9

9

“WHO’S PLAYING CLARINET?”

The first really close friend I made of my own age was a kid named Maitland Edey, who arrived at Eaglebrook in the eighth grade. Right away I spotted him as a maverick. Even though he was a fairly big guy with good coordination, he didn’t go out for football like everybody else. Instead he signed up for soccer, which in those days was for weenies. Mait had a round face and a cowlick a mile long. He wore glasses and had an unpredictable, contagious laugh. There was an interesting look in his eyes, slightly amused and faraway. This guy’s a little different, I thought. Like me.

Mait was assigned the room next to mine, and I got to know him better. I liked his honesty, his plain, worn clothes. I liked it that he was so articulate. Before long, we got to talking about things I’d never discussed with anyone my own age before. We were both fascinated by The Nature of the Universe by Fred Hoyle, and we’d sit outside on the hillside and ponder the stars, planets, and constellations, wondering how they all came to be there and whether such a thing as infinity really exists.

We talked a lot about religion. We read aloud from the Greek myths. Our favorite was the story of Ulysses, which we loved for its adventures of survival against the odds and its image of Penelope, the wife of infinite loyalty—our ideal woman. Mait compared his dalmatian, Ace, with Ulysses’ dog, Argus, who had been the only one to recognize the wanderer when he finally returned home. I yearned for a dog.

Mait didn’t give a damn about making an impression, and he seemed so much more in touch with important things than I was that I felt like an idiot. But after a while, I opened up.

One day he said, “I suppose I’m an atheist.”

I was shocked. “I’m more a pantheist, I think,” I said. “I mean, I feel that if there is God, He is in nature and He’s a part of all things in nature.”

“Well,” Mait said with a wry smile, “which came first, God or Nature? Or was it Man who created God to explain the mysteries around him?”

I don’t remember my answer, but I remember that our adolescent probing into philosophical issues continued—along with our discussions of the mystery of girls. Most of all, we talked about music, especially jazz.

Even though I hated to practice the piano, I had a good ear—a gift inherited from my father, perhaps. I’ve never been terribly good at reading music. I would hear one of the hit songs on the radio—“Ain’t Misbehavin’,” “The Naughty Lady of Shady Lane,” “Walkin’ My Baby Back Home”—and I’d go to the piano in the lodge and pick through the melody, trying to add the appropriate harmony.

My best friend at Eaglebrook and then Hotchkiss was Maitland Edey. We listened to jazz records endlessly, talked about girls, and took motorbike trips through Europe in the summer. I even moved in with his family for a while. In this photograph we’re at Eddie Condon’s jazz club in New York, listening to Dixieland.

One day that semester, a classmate, Fred Waring, Jr., the son and namesake of another famous bandleader, heard me fiddling around and asked if I’d like to join a Dixieland group he was organizing. I shrugged it off, thinking I wasn’t good enough. Fred said that one of the masters had told him that putting a band together would get us invited to girls’ schools. That did it. I joined my first band.

There were six of us: besides Fred, who was a damn good trombonist, there were a trumpet player, a drummer, a clarinetist, a bass player, and me. We got our material from the wife of the school band director, Archibald Swift, who lent us sheet music of popular tunes from which we’d improvise our primitive Dixieland arrangements. Mait, still a new boy at school, would sometimes linger in the lodge to listen to us practice.

One afternoon, back in my room, I got a knock on the door. It was Mait. “You want to hear something great?” he said.

I followed him into his room. There, neatly stacked on a shelf, was the biggest collection of records I’d ever seen: two dozen long-playing albums featuring Louis Armstrong and the Hot Fives and Sevens, the New Orleans Rhythm Kings, the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, Jelly Roll Morton, Bix Beiderbecke, and on and on.

“Listen to this.”

He pulled down an Armstrong album, lifted the lid of his record player, and lowered the disk onto the spindle. He lay back on the bed.

While I perched at the foot of it, “Lonesome Blues” filled the room. I’d been an Armstrong fan for years, but listening to him with someone else was a whole new experience.

Mait asked, “Guess who’s playing clarinet?”

My first band. Me, Mait Edey, Dave Ross, and Roswell Rudd at Hotchkiss.

I had no idea.

“Johnny Dodds.”

I nodded.

“Who’s the drummer?”

“Beats me.”

“Baby Dodds. That’s Johnny’s brother. Ask me who’s on piano.”

“Who’s on piano?”

“Lil Hardin Armstrong. That’s Louis’s wife—she also wrote the tune. Banjo?”

I shook my head.

“Look at the album.”

I read the name out loud: “Johnny St. Cyr.”

“Right!”

So began a game that continued throughout our friendship—two years at Eaglebrook, three years at Hotchkiss, vacations from college. As our record collections grew larger, the hours got longer as we’d sit glued to the phonograph, quizzing each other about who was playing what instrument. Our taste expanded from Armstrong and Bix to Teddy Wilson, Billie Holiday, and Benny Goodman, and eventually to Thelonious Monk, Charlie Parker, Dizzy Gillespie, and Miles Davis.

Years later, when Mait and I were touring the south of France on Lambrettas, we were circling through the town of Juan-les-Pins one evening, looking for girls, when we squealed to a stop. “Sidney Bechet!” we both exclaimed. There in an open tent in the town square was the great Bechet, one of our real favorites, soaring on his soprano sax. It was beautiful beyond anything we’d ever experienced.

Mait loved the outdoors as much as I. We’d go on long walks in the woods around Eaglebrook and just talk—about girls, about things we’d read. Most of all, we’d talk about who was the better pianist: Jelly Roll Morton or James P. Johnson? Earl Hines or Fats Waller? “The Boss,” of course, was Art Tatum.

We had the same sense of mischief. We’d sneak into the school kitchen and steal big cans of tuna fish rather than eat the usual glop. We had our own names for each other and our own language. He was Ede. I was Duch. People who didn’t appreciate music and poetry were “apes.” We called creative writing “waxing.” If one of us suggested a walk in the woods, it was “Let’s go dig!” One afternoon we hollowed out some corncobs, filled them with the corn silk, inserted a little wooden tube in each cob, and struck a match. Then we inhaled. Then we got sick.

The Easter vacation after Dad died, I went down to Hobe Sound to stay with Ma and Ave. There I fell in love for the first time. Her name was Paula Denckla. She was a wild-looking girl, four or five years older than I was, with an enormous mane of black hair. For days I watched her from afar, casting long glances and getting nowhere. Finally, I made my move.

One night, during a dance at the beach club, I got myself included in a group of older kids who were leaving for a party at Paula’s. Someone suggested a midnight swim. I charged into the ocean with the others, splashed around, and climbed out looking for Paula—only to discover that she and her friends had vanished into her mother’s house, without a nod at me. I sat down on the sand. I was thinking I’d better go home when I heard a voice next to me.

Her name was Holly, and she was a year or two older than her friend Paula. She was blonde, athletic-looking, and very tanned. When she asked what I was studying in school, I said, “My studies are over.”

She looked doubtful. “What? You’re not in school?”

I was off and running. “Well, I go to Yale in the fall.”

“That’s wonderful. What do you plan to major in?”

“Music.”

“Oh, that’s right. Your dad was Eddy—” She stopped.

I’d heard this a hundred times before. “That’s OK.”

Her eyes sparkled in the moonlight. I reached out and touched a bare leg…a soft hand.

“You must feel so awful….Paula told me…”

“Yes…”

I kissed her. She kissed me back. Then she pulled away.

“No. Not here. I have to get back.”

I saw Holly several times again that vacation, but never alone. Back at Eaglebrook, I wrote her passionate, ridiculous letters. Mait and I would lie around, leafing through poetry books, lifting things from Millay, Byron, and Shelley. I got one breezy reply from Holly. She said she’d be starting a job in New York City in June. In other words, I was free to call.

The fact of my father’s death didn’t really sink in until my graduation from Eaglebrook that spring. Chiq, along with Ma and Ave and the Stralems, came up to see me get my diploma, and they were all immensely supportive. But what I felt most was my father’s absence. All my classmates were surrounded by real fathers and real mothers—people who had the same last name when they were introduced. The presence of my weird little “family” was gratifying, but it was still weird.

I thought of the time before Dad had gotten sick when he’d come up to Eaglebrook and given a concert. When he sat down to play, he made me cringe with embarrassment. “Peter asked me to knock out a few tunes for you kids,” he said, “and I didn’t want to get in Dutch with him, so here goes!” I remembered wishing his piano style weren’t so frilly. Why didn’t he punch the keys like Count Basie? Why didn’t he swing? But he made a huge hit, and afterward my buddies came over and clapped me on the shoulder and said, “Your dad’s really great!”

Thirty-five years later, when my younger son, Colin, was at Eaglebrook, I played in the same hall for the entire school. I made a point of not mentioning my son’s name, but afterward he said he’d felt exactly as I had—proud and embarrassed.

Now, as I stepped forward to receive my diploma from Mr. Chase, I thought of Dad’s triumph. How I wished he could have been there to hear the applause—this time for me.

At Chiq’s insistence, I’d gotten myself a summer job in Sun Valley as a member of the resort crew, building ski trails and cleaning up Baldy Mountain for the coming ski season. Between leaving Eaglebrook and flying out to Idaho, I had a week in the city, staying with Ma and Ave at Eighty-first Street. The first thing I did was call up Holly.

“How about An American in Paris at the Music Hall?”

“I’d love to.”

After the lights went up, we danced out of the Music Hall and straight down Fifty-first Street to Toots Shor’s. Toots threw me a sharp look when I introduced him to Holly. There was no problem ordering a beer. After dinner, no check. The only bumpy moment came when Toots sat down and Holly said, “Isn’t it great that Peter’s going to Yale next year?”

Toots’s eyes bulged at me. Then he bellowed, “Sure is!”

Holly’s place was in Greenwich Village, a walk-up on Sheridan Square. As we climbed the stoop, she took my hand.

“Would you like to come up for a drink?”

“I’d love to.”

She turned the key. “I’m going to do you a big favor,” she whispered.

It was easy, exciting, and over in a flash. Afterward, I examined myself in the bathroom mirror to see if I looked bigger. When I came out, Holly had on her bathrobe.

“It was wonderful,” she said, “but maybe you’d better go.”

I hesitated at the door.

“Have a great year at Hotchkiss,” she whispered as she kissed me good night.

Hotchkiss, in the northwest corner of Connecticut’s Litchfield County, is a magnificent place: acres of white-trimmed brick in the foothills of the Berkshires, with Alpine views of lakes and farms and valleys. Although it’s miles from the nearest town of any size, it didn’t feel isolated. The school’s atmosphere of learning was as open as the vistas. Everything was available to us: the forest trails, the library, the rolling golf course; most of all, teachers who loved to teach. For me, the brightest lights were Albert Sly, the school organist; Malcolm Willis, the music teacher who lured me back to the piano; and Dick Gurney, the English teacher, fly fisherman, and baseball coach, who gave me permission to write my English exams in verse. Fortunately, they’ve not been saved.

Before Hotchkiss, I’d learned about the world by being physical with it. At Hotchkiss I discovered another way: listening. My first serious musical education began at the morning chapel services, with the organ music of Bach and Schütz played by Al Sly. A shy, reserved, balding man with black-rimmed glasses and unnaturally white skin that reddened when he got excited, Al would invite me, Mait, and other music lovers into his rooms to listen to recordings of Bach’s St. John and St. Matthew passions and the B-minor mass, which he thought was the greatest piece of music ever written. I thought so, too, and I still do. Al’s rooms were simply furnished, but the world they opened up to me was indescribably rich. Listening to Bach, I felt a great ordering of things. Everything I had been straining to understand about music suddenly fit together: the harmonies, the bass lines, the rhythms—all the confusions were resolved.

At Hotchkiss I started practicing piano seriously, progressing from the dreaded “Spinning Song” to the Mozart sonatas. I joined a Dixieland band called The Syncopators. There were a half dozen of us, including Dave Ross, who later became a fine poet, on trumpet, and Roswell Rudd, who became a first-class trombonist. Mait dabbled at the piano (more boogie-woogie than anything else), and he’d come around and kibitz. We spent hours playing with blues changes. (“Blues in F” was our favorite number.) We’d try duplicating the solos on records by Armstrong and Bix. Since there was no leader, we’d just sit down and play.

I loved the uncompetitive nature of those sessions. To me, they were far more satisfying than being on the baseball and ski teams. Not that I didn’t love those sports, but winning didn’t mean that much to me—just as it’s never bothered me when a fish slips off my line.

The Syncopators provided the music at the rare school dance. On those occasions I discovered something else: I loved playing for people. It wasn’t that I liked being listened to. It just felt great to be giving everybody a good time.

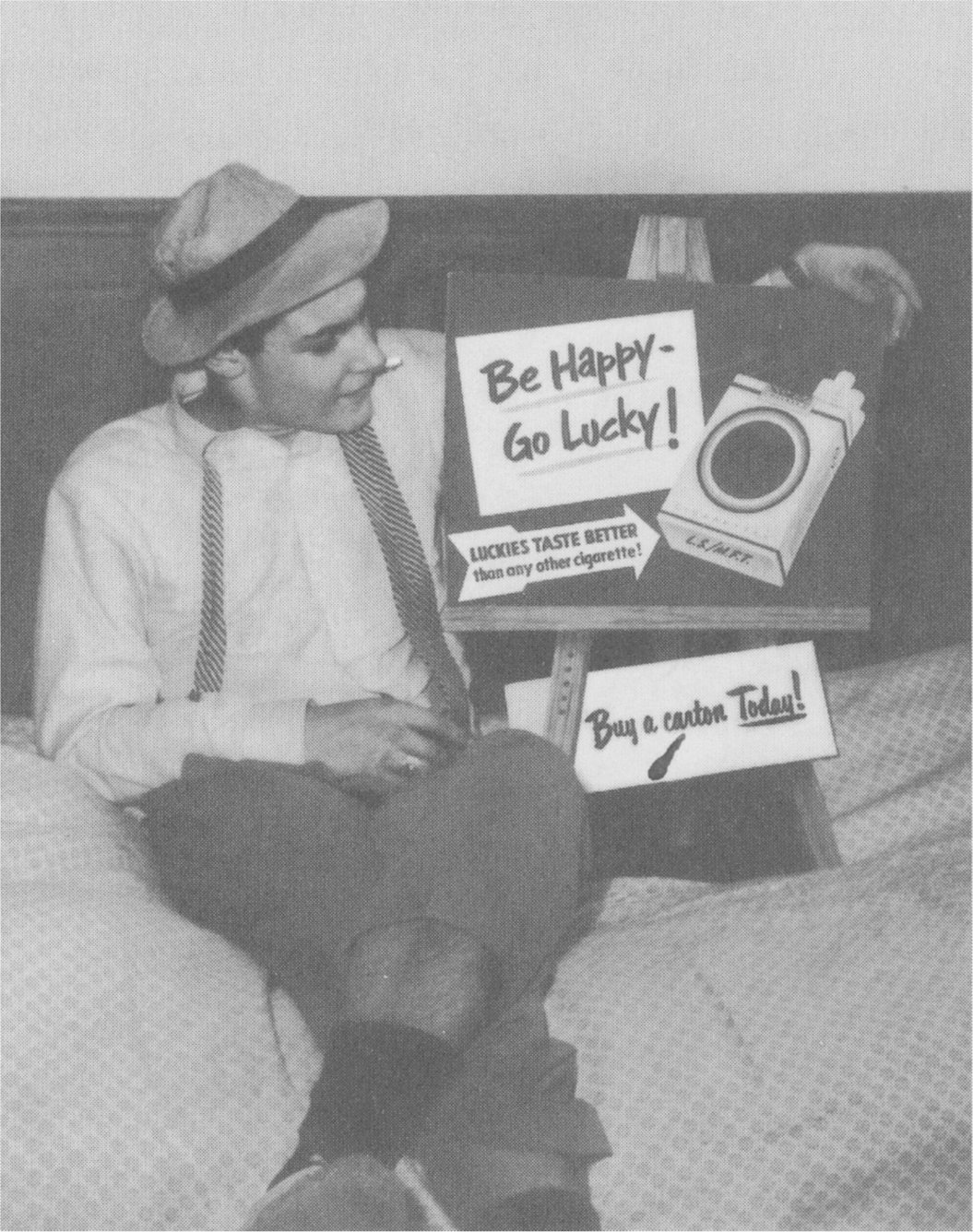

I signed up for the Glee Club, which was directed by Al Sly. Like my father, I wasn’t any good at singing, but the Glee Club was the best ticket to girls. We were allowed only one weekend a semester away from school, and we were desperate for them—or at least the next best thing, which was getting hold of a girl’s picture. Returning with this trophy from Miss Hall’s, Miss Porter’s, or Ethel Walker, you’d Scotch-tape it to your dresser mirror. It meant you had “soul.” Since smoking was forbidden, many of us smoked like chimneys, Luckies and Camels being the coolest brands. We did our lighting up in the woods. One afternoon after a few smokes in a cave by the lake, Mait and I solemnly made small incisions in our right wrists with our penknives. Then we crossed our wrists together and bound them with a handkerchief while the blood flowed. We were brothers for life.

From Al Sly and Malcolm Willis, my piano teacher, I learned that music has meaning, that it isn’t just a bunch of notes put down at random but something made out of thoughts, feelings, and imagination. Mr. Willis, a fine classical pianist (and Sanskrit scholar) with a little goatee, taught by example and analysis. He’d play a sonata by Beethoven and explain that there was a reason why the phrase had to be played just so if it was to connect with the material that had come before and the material that followed.

Hotchkiss awakened a love of classical music that has been one of the deepest constants in my life. Even then, I knew I’d never be a concert pianist—I just didn’t have the chops for it. My fingers are stubby and peasantlike, gardener’s fingers. There was no way I could get through Chopin’s “Revolutionary étude” at top speed. In fact, playing the piano has never come naturally to me. It’s what I do because I’ve done it for so long.

At Hotchkiss there was no anti-intellectual bias. It was as cool to be in music as it was to be a jock. It was even cooler to be obsessed with a weird poet or an obscure mathematician. Dick Gurney made the poetry of Byron, Shelley, Keats, and Coleridge so real—so personal—that we all wanted to read it. Another English teacher, Charlie Garside, once got so carried away with explaining a particularly beautiful line of Milton’s that he leapt out the second-story window to make his point. It was at Hotchkiss that one of my best pals, Ned Bradley, discovered the beauties of Horace and Lucretius, which led him to become a classics professor at Dartmouth. It was cool to read—to be seen immersed in Hermann Hesse’s Steppenwolf or the writings of C. S. Lewis or Arrowsmith by the other Lewis.

In my room at Hotchkiss. Since smoking was forbidden, we smoked like stoves.

Another teacher who meant a great deal to me was Robert Hawkins, who taught grammar. “The Hawk” was a friend of Lakeville’s most illustrious resident, the legendary Bach harpsichordist Wanda Landowska. One day I found myself, along with three or four other musical types, invited to tea at Madame Landowska’s. She lived on a shady knoll in a big, dark frame house that might have been transplanted from her native Poland. Following the Hawk into her cavernous, wood-paneled living room, I had a feeling not unlike the one I had when I’d first encountered Joe DiMaggio.

Madame Landowska was a tiny woman with enormous black eyes and an enormous nose. She was dressed all in black: a fearsome crow. We nibbled hard cookies on a worn old sofa in a room filled with pianos and harpsichords of strange shapes, the walls lined with photographs of the lady with bearded eminences from what seemed to be another century. After we were settled and hushed, she seated herself at one of the instruments and tore into a Bach prelude and fugue with electrifying intensity.

I’ve often wondered what accounts for the power you feel around great artists. It’s a feeling I would later experience with Fred Astaire, Arthur Rubinstein, and Lester Young—maybe a couple of others. At Hotchkiss, I became a terrible snob about artists. Mait and I agreed that they were at the top of humanity’s pecking order. All others were “apes.”

In the postwar fifties, it was assumed that adventure, freedom, romance, the world, were all there on the other side of the Atlantic. Spending a summer in England, France, or Italy before college was mandatory. I had my first European adventure between my junior and senior years at Hotchkiss, when I signed on for a bike tour in France.

There were about a dozen of us, all under the wing of a master and his wife from St. Mark’s School. Both of them, as I think back on it, were remarkably cool. One day, somewhere in the south of France, four of us decided to split off from the group. The only thing our leader said was “Fine, but you’d better be in Paris on such and such a day.”

One of the renegades was a kid named Johnny Loudon, who looked so much like me that we were often taken for twins. After we’d been on the road a couple of days, Johnny and I got sick of cycling and decided to peel off from the other two. We hopped a train and ended up in Saint-Tropez. In those days, before it was discovered by Brigitte Bardot, Saint Trop was the prettiest fishing village in France. Black American jazz musicians had just begun to come there. It was cheap and beautiful, and they were respected and admired by the French. “There is no color line here,” one of them told us. “These cats are really cool.” From there, a train took us to Nice, then to Geneva, so we could see whether the castle of Chillon lived up to Byron’s description of it. It did.

I wanted to check out the music school in Lausanne, so we cycled there. We were coming into town just after dark when we spotted a beautiful stretch of grass and a sign we thought was French for “Camping.” We peed in the bushes. We unrolled our sleeping bags and stretched out on the grass. We went blissfully to sleep. In the morning, we were awakened by a sound I’d never heard before—the twittering of thirty nuns. We had just spent the night on the front lawn of their convent.

They took us in, clothed us, fed us, and washed our clothes. One of the sisters was extremely cute, and though she wouldn’t let me near her, the memory of her lasted well into my senior year—a siren whose image I could conjure up whenever I felt the call of Europe.

A few months after my father died, Chiq had sold our house on Shelter Rock Road to Leland Hayward, the agent and theatrical producer (and father of my second wife, Brooke). For the next couple of years, my home had been the two-bedroom apartment Chiq had taken in the Hotel Carlyle on Madison Avenue. Not that I was often there. Whenever I showed up, Chiq seemed delighted to see me. But our bond was tenuous. She was rebuilding her own life, and apart from the several summers we spent together in Sun Valley, we began seeing less and less of each other.

It was in Sun Valley that she met her new husband, a nice, quiet outdoorsman named Morgan Heap, who worked for the Sun Valley Corporation. Morgan knew horses extremely well, and they seemed to respond instinctively to him. It wasn’t like being with Ave, skilled as he was with horses. Ave’s horses had always seemed nervous around him, as though they knew he was about to discipline them or push them to their fullest on the polo field. Around Morgan, horses were calm. They behaved as if he were one of them.

Morgan was also a great shot. Later that summer, we rode out into the high sagebrush, where he taught me how to shoot dove. He walked with the slight stiffness of someone who has been in the saddle much of his life, and I never saw him miss a bird. When we said good-bye, he gave me a magnificent pair of cowboy boots. I wore them at Hotchkiss that fall and got hooted at. At Hotchkiss, moccasins or white bucks with their hideous pink soles were the shoes of social acceptability. The boots went into the closet, never to be worn except when I was on my own.

The following summer, Chiq and I had gone out to Sun Valley again. I was very glad to see Morgan, and so was Chiq. Morgan blushed whenever I caught them together, and I wasn’t surprised when they announced they were getting married. I’d hoped Chiq would move to Sun Valley so I could come out to ride and shoot with Morgan and ski for free on the mountain. But Chiq had insisted on living back East. They bought a beautiful historic farm in Frederick, Maryland—Chiq thinking, I suppose, that it would be rural enough for Morgan and close enough to New York for her. But Morgan didn’t much take to the Kool-Aid-colored linen pants and blue blazers at the local club. And he didn’t know what to do with himself in New York. For exercise he’d walk around the entire circumference of Manhattan, every day. I had a feeling their marriage wouldn’t last very long, and it didn’t.

Though Chiq’s doors were open to me, I preferred spending weekends and vacations with Harry Whitney and his wife, Axie, at their crazy old house in Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia. Axie was an earthy woman, a sculptress, with spectacular, Cleopatra-like, wide-apart eyes. She had an unlimited ability to put up with Harry’s shenanigans, which were more pronounced than ever: his insane car racing, his tearing off on archaeological digs to the Middle East or a remote Pacific island, his solitary excursions into the Adirondacks to stalk deer, his passion for opera, his motorcycles. She even followed him around on her own motorcycle, which I thought was extremely cool. Ma adored her but thought she was a bit nuts to put up with Harry the way she did.

Everything was a bit nuts around Harry. The neighborhood was classy, but what you were likely to see as you approached the Whitney house was a motorcycle in a hundred pieces on the front lawn, or the eggplant-colored Allard getting a touch-up in the driveway, or a couple of Harry’s buddies working on their Formula Two racing cars out by the garage. Inside, Harry might be having a discussion in the living room about the possibilities of Bucky Fuller’s geodesic dome for low-income housing with his friend the visionary landscape architect Ian McHarg, while The Magic Flute blasted at full volume through the hi-fi. I was intoxicated.

In the meantime, I’d found another home—the Edeys’ estate in Brookville, Long Island. During our junior year at Hotchkiss, Mait asked his mother if she and Mr. Edey could adopt me. A formal adoption wasn’t in the cards. But Mrs. Edey went to my guardians, Donald Stralem and Chiquita, and asked if it would be all right for me to regard the Edey household as my “home away from school.” They agreed. And so I moved in with the Edeys—into the big room above the garage where Mait and I could fantasize all night about girls, the poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay, and jazz.

Maitland Edey, Sr., was a top editor at Life magazine, a good-looking man, charming and outgoing, one of those adults who makes an effort with kids. He was a fine athlete and competitor, terrific at tennis and bridge, and an avid sailor. When I once asked if I could fish from his boat, he looked at me in mock horror and said, “Peter, the only fish that will ever touch my deck will be an errant flying fish.”

I thought Mait even luckier with his mother. Helen Edey was a civilized, hyper-intelligent woman who had become a psychiatrist after giving birth to four children. She was the first adult I’d ever met who seemed genuinely curious about who I was and how I would turn out. One evening I got brave enough to say I was worried that my birth might have caused my mother’s death. Helen stopped what she was doing and looked me straight in the eye. “Why do you think so?” she asked.

I told her that in the scrapbooks from my childhood, my nurses had obliterated all references to my mother’s death. This brought out the shrink in Helen: “Have you ever talked to anyone about this?”

I hadn’t.

“Well,” she suggested, “it might not be a bad idea sometime. In the meantime, remember that many people use past events like this as excuses for their eccentric behavior. You don’t seem to be consciously bothered by it, but the more you try to be honest about your deepest feelings about your mother’s death and the more you come to grips with them, the saner and healthier you’ll be.”

Nobody had ever talked this way to me before. The kind people who had raised me had been determined to put a bright face on anything that might disturb me, or pretend it hadn’t happened at all. It was as though I were to be kept in a state of permanent innocence, forever in that oxygen tent. Helen Edey made me realize that although I wasn’t to blame for my mother’s death, I was responsible for the feelings it stirred up in me, and they were better faced than hidden.

What I respected about her most was her sense of standards. She had thought carefully about right and wrong and had passed those thoughts along to Mait. Until now, I had seen anger in adults as a reaction, a sudden, mysterious reflex. When Helen disapproved of something, you felt her reaction as the expression of a deep morality, one she’d been cultivating for years.

Helen didn’t give a damn about style. Unlike Ma or Chiq, who cared enormously about what things—and they—looked like, Helen had no interest in decor or fashion. To her, what mattered were things of the mind and the emotions. I was used to adults gushing over me because of who my father was. But Helen didn’t seem the least bit impressed by Eddy Duchin, and I liked her all the more for it.

What I liked best about staying at the Edeys’ was the feeling of being part of a “normal” family—one that was bound together by nature. Now I see that things were a little more complicated.

After Mait, the eldest Edey, came his brother, Kelly, one and a half years younger, a sensitive, deeply self-involved, perhaps lonely child. Early on, he showed a great interest in clocks, and today his collection of antique timepieces is one of the finest in the world and his horological opinions are sought out by museums. Their sister, Beatrice, seemed to us to be a conventional girl who had her heart set on doing good. Marion, the youngest, marched to her own, different drummer. She spoke of “hearing voices” and grew up to become a well-known environmentalist.

I liked all of them for their individuality and the freedom with which they spoke up at the dinner table. I had never been in a family where what had happened during the day was subject for discussion in the evening. Mait and I had read that Edna St. Vincent Millay had called her parents Mumbles and Daddles, and we conferred those names on his parents.

As inseparable as Mait and I were, there were pronounced differences between us. One Thanksgiving, Kate Roosevelt Whitney, a close friend from Manhasset, invited us down to Greenwood, her stepfather John Hay Whitney’s plantation in Thomasville, Georgia. It was a huge, wonderful place that seemed to be used strictly for shooting quail, dove, and wild turkey. One of the other guests was John “Shipwreck” Kelly, the famous all-American football player and a great crony of Jock’s.

A towering, stormy figure, he suddenly interrupted everyone at dinner to ask if Mait and I were joining the quail shoot the next morning.

“You bet!” I said. “Can’t wait!”

Shipwreck cast his gimlet gaze on Mait, who was looking down at his plate. “How about it, kid? You a good wing shot?”

“Well, sir,” Mait replied, “I don’t think I’m going to go out and shoot because I don’t believe in it. I think it’s wrong.”

There was dead silence. The eyes of the servants, standing with the silver trays, went heavenward.

“What are you?” Shipwreck bellowed. “Some kind of goddamn nature boy?”

Mait stared at him.

A woman jumped in. “I think he’s very courageous—”

She was drowned out by Shipwreck. “Well, that’s what I’m going to call you…Nature Boy!”

Jock Whitney, the nicest of men, threw a disapproving look at his buddy. Turning to Mait, he said, “Don’t let it bother you, son. You certainly don’t have to shoot with us. But do come and ride.”

Mait smiled. The moment passed. But from then on, whenever I ran into Shipwreck, he’d greet me with “How’s your friend, Nature Boy?”

“Just fine,” I’d say, thinking about what guts my friend Mait had.