7

7

AVE

My earliest image of Ave is that of a tall, lanky man, moving purposefully and gracefully against the wintry landscape at Arden. Ave: remote but sharply etched, always off somewhere even when he was sitting right in front of you, poring over the morning newspapers.

During the war when he was running the Lend-Lease program in London, and later when he was ambassador to Moscow, I saw very little of him. But when he did drop in at Arden, I knew that “the boss,” as Bill Kitchen called him, had arrived.

Suddenly, everything would speed up. Horses would be readied in their stalls in case Ave wanted to ride out into the fields. The old Pontiac station wagon would be brought out into the driveway, all cleaned up and polished with Bill’s chamois. Ave would step out of the Lincoln Zephyr in his double-breasted suit, button-down shirt, tie, and shiny black shoes and would disappear into the cottage, only to reappear minutes later in his country clothes: a raggedy V-necked terry-cloth pullover of dark or light blue, creaseless tan corduroys, sturdy, rubber-soled brown shoes. The servants would be greeted with a smile and a brief hello. I would get a light kiss on the cheek and “Hello, Petey, how are you doing?”

In my scrapbook is a snapshot of me when I was five or six, sitting with Ave in a horse and buggy. It must have been one of the first times he and I went on an outing together. I’m wearing a tie, which means it was Sunday and we were on our way to Dr. Dumbell’s service at St. John’s, the Arden chapel. Ave is in country tweeds, wool tie, and jodhpurs. I look happy and proud: the little lord of the manor.

Whereas Ma’s day would start around noon with her breakfast tray and the Times crossword puzzle in bed, Ave’s would begin hours earlier with the morning news. I would have gotten up even earlier, and after I was dressed I’d rush over to his cottage. If the weather was fine, he’d be sitting on the screened porch at a plain, painted white table, listening to the radio and reading the New York dailies, one by one. He’d be wearing his tattered light blue bathrobe, leather slippers, and blue pajamas, all from Brooks Brothers. I’d enter without knocking and say, “Hi, Ave,” give him a kiss, then go into the kitchen and ask the cook for an egg or—a special treat—Irish oatmeal with melted brown sugar on top.

Then I’d sit myself very quietly at the other end of the table. After a minute or two, during which I’d concentrate very hard on not moving a muscle or making the slightest sound, Ave would look up and say, “Good morning, Petey.” Then he’d go back to his paper, one ear tuned to Quentin Reynolds or Edward R. Murrow, whoever was giving the news from Europe. The only break in his concentration would come when one of the Labs, sitting patiently at his elbow, growled or put a paw on his knee. Without taking his eyes off the paper, Ave would insert a piece of toast into the salivating jaws.

W. Averell Harriman with Churchill and Stalin in August 1942. Ave was representing President Roosevelt at a meeting called by Stalin to discuss the war. He was made ambassador to the Soviet Union the following year.

I would eat my egg in silence. Finally, the last paper would be folded together. Placing it on the pile to his left, Ave would glance up and announce his agenda for the morning. He always had an agenda. Then he’d say, “It’ll take me an hour. After that, why don’t we go for a ride?”

I was probably six or seven when I began thinking of Ave as the father I wished I had. I knew I had “Dad,” but Ave, who clearly operated on a more commanding level than anybody else, was the father I wanted. Until my father’s reappearance in my life after the war, Ave seemed to encourage this relationship. Indeed, more than once over the years, his two daughters, Mary and Kathleen, told me they’d always felt that I was the son “he wished he’d had.” If so, Ave was happy to keep it from becoming a reality. As I would later understand, making me something beyond a fantasy son would have entailed a more emotionally complicated relationship than he was capable of. It’s significant that his two daughters never called him anything but Ave or Averell—never Dad or Father.

As long as I was doing something with Ave, I felt comfortable. He didn’t like me just hanging around; he really didn’t like anyone just hanging around. The only spontaneous moment of intimacy with him I can recall occurred one day when I was still in short pants. Walking past the open door to his bathroom, I saw Ave leaning over the sink and looking at himself in the mirror. I ventured in. I had never seen him like this before. He had white cream all over his face, and he was stroking his cheeks with a strange, shiny tool.

I tried to make myself invisible.

“Hello, Petey,” he said, not smiling. “What are you doing here?”

“Hi, Ave.”

Silence. Stroke, stroke. I knew I was in a place where I shouldn’t be, but I was too frightened and too fascinated to run. Suddenly, Ave crouched down and put his face with the white stuff on it close to mine.

“What’s that?” I asked, pointing to his face.

“It’s called shaving cream, Petey.”

“What’s it for?”

“It’s for shaving,” he said. “Shaving is what men do when they grow hair on their faces. When they get older.”

“Can I try?”

He thought about it. Then he picked up a tube and squirted some of the white stuff into his hand. “Here,” he said, kneeling down and slathering it on my face. Slowly, he stroked the razor down my cheek. “There,” he said. “That’s how you shave. Someday you’ll do it yourself.”

Then it was over. Abruptly, he rose to his full height, resumed his position in front of the mirror, and said, “Run along now, Petey.”

Never had I felt closer to Ave.

I’ve always thought Ave really preferred animals to people. He loved to command, and the animals loved to obey. “Heel!” he’d say to a dog. When the dog did, a smile would spread across Ave’s face. There were always dogs around. Ma had her wirehaired dachshunds and, later, Jack Russell terriers. Ave had his Labs. Once, down in Hobe Sound, he saw one of his aides throwing a stick on the beach for a favorite Lab named Brum. “Goddammit!” I heard him mutter. “No one should ever play with another man’s dog!”

This same aide was later fired because he had the temerity to underscore things he thought Ave should take note of in the newspapers. “How the hell would he know what I should read,” I’d hear Ave growl when he picked up his morning Times and found it underlined in red crayon.

I’ve never been more terrified in my life than the morning Ave lost his temper over a dog. I was five or six, and I’d headed over to his cottage because he’d promised to take me out on the lake. While Ave was immersed in his paper, I sat there, whittling a stick. One of his Labs came over and started growling, and I poked him on the head several times.

Suddenly Ave was out of his chair. Grabbing the stick, he whacked me on the behind, then on the back of my legs. “Don’t ever strike an animal like that!” he said in a voice I’d never heard before.

I burst into tears and ran to the other cottage, where Frances was baking bread. Zellie heard my screaming and came in.

“Ave hit me!” I wailed.

“But that’s not possible!” Zellie said. “What did you do?”

“I hit Scotch.”

“That is very bad!”

I let out a louder wail.

Ave walked in and put a hand on my shoulder. “Petey,” he said, “I hope you learned your lesson.”

I nodded.

“Do you still want to go to the lake?”

“Buggy ride.”

“Get ready.”

Zellie suggested I write Ave and tell him how sorry I was that I’d hit the dog. She helped me write the note, which I signed, “I love you, Ave—Peter.” Together we took it to his bedroom and placed it on his pillow. The next morning, I ran over to Ave’s, took my usual place at his breakfast table, and waited for him to say something about the note. He didn’t. For days I waited, biting my tongue to keep from asking if he’d read my note. If he did, he never said a word about it. He had moved on to his next agenda.

Ave was the most determined man I’ve ever known. In his memoir In Search of History, Theodore H. White observed that “once Harriman was wound up and pointed in the direction his government told him he must go, he was like a tank crushing all opposition.” His doggedness may have come from the fact that, for all his wealth and privileged upbringing, he had had a lot to overcome: a childhood stammer, sickliness, and, most of all, an overbearing and demanding father. When he was at Groton, young Averell had to send home weekly reports on his progress. His father also made him contribute a big chunk of his allowance to put a less fortunate boy through school.

Ave had to be the best at whatever he did, whether it was making money; playing polo, croquet, or bridge; shooting birds; being an ambassador; or advising presidents. He had to win. The last time he and I went duck hunting was down in Hobe Sound. Ave had just turned seventy-five, and he probably hadn’t held a firearm in twenty years. But he shot like a man fifty years younger. With every flight of ducks, he’d calmly raise his gun, take aim, and hit the target. Occasionally, in a breach of duck-shooting etiquette, he’d bring down a bird that was clearly on my side of the blind. “Damn,” he’d say, “I guess that was yours. Sorry.” Then he’d do the same thing again.

From the beginning, I sensed Ave’s competence: how, with the slightest tug or tap of his whip, he could direct a horse to speed up or slow down, turn or stop. Later I learned that he had once driven his own trotters at the famous track in Goshen, New York. He was a wonderful teacher. When I turned eight, I graduated from my little pony to a full-size horse. Ave would mount one of his two huge horses, Fact and Boston, that had been given to him by Stalin, and stand in the field for an hour or more, appraising my figure eights and my posting, raising his voice a little when I repeated a mistake: “Petey, once again! Relax the reins! Give him a kick with the outside foot!”

When I got a little older, he took me out on the polo field at Arden, handed me a small mallet and ball, and showed me how the two should connect. Every time I hit a good one, he let out a whoop of joy. Later, when I graduated to croquet, the sport that aroused his competitive instincts the most, I realized how much winning meant to him—and how it didn’t mean that much to me. Ave’s favorite way to win at croquet was with one great shot at the end. Triumphant, he’d murmur, “Not bad,” and walk away from the group. If he lost he’d say nothing. But for the rest of the day, you’d know about it.

It says a lot about Ave that while his croquet buddies maintained impeccably manicured English courses, his courses at Sands Point and Hobe Sound were of his own eccentric and diabolical design. Their terrains were rutted and thick with crabgrass. They had no boundaries. In Hobe Sound, the most treacherous side of the course was a jungle. In Sands Point it was Long Island Sound. Nothing gave Ave more pleasure than to hit another player’s ball so that the opponent would take two turns to get back in play. Most of his croquet friends hated playing on the Harriman courses, which pleased him enormously—and gave him a distinct psychological advantage. Not until the British prime minister Anthony Eden came to visit in Hobe Sound did Averell have the course properly rolled. Ma, who was breakfasting by the pool when the steamroller arrived, hooted with laughter at Ave’s putting on the dog for “those damn Brits.”

Ave and me at Arden. He was a somewhat remote figure of absolute authority for me. He and I didn’t go out in the buggy very often. In the photograph above we’re probably on our way to church in the Arden chapel.

Ave had an aristocrat’s sense of service. He never actually sat me down for moral instruction, but in offhand remarks he let me know the importance—if you were to be regarded as a “gentleman”—of “giving back” as much as you “took.” How many times I heard him say: “He’s a sweet man, but he doesn’t do a damn thing.” Or “I’ve known that fellow for a long time. He’s a Republican who does nothing but eat and drink. He should have learned that he could have had a helluva lot more fun as a Democrat. As I have.”

It was antiquated fastidiousness, not snobbery, that prompted Ave to say things like “Never have a meal with your lawyer, Petey. You don’t want to get too close to him. Keep it on a business level.” It wasn’t that he looked down on people who earned their livings as lawyers. It was simply that anyone he paid to perform a service for him—lawyer, doctor, tailor, barber—he regarded as a “tradesman.” There was no hierarchy among them. In Ave’s eyes, Bill Kitchen was as important as the personal financial adviser I only heard him refer to as Cook. He treated them all with equal courtesy, but he would never dream of setting foot in their domains. If they had business with Ave, they came to him.

You never saw Ave ever actually deal with the physical fact of money—a subject he hated. He never carried cash, and if you went with him to a restaurant where he wasn’t known, you’d end up with the check—to be reimbursed later only if you remembered to notify Cook of the amount.

Four times a year, Cook would arrive to give his update on the Harriman finances, a topic so sizable that the documents relating to the family’s fiscal transactions were said to occupy the better part of a floor at Brown Brothers Harriman, the family banking house in lower Manhattan. Ave was utterly bored by these meetings and would enter and leave them in a cloud of irritability.

One of his old friends, the publisher Harold Guinzburg, who founded Viking Press, once remarked to his son Tom and me that he’d never understood what having real wealth meant until one day when he was breakfasting with Ave. “We were both reading the papers,” Harold recalled, “and I was looking at the stock quotes on the business page. I happened to own a thousand shares of Union Pacific and to my great delight saw that it had jumped two points—a gain of two thousand dollars. Averell, of course, owned at least a million shares, which meant a gain of at least two million dollars. ‘Jesus, Averell,’ I said. ‘Union Pacific is up two points.’ Without taking his eyes off the newspaper, he replied, ‘That’s nice.’ ”

Unlike most rich men today, Ave had no interest in displays of wealth. From time to time, he bought a great painting or great piece of furniture. And of course he always had his town clothes made by the tailor who came to the house. But he was more comfortable in his Brooks Brothers country rags, which he wore till they were in shreds. And he was most at home in modest surroundings. As a diplomat, he had a legendary ability to live out of a suitcase.

The house where I spent virtually all of my childhood summers—Ave and Ma’s place in Sands Point, Long Island—was sandwiched between the huge Swope mansion and the Guggenheim mansions (one of which is now an IBM corporate country club). Compared with its neighbors, Ave’s place was a shack: a one-floor, rambling beach house. It had been built as a place simply to change clothes in when he was on Long Island to play polo at the Meadowbrook Club. Slowly he had enlarged the house, adding a pool, a croquet course, a tennis court, and a dock.

In the 1930s, when he was working on Wall Street, Ave would leave the house in his dressing gown and walk across the lawn to the dock, where he would board his motor yacht, Spindrift. By the time his valet had shaved and dressed him and served him breakfast, the boat would be pulling into the pier near his offices.

Sands Point was modestly staffed. The only permanent help was Mr. Phillips, the Scottish caretaker, who lived on the property with his wife. In June, Ma and Ave would arrive with Vicky, Ma’s maid; Jeanne, the French cook; and a couple of maids from New York. Mr. Phillips was a wonderful gardener, a jack-of-all-trades with a deeply lined, leathery complexion. One of my scariest moments as a child was seeing him struck by lightning when he was out on the lawn one day during a thunderstorm. It illuminated him like a creature from Mars and knocked him to the ground. I rushed out, but he had gotten up and was angrily looking around for his pipe. He wasn’t hurt, but his pipe was destroyed.

Mr. Phillips’s passion was fishing. When Harry Whitney and I were lucky enough to go out with him, he’d row us back and forth in the quiet of the evening, pipe clenched between his teeth, filling our heads with the lore of Scottish history, Scottish clans, Scottish wars. We’d troll long sandworms, dug up that afternoon on the beach, or cast top-water plugs. Striped bass were plentiful then, and it was not unusual to pull in a couple of twenty-pounders.

My record was a forty-three pounder, which took me—at the age of ten—more than an hour to land with the help of Harry, Mr. Phillips, and his Irish setter. After the grueling fight, we carried the monster from the rowboat up to the lawn behind the porch, where Ma and Ave were playing bridge with their neighbors George and Evie Backer. Hearing our yells, they rushed out. Mr. Phillips shone his flashlight on the great fish, which was nearly as big as I was. Everyone gasped. My face was as hot as a poker. My bare toes clutched the grass.

The topper was when Ave came over, gave me a big kiss on the cheek, and said, “Petey, this is the greatest fish I’ve ever seen! How grand that you caught it! Tell us about it!” Mr. Phillips and Harry beamed like proud fathers, the Irish setter circled the fish, and Ma announced that we’d have a dinner party the next day in the fish’s honor. I wept with pleasure.

I loved Jeanne, the cook, as much as Mr. Phillips. She was a strong French woman, always dressed in a white uniform, except on her days off, when she’d put on a very severe suit and a hat with a huge pheasant feather. I loved sitting around the kitchen, watching her work. After breakfast, when the tide was dead low, she’d take me down the beach to the flats in front of the Swope house, pitchfork in hand. There we’d dig up buckets of steamers, to be eaten at lunch. Jeanne would wade out along the dock and pull bunches of fresh blue mussels from the pylons to make one of her fabulous marinières or poulettes.

Ma and Ave had still another house, the Harriman cottage in Sun Valley. It was a plain concrete structure with six bedrooms, all modestly furnished and functional. When I was eight, we went to Sun Valley for Christmas.

Ave appeared at dinner in Austrian lederhosen. I thought it the strangest costume I’d ever seen. But, on reflection, this Alpine getup was characteristic of Ave’s custom of wearing a different “uniform” for each of his environments: pinstripes for Wall Street and Washington; old khakis and riding clothes for Arden; baggy shorts and polo shirts for Hobe Sound and Sands Point. Over dinner, he told me how my mother had been a “great help” to him in decorating Sun Valley’s lodge and many of its rooms. It might have been the first time he had ever brought up the subject of my mother to me. I felt a little uneasy and eager to hear more.

“After dinner,” Ave said, “I’m going to show you the room I named after her.”

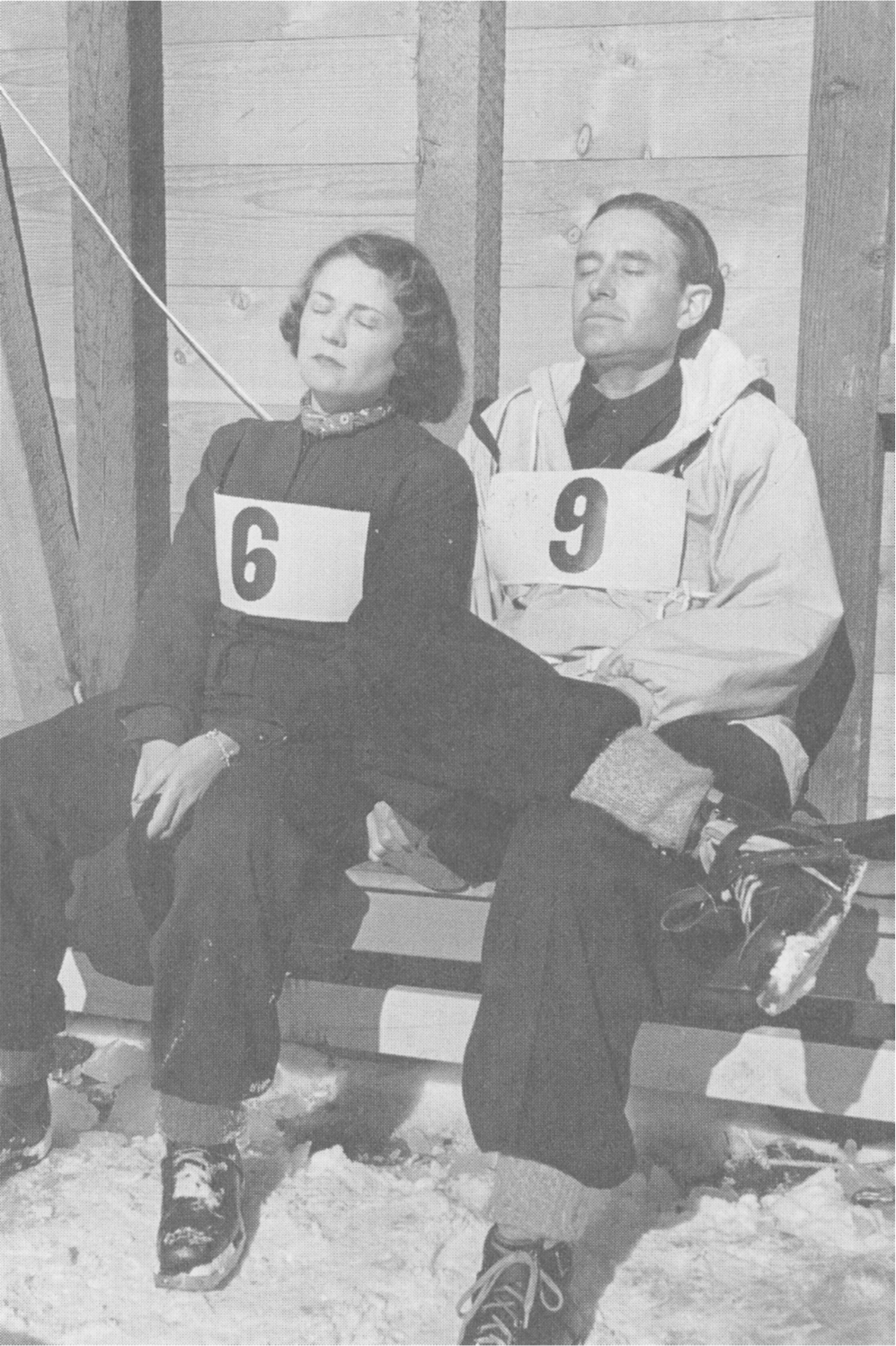

Ma and Ave in Sun Valley in 1937, the year I was born.

I couldn’t understand what he was talking about. A room named after my mother? It turned out to be the bar—a long, rectangular room, rustically furnished, with pictures of celebrity skiers on the walls. Over the front door was a plaque that read THE DUCHIN ROOM.

From that evening on, while the others were floating around the huge heated pool after a day of skiing, I’d sneak into the Duchin Room to gaze at the plaque. The day before we left, I said to a couple of buddies, “I want to show you something.” When I pointed at the plaque, one of them said, sounding not terribly impressed, “Oh, my parents come in here all the time. They call it the Dooh-Dah Room. They say it’s named for your father.”

“No it’s not!” I shot back. “It’s named for my mother!”

Ave was the cheapest man I’ve ever known. One of Ma’s favorite stories was about a Sunday after the war when she and Ave were in Paris. Early in the afternoon, Ave thought he’d stop by the Orangerie to look at one of the Cézannes he and Ma had lent to the gallery. He took along his briefcase, filled with Marshall Plan papers. At the museum, he wandered over to the Cézanne and was standing there, gazing at it, when an attendant came up and said, “Excuse me, sir, the entrance fee is two hundred francs.” Ave reached into his pocket and came up empty-handed. “I’m very sorry,” he said and walked out.

It was a beautiful day, so he told his driver to take him to the Bois de Boulogne. Spotting a vacant bench, he sat down and spread out his papers. After a minute, an old crone appeared and said, “That will be twenty centimes [about two cents] for the bench.” Ave again searched through his pockets. Again he came up empty.

“I’m very sorry,” he said. Putting away the Marshall Plan, he got up and told the driver to take him home.

“Back so soon, Averell?” Ma said.

“Yes,” Ave replied. “Paris has become so damned expensive these days!”

Ave had no gift for small talk. I can’t remember him ever making a casual remark, not even about the weather. But he did make a point of answering whatever anyone asked him, especially if it had to do with a historic event in which he had played an important part. He didn’t embellish his stories with much human detail, but when he did, the detail stuck. I once asked him what Stalin had been like at the Yalta Peace Conference. “While Roosevelt and Stalin were talking,” Ave said, “I couldn’t help notice that Stalin was doodling. I looked over and saw that he was drawing a wolf.”

He was immensely self-involved. One night, my first wife, Cheray, and I were in our bedroom at Hobe Sound when Ave burst in without knocking. He was waving what looked like an old magazine. “Look at this!” he roared, oblivious of the fact that we were undressed and groping for our bathrobes. “It’s the first nice thing I’ve ever read about my father!”

“Gee, that’s great, Ave,” I said.

He handed me an ancient monograph about a steamship trip to Alaska that E. H. Harriman had organized for his family and thirty leading scientists in 1899. Not surprisingly, the writer, John Muir, had produced a highly flattering piece about his host. Ave was so thrilled he had 500 copies printed up and sent to friends.

Such emotional displays were rare. In fact, I can recall only two occasions when Ave really lost his cool. The first was at a dinner party Cheray and I gave in 1966. We had just moved into our house on East Seventy-first Street, and we had gone to a lot of trouble to make things right. Besides Ma and Ave, the guests included their Sands Point neighbors Ed and Marian Goodman, and George Ball, who would soon resign as undersecretary of state over his opposition to America’s involvement in Vietnam. Toward the end of dinner, Marian, who was seated next to Ave, casually remarked, “I certainly sympathize with those boys who don’t want to go to Vietnam. Who would want to give up his life for a cause that doesn’t make any sense?”

Ma and Ave during his successful campaign for governor of New York in 1954. I think he didn’t really appreciate Ma until he saw how great a campaigner she was.

Ave turned white. “You’re a traitor!” he nearly yelled. “You’re a traitor to your country to talk that way!”

There was a terrible silence. To smooth things over, I said, “For God’s sake, Marian, don’t take it seriously.”

Fortunately, it was time for the men and women to separate, as they always did after dinner in those days. Marian went home without saying good-bye to Ave. The next day he sent her some flowers and a note:

Please forgive the misunderstanding. I’ve always been for the eighteen-year-old vote.

“It was completely baffling,” Marian recalled. “It wasn’t a real apology, and of course it had absolutely nothing to do with what we’d been talking about.”

A year later, after Ave had belatedly switched positions on the war, he and Ma were throwing a dinner party in Sands Point. Among their guests were the publisher Bennett Cerf and his wife, Phyllis. After dinner, Phyllis, Ave, and a few others went out to the porch, where the conversation turned to Vietnam. Phyllis, who was never shy with an opinion, began needling Ave about why it had taken him so long to become a dove. Patiently, Ave answered that if he had broken too soon with the Johnson administration, he would have lost influence in the inner circle. That wasn’t good enough for Phyllis, who persisted until she was all but calling him a war criminal.

Suddenly there was a sharp sound. Ave had slapped Phyllis across the face. This was followed by a dreadful silence, with Ave staring at his hand as though it were someone else’s. Bennett just sat there looking sheepish.

The battle was over, and Ave and Phyllis fell all over each other with apologies. But nobody who was there ever forgot that slap.

Ave remained a father figure for me all his life. He was the man who would give me the news that Dad had died. He would attend my graduations from Eaglebrook, Hotchkiss, and Yale. He was always ready with advice, emphasizing that it was wise to get as broad an education as possible, to study ancient history, philosophy, and art as well as the modern stuff. Usually, he ended such conversations with “Don’t waste your time playing bridge, which is what I did too damn much of at Yale.”

When Skull and Bones, Ave’s secret society, made overtures to me (no doubt instigated by him), I said I didn’t believe in the elitism of such organizations. Ave was so furious he refused to speak to me for a month. It was as close as we ever came to a real falling-out—rivaled only by the rage I sent him into when I told him, some years later, that I was supporting George McGovern for president. Ave called the idealistic senator from South Dakota “a wet smack,” whatever that meant.

Except when Ave was angry, he was emotionally remote. But on the rare occasion when he managed to let you know that he did care about you, your self-esteem jumped a notch. In Ave’s hands, the world seemed shapable. He looked at things in a big way. He acted in a big way. And I wanted to measure up.

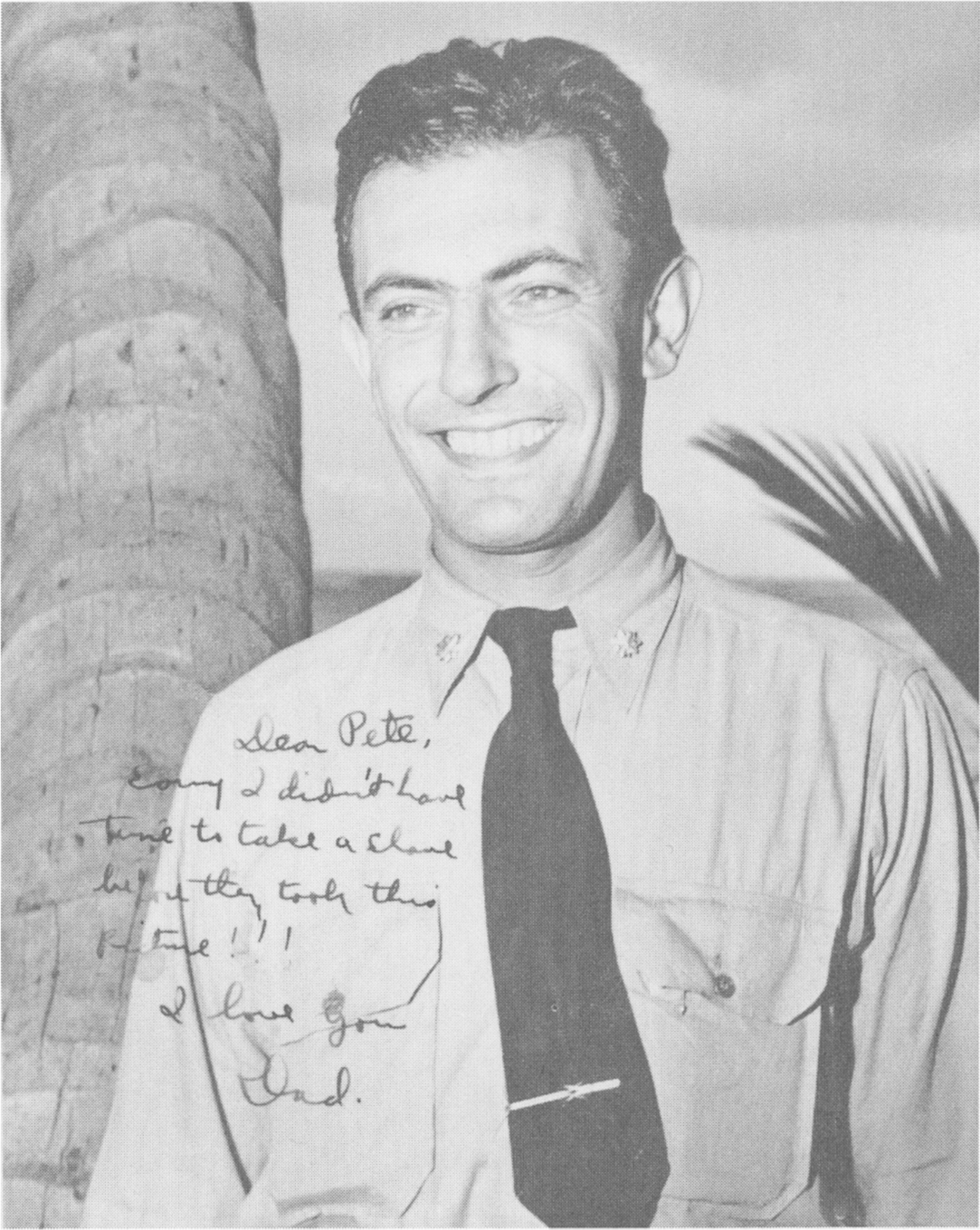

Dad as a naval officer. He chose combat over entertaining the troops.