5

CATALYZING TACIT KNOWLEDGE EXCHANGE WITH VISUAL THINKING TECHNIQUES TO ACHIEVE PRODUCTIVE OPEN INNOVATION COLLABORATIONS

Karen A. Kreutz

Iluminov, LLC

Kim D. Benz

Iluminov, LLC

5.1 Introduction

Tacit knowledge exchange (TKE) within Open Innovation (OI) teams and between their stakeholders is a critical factor for ultimate joint value creation success. The role of TKE is acknowledged to be critically essential to breakthrough innovation. As stated in Koen and colleagues' 2004 article, “Breakthrough innovations involve the sharing of tacit knowledge among individuals. However, this type of knowledge . . . is inherently fragile. . . . Conceptually, the speed of tacit knowledge exchange depends on the degree that the environment is collaborative.” One dimension of the collaborative environment, the article explains, is that there is trust between the person sharing tacit knowledge and the receiver of that knowledge.

The topic of tacit knowledge is not widely discussed in circles beyond cognitive scientists—even though the majority of what we ourselves know is considered tacit. The definition of tacit knowledge suggests its exchange occurs in a social context. For Open Innovation teams, ensuring a trust-based environment is essential for TKE.

A simple analogy will help illustrate the crucial role of TKE in innovation teams. Consider the task of baking a cake from scratch. A recipe is very useful to indicate the steps one takes and the ingredients needed. For Open Innovation efforts, this is equivalent to project management level and business process operational systems. Other tools like bowls, measuring cups, and spoons are used to combine the ingredients into a batter. For innovation within organizations, this is similar to following best practices. Those approaches, while necessary and helpful, only go so far. Heat, provided by the oven (trust-based environment), is needed in order to transform the blended ingredients into the final product, the delicious cake. The heat for innovation teams is Tacit Knowledge Exchange. Visual thinking (VT) methodologies can be compared to the oven and can greatly assist in “releasing” and channeling this heat from the group of individuals brought together in these experiences.

There are two interrelated challenges that commonly hamper TKE: (1) transforming individual expertise to collective understanding and (2) generating trust. Visual thinking methodologies assist teams in overcoming these challenges by fostering team-level learning and innovation progress. These experiences contribute to strengthening the teams' climate of trust.

The topics presented in this chapter are addressed to those leaders and/or stakeholders of OI teams who are seeking to increase the probability of a successful outcome of their mutual endeavor. Their focus will be on the why and how to employ VT during the phase of Open Innovation when the combined team actually needs to collaboratively innovate to deliver the desired good or service to the market.

When it was initially developed, VT was used to address social and business challenges and in academia, to promote learning and creativity. This relatively young field of practice has not reached the tipping point of adoption in broader industry, business, or in product development. The appeal of VT techniques is that they take little effort to begin and they yield benefits immediately. These techniques readily adapt to specific team needs throughout the innovation process and are easily integrated into the team's operations. Expertise to apply the tools can be in-sourced from an array of skilled practitioners or developed in-house.

This chapter seeks to elucidate how tacit knowledge can be harnessed expeditiously to catalyze its exchange as the basis for a productive collaboration in OI teams.

5.2 Visual Thinking Introduction

Visual Thinking: An Overview

For the purpose of this chapter, VT refers to a suite of practices that are cutting-edge for catalyzing effective tacit knowledge exchange within Open Innovation teams. All visual thinking methodologies employ the power of visual language and visual listening. The output is always the combination of words and graphics to capture and organize important information.

VT approaches go beyond the common “verbal only” communication (whether oral or written) in their ability to increase participation, contribution, and engagement; promote collective understanding; and foster authentic alignment. The mere experience offered by a VT technique creates a sufficiently safe environment in which individuals are willing and able to share what they know and are more open to consider information from others. The entire team can now benefit from the knowledge of the different individual experts.

In all VT modalities, the revealed bits of knowledge are captured and organized within graphics. The output provides a framework to reveal the “bigger picture” along with the details. This type of output expedites assimilation of new knowledge by each participant. A collective group understanding emerges with greater ease. The net effects are:

- Accelerated individual learning by each person exposed to the output

- Progress toward collective understanding by all

- A more harmonious pathway to alignment on tasks/next steps and the approach to use

- Organized and documented information available to support robust decision making

- Creation of an archive of the team's cumulative learning

These techniques are particularly useful when diverse subject matter experts are gathered to solve a problem or collaborate. This is naturally the case in Open Innovation endeavors. The tacit knowledge exchange generates a collective understanding from which solutions emerge. Thus, with effective TKE the innovation learning work is better able to proceed as fast as possible while minimizing risk and while avoiding rework and other inefficiencies. A direct outcome is that alignment occurs more harmoniously among team members and between the team and its stakeholders. On top of that, effective TKE contributes to a climate of trust in the OI team's culture, spurring motivated and engaged action by individual team members.

Two Branches of Visual Thinking

Through visual thinking methodologies, an array of diverse thinking and viewpoints is made coherent by a structured process that may be messy at times, but reliably delivers results.

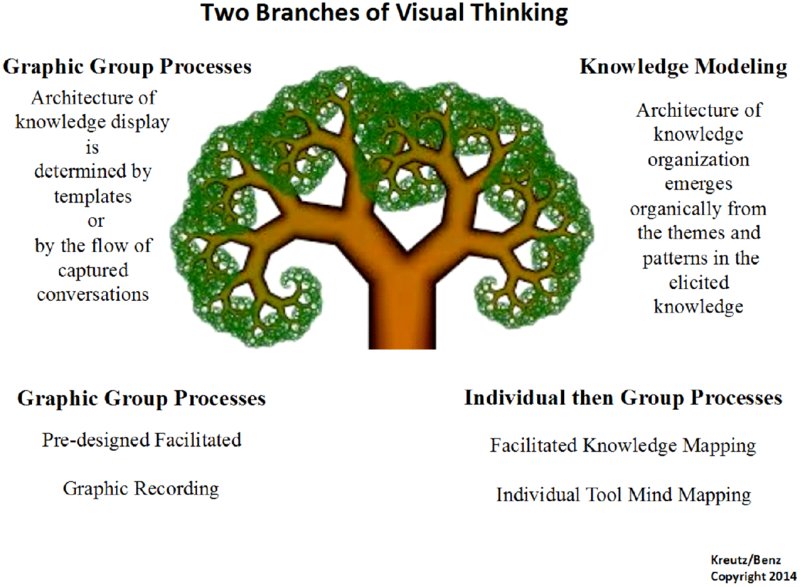

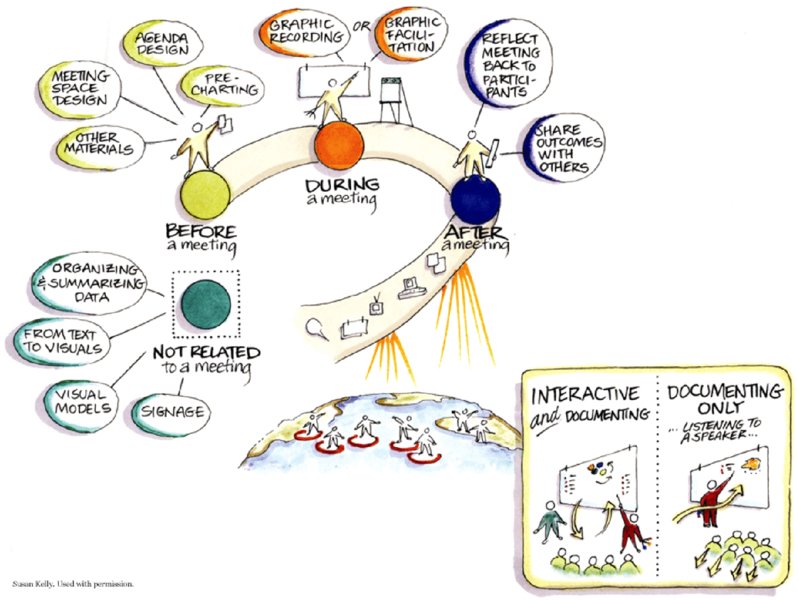

There are two main branches of VT: Graphic Group Processes and Knowledge Modeling. Figure 5.1 provides an overview of both branches.

Figure 5.1: Visual Thinking Overview

Branch 1: Graphic Group Processes

There are two subclasses of this branch of visual thinking. The first pertains to an expertly facilitated session that is predesigned for the team to achieve an objective. A series of graphic templates guides the collection of knowledge and produces the desired outcomes. The second variant involves leveraging a skilled graphic facilitator to record, in real time, a conversation about an important topic to yield an output that merges graphics and words.

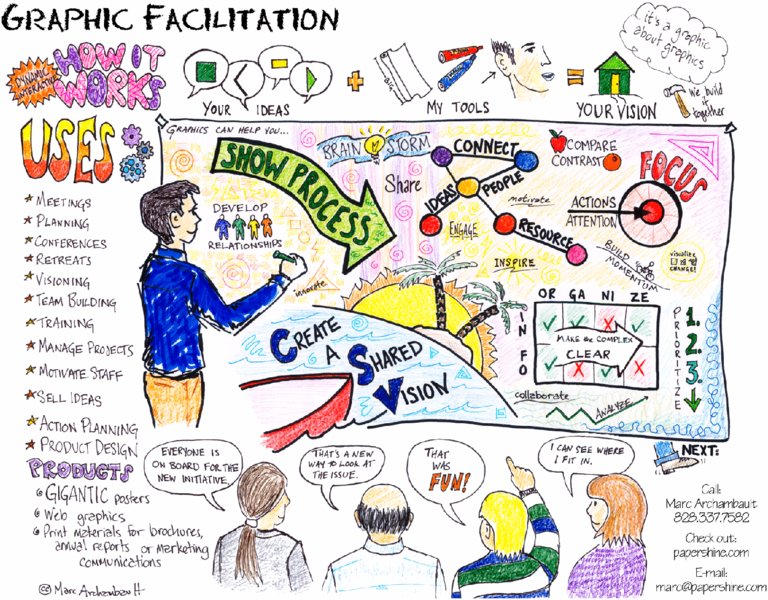

Figure 5.2 illustrates how the use of colored markers and paper (blank or template) can create a depiction of a group process that in turn can communicate the information to others. By reviewing this graphic, one can learn how both types of graphic group processes work and realize their merits.

Figure 5.2: Graphic group processes overview. Graphic facilitation refers to both types of graphic group processes. For predesigned facilitated sessions, an experienced facilitator chooses templates to guide the conversation and display elicited knowledge. For graphic recording, a skilled recorder captures the conversation as it occurs in text and images.

Copyright © 2009 Marc Arachambault

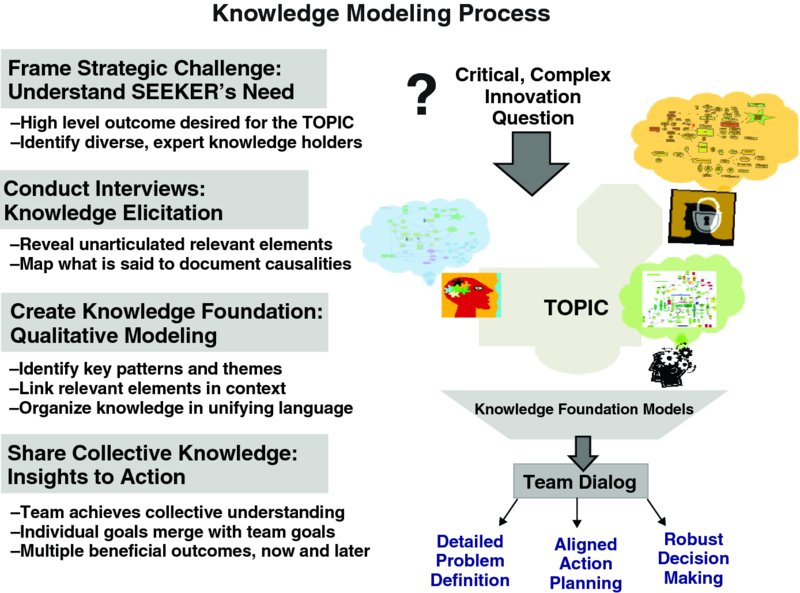

Branch 2: Knowledge Modeling

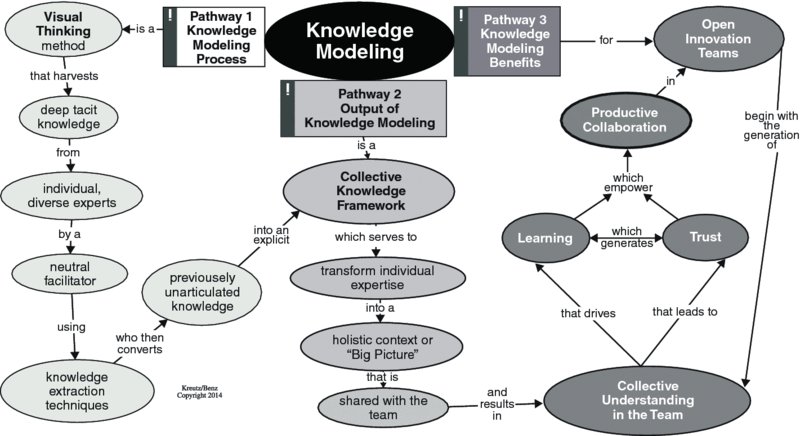

Knowledge modeling involves direct harvesting of individual knowledge. The step to harvest the individual's expert knowledge can be facilitated by an interviewer or be completed with individual mind maps. Subsequently, the information is synthesized across contributors. A unifying framework emerges from the analysis. The relevant information is then organized into that unifying framework. The output is an explicit collective knowledge foundation that is then shared with the team. The conversations that ensue establish new meaning and a collective understanding emerges. Figure 5.3 displays a model of knowledge modeling as a visual thinking method and its benefits for Open Innovation teams.

Figure 5.3: Knowledge Modeling

Visual Thinking: Background

The need to incorporate visual thinking in how we work and collaborate has never been greater. We live in a world filled with uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity. NPD and innovation, per se, are wrought with uncertainty and risks. The technical problems that need answers are becoming more complex, requiring more specialized, diverse expertise to solve. The way forward for innovation teams is often ambiguous; there are many opinions about the best next steps toward an ultimate goal. There are strong pushes globally throughout industrial and social systems for “better, faster, cheaper innovation,” and for higher overall productivity.

Additionally, we live in the midst of the Information Age. As humans, our ability to absorb the massive amounts of available information and to make sense of it has fallen behind the demand to do so. As a stress response, people tend to seek to simplify and resist externally imposed change. Due to corporate downsizing, there are often fewer people to actually do the innovation work. This adds to the stresses experienced with in-house innovation teams. There are noticeable trends pointing to the fact that employees feel like they have less time for meaningful conversations (like the kind that are critical for quality TKE!) because taking action is expected. These stresses are then augmented with the new challenges associated with being part of an Open Innovation team.

The use of graphics to foster group communication, creativity, and collaboration has become popularized by the recent increase in publication of books aimed at audiences beyond Silicon Valley and the fields of education and design. Namely the business and thus innovation communities are starting to take notice. (See the References section at the end of this chapter for a sampling of publications and resources.)

New approaches are needed to reduce the time, effort, and stress associated with tacit knowledge exchange if innovation efforts—especially Open Innovation collaborations—are to be productive and successful. Visual thinking offers new approaches that easily “plug into” existing operations that both assist teams to function productively and help individuals to thrive with lower stress.

How Visual Thinking Is Different

VT methodologies differ from other means to address an innovation team's collaboration performance in two key ways.

- VT does not require individual team members to have mastery in communication skills.

Some trainings focus on building the individual's communication (listening, inquiry, advocacy, etc.) and interpersonal skills. While these trainings are necessary and can have impact in the longer term, they do require effort and motivation by the individuals themselves to learn and master. VT is a facilitated process and therefore offers a more neutral way to communicate (share and receive information) compensating for the skill levels of the participants. VT's graphic group processes use a template, e.g., a SWOT (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, threats) matrix. These templates provide focus for the conversation and serve as a record of what was said for all to see. In VT's knowledge modeling processes, the information from expert individuals is synthesized and then transferred into organizing frameworks. This helps democratize the knowledge held in the team. Both VT experiences result in nearly effortless sharing and enhanced learning.

- VT does not require the team to take time off from innovation work.

The use of VT is not the same as a training that requires work to stop. In fact, VT is leveraged within necessary team activities and helps the team get real work done. This happens despite the current state of team dynamics. In VT's graphic group processes, knowledge is elicited and shared in real time. The gathered and organized information is archived for immediate or future use. In VT's knowledge modeling processes, the harvesting of the needed individual expertise happens “offline” in a manner that does not disrupt ongoing work. The group who is seeking the information is briefly gathered. Once the organized collective knowledge is shared, the team comes to a new and more holistic common understanding. Active, constructive dialogue instantly ensues on the topic at hand.

Benefits of Visual Thinking

VISUAL THINKING METHODOLOGIES ARE EFFECTIVE AND EFFICIENT BECAUSE THEY:

- Create a safe social setting as context for sharing and receiving knowledge

- Evoke tacit knowledge while providing acknowledgment to the contributor

- Integrate members' different information to reduce complexity

- Can be right-sized for the purpose

- Produce organized representations that help create and document group understanding

- Complement other OI practice frameworks and operational best practices

Taken together these benefits support both transforming individual expertise to collective understanding that drives team learning and generating a trust-based collaboration.

5.3 Visual Thinking and Open Innovation Endeavors

Open Innovation and NPD

All innovation projects go through the familiar new product development lifecycle phases; that is, they pass from Discovery (Front End of Innovation) through Development to Commercialization (Launch and Implementation). Open Innovation represents efforts to collaboratively innovate with a partner with the aim of joint value creation.

One characteristic of OI is that it can be leveraged at any phase of the NPD lifecycle or throughout its entirety. In fact, the NPD phase of the specific project provides the context for the specific Open Innovation endeavor.

Within Open Innovation endeavors, interestingly, one party typically represents What Is Needed? (customer need, technical challenge, market opportunity) while the other brings What Is Possible? (technologies, new capabilities, specialized resources, etc.). As with NPD, there is an overarching business process that is followed when pursuing Open Innovation. OI success requires that the parties achieve excellence in both OI phases of this process: Getting Together and then Working Together.

- Getting Together excellence is about finding this match between parties to form the best domain, or scope, of their collaboration. The Getting Together experience and output provide the foundation for the actual innovation work. The process of Getting Together includes three distinct steps:

- Strategy: Making the decision whether or not to pursue an Open Innovation arrangement for a given business—What Is Needed? Key management leads this and ties the decision to strategic business goals.

- Seek: Finding and vetting a potential partner who represents What Is Possible? to help meet that business What Is Needed?

- Business Model: Negotiating the associated business/innovation model agreement.

- Working Together is about conducting the innovation activities to deliver the output to the market. Excellence during Working Together involves efficiently combining the best understanding at any point in time of What Is Needed? and of What Is Possible? in order to develop the solutions to create the final output. The process of Working Together consists of one step:

- Deliver: Assembling a joint, multifunctional team that develops its operational systems and collaborates until the delivery of the good or service is completed.

For the purpose of introducing visual thinking techniques, the focus will be on the activities within the Deliver phase of the OI process.

Joint Innovation Success and Tacit Knowledge Exchange

Both of the TKE challenges are ubiquitous within a single firm's innovation efforts. These same challenges are exacerbated when companies seek to expand their new product development innovation capacity via Open Innovation. This is largely due to the effect of melding two organizational cultures.

During the Working Together phase of OI, people with diverse skills and functional expertise are asked to create a new blended culture as they make innovation progress. This team, however, has been asked to innovate. Innovation is difficult enough without the added burden of establishing new behavioral norms, a common language, and operational systems.

Yet for the work of innovation to proceed, the timely and efficient exchange of unarticulated, or tacit, knowledge is required. Unhindered access to expertise about the need and possibilities from each party's knowledge holders is imperative for optimal solutions to the task at hand to emerge. Joint innovation success, therefore, necessitates that all of the best, combined expertise is leveraged when it is needed. However, the normal mechanism of exchanging tacit knowledge is not guaranteed to be quick or complete. This is why a proactive intervention to catalyze TKE should be considered for Open Innovation teams.

The tacit, or unarticulated, knowledge exchange process first involves exposing the knowledge about a given problem from diverse, relevant expert knowledge holders. Next, this elicited knowledge from each individual needs to be shared in a manner that is understandable by others. Then, other collaborators must assimilate the knowledge. Only at this point can a true collective understanding emerge. When this is consistently achieved, the team has demonstrated the ability to transcend the first TKE challenge.

At the start of Working Together in an Open Innovation team, the requisite trust to facilitate the free and effective exchange of tacit knowledge has not yet been established. Reaching a sufficient level of interpersonal trust can take considerable time—a luxury few teams have. The effort required to build this type of trust is due to the complex social nature of the organizational context that yields the team's culture. Encouragingly, the generation of trust can be positively influenced by proactively catalyzing TKE via Visual Thinking.

Thus, the ultimate basis for joint innovation success in OI endeavors is whether or not the team is able to readily and simultaneously overcome the two TKE challenges.

How Visual Thinking Supports Productive Collaboration

Productive collaboration is one in which a team maximizes the value creation potential of the project while minimizing any efficiency losses. Insufficient interpersonal trust, especially in the blended culture of OI teams, can lead to withholding of information, intentionally or not. To achieve productive collaboration, the team must overcome a “Catch-22” associated with TKE. Namely, a person in a team will more readily share their own tacit knowledge with other team members when they trust the other team members. Yet, a person tends to trust other individuals after the others have shared deeper knowledge with them. If this paradox is not resolved, productive collaboration will be stymied.

VT methods address this paradox by fostering tacit knowledge sharing and receiving, whatever the current level of trust. Because tacit knowledge is exchanged, trust increases. The tacit knowledge released via VT actually helps fuel a virtuous cycle of transforming individual expertise to collective understanding and generating trust. All leaders who wish to have productive open innovation teams will now begin to see that targeted use of VT methods can help ignite this virtuous cycle sooner rather than later.

Advantageously Directing VT to Drive Innovation

The work at the very heart of the innovation process involves identifying a problem or knowledge gap, conducting a series of experiments to learn about solutions and then making decisions about moving forward. This cyclical process is recognizable to anyone who is familiar with innovation. Within each phase of the NPD lifecycle, these iterative learning cycles solve the problems that occur as the idea for the new good or service is translated into the form that will be brought to market. To conduct each of these learning cycles, an OI team needs to repeatedly define tasks and make decisions.

Many factors affect a team's productivity. One such factor is how expeditiously a team reaches authentic alignment when defining tasks for action. Another key factor is how efficient the team is at making robust decisions. How teams function with regard to these activity elements is especially critical when there is a strong demand for stakeholder alignment or when projects face high technical uncertainty. If either the team's ability to define the tasks of innovation or to make solid decisions is compromised, inefficiencies emerge. Rework, missed opportunities, and lost time undermine innovation's progress and productivity.

Every innovation team has to design how they will determine the tasks the team will undertake and how they will make decisions. Each of these activities depends on thorough and efficient TKE if the team seeks productive collaboration.

- Tasks: How well the team figures out the best action plan depends on its ability to collectively understand what is known at a given point in time with regard to the business need/problem and the possibilities for addressing it. Also, the degree to which the team members and its stakeholders are truly aligned on a given way forward is critical to maximizing speed of progress.

- Decisions: How well a team brings together all salient knowledge as the basis for making an informed decision affects the level of risk associated with that decision. The speed to get to a robust decision is directly related to making this knowledge part of the collective understanding.

Defining tasks and making decisions represent high leverage points for proactive use of visual thinking to overcome the TKE challenges. These two activities also directly contribute to the degree to which trust can be generated as an attribute of the OI team's culture. If there is less than authentic alignment about the tasks or if decisions prove to be less than robust, distrust emerges. By addressing any misalignment of opinions, leaders can facilitate the harvesting of the deep expert knowledge to foster learning and collective understanding and simultaneously build trust.

5.4 Understanding the Tacit Knowledge Exchange Challenges

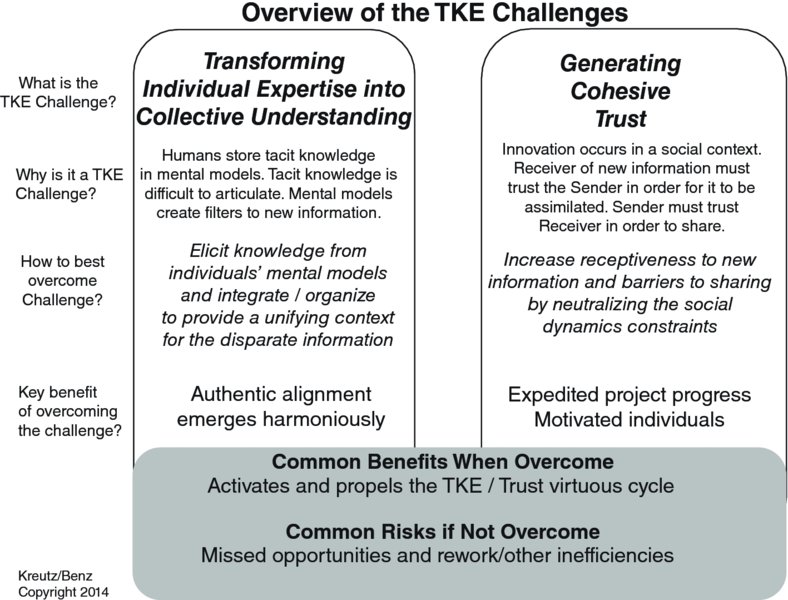

Overview of TKE Challenges (Figure 5.4)

It has already been presented that there are two TKE challenges and that TKE is important for productive collaboration in an OI context. The objectives of this section are (1) to provide a deeper understanding of the nature of these challenges, and (2) to share insights about why VT methods represent a pragmatic means to address them.

Figure 5.4: Overview of TKE Challenges

Optimizing conditions to foster TKE is a vital, yet often overlooked aspect within the complicated work of any innovation effort. One reason is the existence of a prevailing paradigm; that is, the primary way to achieve TKE is to improve interpersonal relationships and communication skills. It is indeed necessary for individuals to strengthen these skills for the general purpose of becoming collaborative innovators. However, these skills alone are insufficient to enable the OI team to deftly overcome the two TKE challenges.

Tacit Knowledge Exchange Challenges: Causes and Insights

The two key tacit knowledge exchange challenges arise due to the very nature of innovation itself: Innovation is a human activity that occurs as a heuristic process in a social context.

An examination of this statement reveals the cause of challenges associated with TKE and provides insights about how VT helps overcome them.

Innovation Is a Human Activity

“Real learning gets to the heart of what it means to be human” (Senge, 2006, p. 13). Since the innovative NPD process is really a sequence of learning cycles, it is necessary to look more closely at how individuals learn.

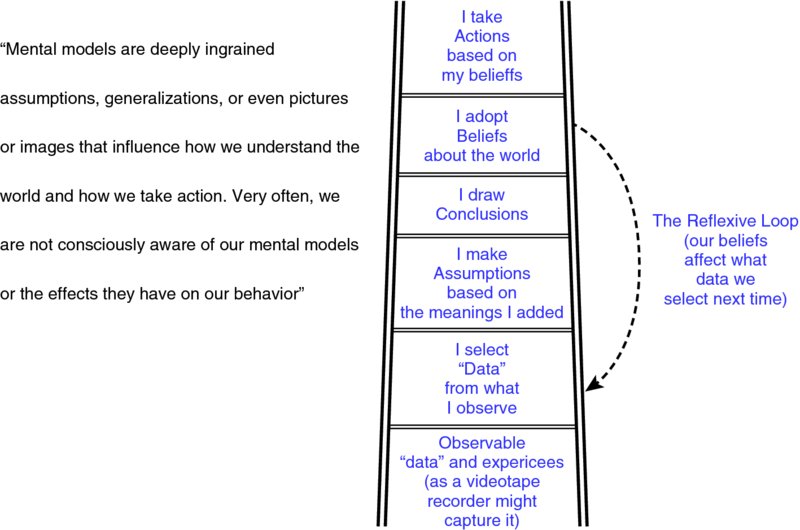

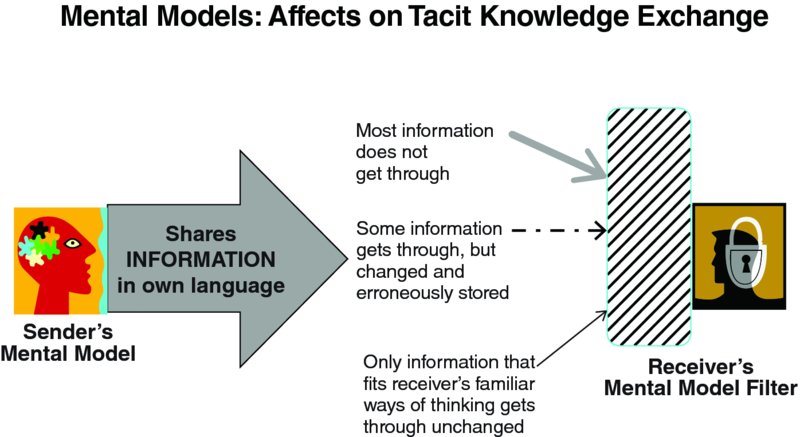

Humans store their cumulative knowledge, mostly tacit, in complex mental models. These models are basically the repositories for personal mastery. There is a paradox associated with mental models. On one hand, innovation teams benefit by leveraging the expertise from each person's mental model in order to articulate the need-based requirements and create solutions to the problems. On the other hand, mental models are likely to be detrimental to a person's ability to share knowledge in a manner conducive to others understanding it, and to learn from others given that their own mental models filter new information.

Innovation Occurs as a Heuristic Process

Innovation work is a heuristic process that requires individuals to work collaboratively to explore how problems can be solved (Figure 5.5). Heuristics are know-how strategies used by experts based on their experience. They are also referred to as “rules of thumb” and “educated guesses.” They allow individuals to decide how to approach a new problem based on what they have experienced in the past. Heuristics are basically short cuts to eliminate the need to research everything exhaustively.

Figure 5.5: Senge's Ladder of Inference

Senge, P. The Fifth Discipline, p. 8, 2006, Double Day Publishers

Figure 5.6: Mental Model: Effects on Tacit Knowledge Exchange

If innovation were an algorithmic process, it could be structured into steps and codified so that it could be repeated again and again with similar results. Most manufacturing processes are good examples of the application of algorithms. Within the work of innovation, however, team members and other important knowledge holders use their know-how expertise when they apply their heuristics to establish hypotheses for solutions and propose the experiments to determine if those are valid. Thus, as humans, the team members rely on mental models to both exploit what they know and they apply heuristics as they figure out how to solve problems.

OI teams need to effectively achieve alignment on what they need to learn while considering all the relevant points of view on how to move forward. If teams do not achieve authentic, collective understanding–based alignment as a basis for confidently defining the tasks, it is likely that rework and other inefficiencies will undermine their productivity. After the experimentation, the team needs to make decisions based on the results and conclusions. Only if these decisions are made with consideration of all pertinent information and full alignment will risks be minimized.

Innovation Occurs in a Social Context

An individual does not conduct the work of innovation. Rather, it happens in groups of individuals with each bringing a critical expertise to the table. Most Open Innovation collaborations of major importance require teams who are truly interdependent on each other in order to achieve the desired outcome. This interdependence necessitates collaboration. The social dimension of innovation refers to the collaboration between diverse subject matter experts that is necessary for considering all the salient dimensions of the problems and relevant solution elements as the effort moves through the NPD process. These social interactions with others, often from multiple disciplines or functions and, as in Open Innovation, different companies, are an unavoidable component of the innovation process.

Let's take a closer look at what is actually going on socially within any Open Innovation team as they form and begin the Working Together phase. A review of widely applied Team Performance Models (such as Cog's Ladder) reveals that there are two processes occurring in parallel. One involves the dynamics associated with the social nature of the interpersonal interactions. The other parallel process involves the all-essential tacit knowledge exchange. Achieving the status of High Performance Teams is a virtual guarantee for achieving productive collaboration.

The social nature brings interpersonal relationships and interaction dynamics (which will initially tend to conform to the norms of each person's home organization) to the forefront. Add to this dynamic the aspects that individual diversity including personality style, communication skills, and ethnic/country culture factors bring. Generally speaking, these social dynamics tend to trump the more fragile, trust-dependent tacit knowledge exchange process. These social phenomena hinder, if not prevent, innovation teams from reaping the benefits of attaining “high performance” status. Without sufficient TKE to bolster the growth of trust, the trust dimension of the OI team's culture can stagnate.

In order to encourage the requisite trust basis to emerge, an OI team's TKE needs to happen effectively and efficiently in spite of the invisible presence of an often counterproductive initial team culture.

TKE Challenge 1: Transforming Individual Expertise to Collective Understanding

Due to the reliance of the innovation process on individual mental models and the use of heuristics, it is now apparent why the first TKE key challenge emerges.

Open Innovation efforts are staffed with subject matter and functional experts from each firm in a previously agreed manner. Being human, the brains of these experts have built mental models of how they view the world and organize what they know. These individual mental models provide a rich reservoir of expertise and knowledge known as technical mastery. Effective interpersonal tacit knowledge exchanges and smooth application of heuristics in order to solve problems, define tasks, and make decisions are required from the start in order to achieve productive collaboration. Members of the Open Innovation team or stakeholder group have their own understanding of the effort and its status and what should happen next. Convergence in a diverse team to a collective understanding is not a trivial process.

In order to consistently overcome this TKE challenge, OI teams must continuously assess how to best harvest the tacit knowledge/heuristics from the optimal combination of individual experts. They then need to convert the relevant information into a format that integrates the disparate yet relevant knowledge. Finally, activities are needed until a collective understanding among the broader Open Innovation team (beyond the relevant experts) and its stakeholders is realized.

The learning and thinking of all participants rises to a new level just by participating in a VT experience. This is because the human brain is wired to process visual information. Another aspect of visual thinking is that it generally helps “unravel and clarify situations in a way that reduces complexity” (Craig, 2007, p. 11). Organization of the shared information reveals the context of the information and its connectedness, making it easier to grasp and remember.

When this TKE challenge is conquered, conversations ensue. Harmonious and authentic alignment then provides the foundation for defining the next tasks or for making robust decisions.

TKE Challenge 2: Generating Trust

This second core challenge to TKE is linkable to the fact that any innovation process occurs in a social context (Fonseca, 2002).

Innovation solutions emerge from networks of conversations among people operating with sufficient trust. All innovation efforts progress, over time, through conversations with and among people with differing knowledge and skills sets. In the case of Open Innovation, these conversations need to occur within teams blended from different organizations and they usually need to occur before sufficient trust has been established.

Without the requisite trust, TKE is thwarted. One aspect of this challenge is that the real impediments to TKE in the social arena are relatively “invisible” to those involved given that the barriers emerge, for the most part, subconsciously (Senge, 2006).

Without sufficient trust among team members, information shared, which does not exactly “fit” with another's mental model, is likely to be rejected. The receiver of the new information must trust the sender enough before an effort is made to explore and seek to understand this information. Once clarified, the receivers can learn and subsequently integrate the nugget to expand their mental model. This social challenge to sharing/acquiring knowledge is a real issue preventing productive collaboration because it is only in the minds of the diverse team members that learning occurs and solution ideas emerge.

As discussed, effective sharing of information so that it is received and learned by another is not straightforward. Additionally, if individual learning is hindered, it can become rate-limiting for innovation progress. The existence of mental models and reliance on heuristics often cause individuals and subsequently teams to remain at superficial levels. Thus, in the absence of trust they avoid the effort and investment required for effective listening and understanding of each other and any new information. The net effect is that, without intervention, teams tend to bypass the complex realties of today's innovation challenges and to undermine the goal of productive successful innovation.

Overcoming the Generating Trust TKE challenge is somewhat tricky given that it is a cultural context in which trust emerges or does not emerge. Influencing the culture of a team involves many aspects unrelated to knowledge exchange. However, there are a couple of aspects of the team's operational design that can contribute to accelerating the generation of trust as a cultural attribute if TKE is promoted. These are: (1) defining the problem to be addressed, (2) agreeing on how to address it, and (3) deciding what the results mean.

With regard to the TKE challenge of Generating Trust, visual thinking offers two benefits. First, it provides an opportunity for individuals to participate and engage with each other in a rather safe social setting. Interactions among the participants become a fun way to spend time together while doing real work toward a common objective. Second, the output democratizes everyone's knowledge. This feature enables each to learn from the others rather effortlessly and establishes a foundation for further sharing.

5.5 Using Visual Thinking in OI Teams

As previously mentioned, there are two branches of visual thinking—graphic group processes and knowledge modeling. Each represents an array of tools, techniques, and approaches to catalyze TKE. They are particularly useful for the important strategic activities of defining tasks, clarifying technical problems, and making complex decisions. These scenarios illustrate how VT can contribute to productive collaboration in Open Innovation teams.

Graphic Group Processes

Graphic group processes enable easy gathering of information from a broad group, including those outside the direct OI team if desired. These processes document the elicited information with visuals and text, enabling teams and stakeholders to reach understanding and then alignment on a particular topic. At a high level, these methods all occur with a group of people who are together for the experience. This experience can be a one-time meeting or a multiday event. While these methods have been pioneered with participants in the same physical location, digital and web-based tools and processes are emerging. All of the graphic group process methods need only simple tools (sharpies/markers, sticky notes, blank paper, or easy-to-use predesigned templates). The methods are customizable to the purpose and importance of the specific event.

It is relatively simple to get started with exploring the use of graphic group processes with your OI team. There are several books that can expedite the use of this branch of VT included in the references listed at the end of this chapter.

Graphic Recording

Graphic recording is used when a team wishes to capture important information in a visual display for the purpose of empowering action. Such instances include creating a project vision, depicting the history or context of a situation, or capturing the best practices for a given activity. It is often used to capture the essence of an important speech or strategy conversation.

In this subtype of visual thinking, a skilled graphic recorder develops a pictorial representation of the team's discussion as it occurs. The recorder can either help facilitate the conversation while recording or simply record the conversation. Usually no templates are used, just large sheets of blank paper and markers. There are graphic recording professionals who can be hired for a modest fee. For those interested, this is a skill that can be learned; books and trainings on the topic are available. (See the References section at the end of the chapter.)

The benefit of this specific technique is that the group can focus on having its conversation. The dialogue is much more active given that individuals tend to respond to what is visually captured, sparking the release of more information. The graphic facilitator in the room also ensures that those attending are enrolled in the conversation. The digital image of the final set of graphics becomes a record of the session for the participants. This output can be used to bring nonparticipants on board quickly following the session.

Predesigned Facilitation Processes

These processes involve a facilitator who first works with a team representative to define the objectives and outcomes desired for the session. The discussion segments are then planned to achieve this objective and deliver the outcome. During the event, the group facilitator leads invited participants through a series of discussions and enables the capture of what is said on selected graphic templates (Figure 5.7).

Figure 5.7: Description of the Graphic Recording Process

Copyright © Susan Kelly. Reproduced with permission.

The facilitator can be someone on the team or not; it is imperative that the individual is not biased toward a specific outcome. No specialized skill is needed and instructional guides are available for many templates. In fact, whole kits can be purchased to accomplish certain tasks, for example, a team startup or strategic visioning. These processes can be self-guided according to a predetermined protocol, or they can be custom designed using a wide variety of templates that are available. Predesigned facilitation processes are highly vetted as a means to achieve diverse input and involvement, yet produce explicit representations of the shared information as a basis for group alignment and action planning or decision making.

With the increase in popularity of these approaches, individual consultants who are expert in predesigned facilitation processes are widely available to help customize and conduct sessions. Many offer training classes for anyone in the partnering companies or OI team who is interested in building this facilitative leadership skill. Professional facilitators are recommended for assisting complex, large, or high-stakes meetings.

Graphic Group Processes in Practice

There are many ways to leverage both types of graphic group processes within Open Innovation teams.

Scenario 1: Team Startup

When members of the OI team from the partner companies assemble to meet each other they need to establish how they want to operate in this collaboration. This is key to a newly formed OI team given that activities like decision-making processes and conflict resolution procedures need to be chosen. Stakeholders' participation is key so that they can be confident that the OI team is aiming for their intended goal and empowered for success.

Team startup exercise kits, which have been predesigned for newly formed teams to commence on the path toward high performance, are available. Using this type of session serves to ground the comingled team with common understanding of why they are there. Additionally, it helps establish a common language about the What Is Needed? and What Is Possible?, as the context for the project. The outcome includes establishing new relationships and clarification of what success looks like for the team.

Scenario 2: Determining Action Plans

Usually the people assigned for the Working Together phase of OI project are different from those who completed the Getting Together steps in the Open Innovation process. This creates a need to transfer information from the Getting Together phase to aid the Working Together team to form a shared team vision for their joint innovation work.

Once the team startup vision emerges, the associated high-level action steps are ready to be converted to more detailed plans. For OI teams, graphic facilitation group processes can be designed to include all relevant knowledge holders and functional partners so that the plans produced are actionable, efficient, and aligned with the intent of the business arrangement. Importantly, the participants can go beyond those “assigned” to the team to include key stakeholders and functional partners who will indirectly support the effort or who have specific insight from the Getting Together phase.

The Strategic Visioning™ Graphic Facilitation method is one example of a successful, proven process to help diverse teams create an aligned team-level vision. In this process the team reviews History and Context for the OI project, conducts a SPOT (Strengths/Problems/Opportunities/Threats) analysis then envisions the best future state via a Cover Story. Finally, the 5 Bold Steps template is completed; this will then serve to guide detailed action planning.

For Open Innovation teams it is especially important to have common understanding of the match between What Is Needed? and What Is Possible? that led to the companies' relationship. The Strategic Visioning™ process or its equivalent affords the team the opportunity to take a conscious step back and ask themselves, “What do we together really know about the Needs and Possibilities?” and “How do we best begin to deliver against this goal?”

Knowledge Modeling

Knowledge modeling as discussed in this chapter represents an emergent approach in the realm of visual thinking. Concept mapping is a precursor to knowledge modeling; it extends back to the work in the 1970s by J. Novak. Also relevant is the work on Mind Maps developed by Tony Buzan and others1 (see Resources section at the end of this chapter). It has been mainly applied in the field of education as a means to capture detailed knowledge revealing interrelationships. Similar to the surge of development and interest in graphic group processes, the usefulness of concept mapping for other applications became apparent. Particularly, it supports creativity in teams and the documentation of detailed, interrelated knowledge.

Knowledge Modeling: The Process

As shown in Figure 5.8, knowledge modeling starts with a dilemma that is hindering the team's progress. Usually this issue is complex and its solution necessitates that the expertise of diverse knowledge holders be revealed in greater detail.

Figure 5.8: Knowledge Modeling Process

A person designated as a knowledge integrator acts as the facilitator for this process. Once the team's need and desired successful outcomes are understood, the team's leader can identify the experts who will be interviewed. It is important that the knowledge holders have varied perspectives and expertise about the topic; that is, their knowledge casts light on the issue from distinctly different angles. The next step is the knowledge elicitation interviews. It is important that the interviewer is detached from the outcome yet proficient in the subject matter to follow what is being shared. The knowledge integrator needs to be curious and understand what is being shared so that the expert continues to engage in the sharing. The goal of the interviews is to gather the salient information from each expert's perspective while exposing the causalities between the facts. It is important to capture what is said (not what is heard and filtered through the interviewer's mental model!). This entails making an audio recording of the interview. The process continues with the creation of a unifying framework within which the related knowledge bits from all the interviews are organized and displayed. This resultant knowledge foundation serves the Open Innovation team by accelerating the understanding of the complicated details in the context of the “big picture.” In other words, it helps the team see the big picture.

The process of knowledge modeling works for teams because it makes operational what goes on in the heads of individuals with an integrated thinking ability. In his book The Opposable Mind: How Successful Leaders Win Through Integrative Thinking, Roger Martin, 2007 depicts integrative thinking as a four-step process, as he contrasts it with conventional thinking. The premise is that integrative thinkers are able to come up with “breakthrough” resolutions to perplexing dilemmas due to their ability to process complex interrelated information into a counterintuitive “architecture” as the basis for finding novel solutions. In fact, one case study he presents involves A. G. Lafely at P&G and the desire for innovation while lowering spending (two opposable ideas). This led A.G. to the strategic choice for P&G to pursue Open Innovation with its Connect+Develop(sm) business model.

Knowledge Modeling: In Practice

Scenario 1: Problem Clarification

It is often said: “A problem well stated is half solved”. Yet how often do functional experts on a team rush off to test their hypotheses before a detailed, collective understanding of the real problem is developed?

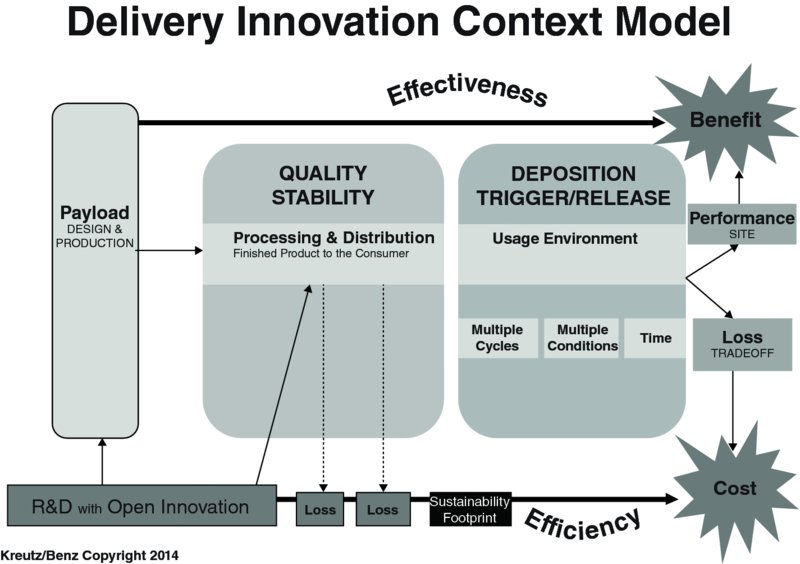

One such team was faced with a perplexing technical issue. The team was composed of diverse functional experts from two different organizations. This issue had stumped the experts for years and was causing delays in launching new products to the market. The technical transformation involved the delivery of a proprietary biological active in a product to be consumed by the users. The issue holding up the program was that the active became “deactivated” or was unstable in the formula. The team had been struggling to address the issue within the scope of manufacturing the product. The team requested that knowledge modeling be conducted to help identify new solution pathways. The interviews of diverse subject matter experts resulted in a framework for the issue that involved the entire delivery process. That is, it showed the pathway of the active from its production through to its use in the user's home. Once the knowledge from the different experts was superimposed on this framework the team very quickly realized that the origin of the problem and source of potential solutions was not in their process but in how the raw material was produced. This reframing of the problem subsequently opened up new innovation pathways to overcome the stability challenge. See Figure 5.9.

Figure 5.9: Delivery Innovation Context Model

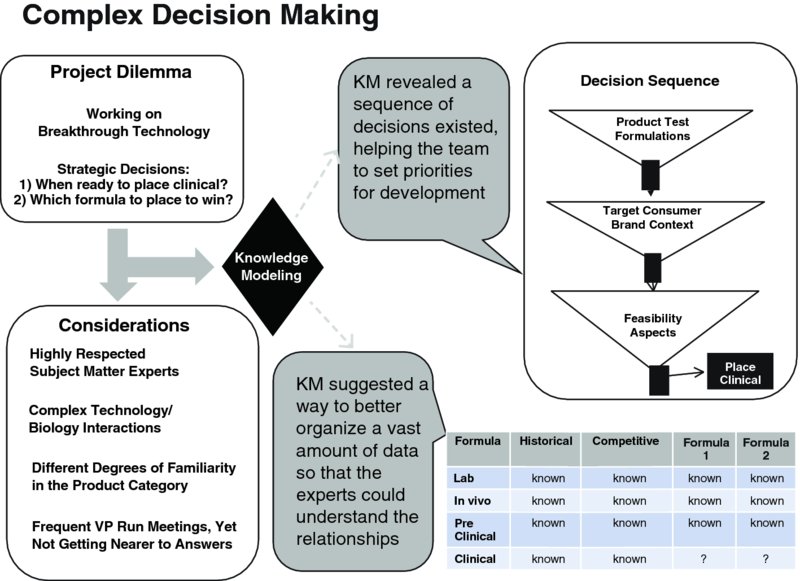

Scenario 2: Complex Decision Making

Some decisions are straightforward, but most strategic decisions made by Open Innovation teams are not. Also, decisions that deal with topics that have a high level of technical uncertainty or risk often become very complex. Often, teams delay making these decisions until more details are known.

The Vice President of an R&D organization posed two questions to the team working on the most important project in his NPD portfolio. This was a project that was to introduce a “breakthrough” technology that had the potential to change the landscape in that product's category. The product would need to undergo a clinical trial to be qualified for launch. The VP asked:

- When will the team be ready to place this clinical?

- Which products (test formula and competitive products) would be placed in the clinical?

After months the team had not replied so he called for more frequent meetings and started attending himself; he had hoped to lead them to closure on these questions. Despite this effort the answers did not emerge. The level of technical uncertainty was still very high. Multiple technical experts had very strong points of view. Deep mechanistic understanding of how the product worked and could be expected to perform in a clinical was limited to one individual.

The VP requested that knowledge modeling be leveraged to get closer to the answers. The outcome took less than one month to deliver. As far as the first question is concerned, the team discovered that there was actually a sequence of decisions to be made before the timing of the clinical could be determined. This simplified discussion of the technical issues and enabled the team to set priorities on learning. As for the second question, a matrix to organize key technical data versus prior clinical results and the associated formulae was proposed. This would put all of the quantitative data and facts on paper and be a basis for all, not just the one expert, to discuss the merits of the different test formulae. Details about the global business and business plans would then factor into which competitive product to place in the study. See Figure 5.10.

Figure 5.10: Complex Decision Making

Graphic Group Processes versus Knowledge Modeling: A Comparison

This is a high-level comparison of the two branches of visual thinking, which provides guidance as leaders consider applying such approaches in their OI team's activities. Table 5.1 lists the similarities and differences of each approach. There are a few pitfalls to be avoided as OI teams embark on applying visual thinking. Table 5.2 presents some pitfalls and possible workarounds for using visual thinking within Open Innovation teams.

Table 5.1 Similarities and Differences Between Graphic Group Processes and Knowledge Modeling

| Similarities | ||

| Function | Both serve the purpose of catalyzing tacit knowledge exchange | |

| Output | Both yield graphic representation of the shared knowledge relative to the conversation's topic | |

| Impact on Understanding | Both help individuals within the team see the details and relationships shared in the overall context. With this “bigger picture,” the team is aided in transcending TKE Challenge 1:Transforming Individual Expertise into Collective Understanding | |

| Impact on Trust | Both result in individuals sharing knowledge in a socially safe manner and publically acknowledge each expert's knowledge. This democratization of knowledge helps the team transcend TKE Challenge 2: Generating Trust | |

| Differences | ||

| Graphic Group Processes | Knowledge Modeling | |

| When to use | For gathering diverse input and when seeking alignment | To help the team reduce the complexity and risk associated with an issue or decision |

| How tacit knowledge is obtained | In a group setting with facilitated conversations guided by templates or a skilled graphic recorder | One-on-one interviews of subject matter experts or via individual mind maps |

| How knowledge is organized and presented | Knowledge is captured on a series of templates | Knowledge from the experts is analyzed; then a holistic contextual framework presents synthesized knowledge |

Table 5.2 Pitfalls in Using VT Methods in OI Teams

| Graphic Group Processes | Pitfall | Tips to Consider |

| Planning | ||

| Lack of clear objective | Work with appropriate team members to fine tune the objective. | |

| Insufficient pre-alignment with stakeholders | Ensure the inputs of stakeholders are considered so that the session can be designed to yield an output that will be accepted and implemented. | |

| Execution | ||

| Mismatch of facilitator skill relative to the topic and group dynamics. This can go either way: expert facilitator for small task and novice facilitator for a difficult task. | The one way to avoid this is to start small (small tasks and simple templates) while a novice facilitator is learning. Alternatively, for bigger team events, hire a skilled facilitator to assist with design and execution of the session. | |

| Suboptimal attendees: this can be too few, too many, or missing expertise. | Carefully select those invited to participate. Be sure to consider those outside the assigned OI team to include stakeholders and functional partners from the home organization, if appropriate for the objective. | |

| Knowledge Modeling | Pitfalls | Tips to Consider |

| Planning | ||

| Lack of clarity on defining what successful resolution of the issue looks like. | Make sure that the issue facing the team is clearly articulated and what outcome would be most helpful. Usually this takes a few iterations getting input from stakeholders and leaders. This clarity is critical to guide which knowledge to extract. | |

| Suboptimal choice of expert knowledge holders to participate | Having diverse expert perspectives is more important than quantity. Keep in mind the expertise needed may be outside of the assigned OI team and reside in the home organizations or beyond either company. | |

| Execution | ||

| Interviews/mind maps do not sufficiently uncover the interrelationships in the shared knowledge. | Skills to conduct targeted knowledge extraction interviews require practice and should be rehearsed before working with the team. | |

| Knowledge synthesis is not completed objectively or is too superficial. | Ensure that the person or small group acting as knowledge integrators is unbiased. Also make sure they have proven synthetic analytical skills to process complex data. |

5.6 Conclusions

Achieving successful joint value creation in Open Innovation endeavors depends upon the collaboration being productive. Tacit knowledge exchange (TKE) is of vital importance to the process of innovation collaboration. There are two interrelated challenges that commonly hamper TKE: (1) transforming individual expertise to collective understanding, and (2) generating trust. Without sufficient or timely TKE, innovation progress is thwarted.

The promise of productive collaborations awaits those teams that consistently transcend these two TKE challenges. However, it is more challenging to achieve effective TKE in Open Innovation teams given the additional complications associated with the blending of different cultures. The mental models of the individuals on the team, shaped in part by the culture of their original organization, create filters that impede the sharing and receiving of tacit knowledge. Additionally, a low level of initial trust hinders collaboration within the OI team.

Importantly, an interdependent “Catch-22” relationship exists between TKE and trust. Namely, a person in a team will more readily share their own tacit knowledge with other team members when they trust the other team members. Yet, a person tends to trust other individuals only after the others have shared deeper knowledge with them. If this paradox is not resolved, productive collaboration will be stymied.

Pragmatic tools to address this dilemma in a systemic manner are just emerging. Visual thinking (VT) offers a range of novel approaches that do not require individuals to be masters of verbal communication skills or the team to stop working. A practical way to begin with VT is to focus on team activities to:

- Define and align on the tasks of innovation work

and/or

- Make robust decisions in the face of complexity or uncertainty.

Individuals on the team or from the home organizations can learn enough to begin from a plethora of resources. Alternatively, OI teams can hire VT professionals to help them apply these tools.

Visual Thinking can be particularly powerful for OI teams because they simultaneously support overcoming the TKE challenges. Visual thinking methodologies are effective and efficient because they

- Create a safe social setting as context for sharing and receiving knowledge

- Evoke tacit knowledge while providing acknowledgment to the contributor

- Integrate members' different information to reduce complexity

- Produce organized representations that help create and document group understanding

- Can be right-sized for the purpose

- Complement other OI practice frameworks and operational best practices

Taken together these benefits of using VT to catalyze TKE support both needs of transforming individual expertise to collective understanding and generating a trust-based collaboration as a means to fuel productive OI collaborations.

Resources

- AHHA!, http://experienceahha.com

- Atze von der Ploeg, Pythagoras Tree on Wikipedia Commons, used in Figure 5.1

- CMAP software, http://ftp.ihmc.us

- The GROVE International Consultants, http://store.grove.com/site/index.html

- Ideaconnect, http://store.beideaconnect.com

- Inspiration software, www.inspiration.com/Inspiration

- International Forum of Visual Practitioners, http://ifvpcommunity.ning.com

- Mindjet Software, www.mindjet.com

- Joseph D. Novak: http://cmap.ihmc.us/publications/researchpapers/theorycmaps/theoryunderlyingconceptmaps.htm

- Occasions by Design, susankellylistens@earthlink.net, used in Figure 5.7

- Papershine, Marc Archambault, marc@papershine.com, used in Figure 5.2

- Tony Buzan, www.tonybuzan.com/about/mind-mapping/

References

- Brown, S., 2014, The Doodle Revolution: Unlock the Power to Think Differently, New York: Penguin Portfolio.

- Craig, M., PhD, 2007, Thinking Visually: Business Applications of 14 Core Diagrams, London: Thompson Learning.

- Fonseca, J., 2002, Complexity and Innovation in Organizations, New York: Routledge.

- Hanna, D. P., 1988, Designing Organizations for High Performance, New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc.

- Koen, P., R. McDermott, R. Olsen, and C. Prather, 2004, Enhancing Organizational Knowledge Creation for Breakthrough Innovation: Tools and Techniques, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Margulies, N., and C. Valenza, 2007, Visual Thinking: Tools for Mapping Your Ideas, Bethel, CT: Crown House Publishing Company LLC.

- Margulies, N., and N. Mall, 2002, Mapping Inner Space: Learning and Teaching Visual Mapping, Chicago, IL: Zypher Press.

- Martin, R. L., 2007, The Opposable Mind: How Successful Leaders Win Through Integrative Thinking, Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

- Martin, R. L., 2009, The Design of Business: Why Design Thinking Is the Next Competitive Advantage, Boston: Harvard Business Press.

- Peters, D., 2007, “Team Launch System (TLS): How to Consistently Build High-Performance Product Development Teams,” The PDMA Toolbook 3 for New Product Development, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Polyani, M., 1966. The Tacit Dimension, Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Roam, D., 2010, The Back of the Napkin: Solving Problems and Selling Ideas with Pictures, New York: Penguin Group, Inc.

- Senge, P. M., 2006, The Fifth Discipline: The Art & Practice of the Learning Organization, New York: Doubleday.

- Senge, P. M, A. Kleiner, C. Roberts, R. B. Ross, and B. J. Smith, 1994, The Fifth Discipline Fieldbook: Strategies and Tools for Building a Learning Organization, New York: Doubleday.

- Sibbet, D., 2012, Visual Leaders: New Tools for Visioning, Management, and Organization Change, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Sibbet, D., 2010, Visual Meetings: How Graphics, Sticky Notes & Idea Mapping Can Transform Group Productivity, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Sibbet, D., 2011, Visual Teams: Graphic Tools for Commitment, Innovation, & High Performance, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

About the Contributors

- Karen A. Kreutz is a BS Chemical Engineer and Product Development professional who is passionate about “‘innovating how we innovate.”‘ She has 28 years at the Procter & Gamble Company in Open Innovation capability development and in the design of consumer-inspired products and marketing messaging. She is aspiring to make a difference in how the world collaborates for innovation by offering knowledge modeling services via ILUMINOV, LLC. She lives in Cincinnati, Ohio and is the mother of one son.

- Kim D. Benz is a BS Chemical Engineer and an Innovation professional with more than 40 years of product innovation experience. She first worked at the Procter & Gamble Company in the Research & Development, Product Supply, and Quality Assurance organizations. She then contributed via YourEncore and developed her own company—Onederings Lavender Farm with her sister. She is also a business partner in ILUMINOV, LLC. This collection of experiences gives her unique insights into the nature of innovation challenges in organizations and how to address them. She lives on a 110-acre tree farm in Clarksville, Ohio with her husband and is the mother of three children.