A stormy day at the Longships lighthouse with white water everywhere. No chance of a boat relief today!

(Author)

A stormy day at the Longships lighthouse with white water everywhere. No chance of a boat relief today!

(Author)

FEW VISITORS to Cornwall can fail to have been drawn to the very extremity of this country, to the rugged promontory known as Land’s End. Here, sea and land meet in conflict; a battleground of crashing waves, foaming surf and precipitous cliffs. Although mistakenly believed to be the westernmost point of the British mainland (it is not, for this distinction goes to Ardnamurchan Point in Argyllshire which extends some 40 miles further west than Land’s End), it nevertheless draws countless thousands of tourists each summer to gaze at the last of the English landscape as it drops vertically beneath the Atlantic surf. The ritual of this pilgrimage involves standing on cliff tops to gaze westwards across the grey fields of ocean to the site of the legendary land of Lyonesse, home of Camelot and the Arthurian knights, before it was supposedly engulfed by the sea.

However, their westward gaze will, in all probability, be drawn from the distant horizon to focus on a line of rocks barely a mile from where they stand, on top of which rises the shapely symmetry of the Longships lighthouse. It is a scene remembered, and much photographed by every visitor to this outpost of mainland Britain, more vividly perhaps if viewed at sunset, when the rocks and lighthouse are thrown into silhouette against a flaming sky, to become a lonely convoy of ships that give the reef its name.

The tidal races, swirling mists and half submerged rocks made the Longships a nightmare for vessels rounding the toe of England. A passage between the reef and mainland was fraught with difficulties caused by vicious currents, a confined channel and razor-sharp granite, yet a course too far westwards was liable to draw ships on to the infamous Seven Stones reef. Vessel after vessel was swept to destruction around these few short miles of coast, each met with a gleeful reception from the wreckers who allegedly thrived on the rich pickings this coastline offered. Nowhere in Britain, it was said, was there a more evil stretch of coast – something the local wrecking fraternity took full advantage of. Children of the coastal villages were taught to pray “God bless father ‘n mither an’ zend a good ship to shore vore morning,” while their parents made considerable efforts to see that their children’s prayers were answered by setting up false beacons to lure heavily laden vessels on to a coastline which offered no second chances. It was a lucrative business and one which it was difficult to stop.

When seen against a setting sun from Land’s End, the rocks on which the Longships lighthouse was built were thought to resemble a line of ships, hence ‘Long -ships’.

(Author)

As long as this coastline remained unlit, ships would continue to end their days at the hands of the sea, with the likely help of those who gleaned a living from it. For century after century, each night the coast around the Longships and Land’s End was plunged into inky blackness where few vessels could survive in heavy seas. John Ruskin once described this area as “...an entire disorder of surges...the whole surface of the sea becomes a dizzy whirl of rushing, writhing, tortured and undirected rage, bounding and crashing in an anarchy of enormous power.” The regularity that ships struck this coast forced Trinity House to take notice, although it was not until the end of the 18th century that they were stirred from their lethargy.

It was not solely the Longships which were causing Trinity House concern. In the vicinity of Land’s End were two other reefs whose toll of vessels was equally appalling, if not more so, than the Longships. Eight miles distant to the south-west was Wolf Rock, a notorious shoal of granite, on to which many ships had piled with catastrophic devastation, and 4 miles to the south-east of Land’s End was the Runnelstone, the stumbling block for a good number of vessels attempting the ‘short cut’ between the English and Bristol Channels through the landward passage past the Longships. If any one of these obstacles were found singly, the navigation around it would have called for the utmost precision, yet having all three together in the same small area of map was a situation which tested the nerves of the most competent mariner. Few ships ventured near these evil rocks during darkness or poor visibility. Tempting fate was one thing, but actually offering the lives of a ship and crew was a risk few captains would take.

In June 1790 Trinity House instructed John Smeaton, after his triumph on the Eddystone, to survey the island of Roseveern in Scilly with a view to placing a beacon there. While this would doubtless aid navigation around the intricate channels of these islands, being nearly 30 miles distant from Land’s End it would be of little consequence to the harassed mariners picking their way around the English coast, and so came to nothing. By June of the following year Trinity House had obtained a patent from the Crown for something a little more practical. It was for the erection of a lighthouse on the Wolf Rock, although the Brethren were unwilling to undertake the construction themselves and so leased the rights to a Lieutenant Henry Smith. Smith, too, it appears, was daunted by this task, so the terms of the lease were altered to provide a lighthouse on the more accessible and higher Longships rock, with beacons on the Wolf Rock and Runnelstone. In return for keeping the light dues Smith was charged a rental of £100 for 50 years.

A section through the original Longships lighthouse built by Samuel Wyatt shows the arrangement of the three rooms it contained. This Trinity House plan shows the tower was built on the ‘Great Carnvroaz Rock’ next to a ‘Rock called The Old Man’

(Trinity House)

A design was prepared by Samual Wyatt, who from 1776 had been architect and consultant engineer to Trinity House. The first stone was laid in September 1791. Cornish granite was used for the blocks, each one undergoing the trenailing and dovetailing which had become accepted practice since Eddystone. They were carefully fitted together in the base at Sennen, then shipped across the 1½ miles of water, before finally being put to rest with waterproof cements on Carn Bras, the highest rock of the Longships reef reaching 40 ft above the waves.

Wyatt’s tower was of a short, stumpy design of only three storeys elevation, rising to a mere 38 ft. The walls were 4 ft thick at its base tapering to 3 ft below the lantern and enclosed three rooms, the lowest housed the fresh water tanks, above which was a living room followed by a bedroom. The original lantern was of wood and copper construction and contained 18 parabolic reflectors in two tiers, each with its own Argand lamp. These showed a continuous fixed beam visible for 14 miles. By way of economy, metal sheets were installed against the landward panes of the lantern so no light could be observed from that direction, with a resultant drop in oil consumption. When viewed from the sea Wyatt’s tower was not only unusual because of its squat outline, it also possessed stout metal stays which were affixed between the lantern gallery and lantern dome on the outside, suggesting that these might have been added as an afterthought. The first light to end the centuries of darkness around the Longships was seen on 29th September 1795.

With such a powerful indication of the imminent dangers, fatalities amongst the rocks and cliffs fell dramatically. Robert Stevenson, on a visit to the lighthouse in 1801, was much impressed by the light it exhibited, although he was not so enamoured by the conditions in which the keepers lived, especially when he discovered they cooked all their food in the lantern. A subsequent visit 17 years later found this state of affairs had deteriorated further and the whole was “in very indifferent order.” The keepers were of a “very ragged and wild-like appearance,” and appeared to have been neglecting their duties. Stevenson further noted the poor condition of the reflectors which caused the beam to be “quite red coloured.”

In the meantime, Henry Smith was having considerable financial troubles. He was adjudged “incapable of managing the concern” and by 1806 the luckless Smith found himself a resident in the Fleet Prison, London – a well known debtors jail. Being the innovator of the Longships light, Smith was shown exceptional goodwill and generosity by Trinity House who took over the running and maintenance of the light while remitting all profits to his family. It must be mentioned here that the similarity of these events when compared with those that took place at the Skerries lighthouse is remarkable.

A very rare photograph by Nicholas Blake Lobb of Samuel Wyatt’s original Longships lighthouse taken in about 1870 before work started on Douglass’ second tower. All three keepers are visible; one on the gallery and two on the platform outside the tower.

(courtesy of Mike Millichamp)

Although only a little over a mile from the shore, the existence of the keepers on the Longships could be particularly isolated. For this reason four keepers were assigned to the station, two being on duty at any one time, while the other pair were on shore leave. Spells of duty lasted a month at a time with a month’s leave to follow. Wages were £30 per annum with food provided at the lighthouse, although when off duty it was the keeper’s responsibility to take care of his own welfare. Many took on second jobs during their time on shore. However, in 1861 an incident is recorded which supposedly caused an alteration to these arrangements. One of the two keepers died, which left his companion to tend the light continuously until he could be relieved. Since then, the story goes, three keepers were stationed in the light at any one time to prevent a similar situation arising. The authenticity of these events is dubious, particularly as they are almost a replica of the occurrences that took place on the Smalls in about 1800.

Such isolation inevitably prompts the imagination of fiction writers with whom the lighthouse is a favourite setting. When this is the case the dividing line between truth and fiction becomes blurred and it can be difficult to separate the fantasy from the fact on which it was probably based. Nowhere can this be better illustrated than on the Longships, where the lighthouse has featured in many different stories of questionable origin, yet all appear to be the result of some particular incident and have a grain of truth.

There exists in a Cornish newspaper of 1873, for instance, the story of a little girl who single-handedly continued to light the lantern every night after her father had been kidnapped by wreckers while fetching supplies on shore. Thinking this would prevent any light being shown from the Longships the wreckers sat and waited for the vessels to blunder their way on to the unlit coast, yet had failed to appreciate the courage of the keeper’s daughter who, unable to reach the lantern wicks, had to stand on tip-toes on the family bible to accomplish her task. This story captured the imagination of a contemporary novelist, James Cobb, who in 1878 produced The Watchers on the Longships in which this incident appears.

There is also a piece of fiction by the same author concerning a keeper whose hair had allegedly turned grey overnight as he had not been informed of the noises generated by air being compressed in fissures of the reef which produced a loud wailing noise when released. This led the author into the erroneous idea that, “more than one untrained keeper has been driven insane from sheer terror.” Strangely enough, a newspaper report in December 1842 relates incidents of two years previously when two keepers in the Longships were marooned for an incredible 15 weeks, at the end of which time one of the men, by the name of Clements, arrived on shore with his hair, eyebrows and eyelashes completely grey. He had started his turn of duty with black hair.

The Trinity House plan of 25th August 1868 showing the site for the proposed new lighthouse and the elaborate arrangement of steps, walkways and bridges that would connect the entrance door to one of three landing stages.

(Trinity House)

During favourable conditions Wyatt’s tower proved extremely suitable for the function it was designed to fulfil. Its unceasing beam gave admirable warning of the reef on which it stood, yet during heavy seas its efficiency was seen to drop markedly. Being a little under 80 ft from the high water mark, it was quite within the reach of rogue waves which easily passed over the top of the tower during the many winter storms. Such breakers caused the nature of the light, as seen from ships, to alter from a fixed beam to an occulting flash, ie, a beam whose period of darkness is less than the period of light. The consequences of navigating by such false information could, of course, be disastrous.

Not only this, some of the storms experienced by Wyatt’s tower were of such force that the waves had been known to smash the lantern panes and extinguish the lamps. On 7th October 1857 seven burners were doused by water entering the lantern room through the roof cowl, and only a few years later a contemporary writer noted that many of the lantern room windows had been “dashed to pieces by the spray of the ocean during the winter’s tempest.” This, it seemed, was not an infrequent occurrence, for only 20 years after its construction a report in the Royal Cornwall Gazette of 7th January 1815 stated that the Longships lighthouse had been completely destroyed by one of the numerous storms that battered the Cornish coast at that time. It was retracted a week later and a full story carried in the West Briton of 13th January. “The violence of the waves broke in part of the roof, which is of thick glass, and for several days the people in the house were unable to ascend to repair the damage. This, however, has now been done and the light is exhibited as usual.”

Competent though Wyatt undoubtedly was to hold his position as Trinity House architect, it was obvious that he had seriously underestimated the capabilities of an ocean in fury around the Longships. The water over-topped the lantern with such regularity that during times of heavy seas and high winds the lighthouse, far from aiding navigation through these troubled waters, was a positive liability to it. The solution was clear – a taller structure was required, out of reach of the waves, yet this did not finally materialise until the end of 1873.

Prior to this event came the change of ownership of the old Longships tower from the family of Henry Smith to Trinity House. This was done under the same Act of 1836 which was responsible for the Smalls and Skerries being brought into public ownership. It was also deemed necessary for the same reason – excessive amounts of profit being taken from light dues caused by a boom in sea trade during the early 19th century. Records show that after deducting maintenance monies of £1,183 in 1831 the profit was £3,017. In just five years this had risen to £8,293. Trinity House was now regretting its earlier kindness to Smith and his family who benefited to the tune of £40,676 when the leases were bought back from them in 1836 with only 9½ years left to run.

By 1869 work was all but complete on the Wolf Rock lighthouse. William Douglass, resident engineer at that site, was instructed to prepare plans for a new tower to succeed Wyatt’s on the Longships. Supervision of its erection was left in the capable hands of Michael Beazely who had assisted Douglass at the Wolf and followed him from it. In fact, much of the machinery, tools and boats used there were again put to work on the second Longships tower. Granite was the obvious choice of stone, either from Cornish quarries or from northern France.

Block laying commenced in 1870 and being in such an advantageous position, 40 ft above all but the highest seas, work proceeded swiftly. Soon a second tower could be seen rising on Carn Bras. When the tower rose to a suitable height, a passageway was constructed between the two towers which were adjacent to one another. Also, part of the actual reef itself that was in the line of sight from where the entrance door new tower was planned was blasted away. A temporary light fixed to the top of a balance crane that rose from the centre of the new tower took over the warning functions as the new tower grew ever taller.

There were, however, moments of alarm such as took place during the winter of 1872 when 15 men were marooned in the two lighthouses by heavy seas for many weeks. Provisions ran low, despite some being hauled through crashing waves from a supply boat. It was shortly after Christmas that these poor souls could be snatched back into civilisation by a Penzance steamer.

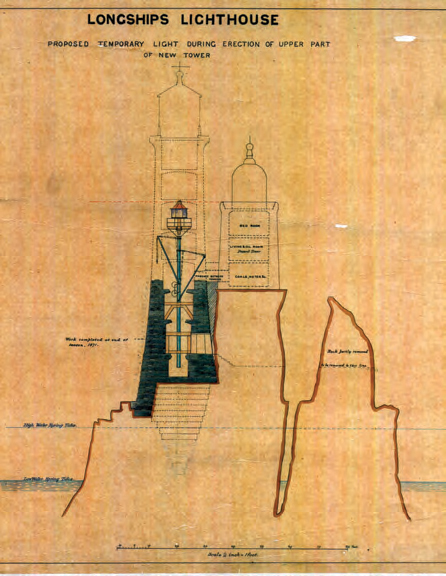

Another incredibly detailed Trinity House plan dated 30th January 1872 showing how a temporary light was to be placed on top of the growing Douglass tower which was built alongside Wyatt’s original light. This plan also shows how much of the actual reef was to be removed from around the new tower to give clear visibility in all directions.

(Trinity House)

In August 1872 the final stone was laid amid much celebration. The period between then and the end of the following year was occupied with fitting out and the installation of the lantern. Completion was in December 1873 when a fixed white light could once again be seen radiating from the Longships, this time from the top of a 69 ft tower, raising the lantern to almost 114 ft above high water. It had cost £43,870.

The original and beautifully hand-painted Trinity House plan of August 1868 for William Douglass’ second Longships lighthouse. It has obviously been well used and needed repair work with adhesive tape, but is still a fascinating and detailed document.

(Trinity House)

The design was very similar to what members of the Douglass family had already produced; a circular granite tower with gracefully sloping sides, the wall thickness diminishing as the height increased, the first few courses of blocks stepped to break the force of the waves, and large fresh water tanks holding 1,800 gallons let into the solid base. A huge gun metal door was positioned at the top of a rather elaborate set of semi-circular steps – the sort that would not be out of place at the front door of an imposing mansion. Behind the door are four rooms; an oil store, living room/kitchen, bedroom and service room before the lantern itself is reached.

A 1950s postcard view of Longships lighthouse on what looks like a relief day. The Trinity House flag is flying and two keepers are looking out for an approaching boat from the lantern gallery. It would be another 20 years before Longships got a helideck and boat reliefs became a thing of the past.

Radiating from the base of the tower are a series of walkways, steps and even iron bridges hewn into different aspects of the reef. They lead to three separate landings called the North Point, the Pollon (Pollard) or South Landing and the Bridges. Having a choice of three enabled stores and keepers to be landed at varying states of wind and tide, although this was no simple task during even the best of conditions. The sea is in constant tumult in and around these granite humps, frothing and boiling angrily as the complex currents and swells collide. A calm day around the Longships is a rare day indeed.

The keepers and their families lived in a row of cottages above Sennen Cove that was visible from the tower. With the use of a telescope it was possible to see the lighthouse clearly from the cottages and so the keepers were able to devise a system of communicating between the two. By painting a white border around the front door it was possible for a keeper to stand on the steps and use semaphore flags to communicate with the shore. Later still came electronic communication. A former principal keeper there once wrote:

“We are rather more fortunate at the Longships than most other rocks, with regard to signalling we being well up in the Morse Code and Semaphore, great strides have been made, we are now able to hold communication with the Wolf Rock, a distance of nearly 8 miles, we also signal to dwellings ashore every night and day and are now able to get all the latest news for the Service and private use which is a very great boon, the old style of signalling by hoisting flags being almost obsolete...”

An RAF rescue helicopter hovers over Longships lighthouse while something is winched down to the keepers on the gallery.

(Ministry of Defence)

Wyatt’s tower was dismantled soon after the new light was brought into service. It is Douglass’ tower which now attracts the wistful gaze of Land’s End tourists. During the summer of 1967 modernisation found its way on to the Longships. The old paraffin burners were removed and replaced by a new optical apparatus revolving around an electric bulb. Generators to power this were installed beneath the optics. Replaced at the same time was the gun cotton fog signal by a more modern fog horn. The character of the light has also changed, and now a red and white isophase beam (equal periods of light and dark), every 10 seconds is visible for up to 19 miles in clear weather.

Longships was never a popular posting for Trinity House keepers. It has been described as, “...the most treacherous and dangerous rock in the Service, more lives having been lost there than the whole of our rocks put together...” and, “...it is indeed a very rough station.” The comparatively short tower meant conditions were cramped and uncomfortable, and in heavy seas, when all the storm shutters were closed, it was dark and damp inside. Worst of all was the distinct possibility of overdue reliefs.

Unlike most other rock stations the Longships is in the unusual position of being clearly visible in all but the most foul of conditions, yet at the same time highly inaccessible. Before helicopters took on this role, a boat relief of the Longships could be a very uncertain and unpredictable operation. An open boat from Sennen Cove had to edge its way into a narrow gully of Carn Bras to reach one of the three landings – something that was only possible in conditions that were virtually flat calm, and even then the sea between the rocks of the Longships was usually anything but. If the boat couldn’t tie up at the landing it was sometimes possible to transfer keepers and stores on the end of a jib – but often at the expense of a soaking.

Communication between the Longships lighthouse and the keepers cottages at Sennen used to be done by semaphore – as demonstrated here by two of the off duty keepers and their very disinterested dog.

(Mike Millichamp)

Ever since Carn Bras has had a lighthouse on it these landings have suffered much torment from heavy seas and swells which frequently wash over and smash rocks against them, even in comparatively calm conditions. Centuries of storms have broken and shattered the rock, requiring much repair work for the landings to remain serviceable. The last major damage occurred in December 1990 when violent storms smashed a huge chunk off the Pollard landing requiring considerable remedial work with rock bolts to prevent further deterioration. Delayed boat reliefs were part and parcel of life on the Longships.

Things improved no end when a helideck was erected above the lantern in the late 1970s. The helicopter journey from the Trinity House cottages at Sennen took just two minutes and was independent of sea conditions, unless these were so bad there was a possibility of waves reaching the helideck itself – not uncommon during winter storms. The helicopter relief certainly improved travel to and from the Longships, but it couldn’t improve conditions within the tower for the keeper’s month of duty.

It was a prime candidate for automation and the inevitable started in 1987 and was completed early in 1988. It followed the now standard procedure of installing new diesel generators, electric fog signals and a fog detector. The fresh water tanks in the base of the tower now store enough fuel oil for the generators to operate for 6 months without attention. All this was done without interrupting the normal operation and warnings the lighthouse gives. It is now monitored and controlled, like all the rest of their lighthouses, from the Trinity House Control Centre in Harwich.

Westerley gales can drive the waves to spectacular heights up, and sometimes over, the Longships lighthouse. Each wave causes the tower to shudder and the whole of the Longships reef becomes a confused scene of white water.

(Paul Campbell)

The Longships’ tower casts a long shadow on an autumn afternoon, while on the helideck we can just see a silhouette of a keeper lowering supplies through the trapdoor.

(Author)