The Smalls reef is an extensive jumble of rocks spread over several miles at the entrance to St George’s Channel. Most of reef lies just below the waves and its lighthouse sits on one of the two biggest rocks.

(Author)

The Smalls reef is an extensive jumble of rocks spread over several miles at the entrance to St George’s Channel. Most of reef lies just below the waves and its lighthouse sits on one of the two biggest rocks.

(Author)

THE WILD coastline of Wales has claimed many fine ships which failed to accurately negotiate the innumerable hazards that bedevil the water around this historic kingdom. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that for the subject of this chapter we remain in Celtic waters. In the south western corner of Wales, the old county of Pembrokeshire offers breathtaking scenery. It is an area of contrast; towering sandstone and limestone cliffs rise from azure waters, while jagged promontories enclose wide sandy beaches. Seabirds, notably thousands upon thousands of fulmars, guillemots and razorbills, are drawn to this temperate corner, where they nest undisturbed on the narrowest cliff ledges or offshore islands, both blanketed with a lush carpet of colour during the spring and summer months. Much of this glorious coastline is part of the Pembrokeshire Coast National Park, ensuring the conservation of its attractions for future generations, despite the recent encroachment into Milford Haven by rows of oil storage tanks, jetties and a handful of oil refineries which despoil this huge inlet, once described as, “the finest natural harbour in the world.”

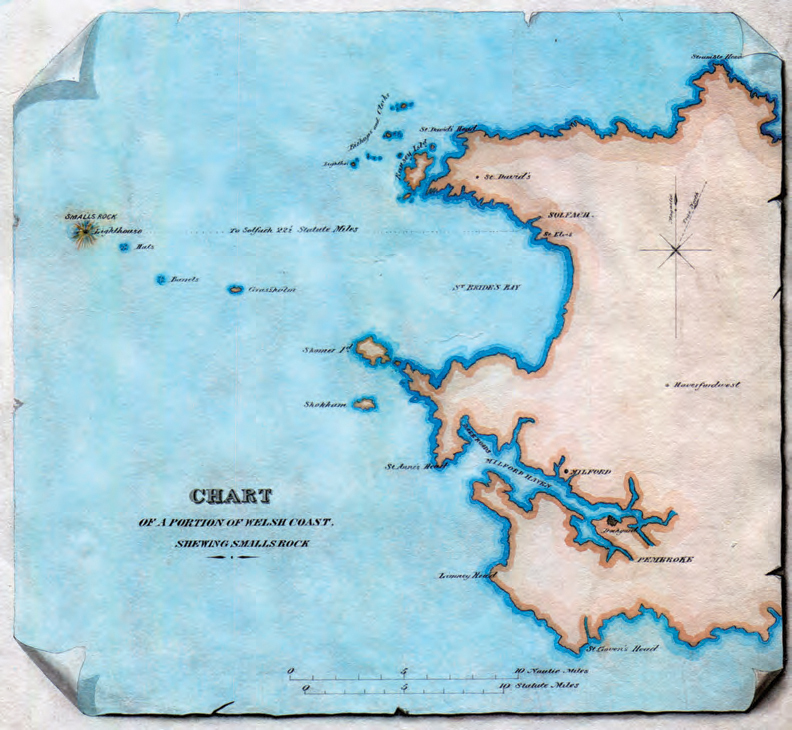

A hand-coloured Trinity House plan showing the location of the Smalls lighthouse in relation to the Pembrokeshire coast.

(Trinity House)

This rugged coastal scenery marks the westernmost extremity of Wales. Travel further west and the next landfall is the southern coast of Ireland. As the fertile soils of Pembrokeshire plunge into the sea it is with some reluctance that this wild landscape takes its final bow. Stretching seaward from St Ann’s Head for over 20 miles is a string of islands, each a barren, windswept refuge for multitudes of seabirds, the final remnant of a Celtic landscape struggling to hold its own above the waters of St George’s Channel. First comes Skokholm, then Skomer, both much beloved by ornithologists, beyond which rises the rounded profile of tiny Grassholm with its thriving gannetry. Next in the chain are two lonely clumps, 2½ miles apart, that barely struggle above low water, known as the Hats and Barrels reefs. Finally, 21 miles from the nearest land, is a tiny cluster of rocks known collectively as the Smalls, the setting for this chapter and the site of a lighthouse that boasts the dubious distinction of being the most remote station under the jurisdiction of Trinity House.

Imagine, if you can, the sheer isolation of this lighthouse – over 20 miles from the nearest Pembrokeshire cliffs and even further from any sizeable settlement. Completely uninhabited, these 20 jagged rocks are assailed from all points of the compass with unequalled ferocity by wind and wave. They are over twice the distance the Eddystone is from Rame Head, and break the surface over a distance of 2 miles at the entrance to St George’s Channel, straddling the path of the busy seaway through the Irish Sea to Liverpool. There can be few more Godforsaken sites around our entire coastline. The fact that these rocks lie in one of the busiest sea routes in the North Atlantic only serves to underline the malevolence of the reef. Rising to 12 ft above high spring tides, they provided a reasonable landmark in clear, calm weather, yet when Atlantic swells over-topped these obdurate clumps the foaming swirl of broken water was the only clue to the whereabouts of this hidden menace.

There have been two lighthouse placed upon the Smalls; the original was the setting for one of our classic lighthouse sagas, events which have been immortalised by various sources and have passed into the folklore of this corner of Pembrokeshire. I make no apologies for retelling it here, but first, some background to the origins of this historic structure would be in order. Again we must look to the 18th century when the Smalls were owned by John Phillips, a Welshman and native of Cardiganshire, who was appointed manager of Liverpool’s North Dock in 1770. Why anyone would want to ‘own’ a series of wave-lashed lumps of rock in the middle of the Irish Sea has never been fully explained. Whatever the reasons, Phillips owned the Smalls reef. He had watched the construction of lighthouses and beacons around the expanding port with interest, and was naturally keen to mark his own personal reef in some way similar. Unfortunately being plagued with near bankruptcy he was not particularly well placed to push his creditors for finance. The events of a winter’s night in 1773 spurred him into action.

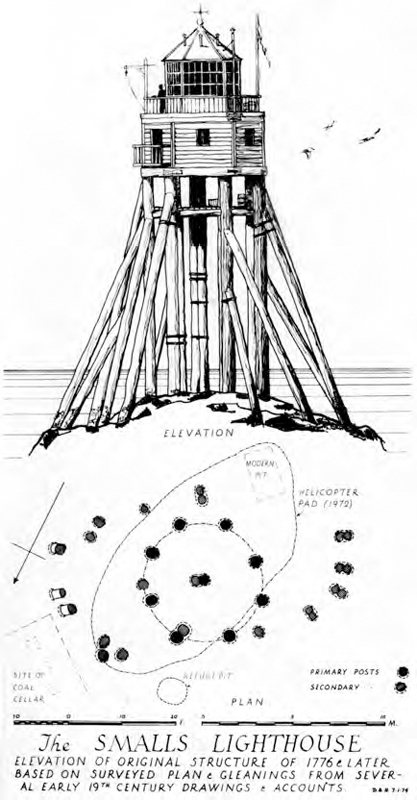

An extremely accurate drawing by Douglas Hague of what Whiteside’s lighthouse would have looked like after many extra oak struts had been added to strengthen the original nine.

(D. B. Hague)

During a wild night late in that year, the clipper Pennsylvania of 1,000 tons was caught in the grip of a tearing gale as she voyaged from Philadelphia to Bristol. After a peaceful Atlantic crossing the seas had suddenly been whipped into a frenzy by a storm which tore at the very heart of the vessel as she pitched helplessly in the heaving swell. Only a handful of miles from her destination, the mountainous waters dwarfed the tall-masted ship which was picked up like driftwood and hurled on to the largest rock of the Smalls. For a week afterwards the stark reminders of the tragedy were washed ashore in tranquil Pembrokeshire bays; timbers, rigging, shredded sails, and the corpses of a few of the 75 souls who had perished on the reef. Enough was enough. Phillips, reputedly a passenger on the ill-fated vessel, was not insensitive to the public clamour and vowed to mark in some way his own personal maritime graveyard.

‘The Intrepid and The Smalls’ is a vivid watercolour by the artist Simon Swinfield of Solva of what Whiteside’s lighthouse might have looked like in the days of sail.

(Simon Swinfield)

With an air of bravado he boasted of his intention to build a lighthouse, “...of so singular a construction as to be known from all others in the world as well as by night as by day.” Further, more precise, details of his “great and holy good to serve and save humanity” were still somewhat vague, yet this advance publicity obviously had some effect. On 4th August 1774 the Treasury granted him a lease to erect a beacon on the Smalls rock. Plans were now invited and closely scrutinised by Phillips who eventually settled on the design from a 26 year old man called Henry Whiteside. Following the contemporary trend in lighthouse construction, Whiteside had no previous experience in the field but was engaged in the unlikely profession of “a maker of violins, spinettes and upright harpsichords”, although he had undergone training in wood carving. Exactly how these almost absurd qualifications got him the job isn’t certain, yet there is no dispute over the fact that Whiteside planned and built a beacon of wood which subsequently stood for well over three-quarters of a century on that miserable outpost of civilisation.

His design was unique. There had never existed a lighthouse of such a curious form before, and there was never another built in the mould of the original. In essence, Whiteside raised an octagonal wooden structure, crowned by a lantern, on sets of oaken stilts. The house was 15 ft in diameter and divided into two sections, one above the other. The lower served as sleeping and living accommodation while over this, and connected to it by a trap door, rested the lantern room, surrounded on the outside by a gallery. Beneath the living quarters there was also a kind of landing, open to the elements, on to which casks and boxes of non-perishable goods could be lashed. Windows were let into several of the sleeping quarter walls, so too was a door which led to the outside balcony for “...keeping bad weather watch, and also to keep the windows of the lantern clean and polished bright.” Several chimneys projected through the roof of the lantern house to conduct away candle smoke, and the balcony was fitted with the obligatory flagpole and crane hoist. A rather ungracious account once described the structure as a “strange wooden-legged Malay-looking barracoon of a building.” (A barracoon was a stilted enclosure used for storing slaves on the west coast of Africa prior to their sale.)

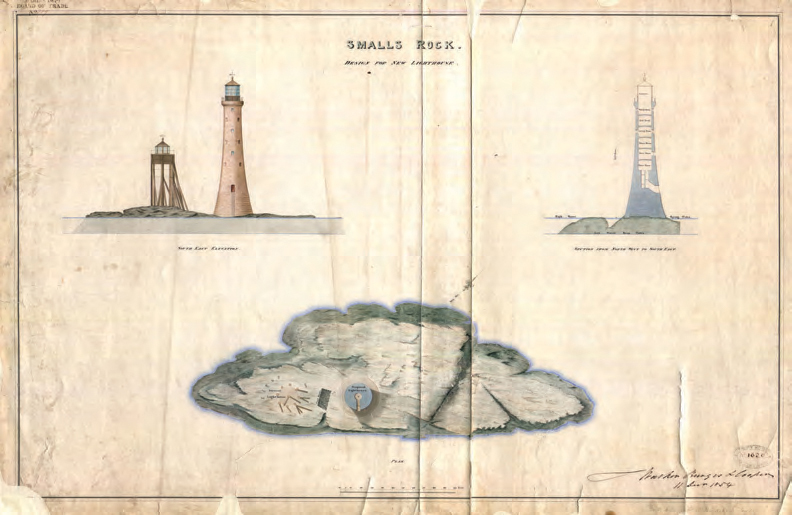

On a plan dated December 1854 called ‘Design for New Lighthouse’ we can clearly see a comparison of Whiteside’s wooden light and the masonry tower that James Walker designed and James Douglass built. (courtesy of Trinity House)

Although of unusual appearance it was not a design of pure fancy. Whiteside argued that instead of resisting the force of the waves, his plans would allow the greatest weight of water to pass through the supporting piles unhindered, as these would offer little resistance. His logical and practical design clearly impressed Phillips. By June 1775 he had amassed sufficient funds for materials to be purchased and a start made. A later newspaper report of 1899 made the following observation: “His undertaking was a sudden transition from the sweet and harmonious sounds of his own instruments, to the rough surging of the Atlantic wave, and the discordant howling of the maddened hurricane; and from the fastening of a delicately formed fiddle, to the fixing of giant oaken-pillars in a rock as hard as adamant!”

Although the Smalls were such a vast distance from land, Whiteside did not adopt the procedure of lodging in a nearby floating barrack which was later to become standard practice at isolated lighthouse sites. Instead, he established a base at Solva (sometimes referred to as Solfach on early maps), a tiny fishing village nestling in a sheltered creek over 22 miles from the Smalls. It would be difficult enough to build anything on these venomous humps, but Whiteside certainly was not making his task any easier by necessitating such a lengthy row before a landing could even be attempted. Often it was impossible and the work party had to return without lifting a tool.

Soon after mid-June 1775 he left for the rock in a cutter, accompanied by a gang of rugged Cornishmen, eight miners, one blacksmith and two labourers. They lost much time during this first visit when “...the sea being turbulent, and a gale of wind coming on suddenly...” caused the boat to lose its moorings. They did have time, however, to choose the largest islet of the group “...always above the water, about the bigness of a long-boat,” as the site for the new lighthouse.

Things went badly for Whiteside and his artificers during the early days. On their very first landing, while the men set about excavating the holes for the wooden piles, the winds freshened and the sea began to break over the rock. The cutter rode uneasily at anchor half a mile away and soon had to cast off to run for the open sea when the storm freshened further, giving no time for the work party to be brought aboard. The gale turned the sea into a boiling fury, preventing the boat’s return for two whole days. When conditions had moderated sufficiently for an approach to be made, the crew found the gang of luckless, yet fortunate men gripping a solitary iron rod they had managed to drive deep into the heart of the reef before the storm. For two days they had survived, without food or drink, clinging to a solitary post with numbed hands while huge seas broke over them. This was a forceful reminder of the perilous nature of their task, yet Whiteside and his gallant Cornishmen were made of stern stuff and stuck at their work doggedly.

By early October the weather was deteriorating, forcing a halt to the proceedings. In the four and a half months they had been active, only nine whole days had been spent on the rock. During this time a hole 18 ins deep had been sunk for the central pillar, a second hole started, the positions of the remaining piles marked, and a hut to house 12 men for a fortnight put up. It had not been easy; from the outset the elements had resisted many of their attempts to land, the long and frequently abortive journeys from Solva were both exhausting and dispiriting. Working conditions were positively evil, at the mercy of wind and wave, struggling to keep upright, while at the same time swinging heavy implements. It was reported that:

Probably a 1960s’ view of the Smalls lighthouse showing the interesting lantern roof fixtures and fittings – all of which were removed when its helideck was fitted a decade later.

(Ken Davies)

...the clothes of the workmen were often washed off in shreds from their bodies, and their skins were severely lacerated by falling heavily on the pointed surface of the rock. The workmen, on such occasions, could only save their lives by lashing themselves to the iron bars and ring bolts secured in the rock for that purpose.

During the winter Whiteside erected the whole structure in a field at the top of Solva harbour. This was a particularly fortunate piece of foresight as the original design called for the building to be supported on nine cast-iron stanchions of sectional construction. Upon completion, these proved to be weak at the joints and therefore unsatisfactory. Whiteside amended his plans and substituted oak for metal, a change which necessitated an extensive search through the forests of Wales for specimens of suitable length and straightness. The wooden legs raised the living quarters and lantern to 65 ft above the level of the rock. They were arranged in a circle around the central pillar spanning 40 ft, with individual diameters of about 2 ft.

Work was resumed in the spring of 1776 and, thanks to his diligence during the winter, little trouble was experienced in consolidating the structure on the Smalls. In fact, so speedy was the construction, it was complete by the end of August and lit on the first day of September. It became immediately distinctive because the lantern, containing four lamps with glass reflectors, showed two colours – the main fixed white light, visible for 12 miles, was topped by a less powerful green beam which was only visible at short range and from certain directions. This, no doubt, was Whiteside’s attempt to mark the passage between the two clumps of rocks, although any vessel taking this course was surely tempting fate. Before the jubilant gang of Cornishmen deserted the rock for good, a cellar and store, 10 ft by 6 ft by 6 ft, was hewn out of the rock for the storage of certain weighty commodities such as the drinking water or 12 tons of coal consumed annually which would be impractical to store in the beacon.

The Smalls were at last lit by a lighthouse which could quite rightly justify Phillips’ claim to be “of so singular a construction as to be known from all others in the world.” Its stilted form and bi-coloured lantern made it unique. In rough weather the Atlantic broke against the rock and rolled through the legs of the structure before returning to a foaming sea. The waves were ruthless in their treatment of the beacon. Such an exposed site is regularly subjected to mountainous seas crashing against the unyielding rock. By December 1776, under four months after it came into service, the situation on the Smalls was far from good. The keepers told how the light swayed drunkenly when hit by large waves, so Whiteside was summoned in order that strengthening could be carried out. Without it the life of his beacon was in serious danger.

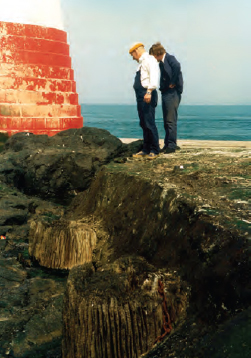

Principal Keeper Terry Cresswell and Assitant Keeper Neil Hargreaves examine what remains of the huge oak stumps from Whiteside’s wooden lighthouse in 1977. Most of the stumps were covered with the slab of concrete seen here when a helipad was constructed on the reef before the tower had a helideck.

(C. J. Foulds)

In January 1777 he, together with his blacksmith, left for the Smalls to effect repairs. These would be further oak piles leant against, and joined to, the existing nine, thus increasing the stability and making the legs more able to resist the lateral force of the waves. While the two men were on the rock one of the almost continuous winter gales blew up, stirring the sea into a frenzy around the solitary wooden refuge. For over two weeks the storm raged, making it impossible for Whiteside to leave the lighthouse. There were normally only two keepers on duty, but with the two extra inhabitants supplies quickly dwindled. It was not long before the situation became desperate. The only method of communication with the mainland was by boat. The weather prevented use of this so Whiteside took action that has now come to feature heavily in tales of desert island ‘castaways’. He wrote a message, sealed it in a bottle, put this in a wooden cask, and flung it into the sea, leaving fate to do the rest. In fact, he made three identical copies, one of which arrived on Newgale Sands on the Pembrokeshire coast, the second beached itself on the shores of Galway Bay, Ireland, and the last floated in the opposite direction altogether to come ashore near St David’s. On the outside of the cask were the words, ‘Open this and you will find a letter’. Inside was a note addressed to Thomas Williams, John Phillips’ local agent for the light, the contents of which explained the desperate plight of the marooned men:

To Mr Williams,

Smalls, Feb 1st, 1777

Sir. – Being now in a most dangerous and distressed condition upon the Smalls, do hereby trust Providence will bring to your hand this, which prayeth for your immediate assistance to fetch us off the Smalls before the next spring, or we feel we shall perish; our water near all gone, our fire quite gone, and our house in a most melancholy manner. I doubt not but you fetch us off from here as fast as possible; we can be got off at some part of the tide almost any weather. I need not say more, but remain your distressed Humble servant,

HY. WHITESIDE.

A further plea from the two keepers and blacksmith was attached at the bottom:

We were distressed in a gale of wind upon the 13th January, since which have not been able to keep any light; but we could not have kept any light above 16 nights longer for want of oil and candles, which make us murmur and think we are forgotten.

ED. EDWARDS.

GEO. ADAMS.

JNO. PRICE.

We doubt not but that whoever takes up this will be so merciful as to cause it to be sent to Thos Williams, Esq, Trelethin, near St David’s, Wales.

By sheer good fortune it was found by fishermen at almost the exact location it was to be delivered to. At the earliest opportunity a boat was despatched to bring the weary and hungry captives off the Smalls. They all survived and were none the worse for their ordeal, yet this period of constantly appalling weather had taken its toll on the lighthouse.

Further repairs were vital for the safety of the beacon, but John Phillips was again short of capital. The keepers were dismissed and the Smalls once again plunged into darkness while a group of Liverpool businessmen took over Phillips’ interests. As most of their trade came into the city on boats, and a large majority of these passed the Smalls, they wisely saw the need to return the light to service. Influenced by the work Phillips had done in establishing the station in the first place, on 3rd June 1778 he was granted a 99-year lease from the traders at an annual rent of £5, who also advanced monies for the addition of further strengthening struts. By September of the same year a new white light radiated from the Smalls, produced by four 5 ft 6 ins reflectors, once again warning ships of these perilous rocks.

The author descends the dog steps from the entrance door of the lighthouse onto the reef. The massive stepped base of the tower is really impressive from this position.

(Author)

Sometime during the period 1800–1801 an incident took place on the Smalls which had far-reaching effects on the manning of rock stations in the future. There were, as normal, two keepers on duty in the light. Conditions outside were particularly atrocious that winter; continual storms assailed the rock extending the normal duty of one month into a lengthy exile of four months for the two men. The pair of unfortunates were Thomas Griffiths and Thomas Howell, both well known characters in Solva, their home. What these two loved more than anything else was to argue. Every second they were in each other’s company was spent bickering about topics so wide and varied, it was said there was nothing they had not disagreed about. They could empty bars of public houses with the force of their arguments, especially when it looked as though they were coming to blows over something. They never did. However much they raged, the towering Griffiths and middle-aged Howell had never been seen in physical conflict. It was perhaps just as well, for Griffiths would not have had the slightest difficulty in despatching the weaker man. They were now marooned together on the Smalls where they could squabble to their hearts’ content and nobody would have to listen.

An interesting comparison of how the same lighthouse on the Smalls has changed over the years from a plain masonry tower, that was subsequently painted with red and white stripes, and then had a white helideck added, before the stripes were removed and the helideck was painted red.

During their prolonged duty, Griffiths suddenly and unexpectedly died, collapsing in the lantern room and striking his head on a metal stanchion as he fell. Thomas Howell, not wishing to be accused of murdering his companion, did not commit the body to the sea but made instead a shroud for the corpse and installed this in a crude coffin fashioned from a cupboard. This box was then lashed to the rails of the outer gallery in an attempt to lessen the stench from the decaying body. Almost out of his mind with fear, Howell managed to raise a flag of distress and make appropriate entries in the log about his companion’s death. All he could do now was to wait for his long-overdue relief and pray to God that it would not be long in coming.

The storm refused to abate, if anything it got worse, driving the waves high into the air to crash down on the lantern gallery, sending sickening tremors through the creaking house. One monstrous breaker split Griffiths’ coffin in two and tumbled the enshrouded corpse on to the gallery where it rested with one arm caught in the railings. Many times boats set out to relieve the keepers, only to be beaten back by boiling seas. On one occasion a vessel managed to battle near enough to the rocks to notice a man leaning motionless on the gallery next to a flag of distress, his hand waving freely as if trying to attract attention. Upon reporting their findings, some concern was felt for the keepers, yet every night, as punctual as ever, the glow of the lighthouse could be seen from the land. What then, could be the matter on the Smalls?

During a respite in the storm a boat raced out from Milford to snatch off the two men. Only then was the terrible truth realised. In a state of complete exhaustion, near hysteria, and absolute fatigue the solitary keeper had never failed in his duty, tending the lantern for day after miserable day with only the putrefying remains of his colleague for company. His ordeal had affected him so greatly it was said that some of his friends did not recognise him on his return. As the events became known, it was obvious that what the earlier rescue bid had seen was the free hand of the corpse being blown by the wind in a morbid greeting, enticing them to come nearer so that they too might join him in eternity. After the knowledge of this story became widespread it was made standard practice for three keepers to be assigned to isolated lighthouse stations, so that if one keeper should fall ill the light could be maintained by the other two without undue suffering and so prevent a repetition of the Smalls’ tragedy.

Although it performed an admirable function, there was no doubt that Whiteside’s structure suffered much damage during times of storm. The total height of the whole tower was only 72 ft, which made it by no means unassailable for large rollers. The force of water constantly surging around and through the piles made the lantern and living quarters rock giddily, sometimes as much as 9 ins out of perpendicular. Each winter brought a fresh crop of problems and repairs to ensure the continued service of the lighthouse.

A storm of exceptional severity in October 1812 closed the tower until the following spring. Whiteside describes the events of 18th and 19th October in a letter to Robert Stevenson:

...It was a tremendous storm here such as cannot be remembered. The Smalls has now been up 37 years with no damage: only a few panes of glass broke sometimes [sic]. The men suffered very little hardships, only being frightened at the time of the storm. If they had stay’d there long their house would have been somewhat leaky the windows being broken. They had plenty of firing and everything they wish’d for to live upon. One of the men lived there 13 years and they are going there again as soon as it is made tenantable.

Not only did it break windows but the lantern was blown completely off. Remnants of this and the actual planking of the house were washed ashore, and only when this debris was delivered to Whiteside’s door in Solva was he aware that anything was amiss on the Smalls. In fact, the situation was rather more serious than the “somewhat leaky” condition described by Whiteside. The whole building was obviously breaking up. The oak legs were snapping like matchsticks, tearing huge chunks of the floor from the lower room with them as the sea wrenched them from the rock. The breakwater built around the base of these to prevent such a thing happening had been destroyed, probably by a single wave, and the interior of the living quarters was running with water which was cascading in through the gaping holes in the roof and walls. The terrified keepers despatched urgent pleas for assistance in casks, exactly as their forerunners had done earlier, but it was not until 8th November that a boat, the Unity containing Whiteside and Captain Richard Williams, could leave for the Smalls. They found that the keepers, huddled together in the rickety remains of the lighthouse, had existed throughout their three weeks’ ordeal on bread and cheese alone.

An unusual view of the Smalls lighthouse. By lying on the helideck and pointing his camera downwards during a storm a former keeper has caught the moment when a wave sweeps over the reef and swirls around the base of the tower. The landing stage where the a relief launch could tie up in calmer conditions is on the left.

(Barry Hawkins)

During that winter the Smalls were once again returned to darkness. A measure of its necessity was demonstrated at 2 am on 30th December, when the brigantine Fortitude bound from London to Liverpool struck, with the loss of 11 hands. The wreckage drifted ashore over the next week. On 18th June 1813 a local newspaper reported the “Lighthouse repaired and light there” heralding the light that once more shone out from the Smalls.

Twenty-one years later, on 20th February 1833, another of these storms was equally destructive in its effect, only this time resulting in a loss of life. A freak wave broke over the rock, but instead of rolling through the legs, climbed up them to smash its way through the floor of the keepers’ quarters, flattening two walls. The iron range in one corner was allegedly compressed flat by the weight of water before being carried out and dropped into the boiling surf. For eight days the petrified keepers had to cook by the lamps in the lantern. One of the keepers later died from the injuries sustained on that day.

After its automation in 1987 the light in the lighthouse operates continuously – even in bright sunshine!

(Author)

By 31st July all was duly patched up, further wooden struts added around the legs, and a new light room returned to service. Despite the many refits it had undergone and the numerous extra legs it had sprouted, Whiteside’s structure still managed to retain its unique appearance. It did not, however, appear to be distinctive enough to prevent the Manuel of Bilboa, en route from Liverpool to Havana, striking the rock on which it was planted in broad daylight on 9th July 1858. The 12-man crew had just time to leap on to the reef before their badly holed boat drifted off for 3 miles before finally being swallowed by the sea. The keepers fed and kept the crew using the six months’ supply of food in the stores for sustenance of its inflated complement, although conditions must have been somewhat cramped.

Although it was certainly isolated, the Smalls rock is in the middle of one of the busiest shipping lanes around our coasts. The majority of trade in and out of Liverpool passed the rock and its lighthouse, as did that bound for Scotland or Ireland. With the 19th century’s flourishing sea trade came healthy profits from the light dues, over £6,700 being recorded for one year. Trinity House was well aware of this profitable beacon which was still in private ownership, and in 1823 offered to purchase it. The joint lessees were now the Rev A. B. Buchanan, (Phillips’ grandson), and Thomas Clarke, who valued their property at £148,430. The Elder Brethren considered this too high and proceeded no further with the matter. The profits in the meantime continued to mount. By the Act of Parliament of 1836, ownership finally changed hands on 25th March with 54 years of the lease remaining. Trinity House had to pay £170,468 for its purchase, an amount fixed by a local jury as appropriate compensation, yet still £22,000 in excess of their original offer! It is interesting to compare the similarity of these events with those of the Skerries in the previous chapter.

As the 19th century progressed a new breed of lighthouse engineers were erecting their towers on isolated reefs around our shore. The majority of these were of stone construction, giving solid, sturdy towers which resisted the ocean’s tumult. Out on the Smalls, Whiteside’s wooden light bravely continued in its vigil, although requiring almost constant repair. It was now extremely shaky on its legs, and during heavy seas the whole structure rocked and trembled with each crashing blow, the force of which had been known to fling a clock hung on a wall on to a bunk on the opposite side of the room. It was in 1801 that the great Robert Stevenson had described it, rather unkindly, as, “...a raft of timber rudely put together, the light of which is seen like the glimmering of a single taper.” Fifty years later it was still standing, although aged and frail. Few people would care to say how much longer Whiteside’s brave wooden beacon would last. It was near to its end, and if Trinity House did not take it down then it would not be long before the Atlantic would reclaim the Smalls.

There were tentative plans for another Smalls lighthouse in 1849 showing that a site had been chosen on the reef for a new stone tower, but it wasn’t until 1859 that work commenced. Whiteside’s structure had lasted for over 80 years, and while it had needed reinforcement, his principle was basically sound. Today this design is used the world over as a basis for lighthouses in certain situations. This fact ensures that we cannot forget Henry Whiteside and his lighthouse on stilts that he placed on a tiny Welsh rock in the midst of wild seas.

The construction of Trinity House’s new tower was entrusted to the capable hands of James Douglass, their chief engineer. He chose the same rock that Whiteside had done, only a short distance away from the existing light. Its profile was based on the now familiar outlines of Smeaton’s Eddystone tower – a smooth tapering curve rising gracefully from its base. The designer and consultant engineer was the equally famous James Walker, who paid as much attention to details such as sanitation as he did to the actual construction. In fact, the Smalls was one of the first rock lights to have a water closet incorporated in the design. It was Walker, too, who is credited with the novel idea of building the base of the tower in a series of steps to entrance level, the purpose of these being to break the force of waves crashing against the base and preventing them rolling up the sides. This design was later to be improved upon at such sites as Eddystone and the Bishop Rock by standing the tower on a solid core of masonry. Its function was exactly the same.

While the new tower was under construction, the Smalls was descended upon by a party of Royal Commissioners to inspect progress. The method of construction followed the now standard pattern of cutting and shaping the stone blocks on shore to obtain an exact fit and then transporting them by boat to the site. During their visit the Commissioners noted that:

Each stone has a square hollow on each edge, and a square hole in the centre; when set in its place, a wedge of slate, called a “joggle”, fits into the square opening formed by joining the two upper stones. The joint is placed exactly over the centre of the under stone, into which the joggle is wedged before the two upper stones are placed. The result is, that each set of three stones is fastened together by a fourth, which acts as a pin to keep the tiers from sliding on each other. The base of the building is solid. Two iron cranes slide up an iron pillar in the middle, and are fixed by pins at the required position as the work advances. The two are used together, so as to obviate any inequality of strain.

By 7th August 1861, just two years since it was started, the tower was complete. Such a speedy rate of progress was due, no doubt, to the rapidly advancing technology in lighthouse engineering, and also to the fact that the Smalls rock was not continuously being covered by tides or swept by waves, thus hindering the early and most vital stages.

The Smalls now had a splendid new tower, 141 ft high, and a worthy and fitting successor to Whiteside’s wooden refuge. At some time subsequent to its inauguration it was painted white with three broad red candy stripes as an aid to identification. Although life in the new tower was considerably more comfortable than in its predecessor, the loneliness and isolation inside its granite walls still continued to test the endurance of the men who inhabited it. One assistant keeper, who lived normally in Ealing where he was a watchmaker, was under no illusion that he “...would rather be anywhere on shore at half the money,” because “This is rusting a fellow’s life away.” Curiously enough, his head keeper, a Welsh farmer, preferred the Smalls to any other post, either a rock station or on shore.

Despite its isolation, modernisation of the Smalls kept pace with the technology of the time. The first example of this occurred 24 years after its completion when the fixed white light that was visible for 15 miles had its character changed to occulting (a steady light with a total eclipse at regular intervals with the period of darkness always less than the period of light) with a fixed red sector light. Two years later the original fog bell was replaced by an explosive signal, originally every 5 minutes but later every 7½ minutes. In 1902 the Smalls was connected to an electric telegraph, but this was, “for life saving purposes only.”

Further progress took place in 1907 when a 1st order catadioptric mercury-float optic was installed with the light coming from a 75mm paraffin vapour burner that gave a group flash of 3 every 15 seconds that could be seen from 17 miles away. The optic was rotated by a hand-wound weight-driven clock. At the same time a new red sector light, visible for 13 miles, was introduced in a room below the main lantern, 107ft above the water line, to mark the Hats and Barrels rocks – two satellites of the Smalls reef.

By 1928 the telegraph had been replaced by a telephone connection via a 1¼ins underwater cable which enabled the keepers to report shipping movements to Lloyds. It is also about this time that there are reports of a wind-driven generator being fitted to the lantern roof. There is nothing new, it seems, in wind power. For the next forty or so years things remained essentially the same on the Smalls apart from the arrival of an electric winch, electric domestic lighting and VHF radio telephone.

1970 saw a major modernisation program. The Smalls was the first Trinity House station to be fitted with a 400W metalarc electric lamp, its 1 million candlepower made it visible for 26 miles. This replaced the paraffin vapour burner inside the existing optic. Electricity also took over the rotation of the lantern and powered a newly installed ‘racon’ (radar-beacon). Down on the reef itself, fuel oil and water storage tanks were constructed about 66 feet from the base of the tower. The fog signal was upgraded to three supertyfon compressed air generators.

In 1978 a helideck of a design almost identical to that on the Eddystone was erected above the lantern to enable helicopter reliefs to be accomplished without the keepers ever leaving the tower. Prior to this date, helicopter reliefs had been established by landing the helicopter on the reef itself adjacent to the tower. These reliefs obviously couldn’t take place when the sea was sweeping over the reef or there was a remote possibility of it doing so. Even though this system was theoretically more reliable than a boat relief, it was by no means certain. A helideck above the lantern would make helicopter reliefs virtually guaranteed. Any keeper stationed on this desolate outpost could be almost sure that he would return to his family on time, which must have done much to alleviate the tedium of such a posting. Only fog or a tearing gale might cause a postponement.

The final modernisation on the Smalls reef coincided with Trinity House’s ongoing program of automation. The last keepers of the Smalls were withdrawn on 15th May 1986 after a LANBY (Large Automatic Navigation BuoY) was towed into position – delayed by several days because of bad weather, 1½ miles south west of the tower. The automation process involved large amounts of ‘coring’ – drilling out 35 metres of circular ‘tubes’ through the granite walls and floors to accomodate all the new wiring, ducting and piping required to connect up the new equipment. Part of the process also required the installation of a powerful 10kW diesel generator, together with a standby, designed to run for 6 months without attention. Automatic fog detectors set off three powerful new fog signal emitters arranged around the lantern gallery that can be heard from 3 miles away. An emergency beacon in case of a main light failure was installed on the lantern roof below the helideck.

The Smalls lighthouse is still the first sea-mark seen by vessels making for the oil terminals of Milford or the Bristol Channel ports from the west. The broad red and white bands that used to distinguish it from the cold, grey wastes of ocean that surround it were sand blasted off during June 1997, returning it to the natural granite and to an appearance almost identical to when Douglass built it. Its helideck supports were painted red at the same time giving it a vaguely similar appearance to the Eddystone. Since automation and the addition of a ring of solar panels around the helideck the main light flashes continuously – a permanent reminder that although there are no keepers looking out from the Smalls lighthouse, its function to warn of the reef on which it stands is still the primary purpose of the Trinity House service.

A fairly rough day at the Smalls with lots of white water. The lighthouse is now automatic but on the helideck are what look like three rubber bags that would contain fuel for the generators or drinking water.

(Air Images Ltd)