By Bob Tomaine

Recognizing a Ford V-8 is pretty simple, unless it happens to be an 1,100-cubic-inch model that puts out 500 horsepower in stock form.

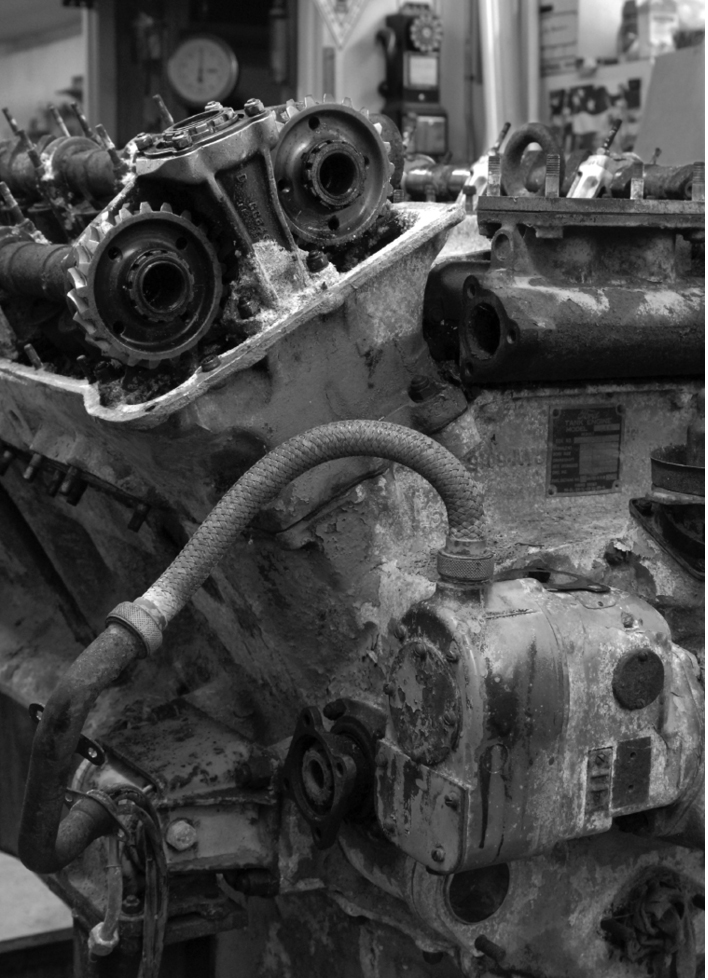

“It’s actually double-overhead-cam for each head,” said Bob Rubino, owner of Mil-Spec Vehicle Restorations in Belvidere, N.J. “It’s four cams and 32 valves, four valves per cylinder.”

“It’s a huge motor for the day,” said Jim Knerr, who rebuilt the Ford GAA at Mil-Spec. “I like to tell people that nowadays they can make a 500-cubic-inch motor with 1,000 horsepower.”

The GAA’s day was in World War II, and its roots are in aviation.

“Ford made an experimental V-12 aircraft engine,” Rubino said, “and this was adapted from that. The aircraft engine never made it into production, but when they needed a tank engine, this is what they came up with.”

Mil-Spec’s Jim Knerr reassembles the Bendix-Stromberg NA-Y5G carburetor, which is a much larger than what would’ve been on an everyday Ford V-8 of the time.

The Sherman tank, he noted, was designed for a radial engine with high horsepower and air-cooling, but radials were needed for aircraft, and that limited the number that could be produced for tanks. Ford’s GAA was one of several automotive engines to fill the void, and Rubino said that it ended up as the one with which the Army was most pleased.

“It’s got low-end torque, which you want, and it’s got snap,” he explained. “The radials are dogs. They’re not putting out power until they’re up against the governor.”

Based on serial numbers, more than 20,000 were produced, he said, and the one shown here came from a donor tank.

“It was a monument that we were able to strip for parts,” Rubino said. “That was an M4 A3 Sherman. It’s going in an M36 tank destroyer, which is basically Sherman running gear, but the hull is different. They were built late in the war.”

The M36’s early history is hazy, as it was obviously rebuilt from an earlier M10 tank destroyer that was probably a Ford. Its later history, though, is known.

“After the war,” Rubino said, “it was given to Yugoslavia as part of mutual defense aid. In the early 1950s, Yugoslavia eventually turned Communist and their aid from the United States ran out along with their spare parts for the GAAs. I’m assuming that, because all of these Ford engines were taken out and Russian tank engines out of T55s were put in.

“In 1997, a fellow named Bob Fleming in England brokered a deal to have a bunch of these tanks. The Bosnians were using them in their civil war in the ’90s and when NATO went in and the peace accord was struck, the tanks were slated for destruction. There is only a handful that came to the United States. I was on the dock in Liverpool when the first batch came in. Some of them still had the artillery ammunition — the ammunition for the main gun — in them.”

Rubino helped unload them and the M36 into which the GAA will be placed was among them. It went to southeastern Pennsylvania where it was cosmetically restored and then sold to a collector in New England. By that time, Rubino had started Mil-Spec and completed other restorations for the M36’s new owner. When he completed a Sherman late last year, the truck that delivered it returned with the M36.

He said the M36 was in good condition and had probably been stored mostly indoors between World War II and the war in Yugoslavia. He expected to find mechanical problems, because of the combination of the more powerful Russian engine and the original driveline components, but everything had held up well.

“So this restoration project involves us putting the proper engine back in,” Rubino explained, “which is a lot more than just the engine.

“The entire wiring system’s got to be changed, the fire suppression system, the hull bulkhead. We had to get another bulkhead, we had to get new fan drives, we probably spent more time modifying the hull — putting the hull back to its proper configuration — than rebuilding the engine.”

The GAA didn’t receive any upgrades during the rebuild, because it didn’t need them, thanks to the engineering that went into it.

“I don’t think anything was ‘because we can,’” Rubino said, “because it was the government, always going for the lowest bidder. I think it was just an aircraft mentality and I think, too, that 500 horsepower in 1942 might as well have been a jet turbine engine. They didn’t know how to build an engine that could handle that kind of power, so they know they’ve got this massive amount of power and they’ve got to be able to harness it without the engine blowing apart.

“Everything on that is on needle bearings. The throttle shafts for the carburetors are on needle bearings. Even the fingers on the clutch pressure plate are on needle bearings.”

“The thing about the engine is that it’s of a higher quality than most of the engines from back then, because it was aviation thinking more than anything else,” Knerr said. “High-quality materials. You have a cast-steel crank whereas others might be forged. There’s stuff in that engine that you see today as ‘modern’ in racing. The wrist pin design came out in the ’80s and they were saying it was a revolutionary design. It’s the old what-was-old-comes-around-to-new, but they use modern materials to make it even better.

Even a Ford fan more knowledgeable than most would be unlikely to recognize the GAA as a Ford V-8.

“The whole engine assembly was balanced. There’s a spec in the book that all of the rods have to be within three grams. The rod-and-piston assemblies weigh 10 lbs. each.”

The engine was complete when it arrived at Mil-Spec, Knerr said, and the fact that it was inside of a tank had provided some protection over the years. Still, several GAAs were disassembled to ensure that he had the parts necessary to rebuild it, and new cylinder sleeves were machined based on Ford drawings.

Rubino said that the GAA isn’t known for any chronic weaknesses.

“The only real problem with them — and this is something we’re probably going to have to address in the future with more modern parts — is the spark plugs,” he said. “They foul like you can’t believe and each time you clean them, you get less and less time between services. Almost 20 years ago, we could still get them from Champion and they were over $75 a plug. I don’t know whether you can get them today, and I can only imagine what they’d cost. On this one, we were lucky. I had brand new old stock plugs for it.”

The WWII-era M36 was developed to provide the military with a more heavily armed tank destroyer to deal with increasingly heavy German armor. It was armed with a 90mm gun and an open-topped turret.

The NOS plugs were fine and the engine started on the stand on its first try. It’s been test-run several times since and Rubino recalled the first time he’d rebuilt a GAA.

“I got it started,” he said. “It was running really nice for probably not more than 10 minutes and then it died. I spent the next half-day looking for the problem, only to find out that the jerry can was empty.

“How much gas does it take to feed 1,100 cubic inches? I know from our experience that this particular engine in a test stand is going through a gallon every three minutes.”

Bob Rubino, owner of Mil-Spec Vehicle Restorations, checks temperatures during a test run of the GAA.

GAAs have been used in tractor-pulling and Knerr said he’s seen photos of them in road vehicles, but he’s never seen one running. Rubino spoke of a tractor whose GAA suffered a block-explosion during a pull, so fuel economy might not be the only consideration.

Whether it’s a realistic engine for a vehicle today is thus open to debate, but the point is that the GAA did its job as intended. Rubino emphasized that its precision design didn’t prevent it from holding up, even though a long service life wasn’t the highest priority for a weapon.

“The whole thing was expendable,” he said, “and yet it was built as something that could be rebuilt forever.”