3

KEEPING UP WITH THE VIRTUAL VOICE OF THE CUSTOMER—SOCIAL MEDIA APPLICATIONS IN PRODUCT INNOVATION

Anna Dubiel

WHU – Otto Beisheim School of Management

Tim Oliver Brexendorf

WHU – Otto Beisheim School of Management

Sebastian Glöckner

WHU – Otto Beisheim School of Management

3.1 Introduction

The development of market-oriented new products with a clearly defined, unique selling proposition is vital for successful innovators. Products that do not meet customer needs at competitive prices fail. Traditionally, in-house R&D departments using the firm's proprietary resources were solely responsible for delivering a steady stream of such new products. Several well-known R&D institutions like AT&T's Bell Labs and Xerox's Palo Alto Research Center provide evidence to the viability of such an internal R&D strategy. In the last two decades, however, pioneering firms like P&G and 3M have realized that there is vast additional innovation potential dozing outside the company walls. Tapping external stakeholders as a complementary source of innovation and thus opening up a firm's new product development (NPD) activities is becoming increasingly important today. Mobilizing customers, suppliers, or outside researchers helps to better develop new products and thus minimize failure risk. Among such external stakeholders, customers are often key actors. However, listening to the voice of the customer (VoC) poses serious challenges to NPD teams, because identifying the needs of the customer and subsequently deriving the decisive ones is costly and time consuming. First and foremost, choosing the “right” customer or gaining direct access to the end customer is anything but trivial. A potential solution might be a selection of online tools, allowing for a more efficient and direct customer involvement than is possible with offline solutions.

A recent and increasingly important opportunity to virtually integrate customers is through social media, which have developed rapidly in recent years. A prominent example of social media is Facebook, the worldwide social network, which has grown since its conception in 2004 to 1.1 billion users in 2013. Similarly, Twitter, a microblog service, had 1.7 billion registered users in the fall of 2013. It is no wonder that many firms want to mobilize these (potential) customer groups for their NPD activities (Markham and Lee, 2013). Analogous to “offline” customers, online customers can be particularly helpful in gathering new product ideas and in sharing their specific needs with the respective firm. In addition, the exchange of information with social media users can be very direct and instantaneous, and can be carried out at a relatively modest cost. However, while listening to the VoC during NPD is a standard practice for successful innovators, doing this with online tools still seems to be the exception rather than the rule. For instance, a recent German research study in the consumer goods and services industries reveals that more than half of the responding firms have never integrated customers by means of virtual tools into any NPD activity (Bartl et al., 2012). In a similar vein, Verhoef and colleagues (2013) reason that about half of such joint customer-firm NPD initiatives fail, an exemplary cause being customers “hijacking” these programs and ridiculing the firm instead of providing “serious” feedback. However, the recent PDMA Comparative Performance Assessment Study shows that successful innovators use social media to a considerably higher extent than less successful firms (Markham and Lee, 2013). Clearly, social media applications—as a subgroup of potential virtual transmitters of the VoC—are posing challenges for firms. However, existing, tentative evidence shows that their proper use in NPD can help firms to perform better.

In this chapter, we discuss social media applications and their role in NPD. First, we briefly explain the role VoC plays in achieving NPD success and introduce the most important social media applications. Second, we go on to introduce three levels of social media integration in NPD, analyzed from the firm's perspective: Level 1 represents a rather passive involvement through observation of social media content, Level 2 describes a more active participation on third parties' platforms under the firm's own name, and finally, Level 3 consists of designing proprietary social media content and proactively addressing the customer. In doing so, we present the most popular tools that allow the NPD team and the customer to communicate and work together. Additionally, we provide illustrative examples of the use of these tools. Finally, we end our chapter with a set of lessons learned from these cases. The latter are meant to provide guidelines for firms planning to use social media in their NPD processes. Due to the nature of our examples and the idiosyncrasies of the social media context, our chapter primarily targets the needs of business-to-consumer industries, in particular fast moving consumer goods (FMCG) manufacturers.

3.2 The Voice of the Virtual Customer

Academic studies and managerial experience both show that involving (potential) customers more closely during the NPD process can help develop products that are valued by their users. First and foremost, firms that integrate their customers report efficiency gains such as shorter innovation cycles and increased customer retention (Bartl et al., 2012). This is because customers are often experts in specific fields of knowledge and are able to make valuable NPD contributions. In particular, information about customer wants and needs is of utmost importance (Griffin, 2013).

More specifically, academic research shows that engaging customers in NPD is most promising at the beginning and in later stages of the NPD process (Gruner and Homburg, 2000). For instance, end users provide the majority of new product ideas sourced from outside the firm (Crawford and Di Benedetto, 2011). Similarly, they can help evaluate initial product concepts and align NPD better with market requirements. Customer involvement also is important during commercialization steps, because it helps to fine tune the product, improve product positioning, and develop a better market introduction strategy (Gruner and Homburg, 2000).

Luckily, customers are often willing to share their knowledge, creativity, and judgment to help their preferred firm to develop the products they demand. Moreover, many of them are willing to provide their input for free, or for nonmonetary rewards such as a letter of recognition or appreciation. Others are eager to design their own product and subsequently buy their product from the firm for a higher price than a noncustomized product.

The main challenge associated with consumers is that they often have problems expressing their latent needs or providing solutions on their own. Quality, quantity, and variety of input tend to vary among customers and, over time, of their engagement in NPD (Verhoef et al., 2013). Frequently, only incremental innovations stem from these efforts.

3.3 The Social Media Phenomenon

Relevance and Definition of Social Media

In recent years, social media applications such as Facebook and Twitter have emerged as increasingly influential web platforms for firms and consumers alike. Currently, consumers spend around 25 percent of their Internet time on social media sites (Wilcox and Stephen, 2013) and many social media applications have become ubiquitous. Social media—as a specific type of media—can be defined as a set of web- and mobile-based Internet applications that allow the creation, exchange, and consumption of content, and that enable connections between different (groups of) users and entities (Hoffman, Novak, and Stein, 2012). As such, social media blends technology and social interaction to create value jointly. People use social media primarily to connect with each other (e.g., sharing and socializing, achieving social goals, and interacting with peers) and/or to interact directly with content included in social media (e.g., exploring and learning, achieving knowledge and content goals, and exchanging information with social media) (Hoffman et al., 2012). As such, social media can be characterized by the participation and content generation of users, the networking effects between users, and also by their scalability. User participation, the development of user-generated content, the occurrence of network effects, and the ability to grow and expand capacity enable firms to leverage the value of crowdsourcing (the aggregated insights of numerous people), and to benefit from the collective wisdom of the crowd.

Forms of Social Media

Social media has many forms, which are in a constant flux. Popular (but partly overlapping) categories are social communities, social publishing, social commerce, and social entertainment (Tuten and Solomon, 2013).

Social communities are channels of social media focused on the relationship between users, emphasizing the users' contribution and the sharing of experience in the context of a community. They include social networking sites (e.g., Facebook, Google+, LinkedIn), message boards (e.g., Peachhead), and forums (e.g., CarForums.com).

Social publishing supports the dissemination of content to other users. This category includes blogs (e.g., bryanboy.com, notwithoutsalt.com), microsharing sites, also called microblogging (e.g., Twitter), and media sharing sites (e.g., Flickr, YouTube).

Social commerce media enhance the online buying and selling of products and services. Well-known examples include review and rating sites (e.g., Amazon, TripAdvisor), deal sites and deal aggregators (e.g., Groupon), social shopping markets (e.g., Facebook Connect), and social storefronts (e.g., Payvment).

Finally, social entertainment includes channels of social media that offer games and enjoyment. Social games (e.g., FarmVille), virtual worlds (e.g., Second Life), and entertainment communities (e.g., Myspace) are representatives of this type of site.

Moreover, the social media universe has experienced a considerable internationalization in the last decade with many country-specific applications mushrooming. Prominent examples are Xing, a large social community in Germany and Weibo, the largest Chinese microblogging application. Table 3.1 provides an overview of the various social media applications.

Table 3.1 Overview of Social Media Forms, Categories, and Applications

| Platform Type | Application Examples | Short Description |

| Social communities | ||

| Social networking sites | Members have their own profiles to share information, and to connect and communicate with other users and firms. People on these sites frequently share information through posts, links, photos, video, and other forms of multimedia. | |

| Forums/bulletin boards | CarForums.com | Members can add their own topics and answer questions posted by other members. Usually everybody is allowed to read everything. |

| Social publishing | ||

| Blogs | notwithoutsalt.com | Members can post articles that can be read and posted for people to read and to hold conversations by posting messages. These comments on blogs are similar to forums except they are attached to the owner of the blog and the discussion usually centers on the specific topic of the blog. |

| Microblogs | Members can send and read short updates to anyone subscribed to receive these updates. | |

| Media sharing | Flickr, YouTube | Members can upload and share various media, such as pictures and videos. Most types have additional social features, such as profiles and commenting. |

| Social commerce | ||

| Review and ratings | Amazon, TripAdvisor, yelp | Members can post opinions and review offers. Based on these, people can find and discover specific businesses. |

| Deal sites and aggregators | Groupon | Members can collect deals easily and fast from a number of popular and lesser-known sites in one place. They can browse through all the deals currently being offered. |

| Social shopping markets | Wanelo on Facebook | Members can sell and buy products through a store via a social networking shopping mall that is integrated in social media pages. |

| Social storefronts | CoreCommerce or Volusion on Facebook | Members can showcase items via specific applications of their own online store on social media pages. Interested customers are directed to this store URL, like Amazon or eBay, where the transaction will be completed. |

| Social entertainment | ||

| Social games | FarmVille | Members can play games embedded in social networks with each other and exchange information. |

| Virtual worlds | Second Life | Members can interact and communicate via avatars in a virtual world. |

| Entertainment communities | Myspace | Members can publish their own movies, pictures, opinions, and comments on entertainment platforms. |

3.4 Social Media in New Product Development

General Overview

There are many ways a company can leverage the power of social media. Today, there are not only millions of customers willingly sharing their product experiences, opinions, and desires online, but also many platforms that facilitate getting in touch with them. The latter are in particular social communities, social publishing and social commerce applications. Social entertainment seems generally less suited for direct NPD input. Before starting to leverage social media for NPD, it might also prove beneficial for firms to decide from which type of customer it would be most helpful to obtain specific input. Is the mass end user, the lead user—a person ahead of market trends having a high personal stake in pushing particular innovation ahead—the opinion leader or even the nonuser1 (Crawford and di Benedetto, 2011)?

To help managers decide to what extent they should involve social media in NPD, we describe three different levels of engagement. As a starting point, and without huge investment, a firm can simply collect, evaluate, and use online data that are already available. Products and product-related issues are discussed in numerous bulletin boards, discussion forums, blogs, and other online platforms. With no more than an Internet-capable computer and a search engine, a company can—even without disclosing its identity—find out what customers think about its products and identify the problems they encounter. We classify such pure listening to customers as Level 1 because it requires the lowest effort and investment.

Of course, a firm can also leverage input from social media applications more proactively. The company can, for example, create its own accounts in bulletin boards, forums, and social networks and can, as a result, discuss product-related issues with customers reciprocally and in more detail. This way, it can gain deeper insights into customers' wants and needs. As doing this requires more engagement on the part of the firm, we classify this as Level 2.

Finally, the standardized social media tools offered by popular applications may not satisfy the NPD needs of all firms. Thus at Level 3, the firms design their own social media tools. These go beyond simply posting voting options on their Facebook pages and encompass, for instance, custom-made toolkits supporting contests for customers to create their own ideas. On the one hand, this approach allows highly customized workflows and diverse customer-interaction modes; while on the other hand, it increases costs and demands considerable commitment.

Level 1: Listening to Customers

Because customers already communicate online—in freely accessible settings—about the pros and cons of existing products or their unmet needs, a firm can simply tune in to these exchanges. Different customer groups can provide very different input. The “typical” mass end user usually seeks help online regarding a specific question about utilization. The customer wants to satisfy a particular need with a product he or she plans to buy or has already bought. Typically, this customer can be found on Internet discussion boards. There, among fellow customers and without the intention of reaching a broader audience, the customer looks for a solution to his problem. By following such discussions, the firm is able to learn about genuine issues with products that are in use, product-related problems, and the relative value of products marketed in a certain category.

However, some mass end users actively seek a broader audience and maintain blogs (e.g., Dooce, Treehugger), create podcasts (e.g., on YouTube), or join social commerce platforms (e.g., Amazon). These vehicles provide an opportunity for product assessment or demonstration of the use of products. Still, a firm should keep in mind that only a small fraction of customers prepare such online product reviews and that their points of view may differ from those of more mainstream customers. This is because such deep engagement with a product presupposes some expert knowledge of the product category or product use, which the majority of the firm's clients often do not have. Moreover, there might be a bias with regard to the expressed experience with a product because the likelihood of publishing a review is higher if the product has failed in the customer's eyes or if the product delighted the customer disproportionately. Nevertheless, even though a user minority is expressing their opinions regarding specific products, those are often decisive for the purchasing behavior of the user majority. Because of this, such outlets are very interesting if the firm looks for lead users or opinion leaders and works more closely with them.

Lead users, as a particularly passionate and knowledgeable user subgroup, often go well beyond verbal, front-end NPD input, and can even offer ready-made product concepts, prototypes, or even marketable products. If these lead users do not maintain their own blogs, they can be found in expert communities, often organized as bulletin boards. This is where they present their ideas and their solutions to problems to a broader public, or where they explain how they achieved certain functionality with a product. As a result, the firm can approach the most interesting users with the best ideas or those showing the highest level of technical understanding in the firm's domain.

In a similar vein, opinion leaders, namely those users who help boost the adoption of a product during launch, can be selected and approached. Unlike lead users, they are usually not the best technical experts, but they are the people with high activity levels and a huge base of friends or followers on social media platforms, such as blogs, Facebook, or Twitter. The wider public eagerly follows their suggestions because it values their opinions.

As already mentioned, an Internet-capable PC and a search engine provide a good starting point for listening to online customer conversations. An employee merely searches for keywords, and subsequently, counts and classifies them. In such a way, it is possible, for example, to detect trendy topics and follow their developments—from megatrends, such as healthy lifestyles, to the box office sales of upcoming movies. The findings of research studies reveal that just looking at Tweets—text messages on Twitter with a maximum length of 140 characters—can not only help estimate box office sales of upcoming movies, but also video game sales and election results can be predicted with high accuracy (The Economist, 2011).

Ready-made monitoring tools for social media provide a more sophisticated, quantitative approach to follow online customer conversations. Simple analyses are available free of charge from, for example, blogsearch.google.com and search.twitter.com. More advanced solutions like the Salesforce Marketing Cloud of the Social Media Marketing Suite are not free (www.salesforcemarketingcloud.com/). They analyze, for example, each Tweet or Facebook message and relate it to the respective company by keywords and URLs mentioned. Basic information sourced in this way may include how often a firm or its products are mentioned within social media channels, how many different people are talking about a firm or its products and who they are in terms of geography or demographics. Social media monitoring tools can also tell different users apart and thus, they can help identify lead users or opinion leaders. Specifically, such tools can identify users talking regularly about particular products or product categories and who, additionally, have a huge follower base on Twitter or many friends on Facebook. Even more advanced tools can actually understand the quality of Tweets or Facebook postings with regard to such aspects as, for example, technical expertise.

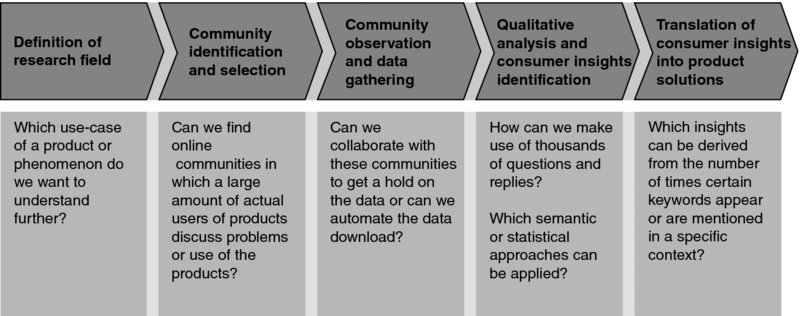

Finally, netnography is a novel methodology helping to handle the vast amount of available online information that has potential for application in NPD. Netnography is a linguistic blend of Internet and ethnography, utilizing adapted ethnographic research techniques to enable researchers to deeply immerse in online consumer conversations (Bilgram, Bartl, and Biel, 2011; Kozinets, 2002). Netnography is, therefore, a more structured, systematic, and highly (but not entirely) automated process that enables consumer statement selection, extraction, analysis, and aggregation (see Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1: Overview of the Netnography Process

Source: Adapted from Bilgram et al. (2011)

A good example is the German skin care corporation, Beiersdorf, owner of the well-known Nivea brand, which gained in-depth insights from social media in the process of developing a new antiperspirant called “Black & White” by applying netnography (Bilgram et al., 2011). This constituted a major paradigm shift for Nivea, because end consumers have not traditionally been partners in its innovation activities. Nivea's Deodorant and Antiperspirant Division converted to the netnography approach at the very beginning of the NPD process. At that time, the Division's research team had already identified the problem of stains from deodorant bothering some customers. However, the team still needed assurance from a customer standpoint about whether this problem was encountered by a sufficiently large market segment to justify the development effort. Moreover, netnography was regarded as an option to holistically get to know the consumer's universe of needs and wishes. It was also deemed suitable to filter out some of the first, potential solutions to the problems of stains that were offered in online communities by deodorant users.

The research team started by compiling search fields, topics, keywords, and related markets as well as potential sources of online information. At first, a very broad range of more than 200 social media sites in three languages (German, English, and Portuguese) were screened. They encompassed sites on cosmetics, health, lifestyle, fashion, sports, and do-it-yourself activities. Discussion threads around topics such as bodybuilding and wedding preparation also were taken into account. With the help of quantitative and qualitative selection criteria, such as community size and quality, the most relevant communities were identified and observed more carefully. Next, entire consumer discussion threads were extracted to be screened and systematically analyzed with the help of software tools.

The research team uncovered several in-depth topic clusters focusing, for instance, on stain type, the causes of staining, and the removal of stains. Numerous deodorant users described, in great detail, the problems they encountered with existing products and also offered ready-made solutions to overcome them or prevent them altogether. At this stage, the challenge was to extract the relevant pieces of information—the true “gold nuggets”—and to aggregate them.

In the final step of the netnography process, product designers joined the research team to help make sense from the findings and translate them into new product ideas, which, in turn, would enter the subsequent testing and development stages. The netnography results also helped convince Nivea's management that the project was worth pursuing and was not aiming at just a niche market. The number and (geographical) extent of complaints regarding deodorant stains was used as a proxy to judge if the NPD team had identified a real problem that would translate in market demand when solved. Netnography helped Nivea understand its customers' needs better, thus allowing the company to create a truly unique selling proposition, i.e., a stainless antiperspirant differentiating itself from other offerings, which mainly concentrated on communicating their protection period. The Black & White deodorant turned out to be Nivea's most successful product introduction ever, and netnography became a standard NPD tool, complementing classic market research techniques.

KEY BENEFITS FOR NPD THROUGH LEVEL 1 SOCIAL MEDIA IMPLEMENTATION:

- A great deal of content available for free or with minimum investment

- Fertile ground for selecting specific customers to provide deeper NPD insights or launch support

- A source of unbiased customer opinions due to unobtrusive observation

Level 2: Dialogue with Customers

Beyond listening “incognito” to customer conversations on different social media platforms, firms can enter these discussions more actively and disclose their identity. Thus, employees of a firm can join user discussions and offer solutions to problems experienced with existing products or they can ask questions to identify the core of the problems with the product. Firms can choose to interact with customers on third-party, virtual platforms or on their own platforms.

Several benefits are attributed to third-party platforms. First, they are often well known and attract a large number of users, so that, from day one, a great deal of interaction with real customers is possible. In particular, it is very hard to reproduce expert communities (e.g., about cooking, pets, extreme sports, or home improvement) where firms can get in touch with people who are lead users or opinion leaders because each platform has its own lock-in mechanism. For instance, very active community members have often reached a certain rank within the community and might be reluctant to switch to another platform and leave their status behind. Second, third-party platforms are somehow a neutral territory that a firm might want to use to contact competitors' customers or people who do not use a certain product category at all.

Although many reasons speak in favor of interacting on an existing, third-party platform, this strategy is not always risk-free. On such a platform, a firm never has the same amount of control as on a proprietary one. It depends upon the goodwill of the owners and maintainers of the platform. If a discussion goes wrong, or the firm's account gets hijacked, it might not be able to react in time, before the topic spreads to a wider audience. In addition, the way the firm interacts, the solutions it proposes, or the ideas it shares with these independent communities are visible for nearly everybody—including the competition.

If the firm takes the time and invests in its own platform, it can circumvent many of these risks. It also can build a closed user circle or offer an invitation-based membership. However, the main challenge is that the community has to stay interesting for its members, otherwise it will soon be deserted, and one day, may even die away. Maintaining a vital community requires firm commitment and employees must be given the responsibility for its management.

Obviously, not all third-party platforms are alike. Some allow less, some more control. If a firm, for example, decides to build up its own profile on Facebook for a brand or a product, it is able to control the posts and comments there. Further, Facebook is a platform that engages users in many ways. A firm that maintains its virtual presence there is not solely responsible for keeping the network alive. Posts by friends and other firms will keep the single user occupied. In addition, many firms already have Facebook profiles with many friends and followers that they have built up for marketing purposes, and these can also be tapped for NPD activities. In particular, users can be contacted that have indicated their interest and affection by “liking” the firm's Facebook page. In this way, the firm can specify, very precisely, who it would like to target or to invite to join its NPD initiatives, based on, for example, demographic criteria.

An example of a company that leveraged existing social networking sites is Del Monte's Pet Food Division (Crawford and di Benedetto, 2011). It went through all the steps previously described. It searched social media platforms and listened to what pet owners talked about. It analyzed thousands of blog entries, forum posts, and replies. This way, it was able to identify the biggest concerns of pet owners. Further, it was able to identify a new customer segment, characterized by the self-conception that “Dogs are people, too!”

Del Monte's management decided to address the need of this segment with a new offering, because their needs differed greatly from the needs of existing customers and this was matched by an adequate willingness to pay. From listening to pet owners online, accompanied by data mining and analysis, Del Monte's NPD team was able to identify opinion leaders of their newly detected customer segment. The team built an invitation-only community, approached about 500 pet owners to join this community, and finally encouraged them to participate in developing a new product tailored to their expectations.

It is important to note that they did not only rely on a handful of customers with very specific needs, but approached as many as 500 people. By engaging this relatively large group, del Monte avoided a potential over-customization of the product to individual demands that did not necessarily mirror the broader market.

The result was a new product called “Snausages Breakfast Bites,” which del Monte launched in half of the normal time and with huge success. These are dog treats in the shape of bacon strips and sunny-side-up eggs flavored accordingly and containing an extra dose of vitamins and minerals. Both the specific flavors and the nutritional benefits were important to the pet owners approached. In particular, when asked what they most wanted to feed their dogs in the morning the majority agreed it was something with a bacon-and-egg taste.

In a similar vein, the Internet giant Google used Twitter and the Google+ social network to start its “Google Glass Explorer Program” in spring 2013 (Financial Times, 2013). Interested users—the only limitation being a U.S. resident and willingness to pay $1,500 upon selection—could apply via these online channels for a Google Glass before a nationwide product launch planned for spring 2014. This group, consisting of early adopters, lead users, brand ambassadors, and fans (a potential choice criterion being, for instance, the number of followers on Twitter of the respective person) was asked to provide specific product/prototype feedback. In a later step, the group members were asked to invite further product testers/users. Altogether, beyond receiving valuable product feedback and suggestions for additional features, Google stirred up a certain buzz for its innovative product in the target market. It may also be possible to leverage this group in the future, for example, to develop apps for the Google Glass's small screen.

KEY BENEFITS TO NPD FROM THE IMPLEMENTATION OF LEVEL 2:

- Direct, reciprocal exchange with different customers

- Piggybacking on existing, popular online platforms

- Relatively modest investment

Level 3: Integration of Customers

Existing platforms, such as blogs, discussion boards, or forums, can limit the firm's interaction with its customers because they might be confined to text usage only while restricting the upload of images or additional data. They also tend to lack any customized tools supporting the customer while creating a design or a configuration. Further, they make it difficult for the firm to actually use the gathered data. Thus, considering an even deeper engagement with social media for NPD purposes, i.e., Level 3, can be an option to overcome such challenges.

First and foremost, the firm can approach the customer by means of tried-and-tested market research techniques (e.g., conjoint analysis, factor analysis, overall similarities approach) embedded in social media applications. Customers can be asked, for instance, to compare certain products available on the market or to rank them in order of certain product features. With a lot of customers within reach, the company will be able to test a huge amount of possible configurations using reliable data.

Second, different sweepstakes and quizzes provide interesting options to integrate customer input in NPD in an entertaining way. The firm can mix the content of the sweepstake or quiz in such a way as to alternate between the entertainment and the issues it really wants to understand. For example, the firm can find out if the customer knows the key characteristics of the products, by determining if the customer is able to match products with the right applications, and if his most important criteria when he buys the product match the product itself.

Third, toolkits are a helpful medium to lower the entrance barrier for customers and yield more applicable NPD input for the firm. These are virtual, computer-aided tools allowing customers to develop their own products or at least to customize the design of existing products. For instance, if a car manufacturer asks a customer to hand in the configuration of his preferred sports car, the customer may have serious difficulties describing it with only text and images, unless he is an expert in the field of automotive design. But if the firm provides him with a virtual toolkit, although it may, at first glance, limit his creative freedom, it will definitely help him configure a car from parts that exist and work together. Thus if the user, for example, chooses a certain chassis, he can only select from a certain range of tires. In addition, the firm can also avoid designs in which the car has unusual/useless parts like wings or an anchor chain.

Toolkits can also be applied for idea, design, or solution contests. In these contests, a firm not only asks for ideas, but may also leverage the many social media users to evaluate and comment on these ideas. Word of mouth spreads quickly—sometimes even exponentially—in the virtual world; if one community member participates in a contest, all his followers or friends likely will become aware of that. The firm, therefore, reaches out to far more people than it initially addressed. With the input of these additional participants, the creator of the idea may refine his original idea, and others, inspired by it, can add their own ideas. Finally, the virtual community can preselect and rank the submitted ideas.

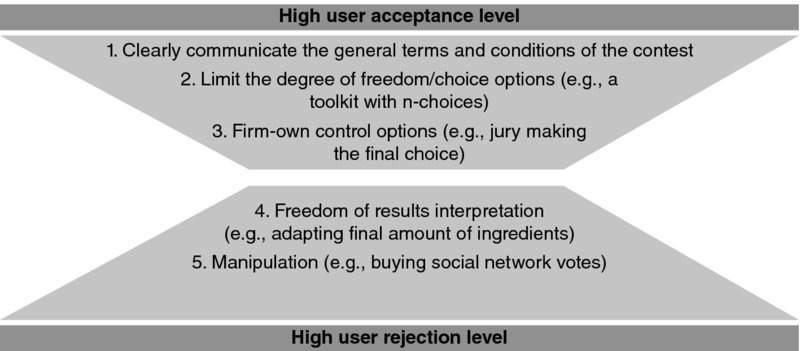

However, as a word of caution, the “best” idea will not necessarily get the majority of the votes. Recurring examples show that people have a tendency to vote for odd or bizarre ideas, because they find it amusing that the respective firm would have to implement them. Further, the most active Facebook users with the biggest follower and friend bases are not necessarily the people with the best technical knowledge, highest creativity, or highest intention to buy the final product. A “safety net” is therefore recommended to avoid situations in which the idea with the most votes automatically becomes the contest winner (Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.2: Recommendations to Manage Idea, Design, or Solution Contests Embedded in Social Media Applications

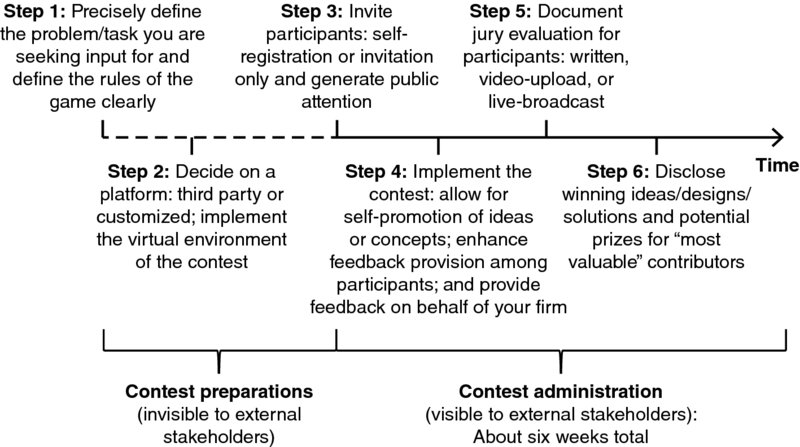

The reasons people take part in such contests are manifold. First, they may have a need to tell the firm what kind of product or solution would satisfy them (e.g., lead user). Second, they may be very creative or have a sophisticated technical expertise and just want to show off. Finally, they might just be loyal customers who want to help their favorite firm. However, as the firm asks its customers to invest time and to give away a potentially good idea, it may want to offer something in exchange. Many firms allot a prize for the contest winner, in order to boost participation. Figure 3.3 provides a blueprint for such a contest.

Figure 3.3: Exemplary Outline for an Idea, Design, or Solution Contest

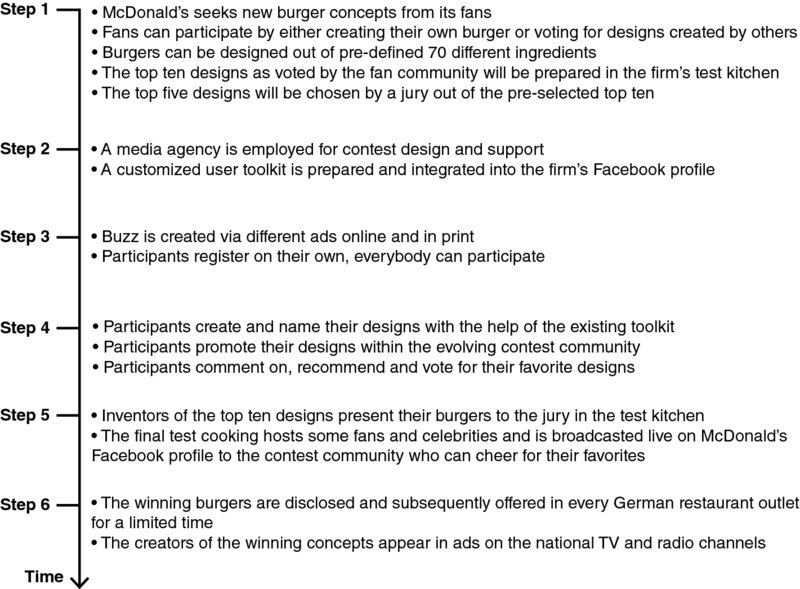

Several examples illustrate successful applications of various contests and toolkits for NPD purposes via social media. For instance, in 2013, McDonald's German subsidiary ran its highly acclaimed Facebook campaign “MyBurger” for the third time in a row, attracting about 150,000 participants and yielding more than 200,000 burger designs in three different categories: classic, veggie, and snack. The winning burgers went on sale as a special offer for several weeks in all German McDonald's outlets but were not put on the regular menu. McDonald's in Germany regularly extends its standard menu with temporary offerings, which however, are created by in-house food designers, not customers. The MyBurger initiative—lasting about six weeks (a four-week submission window and roughly two weeks of trial cooking and jury deliberations) was a huge success for the restaurant chain. Right from its start in 2011, it generated the highest number of first-time customers ever, record sales, and the highest number of burgers ever sold during a McDonald's campaign. MyBurger allowed customers to design their favorite burger, mobilize supporters, test the prototype, and finally act as the burger's testimonial if it was chosen for countrywide sale (see Figure 3.4). To facilitate customers' participation and guarantee the feasibility of the resulting burger designs, McDonald's applied a toolkit for co-creation by the users.

Figure 3.4: Steps of McDonald's MyBurger Contest

Note: Compiled from publicly available sources like McDonald's German homepage for illustrative purposes. No claim for completeness of mentioned activities.

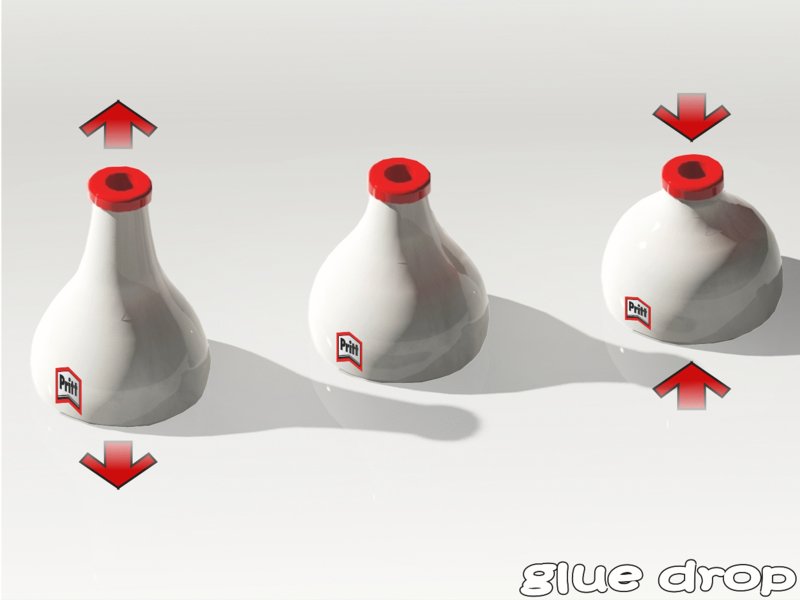

In a similar vein, in 2011, Henkel, a German FMCG giant, set out to look for innovative packaging solutions for their well-known consumer adhesive tapes, correction, and fixing products, and launched a solution contest for its Pritt brand. In particular, the classic “Pritt stick”—the world's first glue stick consisting of solid adhesive in a twistable casing—has something of an iconic status in German home, school, and office environments. In general, packaging for consumer adhesives needs to ensure protection during transportation, but must also facilitate their straightforward use. While the existing Pritt packaging design undoubtedly met both criteria, Henkel's NPD team still wanted to tap users' creativity and explore the need for a potential packaging redesign. Moreover, Henkel wanted to gain experience in the systematic involvement of users, in order to achieve better and faster innovation. As a result, the “Adhesive Packaging Design Contest” (accessible via their www.packdesign-contest.com website and connected to Henkel's Facebook and Twitter sites) targeting designers worldwide was launched with the help of HYVE, a German innovation service firm. In a few steps, the design proposals could be uploaded and all users who registered for the contest had the opportunity to comment on these designs. Packaging developers from Henkel also contributed to the exchange of ideas. Within a submission period of six weeks, more than 1000 participants from 20 countries came up with over 380 design ideas encompassing a broad spectrum of text and drawings. Additionally, more than 7000 evaluations were made, 3400 comments were given, and 2900 messages were sent to Henkel. A jury composed of experts from academia and the Henkel packaging design team evaluated the submitted ideas and concepts. They were assessed according to five criteria: attractiveness of design, sustainability, innovativeness, user benefits, and efficiency. The winning design, “Glue drop”—submitted by a participant from El Salvador—was particularly impressive because of its ease of use and great “fun factor” (see Figures 3.5 and 3.6). The winner was awarded  3000 (∼US$4000). In addition, a special award consisting of an iPad and a Henkel goodie bag was given to the two most valuable participants of the contest who consistently made outstanding contributions and exhibited above-average fairness.

3000 (∼US$4000). In addition, a special award consisting of an iPad and a Henkel goodie bag was given to the two most valuable participants of the contest who consistently made outstanding contributions and exhibited above-average fairness.

Figure 3.5: Henkel's Print Design Contest

Source: Henkel

Figure 3.6: Winner of the Henkel's Packaging Contest

Source: Henkel

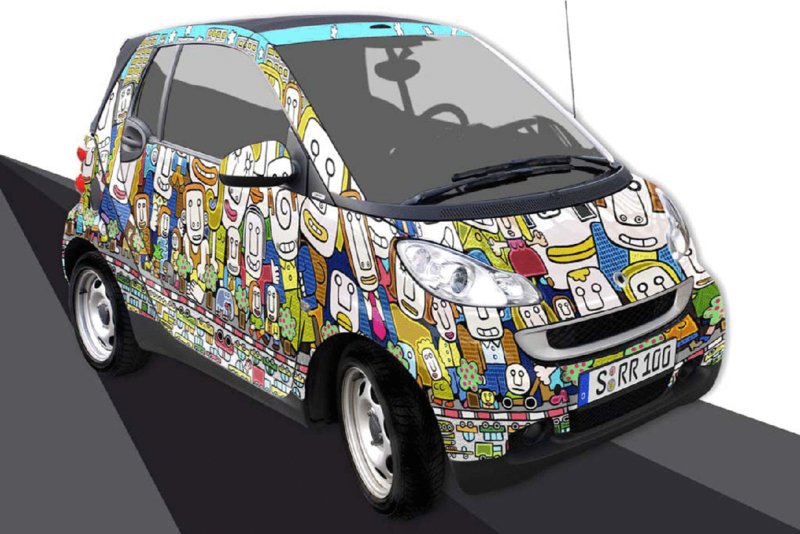

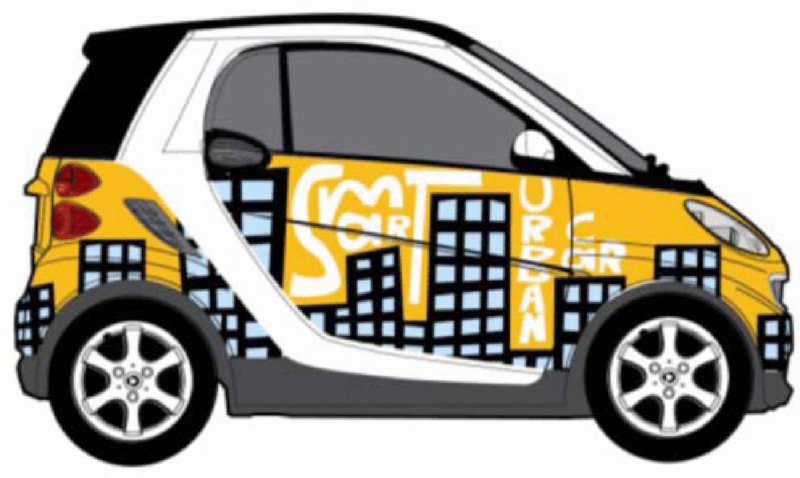

Finally, in 2010 the car manufacturer Daimler launched its design contest for the exterior of their Smart car. It was open for participation for about six weeks. To implement this contest, Daimler adopted a dedicated platform that was loosely connected to Facebook. On the proprietary platform, the participant could create his own account. Roughly 10,000 people did so. These people were attracted through traditional advertising.

In the next step, the user could download a template showing the front, the back, and the left-hand and right-hand side of a Smart car. As a community member, the user was able to create one or more designs based on this template. Other users could rate these designs and comment on them. One could also advertise their own design easily by promoting and sharing it on Facebook. In total, over 50,000 designs were created and over 600,000 evaluations were submitted. Additionally, 15,000 direct messages between participants were sent and about 30,000 comments were made about specific designs. Thus, on average, every design received 12 votes and every designer received about 3 comments on his work. The designs with the most votes were evaluated by a jury during the Geneva Motor Show, and the jury picked the winners (see Figure 3.7).

(a)

(b)

(c)

Figure 3.7: Winning Designs in the Smart Design Contest (a) First Prize, (b) Second Prize, and (c) Third Prize

Source: Smart Design Contest powered by Hyve (www.smart-design-contest.com/)

In addition to prizes for winning the contest [first place  1500 (∼US$2000) to third place

1500 (∼US$2000) to third place  750 (∼US$1000)] there were also prizes for activity on the platform [first place

750 (∼US$1000)] there were also prizes for activity on the platform [first place  800 (∼US$1000) to third place

800 (∼US$1000) to third place  300 (∼US$400)]. Over and above monetary incentives, Daimler ensured that the winners received a great deal of publicity and exposure. Daimler issued an official press release regarding the results and the winners of this contest that has been taken up by several newspapers.

300 (∼US$400)]. Over and above monetary incentives, Daimler ensured that the winners received a great deal of publicity and exposure. Daimler issued an official press release regarding the results and the winners of this contest that has been taken up by several newspapers.

KEY BENEFITS TO NPD THROUGH IMPLEMENTATION OF LEVEL 3:

- More precise exchange with customers on predefined topics

- Gathered data is proprietary, easily understandable, and directly accessible

- Great influence on and control of the events taking place on the respective platform

Table 3.2 summarizes the extent to which firms can use social media applications and tools for NPD input.

Table 3.2 Three Levels of Social Media Involvement in NPD

| Level 1

“Listening to Customers” |

Level2

“Dialogue with Customers” |

Level 3

“Integration of Customers” |

|

| Ownership | Low | Medium | High |

| Social media categories |

|

|

|

| Platform types |

|

|

|

| Tools |

|

|

|

| Main actors | Mass end user, lead user, opinion leader, functional expert, non-user | ||

| Incentives for actors | None | Monetary, non-monetary | Monetary, non-monetary |

| Evaluation | |||

|

Very low | Neutral | Very high |

|

Very low | High | Very high |

|

Very high | High | Verv low |

|

Very high | High | Verv low |

| NPD stage** |  |

|

|

| Example | Nivea “Black & White” deodorant | Del Monte “Snausages Breakfast Bites”; Google Glass | Henkel “Pritt stick” adhesive; McDonald's, “MyBurger” campaign; Smart car |

Note: *Feasible only if the platform is expandable and allows customization of content. **Different shades of gray indicate the appropriateness of engaging in a certain level of social media use in a particular NPD stage.

Benefits and Risks

Many firms in the FMCG sector are starting to use social media for their NPD endeavors. Clearly, Facebook and Twitter are the most popular transmitters between the virtual, networked (mass) customer and the firm, although they differ significantly with regard to the amount of information transferred. Online communities and blogs are a fertile ground for finding lead users, and these are helpful in obtaining more specific NPD input. More firms seem to apply social media toward the end of their NPD process, seeking rather superficial adaptations of their marketing mix or hoping to create awareness for their new product in online networks during its launch. There seem to be very few firms that actively use social media from the very start of their NPD process.

Using social media in NPD can yield many benefits. The first advantage is the ability to get in touch with those (end) customers who are not the “usual suspects,” i.e., are not those who have a good relationship with the company's sales force or who are already known to the firm due to participation in past promotional competitions or games. Moreover, users who are customers of competitors or nonusers of a certain product category can be approached relatively easily because they all can be found on the most popular platforms. The sheer volume of potential customers and the diversity of their backgrounds cannot be ignored. Finally, contact with customers via social media is very direct and not filtered by any market research intermediaries.

However, there are also some challenges in using social media, which should not be underestimated. Being rather new tools, their use is not completely risk free. Not all customers approaching a company via social media have good intentions. Firms face “hijacking” of their social media initiatives on a regular basis, be it ridiculous ideas submitted to a contest or ungrounded hostility. This is aggravated by the fact that news can spread virally in online surroundings, and is very hard to control. Such incidents may harm the firm's brand and make it difficult to virtually collaborate with customers in the future. Further, peer feedback—one of the basic premises of social media—might not always exert a beneficial impact on new products that are designed by users. Initial studies, with both real and artificial NPD projects, demonstrate that users seeking feedback to their product ideas/designs from friends in social networks tend to strip off many additional features from the designed product and curb their creativity (Hildebrand et al., 2013). As a result, the firm loses profits and receives less creative input. Instead of getting numerous individual suggestions and designs appreciated by the participating individual, the firm receives numerous watered down proposals representing the smallest common denominator of what the participating individual and all his friends could agree on. To make things worse, the customer himself is unhappy with the final result because it mirrors the preferences of his friends and not his own and he might even feel forced into submitting it. Finally, the usual challenges of integrating customers into firm-owned NPD activities can be transferred to the social media context as well. First, many social media users are likely to have difficulty properly articulating their needs and may lack sufficient knowledge to offer solutions to their problems. Second, numerous users may come up with only marginal product changes.

3.5 Success Factors

As our examples have shown, while it can be worthwhile for FMCG firms to integrate customers through social media channels into their NPD activities, it is not a straightforward undertaking. Two sets of success factors can be identified: internal and external.

Internal Success Factors

First, a firm should set clear goals for customer engagement in NPD activities via social media and regularly monitor them. Irrespective of how “cool” it might be to utilize social media for NPD or related activities, it cannot be an end in itself. Firms should consider what the added value of integrating consumers is, and whether this added value is worth the effort and cost associated with it. Before inviting consumers to participate in NPD, firms ought to clarify for themselves whether and why they want to use social media and how exactly this can contribute to NPD success. Often firms invest significantly in social media platforms with very little understanding of how exactly this will support their goals. In fact, it remains very difficult to assess the impact of social media on NPD outcomes or the financial success of the firm. Therefore, as a first step, a firm might find it helpful to define internal criteria for measuring results before customers are engaged through social media.

Second, firms should realistically manage the expectations of their own NPD team regarding the quality of user input. Reaching out to a huge customer base via social media where customers can contribute easily will invariably lead to hundreds if not thousands of ideas. Likely not all of them will be of good quality, but there might be very good ones among them. Trying to identify these is a major challenge.

Third, it may be helpful to define in advance when and where to integrate customers. Some firms may start as early as the ideation stage, while others might do it for the first time in the development or launch stage. In more mature stages, the NPD team may look for prototype testers or opinion leaders who support product diffusion. It is equally important to think through the whole campaign and clearly define who makes decisions at which stage. Is this the majority of the customers or the company itself? It can also be helpful to think of the worst possible outcome, set up participation rules accordingly, and make sure to have an exit strategy at hand (see also options to manage idea, design, or solution contests).

Finally, it is essential to clarify intellectual property rights upfront, before customers participate. If this is not done, customers providing valuable contributions may feel betrayed if they do not participate in the successful outcomes of their involvement.

External Success Factors

First and foremost, it is important for the firm to exhibit maximum transparency in interacting with the virtual customer. This means clear communication of the rules of cooperation in advance (see also options to manage idea, design, or solution contests). For instance, it must be made clear whether the number of votes counts or if a jury finally chooses the competition winner. Similarly, the competition should have a clear timeline. A time frame of a few weeks—the exemplary firms in our chapter opted for a six-week period of customer interaction—is best, as it allows both the customer to stay interested and the firm to manage its customers' involvement easily. The composition of the jury and the qualifications of its members should also be made clear. It might be helpful to make a picture or a video showing the jury discussing its verdict.

Second, if the firm wants to boost participation, it should make sure that an employee or a communications agency responds quickly to user inquiries or comments.

Third, if the firm decides to work only with a selected group of users, they should be carefully picked to boost input quality and limit the probability of disclosure to the broader public/competition. In some cases it might be helpful to sign nondisclosure agreements with key customers.

Finally, if a firm is looking for good contributions, it should describe the problems for which it seeks solutions precisely. Providing customers with toolkits also helps them to make meaningful contributions.

3.6 Conclusion

Changing the firm's R&D paradigm and opening up its innovation processes for customer input can lead to better innovation output. In order to achieve it, however, the firm should learn how to manage its NPD-related customer interface. Social media as a relatively new societal phenomenon are gaining increased attention from managers responsible for NPD activities and may become a valuable tool for catching the VoC. In particular, the exponential growth of social networks, online communities, and blogs in the last decade makes it attractive for firms to tap these vast, international user groups to seek their expertise and input into certain NPD activities. However, irrespective of their potential attractiveness, it is anything but a trivial task for firms to successfully integrate social media into their NPD on a regular basis. To help firms make better use of social media in NPD, our chapter sketched three levels of the integration of social media into NPD, starting with a rather nonbinding option based on passive observation, followed by a second level based on a more active involvement on foreign virtual territory, and finally the third level using proactively designed tools on proprietary platforms. The chapter additionally provided an overview of the success factors for the use of social media in NPD, which can be helpful as a starting point for firms considering first or deeper engagement in this domain.

References

- Bartl, M., J. Füller, H. Mühlbacher, and H. Ernst, 2012, A Manager's Perspective on Virtual Customer Integration for New Product Development, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 29(6): 1031–1046.

- Bilgram, V., M. Bartl, and S. Biel, 2011, Getting Closer to the Consumer: How Nivea Co-Creates New Products, Marketing Review St. Gallen, 28(1): 34–40.

- Crawford, M., and A. Di Benedetto, 2011, New Products Management. 10th edition, New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Financial Times, 2013, Google Accelerates Glass Rollout. October 28. Available at www.cnbc.com/id/101149814.

- Griffin, A., 2013, Obtaining Customer Needs for Product Development. In K. Kahn, S. E. Kay, G. Gibson, and S. Urban (Eds.), PDMA Handbook of New Product Development, 3d Edition, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 213–230.

- Gruner, K. E., and C. Homburg, 2000, Does Customer Interaction Enhance New Product Success?, Journal of Business Research, 49(1): 1–14.

- Hildebrand, C., G. Häubl, A. Herrmann, and J. R. Landwehr, 2013, Conformity and the Crowd, Harvard Business Review, 91(4): 23–24.

- Hoffman, D. L., T. P. Novak, and R. Stein, 2012, Flourishing Independents or Languishing Interdependents: Two Paths from Self-Construal to Identification with Social Media. Working Paper. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1990584.

- Kozinets, R.V., 2002, The Field Behind the Screen: Using Netnography for Marketing Research in Online Communities, Journal of Marketing Research, 39(1): 61–72.

- Markham, S. K., and H. Lee, 2013, Product Development and Management Association's 2012 Comparative Performance Assessment Study, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 30(3): 408–429.

- The Economist, 2011, Can Twitter Predict the Future? June 2. Available at www.economist.com/node/18750604.

- Tuten, T. L., and M. R. Solomon, 2013, Social Media Marketing. Boston: Pearson.

- Verhoef, P. C., S.F.M. Beckers, and J. van Doorn, 2013. Understand the Perils of Co-Creation, Harvard Business Review, 91(9): 28.

- Wilcox, K., and A. Stephen, 2013, Are Close Friends the Enemy? Online Social Networks, Self-Esteem, and Self-Control. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(1): 90–103.

About the Contributors

- Dr. Anna Dubiel is the Roechling Assistant Professor of International Innovation Management at the WHU, Otto Beisheim School of Management, Vallendar, Germany. She received her PhD from the WHU, Otto Beisheim School of Management. Her research interests include the internationalization of new product development and R&D. Contact: anna.dubiel@whu.edu.

- Dr. Tim Oliver Brexendorf is an Assistant Professor of Consumer Goods Marketing and Head of the Henkel Center for Consumer Goods (HCCG) at the WHU, Otto Beisheim School of Management, Germany. He earned his PhD at the University St. Gallen, Switzerland. Prior to his academic career, he worked in management consultancy and for several international retailers. He is Co-Editor-in-Chief of the Journal of Brand Management. His research interests include brand and product innovation management. Contact: tim.brexendorf@whu.edu.

- Dr. Sebastian Glöckner is a PhD student at the Chair of Technology and Innovation Management, WHU, Otto Beisheim School of Management, Vallendar, Germany. His research interests focus on the role of the sales force in NPD.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of Dr. Michael Bartl, CEO, Hyve AG; Dr. Stefan Biel, Senior R&D Manager Foresight & Innovation, Beiersdorf AG; and Dr. Nils Daecke, Corporate Vice President Digital Marketing Beauty Care, Henkel AG & Co. KGaA. Further, we would also like to thank the editors of this volume for their valuable feedback.