11

11

PARIS

Number 13 Rue Monsieur is an eighteenth-century apartment complex, a hôtel particulier, on a quiet residential street on the Left Bank. To get to Ginny and Brose Chambers’ house, you first had to go through a set of massive, studded wooden doors, then past the concierge’s apartment, then across a cobblestone courtyard big enough for several coach-and-fours. Then you opened another set of ancient doors to discover an entire house in the Norman style, with a surrounding garden. Paradise.

Ginny had bought the place from Cole Porter just after the war, when Brose was in Paris working with Ave as a lawyer on the Marshall Plan. Cole had transformed an eighteenth-century house into a country manor, adding timbers and stucco to the façade and planting an astonishing “secret garden” of flowering shrubs and trees around the sizable lawn in the back. Once you arrived in the inner sanctum, the only reminder that you were in a city was the occasional two-note police siren.

Ginny had furnished the former ballroom on the ground floor with her collection of modern paintings. Some of them were hung; others stood on easels; others were strewn about the floor. She called it “the studio” even though nobody ever painted in it. It was reserved for the works of artists who were her friends. Upstairs, she’d kept the eighteenth-century parquet floors and boiserie and furnished the procession of sitting rooms, bedrooms, and dining room with an eclectic assortment of thoroughly lived-in antiques. Ginny and Brose had two giant, precocious poodles, who were given full rein of the house. They were so attuned to their mistress’s comings and goings that the moment they heard her car turning into the Rue Monsieur, they dashed upstairs and sat in the window, whimpering with excitement as she made her entrance in the courtyard below.

Everybody who came to Ginny’s for one of her lunches or dinners wanted to move in forever, especially into one of the bedrooms at the top of a spiral staircase in the tower overlooking the garden. Ginny’s kitchen, supervised by Leon, the butler, turned out some of the best food in Paris. Her wine cellar was superb. Her Bösendorfer grand piano in the library was concert quality. Ginny was what the French call a maîtresse de maison. She ran a house better than anybody.

Like her best friend, Marie Harriman, Ginny was an anomaly in a mostly Wasp world. She came from a cultivated family of Sephardic Jews in Virginia, the Fargeons, the British branch of which was prominent in the arts. Her English cousin Herbert Fargeon was a famous theatrical producer; his daughter, Eleanor, a well-known popular novelist. Ginny’s father had been an insurance executive who specialized in protecting many of the great American art collections, which explained her considerable knowledge of paintings.

Ginny could never have been a beauty. She was slightly hunchbacked and had gray, thinning hair. In old age she wore a wig. Her husband affectionately called her Monk, a diminutive of “little monkey,” in reference to her funny, animated face. Ginny’s voice was even huskier than Ma’s from years of booze and cigarettes. Like Ma, too, she suffered from progressively failing eyesight. A dozen years later, after she sold the Paris house and moved to New York, she went virtually blind. But this didn’t prevent her from charging out of her apartment in the Mayfair Hotel and running into the street to hail a cab.

She was the epitome of understated chic, even when she appeared in the morning in her pink quilted dressing gown, nursing a hangover. There was nothing veiled about Ginny, who had the sweetest smile in the world. She was the most inviting woman I’ve ever met.

Her tragedy was that, despite her great maternal instincts, she never had a child of her own. To fill the void, her Paris house became a way station for the children of her American friends, whom she Auntie Mamed through their adolescent rawness and first love affairs. Ginny had offered to bring me up after my mother died, and it was only natural that the project of civilizing me became a top priority when I arrived at Rue Monsieur in August 1956. I had stayed there before but never for more than a week or ten days. This time, Ginny had an entire school year to work on me. She approved of my desire to study music and French history, but she warned me that the daybed in her studio would be available only for a couple of weeks. It was important, she explained, that I develop “self-reliance.” I nodded dimly.

Ginny and Brose Chambers at the Stork Club during the war. They bought Cole Porter’s place in Paris when Brose was working with Ave on the Marshall Plan, and it was always filled with the most interesting people in town. Ginny was my godmother, and I was welcome there anytime.

The Communists had splashed “U.S. Go Home” all over Paris. But to most Parisians, Americans were more than welcome. The older French respected us as “liberators,” although it didn’t take long for us to realize that while they boasted about their role in la Résistance, most of them had been totally supine under the Nazi boot. The younger French were crazy about American movies, American jazz, American writers—especially Faulkner, Hemingway, and Fitzgerald. What everyone liked best about us was our money, of which we seemed to have a great deal more than they. For Americans in the fifties, Paris was the way it had been for Hemingway and Fitzgerald in the twenties—a movable feast.

Now I was really free. Until then, I’d moved in a world governed, monitored, and manipulated by adults who expected me to measure up to some set of standards that were always implied but never exactly spelled out. I’d been eager to fit in, to be liked, not to displease. My only rebellions had been minor transgressions of the adult code. When I’d been caught, the usual reaction had been, “You’ve disappointed us.” From the moment I arrived in Paris, I felt responsible to nobody but myself.

Paris was the first city I claimed as my own. Thanks to Zellie, I spoke the language fluently, which immediately made me accepted by the French. For weeks, I walked the streets as if in a dream. I loved the way everything had its place in the grand scheme of things: the bird market, the flower market, the fish market, the whore market.

Paris sounded wonderful. It might be a dog barking, or someone practicing Chopin behind an open window, or people calling out to one another, or just a howl of wind. Each sound had its own identity, the way a Miles Davis riff suddenly breaks out, then stops, only to haunt the silence. Very soon I was able to distinguish among the variety of French accents: the aristocratic, the working-class, the provincial, the colonial.

One destination became an obsession: the Musée de Cluny in the Latin Quarter. There, in the ground-floor gallery, I would sit gazing at the six millefleur unicorn tapestries from the Middle Ages, each depicting one of the senses (the sixth being freedom of choice). I had been enchanted by unicorns since I was about seven or eight and found a big art book in Ma and Ave’s cottage. Nancy Whitney had come in and told me that the strange animal in the pictures, standing alone in a leafy bower, was “not a real animal—it’s mythological.” The sound of that word mythological made the creature even more magical, and for a long time I’d refused to believe that unicorns weren’t real. I was sure I’d spot one in the woods at Arden and, even later, in the woods around Eaglebrook.

At the Cluny I was drawn particularly to two of the tapestries, the ones depicting touch and sight. In the former, a beautiful princess gently grasps the creature’s horn. It was an act I found unbearably erotic. In the second tapestry, she holds a mirror in which the animal can look at himself. I was haunted by the princess’s vulnerability and bravery. What I liked about her animal/lover was its innocence and trust.

From the museum I would wander over to the Luxembourg Gardens to see “the Birdman.” He was a clochard, one of the raggedy old men of the Paris streets, and he’d be sitting on a bench, covered with live birds. One day I bought a bag of corn, seated myself on a bench opposite, and sprinkled the kernels over my hair and lap. In a flash, the birds were all over me, gobbling up the corn. Once it was gone, they zoomed back to their perches on the Birdman, from where they eyed me suspiciously.

At 13 Rue Monsieur, you might see Simone de Beauvoir schmoozing with Audrey Hepburn, James and Gloria Jones with Raymond Aron, Jacques Barzun with John J. McCloy, Anita Loos with Pauline de Rothschild. Ginny made no distinctions between young and old, rich and poor, famous and unknown. All she expected of me was that I show up reasonably clean, sound reasonably intelligent (in French), and help Leon with the drinks.

Occasionally she’d fix me up with attractive daughters of Brose’s French business friends. Shortly after I arrived, I was introduced to Claudine, a gorgeous eighteen-year-old blonde, who invited me to a debutante party in the Bois de Boulogne. Lacking a tuxedo, I tried on Brose’s evening clothes. They fit fine, but our feet were different sizes, and I didn’t have a pair of black shoes. Ginny came up with the idea of blackening my brown oxfords with shoe polish. After several coats had been thickly applied, I left to pick up Claudine in my Deux-Chevaux.

She looked fantastic in a white, strapless ball gown as we walked into a million twinkling lights, masses of flowers, a battalion of waiters bearing Dom Pérignon, and a spread of food, all sculpted and glacéed, as only the French can do it. We danced and danced, and though I received many scornful glances from her snooty French friends, I was sure she only had eyes for me.

Toward the end of the evening, I was cut in on by a dark young man who looked like Louis Jourdan. As I reluctantly retreated, I glanced back to give Claudine a debonair wink. To my horror, I saw a wide black band encircling the hem of her gown. Her partner followed my downward gaze.

“Qu’est-ce que c’est ça?”

Claudine looked down. “Je ne sais pas!”

Her hand went down to the black, then up to her nose. Her eyes found mine. I pointed to my shoes and did my best Fernandel imitation. She threw back her head and laughed.

Mait was staying nearby, and almost every night we’d hit the clubs. There was a wonderful array of them on the Left Bank, where you could hear jazz in every style, played by top American musicians and a lot of terrific French players. Among the Americans were Sidney Bechet, Lester Young, Bud Powell, Chet Baker, David Amram, Allen Eager, Billy Byears, Kenny Clarke, and Don Byas. The French stars included Martial Solal, Stéphane Grappelli, and Claude Luter. One day Miles Davis blew into Le Vieux Colombier off the Boulevard Saint-Michel, and Mait and I were there for every set, five nights running.

Our evenings would end around four in the morning with long “existential” walks along the Seine. One night we met a French student who invited us to his pad. There we had our first hit of marijuana. It felt great, but later, as we made our way home on rubbery legs, we were sure we’d taken the first step to heroin. Hard drugs were cheap and plentiful in those days, and others in our crowd were already making the most of them.

I ran into an old friend from New York, Harry Phipps, whose father was Ogden Phipps of the immense steel fortune. Despite his blond, perfect-preppy good looks, Harry had always been the sweetest, kindest, yet most mysterious member of the group of Long Island friends who were a few years older than I. In the hard-playing, athletic North Shore crowd, Harry had stood out because of his artistic inclinations, which included a great interest in jazz. One night after Harry and I closed the clubs, I found myself back in his apartment, below the Tour d’Argent restaurant. While I made myself a drink, he took out a little envelope, poured some white powder on the table, and snorted it up his nose with a drinking straw.

“What’s that?”

“Heroin. Want some?”

“No thanks.”

While I watched, he shrugged and snorted some more. Then he put his head back against a pillow and went quietly to sleep, peaceful as a baby.

I split, pursued by demons.

From then on, I saw a great deal of Harry and his heroin addiction, even joining him in London for a wedding where we were introduced to an attractive couple from Washington, Sen. John F. Kennedy and his beautiful wife, Jackie.

Harry was the first person whose survival I’d ever really worried about and whom I thought I could save. On the occasions when he was clearheaded, I’d tell him that heroin was ruining him. His response was always the same: Of course he was going to stop—it was just something he was “doing for now.” The next time I saw him, he’d look as though he were about to fall asleep standing up. He was still on the junk.

I had grown fond of marijuana, but I never tried heroin. I knew I’d like it. It’s the same thing that has kept me from ever snorting cocaine—something my children refuse to believe.

Six or seven years later, back in New York, Harry came to the end of the road—one that had undoubtedly begun when his self-absorbed parents were divorced and he was left, like so many privileged Wasp kids, to be raised largely by society. I had been at lunch with Harry’s wife, Diana, a brilliant, Czech-born woman who shared his artistic interests but not his drive to self-destruct. As I dropped her off at her apartment on Central Park West, the doorman took me aside. “Mr. Duchin,” he said, “Mr. Phipps has been found dead.”

Diana came over and said, “What’s wrong?”

When I told her that Harry had died, she let out the most awful shriek and fell to the sidewalk. I caught her and half-carried her to the elevator. Upstairs, we learned that Harry, age thirty-one, had OD’d that morning in a Times Square hotel room.

I thought I had just about charmed Ginny into letting me stay the whole year on the Rue Monsieur when I went too far. Kate Roosevelt, Betsey Whitney’s daughter by her first marriage, to James Roosevelt, the president’s oldest son, had been a close friend since my days at Arden. In Manhasset, we had often played together just down the road on the Whitney estate, Greentree, which was so big that we both regularly got lost. I was delighted when Kate arrived at Ginny’s to stay for several weeks in one of the tower bedrooms, and every night—or early morning—I would go up to her room and tell her about my nocturnal adventures. One night when I was perched at the foot of Kate’s bed wearing nothing but my bathrobe and holding a cigar and a tumbler of Scotch, Ginny walked in. “Good God!” she said. “I think you’ve been here long enough, young man!”

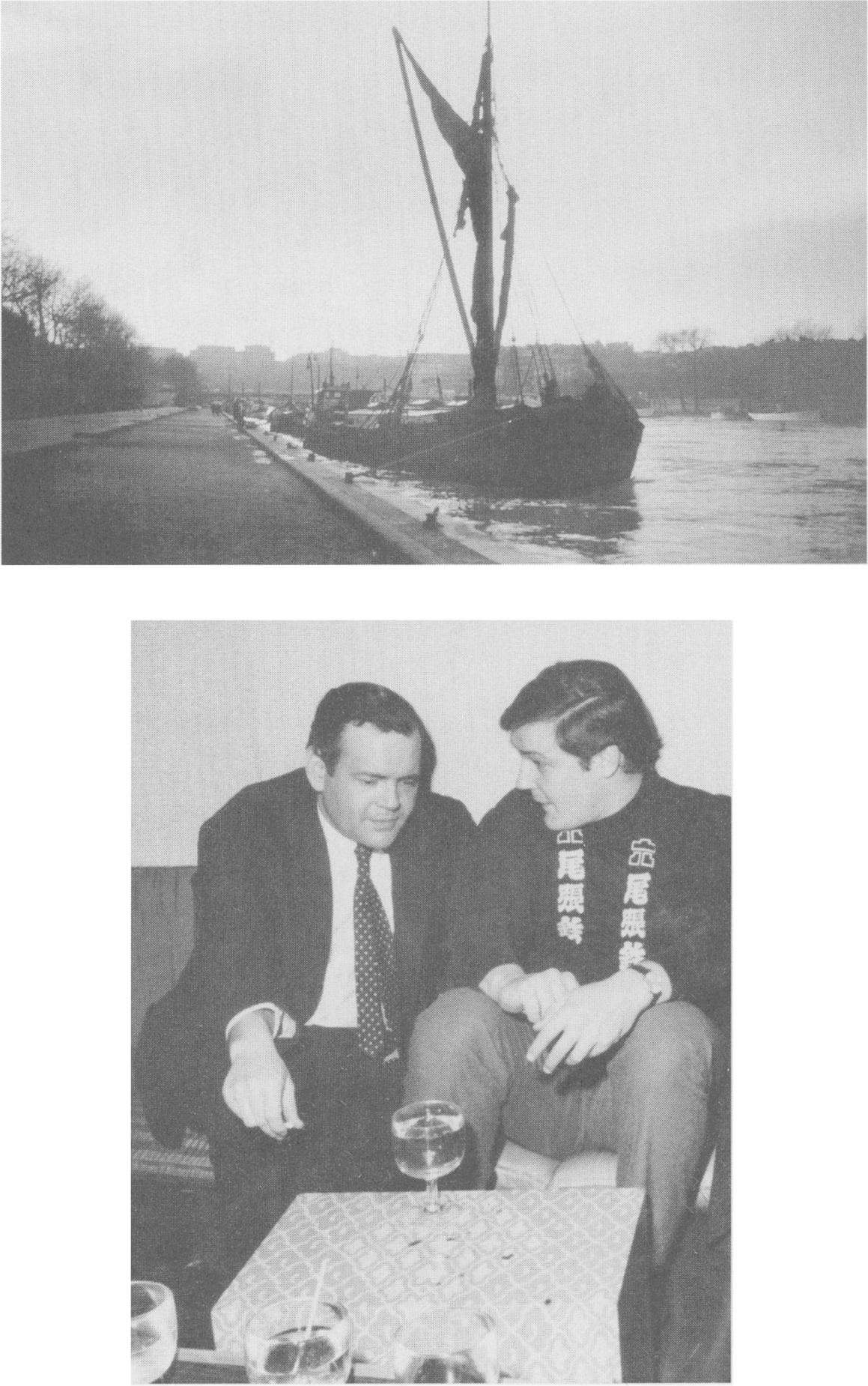

I found the barge through a newspaper ad. Built in the nineteenth century to haul grain up and down the Thames, it still had its original deck and a mast with rotting tanbark sails. At some point, it had been converted to a houseboat. Somebody had sailed it across the English Channel and down the Seine, where it was now docked on the Right Bank, between the Pont de l’Alma and the Pont des Invalides.

I ran over to see it and fell in love. For light, it had a good supply of Coleman lanterns; for heat, a potbellied woodstove. The barge’s plumbing consisted of hoses that drained into the Seine. Running water came from a hose attached to a spigot on the quai. In what was formerly the hold were three bedrooms, a small galley, and a pine-paneled living area with cheap furniture, including an old upright piano. George Plimpton later described the main cabin as “dark and finely odiferous.” I thought it was the most romantic place in the world.

The asking price was $6,000. I got it for $5,400. Since I didn’t have the money myself, I got Mait to pony up two-thirds. I persuaded another friend, Mark Rudkin, whose family owned Pepperidge Farm bakery products, to put in the other third until I could weasel the money out of Donald Stralem and Chiquita, the administrators of my modest trust fund. Ginny came over for a look and pronounced it “very amusing.”

Then, unexpectedly, the barge was mine. Mark left to study landscape design outside Paris. Mait, who had been pining for the Swedish girl, left Paris to court her in Göteborg. I needed a roommate to help with the expenses.

It was George Plimpton, editor of The Paris Review, who suggested I meet Robert Silvers, the magazine’s new Paris editor. I went around to where Bob was staying on the Île Saint-Louis and was bowled over. At twenty-six, he looked a bit like the young Orson Welles, and he was clearly another wunderkind.

Bob, who has been editor of The New York Review of Books since helping to found it in the mid-sixties, had grown up on a chicken farm in Long Island—something you’d never suspect from his immensely cultivated manner. At age fifteen, he’d gone to the University of Chicago. At seventeen, he’d been accepted into Yale Law School. He’d dropped out to be a reporter and at nineteen had become press secretary to Chester Bowles, the governor of Connecticut. He was studying at Columbia when he was drafted into the Army. After serving in SHAPE, the Allied command headquarters in Paris, he had attended the Sorbonne and the école des Sciences Politiques on the GI Bill.

He’d joined The Paris Review as an editor in 1954, and when George Plimpton went back to America in 1955 to run the magazine from New York, he’d asked Bob to take over the Paris office. Bob’s main concern at the Review was to find European writers to publish in translation, as well as artists who would contribute portfolios of drawings. He came around to look at the barge and liked what he saw. And I suddenly found myself at the center of one of the most interesting scenes in Paris.

The Paris Review was already three years old. The brainchild of two American expatriates, Peter Matthiessen, the novelist and naturalist, and the eccentric publisher and novelist Harold L. (Doc) Humes, the magazine had become a mecca for well-connected young Americans, mostly fresh out of Harvard, who were eager to make their literary marks. One of their gurus was the novelist Irwin Shaw, who knew everybody who was anybody in a Europe that was bordered on the east by Klosters, on the north by Deauville, on the west by Pamplona, and on the south by Saint-Tropez. I met Shaw at one of Ginny’s more memorable dinner parties. I had just read his war novel, The Young Lions, and when I heard who the tough-looking, animated guy with the permanent five-o’clock shadow was, I stood there tongue-tied. He was a geyser of names, all glamorous, famous, or wealthy: the Duke of Windsor, Hemingway, James Jones, Darryl Zanuck, Gary Cooper, Aly Khan. Listening to him with great interest was a good-looking, very fit man, the screenwriter Peter Viertel, who had walked in with another astonishing figure—his wife, Deborah Kerr. It was hard to believe that the prim lady sitting quietly in the corner was the same woman I’d last seen in From Here to Eternity, rolling around the sands of Waikiki with Burt Lancaster.

My roommate on a barge in Paris was Bob Silvers, who edited The Paris Review, then in its third year. Thus I was surrounded by well-connected young American writers having a great time being bohemians.

I was fascinated by two Mutt and Jeff characters who were also orbiting Shaw. Both wore business suits and had identical round, black-rimmed glasses. The Mutt figure was a strange-looking little man with a shiny pink head as bald as a cue ball and batlike ears. He was introduced to me as Irving Lazar, though everyone called him Swifty. He seemed to be some sort of agent. The Jeff figure was Harry Kurnitz, a playwright and novelist.

In time, I developed a passing friendship with Shaw, who would sometimes drop in on the barge to chat with Bob. He was always curious about and supportive of what the Review was publishing, and for the magazine’s twenty-fifth anniversary issue he wrote an assessment of how my generation of would-be Hemingways differed from his. The latter, who were products of the Depression, had been

ferociously competitive, honest in their opinions of their friends’ work to the point of snarling hostility, fanatically and openly ambitious, poor, and out of grim necessity ready to do any kind of writing that promised to support them and their families….

In contrast, the literary hopefuls of the [Paris Review] contingent spoke in the casual tones of the good schools and could be found, surrounded by flocks of pretty and nobly acquiescent girls, in chic places like Lipp’s on the Boulevard St. Germain or on the roads to Deauville or Biarritz for month-long holidays. They were mild-mannered, beautifully polite, recoiled from the appearance of seeming ambitious and were ready at all times to drop whatever they were almost secretly composing to play tennis (usually very well), drive down to Spain for a bullfight, fly to Rome for a wedding or sit around most of the night drinking. As far as I could see, none of them had a job and although they all lived frugally in cheap rooms they gave the impression that they were going through a period of Gallic slumming for the fun of it. One guessed that there were wealthy and benevolent parents on the other side of the Atlantic.

All true. We weren’t really living the Bohemian life—we were playing it. George Plimpton has remarked that “we were all very good at leading two lives—the life of the incredibly inexpensive hotel room, where you could live for fifteen dollars a week, and the lavish drawing room. As long as you had a dinner jacket in the armoire, you’d be invited to the most fabulous houses of unbelievable wealth.”

I should add that when George dropped over to Paris, he’d spend a few nights with Bob and me on the barge, sleeping on an army cot with his feet sticking out. In the morning, he’d amble up the street to the Plaza-Athénée, where he’d write letters home on the hotel’s embossed stationery.

No one could accuse Bob Silvers of being anything other than serious, however. He seemed to know more about more subjects than anybody I’d ever met, yet he was the least intimidating of intellectuals, never too busy to share what he knew, even with a lout like me. You could ask him about anything—the difference between the philosophies of Wittgenstein and Whitehead or the complexities of French politics in 1925—and he’d come back with a concise answer. Sharing the barge with Bob was like living with a cozy encyclopedia.

Another mentor was Eddie Morgan, whom I had known since his marriage to Nancy Whitney. They were now divorced, and Eddie had started a car sales and rental business in Paris, dealing mostly with GI’s who were finishing up their military service and wanted a foreign car to take back home. In his mid-thirties, Eddie was an intellectual and stylistic Pied Piper for us all, even for Bob Silvers. He had fought in the war in the Marines, which gave him gravitas. He knew Paris inside out. His mind was amazingly well stocked, particularly in arcane matters of history and politics. Big, dark-haired, aristocratic-looking, and dressed in fashionably threadbare suits, he had the vaguely tragic aura of a man destined for great things and doomed never to realize them.

Eddie was a night owl. The later it got and the more beer he drank, the more eloquently he would discourse on the virtues and shortcomings of Alexander the Great compared with those of Charles de Gaulle. Or the story of the Morgan family, which the way he told it became a mini-history of American business and privileged society since the Civil War. Eddie would hold his tongue until the rest of us were exhausted. As one of my friends, Teddy Van Zuylen, once remarked, “Eddie never really opened his mouth until 3:00 A.M.”

One of the reasons I found Eddie so compelling was that he seemed in the grip of some immense inner turmoil. He would wring his hands so fiercely that they developed calluses on the palms. Eddie projected density. He was a constant reminder that I’d better stop frittering my time away on the pursuit of pleasure.

Because of Bob and Eddie, I was admitted into an impressive group of brains, beauty, and connections. One of Bob’s assistants was Gill Goldsmith, the witty wife of Teddy Goldsmith, the eccentric brother of the financier James Goldsmith, who is now the owner of Ginny’s house on the Rue Monsieur. Teddy, whose parents owned various grand hotels, claimed to be writing the “history of the world.” He once rushed to Gill and exclaimed, “I’ve just finished chapter fourteen!” “Darling, how wonderful!” she said. “You’ve written fourteen chapters?”

“No, idiot!” he screamed. “I’ve started with chapter fourteen.”

Another assistant at the magazine was Elizabeth de Cuevas, daughter of Margaret Rockefeller and the Marquis de Cuevas, who had his own ballet company. Bessie, as everyone called her, was a rather shy beauty, married to an elegant Parisian businessman, Hubert Faure. There was Gaby Van Zuylen, a poetic Radcliffe girl, whose husband, Teddy Van Zuylen, was an enormously rich, half-Belgian, half-Egyptian count who owned a fabulous castle, Le Haar, in Nijmegen, Holland. One of Bob’s first acts as Paris editor had been to move the printing operation to a plant in Holland. Later, when Gaby joined the Review, we were invited to use Teddy’s place for long weekends of visits to the newly built van Gogh museum, strolls in the private forest, and gambling all night.

Closer to Paris was another favorite weekend haunt. Bob, Eddie, and I would fold our bulky American bodies into my tiny, secondhand Citroën Deux-Chevaux for the drive to the château of Lionel and Nolwen Armand de l’Isle in Dreux, near Chartres. This many-turreted edifice was divided into the Light Side and the Dark Side. In the former lived Lionel and Nolwen and their beautiful young daughter and son. There, the routine was completely casual. A bit down at the heels, it was a place where dogs, children, and adults tumbled all over one another. In the Dark Side lived Lionel’s parents. This was a hushed, dim procession of stuffy, cold rooms into which we ventured only for formal holiday dinners. Presiding dourly was Lionel’s father, a once celebrated doctor whose research with rabbits some years earlier had unleashed a plague of mixemetosis that had nearly wiped out Europe’s rabbit population. Boris Karloff would have been perfect casting as Dr. Armand de l’Isle. His wife, Madame de l’Isle, seemed to spend all her time outdoors, wearing a huge shawl and carrying a basket on her arm, slowly picking her way through the mist, searching for nuts or mushrooms.

Adding to the charms of the barge was the proximity of the Crazy Horse Saloon, just up the street. The most popular of the postwar nightclubs, the Crazy Horse featured floor shows that weren’t as extravagant as those at the Folies-Bergère or the Lido, but its girls were considered the most stunning in Paris. To avoid paying the cover charge, I’d park myself at the bar just as the last show was ending. Soon the girls would arrive, some in costume, some not—a United Nations of pulchritude. I played the wide-eyed American student and would-be jazz musician to the hilt. Eventually the girls who hadn’t succeeded in landing bigger fish would settle at my table. They needed a friend as much as I did, with no strings. I felt a great tenderness for them, especially the ones who thought they had to barter their charms for extra cash or a rich husband. All I had to give them was my youth and raging libido. Invariably I’d end the night with one of them, often on the barge, where I’d sit at the piano and doodle at something beautiful and hip by Thelonious Monk or Bud Powell while the girl arranged herself in a pose by Degas.

Another prime hunting ground for girls was the Latin Quarter, which teemed with bright, young, beautiful people of all nationalities, most of whom were tasting freedom for the first time. The pill hadn’t yet arrived, but these were not girls from Miss Porter’s. These girls went all the way.

One night I met an exotic beauty named Nina Dyer. Recently divorced from the German industrialist and art collector Heinrich von Thyssen, she was said to spend a good deal of her settlement on the care and feeding of a black panther, which she kept at her country house in a cage. When she wasn’t throwing the beast large haunches of bloody meat, she liked to parade him around on a chain. We hit it off when I told her how my great-aunt Blanche had kept an ocelot that she would take out for walks on the streets of New York.

“You must meet my panther,” murmured Nina.

I walked her home and went up for a drink. After the butler left us, I joined her on the couch. I was making the first move when I heard the rapid approach of not so tiny feet. Suddenly a large, toothy mouth was inserting itself between our faces and preparing to take half of mine in its jaws.

“Arrêtes, Pushkin!” screamed Nina.

Pushkin, an extremely elegant borzoi, sat down and licked his chops. It wasn’t serious, but his teeth had drawn blood. Nina ran for a towel. While she dabbed at me, Pushkin and I eyed each other.

A week later at Neuilly, I was introduced to Nina’s panther. This time I kept my distance. But as things progressed between Nina and me, the panther grew fond of me. At least he didn’t seem to care when Nina and I got close.

Another encounter with a girl and her pet did not end so well. It began at a dinner given by Bessie de Cuevas, where I was seated next to a fetching young woman, a Rothschild of some sort whom I’ll call Celestine. Over the sorbet we looked deep into each other’s eyes. Later, she agreed to let me walk her home to the Rue du Bac. There we exchanged more deep looks, and she invited me up. “But first,” she added, “we have to take Loulou for a walk. Would you mind?”

Not at all.

Celestine ran upstairs and returned with Loulou, a yapping Yorkshire terrier with a pink ribbon around a topknot. The three of us set off, Loulou in the lead, Celestine and I arm in arm. We hadn’t gone far when Loulou spied another dog and jerked out of her mistress’s grasp. Gallantly I raced after her. With one leap, I landed my left foot on her trailing leash. She stopped, but my right foot didn’t. There was a sickening crunch of tiny backbone. I scooped up Loulou, deposited her in a dustbin, kept running, and didn’t look back.

The next morning I sent Celestine two dozen sunflowers with a note saying I didn’t know how I could feel worse. She didn’t write back, and for weeks I avoided the quartier around the Rue du Bac. As luck would have it, I never saw Celestine again.

I had enrolled in the School of Life but had somehow not found the time to enroll at the Sorbonne. Several weeks past the deadline for registration, I received a rocket from Chiquita, who had gotten a letter from the director of the Junior Year Abroad program—one Monsieur Rideout—which she had enclosed. M. Rideout began: “To say that Peter has been a disappointment to me is making an understatement.”

From there, M. Rideout proceeded to charge me with “acting independently” and an “inability to set [my] sights on a single goal.”

Moreover, M. Rideout was “very much concerned” that I might “continue to be a lone wolf and perhaps a waster of time.” He conceded that I seemed “a young man of considerable intelligence and native ability.” What was wrong was my “frame of mind.” Apparently I was, he wrote, in “rebellion against Yale and everything else that attempts to dictate his life to him.”

All true.

A few days later, I got another rocket, this one from my guardian Donald Stralem in New York. Donald was furious that I had bought the barge without his permission, and he was not happy about sending me the money to pay back my friends. “As far as I can make out,” he wrote, “all you have succeeded in doing is being an utterly foolish juvenile.”

Not quite all true.

There were two musical grandes dames in Paris to whom aspiring American composers beat a path in those days: Mlle. Nadia Boulanger and Mme. Andrée Honegger, widow of the distinguished French composer Arthur Honegger. Madame Boulanger, whose finishing school had accommodated Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson, was too advanced for me. Madame Honegger taught composition “for beginners” at the école Normale de Musique. Having squeezed myself into a couple of courses in French history and literature, I signed up for an audition.

The woman who answered my timid knock was small, gray haired, and severe. She was impressed that I’d been at Yale, the domain of Paul Hindemith, but she cautioned that her approach emphasized dictation—that is, the taking down of complex scores while she played them on the piano.

I nodded with false confidence.

“ça va,” she said.

Madame Honegger’s class, which met twice a week, was—to put it mildly—daunting. There were a dozen other students, all far more advanced than I, and I worried constantly about making a fool of myself in their grim, driven eyes. Madame Honegger’s method was to concentrate on a different French composer each year. Mine was the year of Gabriel Fauré.

My previous musical education had pretty much stopped with Mozart and Beethoven. Fauré, whose career spanned nineteenth-century French romanticism and early-twentieth-century modernism, was a total exotic. His sonorities were utterly foreign to me. Nor could I discern any logic behind his perfumy harmonies and sinuous melodies. Madame Honegger understood every nuance of Fauré’s music, which she explained lucidly and patiently.

Back on the barge, I would sit at the upright and pick my way through Fauré’s barcarolles, nocturnes, and preludes, hoping that this weird music was getting into my pores. Aided by the rocking of the barge and the romance of the setting, it did. In his album notes, written for my first recording of dance music, George Plimpton recalled the barge piano’s “sharp sad tone, catarrhic from the river mists.” To this day, I hear Fauré’s intoxicating music in the tubercular timbre of that mildewed upright.

Since the barge was without a telephone, anybody who wanted to drop by for a chat or to see Bob on editorial matters showed up without warning. There was always something delicious to eat on the stove—a pot-au-feu, coq au vin, boeuf bourguignon—left by our nautical maid, Josette, who did housekeeping on the other boats along the quai. If she hadn’t prepared something herself, Josette would have brought us a leftover from the restaurant in the Eiffel Tower where her husband worked as the two-star chef.

Late at night, while Bob pored over manuscripts, I’d often be at the piano, jamming with guys I’d gotten to know through the saxophone player Allen Eager. I had first met Allen going into the Café Bonaparte on the Boulevard Saint-Germain to play pinball. You couldn’t miss him: a razor-thin figure in dark glasses with slicked-down black hair and deathly white skin, blowing on his horn at a sidewalk table while a couple of chicks looked on. I sat down to listen.

When he stopped, I offered to buy him a drink, and he accepted. There was something menacing about Allen—he’d been through it all—but I liked his cynical sense of humor. When I told him I was an aspiring musician who lived on a barge down the street, he offered to come over and “show me a few things.” Pretty soon I was learning bebop riffs from the man whom jazz critics were calling “the next Charlie Parker.” One night, Allen said, “Why don’t you come over to the club? The Prez is in town.”

Sooner or later, most of the top American jazz musicians would show up at the dingy, cavelike Club Saint-Germain, much of which was under a sidewalk. Generally, the place was jammed to capacity. But when Lester Young—The Prez—arrived, there wasn’t enough elbowroom to light your Gauloise.

I got there early and was seated up front with a glass of vin ordinaire. Out came five musicians, including Allen and Lester Young. Allen may have been the next Yardbird, but there was only one Lester Young—the most lyrical tenor sax man who has ever lived. Nearing the end of his life, he played with immense reserve, the notes leaking out of him as though he were barely breathing. He was in Paris for a month, and I heard him every night. On the fourth or fifth evening, I arrived early and ran into Allen.

“Hey, man,” he said. “Rene’s out for the evening. Can you sit in?”

This was what I’d been waiting for. René Urtreger, the French pianist, had gotten sick, and they needed a replacement. Allen introduced me to the guys, including Lester, who nodded indifferently under his porkpie hat. The moment we started, the butterflies left me. I’d never played with musicians anywhere near this level. They were so immersed in what they were doing that everything else completely vanished, replaced by a huge, complex universe of mysterious glances, gestures, and musical instincts.

Socially, most jazz musicians seem shy to the point of muteness. But it’s only because words are not generally their medium. Jazz, with its peculiar song lines, rhythms, and improvisatory quality, is their conversation. Unlike classical or popular players, jazzmen aren’t performing someone else’s music, they’re making up their own as they go along. They like to talk about what they do as getting inside each other’s heads. That night, I learned what they meant.

Afterward, Allen said, “You did OK, kid.” The Prez nodded before disappearing into a halo of smoke and a tumbler of Scotch. Arriving home around four in the morning, I couldn’t sleep. I sat outside on the deck under the stars and relived the whole night—the melodies, the rhythms, the riffs, the whole fantastic business of getting inside each other’s heads.

I sat in with Lester and Allen on a few more occasions and decided that the jazz life was for me. Not that I contemplated deserting Madame Honegger, but one day I did ask Allen whether he thought studying classical music was useful for jazz.

“Sure, man,” he said. “Good music is good music. Those cats like Bach and Beethoven wrote some incredible stuff. I dig that as much as anything else. Learn it. Use it.”

Ginny had said that once a week I could drop off my sheets, towels, pillowcases, and underwear in her laundry room. I’d arrive at Number 13 around noon, sack slung over my shoulder, hoping she’d invite me to join her lunch party. If she didn’t, I’d sneak into the kitchen, where Leon would feed me leftovers. Ginny’s most sensational dish was a kind of cheese soufflé. As tall as a chef’s toque-blanche, the soufflé contained poached eggs that were suspended at different levels like Christmas ornaments.

Ginny was determined to expand my cultural horizons. Besides modern paintings, her great love was classical music. Since the war, she’d spent every August at the festival in Salzburg, after which she, Anita Loos, and an English pal, Lady (Foxy) Sefton, would rid themselves of their excesses in the Tuscan baths at Montecatini. Brose wasn’t much of a music lover, and Ginny made it a point to invite me to the important concerts in Paris. One day she invited me to a recital of German lieder by Elisabeth Schwarzkopf. I didn’t know who Schwarzkopf was, and the idea of sitting through an evening of musty romantic German art songs was not at the top of my list. But I said I’d go and had one of the most extraordinary musical experiences of my life.

Le tout Paris was waiting for the first appearance since the war of the soprano who had been one of Hitler’s favorite songbirds. They were prepared to slaughter her. There was much advance speculation about what program Schwarzkopf would sing, and when she announced it would be all German, the knives were sharpened. The Salle Pleyel was packed, everybody dressed to the nines. She kept them waiting. Then she glided out: a blonde ice goddess in a blinding white and gold dress. She was greeted by a smattering of applause and a few catcalls. With scarcely a glance at the audience, she stepped into the crook of the piano and began.

The response to her first group of songs—Schubert, I think—was tepid. With the next group, the temperature rose. And rose. By the time Schwarzkopf reached the intermission, the French were screaming in ecstasy. At one point, Ginny’s hand clutched mine. “You’ll never hear anything like this again, darling,” she whispered.

I was lost in the beauty of the voice, the euphoria of the audience, and the indomitable presence and beauty of Schwarzkopf. Perhaps only the French could have been so quick to forgive the past, prompted by the power of art. Even Schwarzkopf’s encores were in German. The French loved them.

I was living in a dreamworld. In a letter to Harry and Axie Whitney about a weekend I’d spent at Gill and Teddy Goldsmith’s country house, I rhapsodized:

I’m sitting at a very good friend’s house in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, looking out the window at a long valley punctuated by spotty red French roofs of presumably peasant houses. Occasionally a spire reaches up, amidst green trees and housing developments, as if recalling an older slower world: Beethoven’s “Les Adieux” piano sonata, with its octave jump in the melody. Never has an octave jumped to such perfection. The room is gray with the day, as light spats of rain sputter on the window. Several stuffed birds curiously sit on their stands, inanimate, yet swaying in the breeze which comes through the open window. It is spring, and so smells the breeze…it smells of pick-axed gardens, rotting stones, a flower smell, a cooking-pork-with-garlic smell, and the busy smells of life in the Saint-Germain valley.

Beethoven, if anyone, makes me write badly. I feel him so intensely that I can really say nothing but small banalities compared to my true feelings of him. A sip of whisky and soda….

It wasn’t all Beethoven and stuffed birds. Bob and I had a battered old radio, and we listened to Radio Free Europe. That was the winter of the revolution in Budapest, which had been swiftly crushed by the Soviet Army. For days we talked about taking off for the Austrian border to help out at the Red Cross stations where the Hungarian refugees were pouring in. Instead, they came to us. One morning, we found dozens of Hungarians asleep on the quai. The next morning, some of them made it onto our deck. For several weeks, we ran a soup kitchen, dishing out nourishment prepared on our stove by Tom Keogh, The Paris Review’s house artist.

Perhaps the first portent that my idyll was coming to an end was the great flood that seized the Seine in the spring of 1957 after a week of torrential rains. The waters rose to the elbows of the stone Zouave soldiers on the Pont de l’Alma. Old-timers said it was the worst flooding since 1910, when rowboats had been out on the Place de la Concorde and the Zouaves had been up to their necks in water.

Bob Silvers (below left) and me at a party in New York in the sixties (photograph by Jill Krementz). He and I both abandoned Paris around the same time, giving up the barge on the Seine (above), which was anchored just down the street from the Crazy Horse Saloon.

The current was swift and angry. Thanks to the advice of a neighbor, we anchored the barge midstream so that it wouldn’t land on top of the quai when the water receded. From there, we stretched a line to a tree so we could pull ourselves ashore in the dinghy. The line also acted as a conveyor belt over which friends would pull baskets of supplies. Teddy and Gaby Van Zuylen sent particularly splendid pâtés, wild game, and wines.

As the waters raged, we were terrified that the old vessel wouldn’t survive. If the rusty anchor came loose, our next stop would be the very solid stone of the next bridge. Leaving the boat was as scary as staying onboard, since to get ashore we had to lower ourselves into the leaky dinghy and go hand over hand along the line to the quai.

One morning when Bob was setting forth on an errand, the dinghy slipped out from under him, leaving him dangling above the Seine in my Hotchkiss sweater. Bob was hardly cut out to play Harold Lloyd, but he managed to get himself ashore, to great cheering from me.

For a week we lived in this biblical state, fascinated by the debris that floated past: all kinds of furniture, thousands of wine bottles, and one dead cow.

Mait had written to say that he and his Swedish bride, Anne, would be arriving in early summer. He thought it only right that they take over the barge. Bob left to stay at Ginny’s. I daydreamed that Mait, Anne, and I would share a life together. When I mentioned this to Ginny, she said, “I hardly think that’s what they have in mind.”

The end came one day in the first week of June, at about eleven in the morning. I’d been up most of the night with a beautiful young woman who was now lying next to me. Both of us were naked and asleep when a rap on the hatch jolted me awake. I jumped out of bed and slid back the cover.

The first thing I saw was a pair of black wing-tip shoes; the next thing, a pair of pin-striped, blue trouser legs. Finally, the face of Ave in his gray fedora, squinting down at me in my nakedness.

“How are you, Petey?”

“Ave!” I said, grabbing a towel. “What are you doing here?”

“I’m here for some meetings. Thought I’d stop by to see when you’re planning to go back to Yale.”

For a moment I blinked. Then Ave reached into his pocket and said, “I’ve got a prepaid ticket for you, right here.”