ALMOST THERE

May marks the return to the farmers’ market where my season begins with selling vegetable and herb plants, freshly cut perennial herbs, and overwintered crops like leeks. Engaging with customers, I get to hear a range of garden plans, from potted tomatoes on patios to nearly subsistence-size gardens. It is so rewarding to be a part of these gardening journeys, to hear about last year’s successes and the goals for this season. During this same period, the birds, mammals, and insects quickly move from brooding their young to feasting on nature’s abundance. We think we are growing our gardens for ourselves, but the rest of nature is pretty sure we are growing it for them! Get your defense strategies in line, continue growing or purchasing plants, keep weeding, pound in those stakes, and have your sunscreen handy: summer is almost here.

PLAN

■ Make sure your kitchen is ready for the coming onslaught of vegetables, and start reading cookbooks in earnest

■ Keep up with your journal, adding information about pests and disease

PREPARE AND MAINTAIN

■ Continue to maintain transplants; thin out to recommended spacing

■ Remove row covers as needed so plants don’t overheat under plastic

■ Look for signs of pests and disease and protect plants

■ Install and keep up with trellising

■ Weed, weed, weed

■ Ready your watering system. May can sometimes have dry spells that are detrimental to newly planted seeds.

SOW AND PLANT

ZONES 3 AND 4

■ Start seeds indoors (early in month): cucumbers, lettuce, melons, summer squash, tomatoes, and winter squash

■ Direct sow: arugula, beans, beets, bok choy, carrots, corn, cucumbers, kale, kohlrabi, lettuce, melons, peas, radishes, salad greens, spinach, Swiss chard, and turnips

■ Transplant: basil, bok choy, broccoli, Brussels sprouts, cabbage, cauliflower, celery and celeriac, frisée, kale, kohlrabi, leeks, lettuce, onions, radicchio, scallions, shallots, and Swiss chard

ZONES 5, 6, AND 7

■ Be prepared to cover frost-sensitive crops in the event of an unseasonable frost

■ Direct sow: beans, corn, cucumbers, lettuce, melon, summewr squash, and winter squash

■ Transplant: basil, celery and celeriac, eggplant, melons, peppers, summer squash tomatoes, and winter squash

HARVESTING NOW

Arugula Chives Fava beans Kale Lettuce Parsley Radishes Rhubarb Salad greens Scallions Spinach Swiss chard

Dealing With Pests and Disease

As your garden begins to fill in and your vegetables start maturing, you will notice more evidence of pests and diseases. I hope that you will not encounter any major issues, but know that they are sometimes inevitable and out of your control. Although it can be tempting to fall into a “war on pests” mindset, a more holistic approach tends to produce better results. I try to refrain from going directly after the problem, and instead consider what circumstances allowed the problem to develop. A serious slug population, for example, points to an environment with too much moisture and not enough air movement, which is especially common in smaller jam-packed gardens. In fact, excessive moisture and lack of air movement leads to many problems, particularly mildew and other moisture-loving diseases.

Even with an observant holistic approach, you will experience outbreaks and emergencies. My general philosophy falls in the order of prevent, release, and spray. First, do everything you can to prevent an outbreak. If you have had issues in the past with certain pests, release beneficial insects. If all else fails and you are going to lose the crop, spray.

Prevent

Methods of prevention include having a diverse ecosystem around your plants, keeping pots and trays clean, not bringing diseased or insect-infested plants into your garden, moderating water used to irrigate, amending your soil properly so it can feed the plants well, and planning enough space in the garden for good air movement. Covering young plants with Reemay will also help protect them from flea beetle damage. Flea beetles eat tiny holes in young tender vegetation; when there are enough holes, the plant can no longer photosynthesize, and expires. Row covers will also keep out cucumber beetles, potato beetles, and even aphids. A few tips for using Reemay:

1 Cover plants as soon as they are planted or seeded; you don’t want to trap pests in after they have arrived.

2 Pull the edges and ends taut to prevent insects from getting in.

3 For flowering crops that need pollination, remove the cover when flowers appear. At this point the plants should be mature and healthy enough to handle some insect pressure.

4 You can use Reemay with or without the hoop system because the material is breathable and light enough to lie directly on top of plants. Just make sure you loosen it as the plants grow.

Release

I love releasing beneficial insects. Not to delve too deeply into battle metaphors, but releasing insects feels like giving the losing army a mess of fresh new soldiers. Some beneficial insects that I’ve used include colemani parasitic wasps, ladybugs, lacewings, and praying mantis. Colemani parasitic wasps lay their eggs on the bodies of aphids. As the eggs mature into larvae, they eat the aphids from the inside out, leaving thin shells in their place. These wasps occur in nature, but not usually in large enough numbers to take care of an aphid outbreak, so I bring in reinforcements. Lacewing larvae eat aphids, small beetles, scale insects, leafhoppers, thrips, small flies, and mites; they will even eat each other, but I hope that is accidental. Ladybugs are also particularly useful in eradicating aphids, along with other soft-bodied insects like mites and white fly. The praying mantis plays a slightly different role because beyond being particularly fond of grasshoppers, it is not selective. It will eat everything in its way, including your beneficials. But if the pests are bad enough, it may help bring things back into balance.

Spray

If all the prevention and releasing fails, the final tool to combat a serious problem is spraying. In the world of organic growers even using the word “spray” is antithetical because of the strong association with spraying harmful chemicals and the perception that you failed in some way to prevent the outbreak. Although I recommend it only as a last measure, spraying can be an important part of the solution. As organic growing has gained in popularity and continues to evolve, more and more options are available. Always handle products with care, read the warnings, and follow all instructions. Also try not to spray right before it rains as most insecticides require ingestion and don’t kill on contact. Some sprays that have worked for me include:

Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt): This naturally occurring bacteria interrupts the digestive functioning of the insect. It is harmless to humans but kills the insect in a few days. It must be ingested so apply thoroughly. I have had great success with Bt on cabbage worm infestations.

Pyrethrin: This naturally occurring pesticide (derived from chrysanthemum plants) is toxic to many insects including aphids, earwigs, and thrip. I have had mixed success with pyrethrin, but I’ve found a newer version called PyGanic to be more effective.

Diatomaceous earth (DE): Made from ground-up fossilized shells, DE is extremely sharp on a microscopic level. To small soft-bodied insects it feels like walking on knives, but to us it is as soft as flour to the touch. As insects move through DE they slowly dry out from the abrasions. To apply, put some in a cup, take a pinch with your fingers, and dust the plants; if possible, apply some on the underside of the leaves too, which is where a lot of pests reside.

Fungicides: Hydrogen peroxide and copper hydroxide will treat fungus, blight, and other bacteria—and both are acceptable for organic gardening. One challenge of fungal and bacterial diseases is that they spread through spores in the air, so make sure you apply weekly until you see results. Hydrogen peroxide is inexpensive and available from any drugstore. It is sold as a 3 percent solution; either use straight or dilute down as low as 1 percent. Copper hydroxide is commonly used on tomatoes to fight various blight problems as well as downy mildew, which shows up as a white film on the plants. Intersperse usage with hydrogen peroxide to reduce likelihood of the disease developing a resistance.

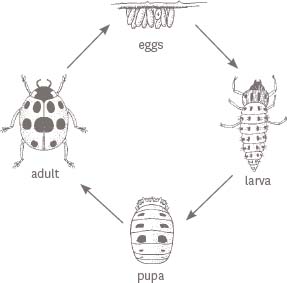

The lifecycle of the ladybug: beloved beneficial queen of the garden.

Fencing

Consider building a fence around your garden if deer, rabbits, and other four-legged furry pests are posing serious problems. Smaller pests, like rabbits and groundhogs, can’t well jump or climb, so a 3- to 4-foot-tall fence should keep them out without impeding your garden access. However, to stop them from digging under you must bury 6 to 12 inches of the fencing material below the surface of the soil. Rolls of chicken wire and galvanized hardware cloth are fairly inexpensive and easy to use. Near where the fencing is sold you’ll find metal stakes that you can tie the fence to for support.

TIPS FROM THE FARMERS’ MARKET

May is a good time to buy plants at your local farmers’ market. It is a great way to get into the habit of going to market, and farmers can provide you with excellent growing tips. As you shop, ask a lot of questions about the particular varieties and how the plants were grown. Remember that not all plants are created equal. Many growers use tools and tricks to grow in a greenhouse that make the plants look good on display, but will reduce your chances for success. Greenhouse-grown plants can be root-bound, over-fertilized, or stressed from inconsistent water. You want to start with the best plants for your garden so inspect plants closely, purchase plants from a grower you trust, and be picky.

If your problems are of a larger nature, you’re not alone. Deer continue to move into heavily populated areas in greater numbers and they’ve been a problem on my farm from the beginning. Fences around your garden need to be at least 8 feet tall in order to discourage deer from jumping over them. The good news is that the fence doesn’t necessarily need to be expensive or permanent; even netting at the appropriate height will make a difference.

Because I kept sheep on the farm, I decided to use the same electric fence system for deer, which included flexible net fencing and a portable fence charger. At the first sign of deer damage, I would move the fence to the critical area. For larger areas, I used two wires instead of the flexible net, one about 18 inches high, and another 40 inches high, approximately the height of the chest of a deer. I would pound in metal posts at the corners, and just enough posts along the sides to keep the wire from sagging. The idea is to make it relatively painless to set up and take down. Once the deer bump into the fence they will become wary. If they get shocked once they will not go near it. Even the wires alone may work because the deer will run into it, get confused, and stay away—at least for a while.

WEED BARRIERS IN THE GARDEN

Landscape cloth and landscape fabric: You can find these materials at hardware or home improvement stores and they usually comes in a few different widths and lengths. Longer-lasting landscape cloth is made of woven strands of poly, which gives it lots of strength; landscape fabric is made from spunbond poly, which easily tears. Water easily gets through landscape fabric so you will likely need to replace it after a few years. To use either fabric or cloth, unroll the material along the length of your bed and lay out where you want your plants. Use scissors to cut 4-inch holes in the material (the holes should be big enough to trowel out the soil and plant). Since landscape cloth is woven, I recommend singeing the edges of the holes with a wand lighter to keep the cloth from unraveling. Secure the material with garden staples or bury the edges. Now you are ready to plant.

Agricultural plastic mulch: This material comes in different colors, widths, and lengths. The most common is 4-foot-wide black plastic. I have tried some of the other colors—such as green (more warmth in the spring), red (for tomatoes), blue (for melons), white on black (for cool-weather crops; the white on top reflects the sunlight), and silver on black (to reduce aphids)—but I am not sure how much of a difference they make. The basic black agricultural plastic mulch is intended for tomatoes and other crops that will appreciate the increased soil temperature created by the plastic; it is not recommended for crops like broccoli and cabbage that prefer cooler temperatures.

Pick a day with low winds and unroll the plastic along the length of your bed. Dig a 4- to 5-inch trench the width of the plastic on both short ends and bury the edge of the plastic. On the sides, use a shovel and dig 4 to 5 inches down, just under the edge of the plastic. Take the soil you dig out and deposit it on top of the edge of the plastic. Slowly work your way down one side and then the other. You may have to kneel down occasionally and pull the plastic tight as you deposit the soil. Next, place your plants, make holes for them with a trowel or scissors, and plant away.

Organic materials: Straw mulch is easy to use and will contribute organic material to your soil as it breaks down. It tends to keep the soil cooler so use it on peas and other cool-weather crops (and for overwintering) rather than on heat-loving crops. Before spreading the straw mulch, make sure the area is hoed and weed-free, and wait until plants have matured a little so you don’t accidently cover them. Starting with a 6-inch-deep layer will ensure that light doesn’t get through and encourage weeds to germinate. After a few weeks this layer will compact down to 3 to 4 inches and create a nice mat. To avoid bringing problems into your garden, select straw that hasn’t been sprayed with chemicals (residual herbicides will reduce the growth of nearby plants) and that doesn’t have too much grain or weeds left in it.

Wood chips, grass clippings, compost, bark, leaves, pine needles, sawdust, and grass are other possible organic materials—I have even seen a gardener use old church bulletins as paper mulch! Be creative and resourceful. Just make sure you don’t bring in any unwanted chemicals. Also, if a lot of your organic mulch is “brown,” use extra nitrogen fertilizer to make up for the loss that occurs as those materials break down. Wood chips, especially, absorb a lot of nitrogen until fully broken down.