leg?’

‘I guess so.’ The young man now just wanted to get on the train.

‘And when you’re really having them on you’re pulling the other one, huh?’

The young man said nothing.

‘So what are we talking about son? What are we pulling, huh? Legs or something else? Know what I mean?’

While this strange encounter unfolded, train and station staff hurried along, dealing with matters of luggage, tickets and general guidance. High Viz guy was just a yellow blur as he undertook a plethora of duties, none of which seemed entirely constructive.

As we climbed on board the concept of space was overwhelming. It may have been accentuated by the rucks and ruckus on the platform. Tall people used to stoop on cue climbing into most New Zealand carriage trains, but the Northern Explorer had a profound sense of roominess. The vestibule itself, unlike vestibules of old, presaged the general sense of space. It was hard to believe all of this came with the compliments of a 3 foot, 6 inch rail gauge. If you’d been out of the loop and didn’t know, you’d swear the standard New Zealand gauge had been widened.

Automatic sliding doors meant there were none of those awkward arm wrestles with hard-to-budge, below-the-waist knobbly handles.

‘Everything seems bigger,’ Jenny declared. She was referring to higher ceilings, wider walls, certainly bigger windows. There might have been some cunning optical illusions applied by railway construction teams, but good on them anyway.

We found our seats – 4D and 4C – and a man and a woman occupying them.

‘There are plenty of spare seats back there,’ the woman gesticulated with a sweep of her hand.

There indeed were, but that wasn’t the point. There was something about the set to the woman’s mouth that was unsettling. No one was denying 4D and 4C weren’t our seats, not even the woman, who continued talking to her male companion who looked about as set upon as we began to feel.

‘We can each have a window seat back there,’ Jenny said, unwilling to be drawn into a situation which would besmirch this singularly fine railway experience. Principles were abandoned. Points of order overlooked.

The train manager was laid back about the issue. ‘Sit where you like folks. Half the passengers in this carriage got off at Hamilton.’

Regimented the operation wasn’t. Even during the reign of the Overlander you were often obliged to sit in your allocated seats, even if it meant ten passengers clustered in a congealed blob in one corner, while the rest of the carriage looked like the single carriage tagged on the end of the Taumarunui to Stratford daily. Empty. Bereft of humankind.

Besides, who would want to sit too close to the woman with the certain set to her mouth? It wasn’t a quiet conversation she was having with her male companion. And it was full of invective.

‘It’s time Beth realised that bloody inheritance doesn’t grow on trees,’ the woman trumpeted. ‘Seven of those rental properties are earmarked for Guy, you know. Beth thinks she should be getting all seventeen.’

The male companion didn’t say a thing. He just sat there with a certain set to his teeth. This was New Zealand in 2012 – a different country. An ossified place where the rich have become super rich – and don’t care if they’re sitting in your seat. They probably own all the seats anyway.

Towards the front of the carriage a real Kiwi battler was totally preoccupied looking after his toddler daughter and a baby in a carrycot. The battler was a young father, and he had taken it upon himself to shepherd his flock on the Northern Explorer, all the way from Wellington to Auckland. The baby was restless, the toddler unreasonable. During the passage from Hamilton to Auckland, he was rushed off his feet.

A kindly middle-aged woman had taken it upon herself to watch over the little girl, while the father did his best to settle the baby in the carrycot, by carrying it up and down the aisle, hoping the increased motion would send the baby to sleep.

‘Anyone would think this was a crèche on wheels,’ the hard-mouthed woman declared, raising her voice. ‘Where’s the bloody mother anyway? I suppose he’s going to breastfeed it next.’

A well-known TV chef walked past, heading for the café car – where else? He looked so familiar neither of us could remember his name. Then came a columnist for one of the Sunday papers and when we couldn’t remember his name either we figured it was time for coffee and a bite to eat.

Moving around the train was a breeze, compared with the old days when crossing from carriage to carriage on crashing, swivelling steel plates, always seemed less safe than it could have been. It was one of the unspoken realities of train travel and one of the reasons that passengers tended to stay in their own carriages.

I remembered the time on the Overlander when I stumbled upon a frail old woman in a state of panic, stranded on the steel plate between carriages.

‘Don’t try to save me, sir. I’m done for,’ she yelled above the roar of steel on steel as the Overlander increased speed, making up time. The situation was a bit dire. I thanked the Lord she wasn’t on a mobility scooter or wheelchair or Zimmer frame, which on second thoughts might have been preferable, given that she seemed on the verge of collapse. God knows how long she’d been stranded, clinging grimly to the guide ropes as she sagged at the knees.

‘Don’t move, madam,’ I yelled back.

‘There’s no chance of that, sir,’ she yelled. I considered activating the device that would stop and train and incur a penalty of $100, payable by me. In a panic-stricken fog myself, I looked around for the small hatchet I imagined used to occupy a glass case on the vestibule wall. The idea, as I remembered it, was to use the hatchet to smash open life-saving equipment – perhaps fire hoses and the like – but I wasn’t thinking rationally. Was the hatchet to put a stranded passenger out of their misery as they waited, dangling, to meet a grisly fate beneath the train’s wheels? Suddenly the Overlander lost its pace and pulled into Hamilton Station.

Perfect. The solution to the problem. The colour returned to the woman’s face and she cleared the now still no-man’s land between carriage and buffet car with a sprightly gesture. ‘Bloody men,’ she directed up at me. ‘They build these things.’ I considered this to be valid venting given the previous situation.

In 2012 on the Northern Explorer I felt more justified than most in celebrating the fact that the navigation between carriages was a piece of cake. In fact a piece of cake to go with the coffee sounded inviting. I began talking to a guy waiting for coffee at the café bar. Or rather he began talking to me. ‘It’s a nicely appointed train but it’s the same old scenery out there,’ he said while waving his free hand towards the great outdoors. By now we had cleared Hamilton and its light industrial zone of Te Rapa, and were making good speed through the rural pockets this side of Ngaruawahia.

‘Yes. I guess we’ve seen it a thousand times before,’ I agreed. ‘Mind you, we get to see more of it through windows like that.’ I waved my free hand (the other cupped a container of potato gratin), towards the expansive café-car windows.

North of Ngaruawahia we kept an eye out for a tourist attraction set on a high hill, like something out of the Hobbit movies. If the Northern Explorer was a twenty-first century train, the hotel on the hill was also very contemporary. The old landmarks like the Waikato River, the Whangamarino Wetlands and all that came in between, were still beguiling. As the sun disappeared into the west, casting dazzling light into the carriage, the ancient presence of the Waikato River seemed as permanent as the sacred Taupiri Mountain and the old hills to the east.

Then we saw it, the hill-top hotel accessible by a deeply rutted road that shook dentures and tested car suspension as you drove into the hills above the Waikato River and the North Island main trunk. During the course of our stay there we had been able to look down on the crowded State Highway after dark, with car lights cutting through the river fog hundreds of metres below. From the south, a train lit up like the fifth of November could be seen overtaking the gridlocked cars. It was the Overlander heading north, running late at a time in midsummer when the expansion of rail lines further south had reduced it to a snail’s pace. Now, in the cool of early evening, it was pulling out all stops to get to Auckland at a respectable hour.

It was that experience which made us hanker after life on the main trunk line again. The Overlander, although we’d travelled on it many times, looked mighty inviting. In the nature of things, by the time we got around to booking seats, the Overlander had become the Northern Explorer.

Just this side of Huntly a fire alarm sounded. Or that’s what I thought it was. So did a couple of other passengers, who had sprung to their feet. The commotion continued until a woman, after ransacking her handbag, was able to control the cacophony. It was her cellphone – one with a novelty ring.

‘Hello Basil. You know I’m on the train.’ The woman had a voice that was louder than the train’s PA system.

‘I’m not prepared to go back to you unless you show some appropriate action to convince me your fling with Casablanca was just that. Something that was inappropriate and not likely to happen again, because if you try that on again mate, there will be appropriate consequences and actions I won’t be responsible for, if you know what I mean. And just because...’

Meanwhile, the PA system had come on to advise us the Waikato River was the longest in New Zealand. And other stuff we couldn’t hear because the cellphone person was raising her voice – appropriately or otherwise. Amongst the other stuff was an update regarding the Northern Explorer’s estimated arrival time at Britomart, bearing in mind that a bit of dawdling somewhere down the track meant we were twenty minutes late. We were informed of this when we arrived ten minutes late.

Meanwhile the cellphone person was sounding off on one side of the carriage and the PA announcements struggled through the intercom on the other.

‘And just because I’ve got three cellphones doesn’t mean you’ve got the right to listen to any of them, Basil...’

‘...service will be arriving into Britomart Station at...’

‘...not that it’s any business of yours but I’ve got three cellphones because...’

‘...apologises for the delay which has been caused...’

‘...and the third one is the one I use for important stuff because I know you listen to the other two. What choice did I have? You made...’

‘...and butter chicken is still available at the buffet car for the next...’

‘...if you do that stuff again Basil, I can’t be responsible for the appropriateness of my actions...’

‘...and potato gratin...’

The train staff could have been advising us to brace for a crash-landing for all we knew. Who needed endlessly awesome and unfamiliar scenic delights when fellow passengers were providing an on-board slanging match?

The scenery along the Waikato River and through the Whangamarino swamp is always enticing, no matter how many times you see it. The mood and flow of our longest river, its colour and current always full of contrast. And travelling on the Northern Explorer, the new train built for scenery watching, affords you chances to see aspects of the countryside you’ve never seen before. Larger windows can open up new vistas.

Back at our seats the potato gratin was warm and tasty. Jenny’s butter chicken and rice stood up well too, except when the plastic cutlery proved too puny. You never knew if you had total control over a forkful, especially when the train lurched. It has to be said that the Northern Explorer was a very stable train. Someone had put a good deal of effort into balancing the bogies.

It would have been much easier carrying a hot pie and cuppa back to your seat if the Northern Explorer had taken to its wheels in the 1960s. Mind you, back in the 1960s everyone would be doing the same thing at virtually the same time. It was an egalitarian exercise getting to and from the refreshment rooms back then. In 2012, on the Northern Explorer, you had a wider ranging clientele who free-ranged and grazed in their eating habits, and they weren’t all Kiwis.

Even though times have changed, I’ve always treasured the train ride north to Auckland from either Te Kuiti or Hamilton, even when a good portion of it took place in darkness. For a start it was only two or three hours’ worth of travel, either with the dawn breaking on an exciting day for us young bucks or the sun setting in later years along the northern reaches of the Waikato River. Three hours seemed like a goodly amount of time to spend on a speeding train. Beyond that boredom can set in and fellow passengers can become a bit too familiar.

The glistening Waikato heaved out of sight to the west beyond Mercer, and the sun sank in the August sky. Beyond Pokeno the main trunk parted company with the motorway and shifted north beyond Tuakau towards Pukekohe, after travelling due west for some time.

The train was making up time as we encountered the edges of the sprawling Auckland conurbation, where darkness continued to fall and lights were popping on in streets and houses. Just beyond Pukekohe we whistled through Paerata, junction point of the Mission Bush branch feeding the huge Pacific steelworks. It used to function as the suburban line to Waiuku until 1968, when the branch ceased operating. A fellow rail fan friend of mine once lived in a railway house with his family and he used to delight in recounting the hi-jinks young boys got up to on branch line trains. He also remembered hearing about some of the close calls that were associated with the morning train from Waiuku which ran down the branch and connected up with the Auckland suburban network at Pukekohe.

It always struck me as being a bit odd, having a branch line to Waiuku. The latter, even back then, seemed to be on the way to nowhere. If it went much further it would end up in the Tasman Sea. If the authorities had it in mind to extend the line south there was the small matter of the yawning Waikato River delta to bridge.

The business of politicians and railways entered the argument – and how branch lines could end up going in the darndest direction if a personage of prominence and influence had a property perched on some isolated promontory. Such wayward lines had little to do with providing social services for the majority, but, in the case of the Waiuku branch, served the selfish motives of the Reform Prime Minister, William Ferguson Massey, through whose Franklin electorate the Waiuku branch was built.

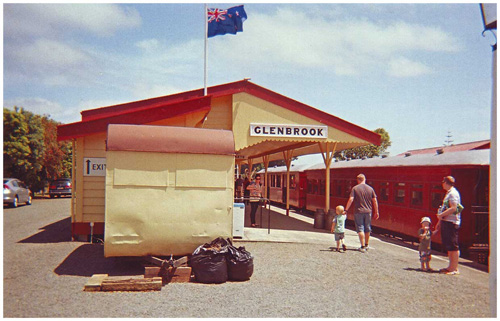

In recent times we could say we’d been on a section of the old Waiuku branch, reinvented as the Glenbrook Vintage Railway. The latter was a brilliantly restored and replicated heritage operation running from Glenbrook Station, near the steelworks to the very edge of Waiuku township. Any selfish motives displayed by Prime Minister Massey all those years ago were forgiven when we realised his playing political games led to a rail environment in which the Glenbrook Vintage Railway could play with their life-size toys, for the considerable enjoyment of train buffs like us. And for those younger generations who wanted to know what trains and railways were all about in a bygone era.

Back in 2012 I mentioned to Jenny that the Northern Explorer would provide a spectacular sight as it came into Britomart Station, heading along the waterfront, after deviating east beyond Westfield. She’d be able to see all the ships lit up.

There was quite a commotion on board now, for although the Northern Explorer carriages are noted for their smoothness and quietness, passengers and staff were making ready for quick getaways. Cupboards and cabinets were being slammed shut, hand luggage was dropping noisily from overhead racks, bottles and crockery were clinking. It was enough to wake a hundred babies, yet the baby from Wellington slept through it all. The father, after his child-minding marathon, did the same. The little girl was starstruck by the inner-city lights. Jenny had nodded off too.

I swear I always thought that trains arriving at Auckland at night approached Britomart along the waterfront route. Certainly the Overlander did the last time we travelled on it. But here we were heading up past Ellerslie, Greenlane and Newmarket before sneaking in the back way to Britomart.

‘Did I miss much?’ Jenny asked.

I could have said something about missing at least ten American cruise liners, all lit up like Christmas trees, and hundreds of ferries and other marine craft with their lights dancing and reflecting off the choppy Waitemata like glowworms. But even I could see, as we crept around the tight curve from the Newmarket line to the Britomart tunnel, that a heavy fog obliterated anything worth seeing along the waterfront.

It was my saving grace. There was no disappointment at the end of a remarkable train journey, although we declared the viewing van to be a bit sparse. Just a bit.

Postscript

We had a spare day in Auckland before returning home to Hamilton, so, in the interests of appreciating new developments in the Queen City (as well as it being the terminus and departure point for the new Northern Explorer) we took a look at the considerable improvements to the western line. We also took a run on the revamped Onehunga branch line, a route with a considerable history. Prior to the opening of the main trunk line, boat trains used to carry passengers scheduled to catch a steamer at Onehunga wharf, along the short branch. The steamers sailed to New Plymouth where the completed through line linked with Wellington.

Having reached Onehunga by train in 2012 at least we could say we had touched base with another virgin stretch of New Zealand line, albeit on the short side. The rail official at Onehunga station, an Indian, was on the short side too, but he was most determined to instruct us in the ways of the new automatic ticket dispenser, due to come on line in the next month or so.

I approached the machine with money at the ready. Obeying instructions I inserted what I considered to be the appropriate amount and pushed a button or two. Nothing happened, yet when it did, it seemed sluggish. I pushed a few more buttons.

‘No, no, no,’ yelled the rail official. ‘Please be waiting for your money to descend. Then push, push, push your destination key.’

This I did.

‘No, no, no. Don’t be pushing it too soon. Wait, wait, wait for the yellow light. Go back to start and retrieve your money. Push retrieve but – no, no, no – not until the green light is flashing. Your money will not come out. Oh, oh, oh. No, no, no.’

‘We simply want to travel from Onehunga to Waitakere. Perhaps if we just paid for it on the train. Presumably the guard has a ticket book.’

‘Oh yes, yes, yes. But no, no, no, you must get acquainted with the new automatic ticket system. It will be introduced at the end of the year and you will be stranded if you don’t come to grips with it.’

The official was clenching his fists as he dispensed this final advice and we were pleased to be on our way. We caught up with the Waitakere train at Newmarket.

On the service to Waitakere some dislocated voice reminded us to: ‘Please beware of the gap between the carriage and the platform.’

Auckland, 2012, and it’s hard not to notice the gaps. Mainly between the haves and the have-nots and across the generations. Auckland is suddenly a big city and that means a wide-ranging ethnic mix on your everyday feeder trains. Even a few tourists. At Kingsland Station a group of Americans off a visiting cruise liner climb aboard, all speaking at once. They are middle-aged and kind of prosperous looking. A bit over-fed too. They’d been visiting Eden Park, scene of New Zealand’s Rugby World Cup win the previous year.

‘The All Blacks beat All France, huh,’ a friendly Texan announced. ‘Eight goals to seven. One is always enough, I say. No point in overdoing it, eh? One hundred and eight to seven means the same thing, eh fella. It’s only a game. Gridiron came first anyway.’

Whether I knew it or not the above pronouncement had been directed at me, although the jovial Texan appeared to be directing his diatribe to the whole carriage. At Mount Eden most of the passengers got off. A young mother with a pramful of twins, a younger couple of indeterminable race, furiously texting, probably to themselves. How could they be aware of the gap between the carriage and the platform? Wagging schoolkids wearing an unappealing uniform of green, blue and purple. An Asian guy with orange mohawk squeezing through the doors at the last minute because his cellphone, making the sound of a jazz musician playing out-of-tune vibes, summoned him at an awkward time.

More Americans off the Pacific Princess got on at Mount Eden. None of them were underweight. One of them introduced himself to his fellow Americans. He used to work on oil rigs and originally came from Detroit, when Detroit was OK. Detroit’s derelict now, so I guess that was the point he was trying to make. He was OK because Detroit used to be OK – in the days of Motown music and prosperous car assembly lines. You can learn a lot about America while travelling in a New Zealand train.

There are certain things you don’t want to learn about some New Zealanders. Jenny and I both sensed danger when a young man and woman climbed on board at Henderson. The young man sported a smirk that screamed self-absorption. His partner, bearing tattoos that were less ethnic than emblematic, shoulder-charged her way past an Asian girl who was i-Podding with one ear and listening to a cellphone with the other.

Some people sit demurely in train seats. Some slouch. Others sprawl with legs akimbo. But our Tarzan and Jane sat with a twitching swagger. Poised to strike if anyone should as much as turn a head towards the vicious conversation they unleashed as the train headed for Ranui.

It’s amazing the scenic highlights fellow passengers are able to identify at such times, pretending to disregard the expletive-charged spat between the man and woman. Even the guard, a pleasant English woman, suddenly took an interest in us and asked if we were going all the way to Waitakere.

‘You deleted my effing message,’ interrupted our reply, as the man reared up after prodding a cellphone, and virtually spat at his partner.

‘You deleted your own effing message,’ the woman replied, as both got up and left the train at Ranui, trailing curses, violent hand gestures and plastic soft drink bottles.

‘It’s best to pretend they don’t exist,’ the English guard advised. ‘If you so much as stare at them they’ll challenge you. Sometimes I think they just fabricate a domestic argument and hope an innocent bystander takes the bait. It adds a bit of excitement to their pathetic day.’

A week later a news item announced that a 29-year-old male had been murdered in Ranui with a blunt instrument. We couldn’t help but make the macabre association. Was that the result of another fabrication?

‘They’re all the same,’ the guard had said so it was probably someone else. And yes we did make it all the way to Waitakere – just as the threatening skies exploded. Heavy, near horizontal rain dumped. The new automatic ticket dispenser, not entirely protected from the elements, saw us drenched and dumbfounded as we tried to put into practice the instructions given to us by the attendant at Onehunga Station. Had the rain been factored in to the setting up of the new ticket system? It was certainly getting in, but that was different.

Travelling on the Northern Explorer – a new train on the old line – and checking out the upgraded Auckland suburban services – newish trains on newish lines – gave us a glimpse into the future. The Northern Explorer was advertised as a tourist train. We were tourists I guess. We certainly didn’t feel like commuters. We met Americans and travellers from Invercargill. Journalists, chefs. We also shared a carriage with privileged and underprivileged Wellingtonians. In between times we made like commuters in New Zealand’s largest city. And still we met Americans. And a wretched breed of hometown underclass, turning feral.

We didn’t quite make the new service to Manukau, but it’ll keep. It was only 1.3km of new line, but it was brand new – that’s the thing. Brand new lines will soon become common in Auckland as the city wakes up at last to the importance of rail.

But we were chuffed to make it on to the historic Central City to Onehunga branch, one that had finally been resurrected as a commuter line in 2010. We sat next to a pimply gentleman with wires protruding out of both ears, connecting to high-tech devices, the next best thing to a twenty-first century robot – and I couldn’t resist calling up the past.

‘Trains on this line used to carry passengers all the way to Wellington, via Onehunga wharf, steam ship and the train service from New Plymouth to the capital.’ When the young man on the Onehunga train realised I was talking to him, he removed an electrode from an ear.

‘What?’ he said.

I repeated my comments whereupon the young man grinned and re-wired himself.