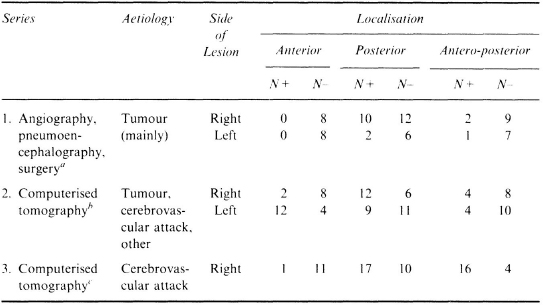

Table 2.1

Localisation of Lesion in Patients with and without Contralesional Visual Hemineglect (N+, N−)

aBattersby et al. (1956); bOgden (1985); cVallar and Perani (1986; 1987).

The Anatomical Basis of Spatial Hemineglect in Humans

Istituto di Clinica Neurologica, Università di Milano, Milano, and Clinica S. Lucia, Roma, Italy

Introduction

Unilateral spatial neglect may be associated with both left- and right-sided lesions, but is much more frequent and severe after lesion of the right hemisphere. At the clinical level, neglect may be operationally defined as a behavioural disorder whereby a patient fails to explore the half-space contralateral to the cerebral lesion and this deficit cannot be attributed to the impairment of elementary sensori-motor processes. In line with this working definition, neglect is clinically assessed by spatial exploratory tasks, such as pattern crossing (e.g. circles, lines), line bisection, copying, drawing and reading tasks. Most tests involve visual exploration of extrapersonal space, but tactile versions, in which the patient is blindfolded, have been devised. In this type of task, the patient is free to move his or her head and makes use of the non-paretic hand. Under these conditions, the defective exploration of the contralateral half-space cannot be explained in terms of elementary sensori-motor disorders. Consistent with this view, spatial hemineglect is double-dissociated from hemiplegia, hemianopia and hemianaesthesia, even though such disorders are frequently found in patients with neglect (see Bisiach & Vallar, 1988). The precise nature of the processing deficit underlying hemianopia and hemianaesthesia in neglect patients is not clear, however, and recent observations argue cogently for an important role of the impairment of non-peripheral processing components, suggesting that these apparently primary sensory deficits may be themselves a manifestation of neglect (Kooistra & Heilman, 1989; Vallar et al., 1990, 1991a; Vallar, Sandroni, Rusconi, & Barbieri, 1991b). Despite these recent suggestions, the distinction between sensory and neglect components in the genesis of hemianopia and hemianaesthesia cannot be easily drawn by a clinical examination, and the diagnosis of hemineglect is mainly based upon the observation of a defective exploration of the contralateral half-space. Accordingly, in virtually all studies investigating the anatomical correlates of neglect, the presence/absence of the disorder has been assessed by exploratory tasks of the sort mentioned above.

The present chapter comprises four sections and a resume. First, I review the traditional anatomo-clinical correlation studies, based upon postmortem pathological evidence or upon radiological techniques [brain scan, computerised tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)]. All such methods may show structural damage of the brain involving neuronal loss and provide information concerning the site, size and aetiology of the cerebral lesion. I then consider more recent observations, based on imaging methods such as positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), which may reveal the dysfunction of specific regions of the brain in the absence of structural damage. Next, I discuss the anatomical correlates of a number of discrete components of spatial hemineglect. I follow this up with a discussion of the neural correlates of recovery from hemineglect.

In each section, the discussion will be confined to the neural correlates of hemineglect, operationally defined as a defective exploration of the contralateral half-space, although a number of associated and more or less related disorders (e.g. extinction, allaesthesia, motor neglect, motor impersistence, anosognosia, anosodiaphoria) are frequently listed under the rubric of the “neglect syndrome” (Heilman, Watson, & Valenstein, 1985a). These disorders are frequently associated with neglect, but instances of double dissociations have been reported, such as hemineglect vs anosognosia and hemineglect vs extinction (see Bisiach & Vallar, 1988). The existence of dissociations such as those mentioned above appears to indicate that the symptom-complex “neglect syndrome” is likely to reflect the anatomical contiguity of cerebral regions involved in the processing of different aspects of personal and extrapersonal space. Seen in this perspective, a symptom-complex such as that of Heilman et al. (1985a) may be regarded as an instance of anatomical, rather than anatomo-functional, syndrome (see discussion in Vallar, 1991a). According to the former view, the neural mechanisms involved in different aspects of spatial processing and awareness may be conceived in terms of complex neural circuits located in adjacent cerebral regions. This would explain both the frequent association of symptoms and the occurrence of dissociated cases. That this is likely to be the case is suggested by the observation in the monkey that small experimental lesions located in adjacent areas may be associated with different patterns of neglect. For instance, the surgical ablation of the postarcuate frontal cortex (area 6) and of the frontal eye fields (area 8) produce neglect for the peripersonal and “far” space, respectively (Rizzolatti, Matelli, & Pavesi, 1983). The two areas are adjacent and even precise experimental lesions performed under microscope control aimed at ablating one area may marginally involve the other (see, for instance, monkey PI of Rizzolatti et al., 1983). The site and size of naturally occurring lesions, by contrast, are not related to the functional role of the different cerebral areas, but other factors are relevant, such as the vascular territory to which any given cerebral area belongs (see Damasio, 1983). It is then not surprising that in humans, in whom the lesions are produced by natural diseases such as cerebrovascular attacks, tumours and the like, the putative components of the neglect syndrome frequently co-occur, and the observed behavioural dissociations frequently do not have a clear-cut anatomical counterpart (Bisiach, Perani, Vallar, & Berti, 1986a; Bisiach et al., 1986b; Halligan & Marshall, 1991).

Anatomical Correlates of Spatial Hemineglect

Since its discovery as a neurological deficit, spatial hemineglect has been regarded as a symptom with a remarkable localising value, which indicates a lesion of the parietal lobe (Adams & Victor, 1985; Brain, 1941; Critchley, 1953; Jewesbury, 1969; McFie, Piercy, & Zangwill, 1950). However, in the last 20 years, the availability of non-invasive radiological techniques has mitigated this conclusion, providing clear evidence that both lesions located outside the parietal lobe and purely subcortical lesions sparing the cortex may produce spatial hemineglect.

Cortico-Subcortical Lesions

After the early reports of Zingerle (1913) and Silberpfennig (1941), ample evidence has been accumulated to the effect that right frontal lesions may produce left hemineglect (Castaigne, Laplane, & Degos, 1972; Heilman & Valenstein, 1972a); Van der Linden, Seron, Gillet, & Bredart, 1980). Patients with right neglect associated with left frontal lesions have also been reported (Damasio, Damasio, & Chang Chui, 1980). Systematic anatomo-clinical correlation studies performed on series of patients have, however, shown that the more frequent cortical correlate in humans is a retro-rolandic lesion involving the temporo-parieto-occipital junction. Table 2.1, which draws upon three group studies performed in large series of brain-damaged patients collected after the Second World War, summarises the lesion sites in patients with and without visual hemineglect. The three studies differ in a number of important respects, such as aetiology and radiological assessment of the cerebral lesion, time interval between onset of the disease and neuropsychological investigation, behavioural tasks used to detect neglect (see a discussion of the potential biasing effects of these factors in Vallar & Perani, 1987). They concur nevertheless to indicate that left spatial hemineglect is much more frequently associated with right posterior lesions than with right frontal damage. The series of Vallar and Perani (1986) included stroke patients examined within 30 days after stroke onset. In a series of 24 chronic neglect patients assessed 2 or more (median 5) months after stroke onset, Cappa et al. (1991) have confirmed the main role of posterior damage. Thirteen patients (54%) had antero-posterior lesions, 6 (25%) posterior or postero-mesial lesions, while no patient had anterior damage; 5 patients had deep lesions.

Table 2.1

Localisation of Lesion in Patients with and without Contralesional Visual Hemineglect (N+, N−)

aBattersby et al. (1956); bOgden (1985); cVallar and Perani (1986; 1987).

The studies of Battersby, Bender, Pollack and Kahn (1956) and Ogden (1985) also included left brain-damaged patients. Battersby et al. (1956) found that right hemineglect, which is less frequent than left hemineglect, also tends to be associated with retro-rolandic lesions. Ogden (1985) reported that right hemineglect produced by left-sided lesions is as frequent, albeit less severe, as left hemineglect produced by right-sided lesions. Secondly, she found an anatomical dissociation, since right hemineglect was associated with anterior lesions. This latter find has not been replicated to date, even though individual cases of right hemineglect produced by left-sided frontal lesions have been reported (e.g. Damasio et al 1980). One possible explanation for this is that, at variance with Ogden’s (1985) findings, in most studies right hemineglect associated with left-sided lesions has been found not to be a frequent phenomenon, preventing therefore meaningful anatomo-clinical correlations. For instance, Hecaen (1972. p. 212), in a large series of patients with unilateral cerebral lesions, assessed surgically or by post-mortem examination, found contralateral hemineglect in 56 out of 179 patients with right-sided lesions, and in 1 out of 286 patients with left-sided lesions. Similarly, in the study of Bisiach, Cornacchia, Sterzi and Vallar (1984), who used a visual exploratory task, 15 out of 56 right brain-damaged patients showed left hemineglect, which was absent in the 51 left brain-damaged patients. Vallar et al. (1991c) found visual or tactile contralateral neglect in 23 out of 66 (35%) right brain-damaged patients and in 4 out of 44 (9%) left brain-damaged patients. Over 80% of their patients had suffered a cerebrovascular attack and were investigated within 30 days after stoke onset. The four left brain-damaged patients had a parietal tumour (case 7) and frontal, temporo-insular and subcortical (basal ganglia and white matter) ischaemic lesions (cases 18–20). Two out of four patients, therefore, had anterior lesions (see Ogden. 1985), but the series is too small to warrant definite conclusions.

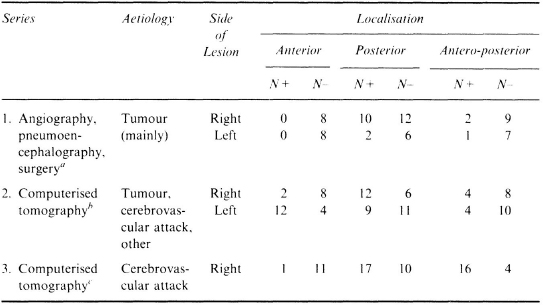

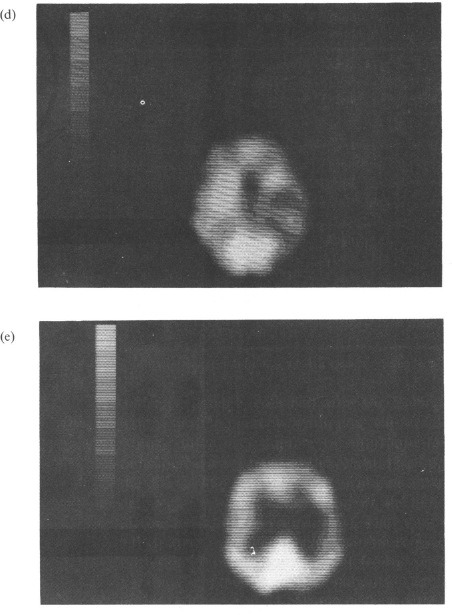

In a number of studies, the precise site of the right retro-rolandic lesion associated with left spatial hemineglect has been investigated. The available evidence concurs to suggest a pivotal role of lesions involving the infero-postcrior regions of the right parietal lobe (Bisiach, Capitani, Luzzatti, & Perani, 1981; Hecaen, Penfield, Bertrand. & Malmo, 1956: Heilman & Valenstein. 1972b; Vallar & Perani, 1986). Figure 2.1 shows the composite contour maps of the posterior right-sided lesions of patients with and without left visual hemineglect. It is apparent that the inferior parietal lobule is damaged in neglect patients, and comparatively spared in unaffected cases. In this latter group, the lesions involve the superior parietal lobule or are located more posteriorly in the occipital regions.

Fig. 2.1. Composite contour maps of the posterior deep-and-superficial right-sided lesions of (a) 8 patients with severe left hemineglect, (b) 6 patients with mild-to-moderate neglect and (c) 10 patients without neglect. The contours drawn on the standard lateral diagram of the brain represent the degree of overlap of the lesions; the outer line indicates the area affected by one lesion only, the next by two and so forth. Reprinted with permission from Vallar and Perani (1986).

The dissociation between superior and inferior parietal lobe damage is in line with data concerning the anatomical correlates of reaching disorders. In Ratcliff and Davies-Jones’ series (1972), non-hemianopic left and right brain-damaged patients with gross impairment of visual localisation in the contralateral half-field had lesions clustering in the superior parietal region. Similarly, the patient of Levine, Kaufman and Mohr (1978), who suffered from a tumour involving the right superior parietal lobule, had misreaching for visual objects without extinction or neglect. A third study relevant here was made by Posner, Walker, Friedrich and Rafal (1984), who suggested a correlation between CT-assessed superior parietal lesions and deficits in the orientation of attention towards targets located in contralateral half-space. The 12 patients of Posner et al. (1984), however, had no or minimal-to-mild signs of contralateral visual hemineglect, as assessed by exploratory tasks, while visual extinction to double simultaneous stimulation was a constant feature. Finally, Kertesz and Dobrowolsky (1981) found an association of left neglect with lesions involving the right fronto-temporo-parietal junction (which includes the inferior parietal lobule), but not with either purely frontal or superior parietal lesions.

These studies indicate that lesions confined to or clustering in the superior parietal regions tend to be associated with disorders such as visual misreaching or extinction, but not with hemineglect. They therefore corroborate the conclusion illustrated in Fig. 2.1 that the crucial cortical correlate of hemineglect is a lesion involving the inferior parietal region. Finally, the data mentioned above provide some indication that the anatomical correlates of visual extinction and hemineglect may be different, suggesting a dissociation between the two disorders (see relevant data in Vallar & Perani, 1986; cf. Heilman et al., 1985a).

The observation that lesions confined to the occipital regions are not associated with hemineglect ties in with the well-known finding that hemianopia and hemineglect are double-dissociated deficits (see, e.g. Bisiach et al., 1986a; Halligan, Marshall & Wade, 1990; Hecaen, 1962; Vallar & Perani, 1986). These anatomical data therefore corroborate the notion that hemineglect cannot be explained in terms of defective sensory processing (see Bisiach & Vallar, 1988). In line with these conclusions, Koehler, Endtz, Te Velde and Hekster (1986) have found that patients anosognosic for homonymous hemianopia have CT-assessed lesions clustering in the inferior-posterior parietal regions, which are spared however in patients aware of their visual field deficit. In these latter patients, by contrast, the lesions superimpose in the occipital lobe. These data suggest a role for the inferior parietal regions in monitoring the function of the visual areas and argue for a close relation between anosognosia for hemianopia and spatial hemineglect.

Vallar et al. (1991b) have shown preserved visual evoked potentials to contralateral stimulation in two right brain-damaged patients with neglect and anosognosia for left hemianopia. The patients were entirely unaware of the left visual half-field stimulation which produced normal evoked potentials. The lesions largely spared the primary sensory occipital areas: one patient had a small ischaemic lesion in the right occipital paraventricular white matter; the second patient an extensive fronto-temporo-parietal infarction. Visual evoked potentials may be used for distinguishing “primarily sensory” hemianopia from visual hemi-inattention. Denial of contralateral hemianopia in neglect patients with CT- or MRI-assessed lesions sparing the primary sensory occipital cortex raises the possibility that the visual field deficit is not sensory in nature.

A consistent association between purely subcortical lesions and hemineglect was discovered only after the introduction of CT scan in clinical practice, even though instances of neglect phenomena in patients with subcortical lesions may be found in the classic literature (Pick, 1898) and in more recent clinico-pathological studies (Oxbury, Campbell, & Oxbury, 1974). A more extensive discussion of the role of subcortical lesions in producing cognitive deficits, such as spatial hemineglect and dysphasia, may be found in Cappa and Vallar (1992).

Thalamus. Since the late 1970s, a number of individual case reports of CT-assessed right thalamic lesions associated with left hemineglect have been published (Cambier, Elghozi, & Strube, 1980: 3 cases; Schott, Laurent, Mauguiere, & Chazot, 1981: 1 case; Watson & Heilman, 1979: 3 cases; Watson, Valenstein, & Heilman, 1981: 1 case). In the patients of Watson and Heilman (1979, case 3) and Cambier et al. (1980, case 1), the thalamic lesion was confirmed by post-mortem examination. The role of thalamic damage in producing hemineglect is also suggested by the observation of spatial and motor neglect after stereotactic lesions performed for the relief of Parkinson’s disease (Hassler, 1979; Perani, Nardocci, & Broggi, 1982; Velasco, Velasco, Ogarrio, & Olvera, 1986).

In a number of patients, an intra-thalamic localisation of the lesion has been attempted. In case 1 of Cambier et al. (1980), the pathological examination showed a lesion of the pulvinar, and of the ventro-postero-lateral and dorso-medial nuclei. In the patient of Watson et al. (1981), the lesion was reported to involve the postero-ventral and the medial thalamic nuclei, and possibly the antero-inferior pulvinar. The patient of Schott et al. (1981) suffered a haematoma presumably confined to the pulvinar. Graff-Radford et al. (1985) investigated the patterns of neuropsychological deficits associated with ischaemic, well-demarcated lesions of different portions of the thalamus. They found left hemineglect in patients with postero-lateral (one case, with an associated posterior cerebral artery infarction) and medial (one case) right thalamic lesions. The negative cases of Graff-Radford et al. (1985) comprised four postero-lateral, two antero-lateral and two lateral thalamic/posterior limb of internal capsule infarctions. Hirose et al. (1985) reported left hemineglect in four patients with a right posterior thalamic haemorrhage. Case 3 of Cappa, Sterzi, Vallar and Bisiach (1987) had an haemorrhagic lesion involving the right posterior thalamus, and the genu and posterior limb of the right internal capsule. In the clinical study of Bogousslavsky, Regli and Uske (1988b), left hemineglect was associated with ischaemic lesions of the paramedian part of the thalamus (intralaminar and dorsomedial nuclei) and tuberothalamic infarction (ventral-anterior, ventral-lateral, and most of the dorso-medial nuclei).

To summarise, the data from published individual case studies appear to indicate a major role of posterior and medial thalamic damage, as compared with lesions located more anteriorly.

Basal Ganglia. The individual case reports of hemineglect associated with basal ganglia damage are less frequent. Hier, Davis, Richardson and Mohr (1977) briefly mention a “nondominant hemisphere syndrome”, including neglect in seven out of nine alert patients with a CT-assessed right putaminal haemorrhage. Damasio and co-workers’ (1980) patient had a CT-assessed lesion involving the right putamen, the body of the caudate nucleus and portions of the internal capsule. In the patient of Healton, Navarro, Bressman and Brust (1982), the post-mortem examination revealed an infarction of the head of the right caudate nucleus, putamen, internal and external capsule. Ferro, Kertesz and Black (1987) found evidence of visual hemineglect in 10 out of 15 patients with CT- or MRI-assessed subcortical infarcts, involving the basal ganglia and/or the white matter and the internal capsule. The deficit was severe in only three patients (cases 2, 8 and 9), two of whom (cases 2 and 8) had a substantial involvement of the posterior limb of the internal capsule.

White Matter. Visual hemineglect has been repeatedly found to be associated with CT-assessed lesions involving the posterior limb of the internal capsule, in the vascular territory of the anterior choroidal artery (Bogousslavsky et al., 1988a: 2 cases; Cambier et al., 1983: 3 cases; Ferro & Kertesz, 1984: 1 case; Masson et al., 1983: 3 cases; Vallar et al., 1990: case 2). Case 3 of Stein and Volpe (1983) had a subcortical infarction in the frontal lobe.

These reports of individual patients with subcortical lesions and visual hemineglect suggest a main role of thalamic and basal ganglia damage, followed by white matter lesions. This conclusion has been supported by the group study of Vallar and Perani (1986), who investigated the association of visual hemineglect in a continuous series of 51 patients with CT-assessed vascular subcortical lesions, who were examined within 30 days after stroke onset. In this study, 50% (2/4) of the patients with thalamic lesions, 28% (7/25) of the patients with basal ganglia lesions and 5% (1/19) of the patients with white matter/internal capsule lesions showed neglect. The three patients with extensive lesions involving both the thalamus and the basal ganglia had visual hemineglect. By and large, in line with these findings, Fromm, Holland, Swindell and Reinmuth (1985) found an association between thalamic (1/3 patients) and basal ganglia (3/4 patients) lesions and visual hemineglect. By contrast, two patients with a lacunar stroke in the internal capsule showed no signs of neglect.

These conclusions concerning the different effects of various subcortical lesion sites should consider, however, that the size of the lesion may also play an important role. For instance, in most of Vallar and Perani’s (1986) patients with thalamic or basal ganglia lesions, who showed the more consistent association with neglect, the damage also involved the white matter and/or portions of the internal capsule. By contrast, the grey nuclei were spared in patients with lesions confined to the white matter and the internal capsule, who rarely showed signs of hemineglect. The more frequent association of thalamic and basal ganglia damage with neglect might be therefore attributed, at least in part, to the greater lesion volume, since in these patients both the grey and the white matter are involved (see related data, showing a relationship between the size of the subcortical lesion and the occurrence of neuropsychological deficits in Perani et al., 1987).

An indication that the volume of the lesion is not the only factor to be taken into consideration comes from the observation, based on detailed anatomo-clinical correlations in individual patients, that some lesion sites appear to be specifically related to visual hemineglect. This is the case of posterior thalamic and white matter lesions involving the posterior limb of the internal capsule. This pattern of association, together with the well-known finding that the main cortical correlate of human neglect is postero-inferior parietal damage, argues for an important role of a neural circuit comprising as main components the infero-posterior parietal cortex and the thalamic nuclei connected with this cortical area. The pulvinar is likely to be an important part of such a circuit: Located in the posterior part of the thalamus, it receives afferents from structures that in turn receive visual input (among others, the occipital lobe and the superior colliculus). The main output of the pulvinar is conveyed, via the posterior limb of the internal capsule, to the posterior parietal lobe (see more details and references in Hyvarinen, 1982). A similar line of reasoning may be applied to the association between dorso-medial thalamic lesions and neglect, since the nucleus medialis dorsalis provides the major thalamic input to the frontal eye fields (area 8) (see Barbas & Mesulam, 1981; Mesulam, Van Hoesen, Pandya, & Geschwind, 1977; Mesulam, 1985) and lesions of this cortical region produce a severe extrapersonal neglect in the monkey (see data and references in Rizzolatti et al., 1983).

Functional Anatomy of Hemineglect

The anatomo-clinical correlation studies reviewed in the previous section are compatible with the view that hemineglect is produced by the disruption of complex neural circuits. This conclusion is also in line with studies in animals, in which neurological deficits broadly comparable to human hemineglect are produced by a range of experimental focal lesions (see reviews in Rizzolatti & Camarda, 1987; Rizzolatti & Gallese, 1988). Arguments for a network approach to the neural correlates of complex behaviour have also been advanced in different theoretical perspectives in cognitive neuroscience, such as neurobiological research at the cellular and synaptic levels (see Changeux & Dehaene, 1989; Getting 1989) and “distributed processing”, “connectionist” or “neural network” modelling of cognitive function (see Morris, 1989; Rumelhart & McClelland; 1986).

The correlation studies discussed in the previous section, in which a given clinical pattern is correlated with a specific lesion site, though compatible with a network approach to cognitive function, do not provide direct and circumstantial support, however. They simply suggest that a number of specific cerebral regions may be more or less important for the operation of a given function. More direct evidence comes from functional imaging techniques, such as positron emission tomography (PET) and single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), that assess functional activity of the brain in terms of regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) and metabolism.

In the last 10 years, much evidence has been provided to the effect that a focal structural lesion, such as a stroke or a tumour, may produce a functional derangement in far removed areas, which appear entirely normal on standard CT or MRI assessment (see illustrative examples in Celesia et al., 1984; Kuhl, et al., 1980). This derangement, a revisited and up-to-date version of the classical concept of “diaschisis” (von Monakow, 1914), may be revealed as a pathological reduction of rCBF and metabolism. In these affected areas, the neural cells, though viable, are dysfunctional. The remote effects of diaschisis are produced by the interruption of afferent fibre pathways. So, the lesion of the cerebral region “A”, which projects to “B”, may produce hypoactivity in “B” (see a review in Feeney & Baron, 1986). These remote effects involve primarily regions ipsilateral to the lesion, which receive major projections from the damaged area (Girault et al., 1985; London et al., 1984). However, a reduction in metabolism in the contralateral hemisphere also occurs (see Dobkin et al., 1989; Ginsberg, Reivich, Giandomenico, & Greenberg, 1977; Kiyosawa et al., 1989; for a review, see Andrews, 1991). This mechanism, whereby a lesion affects the function of remote but connected areas, is compatible with the view that cognitive or more basic functions are implemented in neural circuits, comprising a number of interconnected components. This approach has been widely applied to the study of aphasia, showing that language disorders are associated with the dysfunction of a number of interconnected areas, in addition to the structural focal lesion (for a review, see Metter, 1987; 1992).

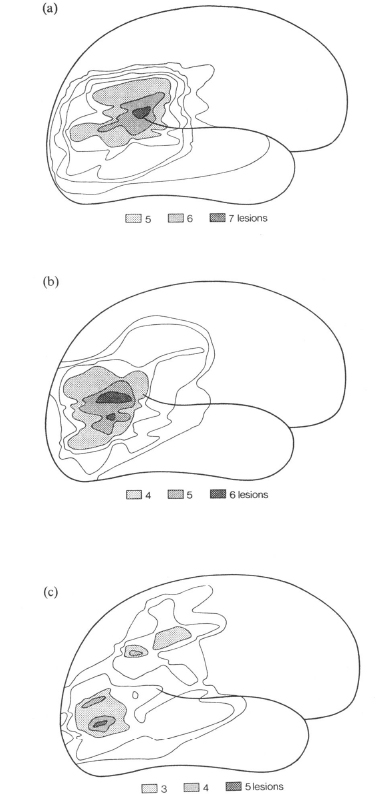

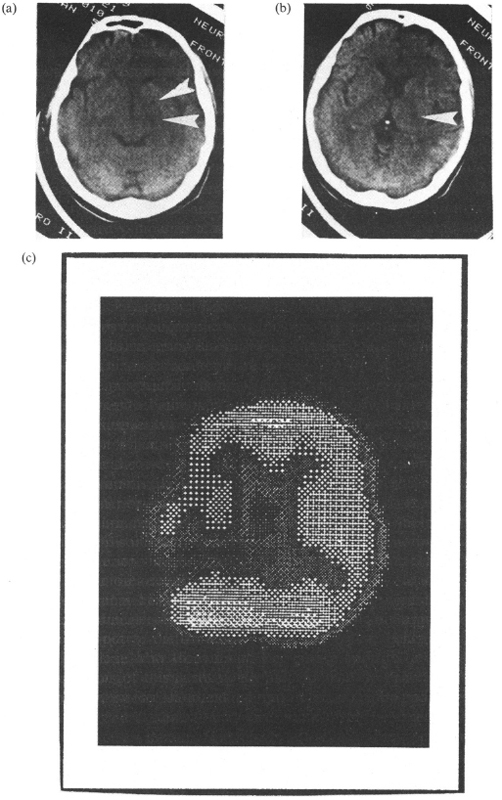

As for spatial hemineglect, a few studies have attempted to investigate the relationships between diaschisis and the behavioural deficit. In a series of patients suffering from right subcortical stroke, Perani et al. (1987) found that the neglect group had a significantly greater cortical hypoperfusion, as compared with the patients without neglect. In a follow-up study, Vallar et al. (1988) found that behavioural recovery from neglect paralleled reduction of cortical hypoperfusion. Figure 2.2 shows one such case, a patient with a right thalamic haematoma and reduction of rCBF in the right fronto-temporo-parietal areas that improved over time.

Fig. 2.2. A patient with contralateral hemineglect. (a) CT scan showing a right thalamic haemathoma. (b, c) Initial SPECT (Orbitomeatal line +3.9 and +6.3) showing a large area of hypoperfusion in the fronto-temporo-parietal areas of the right hemisphere, (d, e) Follow-up SPECT (Orbitomeatal line +3.9 and +6.3) showing reduction of cortical hypoperfusion. Reprinted with permission from Vallar et al. (1988).

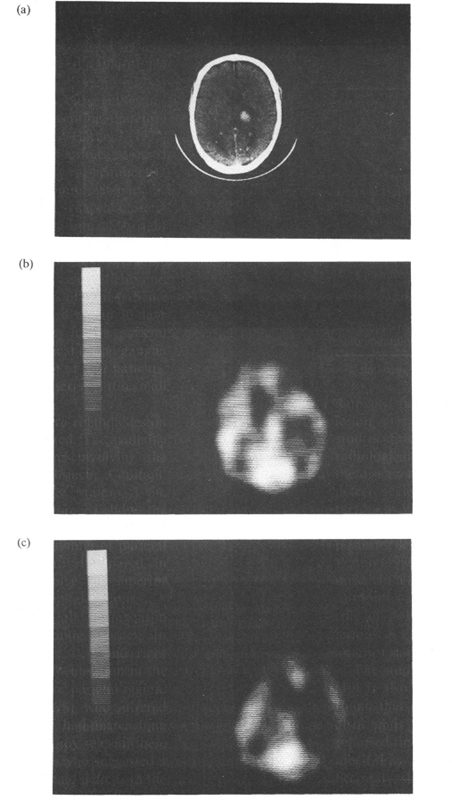

These results have subsequently been replicated by Bogousslavsky et al. (1988a), who reported two patients with left hemineglect and CT-assessed infarction in the vascular territory of the right anterior choroidal artery. A SPECT study revealed marked hypoperfusion in the overlying right parietal cortex and, to a lesser extent, in the right frontal cortex. In case 1 of Bogousslavsky et al. (1988a), a post-mortem examination confirmed the lesion in the territory of the anterior choroidal artery, showing that the cerebral cortex was entirely spared. A similar pattern, shown in Fig. 2.3, has recently been reported by Vallar et al. (1990).

Fig. 2.3. A patient with contralateral hemineglect. (a, b) CT scan showing a right-sided ischaemic lesion in the vascular territory of the anterior choroidal artery, (c) SPECT showing hypoperfusion in the posterior parietal regions of the right hemisphere (the image is inverted, according to neuroradiological conventions). Reprinted with permission from Vallar et al. (1990).

These results show that in the case of subcortical damage, the presence of spatial hemineglect is related to the cortical functional derangement. They also provide an explanation of the well-known clinical finding that purely subcortical lesions are not systematically associated with neglect (see the series of Vallar & Perani, 1987): In such negative cases, the functional derangement of the cortico-subcortical circuits is comparatively less severe, as shown by the minor reduction of rCBF (see Perani et al., 1987). Finally, these data may account for the main role of thalamic lesions in producing neuropsychological deficits: As cortical diaschisis is caused by the interrup tion of afferent input, damage of the main source of cortical projections is likely to be frequently associated with cognitive disorders (see also Franck, Salmon, Sadzot, & Van der Linden, 1986; Pappata et al., 1990). Seen from this perspective, the size effect found by Perani et al. (1987), namely that lesions producing a major cortical hypoperfusion and neglect are larger than lesions not associated with this deficit, reflects the greater involvement of the thalamo-cortical projection, even though the possible disruption of extrathalamic cortical afferents (see Foote & Morrison, 1987) may be a relevant factor. The damage to the thalamocortical projection may also produce cortical diaschisis in the case of structural lesions sparing the thalamus, but involving the internal capsule and the subcortical white matter (e.g. Rousseaux et al., 1986; Vallar et al., 1990). In line with this view, in Ferro and co-workers’ (1987) series of right brain-damaged patients with basal ganglia infarction, the lesion also involved the internal capsule when neglect was severe.

The observation that in patients with subcortical lesions neglect is directly related to cortical dysfunction is, at least prima facie, in accord with the traditional view (e.g. Nielsen, 1946) which assigns an exclusive role in cognition to the cerebral cortex (and to the fibre tracts connecting cortical areas). According to this hypothesis, a subcortical lesion produces cognitive deficits only by non-specific effects, such as cortical hypoactivation.

Two arguments, however, militate against this conclusion (see a discussion of this issue in Cappa & Vallar, 1992). The anatomo-clinical observations reviewed in the previous section of this chapter indicate that, while a number of subcortical lesion sites may produce spatial hemineglect, some specific locations appear to show a closer association with the disorder. This is the case of posterior and medial thalamic lesions and of damage to the posterior limb of the internal capsule. The conclusion that some subcortical areas may play a specific role in cognition is supported by the observations that neuropsychological disorders different from hemi-neglect are associated with specific intrathalamic lesion sites. Anterior and ventral-lateral left-sided thalamic vascular lesions are frequently associated with aphasia, but this is not the case for posterior thalamic lesions, even though exceptions to this pattern are on record (see a review and data in Cappa, Papagno, Vallar, & Vignolo, 1986). Chronic amnesia is associated with small bilateral medial thalamic infarctions that are located anteriorly and disrupt specific connections, such as the mammillo-thalamic tract (see a review and anatomo-clinical case studies in Graff-Radford, Tranel, Van Hoesen, & Brandt, 1990). These observations concur to indicate that different portions of the thalamus are involved in specific cognitive activities. This conclusion differs from neural models, which, as traditionally maintained (e.g. Nielsen, 1946), argue that the neurological correlate of spatial directed attention is a cortical network, while subcortical structures have only a non-specific activation role (Mesulam, 1981; see also Mesulam, 1990, who assigns more specific roles to some subcortical structures; for instance, the striatum would integrate neural computations taking place in the frontal eye fields with those in the posterior parietal region).

A second line of evidence suggesting that the neural mechanisms involved in spatial representation comprise specific cortico-subcortical circuits comes from studies performed by Deuel in the monkey (Deuel & Collins, 1983, 1984; Deuel, 1987). These experiments represent the counterpart of the human studies mentioned above. Deuel made cortical (frontal or parietal) lesions producing neglect,1 mapped regional metabolic brain activity (2-deoxyglucose method) by autoradiography, and found hypometabolism in a number of ipsilateral subcortical regions (basal ganglia, thalamus, tectum) far removed from the experimental lesion. Parietal lesions also produced a mild hypometabolism in the ipsilateral visual and somaesthetic cortex. Recovery was associated with reduction of hypometabolism in the affected subcortical regions.

To summarise, the few available functional studies in human patients with hemineglect suggest that the neural mechanisms of spatial representation and awareness may be conceived in terms of neural cortico-subcortical circuits. This conclusion is in line with the study by Metter, Riege, Kuhl and Phelps (1984), who investigated the metabolic relationships among a number of different brain regions in normal adult humans. By measuring regional cerebral metabolism in a resting state, Metter et al. identified two sets of cerebral regions which show correlated metabolic activities: an inferior system, involving the inferior frontal, Broca’s and posterior temporal regions, possibly participating in language-related functions; a superior system comprising the superior and middle frontal gyri, the inferior parietal lobule and the occipital cortex, possibly involved in visuo-spatial processing. The superior frontal region of Metter et al. (1984) includes the frontal eye fields. In the monkey, damage to this region produces a deficit broadly similar to human extrapersonal neglect (Kennard, 1939; Latto & Cowey, 1971a, 1971b; Rizzolatti et al., 1983) and neglect after frontal damage has been repeatedly observed in humans.

A contribution of the frontal regions to the visual exploration of extrapersonal space is also suggested by the intracarotid amobarbital study of Spiers et al. (1990). In a series of 48 patients with epilepsy, they confirmed the hemispheric asymmetry of hemineglect, which was produced only by right-sided injections, and found an association between neglect and EEG slowing in the right frontal areas.

While both human and animal data concur to indicate that the neural mechanisms of spatial representation and awareness should be conceived in terms of cortico-subcortical neural circuits, a difference between man and monkey should be mentioned. In humans, the available CT and functional data suggest that structures such as the inferior parietal lobule may have a particularly relevant role to play. In the monkey, the typical correlate of neglect is a frontal lesion, and parietal neglect is considered somewhat less profound (Hyvarinen, 1982; Lynch, 1980; Lynch & McLaren, 1989), even though neglect deficits after parietal damage have been reported (Denny-Brown & Chambers, 1958; Rizzolatti & Camarda, 1987; Rizzolatti, Gentilucci, & Matelli, 1985; Rizzolatti et al., 1983; for a discussion of the possible “discontinuity” between the cerebral organisation of spatial representation in man and monkey, see Ettlinger, 1984). This man vs monkey difference appears to indicate that in humans the neural network involved in spatial representation is likely to comprise both frontal and parietal systems (such as the frontal eye fields and the inferior parietal lobule), but the parietal component has had a major development. This main role of the parietal regions in spatial representation might possibly be related to the well-known involvement of the human frontal cortex in control and executive functions.

The Fractionation of Spatial Hemineglect: Neural Correlates

In the previous sections, spatial hemineglect has been treated as a unitary disorder, basically for the pragmatic reason that the vast majority of the anatomoclinical correlation studies reviewed have not attempted to distinguish putatively different component deficits. In recent years, however, dissociations between different aspects of neglect have been reported. In this section, the available empirical evidence concerning the neural correlates of such dissociation will be reviewed (see also Chapter 4, this volume).

Premotor vs Perceptual Components of Neglect

A number of anatomo-physiological models of directed attention in extrapersonal space distinguish between “pre-motor” and “perceptual” neural mechanisms. In Mesulam’s (1981; 1990) model, the perceptual component provides an internal map of extrapersonal space, while the premotor component is involved in the programming and execution of movements (e.g. fixation, reaching) for exploration of such a space. The posterior parietal and the dorso-lateral pre-motor cortices are the major neural correlates of these two systems. Similarly, Heilman et al. (1985a) distinguish between two cortico-subcortical loops: (1) the temporo-parieto-occipital junction, the posterior cingulate gyrus and some thalamic nuclei (ventralis postero-lateralis, medial and lateral geniculate) mediate the perceptual processing of extrapersonal space; (2) the pre-motor cortex, the anterior cingulate gyrus, the basal ganglia and some thalamic nuclei (centromedian parafascicularis, ventral-anterior, ventral-lateral) participate in preparation and execution of motor responses in the extrapersonal space. The mesencephalic reticular formation and the nucleus reticularis thalami are components of both systems.

At the clinical level, distinctions have been drawn between symptoms of the neglect syndrome that may be traced back to the disruption of perceptual and pre-motor systems, respectively.

Perceptual Neglect. The patients’ failure to detect contralateral visual or somatosensory2 stimuli may be a manifestation of perceptual neglect, or hemi-inattention (Heilman et al., 1985a). Perceptual visual and somatosensory neglect simulates hemianaesthesia and hemianopia due to primary sensory deficits, however (see Heilman et al., 1985a; Kennard, 1939; Silberpfennig, 1941). A distinction between the sensory and perceptual components of these disorders cannot easily be drawn by clinical examination (but see Kooistra & Heilman, 1989 for the case of perceptual visual neglect vs hemianopia). The demonstration of preserved physiological responses (evoked potentials, skin conductance) to undetected tactile or visual stimuli indicates that hemianopia or hemianaesthesia may be due to perceptual neglect, rather than to a primary sensory disorder (Vallar et al., 1991a; 1991b).

The few published cases of patients with a left visual field deficit due, at least in part, to perceptual visual neglect, have had extensive anteroposterior or posterior lesions. The right sensory occipital cortex was spared in the two patients of Vallar et al. (1991b), who had normal evoked potentials to left visual field stimulation. The patient of Kooistra and Heilman (1989) had a right thalamic and medial temporo-occipital infarct. Similarly, the anatomical correlates of perceptual somatosensory neglect in the four cases of Vallar et al. (1991a; 1991b) were extensive antero-posterior or posterior lesions. As shown by the seminal case reports of Silberpfennig (1941), frontal lesions may also produce perceptual visual neglect, or, using his terminology, “pseudohemianopsia”. The association of a CT- or MRI-assessed lesion sparing the visual pathways and occipital cortex with a contralateral visual field deficit does not entirely rule out the possibility of a primary sensory disorder, however. Kuhl et al. (1980) have described a patient with a CT-assessed left frontal infarct and contralateral hemianopia: PET revealed hypometabolism not only in the infarcted area, but also in the left thalamus and primary visual cortex. Evidence of processing without awareness, such as normal evoked potentials to undetected stimuli, is therefore needed to conclude that the visual or somatosensory deficit is due, at least in part, to perceptual neglect.

Pre-motor Neglect. Pre-motor neglect (“unilateral, directional, or hemispatial hypokinesia”: Heilman et al., 1985a; Watson, Miller, & Heilman, 1978) refers to the patient’s reluctance to perform motor activities in the half-space contralateral to the lesion, with either limb, in the absence of primary motor deficits. The clinical exploratory tasks currently used to detect hemineglect do not dissociate the putative input and output factors of the deficit, requiring both a perceptual (visual, tactile-kinaesthetic) analysis of the environment and motor actions in the extrapersonal space. A number of paradigms have therefore been devised to decouple the perceptual and the pre-motor components of neglect. Such studies also provide some information concerning their anatomical correlates.

Heilman et al. (1985b) found that right brain-damaged patients with left neglect initiate motor responses towards the left hemi-space more slowly than towards the right hemispace. Their patients had extensive anteroposterior (three cases), parietal (two cases) and frontal (one case) lesions. Coslett et al. (1990) required their patients to bisect lines placed to the left or right of their body’s sagittal midplane, while monitoring their own performance on a TV screen placed in the left or right half-space (see a discussion of Coslett and co-workers’ paradigm in Bisiach, Geminiani, Berti, & Rusconi, 1990). In Coslett and co-workers’ series, the two patients (cases 1 and 2) with an hypokinetic deficit had antero-posterior lesions, and the one patient (case 3) with a perceptual deficit had a temporo-parietal lesion. The neglect patient F.S. of Bisiach, Berti and Vallar (1985), who had a right subcortical lesion involving the basal ganglia, the internal capsule and the frontal white matter, frequently failed to react to right-sided visual stimuli when he had to respond by pressing a key in the left half-space using the right unaffected hand. Furthermore, F.S.’s detection of left-sided stimuli, grossly defective when the response took place in the left half-space, improved with a right-sided response.

Bisiach et al. (1990) used a pulley device in order to dissociate the direction of visual attention from that of the arm movement in a line bisection task. They found that in the majority of patients, both the perceptual and the pre-motor deficits were determinants of left hemineglect, with an overall prevalence of the perceptual factor. They suggest a trend whereby pre-motor factors contribute to the bisection error of patients with CT-assessed cortical lesions including the frontal lobe more than to the error of patients with exclusively retro-rolandic lesions. The small number of patients (15 cases) and the absence of purely frontal cases prevent firm anatomo-clinical conclusions, however.

In a series of 18 right brain-damaged patients with neglect, Tegner and Levander (1991) decoupled the direction of visual exploration and of arm movement in a line cancellation task, by using a 90° angle mirror and preventing a direct view of the test sheet. As with Bisiach et al. (1990), Tegner and Levander suggest an association between lesions including the frontal lobe and directional hypokinesia, while the perceptual component of neglect would be produced by posterior damage.

In the study of Spiers et al. (1990), who found an association between EEG slowing in the right frontal areas and neglect, a visual exploratory test was used. Spiers et al. required their patients to scan a display and to point to the targets (“A” letters interspersed among other letters) with the hand ipsilateral to the injected hemisphere. This task, which does not dissociate the perceptual and the pre-motor factors of neglect, poses important motor demands (eye and arm movements). These may account for the involvement of the frontal lobe.

In a patient with a right-sided ischaemic lesion of the frontal lobe and the basal ganglia, Bottini, Sterzi and Vallar (1992) have shown a selective impairment in tasks requiring the motor exploration of extrapersonal space. The patient showed left visual hemineglect when pointing to targets by making use of the right hand. By contrast, she was entirely accurate when a naming response was required. The patient was also unimpaired on the Wundt-Jastrow illusion test, which involves a perceptual judgement about the length of two black fans, without any limb movement (Massironi et al., 1988).

The pre-motor component of neglect (directional hypokinesia) must be distinguished from motor neglect or négligence motrice (Castaigne, Laplane, & Degos, 1970; Critchley, 1953). Motor neglect refers to the patient’s unwillingness to move the limbs spontaneously contralateral to the lesion in both halves of space, in the absence of primary motor deficits. Patients are able to move the “neglected” limbs, however, when attention is specifically drawn to them by a verbal command. The absence or reduction of movements by the contralateral hand, which characterises motor neglect, lacks the hemispatial dimension of hemineglect, involving both halves of extrapersonal space. Motor neglect may occur in the absence of spatial hemineglect (Castaigne et al., 1970, 1972; de la Sayette et al., 1989; Laplane et al., 1982; Valenstein & Heilman, 1981; Viader, Cambier, & Pariser, 1982). The anatomical correlates of motor neglect include retro-rolandic and frontal left- and right-sided cortico-subcortical lesions (Castaigne et al., 1970, 1972; Laplane et al., 1977; Laplane & Degos, 1983). Right-sided subcortical lesions, involving the head of the caudate nucleus (Valenstein & Heilman, 1981), the anterior limb of the internal capsule (de la Sayette et al., 1989; Viader et al., 1982) and the thalamus (Laplane et al., 1982; Schott et al., 1981; Watson & Heilman, 1979) may also produce motor neglect. In a group study, Barbieri and De Renzi (1989) have confirmed that motor neglect may occur in the absence of spatial hemineglect, suggesting that the two disorders are not produced by the disruption of a single functional mechanism. They did, however, find an hemispheric asymmetry: left motor neglect was present in 5 out of 28 right brain-damaged patients with mild or no paresis, but not in the group of 50 left brain-damaged patients. All five patients with motor neglect had retro-rolandic lesions involving the right parietal lobe. The series of positive patients of Laplane and Degos (1983) included 12 right-sided and 8 left-sided lesions and in 15 out of 20 patients the frontal lobe was involved.

To summarise, unilateral directional hypokinesia is a discrete component deficit of spatial hemineglect, dissociable from perceptual hemispatial disorders. There is some indication that right frontal lesions may play a major role in producing this pre-motor disorder. Right parietal damage, by contrast, seems more closely associated with the perceptual aspects of neglect. Motor neglect is a space-independent disorder, that may occur in the absence of spatial hemineglect. The available anatomo-clinical correlation studies appear to indicate a more frequent association with right-sided subcortical and cortical (both anterior and posterior) lesions.

Extrapersonal vs Personal Components of Hemineglect

In the last 10 years, animal research has shown that lesions of different cerebral areas may produce neglect for the “far” vs “near” extrapersonal space (Rizzolatti et al., 1983; 1985). A broadly similar dissociation between “extrapersonal” vs “personal” neglect has been observed in humans (Bisiach et al., 1986a). In a patient with an extensive right temporo-parietal cortico-subcortical infarction, Halligan and Marshall (1991) showed neglect for “near” (within hand reach) but not “far” extrapersonal space in line bisection tasks. In man, these behavioural dissociations do not appear to have a clear-cut anatomical counterpart in that in the majority of cases the lesions involve the retro-rolandic areas, while some patients have subcortical lesions. However, firmer conclusions are prevented by the limited number of dissociated cases in whom anatomical data are available. The evaluation of this lack of anatomical dissociation in humans should also consider that, in the monkey, the differentiation of neglect for “far” and “near” space has been produced by small lesions of adjacent areas (see Rizzolatti et al., 1983). In contrast, the naturally occurring human lesions are typically much larger. It is finally worth noting that the differentiation of the anatomical correlates of the “pre-motor” vs “perceptual” components of hemineglect is a comparatively easier enterprise: The putatively involved cortical structures (i.e. the pre-motor frontal and the posterior-inferior parietal regions) are well separated spatially and are often damaged in isolation by naturally occurring lesions.

Neural Mechanisms of Recovery from Hemineglect

The notion that the neural correlates of spatial representation and awareness involve cortico-subcortical neural circuits may offer insight into the neural mechanisms of recovery. Recovery from hemineglect may be attributed either to the takeover by undamaged cerebral regions (or neural circuits) not primarily committed to spatial representation,3 or to the regression of diaschisis in areas far removed from, but connected with, the damaged region. According to this latter view, the neural correlates of cognitive functions are, as suggested in the previous sections, complex circuits: A deficit such as neglect reflects—in an early phase after stroke onset—both the structural damage and the dysfunction of remote areas, while recovery is based on restoration of neural activity in connected regions, not directly damaged by the lesion. The few empirical data concerning recovery from hemineglect are consistent with this hypothesis. In the study of Vallar et al. (1988), behavioural recovery from neglect in patients with subcortical lesions paralleled the reduction in hypoperfusion in the undamaged ipsilateral cortex. Similarly, in the monkey, recovery from neglect produced by cortical experimental lesions is associated with a reduction in hypometabolism in connected subcortical ipsilateral structures (Deuel, 1987). The conclusion that regression of diaschisis in ipsilateral regions connected with the structurally damaged areas is a relevant factor in recovery is not confined to neglect, but applies also to other neuropsychological deficits (aphasia: Perani et al., 1987; Vallar, 1991b), and extends to basic neurological disorders (hemiplegia: Dauth, Gilman, Frey, & Penney, 1985; Gilman, Dauth, Frey, & Penney, 1987; hemianopia: Bosley et al., 1987). In all these disorders, recovery was related to a more or less complete regression of hypoperfusion and hypometabolism in the undamaged cortical or subcortical regions of the affected hemisphere, connected with the area destroyed by the structural (natural or experimental) injury.

Also, the follow-up study of Hier, Mondlock and Caplan (1983) argues for a role of the ipsilateral undamaged regions of the right hemisphere, as lesion size and lobar sparing affected recovery rate, which was faster when the lesion was small and spared the frontal lobe. Levine, Warach, Benowitz and Calvanio (1986) have subsequently confirmed the negative effect of lesion size upon recovery from left spatial hemineglect in right braindamaged patients who have suffered a stroke. They have also found a negative effect of pre-morbid diffuse cortical atrophy. This latter observation is compatible with the view that the integrity of the left hemisphere is important for recovery from neglect, even though it does not provide direct relevant evidence.

In a series of chronic neglect patients, Cappa et al. (1991) found a significant correlation between severity of neglect and lesion volume in a letter cancellation task, but not between severity of neglect and cerebral atrophy. Cappa and co-workers’ data do not confirm the negative effect of cortical atrophy found by Levine et al. (1986). The two results are not directly comparable, however, since Cappa et al. did not undertake a follow-up study.

The lesion size effect found by Hier et al. (1983), Levine et al. (1986) and Cappa et al. (1991) is in line with animal data showing that in the monkey, small frontal lesions (Welch & Stuteville, 1958) produce a neglect deficit of shorter duration, as compared with extensive frontal damage (Deuel & Collins, 1983). Additional support for the role of the undamaged regions of the right hemisphere comes from a recent clinical observation by Daffner, Ahern, Weintraub & Mesulam (1990). A woman suffered a right frontal stroke producing severe left spatial hemineglect, from which she partially recovered. Twenty days later, she had a second stroke in the right parietal lobe, resulting in a worsening of the left neglect.

Hier and co-workers’ (1983) finding that recovery from neglect is more rapid and complete than recovery from more basic neurological deficits (e.g. hemiplegia, hemianopia) may be taken as an indication that the neural networks involved in spatial representation are more extensive and redundant than those devoted to primary somatosensory functions. This conclusion comports with the clinical observation (see p.29–36) that a variety of cortical and subcortical lesion sites may be associated with spatial hemineglect.

The empirical evidence reviewed above does not rule out the possibility that regions of the hemisphere contralateral to the cerebral lesion contribute to recovery. A main source of difficulty for the evaluation of the role of the undamaged hemisphere in recovery from hemineglect in humans is that, at variance with the case of aphasia, successive lesions do not provide clear-cut information. In left brain-damaged aphasic patients, a second lesion in the right hemisphere may yield a worsening of the (more or less recovered) aphasic disorder, suggesting a right hemisphere contribution to recovered or residual language (for a review, see Vallar, 1991b). In the case of spatial exploratory disorders, however, bilateral posterior parieto-occipital lesions are associated with global non-lateralised deficits, often collected under the rubric of Balint’s syndrome (for a review, see De Renzi, 1982). Recently, neglect has been reported to occur after bilateral posterior lesions, but the deficit is bilateral, involving the lower half-space (altitudinal neglect: Butters, Evans, Kirsch, & Kewman, 1989; Rapcsak, Cimino, & Heilman, 1988). Data of this sort are compatible with the view that the undamaged hemisphere may contribute to behavioural recovery, but do not provide direct evidence favouring such a conclusion, since the bilateral damage is associated with qualitatively different disorders, rather than with a worsening of the lateralised deficit. The observation that even in patients with extensive antero-posterior cortico-subcortical lesions, vestibular stimulation may produce a temporary amelioration of contralateral hemineglect and hemianaethesia, suggests an involvement of the undamaged left hemisphere (Cappa et al., 1987; Vallar et al., 1990), even though this finding cannot be regarded as direct evidence.

Further indirect evidence for a contribution of the undamaged hemisphere to recovery comes from the clinical observation that conjugate eye deviation towards the lesion side, a disorder closely related with right-sided lesions and hemineglect (see De Renzi, Colombo, Faglioni, & Gibertoni, 1982; Marquardsen, 1969; Tijssen, van Gisbergen, & Schulte, 1991), lasts longer in stroke patients with a pre-existing contralateral lesion involving the frontal lobe, as compared with patients in whom the contralateral hemisphere is unaffected (Steiner & Melamed, 1984; see related data in monkeys with bilateral successive lesions of the frontal eye fields in Latto & Cowey, 1971a; 1971b).

Animal experiments involving commissurotomy argue for a contribution of the undamaged hemisphere. In the monkey, unilateral lesions of the frontal eye fields disrupt reaching of visual targets and the deficit is more severe for contralateral stimuli (Crowne, Yeo, & Steele Russell, 1981). This impairment, which recovers over time, may be temporarily restored by commissurotomy. This indicates a role of the undamaged hemisphere, via the callosal commissures, in the recovery process. Also, the deficit produced by the callosal section lessens over time, suggesting that the availability of the callosal pathways is not essential for recovery. This conclusion is supported by the observation that in monkeys a pre-existing commissurotomy does not affect recovery rate from neglect produced by a unilateral frontal lesion. Monkeys who had suffered a commissurotomy before the frontal lesion show a more severe deficit, however (Watson, Valenstein, Day, & Heilman, 1984).

Finally, as some reduction of metabolism occurs also in the hemisphere contralateral to the lesion (see p. 37), regression of diaschisis may be a relevant factor in determining the contribution of the unaffected hemisphere to recovery. Perani et al. (in press) have recently undertaken a PET-neuropsychological follow-up study in a right brain-damaged patient with a CT-assessed subcortical lesion, who recovered from neglect and sensorimotor neurological deficits. In the acute stage (3 days after stroke onset), PET showed hypometabolism in the structurally undamaged cortex of the right hemisphere and in the left hemisphere. Eight months later, glucose metabolism had improved in both hemispheres, paralleling behavioural recovery. In contrast, in a patient with an extensive infarction in the vascular territories of the middle and posterior cerebral arteries, a severe neglect was still present 4 months post-onset, associated with a persistent reduction of metabolic activity in both hemispheres.

In the last few years, behavioural techniques for the rehabilitation of spatial hemineglect have been devised (see Pizzamiglio et al., 1990). Two recent studies provide some limited information concerning the neural correlates of the behavioural effects of rehabilitation. In the neglect patients of Cappa et al. (1991), the rehabilitation training produced an improvement in scanning performance, which was related neither to lesion volume nor to cerebral atrophy. Pantano et al. (1992) measured rCBF by SPECT in right brain-damaged patients with neglect before and after 2 months rehabilitation treatment. They found a significant correlation between behavioural recovery from hemineglect and increase in rCBF in the anterior regions of the left hemisphere and suggest participation of the left frontal areas in the recovery process induced by the treatment.

Summary

1. Anatomo-clinical studies in brain-damaged patients suffering from spatial hemineglect suggest that the neural correlates of spatial representation and awareness should be conceived of in terms of complex cortico-subcortical neural circuits. This conclusion is supported by the observation that, both in humans and in animals, a variety of cortical and subcortical lesions may be associated with neglect, and, more directly, by the finding of correlations between neglect and functional derangement in cerebral regions far removed from, but connected with, the structurally damaged areas. In humans, the right inferior-posterior parietal regions and, possibly, the posterior and medial portions of the thalamus and their connections play a very important role. The network committed to spatial representation is more widespread, however, including, among other structures, the premotor frontal cortex.

2. Behavioural studies in patients with spatial hemineglect suggest that these disorders, like other neuropsychological deficits, are not unitary in nature. Distinctions between perceptual and pre-motor, personal and extrapersonal components of neglect have been drawn. Animal and human data studies suggest the possibility of a correspondence between some of these behavioural dissociations and discrete anatomical lesional correlates. Studies in the monkey have shown that different aspects of neglect, such as the peripersonal vs extrapersonal space dissociation, may be related to the disruption of different neural circuits. The observation of behavioural dissociations in humans, together with the (admittedly limited) evidence that the anatomical correlates of specific manifestations of the neglect syndrome may be different, is compatible with a multiple circuit approach.

3. The few available studies concerning the neural mechanisms of recovery from hemineglect are also consistent with a network view of the neural correlates of spatial representation and awareness. Regression of diaschisis in undamaged portions of the relevant neural circuits in both the affected and the contralateral hemisphere and size of the structural lesion are important factors underlying behavioural recovery.

Acknowledgements

This chapter has benefited from the comments of Edoardo Bisiach, who kindly read an earlier version of the manuscript, and the editors. This work was supported by a CNR grant.

Adams, R.D. & Victor, M. (1985). Principles of neurology, 3rd edn. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Andrews, R.J. (1991). Transhemispheric diaschisis. A review and comment. Stroke, 22, 943–949.

Barbas, H. & Mesulam, M.M. (1981). Organization of afferent input to subdivisions of area 8 in the rhesus monkey. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 200, 407–431.

Barbieri, C. & De Renzi, E. (1989). Patterns of neglect dissociations. Behavioral Neurology, 2, 13–24.

Battersby, W.S., Bender, M.B., Pollack, M., & Kahn, R.L. (1956). Unilateral “spatial agnosia” (“inattention”) in patients with cerebral lesions. Brain, 79, 68–93.

Bisiach, E., Berti, A., & Vallar, G. (1985). Analogical and logical disorders of space. In M.I. Posner & O.S.M. Marin (Eds), Attention and performance XI, pp. 239–249. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Bisiach, E., Capitani, E., Luzzatti, C., & Perani, D. (1981). Brain and conscious representation of outside reality. Neuropsychologia, 19, 543–551.

Bisiach, E., Cornacchia, L., Sterzi, R., & Vallar, G. (1984). Disorders of perceived auditory lateralization after lesions of the right hemisphere. Brain, 107, 37–52.

Bisiach, E., Geminiani, G., Berti, A., & Rusconi, M.L. (1990). Perceptual and premotor factors of unilateral neglect. Neurology, 40, 1278–1281.

Bisiach, E., Perani, D., Vallar, G., & Berti, A. (1986a). Unilateral neglect: Personal and extrapersonal. Neuropsychologia, 24, 759–767.

Bisiach, E. Vallar, G. (1988). Hemineglect in humans. In F. Boiler & J. Grafman (Eds), Handbook of neuropsychology, Vol. 1, pp. 195–222. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Bisiach, E., Vallar, G., Perani, D., Papagno, C., & Berti, A. (1986b). Unawareness of disease following lesions of the right hemisphere: Anosognosia for hemiplegia and anosognosia for hemianopia. Neuropsychologia, 24, 471–482.

Bogousslavsky, J., Miklossy, J., Regli, F., Deruaz, J.P., Assal, G., & Delaloye, B. (1988a). Subcortical neglect: Neuropsychological, SPECT, and neuropathological correlations with anterior choroidal artery territory infarction. Annals of Neurology, 23, 448–452.

Bogousslavsky, J., Regli, F., & Uske, A. (1988b). Thalamic infarcts: Clinical syndromes, etiology and prognosis. Neurology, 38, 837–848.

Bosley, T.M., Dann, R., Silver, F.L., Alavi, A., Kushner, M., Chawluk, J.B., Savino, P.J., Sergott, R.C., Schatz, N.J., & Reivich, M. (1987). Recovery of vision after ischemic lesions: Positron emission tomography. Annals of Neurology, 21, 444–450.

Bottini, G., Sterzi, R., & Vallar, G. (1992). Directional hypokinesia in spatial hemineglect: A case study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 55, 562–565.

Brain, W.R. (1941). Visual disorientation with special reference to lesions of the right cerebral hemisphere. Brain, 64, 244–272.

Butters, C.M., Evans, J., Kirsch, N., & Kewman, D. (1989). Altitudinal neglect following traumatic brain injury: A case report. Cortex, 25, 135–146.

Cambier, J., Elghozi, D., & Strube, E. (1980). Lésion du thalamus droit avec syndrome de l’hémisphère mineur: Discussion du concept de négligence thalamique. Revue Neurologique, 136, 105–116.

Cambier, J., Graveleau, P., Decroix, J.P., Elghozi, D., & Masson, M. (1983). La syndrome de I’artére choroidienne antérieure: Étude neuropsychologique de 4 cas. Revue Neurologique, 139, 553–559.

Cappa, S., Sterzi, R., Vallar, G., & Bisiach, E. (1987). Remission of hemineglect and anosognosia after vestibular stimulation. Neuropsychologia, 25, 775–782.

Cappa, S.F., Guariglia, C., Messa, C., Pizzamiglio. L., & Zoccolotti, P.L. (1991). CT-scan correlates of chronic unilateral neglect. Neuropsychology, 5, 195–204.

Cappa, S.F., Papagno, C., Vallar, G., & Vignolo, L.A. (1986). Aphasia does not always follow left thalamic hemorrhage: A study of five negative cases. Cortex, 22, 639–647.

Cappa, S.F., & Vallar, G. (1992). Neuropsychological disorders after subcortical lesions: Implications for neural models of language and spatial attention. In G. Vallar, S.F. Cappa. & C.W. Wallesch (Eds), Neuropsychological disorders associated with subcortical lesions, pp.7–41. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Castaigne, P., Laplane, D., & Degos, J.D. (1970). Trois cas de negligence motrice par lesion retro-rolandique. Revue Neurologique, 122, 234–242.

Castaigne, P., Laplane, D., & Degos, J.D. (1972). Trois cas de negligence motrice par lesion frontale pre-rolandique. Revue Neurologique, 126, 5–15.

Celesia, G.G., Polcyn, RE., Holden, J.E., Nickles, R.J., Koeppe, R.A., & Gatley, S.J. (1984). Determination of regional cerebral blood flow in patients with cerebral infarction: Use of fluoromethane labeled with fluorine 18 and positron emission tomography. Archives of Neurology. 41, 262–267’.

Changeux, J.P. & Dehaene, S. (1989). Neuronal models of cognitive functions. Cognition, 33. 63–109.

Colombo, A., De Renzi, E., & Gentilini, M. (1982). The time course of visual hemi-inattention. Archiv fur Psychiatric und Nervenkrankheiten, 231, 539 546.

Coslett, H.B., Bowers, D., Fitzpatrick, E., Haws, B., & Heilman, K.M. (1990). Directional hypokinesia and hemispatial inattention in neglect. Brain, 113, 475^186.

Critchley, M. (1953). The parietal lobes. London: Hafner Press.

Crowne, D.P., Yeo, C.H., & Steele Russell, I. (1981). The effects of unilateral frontal eye field lesions in the monkey: Visual-motor guidance and avoidance behaviour. Behavioral Bruin Research, 2, 165–187.

Daffner. K.R., Ahern, G.L., Weintraub, S., & Mesulam, M.M. (1990). Dissociated neglect behavior following sequential strokes in the right hemisphere. Annals of Neurology, 28, 97–101.

Damasio, A.R., Damasio, H., & Chang Chui, H. (1980). Neglect following damage to frontal lobe or basal ganglia. Neuropsychologia. 18, 123–132.

Damasio, H. (1983). A computed tomographic guide to the identification of cerebral vascular territories. Archives of Neurology, 40, 138–142.

Dauth, G.W., Gilman. S., Frey. K.A., & Penney, J.B. (1985). Basal ganglia glucose utilization after recent precentral ablation in the monkey. Annuls of Neurology, 17. 431–438.

de la Sayette, V., Bouvard, G., Eustache, F., Chapon, F., Rivaton, F., Viader. F., & Lechevalier, B. (1989). Infarct of the anterior limb of the right internal capsule causing left motor neglect: Case report and cerebral blood flow study. Cortex, 25. 147–154.

Denny-Brown, D. & Chambers, R.A. (1958). The parietal lobe and behavior. Research Publications. Association for Research in Nervous and Mental Disease. 36. 35–117.

De Renzi, E. (1982). Disorders of space exploration and cognition. Chichester: John Wiley.

De Renzi, E., Colombo, A., Faglioni, P., & Gibertoni, M. (1982). Conjugate gaze paresis in stroke patients with unilateral damage: An unexpected instance of hemispheric asymmetry. Archives of Neurology. 39, 482–486.

Deuel, R.K. (1987). Neural dysfunction during hemineglect after cortical damage in two monkey models. In M. Jeannerod (Ed.). Neurophysiological and neuropsychological aspects of spatial neglect, pp. 315–344. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Deuel, R.K. & Collins, R.C. (1983). Recovery from unilateral neglect. Experimental Neurology, 81, 733–748.

Deuel, R.K. & Collins. R.C. (1984). The functional anatomy of frontal lobe neglect in the monkey: Behavioral and quantitative 2-deoxyglucose studies. Annals of Neurology. 15, 521 529.

Dobkin, J.A., Levine, R.L., Lagreze. H.L.. Dulli. DA., Nickles. R.J., & Rowc.

B.R. (1989). Evidence for transhemispheric diaschisis in unilateral stroke. Archives of Neurology, 46, 1333–1336.

Ettlinger, G. (1984). Humans, apes and monkeys: The changing neuropsychological viewpoint. Neuropsychologic, 22, 685–696.

Feeney, D.M. & Baron, J.C. (1986). Diaschisis. Stroke, 17, 817–830.

Ferro, J.M. & Kertesz, A. (1984). Posterior internal capsule infarction associated with neglect. Archives of Neurology, 41, 422-^124.

Ferro, J.M., Kertesz, A., & Black, S.E. (1987). Subcortical neglect: Quantitation, anatomy, and recovery. Neurology, 37, 1487–1492.

Foote, S.L. & Morrison, J.H. (1987). Extrathalamic modulation of cortical function. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 10, 67–95.

Franck, G., Salmon, E., Sadzot, B., & Van der Linden, M.E. (1986). Etude hemodynamique et metabolique par tomographic a emission de positons d’un cas d’atteinte ischemique thalamocapsulaire droite. Revue Neurologique. 142. 475–479.

Fromm, D., Holland, A.J., Swindell, C.S., & Reinmuth, O.M. (1985). Various consequences of subcortical stroke: Prospective study of 16 consecutive cases. Archives of Neurology, 42. 943–950.

Getting, P.A. (1989). Emerging principles governing the operation of neural networks. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 12. 185–204.

Gilman, S., Dauth, G.W., Frey, K.A., & Penney, J.B. (1987). Experimental hemiplegia in the monkey: Basal ganglia glucose activity during recovery. Annals of Neurology, 22, 370–376.

Ginsberg, M.D., Reivich, M., Giandomenico, A., & Greenberg, J.H. (1977). Local glucose utilization in acute focal cerebral ischemia: Local dysmetabolism and diaschisis. Neurology. 27, 1042–1048.

Girault, J.A., Savaki, H.E., Desban, M., Giowinsky, J., & Besson. M.J. (1985). Bilateral cerebral metabolic alterations following lesions of the ventromedial thalamic nucleus: Mapping by the 14C-deoxyglucose method in conscious rats. Journal of Comparative Neurology, 231, 137–149.

Gowers, W.R. (1895). Manuale cklle malattie del sis tenia nervosa (Italian translation). Milano: Vallardi.

Graff-Radford, N.R., Damasio. H., Yamada, T., Eslinger, P.J., & Damasio. A.R. (1985). Nonhaemorrhagic thalamic infarction: Clinical, neuropsychological and electrophysiological findings in four anatomical groups defined by computerized tomography. Brain, 108, 485–516.

Graff-Radford, N.R., Tranel, D., Van Hoesen, G.W . & Brandt. J.P. (1990). Diencephalic amnesia. Brain, 113. 1–25.

Halligan, P.W. & Marshall, J.C. (1991). Left neglect for near but not far space in man. Nature. 350, 498–500.

Halligan, P. W., Marshall, J.C., & Wade, D.T. (1990). Do visual field deficits exacerbate visuo-spatial neglect? Journal of Neurology. Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 53. 487–491.

Hassler. R. (1979). Striatal regulation of adverting and attention directing induced by pallidal stimulation. Applied Neurophysiology. 42. 98 -102.

Healton, E.B., Navarro, C., Bressman, S., & Brust, J.C.M. (1982). Subcortical neglect. Neurology, 32, 776–778.

Hecaen. H. (1962). Clinical symptomatology in right and left hemispheric lesions. In V.B. Mountcastle (Ed.), Interhemispheric relations and cerebral dominance, pp. 215–243. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hecaen, H. (1972). Introduction a la neuropsychologic. Paris: Larousse.

Hecaen. H., Penfield, W., Bertrand. C. & Malmo. R. (1956). The syndrome of apractoagnosia due to lesions of the minor cerebral hemisphere. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry. 75. 400^34.

Heilman, K.M., Bowers, D., Coslett. H.B., Whelan, H., & Watson, R.T. (1985b). Directional hypokinesia: Prolonged reaction times for leftward movements in patients with right hemisphere lesions and neglect. Neurology, 35, 855–859.

Heilman, K.M. & Valenstein, E. (1972a). Frontal lobe neglect in man. Neurology, 22, 660–664.

Heilman, K.M. & Valenstein, E. (1972b). Auditory neglect in man. Archives of Neurology, 26, 32–35.

Heilman, K.M., Watson, R.T., & Valenstein, E. (1985a). Neglect and related disorders. In K.M. Heilman & E. Valenstein (Eds), Clinical neuropsychology, 2nd edn, pp. 243–293. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hier, D.B., Davis, K.R., Richardson, E.P., & Mohr, J.P. (1977). Hypertensive putaminal hemorrhage. Annals of Neurology, 1. 152 159.

Hier, D.B., Mondlock, J., & Caplan. L.R. (1983). Recovery of behavioral abnormalities after right hemisphere stoke. Neurology. 33. 345–350.

Hirose. G., Kosoegawa. H., Saeki, M., Kitagawa. Y., Oda. R., Kanda, S., & Matsuhira, T. (1985). The syndrome of posterior thalamic hemorrhage. Neurology, 35, 998–1002.

Hyvarinen, J. (1982). The parietal cortex of monkey and man. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Jewesbury, E.C.O. (1969). Parietal lobe syndromes. In P.J. Vinken & G.W. Bruyn (Eds), Handbook of clinical neurology. Vol. 2, pp.680–699. Amsterdam: North-Holland.

Kennard, M.A. (1939). Alterations in response to visual stimuli following lesions of frontal lobe in monkeys. Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry, 41, 1153–1165.

Kertesz, A. & Dobrowolsky, S. (1981). Right-hemisphere deficits, lesion size and location. Journal of Clinical Neuropsychology, 3, 283–299.

Kiyosawa, M., Baron, J.C., Hamel, E., Pappata, S., Duverger, D., Riche, D., Mazoyer, B., Naquet, R., & MacKenzie, E.T. (1989). Time course of effects of lesions of the nucleus basalis of Maynert on glucose utilization by the cerebral cortex: Positron tomography in baboons. Brain, 112, 435–455.

Koehler, P.J., Endtz, L.J., Te Velde, J., & Hekster, R.E.M. (1986). Aware or non-aware: On the significance of awareness for the localization of the lesion responsible for homonymous hemianopia. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 75, 255–262.

Kooistra, C.A. & Heilman, K.M. (1989). Hemispatial visual inattention masquerading as hemianopia. Neurology, 39, 1125–1127.

Kuhl, D.E., Phelps, M.E., Kowell, A.P., Metter, E.J., Selin, C., & Winter, J. (1980). Effects of stroke on local cerebral metabolism and perfusion: Mapping by emission computed tomography of 18FDG and 13NH3. Annals of Neurology, 8. 47–60.

Laplane, D. & Degos, J.D. (1983). Motor neglect. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 46, 152–158.

Laplane, D., Escourolle, R., Degos, J.D., Sauron, B., & Massiou, H. (1982). La negligence motrice d’origine thalamique. Revue Neurologique, 138, 201–211.

Laplane, D., Talairach, J., Meininger, V., Bancaud, J., & Orgogozo, J.M. (1977). Clinical consequences of corticectomies involving the supplementary motor area in man. Journal of the Neurological Sciences, 34, 301–314.

Latto, R. & Cowey, A. (1971a). Visual field defects after frontal eye-field lesions in monkeys. Brain Research. 30. 1–25.

Latto, R. & Cowey. A. (1971b). Fixation changes after frontal eye-field lesions in monkeys. Brain Research, 30, 25–36.

Levine. D.N., Kaufman. K.J., & Mohr, J.P. (1978). Inaccurate reaching associated with a superior parietal lobe tumor. Neurology, 28, 556–561.

Levine. D.N., Warach. J.D., Benowitz, L., & Calvanio, R. (1986). Left spatial neglect: Effects of lesion size and premorbid brain atrophy on severity and recovery following right cerebral infarction. Neurology, 36, 362–366.

London, E.D., McKinney, M., Dam, M., Ellis. A., & Coyle. J.T. (1984). Decreased cortical glucose utilization after ibotenate lesion of the rat ventromedial globus pallidus. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 4, 381–390.

Lynch, J.C. (1980). The functional organization of the posterior parietal association cortex. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 3. 485–534.

Lynch, J.C. & McLaren, J.W. (1989). Deficits of visual attention and saccadic eye movements after lesions of parieto-occipital cortex in monkeys. Journal of Neurophysiology, 61. 74–90.

Marquardsen, J. (1969). The natural history of acute cerebrovascular disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 45, (suppl. 38).

Massironi, M., Antonucci. G., Pizzamiglio, L., Vitale, M.V., & Zoccolotti, P. (1988). The Wundt-Jastrow illusion in the study of spatial hemi-inattention. Neuropsychologia. 26, 161–166.

Masson, M., Decroix, J.P., Henin. D., Dairou, R., Graveleau, P., & Cambier, J. (1983). Syndrome de Tartere choroidienne anterieure: Etude clinique et tomodensitome-trique de 4 cas. Revue Neurologique, 139, 547–552.

McFie, J., Piercy, M.F., & Zangwill, O.L. (1950). Visual-spatial agnosia associated with lesions of the right cerebral hemisphere. Brain, 73, 167–190.

Mesulam, M.M. (1981). A cortical network for directed attention and unilateral neglect. Annals of Neurology, 10, 309–325.