Travelling to Gisborne by railcar in 1967 was like going to another country. It started out in confusion – Wellington to be precise. After a sleepless overnight jaunt down the main trunk on the faithful express, I joined my fellow zombies, who hadn’t slept too well either, as we merged with men in grey flannel suits and women in largely sensible shoes – the incoming commuters – as we struggled for movement and oxygen in the echoing cathedral of Wellington Station.

It was already like going to another country. I had communication difficulties with the ticket seller, not because he was speaking a different language or dialect, but because of the gales of sound generated by too many people talking at once in too small a space. It was hard to hear yourself think and that last pie at Palmerston North – or was it Paekakariki? – was repeating on me. My stomach was singing a song of its own, adding to the cacophony.

Another country too, when a tiny man wreathed in a blanket made eye contact with me.

‘Got any money, sir?’ he asked through, or around his remaining front tooth, in a distinguished British accent.

‘Yes I have,’ I replied foolishly, but innocently.

‘My dear grandmother, at this very instant, has just passed away in Plimmerton. Can you lend me a guinea to travel to her funeral?’

‘I’m running late, sir,’ I said and hurried away. I was too.

‘Anyone would think you had a confounded train to catch,’ he yelled after me.

I did.

I still don’t know what really happened in 1967, on that winter’s morning. Through the dog-tiredness and diversions I had somehow managed to buy a ticket to Gisborne. Wellington to Gisborne. I went looking for my connection. The train I ended up on was a railcar travelling via the Wairarapa line, hopefully to Gisborne. See Wairarapa by train, the poster on the station wall back home in Te Kuiti had implored. I thought I was killing two birds with one stone.

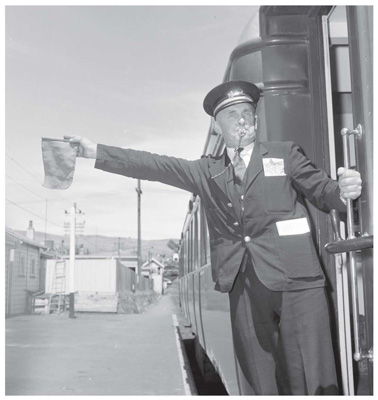

Apparently there was another railcar, at another platform, which was heading north another way – up the main trunk, then through the Manawatu Gorge to Napier and on to Gisborne. I think my ticket was made out for the latter service. The guard got a bit grumpy when he discovered I was technically on the wrong train, although the destination, Gisborne, was valid.

‘You’ve got the right ticket, but the wrong railcar,’ he grumped.

‘Or wrong ticket, right railcar,’ I replied helpfully.

The guard made a comment I didn’t understand, but the important thing was that I wasn’t thrown off at some hell-forsaken Hutt Valley suburban station, as we headed for the Rimutakas and Wairarapa.

It was pre-dawn as the railcar disappeared into the Rimutaka Tunnel. The suburban lights suddenly disappeared as the total blackness of the tunnel drew your focus to fellow passengers, most of whom had that early-morning look in their eye.

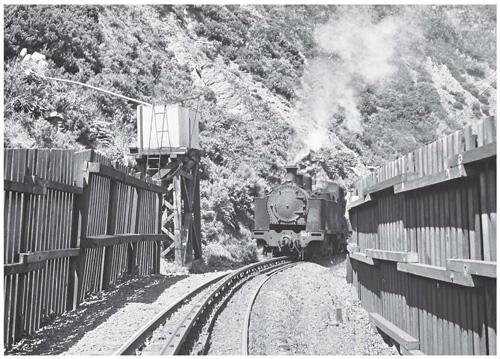

The tunnel was opened in 1955. I remembered seeing black-and-white glossies in the Weekly News, depicting the opening ceremonies, in which an English electric diesel – a DG – pulled the official train from one side of the ranges to the other. Pictures of what had gone before – the days of the Rimutaka Incline – also graced the pages of the Weekly News. The deeper the railcar delved into the tunnel, the starker my memories of the old incline became. My grandmother’s voice describing the journey came back to me in fragments. She used to travel on the incline when visiting a friend in Featherston.

As the railcar swished and swayed through the eight-kilometre-long tunnel, I swore I could hear the disjointed huffs and puffs of the old Fell engines as they worked manfully to haul the incline trains up the steep gradients. Mind you, being half asleep probably bolstered the sounds of the railcar, with some of the sound effects coming from my own dream-like state.

It was amazing to contemplate all that rail history unfolding in the hills now safely behind us. I’d had enough trouble contemplating the current phenomenon of the Rimutaka Tunnel, which had been opened in 1955, and by 1967 already had a history of its own. And here we were thinking that the two Tawa deviation tunnels on the main trunk were as long as tunnels got on the New Zealand system.

The hills behind us used to pulsate with the sound and fury of the Fell engines. The old man sitting next to me painted a picture of those halcyon days. I guess he’d detected my enthusiasm for the landscape once the railcar emerged from the long tunnel, from pre-dawn murk as we entered the eastern portal, to the shadows washed by the rising sun as it highlighted Lake Wairarapa.

The latter was a large lake, one I didn’t know existed. It stirred a sense of discovery in me, to think such a substantial body of water nestled on the plains beyond the Rimutakas, and it had never occurred to me to go looking for it.

‘It’s been there a while,’ the old man said as I registered my surprise. His comment exposed my lack of knowledge of our country – off the beaten track. As the sun rose, the wide Wairarapa Plains revealed themselves to the traveller.

The old villas we passed on our way through Featherston were distinctive. This was another New Zealand entirely. It had an established look about it, unlike our neck of the woods and many of the main trunk towns. Time seemed to have passed towns like Featherston by – after all, the railway opened on this side of the Rimutakas back in 1878, but in subsequent years the more direct route north out of Wellington had gained in prominence.

The first train over the Rimutaka Incline – a sort of pilot train – was made up of a brake van behind the Fell engines. Temporary seats had been set up in the van. Four days later the first general train arrived in Featherston, creating quite a furore. One hotel proprietor was seen pushing a keg of beer in a wheelbarrow towards the station, where many had gathered. Some individual citizens were hot on his tail, their pockets bulging with celebratory bottles. It was quite a day for Featherston as townsfolk, passengers, and even train staff marked the occasion with much ribaldry and mirth. By contrast, the official opening ceremony at the station a couple of months later was a complete fizzer. There was no train at all and heavy rain dampened spirits even further.

My grandmother spoke about the Rimutaka Incline in wondrous tones, but we were too young to take on board her accounts of passenger trains with five small engines placed at intervals between the carriages, trains with a third rail for adhesion, such was the steepness of the gradients.

We pricked up our ears the time she spoke of the day a ferocious gale blew a train off the tracks and into a gulley. Three young girls were killed at that spot, known as Siberia, and the rail authorities erected a large protective fence to prevent such an accident ever happening again.

She also told of the time an express train became stalled in a tunnel and the choking smoke became a nuisance for the passengers. Some panicked and climbed out of the carriages to escape the smoke. Unfortunately, the smoke in the tunnel was thicker than that in the carriages and the panic-stricken took little coaxing to get back on board. Eventually the stalling engines got a grip and most people emerged with a little smoke damage, although several had suffered scrapes when jumping into the tunnel wall.

Up in the Rimutakas, serving the incline, were railway stations which were uniquely remote. Summit Station, perched predictably on top of the ranges, could be a god-forsaken place. It was totally exposed to the roar of prevailing winds and had an annual rainfall of 266cm. There was little escape for railway staff. At no stage was there any road access to Summit.

Cross Creek was regarded as a ‘salt-mine’ railway settlement, where wrongdoers were sent to contemplate their wild ways. The weather always seemed to be unwelcoming – not at all like today, when the Gisborne-bound railcar reflected the sunshine all day long, which soon burnt off lazy pockets of fog and mist.

We saw Wairarapa by train. It was a great way to touch base with the fertile plains and snow-capped mountains to the east and west. Greytown and Carterton flitted past with the sun filling most corners of the Fiat railcar. At Masterton it was time for refreshments and, although the hot pie and cuppa were welcome, the highlight was standing in the bright sunshine and contemplating a place I’d never seen before – certainly not by rail.

The rest of the morning and early afternoon passed in a flash. Wairarapa gave way to Hawke’s Bay, where Eketahuna, Pahiatua and Woodville led to Dannevirke, Waipukurau and Waipawa. Then Hastings and Napier were upon us.

Napier seemed like the end of the line. By now we had been travelling for several hours and it was mid-afternoon. So many passengers alighted here you had to check timetables and departure times to make sure the final link with Gisborne to the north had been factored in.

Before long the railcar was swaying north. The suburbs of Napier receded. Those who had remained on board, or had caught the service at Napier, soaked up the seascapes as the line rimmed the ocean through Westshore and Bay View. I remembered my geography and history. This was the region so badly affected by the 1931 earthquake.

The line headed directly inland on encountering the Esk River outflow and now we were tracing the course of the river as it flowed through the hamlet of Eskdale, with its fruit growing and farming downs. A couple of kilometres beyond Eskdale the line did what railway lines do so well – it headed into territory unaccompanied by any road. The Esk River was our only companion as we headed due north.

I could now confidently say I was traversing genuinely personal virgin territory. I had been vaguely aware of being in the back of our car as the highway accompanied the line down to Napier, one Christmas long ago. Now we were also climbing, as we rejoined the Gisborne highway at Tutira, near the northern limit of Lake Tutira, a bird sanctuary.

The hills were parched. We were climbing into an environment I hadn’t encountered before. Where the hills weren’t parched, they had great white erosion scars down their faces, evidence of heavy rain. Obviously this was a region of extremes.

At Napier Ray had joined me in the aisle seat. He was middle-aged and had the close-cropped, windburnt look of a farmer. He didn’t say much, but what he did say was significant. There was very little small talk with Ray.

‘Do you realise that in 1957 the biggest landslide in the history of New Zealand railways came down at Wakakopu Bluffs, just up the track?’ That was the first thing Ray said to me, about half an hour after we’d headed out for Gisborne. He had a certain tone to his voice, which almost made me feel responsible for the landslide.

‘No. I had no idea,’ I replied.

‘Over a million tonnes of clay and papa rock slid into the sea, making a brand new peninsula.’

‘Wow. That’s a lot of clay.’

‘And papa rock.’

Ray was nothing if not pedantic, and here was I about to make a disrespectful comment about Papa Rock being an American disc jockey. I refrained.

Another twenty minutes passed. Ray remained upright in his seat. His head seemed to lack motility. It barely turned left or right.

‘People don’t realise the Gisborne to Wellington Express that was in existence before this railcar, was the longest provincial express in the country. Five hundred and twenty-five kilometres.’

‘That’s a long train,’ I replied.

For the first time, Ray turned his head to the left and gave me a withering stare. ‘It ran for five hundred and twenty-five kilometres. No train could possibly be five hundred and twenty-five kilometres in length.’ Was Ray a schoolteacher – a close-cropped, windburnt one – and was I the naughty schoolboy in a weird out-of-school encounter?

Luckily Ray wasn’t long for the railcar. He got off at some obscure siding, but not before he had handed down some further pronouncements.

‘Do you realise Beach Loop is only accessible by train?’ I didn’t. Nor did I know that Beach Loop was way up the track. I thought it was some sort of local summertime variation on the hula hoop, but I kept that thought to myself.

‘Not many people know this, but the land at Beach Loop is moving all the time.’ That was Ray’s parting shot as he gathered up his briefcase, straightened his tie, and headed for the vestibule. Or so I thought. ‘Just remember,’ Ray yelled down the aisle, ‘we’re lucky to be here, what with earthquakes, depressions, floods, storms, slips and mechanical problems. Enjoy your journey.’

‘He’s right, we are lucky to be here.’ This statement came from an elderly woman who had climbed on board just as Ray got off. This was Pam and her cheery interpretation of the ‘lucky to be here’ cliché was a million miles – and certainly 525 kilometres – away from Ray’s dire, close-cropped, windburnt prophecies.

Pam replaced Ray in the seat next to me. Which was good and bad. Good in the sense that she was pleasant and predictable, bad in the sense that there weren’t enough pregnant pauses in her speech patterns to enable untrammelled concentration when the railcar was climbing through vertiginous back country fit to take your breath away, or skirting dazzling bays you’d never seen before. At a juncture when a first-time traveller was keen to take in the matchless scenery, the constant prattle of your travelling companion was as irritating as the staccato clacking of her knitting needles. Or the occasional vibration and rattle of the railcar.

‘Oh that damn rattle,’ Pam said. ‘You know, sometimes it rattles so much they call it the Red Rattler.’

The railcar entered a tunnel and the notion of the red rattler played on my mind. There are red rattlers all over the railway world. There was a classic old intermediate suburban service that met the Sydney to Newcastle trains before travelling downhill from Fassifern to Toronto on Lake Macquarie in New South Wales. Many years later I supervised the travel of my young daughter and two nieces on that particular old red rattler and we had an uproarious time. The girls jumped from seat to seat and only settled on their preferred seating arrangements when the train pulled into Toronto Station. Then, after ice creams and a bit of window shopping, we made a mad dash back to the station where I saw the return train was waiting. It didn’t occur to me that the train which had deposited us there was the same one scheduled to take us back. It hadn’t moved since we got off.

That didn’t stop me cracking the whip, particularly when I heard what could have been the departure bell. One of my nieces later told me it had been a local bird, whose cry sounds a bit like a bell. My daughter and both nieces took tumbles as we scrambled down the gravel road to the station. Knees were skinned, and tears welled as we sat in the carriage for another 20 minutes. Serious looking women climbed aboard, glancing suspiciously at the three young girls gingerly dabbing their grazes with handkerchiefs. As their obvious guardian, I received the most withering stares.

The Gisborne Railcar was edging past yawning views of the Pacific as I returned to 1967 – and Pam’s prattling. We had never met before but that didn’t stop her assuming I knew everyone living in the Raupunga and Kotemaori area. Mrs Braithwaite’s cousin’s sister’s aunt had almost fallen down an offal hole, but worse was to come. Mrs Braithwaite’s cousin herself almost fell down the same offal hole. Near Waihua, Pam suddenly stopped her knitting, leaned across my bows and waved vigorously at a carload of elderly folk keeping abreast of the railcar, near where the line and the highway cross the Waihua River, heading for the sea.

Pam apologised for reaching across and wouldn’t hear of it when I suggested that perhaps she might like to take the window seat, if she had any more cars she had to wave out to between here and Gisborne. It was a magnanimous gesture on my part, and I was secretly praying she wouldn’t avail herself of the offer. Scenically the Gisborne rail route was a glorious surprise. I was still in another country. No one had told me it was this good. No one had told me anything.

Luckily Pam declined. Initially I preferred to think she understood my infatuation with the physical grandeur, but eventually as her clacking needles returned to their staccato pitch, she revealed something of the insularity of Poverty Bay, or maybe it was just those travelling on the railcar.

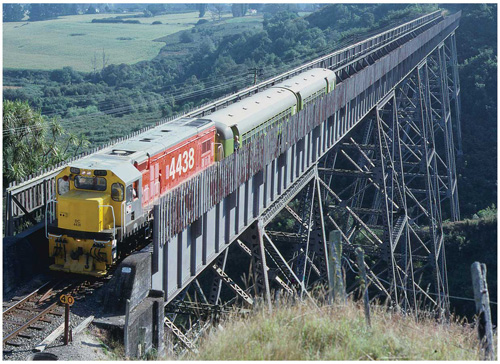

‘No. You stay there, young man. I’ve seen it all a hundred times before. Besides, I’ve got no head for heights.’ She was obviously referring to the yawning cliffs along which the line sometimes ran. And certainly the viaducts. Mohaka, a few kilometres back, was a case in point.

The Mohaka Viaduct. One minute we were rattling along, Pam keeping time with her knitting needles, clacking in unison with the clickity-clack of the rail joins. The clacking and the clickity-clacking were enough to take your mind off the enormity of the scenery. Next minute there was an almighty roar.

We weren’t up in the clouds but we may as well have been. Countless metres below flowed the Mohaka River. It was impossible for the slat fence to hide the vertiginous gap in the land. If this was just a minor branch line petering out somewhere to the north, how come such a magnificent coathanger had been built on it?

The Gisborne line was full of such surprises, and made you appreciate just how stupendous were the feats of engineers and navvies. Of course you had to question the need for slat fences along both sides of the viaduct – through similar terrain on the main trunk, no such add-ons were deemed necessary. And that made the sudden emergence onto the Makatote, Mangaweka or even Waitete Viaducts all the more head-spinning. They made the girls scream. I know my sisters nearly fainted, and my mother had ‘no head for heights’ either.

As the Gisborne railcar seemingly took to the skies, I became quite animated. Why hadn’t someone at school mentioned this feat of man-made engineering over a freak of Mother Nature? It wasn’t the main trunk. That’s why.

‘This here’s the highest viaduct in the Southern Hemisphere, young man,’ Pam announced, halfway across. The chasm was like a moon crater. In the following weeks I was to learn the Mohaka Viaduct was 95m high and contained close to 1815 tonnes of steel. It was indeed the highest viaduct in the Southern Hemisphere. And our funky, spluttering Fiat railcar, a humble rail carriage, had taken it all in its stride. Oh, and it contained 450,000 rivets – the Mohaka Viaduct, not the Fiat railcar.

At this stage, what with the hulking viaducts, land carved up by nature, and place names I’d never heard of, things were becoming a little too unfamiliar. We could have been in Nepal or some South American republic near the foothills of the Andes. When the guard mentioned we would be pulling into Wairoa soon, I was reassured. I’d heard of Wairoa. And I could celebrate our arrival with another pie.

There was considerable celebrating when the line from Napier to Wairoa was completed and officially opened. ‘A day of rejoicing’ the press of the day claimed. The coming of the railway meant so much to the people living in the hitherto isolated town and region that, as a consequence, the locals and invited guests celebrated long and hard. Even now I could sense the magnitude of the line, and appreciate how it would have been seen as a saviour. It would have meant reducing reliance on the saddle-track roads to both north and south, which were often impassable and flooded. And it would have been a way to outwit Mother Nature, who had dredged up a treacherous bar at the mouth of the Wairoa River, able to thwart the attempts of even the smallest coastal vessels to relieve Wairoa’s profound isolation.

It was said that such isolation was exacerbated by the resistance of local Maori to the invasion of Europeans. This impacted on procuring land suitable for the passage of a railway line. As a consequence, the east coast line was one of the last to be completed and the Napier–Wairoa segment had more setbacks than many other major transport construction projects.

In 1967 Wairoa Station was quietly going about its business when the Gisborne Railcar pulled in. Refreshments were available. Another pie for sure. Yet back in 1939, on the occasion of the opening of the line, hundreds of expectant locals thronged the beflagged station and platform, waiting for the first official train. In fact three trains arrived in a short space of time and 1500 visitors from Hastings, Napier and most points in between climbed down to join in with the locals on the occasion of the opening day.

It felt significant to be travelling by railcar in 1967, for it was another railcar – a Standard model driven by the Hon. D.G. Sullivan, Minister of Railways, which transported political heavyweights to that long-ago opening ceremony. After the official party had been escorted to the dais, the mayor said a few words. Then the Chairman of Wairoa County Council, followed by the member for Hawke’s Bay and the equivalent for Gisborne did the same.

Railcars also provided the first regular passenger services along the new link and beyond. A twice-daily service in each direction, utilising the new Standard railcars, did away with the need to trek for nearly four hours on the rough hill-country roads. Two hours ten minutes was all it took to get to Napier, and you could travel in comfort on the smooth steel road. The first railcars even had names: Tainui and Takitimu, named after canoes of the great migration fleet.

The 1967 railcar didn’t have a name. Over the intervening years, the passage of the Gisborne railcar had become as everyday as the turning of the tide. As a result, the Wairoa Station experience was less than memorable. I barked my shins on a low-slung baggage trolley and my pie was lukewarm. Mind you, it was my fourth for the day after Masterton, Woodville and Napier.

And then there was a difference of opinion as passengers climbed back on board.

Someone said the railways should be likened to education, health and other social services which were not expected to function as business enterprises. In 1967, the Rogernomics revolution was still twenty years in the future. In 1937, as dignitaries gathered for the opening of the Mohaka Viaduct, the Minister of Railways felt constrained to remind onlookers of the need to see railways as being vital for the development of the country and not to be viewed from a narrow accountancy perspective.

As we pulled out of Wairoa and headed eastward towards the sea, it seemed daft that railways could be viewed as strictly a business. More than most lines in isolated areas, the Gisborne link served less tangible social and logistical purposes. Gisborne and large tracts of Poverty Bay may never have progressed without the ambitious railway that soon, after all that inland climbing and curving, was about to show off its other side.

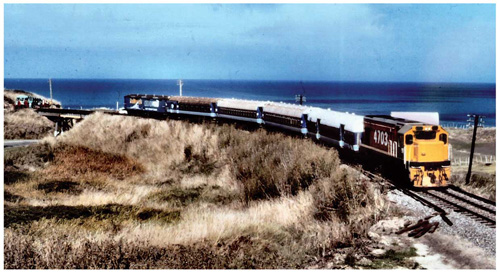

Just beyond Tuhara, Whakaki Lagoon appeared next to the tracks, and beyond that the wide expanse of Hawke Bay. Apart from a brief flirtation with the coastline just beyond Napier, the ocean had disappeared. Such was the awe-inspiring, almost overwhelming presence of the ridges and valleys between Eskdale and Wairoa, you had the feeling this section of the line was all about rural backblocks, massive viaducts and rugged, broken country far from the sea. Admittedly, there had been a glimpse of the Pacific back at Waihua but beyond Wairoa the line took on a different aspect.

Mahia Peninsula became more prominent. Being a complete novice I thought the line might travel down the peninsula. And then what? Come back again? Perhaps the line travelled across the peninsula. I asked the man who had been sitting behind me since Wairoa. He didn’t know.

Beyond Nuhaka the line carried on due east. The main road, which had been a constant companion, left us to it and veered away to the north. Before you knew it, the line was snaking around the edges of popular beaches such as Waikokopu and Opoutama, to take a northeast course towards Gisborne.

What a buzz it must have been, camping with the family at a beach settlement like Opoutama in the 1950s, where the Gisborne line came edging around the corner between the rocks and cliffs. If you were lucky, the Gisborne Express roared past on its way north to the easternmost reach of the New Zealand rail system.

I remember seeing a photo of the Gisborne Express – a KA-hauled summer version with six steel-panelled carriages and a guard’s van easing past a bunch of kids swimming at a beach – it may have been Opoutama. With its KA hauling steel carriages, it could have been the overnight Limited on the main trunk, but here it was, virtually running along the beach. In the photo none of the kids are acknowledging the train, although a few parents sitting on beach towels are inclining their heads towards the mighty KA and the Gisborne Express, which seemed totally out of place in such a backwater.

You can imagine the passing train full of happy faces – the bucket and spade brigade – on its way to Gisborne, or Bartletts or Muriwai, beach settlements south of the city – or even to Opoutama itself. It would certainly be a unique experience. The Gisborne Express might have looked like the Overnight Limited but I know, from personal experience, that there were no bucket and spade brigades on that particular landlocked, moonlit vessel.

In 1955 the express stopped running, to be replaced by the Fiat railcars. The Gisborne Express covered the longest course of any New Zealand provincial express – 525 kilometres, as Ray had it back down the line near Napier. Of course the 1967 railcar had to cover the same or a similar distance, which could account for the fact we began losing the light of day some distance from Gisborne. A group of railway track maintenance men climbed on board at some unscheduled stop. The fact that they appeared unheralded out of the murk caused murmurings. Were they taking over the railcar? Before their boisterous intrusion I was sound asleep.

We seemed to be descending on the outskirts of Gisborne. It was now quite dark. The railcar lights were on. The railways maintenance workers were chattering away as the railcar swirled and swayed. Suburban lights burned through the early evening murk.

The maintenance men were friendly, although they were a bit miffed that the railcar, their transport back to the city, was running half an hour late. At this time of year half an hour made all the difference between getting home in light or dark.

‘You off to Gisborne then?’ one of the workers asked halfheartedly. It was a rhetorical question. There were no more stops and the railcar didn’t run beyond Gisborne.

‘Yeah. Never been there before,’ I replied.

‘Why didn’t you come by plane?’

‘I wanted to see the land.’

‘It’s pretty much all the same, whether you see it from thousands of feet or close up. Flying’s quicker.’

‘I like trains.’

‘Fair enough, eh. You just got to make sure you fellas don’t bang into a plane when the railcar crosses the airport runway. We thought you fellas must have crashed into a Fokker Friendship. That’s why you were late.’

My mystified look motivated the maintenance worker to fill me in on one of the great oddities of the Gisborne line. Apparently the railway runs across the Gisborne Airport runway, or the runway runs across the railway, depending on your point of view. The runway needed to be extended when the new Fokker Friendship aircraft was introduced. Suggestions the railway line should be moved closer to the sea, and out of harm’s way, were countered by cost considerations and the increasing reality of relatively light traffic for both trains and planes. So a carefully monitored security system enabled the railway to remain where it was and the runway to extend over the top.

I was fairly sure we hadn’t crashed into any aircraft – in fact I didn’t even see the airport. Perhaps I was looking out the wrong window. Perhaps I had nodded off.

A girl with a transistor radio had gone to sleep. ‘Glad all over’ blared out between the swishes and frequent honks on the railcar horn. Level crossings increased, with their jangling bells and flashing lights. The inner city was upon us. One or two passengers reached for travel bags from the skinny overhead baggage rack.

‘Glad all over’ was followed by a song that was immediately recognisable, yet strangely unfamiliar. A couple of months earlier the Beatles had sung ‘All you need is love’, on a worldwide satellite TV link-up. Then the song had retreated into the cosmos, as it was fine-tuned and later released as their new single.

Coming into Gisborne, at the end of a pivotal day in my rail odyssey, I was feeling exhausted and exhilarated at the same time. I had achieved something I didn’t know was possible and found it to be mind-expanding in a railway sense – and I was hearing snatches of a song which would become the anthem of the era. ‘Love, love, love’ the Beatles harmonised. ‘It’s easy’, John Lennon preached in the lead vocal spotlight. The immediate recognition of a half-remembered song, crackling out of a young woman’s transistor, as the railcar eased off and pulled into Gisborne Station, cemented the memory. As the passengers stirred and shambled towards the exits, the young woman roused and turned her radio off. But I had heard enough. ‘All you need is love.’ Whenever I hear the song it always reminds me of coming into Gisborne as darkness set in, in a railcar that no longer runs, on a day I hoped would never end. I felt as if I’d climbed Everest. ‘There’s nothing you can do, that can’t be done’, John Lennon sang. Maybe. But I wondered how many of my mates would have discovered this way of getting to Gisborne. And how many would have heard ‘All you need is love’ in such a unique, unforgettable setting?

I found a nearby bed and breakfast, intending to catch a bus in the morning. It turned out to be more bed than breakfast. The spread in the morning consisted of burnt toast, cold coffee and some sort of mushed fruit. But the bed had been comfortable although I remained sleepless for a while, as the events of the day rewound in my mind.

You could tell the line to Gisborne had been a tough nut to crack. It wasn’t just the lie of the land, which was often rugged and unstable, but the weather patterns as well. Tropical cyclones were prone to dump their rain load over the Poverty Bay region, and in later years Cyclone Bola wreaked havoc. Miraculously no lives were lost. This wasn’t the case in 1938, when three or four days of torrential rain led to serious flooding. On the night of 19 February, a flash flood inundated a railway workmen’s camp at Kopuawhara. Most of the temporary accommodation was swept away and 22 lives were lost.

The railcar had crossed the Kopuawhara Viaduct just north of Opoutama, or just before the line went walkabout and, unaccompanied by any road, found its way to Beach Loop before linking up with Bartletts and Muriwai. Just another unique feature of the Gisborne line – it had a mind of its own.

The novelty of seeing Wairarapa and Hawke’s Bay for the first time by rail had been a delightful entrée, but the long haul from Napier to Gisborne was a serious, memorable journey. The gaping valleys and massive viaducts, the towering ramparts and sheer cliffs, even the pronounced erosion at certain junctures, made the line unique. Then there were the ocean aspects with the railcar either providing spectacular elevated views, or virtually running along the beach at places like Opoutama. The land might be moving in some places but while it was still there it made for a wondrous rail setting.

‘Don’t take this train for granted,’ was the title of an obscure New Zealand train song. It could have been written specifically about the Gisborne railcar, one of New Zealand’s most underrated rail journeys.

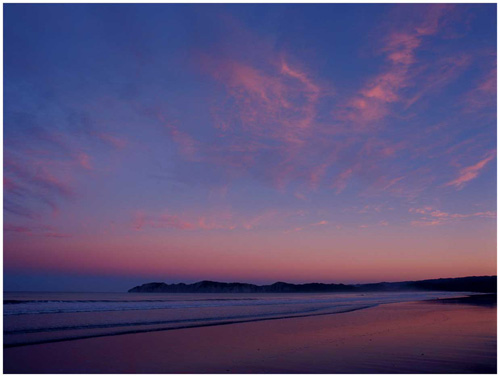

‘Are you going all the way to Gisborne?’ Pam had asked me as the railcar came out above the ocean at Beach Loop. The breadth of the Pacific and the depths of its blues took your breath away. So much so that I forgot to reply.

‘Oh, it’s just the sea, for goodness sake,’ Pam snapped. ‘You get sick of it after a while...’

Gisborne might have been the end of the line in 1967, but for many years there was an expectation that this was just part of the continuum. The line was to have carried on – and on – until it linked up with the Bay of Plenty line. Bearing in mind the latter got as far as Taneatua, that became the beacon destination, although alternate routes had been proposed, or even promised by local government and politicians of every colour.

Politicians. As delays, depressions and wars interceded, politicians continued to woo the people of Poverty Bay with assurances of a connecting line which would one day make it possible to travel by rail from Wellington to Auckland via a continuous east coast trunk line.

Despite the rugged landscape confronting engineers and line builders, hopes remained high. You could say the refinement of motor transport displayed bad timing. Politicians started duck shuffling when they began to sense an out – they could always point to the growing sophistication and clamour for buses, trucks and cars, as a worthy reason for procrastinating about an expensive railway line.

It was even suggested the railways shot themselves in the foot. In constructing rough roads to access rail construction sites they laid down much of the groundwork for roadworkers to follow in their wake, causing politicians to ponder less and less about the need to budget for rail expansion through the God-awful hills on the way to the Bay of Plenty.

That may have been an ironical touch but the biggest irony lay stretched out as far as the eye could see, northwest of Gisborne. Since 1917 the Moutohora Line had been in operation as a functional branch. The irony of the iron, the champions of expansion sighed, as the idea of extension beyond Moutohora slipped off the drawing board.

It’s a funny feeling thinking you’ve made a remarkable discovery in a rail sense, only to realise the back story of Moutohora diminished your own sense of relishment. There may have been a rail buff on an earlier odyssey, who arrived in Gisborne on 14 March 1959, with intentions of travelling further north, only to find the Moutohora branch closed that very day.