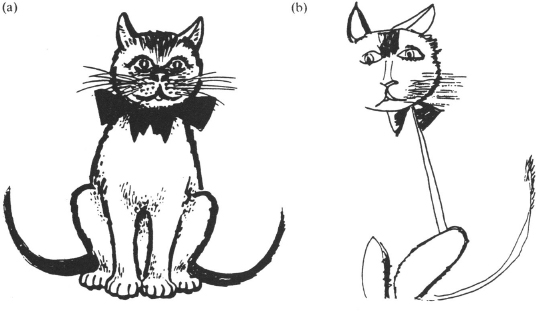

Fig. 1.1 (a) Stimulus (cat); (b) patient’s copy.

The History and Clinical Presentation of Neglect

Rivermead Rehabilitation Centre, Oxford, UK

Neuropsychology Unit, Radcliffe Infirmary, Oxford, UK

Classical visual neglect is one of the simplest of clinical observations and yet one of the most striking. The fact that textbooks are already full of drawings of daisies and clock faces by neglecting patients makes it no less impressive when you first observe it for yourself (Latto, 1984).

What is Neglect?

Of the many neuropsychological consequences that follow right hemisphere brain damage, few are as striking or as puzzling as when a patient without impairment of intellectual functioning appears to ignore, forget or turn away from the left side of space—as if that half of the world had abruptly ceased to exist in any meaningful form (Mesulam, 1985). This “cognitive” inability to respond to objects and people located on the side contralateral to a cerebral lesion is usually known as unilateral neglect.

The condition can be distinguished from the behaviour associated with primary sensory and motor deficits (hemianopia and hemiplegia), although differential diagnosis may be difficult in the acute phase (Heilman, Watson, & Valenstein 1985b). Most of the classical behaviours associated with the diagnosis of neglect cannot be readily explained in terms of sensori-motor deficits: neglect is manifest in free vision and under conditions of testing that do not necessarily require the use of the motorically impaired limb. Although many patients do have visual field cuts and hemiplegia, severe neglect can be seen in cases without such deficits (Halligan, Marshall, & Wade, 1990). The lesions which produce neglect are not limited to the accepted primary sensory or motor areas. In addition, many neglect behaviours often resolve sooner than those which result from lesions of sensory or motor cortex (Friedland & Weinstein, 1977).

Even a cursory examination of the neglect patient’s behaviour suggests that the spatial disorder underlying the condition is conceptually different from what might be expected to follow impairment of basic sensory or motor abilities. Such deficits do not of themselves entail the failure to explore or respond to objects and activities on the affected side of space (Bisiach, Capitani, Luzzatti, & Perani, 1981). Patients with florid neglect often demonstrate a specific lack of awareness and behave as if they were selectively ignoring stimuli on the impaired side. The condition is more appropriately conceptualised as a failure of looking and searching rather that of seeing or moving the eyes per se (Mesulam, 1985).

Patients often believe that they have an appropriate representation of their environment and consequently additional problems of denial and minimisation of deficit emerge (Gordon & Diller, 1983). In such patients, unawareness of the deficit appears to be a central feature of the condition. This subjective lack of awareness (anosognosia) creates additional difficulties for the patient’s recovery and involvement in rehabilitation programmes. Unawareness of hemianopia and of hemiplegia are often found acutely after brain damage. Levine (1990) suggests that the underlying pathology “is not associated with any immediate sensory experience that uniquely specifies the defect”. Hence, he argues, the loss “must be discovered by a process of self-observation and inference”. It is possible that neglect may similarly need to be discovered by the patient, although the appropriate compensatory reaction is not clear as in the case of hemianopia. Other patients may show unilateral hallucinations restricted to (non-neglected) right hemispace (Chamorro et al., 1990; Mesulam, 1981), phenomena that further confuse the patient’s relationship with reality.

A Brief History of Visual Neglect

The first clinical descriptions of neglect, in the second half of the last century, attracted intense speculation from those few neurological researchers

… who needed a respite from the intricacies of aphasic localization and classification, and wondered how the other half of the brain lived. The manifestations of hemi-inattention have also excited the imagination of those who marvelled that one could exist in a demi-world where laterality determined reality (Weinstein & Friedland, 1977).

Although left neglect is one of the most striking consequences of damage to the right hemisphere, it did not initially receive the attention given to rarer perceptual disorders such as the object agnosias. One reason for this “neglect” of visual-spatial disorders is that, unlike language or figural perception, the structure of psychological space is elusive and difficult to characterise in a precise way (Delis, Robertson, & Balliet, 1985). The very fact that the spatial components of perception are an intrinsic aspect of every visual cognition appears to hinder the scientific appreciation of space (De Renzi, 1982). Evidence of this difficulty can be seen from the diversity of terms that have been used to describe neglect: neglect of the left half of visual space (Brain, 1941); unilateral visual inattention (Allen, 1948); unilateral spatial agnosia (Duke-Elder, 1949); imperception for one half of external space (Critchley, 1953); amorphosynthesis (Denny-Brown & Banker, 1954); left-sided fixed hemianopia (Luria, 1972); hemi-inattention (Weinstein & Friedland, 1977); hemi-neglect (Kinsbourne, 1977); unilateral neglect (Hecaen & Albert, 1978); hemi-spatial agnosia (Willanger, Danielsen, & Ankerhus, 1981); contralesional neglect (Ogden, 1985); dyschiria (Bisiach & Berti, 1987) and directional hypokinesia (Coslett et al., 1990).

Studies of visual neglect can be divided into two periods: (1) early case studies and (2) later, more detailed case series and group studies. The former illustrate some of the difficulties encountered by clinicians attempting to formulate a coherent description of the condition. The majority of these studies fall within the framework of clinical neurology and emphasise neuroanatomy and pathology. The latter attempt to describe the range and types of visual neglect, using a wide variety of operational definitions, clinical tests and pathogical groups.

Hughlings Jackson’s single case report of 1876 is among the first well-documented accounts of neglect. The collective term “imperception” was used to refer to a patient with topographical disorientation, visual neglect, dressing apraxia and some signs of dementia. Jackson noted that when asked to read the Snellen visual acuity chart, the patient “... did not know how to set about [and] began at the right lower corner and tried to read backwards”. Other phenomena mentioned include what would now be termed neglect dyslexia (Ellis, Flude, & Young, 1987): the omission or substitution of letters at the beginning of words. The location of the lesion in the posterior part of the right temporal lobe appeared to confirm Jackson’s earlier intuition (1874) regarding the “leading” role of the right hemisphere in visuo-spatial processes. It should be added, however, that this case is far from representative of the condition: Jackson’s patient demonstrated many other symptoms not intrinsically related to neglect.

Visual neglect was also described at about this time by several German neurologists, but typically only as a minor symptom within a more complex neurological condition. Anton (1883) reported four patients, two of whom, after right-sided lesions, could not perceive passive movements of their left limbs, and ignored what was happening in left extrapersonal space. An early case of neglect dyslexia (with associated anosognosia) was published by Pick (1898) and, in 1909, a patient who made similar reading errors was described by Balint. In this latter case, neglect dyslexia was found in the more general context of “psychic paralysis of gaze, optic ataxia and spatial impairment of attention” (Balint’s Syndrome). In 1913, Zingerle published a case study of a 45-year-old man with hemiplegia, hemianaesthesia and hemianopia following right hemisphere stroke, whose neglect involved both personal and extrapersonal space. Zingerle’s distinctive contribution (see Bisiach & Berti, 1987, for an appraisal) was his subsequent analysis, which classified the patient’s condition as similar to the “dyschiria” which had been described earlier by Jones (1910) in the case of a patient who had a specific impairment in the appreciation of left-sided personal space despite intact sensory abilities.

Holmes and Poppelreuter

The First World War resulted in large numbers of young soldiers with relatively discrete cerebral lesions. Examination of these men and, in particular, the systematic work of Walter Poppelreuter and Gordon Holmes, led to significant insights into the factors that underlie the complex syndrome variously described as “visuo-constructive” or “visuo-orientational” disability. In discussing the condition of “visual disorientation” or “defective spatial orientation”, Holmes (1918) made a critical distinction. Whereas before “visual disorientation” was regarded as primarily a manifestation of visual agnosia, it was now possible to show that visual disorientation could occur without “object agnosia”. This distinction subsequently provided the basis for a re-examination of the concept of “visual inattention”.

Gordon Holmes’ concept of “inattention” was similar to that of Poppelreuter (1917), which for the most part described the elicited response of “extinction” rather than the spontaneous manifestations of visual neglect. This emphasis on extinction was not altogether surprising, since florid symptoms of visual neglect are not typically found after focal penetrating lesions (Kinsbourne, 1977; Mesulam, 1985). Extinction refers to the following situation with fixed gaze: when visual fields are assessed by presentation of a single object (e.g. the clinician’s finger), detection appears normal, i.e. both left and right fields are “full to confrontation”. However, when two objects are presented at the same time, one in each field, only one of the stimuli is reported. This latter finding is known as “extinction to double simultaneous stimulation”. Holmes reports, however, that similar effects can be seen in situations other than conventional visual field testing. For example (Holmes & Horrax, 1919):

When asked to look at a needle placed on the table, he [the patient] often failed to detect a pencil placed on one side of it, or if there were two pencils, he could only see the one or the other. At one time ... while sitting in the ward, it was noticeable that the patient usually saw only what their eyes were directed on and that they took little interest in what was happening around them (Holmes. 1919) … attention lacked its normal spontaneity and facility in diverting itself to new objects.

Although both Holmes and Poppelreuter alluded to what may be regarded as neglect behaviours, many of their systematic investigations concerned the failure to attend to peripheral stimuli approaching from one side when stimuli from both sides were presented. Poppelreuter (1917) describes how such phenomena may result from an “organic weakness of attention”. The “only possibility of differentiating between hemi-inattention and a ‘perceptive’ hemianopia”, he writes, is to attempt to re-orient attention by actively directing the patient’s attention to the “neglected” side. Poppelreuter also emphasised that no explanation of heminattention can ignore the apparent “completion” of simple forms when a segment thereof falls within a “blind” or neglected area: “the totalizing apperception of form is thus capable of compensating considerably for hemianopia as well as for unilateral weakness of attention” (Poppelreuter, 1917).

Like Poppelreuter, Holmes’ description of “inattention” goes further than the elicited response of “extinction” and may more accurately be described as a “limitation of visual attention to those objects within the central vision” (Weinstein & Friedland, 1977). Some of these cases would now be described under the label “simultanagnosia”. Describing one such case, Holmes and Horrax (1919) wrote:

It is essentially a disturbance of visual attention; retinal impressions no longer attract notice with normal facility, and if two or more images claim attention, this is liable to concern itself exclusively with, and to be absorbed in, that which is at the moment in macular vision …

For Holmes, “inattention” was only one of several component features that contributed to a major disturbance of visual orientation. On several occasions, Holmes goes so far as to point out that inattention per se is not an essential part of the condition, and may often occur independently of problems with visual orientation (Holmes, 1918; 1919; Holmes & Horrax, 1919). Holmes’ analysis of inattention originated within a general evaluation of visual disabilities after predominantly bilateral damage. It is not clear that the concept of unilateral (contralesional neglect) was available to him.

The term “neglect” was first used consistently by Pineas (1931). Pineas described a 60-year-old woman whose vernachlassigung (neglect) of the left side was both severe and long-lasting, despite the absence of a field deficit or sensori-motor loss. Pineas concluded that the left half of the body schema and extrapersonal hemispace did not exist for the patient in any meaningful way. Although Holmes (1918), Poppelreuter (1917), Pineas (1931) and Scheller and Seidmann (1931) documented some of the behavioural features of visual neglect and suggested an attentional explanation, it was not considered a specific syndrome until the Second World War and the work of Russell Brain. Brain’s article in 1941 was the first report that isolated and characterised some of the main features of visual neglect.

Brain (1941): A Seminal Paper

Brain’s (1941) article remains an important milestone in the conceptualisation of neglect as a distinct neurological condition. Brain set out to provide a coherent sub-classification of the syndrome commonly referred to as “visual disorientation”. As a clinical description, Brain recognised that the term had become a “loose and comprehensive description covering a number of disorders of function differing in their nature”. Although the article lists nine different features, the main classification distinguished between “defective localisation of objects” and what Brain described as “agnosia for the left half of space”.

Three cases of each disorder were presented. In the second type, the patients ignored the left side of space, and thus among other peculiarities tended to make inappropriate right-sided turns while following familiar routes. All three patients had large right parieto-occipital lesions and left visual field deficits.

Brain’s subsequent analysis is one of the first attempts to describe and explain visual neglect in terms of a disturbance of perceptual space. The main conclusions of the article, which served as the basis for many subsequent investigations, included: (a) indicating a strong association with posterior lesions of the right hemisphere; (b) demonstrating the inadequacy of a purely sensory explanation—visual neglect could not be attributed to a visual field deficit; (c) distinguishing between “visual inattention” and visual neglect; and (d) suggesting that the condition should be distinguished from topographical memory loss, visual agnosia and left-right discrimination problems.

On the question of underlying mechanisms, Brain resurrected the old physiological concept of body schema, which had been used by Head and Holmes (1911) and Zingerle (1913) and which was later incorporated into a psychoanalytic framework by Schilder (1935). As pointed out by Friedland and Weinstein (1977), the concept of body schema was important in that it linked personal and extrapersonal space and emphasised yet again that neglect could not be explained in terms of hemianopia. For Brain (1941):

... the patient’s behaviour towards the left half of external space is similar to the attitude adopted towards the left half of the body. Since each half of the body is a part of the corresponding half of external space, it is not surprising to find that perception of the body and perception of external space are closely related.

Although the notion of a disruption of the body schema has provided the basis for several attempts to explain perceptual disturbances that relate to personal space (Roth, 1949), the extension of the concept to include disorders of extrapersonal space raises several problems (McGlynn % Schacter, 1989). None the less, Bisiach et al. (1981) suggest that the concept of body schema together with that of “representational space” offer one of the few realistic attempts to explain neglect. The chief difficulty with earlier accounts, Bisiach et al. (1981) argue, stemmed from the fact that “they generally misused the concept of schema to describe a set of disorders, rather than arguing its necessity as an explanatory concept”.

Since Brain’s (1941) report, investigations of visual neglect have proliferated, both within the tradition of clinical neurology and more recently within neuropsychology (Battersby, Bender, Pollack, & Kahn, 1956; Critchley, 1953; De Renzi, Faglioni, & Scotti, 1970; Faglioni, Scotti, & Spinnler, 1971; Gainotti, 1968; Hecaen, 1962; Heilman, Valenstein, & Watson, 1985a; Oxbury, Campbell, & Oxbury, 1974; Piercy, Hecean, & Ajuriaguerra, 1960; Zarit & Kahn, 1974).

Zangwill (1944–60): The Development of Testing Procedures

Between 1944 and 1960, what may be described as “Zangwill’s group” (Ettlinger, Warrington, & Zangwill, 1957; Humphrey & Zangwill 1952; McFie & Zangwill, 1960; McFie, Piercy, & Zangwill, 1950; Patterson & Zangwill, 1944, 1945) was particularly productive.

In their initial two papers of 1944 and 1945, Patterson and Zangwill employed for the first time a wide variety of verbal and visuo-constructive tasks designed to assess their patients’ visuo-spatial disturbances. These included the use of clock drawing, pointing tasks, spontaneous drawing and copying, and were intended to further refine the concept of visuo-spatial disorientation. Patterson and Zangwill (1944) showed a dissociation between personal and extrapersonal neglect, thus questioning Brain’s original contention that a strong association existed between visual neglect and a disturbance of the body schema. They pointed out the effects of stimulus complexity, and also confirmed the variable effect of neglect on many everyday activities. In a subsequent paper, McFie et al. (1950) showed how drawing a scene can dissociate from a verbal description thereof. A 55-year-old master printer manifested difficulties representing the ground plan of his home, while at the same time being able to describe verbally the layout accurately and in detail. Critchley (1953) also showed how neglect could be seen on simple copying and drawing tasks. Ettlinger et al. (1957) demonstrated the need to consider environmental rather than retinopic co-ordinates in the explanation of neglect; they showed that visual neglect persisted even under conditions in which the patient is forced by optokinetic nystagmus to fixate the object in the left half of extrapersonal space. In their view, the essential deficit lay not at the level of sensory input, but in a failure to make effective use of this input at a more central level. They also argued that there was no necessary relationship between visual neglect and visuo-constructional disorders.

Re-emergence of Interest in Visual Neglect: 1970–1993

The last two decades have seen a phenomenal increase in the number of studies of neglect phenomena (Bisiach & Vallar, 1988; De Renzi, 1982; Heilman, Watson, & Valenstein, 1985a; Jeannerod, 1987; Mesulam, 1985; Prigatano & Schacter, 1991; Riddoch, 1991; Weinstein & Friedland, 1977). This growth of interest is partly due to the potential significance of neglect for theories of normal spatial processing (Delis et al., 1985; Jeannerod, 1987), selective attention (Posner & Rafal, 1987), mental representation (Bisiach & Vallar, 1988; Farah, 1989), awareness (Levine, 1990; McGlynn & Schacter, 1989), and pre-motor planning (Rizzollatti & Camarda, 1987; Tegner & Levander, 1991). In addition, the interest of clinicians and therapists has been attracted; neglect can be a major disability in the acute phases of recovery from stroke and can impede later attempts to rehabilitate the patient (Denes, Semenza, Stoppa, & Lis, 1982; Diller & Weinberg, 1977; Kinsella & Ford, 1980).

From a neuropsychological perspective, neglect today provides a fascinating window on the spatial processes and attentional mechanisms that underlie normal cognition (Bisiach & Berti, 1987). It is now generally accepted that neglect is a disorder which can compromise several modalities and may involve personal, peripersonal, extrapersonal and representational space (Bisiach & Luzzatti 1978: Halsband, Gruhn, & Ettlinger, 1985; Meador, Loring, Bowers, & Heilman, 1987; Rizzollatti & Gallese, 1988). None the less, the condition is far from unitary and can fractionate into a number of dissociable components in terms of sensory modality, spatial domain, laterality of response, motor output and stimulus content (Bellas, Novelly, Eskenazi, & Wasserstein, 1988; Bisiach, Geminiani, Berti, & Rusconi, 1990; Bisiach, Perani, Vallar, & Berti, 1986; Caplan, 1985; Colombo, De Renzi, & Faglioni, 1976; Costello & Warrington, 1987; Cubelli et al., 1991; Daffner, Ahern, Weintraub, & Mesulam, 1990; De Renzi, Gentillini, & Barberi, 1989; Fujii et al., 1991; Gainotti et al., 1986; Halligan, Manning, & Marshall, 1991b; Halligan & Marshall, 1991; Laplane, 1990; Tegner & Levander, 1991; Young, de Haan, Newcombe, & Hay, 1990).

Recent evidence suggests that the “left” in left neglect may involve several different reference systems, including retinal, head, trunk and gravitational co-ordinates (Bisiach, Capitani, & Porta, 1985; Bradshaw, Pierson-Savage, & Nettleton, 1987; Calvanio, Petrone, & Levine, 1987; Karnath, Schenkel, & Fischer, 1991; Ladavas, 1987). Kinsbourne (1977) has argued that the traditional dichotomising term “hemispatial neglect”, which only took account of performance relative to the mid-sagittal plain, is misleading. Rather, there is a gradient across space (Marshall & Halligan, 1989), such that attention is biased away from the left, regardless of the absolute location of the stimulus within the visual field (De Renzi et al., 1989; Kinsbourne 1970; See also Chapter 3, this volume). Patients with neglect often direct their attention to the right-most features of a configuration, even when the entire stimulus is located in the right (intact) visual field (De Renzi et al., 1989).

Further complexities become apparent when one considers reports of word- and object-centred neglect (Caramazza & Hillis, 1990; Driver & Halligan, 1991; Gainotti, Messerli, & Tissot, 1972; Ogden, 1985; see also Chapter 11, this volume). The manifestations of neglect can often be modulated by the overall visual configuration of the stimulus array (Halligan & Marshall, 1988, 1991; Kartsounis & Warrington, 1989; Seron, Coyette, & Bruyer, 1989). These findings suggest that the deployment of attention is influenced by the perceptual parsing of configurations in the non-neglected field. Likewise, “top-down” phenomena are seen in the differential effects of neglect on word and nonword reading (Behrmann, Moscovitch, Black, & Mozer, 1990; Kinsbourne & Warrington, 1962). It is also clear that, in some patients, stimuli in the “neglected” field, while unavailable to “consciousness”, may none the less influence responses to stimuli in the non-neglected field (Audet, Bub, & Lecours, 1991; Berti & Rizzolatti, 1992; Karnath & Hartje, 1987; Marshall & Halligan, 1988; Sieroff, Pollatsek, & Posner, 1988; Spinelli et al., 1990; Volpe, Le Doux, & Gazzangia, 1979).

Clinical Presentation of Visual Neglect

Neglect is commonly seen after stroke or neoplasm; it is often transient with the most conspicuous manifestations in many cases lasting no more than a few weeks (Friedland & Weinstein, 1977). The condition is frequently found in association with a constellation of sensori-motor deficits, including visual field cuts and hemiparesis.

Most reported cases of severe and persistent neglect involve right hemisphere lesions (Critchley, 1953; Hecaen & Albert, 1978; Weintraub & Mesulam, 1988). This apparent asymmetry in presentation has been questioned on the grounds of subject selection, e.g. the exclusion of left hemisphere cases where dysphasia seriously impairs comprehension (Ogden, 1987). However the issue has been addressed by studies which employed unselected patients and simple tasks. These studies have shown consistently that left visual neglect is both more frequent and more severe after right hemisphere damage than is right neglect after left hemisphere damage (Bisiach, Cornacchia, Sterzi, & Vallar, 1984; Caltagirone, Miceli, & Gainotti, 1977; Colombo et al., 1976; Fullerton, McSherry, & Stout, 1986; Gainotti et al., 1972; Oxbury et al., 1974).

Studies that find no significant difference in the frequency of neglect between left and right brain-damaged patients (Albert, 1973; Battersby et al., 1956; Ogden 1985) have usually involved patients with tumours as opposed to the majority of neglect studies which involve stroke patients. Unlike stroke patients where the acute manifestations often resolve rapidly, tumour patients generally run a progressive course, complicated by the effects of oedema, compression and the infiltration of neighbouring brain regions (Vallar & Perani, 1987). Recent studies have shown that despite close matching for lesion locations, tumour and stroke patients demonstrate major differences in their respective neuropsychological impairments (Anderson, Damasio, & Tranel, 1990).

Estimates of the frequency of visual neglect differ considerably and depend on the tests and criteria employed (Halligan & Robertson, 1992). Using different cancellation tasks, Diller and Gordon (1981), Vallar and Perani (1986) and Girotti, Casazza, Musicco, and Avanzini (1983) have estimated that the incidence of visual neglect ranges between 40 and 44% after right hemisphere stroke. Using a battery of six different tests in a group of patients who were on average 2 months post-stroke, Halligan, Marshall, and Wade (1989) found a frequency of 48% in the right brain-damaged group and only 15% in the left brain-damaged group.

Time post-onset is seldom taken into account when considering the frequency of neglect. Most of the large group studies of visual neglect have recruited patients at different times post-onset. Recently, Stone et al. (1991) showed that when stroke patients were assessed after 3 days, neglect was equally common in patients with right and left hemisphere damage, but by 3 months the relative frequency was far greater in the right brain-damaged group.

Neuropsychological assessment of neglect may be difficult due to the additional presence of constructional dyspraxia, optic ataxia and topographical disorientation. Many manifestations (visual, auditory and tactile) can be readily detected by simply observing the patient’s everyday interactions. However, clinical observations show that neglect may be task-specific (Horner et al., 1989). Patients with visuo-spatial neglect on drawing, for example, may not necessarily demonstrate neglect on reading or writing tasks (Costello & Warrington, 1987).

In the acute phase, neglect is often characterised by a marked deviation of the head, eyes and trunk away from the contralesional field. During neuropsychological assessment, the patient appears to be “magnetically” drawn to those stimuli and activities located on the ipsilesional side. Careful examination of eye movements at this stage often shows that most scanning saccades are restricted to the ipsilesional side of space (Ishiai, Furukawa, & Tsukagoshi, 1979; Rubens, 1985), although the patient may have full extraocular movements to command (Mesulam, 1985). The absence of leftward eye movements during sleep in neglect patients has recently been reported by Doricci, Guariglia, Paolucci, and Pizzamiglio (1991).

In severe cases, patients fail to recognise their contralateral extremities as their own. They may experience difficulties in remembering left-sided details of internally represented familiar scenes (Meador et al., 1987) and in general only attend to events and objects located on the ipsilesional side of space. Consequently, patients can easily become excessively isolated as a result of their neglect. Some patients will shave or groom only the right side of their body. They may fail to eat food placed on the left side of the plate, fill out only the right half of a form, omit to wear the left sleeve or slipper, forget to place the left foot on the wheelchair rest, etc. They may report personal belongings as missing even when the objects are clearly in front of them and often lose their way travelling between hospital departments. When transferring from a wheelchair, such patients may fall because they have failed to stabilise the chair by locking both sides. They often collide with people and objects on the affected side. Many of these patients also manifest difficulties with the spatial aspects of such basic skills as reading, writing, copying and drawing. In general, their spontaneous behaviour is characterised by what appears to be a gross inattention to the left side of space (Adams & Hurvitz, 1963; Critchley, 1953; Halligan & Robertson, 1992; Piggott & Brickett, 1966).

Illustrations of Visual Neglect

Copying

Copying and constructional tasks are among the clearest ways of illustrating the curious and often variable nature of neglect, despite the fact that poor pre-morbid drawing ability and other visuo-motor constructional problems consequent upon lesion may conspire to render some productions difficult to interpret as “pure” illustrations of neglect. The illustrations used in this chapter were selected from a large database that included many poorly organised reproductions.

Figure 1.1 shows an example of the type of deficit found on copying tasks. The patient’s copy of the cat clearly shows left-sided omissions, despite the very reasonable reproduction of right-sided features.

Fig. 1.1 (a) Stimulus (cat); (b) patient’s copy.

Drawing from Memory

When asked to draw from memory, patients are no longer constrained by the sensory features of the stimulus configuration and must depend on previously acquired information.

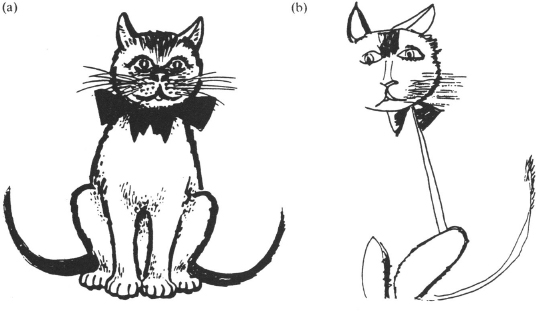

Patients tend to confine their productions to the right side of the page. As in copying, the drawings often include an adequate representation of the right side of a figure with the left side entirely omitted or grossly distorted, despite the fact that the figure may be a well-known symmetrical configuration (such as a clock face), which of itself should implicitly demand the full figure. When asked to draw a clock face from memory, some patients with neglect produce an example such as that shown in Fig. 1.2a. All the numbers on the right side have been positioned in roughly the correct locus. Furthermore, the patient has set the clock hands correctly at two o’clock (as requested) and confirms this in writing at the bottom of the figure.

Fig. 1.2 (a) Stimulus (clock face); (b) neglect on a clock face drawing.

Other patients position all or most of the 12 numbers on the right side of the clock face (Fig. 1.2b). In these cases, the patient appears to have transposed details from the left side of the object over into the right. Although examples of this second type of clock face have been described in the literature (Bisiach et al., 1981), they have occasioned little comment. However, the systematic transposition of left-sided details over onto what has been typically regarded as intact right-sided space, raises more questions than answers. In order to achieve a successful transposition of the left-sided details in Fig. 1.2b, the patient has to alter the spatial arrangement in right-sided space to accommodate the incoming left-sided numbers while retaining (to some extent) their conventional sequence.

The transposition process itself might be described in terms of either sensory allaesthesia (Joannette & Brouchan, 1984) or neglect-related hypokinesis (Bisiach et al., 1990; Heilman et al., 1985b). However, it is difficult to understand why such patients do not notice or comment on the compression and disruption of right-side features that they have themselves produced. In addition, notice that the time setting that the patient has written at the bottom of the clock face also involves the acceptance of the transposed numbers.

One feature of clock drawing that has rarely been mentioned is that the circumference of the clock face is not usually affected. Perhaps the optimal gestalt of the circle precludes the omission of parts thereof. Another interesting feature of both drawing and copying is that some patients selectively neglect the left side of an object, although the right side of a stimulus further to the left is reproduced. Examples of this object-centred neglect have been reported by Gainotti et al. (1972) and Driver and Halligan (1991). A good illustration of object-centred neglect can be seen in Fig. 1.3. Here the patient was asked to copy a complex scene. Although she attempted to copy all the stimuli except the small figure of the woman on the extreme left, her reproduction shows omissions and/or distortions of features from the left sides of objects at different lateral positions across the stimulus array.

Fig. 1.3 (a) Stimulus: (b) “object-centred” neglect.

On reading tasks, the right brain-damaged patient with neglect may fail to read the left part of a word or sentence. Text reading often commences in the central portions of the array (Ellis et al., 1987; Kinsbourne & Warrington, 1962; Riddoch, 1991; see also Chapter 11, this volume). Comparable reading errors involving the right side after left brain damage have also been described (Hillis & Caramazza, 1989; Warrington, 1991; Warrington & Zangwill, 1957). In some patients, neglect dyslexia may be the only obvious form of spatial disorder present (Baxter & Warrington, 1983; Costello & Warrington, 1987).

Most of the errors involve the substitution of letters to form alternative words of approximately the same length as the target. Some of the errors are left-sided deletions, particularly where the resultant residue forms a word in its own right. Table 1.1 lists some examples of neglect dyslexia with single words after left and right brain damage.

Table 1.1

Examples of Neglect Dyslexia in Right and Left Brain Damaged Patients

aFrom Warrington (1991); bfrom Ellis et al. (1987).

Prose reading becomes an arduous chore for the patient, especially when the material is unfamiliar and can provide little meaningful context to compensate for the substitutions and omissions. As in the case of drawing and copying, patients (despite in many cases being able to articulate their problem) fail to cue themselves automatically to the affected side. Sometimes they blame their eyesight, maintain that they have lost interest in reading or claim that the target text was meaningless to begin with.

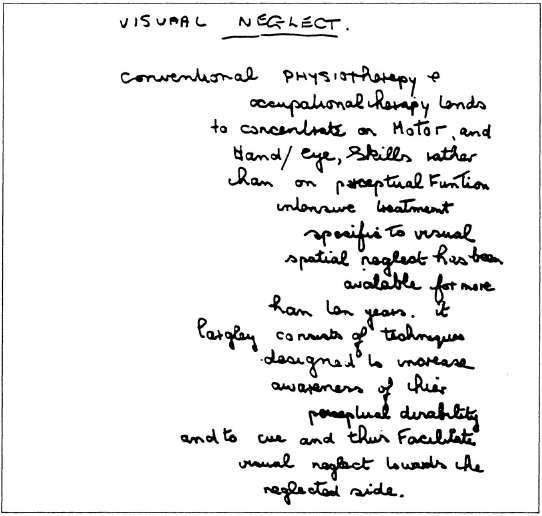

Writing (Neglect Dysgraphia)

Writing may also be affected. The patient may use an uncommonly wide left-sided margin, and hence squeeze most of the text into the right half of the page (Ellis et al., 1987; Hecaen & Marie, 1974; Luria, 1972; Mesulam, 1985). When asked to copy printed or written text, the patient may show selective word or part-word omissions and large spacing errors, in addition to the distinctive crowding of the right side of the page. An example is shown in Fig. 1.4.

Fig. 1.4 Neglect patient’s written performance (dictated passage)

There may also be letter and/or stroke additions and omissions (Ellis et al., 1987; Hecaen & Marie, 1974). In Fig. 1.4, it can be seen that the patient has failed to cross many of her t’s and dot many of her i’s. These omissions have been interpreted by Ellis et al. (1987) in terms of “neglect” of both visual and kinaesthetic feedback.

Conclusions

Although reports of visual neglect were first published in the second half of the last century,

it is a fact (and perhaps a significant one) that the study of (neglect) went through a long period of relative stagnation, until Geschwind (1965), Kinsbourne (1970) and Heilman and associates (Heilman et al., 1985) reawakened interest in this area by demonstrating that it could repay fresh and versatile inquiry (Bisiach & Berti, 1987).

Factors responsible for the relative paucity of neglect research until the early 1970s include the failure to differentiate and characterise the essential spatial features of the condition; the widespread acceptance of inadequate infra-cognitive interpretations; and the absence of theoretical frameworks to guide the design of new experiments. Chapter 13, by Marshall, Halligan, and Robertson, outlines some of the main interpretations of visual neglect. These include accounts that place the primary stress upon sensory, perceptual, attentional and representational factors.

In addition, there was a tendency to move away from the actual phenomena of neglect without having fully explored the many perplexing variations in performance. As Bisiach and Rusconi (1990) suggest, “it might be the case that (paraphrasing Wittgenstein) we find certain aspects of neglect puzzling, because we do not find the whole business of neglect puzzling enough”.

This work was supported by the Medical Research Council, Remedi and the Stroke Association.

References

Adams, G.F. & Hurvitz, L.J. (1963). Mental barriers to recovery from stroke. Lancet, 2, 533–537.

Albert, M. (1973). A simple test of visual neglect. Neurology, 23, 658–664.

Allen, I.M. (1948). Unilateral visual inattention. New Zealand Medical Journal, 47, 605–617.

Anderson, S., Damasio, H., & Tranel, D. (1990). Neuropsychological impairments associated with lesions caused by tumour or stokes. Archives of Neurology, 47, 397–405.

Anton, G. (1883). Beitrage zur klinischen Beurtheilung und zur localisation der Muskelsinnstorungen un Grosshirne. Stschr. f. Heilk., 14, 313–348.

Audet, T., Bub, D., & Lecours, A.R. (1991). Visual neglect and left-sided context effects. Bruin and Cognition, 16, 11–28.

Balint, R. (1909). Seelenlahmung des “Schauens”, optische Ataxic Raumliche Storung der Aufmerksamkeit. Monatschrift fur Psychiatric and Neurologic 25, 51–81.

Battersby, W.S., Bender, MB., Pollack, M., & Kahn, R.L. (1956). Unilateral spatial agnosia (inattention) in patients with cerebral lesions. Brain, 79, 68–93.

Baxter, D. & Warrington, E.K. (1983). Neglect dysgraphia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 46, 1073–1078.

Behrmann, M., Moscovitch, M., Black. S., & Mozer, M. (1990). Perceptual and conceptual mechanisms in neglect dyslexia. Brain, 113, 1163–1183.

Bellas, D.N., Novelly, R.A., Eskenazi, B., & Wasserstein, J. (1988). The nature of unilateral neglect in the olfactory sensory system. Neuropsychologia, 26, 45–52.

Berti, A. & Rizzolatti, G. (1992). Visual processing without awareness: Evidence from unilateral neglect. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 4, 345–351.

Bisiach, E. & Berti, A. (1987). Dyschiria: An attempt at its systematic explanation. In M. Jeannerod (Ed.), Neurophysiological and neuropsychological aspects of spatial neglect. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Bisiach, E., Capitani, E., Luzzatti, C, & Perani, D. (1981). Brain and conscious representation of outside reality. Neuropsychologia, 19, 543–551.

Bisiach, E., Capitani, E., & Porta, E. (1985). Two basic properties of space representation in the brain. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery und Psychiatry, 48, 141–144.

Bisiach, E., Cornacchia, L., Sterzi, R., & Vallar, G. (1984). Disorders of perceived auditory lateralisation of the right hemisphere. Brain, 107, 37–52.

Bisiach. E., Geminiani, G., Berti, A., & Rusconi, M. (1990). Perceptual and premotor factors of unilateral neglect. Neurology, 40. 1278–1281.

Bisiach, E. & Luzzatti, C. (1978). Unilateral neglect of representational space. Cortex, 14, 129–133.

Bisiach, E., Perani. D., Vallar, G. & Berti. A. (1986). Unilateral neglect: Personal and extrapersonal. Neuropsychologia, 24, 759–767.

Bisiach, E. & Rusconi, M.L. (1990). Breakdown of perceptual awareness in unilateral neglect. Cortex, 26, 643–649.

Bisiach. E. & Vallar, G. (1988). Hemineglect in humans. In F. Bollar & J. Graffman (Eds). Handbook of neuropsychology. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Bradshaw, J.L., Nettleton, N.C., Pierson. J.M., Wilson. L.E., & Nathan. G. (1987). Coordinates of extracorporeal space. In M. Jeannerod (Ed.), Neurophysiological and neuropsychological aspects of spatial neglect. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Brain, W.R. (1941). Visual disorientation with special reference to lesions of the right hemisphere. Brain, 64, 244–272.

Caltagirone, C., Miceli, G., & Gainotti, G. (1977). Distinctive features of unilateral spatial agnosia in right and left brain damaged patients. European Neurology, 16, 121–126.

Calvanio, R., Petrone, P.N., & Levine, D.N. (1987). Left visual spatial neglect is both environment-centred and body-centred. Neurology, 37, 1179–1183.

Caplan, B. (1985). Stimulus effects in unilateral neglect? Cortex, 21. 69–80.

Caramazza, A. & Hillis, A.E. (1990). Spatial representation of words in the brain implied by studies of unilateral neglect. Nature, 346, 267–269.

Chamorro, A., Sacco, R.L., Ciecierski, K., Binder, J.R., Tatemichi, T.K., & Mohr, J.P. (1990). Visual hemineglect and hemihallucinations in a patient with a subcortical infarction. Neurology, 40, 1463–1464.

Colombo, A., De Renzi, E., & Faglioni, P. (1976). The occurrence of visual neglect in patients with unilateral cerebral disease. Cortex, 12, 221–231.

Coslett, H.B., Bower, D., Fitzpatrick, E., Haws, B., & Heilman, K. (1990). Directional hypokinesia and hemispatial attention in neglect. Brain, 113, 475-^86.

Costello, A. & Warrington, E.K. (1987). The dissociation of visual neglect and neglect dyslexia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 50, 1110–1116.

Critchley, M. (1953). The parietal lobes. New York: Hafner.

Cubelli, R., Nichelli, P., Boniot, V., De Tanti, A. & Inzaghi, M.G. (1991). Different patterns of dissociation in unilateral spatial neglect. Brain and Cognition, 15, 139–159.

Daffner, K.R., Ahern, G.L., Weintraub, S., & Mesulam, M.M. (1990). Dissociated neglect behaviour following sequential strokes in the right hemisphere. Annals of Neurology, 28, 97–101.

Delis, D., Robertson, L.C., & Balliet, R. (1985). The breakdown and rehabilitation of visuospatial dysfunction in brain injured patients. International Rehabilitation Medicine, 5, 132–138.

Denes, G., Semenza, C., Stoppa, E., & Lis, A. (1982). Unilateral spatial neglect and recovery from hemiplegia: A follow up study. Brain, 105, 543–552.

Denny-Brown, D. & Banker, B.Q. (1954). Amorphosynthesis from left parietal lesions. Archives of Neurology, 71, 302–313.

De Renzi, E. (1982). Disorders of space exploration and cognition. New York: John Wiley.

De Renzi, E., Faglioni, P., & Scotti, G. (1970). Hemispheric contribution to exploration of space through the visual and tactile modality. Cortex, 6, 191–203.

De Renzi, E., Gentillini, M., & Barbieri, C. (1989). Auditory neglect. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 52, 613–617.

Diller, L. & Gordon, W.A. (1981). Interventions for cognitive deficits in brain injured adults. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychiatry, 49, 822–834.

Diller, L. & Weinberg. J. (1977). Hemi-inattention in rehabilitation: The evolution of a rational remediation programme. In E.A. Weinstein & R.P. Friedland (Eds), Hemiinattention and hemispheric specialization. New York: Raven Press.

Doricci, F., Guariglia, C., Paolucci, S., & Pizzamiglio, L. (1991). Disappearance of leftward rapid eye movements during sleep in left visual hemi-inattention. Neuro-Report, 2, 285–288.

Driver, J. & Halligan, P.W. (1991). Can visual neglect operate in object centred co-ordinates? An affirmative single case study. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 8, 475–496.

Duke-Elder, W.S. (1949). Textbook of opthalmology: Vol.4. The neurology of vision, motor and optical anomalies. London: C.V. Mosby.

Ellis, A., Flude, B. & Young, A. (1987). “Neglect dyslexia” and the early visual processing of letters, words, and non-words. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 4, 439^164.

Ettlinger, G., Warrington, E.K., & Zangwill, O.L. (1957). A further study of visuo-spatial agnosia. Brain, 80, 335–361.

Faglioni, P., Scotti, G., & Spinnler, H. (1971). The performance of brain damaged patients in spatial localizations of visual and tactile stimuli. Brain, 94, 443–154.

Farah, M.J. (1989). The neuropsychology of mental image. In J.W. Brown (Ed.), Neuropsychology of visual perception. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Friedland, R. & Weinstein, E. (1971). Hemi-inattention and hemispheric specialization: Introduction and historical review. In E. Weinstein & R. Friedland (Eds), Hemi-inattention and hemispheric specialization. New York: Raven Press.

Fujii, T., Fukatsu, R., Kimura, I., Saso, S.I., & Kogure, K. (1991). Unilateral spatial neglect in visual and tactile modalities. Cortex, 27, 339–343.

Fullerton, K.J., McSherry, D., & Stout, R.W. (1986). Albert’s test: A neglected test of perceptual neglect. Lancet, 1, 430–432.

Gainotti, G. (1968). Les manifestations de negligence et d’inattention pour I’hemispace. Cortex, 4, 64–91.

Gainotti, G., Messerli, P., & Tissot, R. (1972). Qualitative analysis of unilateral spatial neglect in relation to laterality of cerebral lesions. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 35, 545–550.

Gainotti, G., Monteleone, D., & Silveri, M.C. (1986). Mechanisms of unilateral spatial neglect in relation to laterality of cerebral lesions. Brain, 109, 599–612.

Geschwind, N. (1965). Disconnection syndromes in animals and man. Brain, 88, 237–294, 585–644.

Girotti, G., Casazza, M., Musicco, M., & Avanzini, G. (1983). Occulomotor disorders in cortical lesions in man: The role of unilateral neglect. Neuropsychologia, 21, 543–55.

Gordon, W.A. & Diller, L. (1983). Stroke: Coping with a cognitive deficit. In T.E. Burish & L.A. Bradley (Eds), Coping with chronic disease. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Halligan, P.W., Cockburn, J., & Wilson, B. (1991a). The behavioural assessment of visual neglect. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 1, 5–32.

Halligan, P.W., Manning, L. & Marshall, J.C. (1991b). Hemispheric activation vs spatiomotor cuing in visual neglect: A single case study. Neuropsychologia, 29, 165–176.

Halligan, P.W. & Marshall, J.C. (1988). How long is a piece of string? A study of line bisection in a case of visual neglect. Cortex, 24, 321–328.

Halligan, P.W. & Marshall, J.C. (1991). Left neglect for near but not far space in man. Nature, 350, 498–500.

Halligan, P.W., Marshall, J.C., & Wade, D.T. (1989). Visuospatial neglect: Underlying factors and test sensitivity. Lancet, 2, 908–911.

Halligan, P.W., Marshall, J.C., & Wade, D.T. (1990). Do visual field deficits exacerbate visuospatial neglect. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 53, 487–491.

Halligan, P.W. & Robertson, I. (1992). The assessment of unilateral neglect. In J. Crawford, W. McKinlay, & D. Parker (Eds), A handbook of neuropsychological assessment. Hove: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Ltd.

Halsband, V., Gruhn, S., & Ettlinger, G. (1985). Unilateral spatial neglect and defective performance in one half of space. International Journal of Neuroscience, 28, 173–195.

Head, H. & Holmes, G. (1911). Sensory disturbances from cerebral lesions. Brain, 34, 102–254.

Hecaen, H. & Albert, N.L. (1978). Human neuropsychology. New York: John Wiley.

Hecaen, H. & Marie, P. (1974). Disorders of written language following right hemispheric lesions: Spatial dysgraphia. In S.J. Dimond & J.G. Beaumont (Eds), Hemisphere function in the human brain. London: Elek.

Heilman, K.M., Valenstein, I.E., & Watson, R.I. (1985a). The neglect syndrome. In J.A.M. Fredricks (Ed.), Handbook of clinical neurology, (vol. 45:1). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Heilman, K.M., Watson, R., & Valenstein, E. (1985b). Neglect and related disorders. In K.M. Heilman & E. Valenstein (Eds), Clinical neuropsychology, 2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hillis, A.E. & Caramazza, A. (1989). The graphemic buffer and attentional mechanisms. Brain and Language, 36, 208–235.

Holmes, G. (1918). Disturbances of visual orientation. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 2, 449–506.

Holmes, G. (1919). Disturbances of visual space perception. British Medical Journal, 2, 230–233.

Holmes, G. & Horrax, G. (1919). Disturbances of spatial orientation and visual attention, with loss of stereoscopic vision. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, 1, 385–407.

Horner, J., Massey, E., Woodruff, W., Chase, K., & Dawson, D. (1989). Task-dependent neglect: Computerised tomography size and locus correlations. Journal of Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 3, 7–13.

Humphrey, M.E. & Zangwill. O.L. (1952). Effects of right-sided occipito-parietal brain injuries in left handed man. Brain, 75, 312–320.

Ishiai, S., Furukawa, T., & Tsukagoshi, H. (1979). Eye fixation patterns in homonymous hemianopia and unilateral spatial neglect. Neuropsychologia, 25, 675–679.

Jackson, J.H. (1874). On the nature of the duality of the brain. Medical Press and Circular, 17, 19 (reprinted in Brain, 38, 80–103, 1915).

Jackson, J.H. (1876) Case of large cerebral tumour without ottic neuritis and with left hemiplegia and imperception. Royal Opthalmological Hospital Reports, 8, 434–444.

Jeannerod, M. (Ed.) (1987). Neurophysiological and neuropsychological aspects of spatial neglect. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Joanette, Y. & Brouchan, M. (1984). Visual allesthesia in manual pointing: Some evidence for a sensorimotor cerebral organization. Brain and Cognition, 3, 152–165.

Jones, E. (1910). Die Pathologie der Dyschirie. Journal fur Psychologic und Neurologic, 15, 145–183.

Karnath, H.O. & Hartje. W. (1987). Residual information processing in the neglected visual half-field. Journal of Neurology, 234, 180–184.

Karnath, H.O., Schenkel, P., & Fischer, B. (1991). Trunk orientation as the determining factor of the “contralateral” deficit in the neglect syndrome and as the physical anchor of the internal representation of body orientation in space. Brain, 114, 1997–2014.

Kartsounis, L.D. & Warrington, E.K. (1989). Unilateral visual neglect overcome by cues implicit in stimulus arrays. Journal of Neurology. Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 52, 1253 1259.

Kinsbourne, M. (1970). A model for the mechanism of unilateral neglect of space. Transactions of the American Neurological Association, 95, 143–146.

Kinsbourne, M. (1977). Hemi-inattention and hemispheric rivalry. In E.A. Weinstein & R.P. Friedland (Eds), Hemi-inattention and hemispheric specialization. New York: Raven Press.

Kinsbourne, M. & Warrington, E.K. (1962). A variety of reading disorders associated with right hemisphere lesions. Journal of Neurology. Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 25, 339–344.

Kinsella, G. & Ford, B. (1980). Acute recovery patterns in stroke patients. Medical Journal of Australia, 2, 663–666.

Ladavas, E. (1987). Is the hemispatial deficit produced by right parietal lobe damage associated with retinal or gravitational coordinates. Brain, 110, 167–180.

Laplane, D. (1990). La negligence mortice a-t-elle un rapport avec la negligence sensorielle unilaterale? Revue Neurologic (Paris), 146, 635 638.

Latto, R. (1984). Integration of clinical and experimental investigations of primate visual perception. In F. Reinsoso-Suarez & C. Ajmone-Marsan (Eds), Cortical integration. New York: Raven Press.

Levine, D.N. (1990). Unawareness of visual and sensorimotor defects: A hypothesis. Brain and Cognition, 13, 233–281.

Luria, A.R. (1972). The working brain. New York: Basic Books.

Marshall, J.C. & Halligan, P.W. (1988). Blindsight and insight in visuo-spatial neglect. Nature, 336, 766–767.

Marshall, J.C. & Halligan, P.W. (1989). Does the mid-sagittal plane pay any privileged role in “left” neglect? Cognitive Neuropsychology, 6, 403–422.

McFie, J., Piercy, M.F., & Zangwill, O.L. (1950). Visual spatial agnosia associated with lesion of the right cerebral hemisphere. Brain, 73, 167–190.

McFie, J. & Zangwill, O.L. (1960). Visual-constructive disabilities associated with lesions of the left cerebral hemisphere. Brain, 82, 243–259.

McGIynn, S.M. & Schacter, D.L. (1989). Unawareness of deficits in neuropsychological syndromes. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 11, 143–205.

Meador, K.J., Loring, D.W., Bowers, D., & Heilman, K.M. (1987). Remote memory and neglect syndrome. Neurology, 37, 522–526.

Mesulam, M.M. (1981). A cortical network for directed attention and unilateral neglect. Annals of Neurology, 10, 309–325.

Mesulam, M.M. (1985). Attention, confusional states and neglect. In M.M. Mesulam (Ed.). Principles of behavioural neurology. Philadephia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Ogden, J.A. (1985). Anterior-posterior interhemispheric differences in the loci of lesions producing visual hemi-neglect. Brain and Cognition, 4, 59–75.

Ogden, J.A. (1987). The neglected left hemisphere and its contribution to visuo-spatial neglect. In M. Jeannerod (Ed.), N europhysiological and neuropsychological aspects of spatial neglect. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Oxbury, J.M., Campbell. D.C., & Oxbury. S.M. (1974). Unilateral spatial neglect and impairment of spatial analysis and visual perception. Brain, 97, 551–564.

Patterson, A. & Zangwill, O.L. (1944). Disorders of visual space perception associated with lesions of the right cerebral hemisphere. Brain, 67, 331–358.

Patterson, A. & Zangwill. O.L. (1945). A case of topographical disorientation associated with a unilateral cerebral lesion. Brain, 68, 188–212.

Pick, A. (1898). Uber allegemeine gedachtnisschwache als unmittelbare folge cerebraler herderkrantung. In Beilrage zur Pathologic und Pathologische Anatomie des Central-ennerven-syslems mil bemerkingen zur normalen anutome desselben, pp. 168–185. Berlin: Karger.

Piercy, M.F., Hecaen, H., & Ajuriaguerra, J. (1960). Constructional apraxia associated with unilateral cerebral lesions. Brain, 83, 225–242.

Piggott, R. & Brickett, F. (1966). Visual neglect. American Journal of Nursing, 66, 101–105.

Pineas, H. (1931). Ein fall non raumlicher orientierungs-storung mit dsychirie. Zeitschrift fur de ges Neurologie und Psychiatric 133, 180–195.

Poppelreuter, W. (1917). Die strorungan der niederan und hoheren seheistungen durch nerletzung des okzipitalhirns. Die Psychischen Schadigungen durch Kopfschuss in Kreige (1914/1916), Leipzig: Voss.

Posner, M.I. & Rafal, R.D. (1987). Cognitive theories of attention and rehabilitation of attentional deficits. In R.J. Meier, L. Diller, & A.S. Benton (Eds). Neuropsychological rehabilitation. London: Churchill Livingstone.

Prigatano, G.P. & Schacter, D.L., (Eds). (1991). Awareness of deficit after brain injury. New York: Oxford University Press.

Riddoch, M.J. (Ed.) (1991). Neglect and the peripheral dyslexias. Hove: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Ltd.

Rizzollatti, G. & Camarda, R. (1987). Neural circuits for spatial attention and unilateral neglect. In M. Jeannerod (Ed.), Neurophysiological and neuropsychological aspects of spatial neglect. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Rizzollatti, G. & Gallese, V. (1988). Mechanisms and theories of spatial neglect. In F. Boiler & J. Grafman (Eds), Handbook of neuropsychology, Vol. 1. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Robertson, I. (1989). Anomalies in the laterality of omissions in unilateral left visual neglect: Implications for an attentional theory of neglect. Neuropsychologia, 27, 157–165.

Roth, M. (1949). Disorders of the body image caused by lesions of the right parietal lobe. Brain, 72, 89–111.

Rubens, A. (1985). Caloric stimulation and unilateral visual neglect. Neurology, 35, 1019–1024.

Scheller, H. & Seidmann, H. (1931). Zur fage der optischraumlichen agnosie (zugleich ein beitrag der dyslexie). Monalschrift fur Psychiatrie and Neurologic, 81, 97–188.

Schilder, P. (1935). The image and appearance of the human body. London: Kegan, Paul, Trench, and Tubner.

Seron, X., Coyette, F., & Bruyer, R. (1989). Ipsilateral influences on contralateral processing in neglect patients. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 6, 475–498.

Sieroff, E., Pollatsek, A., & Posner, M.I. (1988). Recognition of visual letter strings following injury to the posterior visual spatial attention system. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 5, 427–449.

Spinelli, D., Guariglia, C., Massironi, M., Pizzamilglio, L., & Zoccolotti, P. (1990). Contrast and low spatial frequency discrimination in hemi-neglect patients. Neuropsychologia, 28, 727–732.

Stone, S.P., Wilson, B., Wroot, A., Halligan, P.W., Lange, L.S., Marshall, J.C., & Greenwood, R.J. (1991). The assessment of visuo-spatial neglect after acute stroke. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 54, 345–350.

Tegner, R. & Levander, M. (1991). Through a looking glass: A new technique to demonstrate directional hypokinesia in unilateral neglect. Brain, 114, 1943–1951.

Vallar, G. & Perani, D. (1986). The anatomy of unilateral neglect after right hemisphere stroke lesions: A clinical CT scan correlation study in man. Neuropsychologia, 24, 609–622.

Vallar, G. & Perani, D. (1987). The anatomy of spatial neglect in humans. In M. Jeannerod (Ed.), Neurophysiological and neuropsychological aspects of spatial neglect. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Volpe, B.T., Le Doux, J.E., & Gazzangia, M.S. (1979). information processing in an “extinguished” visual field. Nature, 282, 722–724.

Warrington, E.K. (1991). Right neglect dyslexia: A single case study. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 8, 193–212.

Warrington, E.K. & Zangwill, O.L. (1957). A study of dyslexia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 20, 208–215.

Weinstein, E. & Friedland, R. (1977). Hemi-inattention and hemispheric specialization. New York: Raven Press.

Weintraub, S. & Mesulam, M. (1988). Visual hemispatial inattention: Stimulus parameters and exploratory strategies. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 51, 1481–1488.

Willanger, R., Danielson, V.T., & Ankerhus, J. (1981). Visual neglect in right sided apoplectic lesions. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 64, 327–336.

Young, A.W., de Haan, E.H., Newcombe, R., & Hay, D.C. (1990). Facial neglect. Neuropsychologia, 28, 391–415.

Zarit, S. & Kahn, R. (1974). Impairment and adaption in chronic disabilities: Spatial inattention. Journal of Nervous and Mental Diseases, 159, 63–72.

Zingerle, H. (1913). Ueber storrungen der wahrnemung des eigenen koerpers bei organischen gehirnerkrankungen. Monatschrift für Psychiatrie und Neurologic, 34, 13–36.