10

HOW TO WORK WITH SMALL COMPANIES TO EXPAND YOUR OPEN INNOVATION CAPABILITIES

Donna Rainone

PCDWORKS

Mike Rainone

PCDWORKS

Louise Musial

PCDWORKS

10.1 Introduction

The lessons presented in this chapter are devoid of statistics and methodology; they are not derived from even one survey, but rather are the notions, insights, and lessons learned by a new product development (NPD) company that has spent 25 years of ideating, engineering, designing, and commercializing products for and with some of the largest organizations in the world. There are no checklists, not an algorithm to be found, nor a formula, even the case studies are few; everything discussed should be considered heuristic in nature and is the result of the painful lessons learned from actually doing new product development and innovation both for big corporations and for our own portfolio.

This chapter will provide insight for engaging small companies for your Open Innovation (OI) initiatives. It is essentially a thought guide for building a partnership between you, “the company,” and the small company (“the vendor”). While dealing with small companies and utilizing outside resources is hardly a new idea, the ever devolving infrastructure of larger entities has made it harder and harder for “vendors” to work with “the company.” First, however, we must address why this is so.

One can be fairly certain that by this date, most individuals working within corporate walls will have realized that attempts to somehow drag “Corporate America” into a new Renaissance of innovation have failed or are, at best, lethargic. Over the past few years, more particularly, starting with the collapse of 2007, real attempts to jumpstart corporate innovation have gone for naught. For the past few years, headlines in every part of the media have repeated the mantra of how innovation will save us all. Corporate America's embrace of innovation has not happened, nor will it pay any more than the lip service that it currently pays. According to a recent study, “Business investment in equipment, software and structures grew by only 0.5 percent from 2000 to 2011 compared to an average of 2.7 percent between 1980 and 1989 and 5.2 percent per year between 1990 and 1999” (Atkins and Steward, 2013). However, implementing OI practices is a way for corporations to realize the fruits of innovation without having to pretend to build a culture of innovation within.

The OI that we are addressing is the truest sense of openness, which is the notion that a corporation must open its doors, heart, and mind to those outside its walls to find its next idea, to learn effective problem-solving, and to develop the disruptive technologies that are required for breakthrough product development. Corporations must overcome the fundamental and toxic “Not Invented Here” antipathy inherent within product teams that have been saddled with sustaining engineering and incremental improvement for too long. These teams, well intentioned as they might be, are often the toxins that prevent corporations from adopting a true spirit of Open Innovation, and these toxins must be neutralized. Please note that OI may mean portals and platforms and websites, but true Open Innovation means reaching out for the experts, thinktanks, inventors, and product developers who would never throw their wisdom through the staged portal of an open casting call.

10.2 Definitions

It's important to clarify terms and definitions of what OI is before we get started in this chapter. There have been many circumstances in which the term open innovation has been interpreted differently for each individual sitting at the table. Some associate it only with crowdsourcing while others view it as a tool for seeking external ideas and knowledge. Throughout this chapter, Open Innovation will be defined as: The use of external ideas, individuals, and companies, along with ideas, tools, and opportunities internal to the corporation, to advance technology development to create value. This, in this context, is a very broad and all-encompassing term. It allows for any source of innovation, whether crowdsourcing/competition platforms, small consulting companies, universities, garage inventors, or “Makers” to be included in the OI conversation within any corporate NPD initiative.

10.3 Background of Open Innovation

Most companies have been practicing OI for years. When one brings in an expert from a university to do applied research on materials or a technical consultant to help with a packaging problem, one engages in OI. However, in 2003, Dr. Henry Chesbrough wrote Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology, a book in which he more formally described a brave new world of outsourced innovation. He talked about a world that promised reduced risk and quicker profits for companies willing to open themselves to collaboration with the creative folk lying just outside of their corporate doors. Chesbrough was trying to alert us to the very reality that with the current technological velocity, companies just wouldn't be able to keep up. Looking externally for help was the only way to stay on the cutting edge.

Since the publication of Chesbrough's book, the OI movement has taken off. Crowdsourcing entities like Six Sigma and InnoCentive came into existence, poised to take your toughest technical problem and throw it to their cloud of experts who, though scattered around the world, would find a quick solution. This led to the current crowdsourcing phenomenon that not only fixes tough technical problems, but is used to develop everything from logos to software. Cash-strapped inventors can even use crowdsourcing sites like Kickstarter to help raise startup funds.

Chesbrough had good justification for his ideas. First and foremost, he rightly states that technology is moving too fast for any of us to keep up, and what was true in 2003 is more valid today. As many corporations strive to stay lean, they have cut out the fat—often in the form of older engineers approaching retirement. This culling of accumulated wisdom very often leaves no one with the ability to put the exponentially growing body of the world's knowledge to work. Even when there is a decent engineering function left standing, most engineers are saddled with sustainment, or with the incremental changes that are required to fit customer needs. If we believe in Peter Drucker's notion that the two most important functions of any business is Marketing and New Product Development, this culling of older engineers leaves no knowledgeable folk around to manage NPD, which then makes NPD the riskiest part of every corporation's main function.

More now than ever companies are being forced to reconcile the possible benefit of innovative new products with the risks inherent in the process of development of those innovations. We all know that innovation is messy, unpredictable, full of unknowns, and risky. If you can't predict the endpoint, final development expenses, or payoff, then the corporate accountants cannot quantify the risk. OI reduces the risk by letting someone else take the gamble of discovering, developing, and testing the market with the new technology. Many companies believe that it's cheaper to pay for a developed, market-ready technology than be burdened with an unruly, unpredictable, uncompromising, uncooperative group of crazies (also known as an NPD R&D staff) going down that rocky NPD road into the unknown.

10.4 Two Paths: The Intraprenurial Organization versus the Outsourced Organization

Given that it is difficult for the large corporation in most cases to have predictable innovation processes, there seems to be two paths that one can follow. First, one can acknowledge that innovation is difficult and should be outsourced, at least in its early stages. This is reflected in the current strategy of “buying innovation” by acquiring a successful startup. This is especially profound given how poorly large companies are able to manage the same functions. The alternative, the intrapreneurial organization, is that one may take the path of trying to emulate what small successful startups do, but to do it underneath the tent of the large organization. While in some ways this seems less risky because of the “reign” one can put on internal resources, such a culture within a culture is very difficult to maintain for a variety of reasons.

If we agree with the supposition that small entities are better at innovation, we should examine the factors that make them better, as we do below.

Small Companies Are Agile in Adapting to Changes in the Environment

When dealing with technology development and game-changing innovation, common sense and overwhelming evidence suggest that teams should be small—something central to small innovative organization. At the very core of this is the fact that innovation teams must be very adaptable in order to change direction not if, but when there is a scope change or if an unknown becomes known. An organization must be able to swiftly adapt to the changing situations, and a small organization or team is the fastest way to navigate those hurdles. Larger entities must put into place the mechanism that allows them to behave like smaller organizations in the world of innovation. They must learn to be agile, flexible, and without the normal constraints of the larger entity. If this sounds like an insurmountable problem for a large entity, well, frankly it is. Fortunately, by recognizing that failing, adjustments can be made.

Small Companies Are Quick at Decision Making

No one who has ever suffered in a large bureaucracy has anything positive to say about the speed of decision making. There are no doubt a myriad of factors that the make decision making slow and ponderous in a large entity. We won't go into detail here, except to mention the focal reasons, and that is the fact that large entities are not entrepreneurial, they are not “flat,” and they often have much more to lose for bad (or risky) decision making Rarely are there consequences for those truly at fault when a large corporation stumbles. Even if the financial risk is small, large corporations are very aware of the damage that can be done to their brand by even the slightest blemish, especially in this time of social media such as Twitter and Facebook. So, small organizations can make decisions quicker and with smaller risk, which allows everything to move faster. Furthermore, small organizations, almost by definition, have little or almost no bureaucracy. Decision making happens fast because there is usually one decision maker who has real-time information by which to make the decision.

Small entities are typically run by entrepreneurs who have detailed knowledge of every aspect of their business; the information required to make a decision is already in the hands of the decision maker. The small business decision maker, having to make many different decisions daily, has a better feel for the process than someone at the top of a corporate hierarchy who must rely on reports from those below to make a decision. That corporate decision making may be further speed-bumped by having to weigh the effects that a decision may have on shareholders, boards of directors, and other stakeholders.

Small Companies Have a “Do or Die” Mentality

Most small companies have a highly motivated leader and workforce. The successful small organization is more cohesive because it is easier to rally the workforce around the central vision of the leadership. Everyone in the company is an important contributor. There's not a place to hide in a small entity. If you are not contributing, you are a drag on progress and success and this become obvious very quickly. There is also a sense of pride in participating in creating something from nothing.

Small entities are typically run by entrepreneurs who have come to terms with their own risky positions. Small entities must be adept at problem-solving on every level—not just the innovation side for NPD firms. On a daily basis, they are forced to solve problems on how to engage new customers without large budgets, how to make payroll without lines of credit, how to stay visible without a PR team behind them. Most entrepreneurs are driven because they want to be part of something bigger, not because they want a pay check. If you want to find innovators, you must look at small organizations that want to create and do something big. The typical entrepreneurial startup has a vision of where it wants to go and is able to articulate and control the steps to get there without having to answer to a corporate hierarchy.

Most large companies don't like failure; they view it as putting their core business at risk. No matter how much they say that failure is acceptable, we all know it's usually not. We, especially Americans, don't like the idea that we aren't the best or that we make mistakes. If we take failure as a given in developing new products, the small companies can fail quicker, cheaper, and faster. Innovation doesn't always involve failure, but it has to be an acceptable part of the process. Small entities have learned this lesson many more times over than large and impersonal organizations. Entrepreneurs are risk takers by nature; they accept failure as part of the process.

Small Companies Often Are More Able to Retain Their Human Capital

Small entities by their very nature want to and have to retain employees, especially those who are working on highly complex and challenging areas. One can never underestimate the importance of the human capital: It's not a company that innovates; it is a person within organizations who innovates. There is no such thing as a collective mind; it is the individual mind that makes the connections and one can never tell from which individual that connection will come. Thus, it is absolutely imperative for small innovative companies to retain their intellectual capital, the capital that is held in the minds of their employees. Often small innovative companies work on a technology's leading or “bleeding” edge, which refers to the very forefront of technological development, or an increased risk of “metaphorically cutting until bleeding” because of the unreliability of the technology. Often, trade secrets created in the small company's workforce are more valuable than patent-based IP. A small company can provide the longevity and continuity a large company cannot. One of the great problems of large corporation innovation is that once an innovation team has succeeded, most of the individuals, those who have been “champions” of a product, want to continue in that role. If there is no sustained innovation pipeline, retaining that human capital of accrued wisdom is difficult.

What Can a Large Company Learn from a Small Company?

Of all of the lessons that can be learned from the small innovative company, one of the most important is entrepreneurship. From American to European corporations, everyone is touting the importance of being an entrepreneur. What is it about entrepreneurship that has corporate America so excited? If you are an entrepreneur, it's fairly easy to look at what happens day to day and compare it to what is not happening in a big corporation. One supposes that it's the entrepreneur's willingness to push forward, to drive to solutions without being prodded to start. Being an entrepreneur requires enthusiasm, risk-taking, self-motivated energy; it also suggests something that most corporations don't have, or have intermittently, and can never reliably get under normal conditions, which is a sense of ownership. At the end of the day, the real essence of entrepreneurship is a sense of ownership; the realization that it all depends on you and nothing is going to get done unless you do it. The real sense of entrepreneurship requires that employees act as owners. As has been said, “If you want to be an owner, act like an owner.” The corollary of that is if you want employees to behave like owners, treat them like owners!

So, what is it about big corporations that keep people from being entrepreneurial? The answer to this is equal parts structural, financial, and emotional. Structurally, corporations are burdened with bureaucracy. When one has to go through a bureaucracy to get a question answered, purchase something, or to get permission to try almost anything, then by definition that structure will stifle creativity and innovation. Thus, that internal sense of ownership we call entrepreneurship is stifled. While it is true that even entrepreneurs have to ask permission to do things, there is no built-in bureaucracy to inhibit decision making.

Second, financially, corporate types have vast resources and can borrow from stockholders. Entrepreneurs rarely have access to that kind of support, and with the recent economic crisis in the banking system, there are not many entrepreneurs who can even borrow money. While one cannot say that an entrepreneur relishes this lack of financial support, it is certainly a motivator.

This leads to the many emotional burdens placed on the denizen of the corporation. From job security to fear of failure, corporations place emotional burdens on individuals that inhibit them from developing entrepreneurial behaviors. Of course, entrepreneurs have all sorts of other emotional burdens, like paying rent, finding new work, putting up with the neuroses of one's partners, and begging at the knee of a banker—minor things like their very survival.

Entrepreneurs must also have knowledge and “know how” about every aspect of their business from product to finance to PR. It is absolutely essential to know how all these business activities contribute to the creation of a successful product to be a successful innovator. The corporate structure does not lend itself to this kind of holistic approach.

As much as we would like to think that it's possible for a corporation to facilitate ownership/entrepreneurial thinking, one cannot be overly optimistic. That's not to say that there aren't examples of entrepreneurial behavior in the corporate world, but these appear to be the exception rather than the rule. Those blessed (or cursed) with an entrepreneurial bent are often the individuals in an organization who want to exercise that freedom on their own. They are often the top performers who charge forward, show great promise, but become demoralized by all of the things that are required within large corporations to accomplish the tasks of production and getting things to market. They are the ones who, when asked, never see themselves as working for the company, but rather believe it's better to work with a company. At the first opportunity, these individuals often jump at the chance to go out on their own.

Some large firms are able to facilitate entrepreneurship within their walls, too. There is at least one example of a company that is able to do both, find companies with important technology and nurture them without smothering them and spinning off companies that are founded on internal technology; that company is Shell, which is one of the largest explorers for and producers of oil in the world.

10.5 How to Build Entrepreneurship within a Large Corporation

We should address here the working conditions that companies can set up to encourage entrepreneurship, or what is now being called intrapreneurship, within an organization. The most enduring—and certainly most beloved—story of intrapreneurship is Lockheed Martin's Advanced Development Programs, also known as Skunk Works, and its founder Kelly Johnson. Besides creating many of the world's most innovative aircraft, including the SR71 Blackbird, Johnson set the standard for what an intrapreneurial organization should look like. He operated Skunk Works as an autonomous organization within Lockheed, which meant having his own accountants under his control, writing his own contracts, choosing what work he did and for whom, streamlining purchasing to get parts and supplies when needed rather than from the lowest bidder, and adding an unparalleled engineering staff that worked hand-in-hand with the mechanics who built the aircraft.

First, Skunk Works was, for all practical purposes, an autonomous organization. Lockheed management was smart enough in spite of their constant anxiety to allow Johnson to set up Skunk Works and leave him alone. One can be sure there was a certain amount of handwringing inside upper management, as well as a desire to stick their noses into the operations of that division, but they were smart enough to realize that Johnson would not tolerate interference from them. He was successfully delivering product to his customers that would've been impossible without him, so it was in their best interest not to provoke him. The lesson: The less upper management involvement, the better.

Second, Johnson had a shoot-the-accountant mentality. By doing the best, most innovative work, Skunk Works made money for Lockheed and created a reputation that holds to this day. They came in under budget and on time on virtually every aircraft they designed and built. They had an absolute understanding of what had been spent and very tight projections on what was left to do, and they lived up to those expectations.

- The Lesson: While financial controls are necessary, an intrapreneurial team is responsible for knowing how to spend the money and when to spend it. This is not to say that the group should be able to spend whatever it wants, but when a budget has been agreed upon, the internal team should be allowed to spend money as needed.

Third, Johnson understood the power of very small, cohesive, co-located teams. Engineers and mechanics were all under one central roof with the design bullpen immediately adjacent to the production floor. This arrangement streamlined the work, allowed for the rapid correction of mistakes, and let everyone's voice be heard, since the mechanics and fabricators often had the best ideas for solving problems. Most importantly, it kept the engineers grounded in reality.

- The Lesson: If you're going to commit to this structure, people assigned to the group should be in one place, both physically and spiritually, dedicated solely to the success of the team. “Virtual innovation” in which individuals who are supposed to be collaborating, can be “remote” is contraindicated. Kelly knew this, as now do Google and Yahoo. In addition, having multiple reporting responsibilities is the kiss of death. Everyone's fate must be tied to the success of the intrapreneurial group and outsiders cannot render proper judgment about one's performance.

- Fourth, the project specifications were set in stone early, and any specification that would not, or could not be adhered to had to be declared and agreed upon by the customer, up front. Johnson understood Charles Kettering's mantra, “A problem well stated is a problem half solved.”

- The Lesson: A company must be absolutely clear about the intrapreneurial team's goals. The more time spent on problem definition, the better the results. Good leadership helps a group develop a clear problem statement, which drives the goal statement and creates a clear and definitive work plan.

Fifth, while I'm not sure that Johnson was a “people genius,” he was a hard driver who didn't suffer fools gladly, especially fools from the U.S. Navy. Johnson ran Skunk Works with his “14 Rules of Management,” which can be summed up by his motto, “Be quick, be quiet, and be on time.” Johnson's 15th, and unwritten, rule regarding the U.S. Navy was spread via word of mouth: “Starve before doing business with the damned Navy. They don't know what the hell they want and will drive you up a wall before they break either your heart or a more exposed part of your anatomy.” Johnson understood that you must encourage people to try, and to not fear failure, but understand that while you may not know every step of the path, you must know exactly where you are going before you start down a path.

In all creative ventures, failure is inevitable. In fact, it's been said that if you don't fail, you're not risking enough. The trick is to first take on the most difficult of the problems that you face. If you solve the easy problems in the beginning, you've wasted a lot of money and time when the toughest problems stump you in the end.

To apply the lessons learned from Johnson and Skunk Works and lead a successful intrapreneurial group, corporate leadership must master the skill of watchful detachment. Watchful detachment describes kind of a state of “nirvana,” unattainable in most corporations, that allows management to watch and monitor without intervention, encouraging intrapreneurs toward risky behavior and understanding that invention does not happen on a schedule. Without creating a firewall of protection around an internal team and its leader, the intrapreneurial group will fail and you will end up losing the group, or the leader, or the product, or all three.

Understand that intrapreneurship has been tried for years with varying degrees of success. Most efforts fail, as do the vast majority of corporate social experiments. They fail because of impatience, lack of support, personality conflicts, lack of a clear mandate, poorly defined goals, and dozens of reasons outside of the control of the company or the group. When they do succeed, it is because they are allowed to define a clear path, are encouraged to be truly autonomous, and are blessed with a strong, credible leader. They know that the leader must have the authority to modify operating rules to suit the project, and be allowed to build a cooperative, collegial team where rewards are based on performance and not on how many people are under his or her supervision. Most importantly, upper management must be able to let go and live the notion of watchful detachment. In those conditions, incredible things can and do happen.

What to Look for in Your OI Partner

Now that you know you have a need for OI, where do you go? There is no simple prescription for this hard question. This is where we re-address problem definition as central to the process of finding a small Open Innovation partner. As mentioned earlier, Charles Kettering said, “A problem well stated is a problem half solved.” This is a pivotal concept that must be reemphasized. Most organizations actually misattribute the root of their problems. Truly understanding the problem statement and need driving the problem is the key to understanding what your OI needs are and how best to facilitate moving forward to solve those problems. The first step is to know what your problem is—where does your Open Innovation need reside? This could be anything from having the need to get your organization to think outside the box, which might lend itself to a small consulting company for ideation facilitation, or it could be along the lines of seeing what others are doing in a similar arena, in which case you might use a crowdsourced platform. Only when you have defined or have a firm idea of where your Open Innovation initiative lies can you begin to look for the right OI partner.

- Small Consulting Firms. These are the original Open Innovation providers. The functions provided can range from ideation facilitation to helping create the organization structure needed for the innovation initiative. This can also include engineering houses, Industrial Design firms, and prototype houses. When dealing with these small organizations most people look for references, third-party verification, or anecdotal experiences. These last are a great way to connect with smaller firms that just don't have the visibility that larger consulting firms have. Many of these businesses are introduced via a colleague. Asking colleagues and acquaintances for referrals can help immensely when looking for help. Another place to look for external partners is at conferences: Whether they are represented or not, many of the people in attendance are able to share their experiences and contacts. Networking is a great tool when looking for the right fit in any OI or innovation initiative.

- Universities. Most universities are used for scientific research. Scientific, or applied, research may be an important component in some NPD projects, but there is often a huge gap between university research and successful commercialization. In the past, most universities have not focused as much on applied science. Most university faculty, because of the incentive structure of “publish or perish,” are more apt to be engaged in fundamental research rather than applied research, although this too is changing. In addition, most academic researchers understand the need for commercial success, but because of the huge gap between idea and commercialization most still struggle with this aspect. Then there is the Intellectual Property (IP) “issue.” Experienced universities understand that most corporate entities or venture capital divisions don't want to deal with the university legal department (at least not for long), and know when to bow out or take a back seat in order to move the project/product forward. This is not the case with the smaller universities who often overvalue the importance of the IP, the 1 percent inspiration, as Edison called it, but undervalue the importance of the 99 percent perspiration, the commercialization that it takes to get the IP to market in a profitable way.

- When selecting a university partner, make sure to work with universities that don't want to keep the IP to themselves and know that the value of IP without commercialization is worthless. Look for universities that have experience in the commercialization sector with a successful track record.

- Crowdsourcing. The idea behind crowdsourcing is that you can enable innovation by enlisting the services of a number of people, either paid or unpaid, typically via the Internet to solve your problem. This can be harder to utilize because of the nature of the relationships it involves. For our definition, crowdsourcing is good for ideas but not as helpful on the execution side. It does allow for a very wide net to be cast in order to understand what others (individuals and companies) are working on and how it might be applied to your solution. Intellectual Property has always been a major issue when it comes to crowdsourcing. Most platform-based crowdsourcing ask that the inventor/submitter sign the IP over to the larger organization. There are companies that can facilitate this well, but most people or organizations that may have the answer to the problem do not want to participate in crowdsourcing because of the difficulty in valuing specialized knowledge and the IP that such knowledge can lead to when presented with a problem in the center of one's “solution space.” Many people embrace the idea of opportunity and that it's better to have a small piece of something big versus a big piece of something small, but most innovators and experts realize that their knowledge is worth more than the average challenge payout.

- When working in the crowdsourcing arena, remember that the execution side is just as important as the idea part. Find resources that have successes that they can point to and have helped facilitate on both the front end and back end of the innovation process.

- Portals. Many larger organizations have been forced into the portal adoption of Open Innovation due to Intellectual Property protection and trying to mitigate loss of the IP, sometimes referred to as IP contamination. There are two ways organizations are using portal systems—submit an idea, which means if you have a great idea, send it in, and submit an idea for an RFP, which is represented by an organization that has a need for which they would like outsiders to participate in. There are pros and cons to this. Clorox was an early adopter of the portal system, which allowed for them to protect against IP contamination while engaging their customers. Procter and Gamble's Connect and Develop is also a well-documented case for Open Innovation portal use.

- When implementing a portal for OI within an organization it's important to remember what the goals are when developing. Some organizations are simply looking for IP protection while others are actively engaging their audience. There are organizations that only build a portal for internal uses, which can also be very beneficial. This can allow for engagement of employees that may not normally have the opportunity to share ideas on innovation. The goal should always be well stated so that the development can fall in line for a successful launch.

- Partnership with Small Companies (“Network of Experts”). Most large entities look to their already established vendor list to help move technologies forward. There is often a certain amount of trust needed in order to even begin the innovation conversation. Since the relationship and the trust are already established, many of the uncertainties in initiating and closing an OI agreement are already known. By utilizing a known supplier or a trusted expert, the cost and the timeline to engage the OI partner can be reduced.

- Another way to seek a “network of experts” is to seek references from trusted colleagues with whom you have worked throughout your career. Ask contacts on LinkedIn and other professional sites that can offer sound advice on who they have used in the past or are presently collaborating with. Another place to seek help, advice, and recommendations are conferences. Conferences are typically full of great opportunities to ask questions of presenters and most of the time service providers. Never underestimate the power of a face-to-face meeting with a potential service provider; one can learn a tremendous amount about the knowledge of a provider and outcomes.

10.6 Why Working With Small Companies Is Important

Technology advances at far too fast a pace today to keep up with everything. Large organizations need to constantly seek help and expertise outside their own walls to stay competitive. No one entity has the means to know everything about the world of technology, but by having the right resources and right network of experts, organizations have a much easier time keeping up with the important advancements in technology. At the same time it's not only the technology that is changing but also the customers' needs and wants. Utilizing the external resources and the various experts on the topics and trends can allow for a much clearer picture of the future and in which direction to go. There are many knowledge and technology gaps that larger entities have to fill these days. Utilizing smaller entities to help fill these gaps is imperative in moving innovation initiatives forward.

Best Practices When Working With a Small Company

Small companies are usually engaged in efforts that can positively affect the large company's bottom line, and the value of that should be recognized by the large company by providing:

- Special and or flexible contracts and payment terms. Small companies don't have the resources to be represented in the same manner as the large corporations. They don't usually have large legal or accounting departments. Make the contract process clear to the small business from the outset with timeline projections and the explanation of standard contract terms. Take the time to get feedback, answer questions, and be flexible enough to have the contract work for the small company also. Be flexible with contract terms and especially payment terms. Small companies don't usually have the cash for protracted payment cycles.

- In fact, scholars assert that, “One of the main reasons often cited by CIO for failing to achieve innovation in outsourcing is the uncertainty about the nature of innovation desired from the vendor, and also the inability to design a contract that is on the one hand mitigating a client's exposure to be exploited by the vendor and at the same time offers compensation for extra work and innovation by the vendor. Put simply, most outsourcing contracts do not accommodate these often contradicting requirements properly.”

Frequently, there is a disconnect between R&D managers who outsource work to small companies and the legal and purchasing branches of a large corporation. We have the experience of dealing with such a client—a very large Fortune 500 company. Their corporate legal and purchasing departments are not in any way in sync with the needs of the R&D team charged with finding and applying innovation. Any outside contractor must go through a process of creating a Statement of Work (SOW), which must be approved by a legal team. The legal team review can take from four to six weeks. From approval and signatures on the SOW, the legal team passes it to the Purchasing Department for purchase order creation, which can take another six weeks. This whole process slows down innovation momentum and keeps the small business guessing as to when the project kickoff can commence. Human resources that the small business had allocated for the project may not be available at the moment when the purchase order is finally issued. This puts the small business in the position of starting the project on faith and not being able to invoice for up to two months or waiting until the purchase order is actually in place and hoping that the resources are still available to work on the project. This is a situation where the Fortune 500 company has not adapted its corporate structure to support the R&D team and the innovation cycles reflective of a smaller, quicker innovation supplier which was the main point of attraction in the first place.

- In fact, scholars assert that, “One of the main reasons often cited by CIO for failing to achieve innovation in outsourcing is the uncertainty about the nature of innovation desired from the vendor, and also the inability to design a contract that is on the one hand mitigating a client's exposure to be exploited by the vendor and at the same time offers compensation for extra work and innovation by the vendor. Put simply, most outsourcing contracts do not accommodate these often contradicting requirements properly.”

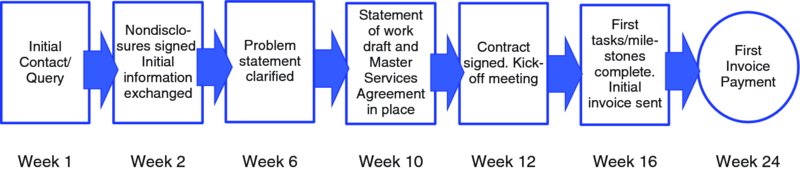

- Figure 10.1 illustrates the amount of time it can take to go from initial engagement or query to payment (most companies are going to 60-day net payment terms). This cycle can be six months or longer (as is the case described of the Fortune 500 company). Rarely does the small company have the luxury of having staff available or the cash to carry a project for such a protracted period of time. Refer again to Figure 10.1.

Figure 10.1: Average Time for a Small Innovation Provider to Receive Payment from a Large Corporate Entity

- Identify a corporate champion and/or project manager within the large organization to work with the small entity. Having an internal person who is the single point of contact ensures continuity and clarity of communication between the entities. Corporations often move employees around through promotion or reorganization, so it is important to hand the project baton to someone somewhat familiar with the small company and the project if the initially assigned internal champion moves to a new position.

- The corporate champion should have access to the company hierarchy to smooth out any hurdles the small company may encounter in working with the large company. This might include troubleshooting issues with timely invoice payments or approvals on next phase contracts.

- Provide a collaborative work environment. Schedule regular communication with the small business partner to track project progress and give feedback. Support the work of the small company by providing quick and clear responses regarding questions and data. Clear goals and a concise problem statement are also extremely important. Collaborate on solutions to any project hurdles or unforeseen problems.

- Treat the small company as an important partner. Recognize their work. Being publicly identified as a partner can sometimes mean as much as the money that is exchanged between the two. Most small companies do not mind being the “man behind the curtain” as long as there is support for the work, a collaborative environment, and the eventual recognition. One of the most valuable methods of recognizing the small company is by providing testimonials for advertising and public relations efforts and referring and recommending the small company to new customers. There is no better way to declare a small company's value than to provide a referral or testimonial.

10.7 Conclusion

Without the proper mindset, understanding of goals and organizational buy-in, Open Innovation becomes just another buzzword without much support or outcome befitting the concept. The world of Open Innovation is open and ripe for utilization if one can structure the organization in a manner that is supportive and nurturing. There are a multitude of opportunities for partnership, co-development, and collaboration to help move products to market faster. That's the goal of Open Innovation in New Product Development after all—to create superior value in an organization.

Takeaways

- Establish definition of goal(s) and desired outcome of Open Innovation initiatives from the beginning. Strategy is important and understanding why you are moving forward with OI is important for internal buy-in. Establish the culture and mindset that a collaborative team is good and allows for more opportunity.

- Make sure your OI endeavors match the capability and strengths of your OI partner.

- Treat your OI provider as a valuable asset. OI partners should be treated as equals, not solely as service providers. Their value comes from their ability to move quickly and deliver faster on the innovation initiatives.

- Make sure you have flexibility to work with your preferred OI partner. Realize that there is not a one-size-fits-all model for OI. What works for one company will not be a perfect fit for another, no matter how similar the organizations might seem.

- Continuity within the large organization, from phase to phase, is important. Knowing or engaging the next “baton holder” before the next phase is important for a smooth transition without long-term hiccups.

- Over-communication is a good thing in Open Innovation. Making sure the problem definition is understood by all involved parties, will make for a much smoother process, relationship, and outcome of final product.

- Make sure you realize that Open Innovation, with an external partner, as in the case of an internal development effort, can be complex and messy. This is just the nature of innovation on the whole.

- Finding the right partner for OI initiatives will allow you to move faster and have opportunities that may not have been possible before. This will open new doors for all your innovation needs.

References

- Atkins, R., and Steward, L., 2013, Restoring America's Lagging investment in Capital Goods, Information Technology and Innovation Foundation

- Chesbrough, Dr. Henry, 2003, Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology, Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation, Boston, Massachusetts

- “Dictionary definition of bleeding edge,” technopedia.com, retrieved January 20, 2014.

- OShri, Dr. Ilan, and Dr. Julia Kotlarsky, 2012, “Innovation in Outsourcing: A Study on Client Expectations and Commitment,” Warwick Business School and Rotterdam School of Management.

About the Contributors

- Mike Rainone is Chief Innovation Officer at PCDworks, a multidisciplinary Innovation and R&D company. Mike has over 25 years of experience working in the world of Innovation and NPD. Mike has a broad knowledge of emerging technologies coupled with a strong background in psychology and design. He has taught architecture, industrial design, and business, and has developed products for clients as diverse as Sunbeam, Avery Denison, 3M, and Kimberly Clark. Mike has an M. Arch from the University of Texas at Austin, and an MA in Psychology from the University of North Texas. Mike is also an award-winning columnist and the author of a recently released book of compiled articles entitled, “Looking into the Eyes of a Dinosaur, The Evolution of Innovation and Finding a Path to the Future.”

- Donna Rainone, President of PCDworks, has helped grow an organization built on the idea that the execution side of New Product Development is just as important as the Front End of Innovation. Donna was part of the dynamic team that helped build the 77-acre PCDworks innovation campus that houses seven scientific and instrumentation testing facilities, offering one of the largest combinations of onsite engineering and analysis laboratories available in a single location. Donna as honed her design and management skills working as an architect on multi-million-dollar healthcare facilities. She has a graduate degree in architecture, and her work has been featured in several publications, including AIA Architect magazine. Donna has an M. Arch from the University of Texas at Austin. Donna's other title when at the PCDworks innovation campus is “resident den mother,” where she keeps up with her campus full of engineers and scientist.

- Louise Musial is Vice President of Business Development at PCDworks, where she continues to build the company brand and connect the dots between engineering, Open Innovation, and industry trends. She has authored numerous articles for technical magazines, is a regular contributor to Product Design and Development (PD&D) magazine, and recently hosted a 20-episode web series on up-and-coming innovative companies. Musial also lectures regularly on the topics of Innovation, Open Innovation, and business trends in R&D. In addition, she sits on the board of PCDworks and Backcountry Medical Guides.