7

COLLABORATIVE INNOVATION ACROSS INDUSTRY-ACADEMY AND FUNCTIONAL BOUNDARIES: HOW COMPANIES INNOVATE WITH INTERDISCIPLINARY FACULTY AND STUDENT TEAMS

Jelena Spanjol, PhD

Associate Professor of Marketing

College of Business Administration

University of Illinois at Chicago

Michael J. Scott, PhD

Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering

College of Engineering

University of Illinois at Chicago

Stephen Melamed, IDSA

Clinical Professor of Industrial Design

College of Architecture, Design & the Arts

University of Illinois at Chicago

Albert L. Page, PhD

Professor Emeritus of Marketing

College of Business Administration

University of Illinois at Chicago

Donald Bergh, AIGA

Adjunct Assistant Professor of Graphic Design

College of Architecture, Design & the Arts

University of Illinois at Chicago

Peter Pfanner, IDSA

Executive Director

Innovation Center

University of Illinois at Chicago

7.1 Introduction

A recent global survey conducted by the Fraunhofer Society and the University of California Berkeley (Chesbrough and Brunswicker, 2013) indicates that 78 percent of large, public firms in Europe and the United States practice some form of Open Innovation (OI). Most organizations, furthermore, focus on inbound OI activities, where outside sources (such as customers or alliance partners) provide significant and critical input into a firm's new product development (NPD) process. Yet, despite organizations embracing collaborative forms to enhance their NPD portfolios, organizations in the survey also report dissatisfaction with both managing and measuring their OI initiatives. This is due, in part, to a company's desire to apply metrics to evaluating OI outcomes that are similar to those used in their core business practices. In this chapter, we describe a model of industry university collaboration that provides a structured and systematic approach to producing tangible, actionable insights and new product concepts for organizations. The specific program we describe has been developed at the University of Illinois at Chicago, where it is called Interdisciplinary Product Development (hereafter referred to as IPD).

What Is the Interdisciplinary Product Development Model? A Brief Overview

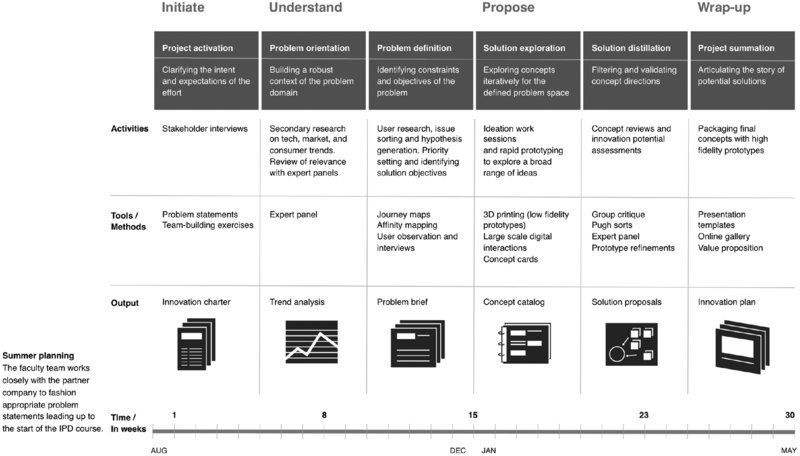

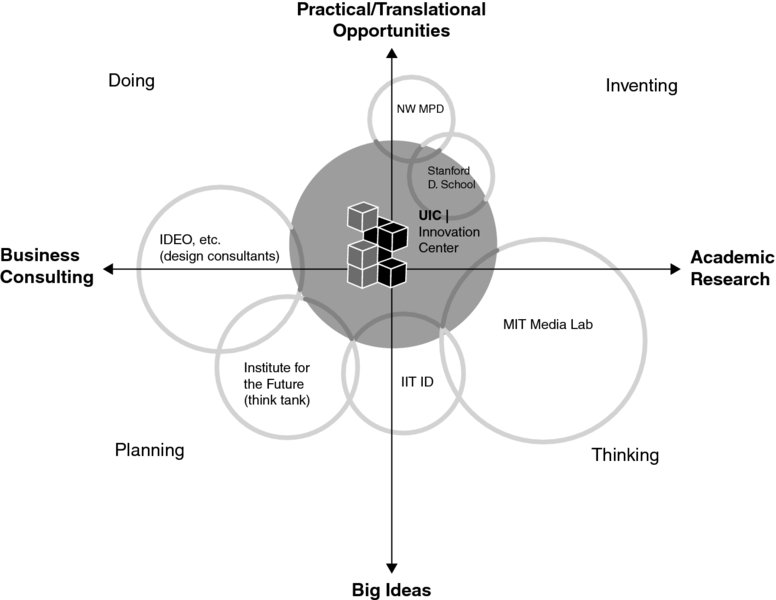

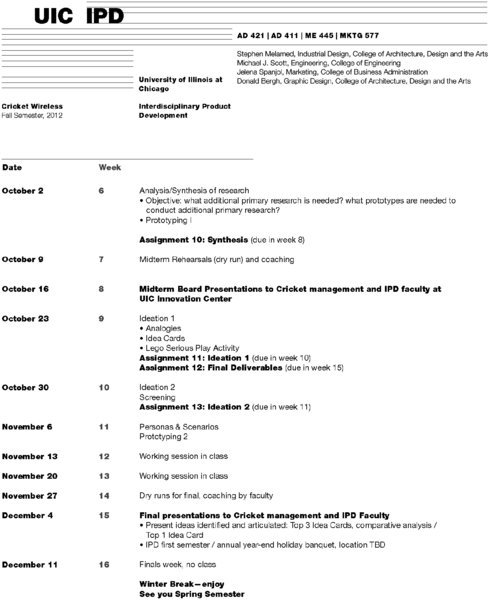

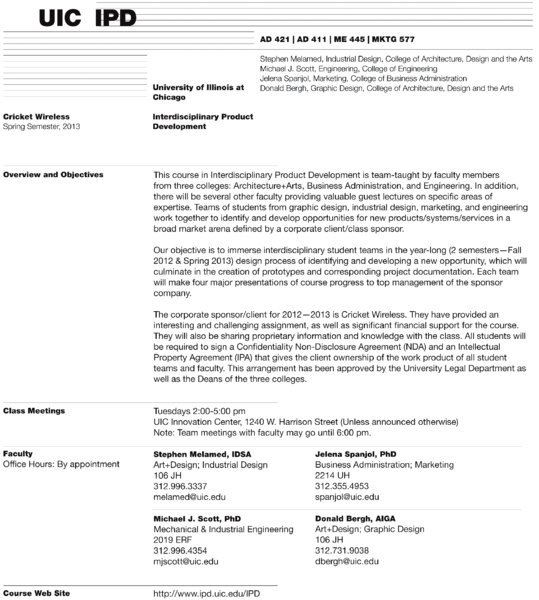

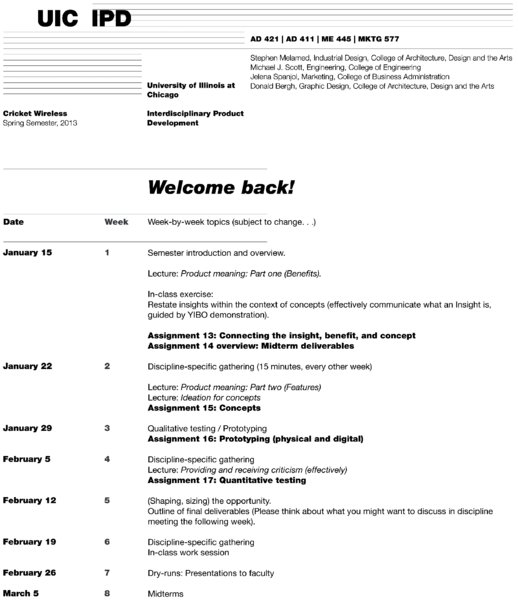

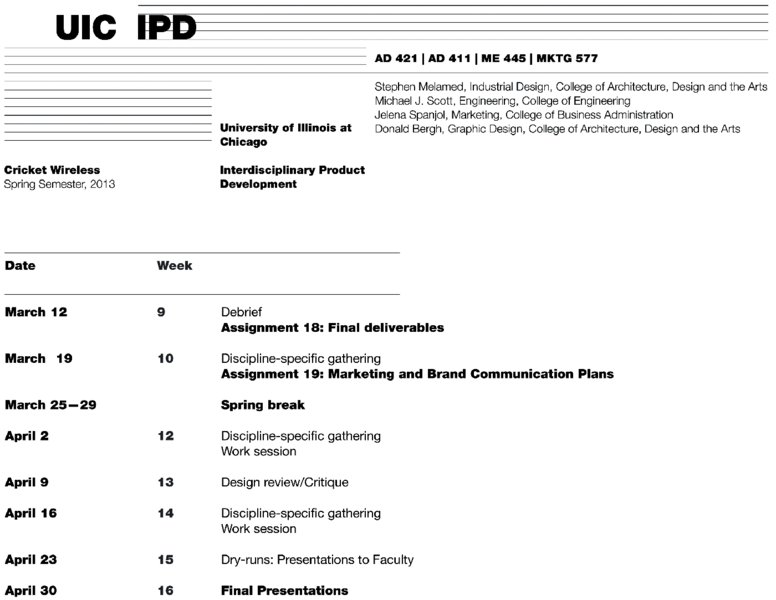

Interdisciplinary Product Development (IPD) is a two-semester (i.e., one full academic year) curriculum at the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC) in which cross-functional student teams collaborate with partner companies through the UIC Innovation Center (see Appendix A immediately following this chapter). IPD generates innovation for the partner company and provides a unique experiential educational opportunity for students from diverse disciplines within the university, including Business, Design, Engineering, and Medicine. Over the course of 30 weeks (i.e., two consecutive academic semesters), interdisciplinary student teams in IPD produce a body of knowledge that builds upon both primary and secondary research to offer actionable results for the partner organization to further develop or implement. Organizations that participate in IPD gain access to cross-functional student teams who bring fresh thinking (design thinking) and are guided by an experienced and dedicated interdisciplinary faculty team from business, engineering, and design in applying research, ideation, and prototyping techniques and processes to generate innovative solutions. Figure 7.1 graphically represents the IPD timeline and includes the major activities conducted during the program. (See Appendix B for recent syllabus exemplars.)

Figure 7.1: Overview of the IPD Process—Components and Timeline

Co-founded by business (Albert Page), engineering (Michael Scott), and design faculty (Stephen Melamed) in 2002, IPD has trained more than 500 undergraduate and graduate students in the best practices of a multi-functional approach to the front end of product development since its inception. Corporate partners—spanning diverse industries such as mobile communications, consumer electronics, household appliances, healthcare services and instruments, among others—have collectively received over 1000 new product concepts (some of which have resulted in patent applications) along with supporting user and market research. IPD is part of a small set of academic programs across universities worldwide, which emphasize close collaboration with industry partners to generate innovative solutions to applied problems while training the next generation of new product professionals. Please refer to Appendix E for a partial list of academic programs focused on new product development. At the time of its launch, only Carnegie Mellon University offered a one-semester course similar to IPD in the United States. Among the U.S. programs at least, IPD remains distinguished by its length (a full year rather than a single semester) and the equal partnership of three distinct disciplines.

The IPD model described in this chapter will help NPD practitioners develop an understanding of critical elements in OI initiatives, particularly when engaging with academic partners. The keys to success and pitfalls to avoid described in this chapter, while framed specifically within the UIC IPD model, are likely to apply to any course-based industry-university OI initiative. Importantly, an upfront investment in generating, evaluating, and selecting the most appropriate OI problem framing is critical to the success of such initiatives. Student teams become adept at working with the information provided by the partner organization and reframing the problem statement, supported by their research (both primary and secondary), in order to ensure that they are moving down a path to solve the right problem.

7.2 The IPD Model: Resolving Major Open Innovation Challenges

Innovation research indicates that a handful of critical factors predict new product success or failure. In the most recent PDMA Comparative Performance Assessment Study (Markham and Lee, 2013), companies that were most successful in their innovation efforts were those that followed proactive, first-to-market strategies, rather than reactive, follow-the-leader ones. As part of a proactive innovation stance, managers at successful companies emphasize the creation and use of intellectual property significantly more than the rest. This is partly achieved through OI, proactively seeking different viewpoints and tapping into knowledge bases outside of the firm in order to generate insights and ideas for new products (both manufactured goods and services), new solutions, and even new business models. Maximizing the variety and breadth of ideas in the innovation front end also maximizes the probability that more novel or breakthrough ideas are taken up and fed into the development funnel in firms. The importance of the front end is well recognized, with idea management being one of the critical drivers of successful innovation.

Although OI is reported to have increased steadily in frequency over the past years, it is not working as well as might be expected for a significant number of firms (Chesbrough and Brunswicker, 2013). A major challenge for many OI efforts is how to draw on and integrate viewpoints from multiple disciplines and stakeholders. Effective cross-functional teams are essential for successful new product development, requiring that all functions be involved equally rather than giving one particular function command over the project. A critical condition for translating cross-functional teams into increased new product performance is team integration and stability. When members on a team come and go, both team debate and decision comprehensiveness are hampered, reducing the possibility of creating a shared understanding of the problem domain and potential solutions (Slotegraaf and Atuahene-Gima 2011). Successful teams are able to balance individual initiative and the integration of cross-functional collaboration to effectively build upon each other's contributions in a meaningful way.

A second challenge in OI lies in effectively identifying and articulating the problem domain. Due to concerns regarding intellectual property protection and sensitive company information sharing, OI initiatives often require organizations to reduce, abstract, or cloak the specific innovation problem (e.g., in innovation contests) to such an extent that it becomes a narrowly defined, often technical problem and excludes the possibility for external participants to explore, refine, and redefine the problem domain as part of the innovation process. A potentially disadvantageous outcome of having to abstract and disguise the innovation problem is that external problem-solvers gear their efforts toward identifying a solution to a narrow problem, rather than toward understanding the problem prior to solving it. This is unfortunate, as reframing and redefining the problem to be solved can hold tremendous value for companies engaging in OI.

Finally, a third significant challenge for firms lies in effectively integrating OI efforts and outcomes into their internal NPD process, while protecting intellectual property (IP) and sensitive information. In the case of crowdsourcing (contest- or community-based), ideas generated might not get absorbed into the organization to the fullest extent possible, with only the top scoring solutions garnering managerial attention and integration.

In sum, three OI challenges can negatively affect the probability of success: (1) lack of functional integration and/or stability in OI teams, (2) incomplete or disguised OI problem statements, and (3) limitations in uptake of actionable outcomes from OI initiatives. As discussed next, these three critical factors are formally addressed by the UIC IPD model.

Overcoming Challenge 1: How IPD Creates Functional Integration and Stability in Open Innovation Teams

The success of OI initiatives, regardless of their form, depends critically on the engagement of innovation participants who are not part of the company. In the case of IPD, interdisciplinary student and faculty teams are both the external participants and drivers of the process for the partnering organizations.

IPD Faculty Team: Dual-Process Integration

THE IPD FACULTY HAS TWO MAJOR INTEGRATIVE ROLES. MORE SPECIFICALLY, THE IPD FACULTY HAS THE MANDATE TO INTEGRATE:

- companies with student teams, and

- functional perspectives into each component of the innovation process.

This dual-process integration role of the faculty team plays out in several different ways. To truly integrate all functional perspectives, the full faculty team is present at all class meetings and provides their discipline's perspective to the issues being addressed. Furthermore, all course materials and content (including assignments, lectures, in-class exercises, etc.) are developed jointly by the full faculty team. Not only is the content fully considered, but also the content delivery and the design of the materials. This fully interdisciplinary approach to course content development and delivery serves an additional educational objective—it models to the IPD student teams constructive dialogue between disciplines during every class session. Routinely, faculty from different disciplines question and probe each other's viewpoints, conclusions, and assumptions around the innovation topics discussed during class meetings, in front of the IPD student teams. This open dialogue among faculty instructs students from different disciplines to value input, build upon others' contributions, understand that there is no one single right answer and seek out questions from other perspectives.

The faculty team also functions as an integrative mechanism by translating priorities and input from the partner company to student teams. Importantly, the core mission of the IPD program is to train the next generation of innovation practitioners, minimize the anxiety of the unknown, and develop familiarity in dealing with complex multidimensional problems. It is imperative that the faculty team, rather than the partnering company, be the de facto “supervisor” of the student teams, for two reasons.

First, by allowing partner companies to select and steer student teams toward any specific identified innovation opportunity or concept, the company's existing business model is fed into the OI initiative. Predominantly, this leads to decreased novelty in the final concept and less value created for the partner company. Second, the faculty team is, by definition, focused on educating student teams on the process components of the front end of innovation. In contrast, partner companies are (again, naturally) focused on actionable outcomes. Part of this focus is, of course, due to the time pressures companies experience in identifying and bringing innovations to market. However, an overt focus on outcomes detracts from a full leveraging of the process employed in IPD (see Figure 7.1 for an overview). In essence, applying the process without skipping any steps generates greater novelty and value in the final innovation concepts presented to the participating firm by the student teams.

IPD Student Team: Interdisciplinary Integration and Engagement

On the student team side, several structural aspects ensure that both individual and team work are well supported. Of central importance is the workspace for IPD teams: the UIC Innovation Center (UIC IC; http://innovationcenter.uic.edu) is home to all IPD classes, as well as a resident interdisciplinary design team headed by the Executive Director. The UIC IC space supports interdisciplinary work by providing both large meeting spaces (plenary) to allow for collective, lecture-style content delivery and cross-team critique sessions, and smaller team spaces conducive to breakout activities including dedicated moveable team spaces (see Figure 7.2b). To facilitate (physical) prototyping work at various stages of the innovation process, student teams have access to a fully functioning prototype shop (see Figure 7.2c), including 3-D printing, computer-aided design tools, and other capabilities that encourage rapid prototyping and iterative low-fidelity models. Finally, to help student teams work through long sessions (a frequent occurrence that demonstrates the engagement of teams in the innovation challenge), the space provides a convenient gathering place complete with kitchen and espresso station (see Figure 7.2d).

Figure 7.2b: Dedicated Teaming Spaces

Figure 7.2c: Prototyping and Production Shop

Figure 7.2d: Kitchen: Encouraging Social Interaction

To support team cohesion, the IPD curriculum includes several team-building exercises—creating a team charter (specifying the rules of engagement, which each team develops on its own), talking and listening exercises, and Lego¯ Serious PlayTM (LSP) individual and team identification activities (see Frick, Tardini, and Cantoni, 2013), among others.

The faculty conducts weekly check-ins with the teams to ensure that any team issues are addressed in a timely and effective manner. At times, this requires convening additional sessions with teams dedicated solely to their issues. For example, one team was unable to reach consensus on which of the identified new product concepts should be pushed forward for further development. After an initial meeting with the faculty and multiple email exchanges, the faculty team developed a set of active listening exercises drawn from the clinical industrial psychology literature to demonstrate and train team members in constructive team debate. Such additional sessions with teams build on the core principles of effective critiquing that are explicitly taught in class with all students (see the sidebar on critiquing).

Overcoming Challenge 2: Ensuring Complete Problem Domain Definition and Exploration

OI initiatives are by definition designed to tap into knowledge bases that are located outside of the boundaries of the company seeking to innovate. This also implies a move from a Stage-Gate¯, decision-based process to a probe-and-learn, iterative innovation process. Students are encouraged to experiment, prototype, and test ideas early and often and are reminded that early failures may lead to a successful result in a more timely manner. The iterative approach to problem-solving is borne out in a continual revision of the problem domain and statement. The IPD model applies this process in two ways—by extensively working with the corporate partner to identify and define the initial problem statement student teams start with, and by tasking student teams to revise and redefine this problem statement over the course of two semesters, as additional information and learning is investigated and developed by the team.

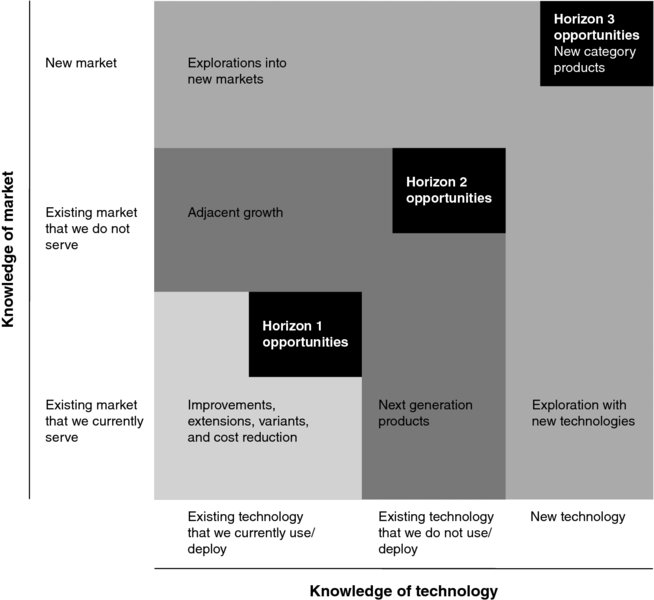

Naturally, the problem statement frames the entire innovation project and it is crucial to develop problem statements that define a domain that is sufficiently rich for proposing creative solutions, yet at the same time appropriately constrained so that teams can quickly move into primary, user-centered research. Developing a solid problem statement requires significant interaction between the corporate partner and the faculty team prior to the beginning of the class, and typically requires several iterations, which is why this is done during the summer prior to the start of the fall semester. To identify the starting point for potential problem statements in these initial conversations between the interdisciplinary faculty and corporate partner teams, the IPD faculty finds it helpful to frame the discussion in terms of the different innovation horizons (Terwiesch and Ulrich, 2009) in which companies engage (see Figure 7.3). The most effective level for IPD problem statements lies in Horizon 2 (i.e., exploration of adjacent technologies and markets, broadly defined), which allows the IPD Open Innovation initiative to uncover more innovative solutions and new white spaces related to the core capabilities of the participating firm.

Figure 7.3: IPD's Horizon 2 Focus

Source: Adapted from Terwiesch and Ulrich (2009)

Good problem statements generally share several traits. First, the problem statement must not presuppose a solution, or even the form of a solution. This means that the problem should be one of innovation, not implementation, so it cannot start with an idea, however good, generated by the corporate partner. It also means that the problem statement should avoid formulations such as, “Design an app to solve this problem.” Second, good formulations are often stated as an overarching problem statement with different filters that distinguish separate projects for separate teams. These filters can relate to demographics of user groups, to areas of the corporate partner's business, a focus on a technology or service, or to any other meaningful division of potential interest to the partner. Furthermore, effective problem statements can be needs-driven, technology-focused, or both. Technology-focused problem statements are particularly relevant when a company either possesses a potentially significant technology that is currently not used (or is used only in niche products) or is interested in acquiring an emerging technology. Needs-driven problem statements might focus on particular customers or situations to be addressed. Table 7.1 contains a set of examples of successful problem statements.

Table 7.1 Exemplars of IPD Problem Statements and Filters

| Problem Domain Approach | Corporate Partner Objectives | Problem Statement and Filters |

| Needs-driven | A housewares manufacturer partnering with the IPD course owned a large share of the consumer market for certain kitchen utensils, and wished to expand their business. | “Develop a new business that relates to our vision of total beverage solutions and relates to our current categories.” Filters: Each team chose a unique beverage from a list of interest to the partner: coffee, tea, hot drinks other than coffee or tea, alcohol, sport drinks, water, soft drinks. |

| Technology-driven | A market-leading designer of mobile communications products wished to explore innovative applications of select emerging and recently acquired technologies. | “Develop a significant new business opportunity for us.” Filters: Teams chose one of the following problem statements: “A product that utilizes expanded adoption of 4G network deployment in a cell phone/computer application.” “A consumer product that utilizes a user interface to control and/or monitor something within a home.” “Develop accessories which utilize the newly approved 3-D video standards.” |

| Hybrid: Technology- and Needs-driven | A market-leading mobile communications device manufacturer wished to reframe their solution space from technological features to usage benefits. | “Develop a new wireless communication device that extends wireless communication into new uses and new applications in the area of <filter> for emerging global consumer markets that should produce a $100 million revenue stream from the new product for us.” Filters: Teams chose one of the following areas: citizen journalism, commuting, connecting families, kids, medical, mobile money, travel, and wellbeing. |

| Hybrid: Technology- and Needs-driven | An automated retail company wished to explore business models for breakthrough self-service solutions. | “What is the future of automated retail?” Filters: Teams were tasked to identify and adopt their own filters, which included food, travel, and wellbeing, among others. |

Situating and Filtering Problem Statements

To provide a sufficiently deep context to the problem domain presented to student teams without imposing their business model or innovation approach, companies situate their initial problem statement within a presentation of their strategic vision of their business and how they view the marketplace at the very onset of the semester. For example, the housewares manufacturer (see Table 7.1) gave a presentation at the kickoff meeting (held during the second class of the first semester) that explained their problem domain of total beverage:

Total Beverage is our approach of looking at beverages from point of purchase to disposal to identify potential product opportunities. We want to know how consumers prepare, purchase, serve, enjoy, store, etc. their beverages and provide them with unique product solutions. Total Beverage includes, but is not limited to the following categories: Tea, coffee, juice, beer, wine, liquor, spirits, carbonated beverages, soda pop, sports drinks, kid's drinks, health beverages, powdered drinks, water, dairy, smoothies, floats . . . any and all hot or cold beverages.

The restriction that solutions should relate to “current categories” was a reminder that the partner's capabilities were in the production of housewares, not the provision of beverages, though it was made explicit that partnerships with beverage companies could be an acceptable part of a solution.

Similarly, the mobile communication devices manufacturer (also cited in Table 7.1) provided its vision of mobile communications and identified the filters accordingly. What is particularly interesting about the filter categories chosen by the mobile communication devices manufacturer is that they had already been identified by the company as categories of significant interest yet not quite high enough on the list of interesting categories to be assigned to any internal teams for action, a sort of “next ten” after the top ten that they were actively pursuing. This had great benefits in engaging the partner, as the problem statement was not simply an academic exercise but the next item that the partner would invest in as resources became available.

The identification of problem statement filters that are both relevant and important to the company engaging in the IPD program has proven to be a critical success factor for this type of OI initiative. A leading automated retail company decided to leave the identification and selection of problem statement filters up to the student teams, as they were interested broadly in the future of automated retail solutions. While each team eventually arrived at a filter, the lack of a bounded or constrained innovation problem led to greater uncertainty among the teams and forced them to cast a wider than usual exploration net. As a result, the in-depth exploration of a bounded problem space (whether defined by technology, needs, uses, or a combination of those) was reduced and delayed.

Continual Problem Statement Revisions

In the IPD program, we require student teams to rethink, reframe, and revise their initial problem statements throughout the course of the 30 weeks. The revision of problem statements over time clearly demonstrates how a team's perspective on the problem is changing and how greater understanding is being built. Over the years, the IPD faculty has witnessed two kinds of problem statement revisions: (1) the necessary funneling of a broad problem down to something more specific, and (2) the evolution of a problem with a good scope to one with better connection to consumer needs and use situations. Table 7.2 provides some examples across years that illustrate the two revision objectives. Importantly, teams that resist continual revising of their problem statements are less able to draw and integrate insights from the research conducted into their ideation efforts, leading to more incremental innovations. Teams that build and use deep insights to reframe and refine their problem statements are more likely to solve for an important unsolved problem the IPD partner company faces, thus increasing the likelihood of a more creative and useful final new product concept.

Table 7.2 IPD Problem Statement Revisions by Student Teams

| Revision Objective | Initial Problem Statement | Revised Problem Statements |

| Funneling (drive to specificity) | “What is the future of automated retail?” | Team A:

Team B:

|

| Use connectivity (anchor to needs) | “Develop a new wireless communication device that extends wireless communication into new uses and new applications in the area of <citizen journalism> for emerging global consumer markets that should produce a $100 million revenue stream from the new product for us.” |

|

| Funneling and use connectivity | “Develop mobile communication accessories which utilize the newly approved 3-D video standards.” |

|

User-Centered Research. What allows student teams to drill down and connect their revised problem statements to customer needs is the engagement of user- or human-centered research principles, which are grounded in design thinking and encourage the researcher to deeply understand what customers (whether in the B2B or B2C space) are experiencing. This fine-grained, rich understanding of customer problems, experiences, and needs is continually combined with “big picture” insights drawn from secondary research. Together, both primary and secondary research are gathered, organized, analyzed, and synthesized to help IPD teams frame the problem within the specific business landscape. In sum, IPD student teams engage in research as a discovery process, which sets the context for ideation and concept development and testing. This research is the groundwork to form hypotheses, from which IPD teams create personas, scenarios, and develop analogies to begin testing their hypotheses (see sidebar).

IPD student teams amass, collectively, hundreds of hours of interviews and observations in each of the IPD collaborations. This provides the basis for continuous learning, assumption testing-revising cycles, and ideation input. For example, while working with a mobile communications corporate partner, teams synthesized and extracted insights not only from interviews but also by nonparticipant observation of foot traffic trajectories across retail locations. Insights are abstracted not only in digital format but also actively integrated into the teamwork space in some form of physical manifestation, allowing for rich interaction between team members.

Ambitious Goals in Problem Statements to Encourage Breakthrough Thinking

For the mobile communication devices manufacturer, the goal of generating $100 million in revenue from the innovation was critical to setting the tone for the student teams and allowing them to think about expansive solutions, rather than incremental features. For the housewares manufacturer, the mention of a “new business” places the problem clearly within the realm of ambitious innovation: students are given the task of creating a product or product line that the partner can build an entire business around, not simply a new object for the partner to sell next to all its other offerings.

Overcoming Challenge 3: Integrating Actionable Outcomes into the Partnering Company

Integrating ideas, concepts, insights, and solutions from OI initiatives into a company's established NPD process is a major challenge. To address it, the IPD program ensures that student teams produce several tangible deliverables that can act as boundary-spanning objects between teams and the partnering organizations to communicate proposed solutions (via project books, presentations, prototypes, digital simulations, and marketing launch plans) and as input into the company's ongoing innovation efforts (via archived raw and processed collected data).

In conversations with new product managers and executives, it is not uncommon to hear about the challenges not only of conducting OI initiatives, but more importantly, about the puzzling problem of how to use the outcomes from such efforts. Two problems typically are highlighted: who is in charge internally of disseminating and incorporating insights into ongoing NPD projects, and how to effectively translate or adapt the format of the OI initiative output. The IPD program both recognizes and addresses these challenges by working closely with a dedicated team of managers from the partnering company. Close collaboration facilitates continual integration of outcomes (addressing the “who?” question) and effectively guides student teams to deliver project status information through formal presentations that are easily shared as well as archiving materials in an easily accessible format (addressing the “how?” question).

Sharable Insights: Formal Presentations, Project Books, and Marketing Launch Plans

IPD employs three main communication vehicles to support the partner companies in continually disseminating insights generated from IPD teams internally within their organizations—formal presentations, project books, and marketing launch plans.

Formal presentations are held four times during the 30-week duration of IPD (two midterm and two final presentations). The IPD faculty strongly encourages as many participants as possible from the partner companies to attend these presentations and depending on the location of the companies holds the two final presentations (one in each of the two consecutive semesters) on the premises of the partner company. Team presentations typically are formatted to be delivered concisely within 15 minutes, with each presenting IPD team also fielding a 15-minute question and answer session immediately following their presentation. On occasion, presentations may be followed by a “tradeshow style” Q&A in which members of the partner company move from team to team offering a more conversational style of providing input and feedback. The importance of these presentations is twofold: provide sharable project information and insights and encourage engagement by mentors from the corporate partner. Over the years, and not surprisingly, it has been demonstrated that frequent engagement by a greater number of managers from the corporate partner is positively correlated with both the quality and novelty of final outcomes.

One outcome of engagement that applies directly to the ease and effectiveness of sharing insights from the IPD teams into the partner organization relates to specific requirements a company might have for the presentation dek1 (i.e., a set of presentation slides) developed by IPD teams. Companies might request certain informational elements or an executive summary slide in a particular format to be included in the presentations in order to better facilitate dissemination within the organization. For example, one corporate partner requested that IPD teams follow their internal organizational practice of having a summary slide with key competitive and performance information relating to the proposed innovation. Importantly, only the informational elements of the summary slide were required of IPD teams, not the style and layout of the information (which was also prescribed internally in the partner organization).

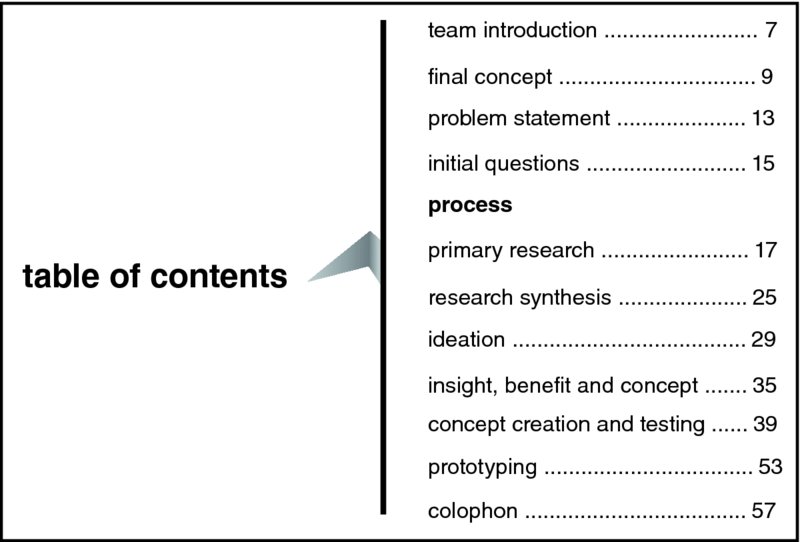

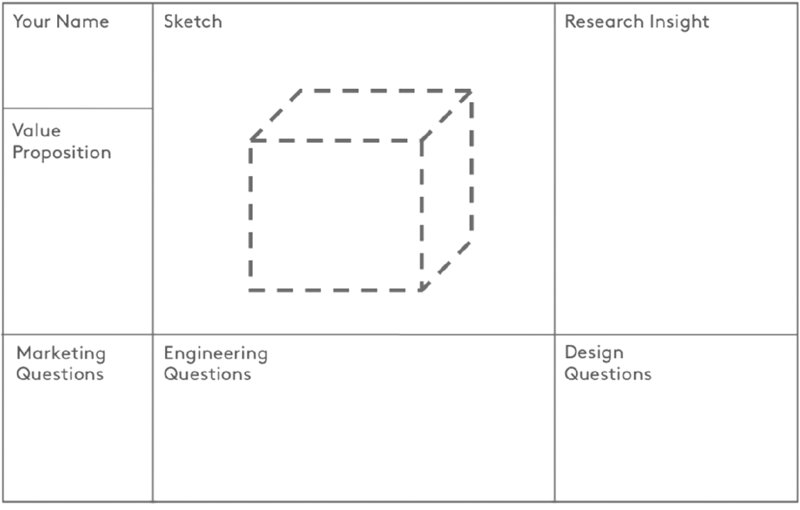

The second vehicle through which the work of IPD teams is summarized and shared within the partner company is the project book. This book differs from the presentation in that it tells the project's full “story” by abstracting main insights generated throughout the duration of the project and by highlighting pivotal input (e.g., pictures from primary data collection), process activities (e.g., research synthesis activities), and outcomes (e.g., idea cards). Idea cards, for example, capture and document a team's evolving thinking and represent the collective solution space the team is considering and from which a final concept is selected and prototyped. Idea cards serve three primary functions: (1) develop the idea itself, (2) document evolution of ideas, and (3) capture evolving team thinking. Figures 7.4a and 7.4b provide examples of IPD project documentation as a vehicle to share actionable insights. Figure 7.4a shows an example table of contents for a recent project book and Figure 7.4b shows the idea card template. Please also see Appendix C at the end of this chapter for an exemplar project documentation assignment.

Figure 7.4a: Example of a Table of Contents for an IPD Project Book

Figure 7.4b: Template for Idea Cards used by IPD Teams

The third formal communication vehicle in the IPD model is a detailed marketing launch plan for the innovation developed and proposed. Throughout the ideation and prototyping stages, teams are tasked to play through big-picture launch scenarios, which feed into the refinement of ideas and concepts. To support the viability of the proposed innovation, student teams generate a detailed marketing launch plan, including strategy, branding, geographic rollout focus (simultaneous across markets or staggered), promotional materials, and pricing. Forecasts of sales over the first one to five years are included for optimistic, pessimistic, and realistic sets of assumptions. Refer to Appendix D for an example of the detailed assignment given to student teams.

7.3 Concept Prototypes: Virtual and Physical

Prototyping features prominently in the IPD approach. Prototyping is employed both as a key vehicle to communicate the realization of a concept and as the main hypothesis-testing mechanism, driving forward in an iterative manner both decision making and conceptual development. Prototyping starts early on in user research and continues throughout ideation and concept development. Multiple benefits have been identified and confirmed from using prototyping in this expansive manner, including:

- Test implicit assumptions and hypotheses regarding potential users as well as the marketplace in general

- Create shared understanding among team members about insights and conclusions drawn

- Communicate value propositions in concepts to faculty and corporate partners

- Test iteratively to refine concepts and final renderings with potential users

Prototypes thus take on multiple forms, embodied at various levels of fidelity, from hypotheses regarding user experiences to drawings of potential solutions to physical (and virtual) prototypes for refining and testing designs.

Concept Prototype Example: Multigenerational Kitchen Space

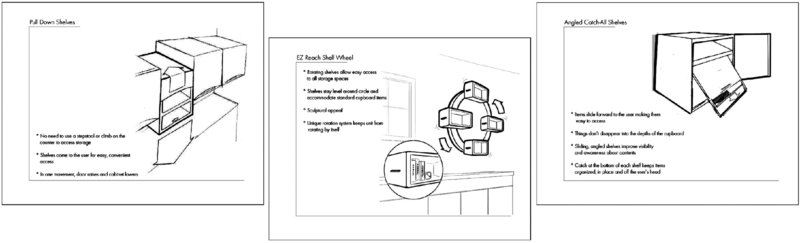

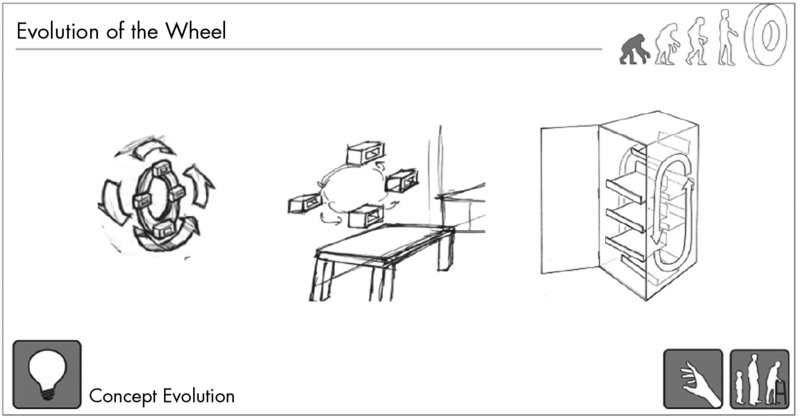

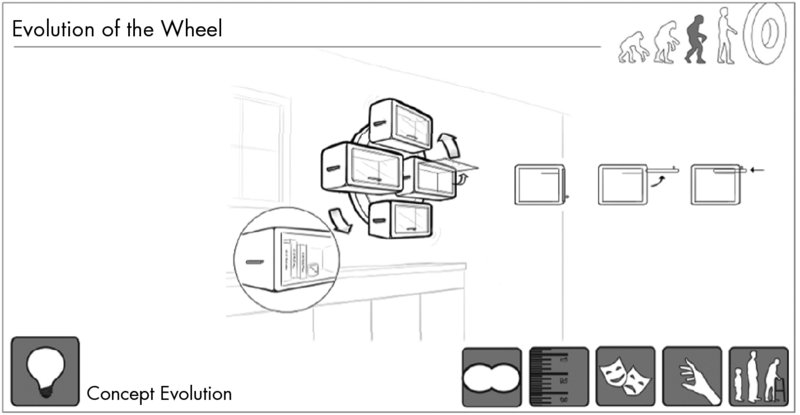

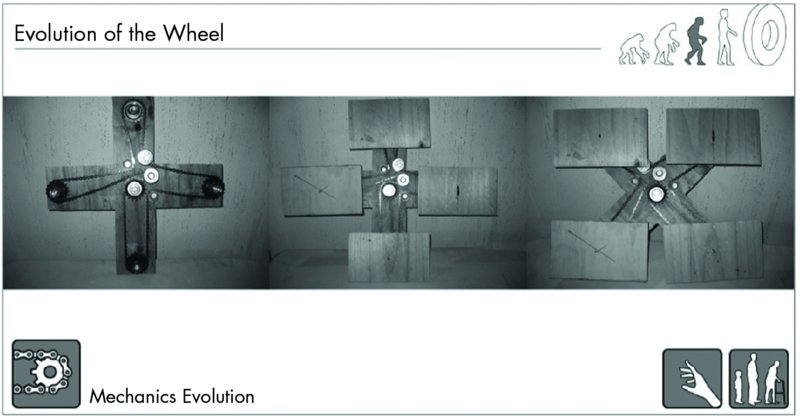

Figure 7.5 illustrates a set of concept cards for multigenerational kitchen solutions used to initially test out value propositions and user experience hypotheses with potential users.

Figure 7.5: Concept Card Examples

Figures 7.6a through 7.6d depict the selected concept in various drawing and physical renderings and demonstrates how a new product idea develops into a formal concept drawing and the various stages of functional prototypes.

Figure 7.6a: Final Concept Prototype Example 1

Figure 7.6d: Final Concept Prototype Example 4

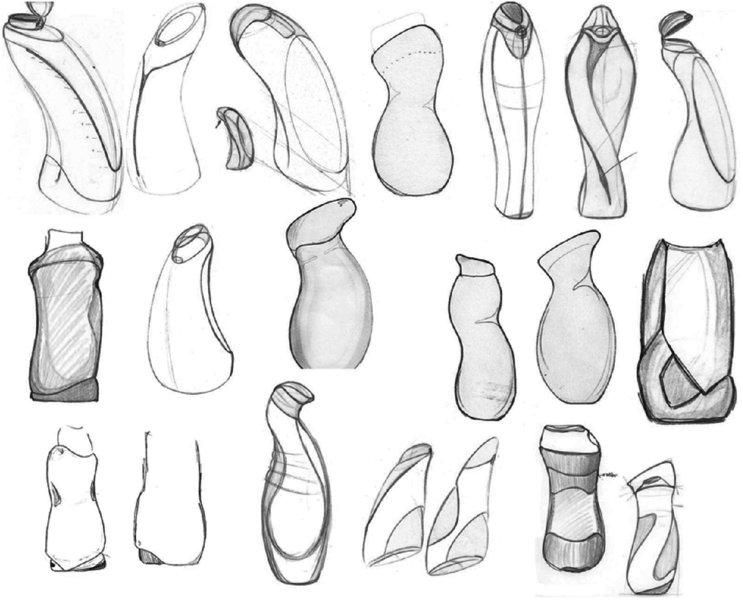

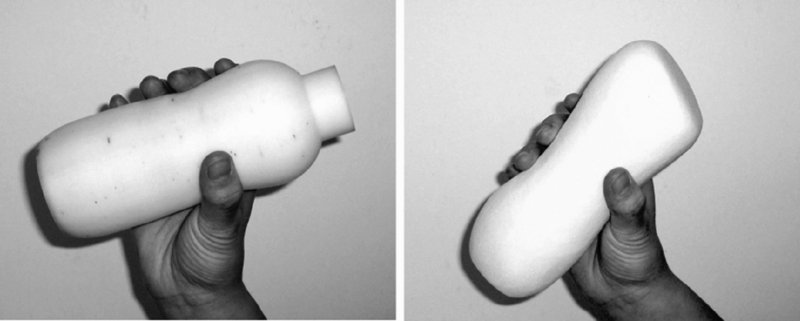

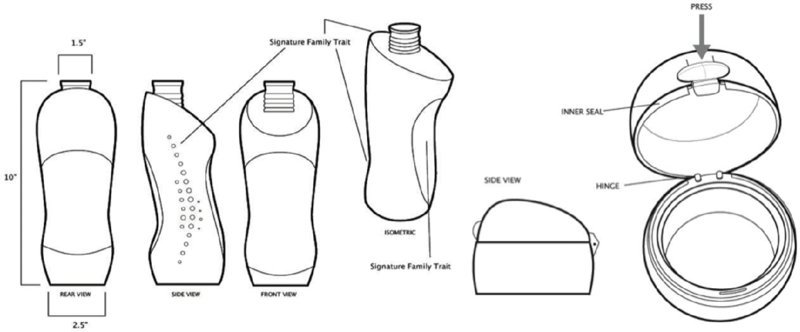

Concept Prototype Example: Portable Hydration Space

Similarly, Figures 7.7a through 7.7d show this progression from idea to final concept for a solution developed in the portable hydration space.

Figure 7.7a: Exploring Shapes and Ergonomics: Early Form Drawing:

Figure 7.7b: Exploring Shapes and Ergonomics: Early Form Physical Rendering

Figure 7.7c: Exploring Shapes and Ergonomics: Early Form Physical Rendering

Figure 7.7d: Converging on Final Design: Intermediate Form Drawing

7.4 Conclusion

In discussing the three major challenges of OI and how IPD addresses them, we have touched upon several of the tools and techniques used across the 30 weeks of an IPD engagement. Our discussion provides a short description of the major innovation process components in IPD (research, ideation, and prototyping), their primary objectives, and illustrative examples. Reflective of the interdisciplinary philosophy undergirding IPD, the tools and techniques employed are sourced from all three disciplines (engineering, design, and business). Furthermore, the tools and techniques employed are continually refined and updated as a concerted effort is made by the faculty to stay abreast of the newest insights generated by academic research and leading industry practices. For example, the faculty team decided against instructing student teams in brainstorming to generate concepts, as this technique has been demonstrated to lack both quantity and quality (see, for example, Mullen, Johnson, and Salas, 1991) when compared to individual idea generation or other ideation techniques, such as analogical thinking or ideation templates.

Engaging with an academic partner to explore potential innovations to selected problem statements can have unintended benefits beyond the insights and innovation concepts generated. The IPD faculty often finds that companies absorb and adopt some of the process elements employed in our IPD program, diffusing the learning from this OI initiative into the in-house innovation approach. Because the IPD program offers a lab for experimentation that sidesteps the company's established innovation hierarchies and routines, IPD outcomes also offer an opportunity for the industry partners to engage in multiple parallel “small bets” in the innovation space. Rather than looking for one single best solution, the IPD initiative allows companies to explore many different potential solutions across markets, which are developed sufficiently to warrant an internal review by the end of the IPD engagement.

As the IPD program continues to grow and evolve, novel ways of leveraging this OI format are emerging. For example, smaller projects that run over shorter time periods and draw students across different disciplines with specific skill sets and professional development goals have been instituted on a trial basis. In addition to the challenges they share with other IPD offerings (e.g., effective problem statement definition and revision), new ones are also encountered (e.g., operating within and across traditional semester schedules) requiring novel solutions and approaches. What remains abundantly clear, however, is that OI initiatives in the form of the IPD program hold tremendous potential for companies and students alike.

References

- Chesbrough, H., and S. Brunswicker, 2013, Managing Open Innovation in Large Firms. Germany: Fraunhofer Verlag.

- Frick, E., S. Tardini, and L. Cantoni, 2013, LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY™. White Paper. Available at: www.adam-europe.eu/prj/10330/prd/1/1/s-play_White_Paper_.pdf.

- Markham, S. K., and H. Lee, 2013, Product Development and Management Association's 2012 Comparative Performance Assessment Study, Journal of Product Innovation Management 30(3): 408–429.

- Mullen, B., C. Johnson, and E. Salas, 1991, Productivity loss in brainstorming groups: A meta-analytic integration, Basic and Applied Social Psychology 12(1): 3–23.

- Slotegraaf, R. J., and K. Atuahene-Gima, 2011, Product development team stability and new product advantage: The role of decision-making processes, Journal of Marketing 75(1): 96–108.

- Terwiesch, C., and K. T. Ulrich, 2009, Innovation Tournaments: Creating and Selecting Exceptional Opportunities, Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business Press.

Appendix A

The UIC Innovation Center: An Interdisciplinary Home for IPD

The Innovation Center (IC) is a collaboration, education, and development center embedded in the University of Illinois at Chicago (UIC). A tier one research university with 15 Colleges including Architecture Design and the Arts, Engineering, Business Administration and Medicine, among others. The UIC IC initiates programs and participates in activities that bridge research and education with industry. The UIC IC leverages the holistic and interdisciplinary nature of design to cut across research and to move projects from research into development.

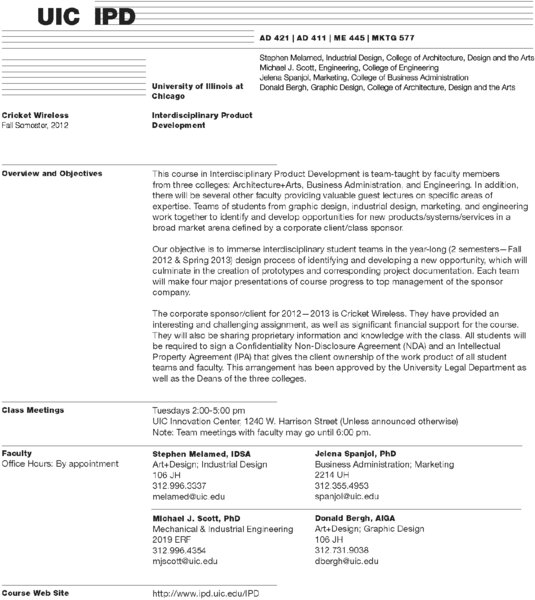

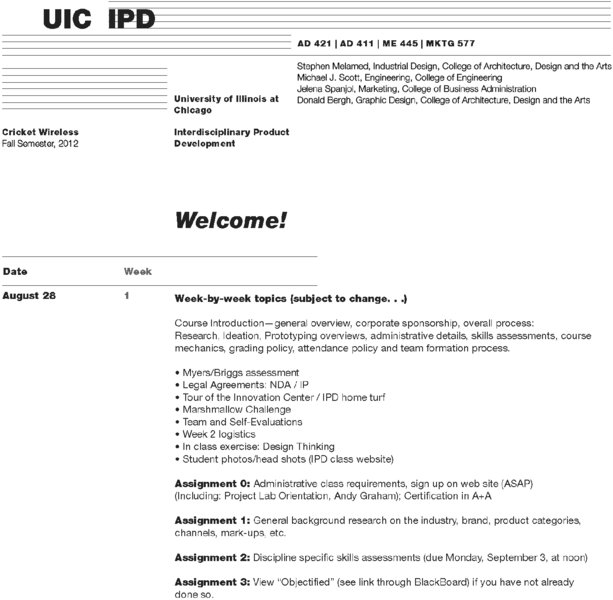

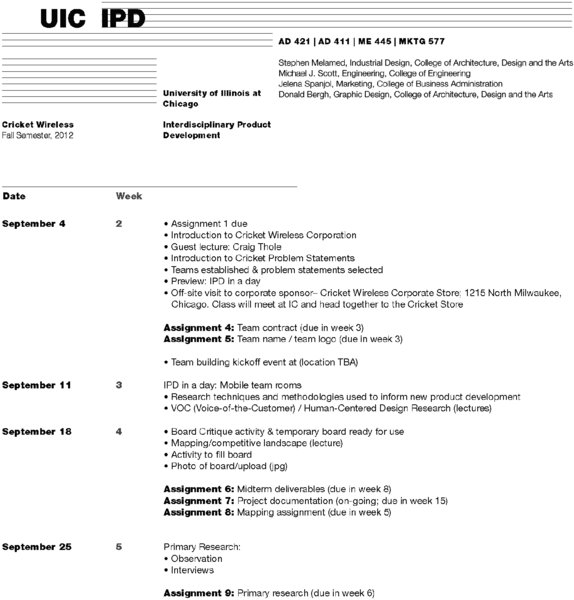

Appendix B

Sample Syllabi (Fall 2012/Spring 2013)

Appendix C

Project Documentation Assignment (Fall 2012/Spring 2013)

Appendix D

Marketing Launch Plan Assignment (Fall 2012/Spring 2013)

Appendix E

Selected Open Innovation Academic Programs

The following is a partial list of academic programs collaborating with industry partners in order to generate innovation.

| School | Program Name | Location |

| Aalto University/ Helsinki University of Technology | International Design Business Management program (IDBM) | Helsinki, Finland |

| Arizona State University | InnovationSpace | Tempe, AZ USA |

| Bandung Institute of Technology | Center for Innovation, Entrepreneurship, and Leadership | Bandung, Indonesia |

| Bentley College | MS+MBA In Human Factors in Information Design | Waltham, MA USA |

| Boston University | Strategy & Innovation Department | Boston, MA USA |

| Carnegie Mellon University | Integrated Design Innovation Group | Pittsburgh, PA USA |

| China Europe Int'l Business School | CEIBS Center of Marketing & Innovation (CMI) | Shanghai, China |

| Christchurch Polytechnic Institute of Te | Graduate Diploma in Innovation and Entrepreneurship | Christchurch, New Zealand |

| Delft University of Technology | Industrial Design Engineering | Delft, Netherlands |

| DePaul University | New Product Management Concentration (MBA) | Chicago, IL USA |

| Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne | Corporate Strategy & Innovation | Lausanne, Switzerland |

| European Business School (EBS) | Strascheg Institute for Innovation and Enterpreneurship Compentence Center Innovation Management |

Oestrich-Winkel, Germany |

| Fachhochschule Brandenburg University of Applied Sciences | Master TIM – Technology and Innovation Management | Brandenburg, Germany |

| Georgia Tech College of Management | TI:GER Technological Innovation: Generating Economic Results | Atlanta, GA USA |

| Hochschule Pforzheim University | Master's Program in Product Development | Pforzheim, Germany |

| IAE AIX Graduate School of Management - Universite Paul Cezanne | Master of Global Innovation Management | Aix-en-Provence, France |

| INSEAD | Blue Ocean Strategy Institute | Fontainebleau, France |

| MIT | MIT SLoan MBA Entrepreneurship and Innovation Program | Cambridge, MA USA |

| Massey Univeristy | Centre for Product Innovation | Auckland, New Zealand |

| Michigan State University | School of Packaging | East Lansing, MI USA |

| Milwaukee School of Engineering | Master of Science in New Product Management | Milwaukee, WI USA |

| National University of Singapore | Division of Engineering & Technology Management (ETM) | Singapore |

| North Carolina State University | Center for Innovation Management Studies | Raleigh, NC USA |

| Northwestern University | Center for Research in Technology and Innovation (CRTI) | Evanston, IL USA |

| NYU Stern School of Business | MBA Specialization in Product Management | New York, NY USA |

| Portland State University | MBA Innovation Management and Entrepreneurship Concentration | Portland, OR USA |

| Purdue University | Technology Realization Program | West Lafayette, IN USA |

| Rensselaer Lally School Of Mgt. & Technology | Severino Center for Technological Entrepreneurship | Troy, NY USA |

| Rochester Institute of Technology | Master of Science in Product Development | Rochester, NY USA |

| Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University | Management of Technology and Innovation | Rotterdam, Netherlands |

| Ryerson University | MBA/MMSc in the Management of Technology and Innovation | Toronto, ON Canada |

| SKEMA (formerly Ceram Business School and ESC Litlle School of Management) | Entrepreneurship, Technology and Innovation (ETI) | Euralille, France |

| State University of New York Institute of Technology | MBA in Technology Management | Utica, NY USA |

| Stevens Institute of Technology | Technology management Major | Hoboken, NJ USA |

| Tampere University of Technology | Citer - Center for Innovation and Technology Research | Tampere, Finland |

| Technical University of Hamburg Institut | Produktentwicklung, Werkstoffe und Produktion (Product Development, Materials and Production) | Hamburg, Germany |

| Technische Universiteit Eindhoven | Innovation Management | Eindhoven, Netherlands |

| Temple University | The Innovation & Entrepreneurship Institute | Philadelphia, PA USA |

| Texas A&M University | Product Development Center (PDC) | College Station, TX USA |

| Tsinghua University | Research Center for Technological Innovation | Beijing, China |

| University College Cork | Masters in Management & Marketing | Cork, Ireland |

| University Erlangen-Nuremberg | Department of Industrial Management | Nuremberg, Germany |

| University of California Irvine | Don Beall Center for Innovation and Entrepreneurship | Irvine, CA USA |

| University of Cambridge | Centre for Business Research: Enterprise and Innovation Programme | Cambridge, UK |

| University of Detroit Mercy | Master of Science in Product Development Program | Detroit, MI USA |

| University Of Dublin | Masters in Innovation and Technology Management | Dublin, Ireland |

| University of Duisburg-Essen | Executive MBA at the Zollverein School of Management and Design | Essen, Germany |

| University of Florida | Integrated Product and Process Design Program | Gainseville, FL USA |

| University of Greifswald | Ideenwettbewerb10 | Greifswald, Germany |

| University of Groningen | MSc BA Strategy & Innovation | Groningen, Netherlands |

| University of Ilinois at Chicago | Interdisciplinary Product Development (IPD) | Chicago, IL USA |

| University of Manchester | CRIS - Consumer, Retail, Innovation and Service Group | Manchester, UK |

| University of Maryland | Center for Advanced Life Cycle Engineering (CALCE) | College Park, MD USA |

| Università di Modena e Reggio Emilia | Master of Science in Engineering Management | Modena, Italy |

| University of New Hampshire | Part-time MBA Specializations Marketing and Supply Chain Management | Durham, NH USA |

| University of Notre Dame | ESTEEM | Notre Dame, IN USA |

| University of Pennsylvania Wharton School of Business | IPD Integrated Product Design | Philadelphia, PA USA |

| University of Regensburg | Innovation and Technology Management | Regensburg, Germany |

| University of San Diego | MBA Marketing Emphasis | San Diego, CA USA |

| University of Southern California | Stevens Institute for Innovation | Los Angeles, CA USA |

| University of Southern California | Graduate Certificate in Technology Commercialization | Los Angeles, CA USA |

| University of St. Thomas - Minnesota | School of Engineering Product Development Certificate | Saint Paul, MN USA |

| Universiteit Twente | Patterns in NPD | Enschede, Netherlands |

| University of Utah | MBA & MS Engineering | Salt Lake City, UT USA |

| University of Wales Inst Cardiff | MBA in Product Design | Cardiff, Wales |

| University of Waterloo | Master of Business, Entrepreneurship and Technology (MBET) | Waterloo, ON Canada |

| Virginia Commonwealth University | The Da Vinci Center for Innovation in Product Design and Development | Richmond, VA USA |

| WHU Otto Beisheim School of Management | Chair of Innovation and Organization | Vallendar, Germany |

| Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK) | The Institute of Design and Technology | Zurich, Switzerland |

About the Contributors

- Jelena Spanjol, PhD, is Associate Professor of Marketing in the Liautaud Graduate School of Business at the University of Illinois at Chicago. She received her doctorate from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Her research investigates marketing and innovation strategy and decision making, as well as managerial and consumer goal-striving dynamics. Jelena's research has been published in the Journal of Marketing, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, Journal of Product Innovation Management, Marketing Letters, Journal of Business Ethics and Health Psychology, among others, and in various book chapters.

- Michael J. Scott, PhD, is Associate Professor and Director of Graduate Studies in the Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering at the University of Illinois at Chicago. He is also Director of the Interdisciplinary Product Development (IPD) program. He commutes by bicycle year-round.

- Stephen Melamed, IDSA, is an Industrial Designer and Design Educator. He is currently a Clinical Professor of Industrial Design at the University of Illinois at Chicago and the Associate Director of the Interdisciplinary Product Development program at the UIC Innovation Center. Stephen is also a principal in the Tres Design Group, an award-winning design firm that has won international recognition working in diverse industries both domestically and abroad.

- Albert L. Page, PhD, is Professor Emeritus of Marketing at the College of Business Administration, University of Illinois at Chicago. He earned his MBA and PhD degrees from Northwestern University. His research and teaching interests focus on product development, particularly metrics for measuring and improving product development performance. He has published articles in many of the leading journals in the marketing area, including several articles in JPIM. Dr. Page is a long-time member of the Product Development & Management Association (PDMA), has held several offices within the association, and was its president from 1994–1995.

- Donald Bergh, AIGA, is an Adjunct Assistant Professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, currently teaching Interdisciplinary Product Development. He has been involved in design education since 1983; teaching at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, The Institute of Design at the Illinois Institute of Technology, and the University of Illinois. Outside of teaching, he has had a wide range of professional experiences, from Design and Publications Director at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; to Design Director of the McKinsey Quarterly at McKinsey & Company; to being a partner at Iota, a sensor-based research firm. Donald is a Graham Foundation Design Fellow, and received his BFA at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design. He also attended the Yale/Brissago Design Program.

- Peter Pfanner, IDSA, is Executive Director of the Innovation Center at the University of Illinois at Chicago, and holds a Bachelor of Applied Science in Environmental Design (Industrial Design) from the University of Canberra, Australia and a Master of Design Methods from the Institute of Design, Illinois Institute of Technology. Peter has 25 years of experience as a designer, design manager, design director, creative director, innovator, and educator working in industrial design, innovation, interaction design, and experience design at corporations, consultancies, and universities in Asia, Europe, and the United States in multiple fields including mobile communications, consumer electronics, medical, office products, furniture, architecture, materials science, and innovation. He has over 20 design and utility patents and is a 1st Dan Black Belt in Tae Kwon-do.