The present Longstone lighthouse was built between 1825–6 by Joseph Nelson on the outermost of the Farne Islands.

(Author)

The present Longstone lighthouse was built between 1825–6 by Joseph Nelson on the outermost of the Farne Islands.

(Author)

NO WORK about isolated lighthouses or lighthouse stories would be complete without containing what is probably the most well known story about a British lighthouse ever recounted. It is set off the rocky Northumberland coast at a lighthouse known as Longstone, and while this name might not be immediately recognisable, the name of the lightkeeper in 1838 will be instantly familiar to generations of school children to whom this drama has been told. His name was Darling, and it was the courage of his daughter Grace which has ensured the place of the Longstone lighthouse in our maritime history.

The Longstone lighthouse was built on the outermost of a series of about 25 islands known collectively as the Farne Islands, situated some 7 miles off the Northumberland coast – a favourite perch and breeding site of countless thousands of guillemots, puffins, razorbills, terns and gulls. The story of the Farne lighthouses is a long and involved series of events which began well over a century before Grace Darling was to focus attention upon them. In essence, the lighting of these dangerous islands and reefs was accomplished in a rather haphazard manner, with the construction, modification, abandonment or demolition of several towers, of varying effectiveness, placed on several of the islands within the group. The present Longstone tower is a comparatively recent addition to the Farnes.

The isolated nature of the islands made them a favourite refuge of hermits, recluses and saints. It is said, for instance, that St Cuthbert lived alone on Farne in the 7th century. Although only a handful of miles from the mainland, their isolation was due in most part to the fact that their rocky nature and low profile – many rising only a few feet out of the surf – made them difficult to approach and an even greater danger to shipping wishing to avoid the half-submerged reefs and craggy ledges. During the 18th and 19th centuries the inhabitants of the Farnes were known to supplement their income from the salvaging, or looting, of wrecked vessels, much as their Cornish counterparts were prone to do. A premium was paid, which doubled after midnight, to the first person reporting a shipwreck, while the Sailing Directions for the early 19th century gave little comfort by noting that, “Dead bodies cast on shore are decently buried gratis.”

The original Trinity House plans for Joseph Nelson’s Longstone lighthouse of 1826.

(Trinity House)

A painting by Thomas Musgrove Joy showing Grace Darling and her father in an open boat trying to rescue the survivors from the wreck of the Forfarshire on the Big Harker rock. In the background is the Longstone lighthouse.

(RNLI)

The scene in the kitchen at the Longstone lighthouse after the rescue of the survivors from the Forfarshire. Grace and her father are on the right, comforting the survivor wrapped in a blanket, while her mother offers hot soup to another.

(RNLI)

The history of the Farne Islands lighthouses starts in 1669 when Sir John Clayton, a long-time antagonist of Trinity House, applied for a patent to erect four lighthouses along the east coast of England at the Farnes, Flamborough Head, Foulness near Cromer, and Corton near Lowestoft. He was granted the patent for all the proposed sites and proceeded to erect stone towers at all four locations at a cost of £3,000. However, although the Crown had specified dues of 2½d per ton for laden vessels and 1d per ton for unladen ones, payment by merchants would be voluntary. He lit the tower at Corton on 22nd September 1675 but because of difficulties in collecting dues, not helped by Trinity House establishing a rival light for which they charged no dues, he was unable to light the other three towers and eventually had to extinguish the light at Corton in 1678.

Clayton’s good intentions had left the Farne Islands with a stone tower with no fire on it, yet the islands still claimed shipping with alarming regularity. Representations were made by local shipowners to Trinity House who successfully applied for a patent, and in due course leased this on 6th July 1776 to Captain John Blackett and his family, who lived on the islands. He in turn built two lighthouses, one on the Inner Farne Island and the other on the smaller Staples or Pinnacle Island. On the Inner Farne he erected a 40 ft stone tower, known as Cuthbert’s tower, on top of which was lit a coal fire, while on Staples Island a stone cottage was built with a sloping roof and a glazed lantern placed centrally on the ridge. The light source for this lantern was thought to be oil lamps. It is at this cottage that the first connection between the Darling family and the Farne Islands can be seen, for Robert Darling, the grandfather of Grace, was a lightkeeper here in 1795.

It was not long before complaints were heard regarding the positioning and effectiveness of the Staples Island light. To improve matters a further roughly-built tower was erected in 1791 on the adjacent Brownsman Island which supported a coal-burning grate. This was approximately 21 ft square in section and about 30 ft high with an external ladder. Even this measure did little to improve the visibility of the lights which could frequently be obscured by smoke. Trinity House was naturally keen to replace the inefficient coal grates with Argand lamps, and so with a new patent of November 1810 proceeded to build two further lighthouses, under the supervision of Daniel Alexander the Trinity House architect, one on the Inner Farne adjacent to the existing tower, and the other on the Longstone rock – an outlier of the group. Both lanterns were fitted with Argand lamps and reflectors and had revolving optics. They cost together £8,500.

The actual boat in which Grace Darling and her father carried out the rescue of September 1838. It has been named after her and now rests in the Grace Darling Museum, Bamburgh.

(RNLI)

Trinity House granted a further lease to the Blackett family which gave them the profits from the two lights after maintenance and running costs had been deducted by the Corporation who had now taken over the running of the two stations. This was yet another example of generosity by Trinity House which they were later to regret and practically a carbon copy of the events at the Skerries lighthouse dealt with earlier. When the Elder Brethren were keen to buy back the lease of this lucrative source of funds in December 1824 with 15 years of the lease still to run, it cost them a staggering £36,445 for the two lighthouses. Yet this was not the final cost. It had been decided that a new stone tower was required on the Longstone reef, to be built by Joseph Nelson, which in turn was to cost a further £6,063.

The new Longstone tower was 85 ft from base to vane and painted red with a white band to make it an easily distinguishable daymark. It had a lightkeepers’ house attached and was enclosed by a boundary wall. When its revolving white flash every 30 seconds was first seen on 15th February 1826 it was the signal for the demise and subsequent demolition of the tower on Brownsman Island. The keeper was transferred to the Longstone light – his name was William Darling and he took with him his wife and 11-year-old daughter Grace, shortly to become more famous than William could ever have dreamt possible.

Grace Horsley Darling was born in the year of the Battle of Waterloo on 24th November 1815 at Bamburgh, Northumberland. Her early years were spent with her parents, brothers and sisters in the lighthouse on Brownsman Island. Her education, apart from a basic grounding in elementary subjects, was what she learnt from her parents and she soon developed characteristics that were clearly inherited from her father – untold patience, conscientiousness and steadfastness. She was a quiet, unassuming, well principled girl who gave no hint of having the slightest heroic streak within her. After her brothers departed to continue their education on the mainland, Grace was left to continue her life helping her father with his duties in the new Longstone lighthouse.

Having such an intimate relationship with the sea, Grace would have witnessed all its moods; a placid millpond in which the Farnes’ seal colonies gleaned their food, then quickly transformed into a raging killer as an 8-knot tide ripped between the rocky ledges. Mountainous seas often crashed on to sea-polished islets such as the Big and Little Harkers, Nameless Rock, or Gun Rock. She would have seen that the rock on which the lighthouse stood, only 4 ft above the high water, was swept in every gale by curtains of spray and foam, a scene that would fix in her memory the fact that the Farnes offered no half chances to vessels unlucky enough to drag their hulls over the teeth which surrounded her home.

In 1838 Grace was 22 years old and her life had so far been devoid of the sort of drama which would shortly bring her to public prominence. On 5th September, the Forfarshire, a luxurious new pleasure steamer, left Hull on one of her regular trips to Dundee with 63 passengers. During the night of 6th–7th the wind veered to the north and rose in strength to gale force with an accompanying worsening of sea conditions. On Longstone, William Darling and Grace busied themselves with securing the lighthouse’s coble boat to its supports and generally preparing themselves for the gale which, as fate would have it, coincided with a high tide. They knew to expect a rough night but were not unduly perturbed.

An interesting view that shows how close the Farne Islands are to the Northumberland coast beyond. The extensive rock above the lighthouse tower is the Big Harker from which Grace Darling and her father rescued the survivors of the Forfarshire in 1838.

(Author)

On board the Forfarshire steaming steadily northwards along the east coast, a problem with the boilers had become apparent. A leak had sprung allowing steam and boiling water to escape into the engine room. Captain Humble ordered the pumps to be started in an effort to clear the water but these were unable to deal with the vast amounts of scalding water now escaping from the boiler. Eventually, the sheer volume of water extinguished the boiler fires and the ship was left without power in a rising gale. With storm force winds beating down from the north on the crippled vessel, the captain gave orders for the sails to be set in a desperate attempt to keep the ship on course. It was a futile gesture in such conditions, the ship went about and became unmanageable, and efforts to effect some control by dropping the anchors were unsuccessful.

One of the many portraits of Grace Darling painted after her heroic rescue.

(RNLI)

Captain Humble was in a desperate situation. He was in command of a vessel which had very little manoeuvrability and no engines, but it carried over 60 passengers and a valuable cargo. He had little option therefore but to try to find shelter amongst the Farne Islands, now appearing off the port bow, as it would clearly be folly to try to ride out the storm on the open sea. The light from the Longstone lighthouse shone bright and clear through the spray, but it was about this time that Captain Humble made the mistake that was to cost him the life of his ship and many of its passengers. He somehow mistook the position of this light, or was even confused as to which light he could see, and with his vessel drifting helplessly south on the tide the Forfarshire struck, between three and four in the morning an outlier of Longstone rock called the Big Harker, a rock rising sheer from 600 ft below the waves and so sharp and rugged that standing upright on it was said to be impossible, even when its surface was dry.

Almost immediately the vessel was ripped open and she began to break up. Most of the cabin passengers and crew were washed off the decks by mountainous seas, never to be seen again. A few lucky souls escaped in a boat. Captain Humble, with his wife in his arms, were last seen being swept out to sea. About 13 souls were fortunate enough to be able to scramble on to the rock or cling with numbed hands to pieces of broken vessel wedged in the crevices of the Big Harker. A constant deluge from curtains of icy water threatened to drag them from their exposed perch back into the foaming waters around them. Several hours of such an ordeal were too great for two adults and two children who were snatched back by the sea when exhaustion prised loose their grip.

Another Grace Darling portrait painted by Henry Parker on 10th November 1838 at the lighthouse.

(RNLI)

Inside the Longstones lighthouse Grace was having difficulty in sleeping. She was awoken just before dawn by the shrieking of the wind, but above this noise she thought she heard other cries – shouts of distress and anguish produced by human voices. She roused her father who produced a telescope and peered into the half light towards the direction of the noise. He was shocked by what he saw. Half a mile away he could just pick out the shattered remains of a once proud vessel, her masts snapped and sails shredded, being pounded against the Big Harker rock by heaving seas; but worse still was the small group of miserable souls huddled together on the adjacent rock in fear of their lives.

William Darling, Grace’s father

(RNLI)

Both Grace and her father knew that no boat would be able to put out from Bamburgh in such conditions and that if the survivors were not to perish a rescue would have to be attempted from the lighthouse. Mrs Darling was loath to let her husband and daughter undertake such a rescue, fearing that the wild seas breaking around the rocks would claim her husband and daughter also. No such thoughts entered Grace’s mind – she launched the flimsy coble that was kept at the lighthouse and with her father and her rowing in unison, set out across the raging ocean toward the shipwreck. The survivors were less than half a mile from the Longstone yet the sea forced the two rescuers to row for over a mile through the heaving swell and swirling currents before they were able to navigate close enough to the rock with the luckless survivors on. The flat-bottomed coble was not large enough to hold all the survivors so William Darling leapt on to the rock and assisted into the frail boat a woman survivor, who had earlier watched both her children swept to their deaths, one injured man, plus three of the crew. Grace in the meantime was fighting with the oars in a desperate attempt to hold her boat close to the jagged rocks, a feat of courage and strength of the highest order – the slightest misjudgement would have reduced the coble to splintered matchwood.

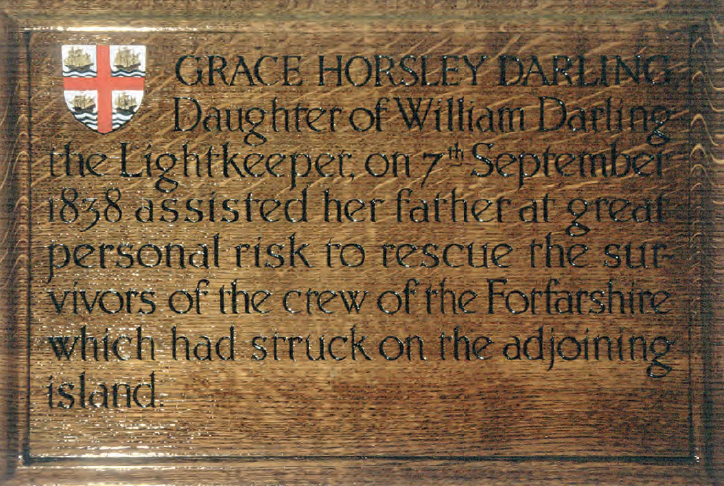

The rescue of the survivors of the Forfarshire wreck is commemorated by this wooden plaque on the wall of the room that was Grace Darling’s bedroom.

(Author)

Grace and her father returned to the lighthouse with the five survivors where her mother was waiting to help the injured man and woman into the shelter of the light. Grace remained with them to tend to their injuries while her father and two of the male survivors returned again to fetch off the remaining passengers without further loss of life. Half an hour after the rescue, much to the surprise of William Darling, a boat could be seen approaching the scene of the wreck. It contained the coxswain of the North Sunderland lifeboat, William Robson, his two brothers, and also Grace’s brother, William Brooks Darling. They had managed to put out from Seahouses but were too late to offer any effective help. The survivors spent three days in the lighthouse before they could be taken ashore to tell the story of Grace Darling and her heroic deeds.

Even so, it was many days before Grace’s part in the rescue became widely known. It was only when The Times asked “Is there in the whole field of history, or of fiction, even one instance of female heroism to compare for one moment with this?” a fortnight after the event, that more and more attention was focused on Grace Darling who was slowly but surely becoming Britain’s first national heroine. The public was clamouring to know more about this frail little girl and her act of bravery.

Probably a 1930s scene at Longstone lighthouse with a flotilla of open boats wedged into one of the creeks of the rock. The diaphone fog horn projecting from the roof of the building was bombed during World War II and never replaced – but the tower survived. It is difficult to tell from this view whether the lighthouse had acquired its white stripe yet.

Countless songs and verses of poetry were written of her deeds, even William Wordsworth was moved enough to produce his own tribute containing the lines:

And through the sea’s tremendous trough

The father and the girl rode off.

She was the recipient of bravery awards from many sources, including a gold medal from the British Humane Society, as well as sacks full of letters that were somehow delivered to Longstone. A national fund was raised with considerable sums of money being kept in trust for the somewhat bemused Grace. She and her father had to sit for seven artists within 12 days while others waited their turn. Locks of hair, supposedly Grace’s, and squares of material allegedly taken from the gown in which the rescue was undertaken were sold in vast quantities throughout the country. Steamers ran excursions to the Longstone lighthouse, and Grace even had offers to appear on the stage. Flattering testimonials were bestowed upon her, yet through all the national obsession with Grace Darling and the wreck of the Forfarshire, Grace herself remained comparatively unaffected by all the commotion, continuing to assist her father with his duties as she had done in the past.

Indeed it would appear that her father did not view the events of the rescue with such a sense of drama as did the rest of the country. It is clear from his entry in the lighthouse journal that such events were regarded as part and parcel of a lightkeeper’s life – the rescue was only one aspect of his function to save lives wherever humanly possible, and Grace’s involvement was coincidental in so much as she was only fulfilling the role of her brother who would normally have assisted his father had he not been on the mainland. The relevant entry in the log reads:

The steam-boat Forfarshire, 400 tons, sailed from Hull for Dundee on the 6th at midnight. When off Berwick, her boilers became so leaky as to render the engines useless. Captain Humble then bore away from Shields; blowing strong gale, north, with thick fog. About 4 am on the 7th the vessel struck the west point of Harker’s rock, and in 15 minutes broke through by the paddle axe, and drowned 43 persons; nine having previously left in their own boat, and were picked up by a Montrose vessel, and carried to Shields, and nine others held on by the wreck and were rescued by the Darlings. The cargo consisted of superfine cloths, hard-ware, soap, boiler-plate and spinning gear.

Nowhere, it will be noted, does Grace’s name appear, in this or any other entry relevant to the rescue. This was not out of spite towards his daughter; on the contrary, Grace was often regarded as his favourite child, but purely because it was considered perfectly normal for his daughter to assist him with his duties in the absence of his son, whether these duties be the mundane trimming of the lamp wicks or something a little more dramatic. Very little is mentioned in the lighthouse journal of Grace’s national fame apart from short entries regarding artists that visited the lighthouse followed by meticulous detail of the fish he caught or unseasonal breeding patterns of the sea birds. Clearly, William Darling thought very little of all the attention the rest of the country were paying his family.

In 1841, just three years after the Forfarshire rescue, Grace, who had a strong frame but was never particularly robust, became ill to such an extent that it was clear her health was deteriorating. What was at first diagnosed as a common cold did not respond to treatment and a subsequent investigation confirmed that Grace was suffering from tuberculosis. She was taken to Bamburgh for further treatment and appeared to make some improvements. Sadly, it did not last, and she died on 24th October 1842 at the age of 26. She was buried in Bamburgh churchyard where a monumental tomb was erected in her memory in 1846. On this her effigy is in a recumbent position, hands crossed with an oar by her side embraced by her right arm. Inscribed in the stone is another tribute from the pen of William Wordsworth:

The maiden gently, yet at Duty’s call

Firm and unflinching as the lighthouse reared

On the island-rock, her lonely dwelling place;

Or like the invincible rock itself that braves,

It is 1952 and modernisation is well under way at Longstone. Scaffolding, cranes, piles of rubble and workman’s huts all suggest there is much work being done at the lighthouse.

(ALK archives)

Age after age, the hostile elements,

As when it guarded holy Cuthbert’s cell.

In 1859 a party of Royal Commissioners visited the Longstone lighthouse which they found in excellent order. William Darling again recounted the story of the rescue, pointing out the Harker rock from the tower. He told them that his daughter had died of a decline brought on by an “anxiety of mind” because “so many ladies and gentlemen came to see her that she got no rest.”

Grace Darling had become a national heroine almost overnight. Sadly, it was perhaps because of her deeds of courage and bravery, because of her skill of seamanship, that she suffered such an untimely and premature death. However, such events are now so well documented that her memory will live on, helped by the more tangible remains of the coble that she and her father used which is on display in the Grace Darling museum, while a plaque on the wall of Bamburgh post office reminds visitors that this is the house in which she died.