14

14

SOCIETY BEAT

The trust fund my father left me had provided just enough to educate me, keep me clothed, and offer a small allowance. But I had no means of real support and no direction. The old doors were still open—Ma and Ave’s, Chiquita’s, Harry and Axie’s—and I went running back to all of them. During my first months out of the Army, I devoted myself to seeing old friends, meeting as many new girls as possible, and waiting for the day when my hair would be back to its former length.

One day, Ma took me to Toots Shor’s for lunch. “Sweetheart,” she said, “I don’t want to interrupt all the fun you’re having, but I think it’s about time you got your ass in gear. You need your own place, and you better start thinking about what you’re going to do with your life.”

I nodded sorrowfully.

The conventional thing would have been to get myself a place on the white-bread Upper East Side, as my friends were all doing. But then, through a beautiful, anorexic dancer I was dating, I heard about an apartment in the Carnegie Hall Studios. What could be better than living over the world’s greatest concert hall?

My ninth-floor apartment in Carnegie Hall was essentially one big room with twenty-two-foot ceilings, a wood-burning fireplace, a functional kitchenette, and a little flight of stairs that led to a sleeping loft. Huge windows faced north over a flat roof. I bought myself a cheap bed and a pair of bookshelves. From the big house at Arden, Ma chipped in an old refectory table and a set of chairs. Chiq sent up a couch and Dad’s favorite rocking chair from her farm in Maryland. Best of all, she sent up his old Bechstein baby grand, the one John Wanamaker had given him when Dad was starting out.

Most of the studios in the tower above Carnegie Hall were used as work spaces by musicians, dancers, and photographers. A few of them had been converted for living. I quickly became friends with two neighbors—the jazz pianist Don Shirley and the cabaret entertainer Bobby Short.

Talk about style: Don, urbane in black from head to toe or an elegant African dashiki; Bobby, the casually tailored gentleman in his houndstooth jackets and handmade shoes. Don and Bobby both worked like hell. Bobby was singing Porter, Coward, Arlen, and Rodgers and Hart at the Blue Angel. Don was playing jazz at places like the Hickory House. Somehow they made it seem as though all they were doing was having a hell of a lot of fun.

Many nights when I crawled home, my phone would ring, and it would be Bobby or Don saying, “How about a nightcap?” I’d lower myself out the window and creep across the roof. There, in Bobby’s or Don’s apartment at two or three in the morning, would be quite a few of the hippest people in New York, having a ball.

One night before Christmas, I’d arrived home with a girl, ready for the sack, when Bobby called. “Come on over to Don’s. We’re having a Christmas party.”

It was 2:30 and snowing. My date and I climbed out the window and put our heads against the wind. We knocked on Don’s window. When it opened, our ears were flooded by a choir of angels. Standing around the piano and belting out “Joy to the World” were Leontyne Price, Odetta, and Martha Flowers, the gospel queen. While we made ourselves invisible in a corner, they went on to “Adeste Fideles,” “The First Noel,” “Hark, the Herald Angels Sing,” “O Little Town of Bethlehem,” and “Silent Night.” By the time they got to “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” nobody in that room had any doubts about the Second Coming.

There was a comforting sense of community in the Carnegie Studios. I’d leave my door open so I could watch the ballet dancers trooping past in their comely, purposeful way. Every day, I had lunch downstairs at the Russian Tea Room, which came to feel like my own dining room. I could depend on seeing friends or famous faces—Leonard Bernstein or Tennessee Williams, or Ruth Gordon and Garson Kanin, who were there every Thursday for pelmeni, the dumpling soup that reminded me of Grandma Duchin’s kitchen.

I became friends with Sidney Kaye, the restaurant’s owner, who took me to a seder at the house of his brother-in-law, the great tenor Jan Peerce, who sang the service. I was knocked out by it. Peerce told me that he’d known my father when they were both starting out—Peerce as a street violinist. To my embarrassment, I had never been to a seder before. I’d heard a bit about the Jewish faith from Aunt Lil and Uncle Ben, but I’d never thought it had anything to do with me. Occasionally, I’d been curious enough about religion to wander into a place of worship, but only to see the architecture or hear the music. I was a mongrel then, and I’m a mongrel today. I’ve never felt the slightest impulse to align myself with one way of looking at the world. Still, I can tell you that, for warmth and drama, a seder sure beats the Episcopalians.

One of my dearest friends at the Russian Tea Room was a Chekhovian Russian waitress named Nadia. There were two “boys” she favored: “my Pyotr and my Rudy”—me and Rudolf Nureyev. Rudy and I developed a waving relationship across the room as Nadia bustled back and forth, making sure we finished our borscht and blintzes, and tweaking our cheeks for being “good boys.” On Russian Easter, she would tap on my door with a Russian Easter cake she’d baked specially for me, and I’d invite her in for a quick shot of iced vodka.

For my first Thanksgiving, I invited twenty-five strays. I called up a caterer and ordered a turkey, all stuffed and ready to pop into the oven. Just before it arrived, my bell rang and my current girlfriend arrived, ostensibly to help out. “Open your mouth,” she said cutely.

I did, and she dropped in a little tablet.

“Now swallow.”

I did.

“Congratulations, Peter,” she said. “You’ve just taken mescaline. It’s going to be an interesting Thanksgiving.”

Fortunately, the bird arrived before my head exploded. As I got the turkey into the oven, I began to feel a little weird, getting the odd flash of magenta where it should have been brown. “How the hell do you expect me to get through this?” I said.

“Relax,” she said. “I’m starting to feel it, too. God, it’s beautiful!”

She suddenly turned into a mallard. “Maybe you’d better fly upstairs to the bedroom,” I suggested.

The guests arrived. Somehow the drinks were poured and the turkey got cooked and eaten. I was in a nonstop horror movie. Why was everybody bursting into flames or turning into a skeleton? When they opened their mouths, why did worms come out? I was sure that at any minute the mallard would come flying over the banister and land in the sweet potatoes. The weirdest thing was that nobody seemed to notice anything the least bit strange about me. But how would I have known?

In the late fifties and early sixties, all of Manhattan was open to anybody at any hour. After work, people would put on their best duds and hit the town. Live music—music you could really listen to or dance to—was everywhere. All the top hotels had supper clubs featuring great house bands led by pros like Emil Coleman or Ted Straeter. For exclusiveness you went to El Morocco, the Stork Club, or Gogi’s La Rue. There was jazz up and down Fifty-second Street and all over the West Village. Tito Puente and Prez Prado were at the Palladium. Later on, you’d taxi over to hear Bobby Short at the Blue Angel, and then cross the street to the RSVP to listen to the Mother of Them All, Mabel Mercer. Or keep on going all the way up to Harlem. At two in the morning, the Red Rooster, Minton’s, and Smalls’ Paradise were just getting started.

A great friend of mine was the poet, actor, and former champion track star Roscoe Lee Browne. Roscoe was appearing in the legendary production of Genet’s The Blacks that completely transformed the New York theater by bringing in a whole generation of great and previously little-employed black actors, among them James Earl Jones, Lou Gossett, Cicely Tyson, and Roscoe.

Behind his extravagant manner, Roscoe had a sharp intelligence. Like me, he walked through all sorts of worlds—jazz, theater, opera, Harlem, Park Avenue. He was the sort of person I’ve always admired—self-created and without boundaries. He loved to share his friends, which is another quality I admire. Best of all, Roscoe was pure theater—on about ten different levels at once.

With a friend, the actress Anna Maria Alberghetti, at El Morocco in 1961.

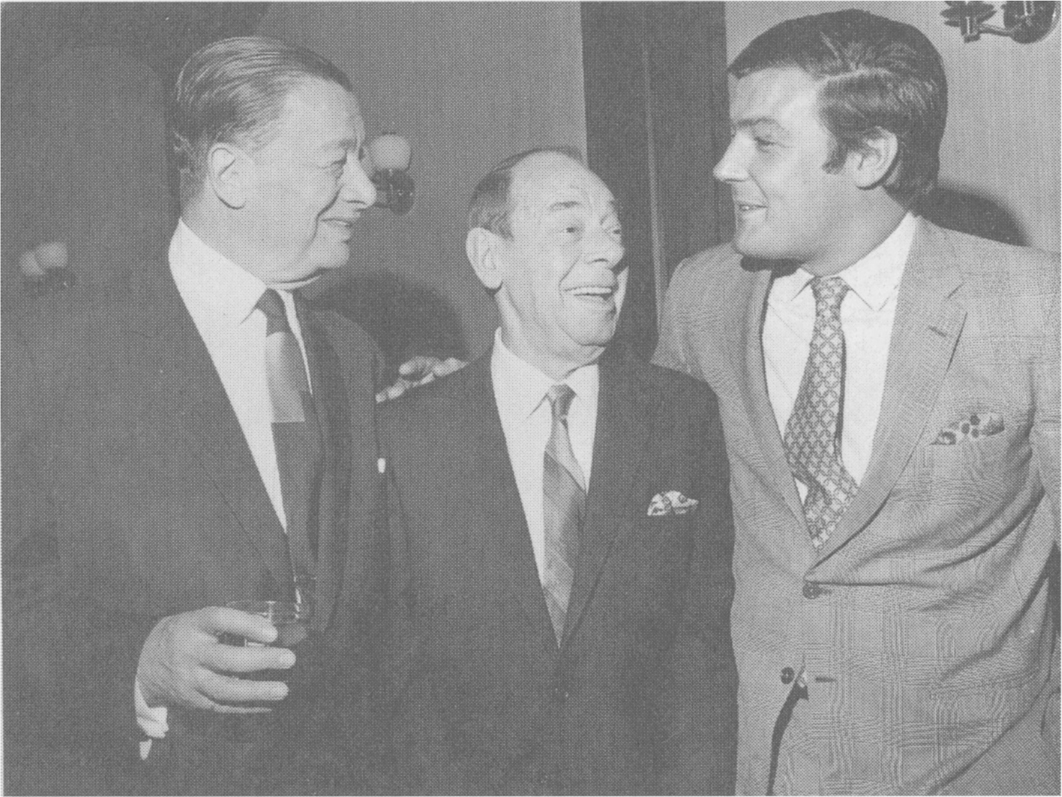

With Toots Shor and Joe E. Lewis. Toots was enormously important in my life. He was an old friend of my dad’s, and a warm and generous friend to me.

Over lunch the other day, we both got a little nostalgic. “There was so much nightlife in New York back then,” Roscoe said, rolling his eyes. “People drank and smoked and stayed up as late as they liked. You could get anything to eat at any hour. Women wore real jewels, and men wore silk. You could even make love in Central Park without getting killed.”

“Who the hell did you make love to in Central Park?”

“I’ll never tell.”

Nothing over the years has changed more than the music business. Jazz may be having a resurgence. It’s always having a resurgence. But there is almost no place in New York where you can dance to live music. Now, everything’s disco—canned and faceless. If I were thinking about starting out in the band business today, I wouldn’t do it. Back then, when you decided to become a musician, it wasn’t just a job, it was a life.

Of course, doors were open to me because of my name and connections. One call to Bobby Brenner at MCA, and it wasn’t long before I had a career, at least on paper. Not that there was anything else on the horizon. Thanks to Hotchkiss, Yale, and the Sorbonne, I had acquired a healthy degree of intellectual curiosity. But that didn’t get you a job. Sometimes I dreamed about returning to Paris and leading the Left Bank life. But deep down, I knew I needed more security.

Other times I fantasized about becoming a serious composer. Ma had always tried to steer me in that direction. “For Chrissake,” she’d say, “you’ve been educated for it. Why don’t you go to Juilliard and get serious?” But every time I thought about sitting down and doing it, I’d let something distract me. Writing really good music means creating a universe of one’s own in sound. I wasn’t sure I had such a universe inside me. And I knew I wouldn’t be able to stand the isolation.

I sometimes think I might have made a good symphony conductor. But again, something held me back. Perhaps it was wanting too much to be liked—which is not a good thing when you’re standing in front of a hundred brilliant musicians trying to get them all to play it your way. I don’t think Toscanini, Szell, Karajan, or Solti ever worried for a second about being liked.

Many people have asked me whether I would have become a bandleader if my father had remained alive. The answer is “Probably not.” I’m sure that if my father had been alive and thriving in 1960, I’d have thought more than twice about following in his footsteps. But he wasn’t around. As I thought about what I could do with myself when I was twenty-three, I realized that the only thing I had to hang my hat on was his legacy. Not that I wanted to be Eddy Duchin all over again. That was impossible. I simply wanted to use whatever talent and personality I had of my own and make the most of it.

If I had any qualms about “selling out” by pursuing a career that others might think frivolous, they were quickly swept aside by Bobby. He had it all figured out. “This is a terrific time for pianist-bandleaders,” he said. “Look at Roger Williams and Floyd Cramer. You wouldn’t believe the records these guys sell. It’s MOR—middle of the road. First we launch you with a recording deal. You with some terrific studio guys. Then we cut an album. We get a record promoter—Jim McCarthy’s the best in the business. We get a movie contract with Universal. Than we get you a band. Pete, with your name and looks—not to mention talent, of course—it’s a piece of cake. Trust me.”

“What kind of music do I play?”

“I told you. MOR. Romantic. Melodic. Your dad’s kind of stuff, updated.”

“Jesus, Bobby, I hate that crap. How about if I do it with a jazz feeling?”

“Forget it. Nobody buys jazz. The name of the game is MOR. Trust me.”

I did.

There was something very comforting about this little guy’s belief in me. Bobby was a fountain of ideas. Beginning in the winter of 1961, we met regularly in his office to plot my rise in show business. I loved the feeling that I was being molded, just as I had when Bill Kitchen had taught me how to fish or when Ave had showed me how to execute a perfect figure eight on my strawberry roan.

I had a lot to learn. Although I could improvise my way through quite a few pop and jazz standards, I had never consciously developed a style, certainly not one that could be considered commercial.

“Take a few lessons from Ira Brandt,” suggested Bobby. “He’s one of the best lounge guys in the business.”

Me a lounge guy? I winced. But I came to love working with Ira. He was a natty little guy with the pencil-thin mustache of an old-world Jewish tailor. He knew every tune ever written. Twice a week, I’d report to his apartment on Central Park West to learn the right touch for Gershwin, Porter, Berlin, Rodgers and Hart, Jerome Kern, Vincent Youmans, Johnny Mercer, Hoagy Carmichael, Harry Warren, Harold Arlen, Burton Lane, Jule Styne, Cy Coleman, Henry Mancini, and so on. I learned the accepted chord progressions used by professional musicians. Going through the tunes over and over again with Ira, I learned how to play less percussively, how to sing the melody with the right hand, even in the bass clef, like my father.

It was from Meyer Davis, the dean of society bandleaders, that I learned how to make people get up and dance. Meyer had been a great admirer of my father. When I called him one day and told him what I was up to, he couldn’t have been more generous about sharing the tricks of the trade.

“Peter,” he said, “when I started out in this business, I was playing for a lot of rich Philadelphia Wasps—Wideners and Wanamakers, people like that. I noticed they all had one thing in common: They had no rhythm. They couldn’t waltz. They couldn’t rumba. They could hardly fox-trot. One day it occurred to me that at least they could walk. I thought, What if I play everything in march tempo? So that’s what I did, and it worked. You know why? Because march tempo is the same as the human heartbeat.”

Meyer was right. Today, I play all kinds of tempos—slow ballads, waltzes, sambas, rock and roll. But the one that never fails to get them up on their feet is still the old Meyer Davis heartbeat.

Under Ira’s tutelage, I practiced various exercises to become more technically fluid. I’d dissect the most familiar standards like a medical student in anatomy class. Ira would have me play “Blue Moon” upside-down, sideways, and backwards. It was the only way, he said, to really get all the possibilities into your fingers. After six months of this, I had mastered some 300 standards, including “Here Comes the Bride” and “Havah Nagilah.” Today, I’ve got about 3,000 tunes in my fingers.

A bandleader sometimes has to play solo background piano during the cocktail and dinner hours, so I started dropping in at the Drake Hotel to hear Cy Walter, the top cocktail stylist in the city. Cy played the simplest tunes in the most complicated arrangements, everything in sharps and flats. Without injecting any jazz feeling or deviating much from the melody, he was never perfunctory or boring. With his great technique and inventiveness, Cy turned everything into a little rococo masterpiece. He was proof that you could play in the melodic style without being square.

Bobby also urged me to study my father’s old recordings. “Not to copy him,” he cautioned, “but to learn why people wanted to listen to Eddy Duchin all night.”

For my taste, Dad’s style was too ornate. But as I listened to his records, I understood why so many people had always said they felt he was playing only for them. Dad hadn’t just played the melody, he’d played the lyrics, as though he were singing the song in his head.

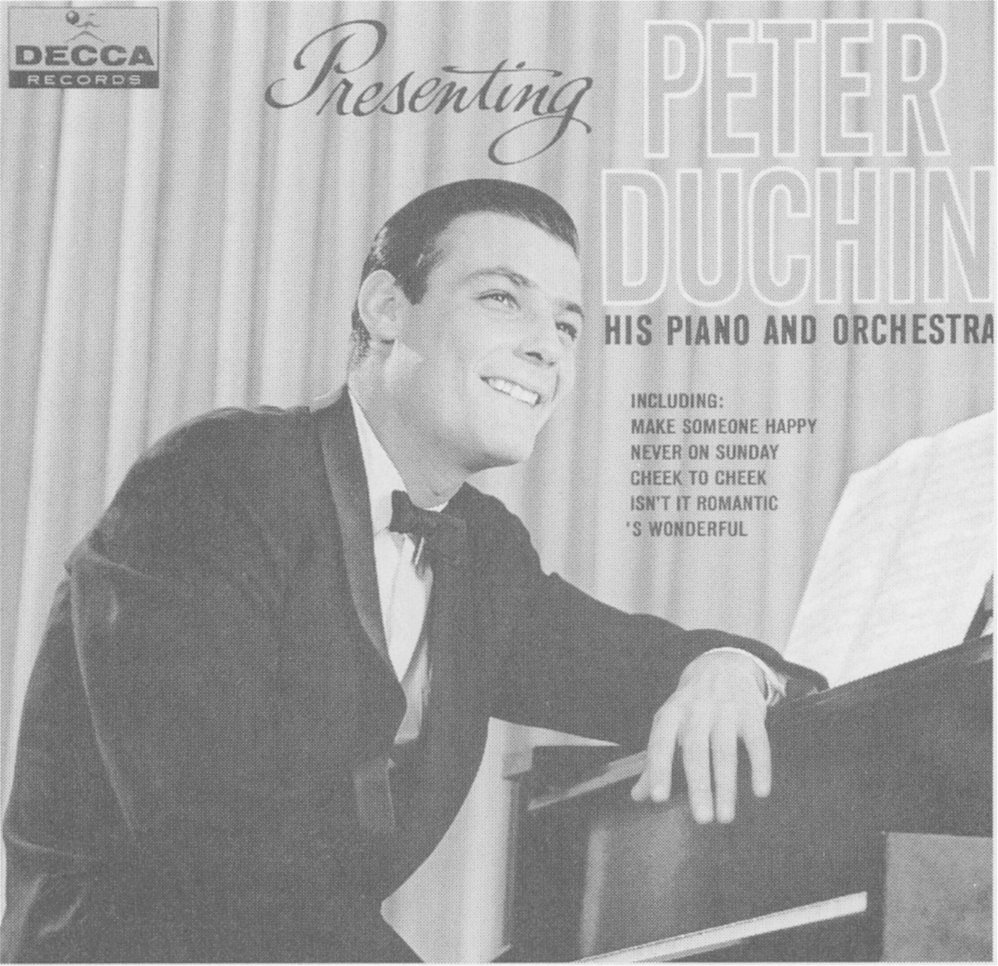

The people at Decca Records had done extremely well with the soundtrack album of The Eddy Duchin Story (with Carmen Cavallaro sitting in for my father). I may have been completely wet behind the ears, but the commercial chances of an album featuring Eddy Duchin’s son were too obvious to resist. It also didn’t hurt that Bobby and I were putting together the whole package, including a movie deal. In a matter of weeks, Bobby got me a five-year contract with Decca, calling for the release of two albums a year.

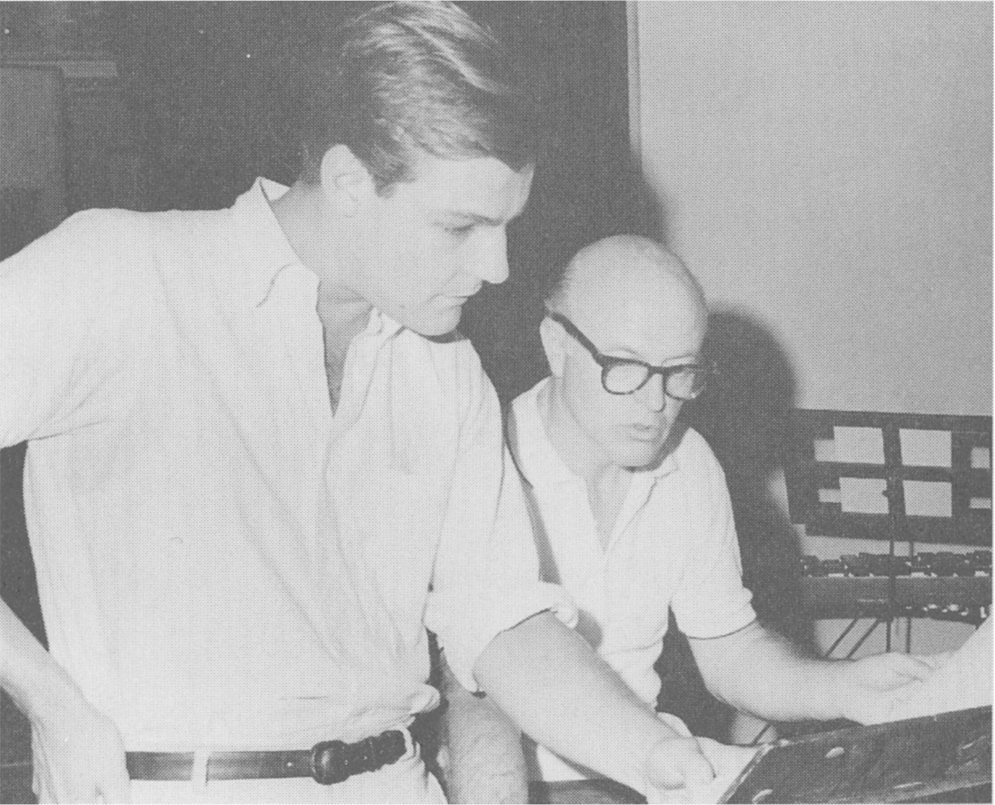

For an arranger, Bobby hired one of the best in the business. Henri René was an elegant, classically trained European who had written for Hollywood, nightclub acts, and recordings. He liked the idea of working with a neophyte, someone who would be putty in his hands. For three months, we met at his place or mine, exploring the possibilities of each tune, including what I would play, note for note.

Listening again to that first album, I wish I’d had the courage to inject more of my own personality and feelings into the arrangements. It might have been too jazz flavored, but it would have been less bland. Even so, Presenting Peter Duchin received a lot of radio exposure as well as excellent reviews when it was released in February 1962. It sold surprisingly well—over 100,000 copies. The repertoire included tried-and-true standards, selections from the best musical of the day, Bernstein’s West Side Story, a pop arrangement of Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” (as a lush ballad), and the theme from Never on Sunday, the hot art movie of the moment.

All my backup musicians were top studio guys, and Henri’s arrangements were tailored to create a style that was intimate but not too personal, bouncy but not too jazzy. The first cut, “Make Someone Happy,” written by my friends Jule Styne, Betty Comden, and Adolph Green, got the most airplay. It would become my signature song when I opened at the Maisonette.

In March 1961, George Plimpton invited me down to Florida, where he was staying with Harold S. (Mike) Vanderbilt and his wife, Gertrude. George was working on a profile for Sports Illustrated of this most distinguished of Commodore Vanderbilt’s many descendants. The last of his family to sit on the board of the New York Central, the railway founded by his grandfather, Mike was perhaps the greatest figure in American yachting (he’d successfully captained several America’s Cup winners), as well as the inventor of contract bridge, which he had refined from an earlier game called écarté during a long and boring transatlantic crossing in the twenties. He was famously shy, and I was surprised that this tall, straight-backed, quiet man with a scholar’s face was so friendly when I arrived at his palatial estate in Lantana, just south of Palm Beach.

My first album was released in February 1962. The first cut, “Make Someone Happy,” became my signature song at the Maisonette later that year.

Henri René was the arranger for Presenting Peter Duchin and several subsequent albums.

After dinner I found myself in a book-lined den that housed an astonishing collection of pigs made out of every substance—china, stone, metal, precious gems. “Mike was a member of the Porcellian Club at Harvard,” whispered George, who had also belonged to the club. “He was obviously quite taken with the symbol.”

Mike pulled me aside. “Perhaps you didn’t know this, Peter, but we’re related.”

This was unexpected—and very good—news.

“Well,” he explained, “my mother’s sister was your great-great-aunt Theresa Fair Oelrichs. Hasn’t anybody ever told you about your Newport family?”

“Not really.”

Mike remembered my mother well. “She was an interesting woman, with an unusual style,” he said, adding cryptically, “She was ahead of her time.”

Staying at Mike and Gertie Vanderbilt’s was just about the most luxurious experience of my life. Their many servants were scarcely seen or felt. George and I were assigned a valet, a dark, diminutive fellow whom we nicknamed “the Bat” because of his black suit and big, pointy ears. Whenever we dropped our clothes on the floor, the Bat would appear as if by telepathy and whisk them away to be washed and pressed.

One afternoon as we were dressing for tennis, I heard a roar from George’s room. I found him on the floor, convulsed with laughter. “You’ll never guess what the Bat did,” he said. “He found my jockstrap, and he not only took it away and cleaned it but pressed and starched it. It’s impossible to put on.”

Like Bill Kitchen, Mike was immensely methodical, concerned with doing things right. A couple of years later, George and I had lunch with him at his apartment in the River House in New York, and I was surprised when Mike got up from the table, went over to the sideboard, and started tossing the salad. He went at it for quite some time, very deliberately, as though he were performing a chemistry experiment. “Seventeen times,” he explained. “That’s what my mother always told me about tossing a salad. Seventeen times.”

Mike was generous with his knowledge, particularly about contract bridge. George and I knew the rudiments of the game, and Mike took great delight in explaining to us the various conventions he had developed, as well as the defensive strategies, of which he was the acknowledged world master. One rainy afternoon in Palm Beach, he invited us to sit in for a couple who had canceled at the last minute. Our fourth was one of his extremely rich neighbors.

“What should we play for?” said the neighbor.

“How about five cents a point,” Mike said.

George and I looked at each other in horror. At that level, we could easily lose our entire net worth in a single game. Noticing our expressions, Mike said, “We’ll have the boys play for a tenth of a cent.”

By the end of the afternoon, Mike was several hundred dollars in the hole. Waving the invisible, aged butler over, he said, “Charles, would you please go upstairs and get my money?”

“All of it, sir?” said Charles, perfectly deadpan.

“Oh, I don’t think so,” replied Mike with the hint of a smile.

The other night I had drinks with my first wife, Cheray. When I asked her what I’d been like when we met at a dinner party that spring in Palm Beach, I wasn’t surprised by her answer:

“I’d heard a lot about you, and you had a perfectly terrible reputation as the sort of man who breaks a girl’s heart and never calls again. You were exactly what I wanted nothing to do with. But I have to say that I was pleasantly surprised.”

A tall, graceful blonde with a clotheshorse figure, Cheray has two qualities I admire: she’s a great listener, and she’s genuinely down-to-earth. Before Cheray, I had done most of the listening. I had always loved hearing women talk about themselves. Years of coming home to the Harrimans’ late at night and finding Ma still up, sipping her vodka on the rocks, puttering around the house, emptying ashtrays and ready to “dish” until dawn, had taught me how to listen. I knew what questions would bring out a woman’s confidences, a talent I developed not out of malicious curiosity but as a way, perhaps, of building my own self-esteem.

Except for Sally, I hadn’t been terribly interested in women my own age. Once the sex was over, I’d found most of them silly and narcissistic—either too conventional or not worldly enough. So I had dropped them and moved on—without giving a damn about their feelings. Whenever things got messy, or even when they didn’t, I split.

Cheray was one of the first women my own age with whom I felt comfortable enough to talk about myself. Turning to her that night on the jasmine-scented terrace in Palm Beach, I opened up. Prodded by her low-key, patient interest, I found myself telling her what little I knew of my family background, as well as my views on art, literature, and politics.

“You were different from the other boys,” she reminded me the other day. “You’d been out in the world. Instead of talking about your career or the tennis game that afternoon, you talked about things outside yourself, especially books. At first I thought, Here goes—my turn for the Peter Duchin charm. But you were more than that. You were interesting. I even remember the book you were reading: The Air-Conditioned Nightmare by Henry Miller.”

The morning after that dinner party, I woke up infatuated. At breakfast, I mentioned to Mike that Cheray had invited me to join her at Lyford Cay in Nassau, where she was vacationing with her parents. Mike said, “Why don’t you fly over? And by all means, use my plane.”

Mike Vanderbilt’s private plane wasn’t something you turned down. Cheray was waiting for me at the Nassau airport. That evening I met her parents, George and Audrey Zauderer, who greeted me as though I were already part of the family. After dinner, Cheray and I ventured into the center of the island. At a big, open-air nightclub, I jammed with a local band that was playing its own version of rhythm and blues. It was a throbbing, sexy, tropical night, people dancing, swaying, boozing. Cheray sat on the bandstand in a simple cotton dress, barefoot and at home. I had been telling myself that the last thing I wanted was to get involved. But that night, it occurred to me that maybe this was a girl I could get serious about.

In September 1962, I opened at the Maisonette in the St. Regis, and suddenly had a career.