4

4

DAD

During the thirties, the era of Big Bands, my father and his orchestra appeared in the best hotels, the best casinos, the best dance halls. His records were played constantly on the radio. His distinctive piano style was widely imitated, and it spawned an industry of sheet-music arrangements, featuring his trademark smile and slicked-down hair on the covers. Dad was a star.

All this I took in only obliquely when the Philco radio in the kitchen at Arden was turned on and I would hear a voice say, “And now, ladies and gentlemen…Eddy Duchin and His Orchestra coming to you live from…”

My scrapbooks are filled with letters Dad wrote to me, along with snapshots of him posed at the keyboard in white tie and tails or standing on the bridge of a Navy destroyer in his officer’s dress uniform. I have all the cards that came with his birthday and Christmas presents, everything carefully pasted down by Chissie or Zellie. Most are signed “Wish I could be with you—I love you, Dad.” Underneath is Chissie or Zellie’s description of the gift: a drum, a stuffed dog, red earmuffs with a metal band.

After Dad went off to war in 1942, the radio would be turned on in the late afternoon for the news from overseas. Somehow I understood that he was connected to the reports that would make Frances, the Irish cook, grow quiet or Zellie suddenly stiffen. I was told my father was “in danger.” Zellie was convinced the Germans would be landing “any day on the beaches of Montauk Point,” and she would tell me how brave Dad was. “He’s protecting us from the enemy, but he can’t write us what he’s doing because it’s censored.” I loved that word.

The times he visited Arden before he shipped out, Dad would greet me with a big smile and a kiss and pick me up in his arms. I liked his officer’s hat and his brass buttons, but I could feel he wasn’t at home in the country, and I knew he wouldn’t stay long. We would walk hand in hand through the woods to the lake, and I would be bursting to tell him about the fish I’d glimpsed the day before, but I knew he’d only pretend to be interested, so I kept it to myself. He looked nervous, climbing into the green rowboat, worried he’d get his clothes wet. I don’t remember what we talked about, but I remember feeling uncomfortable.

A couple of years ago, when my band and I were in Florida for a gig, I took the opportunity to explore two parts of my past. One I had known well. The other I had never investigated.

Marie Harriman, me, and Dad at Sands Point.

I had been hired to play for a dinner dance at the yacht club in Hobe Sound. The hostess was an old friend, Toddie Findlay, the daughter of Dwight Deere Wyman, the Deere & Co. heir who produced a lot of Rodgers and Hart musicals in the thirties. Toddie had rescued me after my first marriage came apart by letting me stay at her house in New York. At her request, I had played for the funeral of her first husband, Gubby Glover, out in Moline, Illinois. It was one of the more surreal gigs of my career. Toddie had made a list of Gubby’s favorite songs, and I had played Gershwin, Porter, Berlin, and Rodgers, tears running down my face in a church full of equally tearful nostalgists.

All through my childhood, I spent most of my Christmas and spring vacations at Hobe Sound, staying in Ma and Ave’s big, white oceanfront house on Jupiter Island. A forty-five-minute drive north of Palm Beach, the island had been developed back in the twenties as a winter place by Joseph Verner Reed, a cultivated, wealthy businessman from Denver, and his wife, Permelia Pryor, sister of Samuel Pryor, one of the founders of Pan Am. Over the years, several hundred rich families with sufficient background and character to pass the Reeds’ muster had bought land on the island and built large, discreet winter houses. When I was a child, they were hidden at the ends of long, pebbled driveways bordered by high hedges of hibiscus and sea grape. There was the Yacht Club, the Jupiter Island Bath and Tennis Club, the golf course, the boat docks, the liquor store, and the old movie house, the Tangerine, with Spanish moss hanging from the ceiling. That was it, except for the occasional wildcat prowling about, herons and ospreys fishing, and gulls and pelicans sailing up and down the beach.

Hobe was Never-Never Land. I’d wake at five in the morning and head out across the lawn with my fly rod. At sunrise, I’d be standing in my sneakers, knee-deep in the warm inland waters around the golf course, casting my popping bug for redfish, snook, or sea trout feeding in the shallows.

Ma and Ave had a butler named Hollingsworth—a name Ave could never get right. He’d call out “Hollingshed!” or “Hollington!” or—Ma’s favorite—“Hollywood!” I remember being awakened one morning by a knock and the sound of Hollingsworth’s discreet voice saying, “Sir, the blues are running.” I felt I had died and gone to heaven.

When I was six and had come to Hobe Sound for the first time, my godfather Brose Chambers told me not to pick up anything in the sand that resembled a bracelet with red, yellow, and black bands on it. “That’s what a coral snake looks like, Peter,” he said. “If it bites, you die in less than a minute!” For days I combed the dunes, poking at lizards, crabs, and fragments of turtle eggs, looking in vain for coral snakes.

I doubt if anyone has spotted a wildcat near Hobe Sound in years, except maybe during the summer, when the place is deserted. But when I arrived at the yacht club for Toddie’s party and saw everyone standing around on the sloping green lawn that stretches along the waterway, I thought the only thing that had changed was that the same old people had gotten older. There were the same old tiny lights twinkling in the distance, the same old palms swaying in the breeze, the same old wicker furniture and chintz. One of the old waiters spotted me and said, “Nice to see you back, Mr. Duchin, it’s been a while.”

Standing around with their whatever-and-tonics and munching cheese puffs were people I’d known all my life. Old Joe’s son, Nat Reed, who kind of runs the island, came over and said, “Got any time to go fishing, Pete?”

I embraced Douglas Dillon, President Kennedy’s secretary of the treasury, and Nelson Doubleday came over to chat about our school years at Eaglebrook. All the men were in blue blazers, linen trousers, and tassel loafers. The women wore various shades of pastel and little jewelry.

Shortly after midnight, the band packed up and Toddie and I kissed good night. As I drove slowly down the island, past the little white signs at the ends of driveways saying, “Half Moon Under,” “Faces East,” and “Harlequin,” I felt as comforted as I would have been in the kitchen at Arden, smelling burnt toast.

The next morning I drove fifty miles south to say hello to my father’s younger sister, Aunt Lil. Since the death of her husband, my uncle Ben, a decade before, Aunt Lil had been living in a condominium near Fort Lauderdale. It was a faded, peeling, cinder-block complex where life revolved around the golf course and a swimming pool. There was a golf bag in the corner of Aunt Lil’s living room. Now in her early eighties, as big boned and earthy as my father had been thin and refined, she was doing fine.

As a kid, I hadn’t seen much of Aunt Lil and her family, who lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, but I always associated my visits to them with a kind of earthy comfort. Uncle Ben was a doctor, and there were two children, Susan and Lester, both of whom were about my age. My grandmother Tillie lived nearby, and she would bustle around her kitchen in a loose, flowery dress, preparing the special meatballs I loved. Under a clear plastic hood would be a thick-frosted vanilla or chocolate cake.

My grandmother Duchin was a peasant: gray hair in a bun, rugged, deep-lined face, slightly Oriental features. She was a woman of few words, and she was totally at ease with children. I was fascinated as I watched her big hands kneading and shaping the dough for matzoh balls. My favorite place for a late-night snack is still the Carnegie Deli on Seventh Avenue in New York. I can’t think of anything better for a good night’s sleep than matzoh-ball soup.

Now, over iced tea—“made just this morning”—Aunt Lil reminisced about how the Duchins had come to America. Following in his brothers’ footsteps from the Ukraine, where he was one of eleven children, my grandfather Frank Duchin had gotten off the boat at Ellis Island in the late 1880s and gone to Boston to become a custom tailor of men’s suits. In 1906, he had married my grandmother, Tillie Baron (born Barashevsky), who had also just arrived from the Ukraine. My father, the first of Frank and Tillie’s two children, was born on April Fools’ Day, 1909.

Frank Duchin prospered and eventually expanded his business into a retail haberdashery that supplied many of the uniforms for the Boston cops and firemen. But he suffered from chronic kidney ailments and was often forced to go into a hospital for months. Despite these problems, Aunt Lil remembered a happy, secure childhood. “We never wanted for anything,” she said firmly. “Dad’s condition was diagnosed as a very rare one—leukoplakia. His doctors told him he needed a salt-air climate, so we moved out to Beverly on the North Shore.”

I asked how my father had taken up the piano.

“Our grandmother on Mother’s side had been a piano teacher in Kiev. And there was always a ton of classical music on the radio. Eddy loved it. When he was seven, he took his first lessons from a Mr. Scoville. At thirteen, Mr. Scoville said there was nothing more he could teach him. Take him to Felix Fox in Boston,’ he said. So Eddy went twice a week for a couple of years to Felix Fox. He and Mother always took the streetcar—an hour each way. She waited for him during the lesson. Then she took him home.”

“A real Jewish mother.”

“She knew Eddy had talent. He had perfect pitch. He could hear something once and go right to the piano and play it. But he was lousy with lyrics. His singing was a disaster.”

Me and my cousin Susan with my father’s parents, Tillie and Frank Duchin, in New York in the early forties.

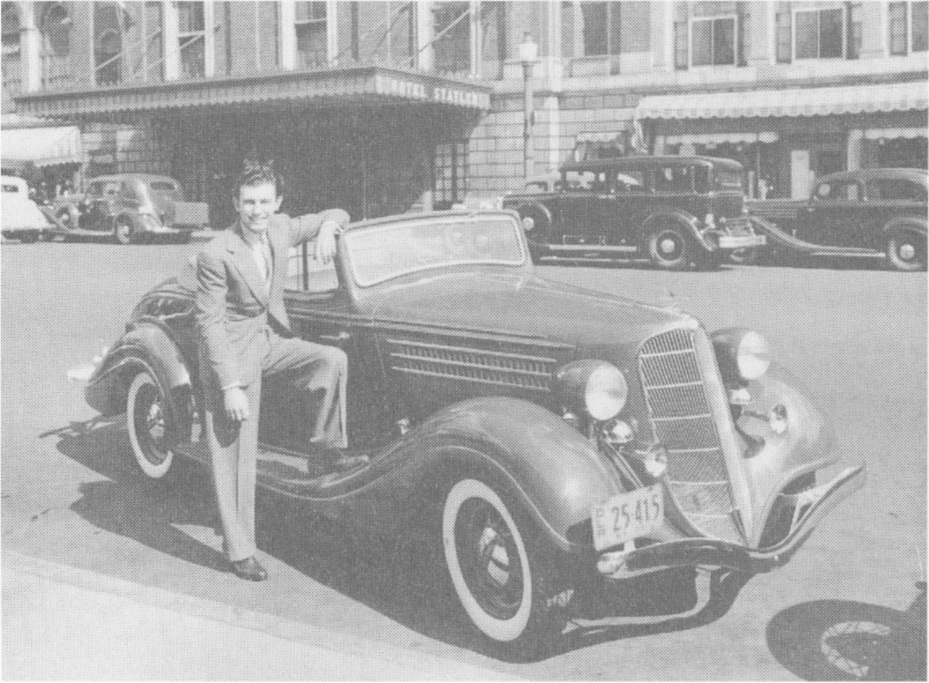

Dad tries out a 1935 Terraplane convertible. He bought his first car, a Peerless sedan, when he was eighteen. He paid for it by playing the piano at Bar Mitzvahs.

“Did he like to practice?” I asked, remembering how much I’d hated it.

“No! He’d rather shoot pool or play basketball. Anything but practice.”

“When did he get serious about a music career?”

Aunt Lil laughed. “When he discovered he could make money from it. By the time he was fifteen, Eddy was playing bar mitzvahs. For his sixteenth birthday, my parents gave him a baby Steinway grand. At eighteen, he was making ninety bucks a week!”

“What did he do with it?”

“Buy a Peerless automobile, that’s what. But Mother and Father didn’t think a musician’s life had any security in it. Since there were a couple of pharmacists in the family, they pushed him in that direction. So right after high school, Eddy went off to Massachusetts College of Pharmacy.”

After a year in pharmacy school, my father organized his first band—piano, violin, and alto sax. That summer he composed the only song he would ever write. It was inspired by a girl he was in love with, and it was called “Don’t Forget About Tomorrow, Though Today May Be Gray.” There were no signs that he was much of a wordsmith. In 1928, between his junior and senior years in college, he was hired for the summer as a rhythm pianist by Leo Reisman, whose band was booked at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York. He returned to college in the fall, got his degree as a pharmacist, and never filled out a prescription. As soon as he graduated, he was back with the Reisman band, this time at the swankiest nightspot in New York, the Central Park Casino.

Designed by Calvert Vaux in the late nineteenth century, the Central Park Casino was situated on the east side of the park, 400 yards off the Sixty-fifth Street transverse. The building had been dark for years when in 1929 Mayor Jimmy Walker and his Tammany Hall cronies decided that the city needed an exclusive nightclub. Walker commissioned Florenz Ziegfeld’s theatrical designer, Joseph Urban, to give Vaux’s building a massive Art Deco face-lift. The renovation featured a spectacular crystal ceiling over the dance floor. Gold murals paneled with black glass lined the ballroom walls. The dining pavilion was done up in maroon and silver. The Casino was an instant smash, and everyone in New York who was anyone came there to be seen and to dance. Mayor Walker and his friends were entertained in private rooms, where many of the city’s business transactions were also said to take place.

On my way down the coast to Aunt Lil’s, I had stopped to have breakfast with Herbert Bayard Swope, Jr., and his wife, Betty, at their waterfront house in Palm Beach. Ottie Swope was named after his father, the famous editor of the old New York World who had made a deal with the financier Bernard Baruch. In return for his making Baruch famous, Baruch made him rich. Ottie had grown up in a huge Gatsbyesque mansion in Sands Point, Long Island, just down the beach from where I’d spent many of my childhood summers in the far more modest Harriman house.

The Swope property was often the setting for one of Ave’s favorite sports, croquet. While he, Ottie, and their friends were engaged in titanic, savage battles with mallets and wickets (Ottie is still one of the country’s premier croquet players), I’d find the Swope grandson, Bayard Brant. The two of us would wander down to the brackish stream leading to the Sound to poke at fiddler crabs or search for eels.

This was in the tail end of the period when the Swope mansion was weekend headquarters for Robert E. Sherwood, Dorothy Parker, Ring Lardner, George S. Kaufman, Moss Hart, Deems Taylor, Alexander Woolcott, Robert Benchley, and the rest of the Algonquin crowd. A principal attraction of the Swopes’ hospitality was their staff—three shifts of servants, on duty around the clock to answer every guest’s need, whether you were playing in an all-night poker game, taking part in an epic croquet match, or just thirsty.

Ottie had been a young man-about-town when my father was starting out at the Central Park Casino.

“Your father,” he recalled, “seemed to me a very strange character, particularly in the early days, when he was only the rhythm pianist. He would sit there silently at the keyboard, looking very self-absorbed. He wasn’t terribly kempt, at least when he was starting out. He had a faint bluish-blackish five-o’clock shadow. He was the kind of man about whom you created a fantasy. For example, was he on drugs? I think one of the things that got him so famous was that he seemed neurotic and indifferent to the room.”

“A touch of Gatsby.”

“Something like that. There was another thing. He didn’t smoke. While the rest of the band went out for a cigarette break, he’d stay at the piano and take requests. All the girls lined up. Your mother was at the head of the line.”

Before long, my father was the Casino’s biggest draw. He wore white tie and tails, with a red carnation for a boutonniere, and was dubbed “the Cocktail Casanova.” His piano style bridged the sharply syncopated music of the twenties and that of the slower, more melodically romantic thirties. By 1931, when he was only twenty-two, he had inherited Reisman’s job, and that year Eddy Duchin and His Orchestra opened the Casino on Labor Day. He had acquired some important fans and patrons. Early on, Averell Harriman had donated a pair of black shoes, John Wanamaker of the Philadelphia department-store family had given him his first dinner jacket, and John’s sister, Mary Louise, gave him a pair of studs. George Gershwin helped him set the seating arrangement for the musicians.

The Central Park Casino in 1929, when it reopened as the most exclusive nightclub in New York. It was the favorite hangout of Mayor Jimmy Walker and his Tammany Hall cronies. My father was the headliner there in the early thirties.

Dad and his orchestra in 1935, two years before I was born. Dad had one of the top dance bands in the country and a string of hit records by then.

John Wanamaker later presented Dad with a Bechstein baby grand. One afternoon as he was walking home from lunch, my father was astonished to see a crane hoisting it through his living room window. The note attached to the piano said,

Dear Eddy, I hope you enjoy playing it as much as I enjoy listening. P.S. Please use the piano-tuning department at my store. Business is lousy!

Today, the Bechstein sits in the living room of my New York apartment.

In those Depression days, show business was one of the few businesses that wasn’t lousy. My father launched his first radio show on NBC in 1933—Pepsodent’s Junis Face Cream program. Two years later, he and the band were signed for the Texaco program, hosted by the comedian Ed Wynn. By then the Casino had been closed down by New York’s park czar Robert Moses, on the ground that it was too elitist to occupy city property.

And by then the Eddy Duchin Orchestra—an eleven-piece ensemble of lead piano, three saxes, a trumpet, a trombone, banjo, fiddle, a second piano, bass, and drums—had become one of the top dance bands in the country. My father and his musicians introduced twenty new songs a month—Gershwin, Rodgers, Berlin, Porter, Arlen (among them, “Stormy Weather,” “I Concentrate on You,” and “Brazil”). Hollywood beckoned, and Dad led the band in Paramount’s Coronado and Republic Pictures’ The Hit Parade. He made one hit record after another. His biggest was “Ol’ Man Mose,” a swing spiritual written by Louis Armstrong. What sent it to the top was the way the vocalist, Patricia Norman, fudged the line “Ol’ Man Mose kicked the bucket/Yeah, man, buck-buck-bucket…,” making the b sound like f. Today, I play “Ol’ Man Mose” at every gig, and it never misses.

My father’s keyboard style was instantly recognizable. He was one of the first bandleaders to take the piano out of the percussion section, where it had been used to pound out the rhythm, and make it the star attraction. His right hand was smooth, rippling, classical in tone. (His signature number was a paraphrase of Chopin’s Nocturne in E-flat.) He favored big, squashy chords—his hands were enormous—that gave an orchestral richness. His left hand was driving and always on the beat.

When my father tried out a new song, he first talked his way through the lyrics so that he would have them firmly in mind. His playing had a nervous intensity, as though he were making the arrangement up as he went along. In 1935, George Simon, a writer for Metronome magazine, gave this description of the Duchin style: “The essence of Duchinesque piano playing [was] ‘whatever he happened to feel.’ Duchin’s piano is one of moods. As he puts it: ‘I close my eyes, hum to myself, and then play whatever I happen to feel inside of me.’ I think it’s the first time that any dance orchestra pianist has adopted that formula—playing what he feels rather than what he sees. It’s inspirational rather than mechanical.”

The reason he played with his eyes closed, my father explained, was for concentration, not effect.

One of his most distinctive trademarks was to switch the melody to the bass clef, crossing his hands and outlining it in dark single notes. He amplified the effect by installing a mirror behind the keyboard to reflect what his fingers were doing—an innovation that later became standard for television pianists. He explained that because he couldn’t sing, he phrased the way a singer like Helen Morgan or Libby Holman “breathed.” In 1934 he told a reporter: “My theory was that vocalists sounded different from one another because they breathed differently—their inflections were different. Therefore, I thought, why couldn’t that be applied to a solo instrument? I began to hum on the melody with a singer’s inflections—I breathed with the piano as I would with my voice. I played louder and softer, just as I interpreted the song through my humming.”

Playing with the inflections of a vocalist, he said, made the listeners want to sing: “And when you’ve done that you’ve won them over, because then they want to dance.” Another of my father’s innovations was his freedom with tempos, which he changed according to the mood and abilities of the people dancing to his music.

By the end of the thirties, Dad was known as “the Magic Fingers of Radio.” His hands were insured for $150,000. Sergei Rachmaninoff once told him he was good enough to play classical music. But how much money did he make playing in a band? the great virtuoso asked. When he heard my father’s answer, Rachmaninoff said, “Forget classical. Stick to what you’re doing.”

I asked Aunt Lil whether Dad’s personality had changed when he became a star.

Her reply was fierce: “No! Eddy was a marvelous son. When he started to make it big, Father got sick again. Eddy said, ‘No more work, Dad, this is it!’ From then on, he put them on an allowance.”

“Did he have a problem being Jewish?”

“Not that I ever saw. We were all crazy about Marjorie—she was so sweet on him—so there was no problem from us. The only time it ever came up was when he got married again, to Chiquita, who was Catholic. The wedding was in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, and at the last minute my mother refused to go. Eddy tried to change her mind, but she wouldn’t budge. She gave her blessing, but she and Dad stayed in the hotel.”

“Was Eddy embarrassed about his parents?”

Aunt Lil paused. “For only one thing. Did you know your grandmother never learned to read or write?”

I didn’t—and was astonished I didn’t.

“It was the family secret. She was very ashamed of it. I’ll never forget when Eddy was playing the Persian Room and we all came down to New York. As usual he got us the best seats in the house, right up front. When the captain came over with the menus, Eddy jumped up and yelled, ‘No menus! I’ve ordered the meal!’ It was because he didn’t want Mother to be embarrassed when she couldn’t read the menu.”

“I gather he had a bad temper.”

Aunt Lil shrugged. “Most of the time he was charming. But once in a while he would snap. I don’t know why. I once saw him throw a basket of rolls across the room because the waiter brought him white bread instead of Rykrisp. Another time, the hotel operator called while he was taking a nap, and he was so mad he jerked the phone out of the wall.”

I remembered something that had happened when I was about three or four. Dad had come out to Arden one Sunday, and we were down at the boathouse: Zellie, Ma, her daughter Nancy, and the two English girls, Betty and Ninky, whom the Harrimans were boarding during the war. I was obsessed with a bowl of peanuts on the table. I loved biting the shells in two and getting the little nuts out of their hiding places. I had gone through most of them when I heard my father’s voice: “Peter, I told you to stop eating those peanuts! You’ve left nothing for anyone else! You’re to go back to your room right now and stay there! Mademoiselle, take Peter home!”

And so I was led away in tears, banished to my room in the cottage. Some time later, Nancy came in and found me clutching my favorite stuffed bear, the gray and white one with the ripped ear. She lay down beside me, propped my head against her soft arm, and opened my favorite collection of stories, Kipling’s Jungle Book.

Before long, I had calmed down, transported into a world of my own by the tale of a wild, naked Indian boy named Mowgli who loses his parents and gets taken in by the Seeonee wolf pack, in whose protection he is taught by Baloo the bear and Bagheera the black panther how to hunt like an animal, how to speak to the wild bees, and how to master all the other “wind and water laws” of the magical jungle.

Arden, the Harriman family mansion, sat on a hill on a ten-thousand-acre estate.