15

15

AT HOME IN THE ST. REGIS

One night I was taken to dinner at Cole Porter’s apartment in the Waldorf Towers by Maria Cooper and her mother, Rocky (Mrs. Gary) Cooper. A terrible riding accident had left Cole a paraplegic, and he lay on a chaise longue, looking damaged and fragile in a silk smoking jacket. He remembered my parents fondly, as well as his old house on the Rue Monsieur, bought by Ginny after the war. Everything was going splendidly until he turned to me after dinner. “Peter,” he said, “would you be kind enough to play me a tune?”

My heart stopped. With shaky, sweaty hands, I sat down at his ornate Steinway and played “Night and Day,” the first time through in my father’s heavily melodic style, the second time with a jazz feeling.

Cole smiled. “That was delightful, Peter. You do have your father’s touch.”

I didn’t believe him.

A few weeks later, I was invited to dinner at the apartment of Mr. and Mrs. Arthur Rubinstein. The great pianist was warm and outgoing, and because his daughter Eva had told him I was starting out on a musical career, he was full of advice. When I asked how aware he was of the audience when he played, Rubinstein replied, “Immensely. To play my best, I must have an audience. It’s a good idea to play for one person—for me, a beautiful woman. One time in Denmark I played the whole concert to a woman in the back. I played to her as though she were the only person there. Afterward she came backstage. ‘Maestro,’ she said, ‘I was very honored that you played everything just for me.’ You see?”

Then came the dreaded moment: “Peter,” said the maestro, “why don’t you play something for me? I hear you play jazz. I love jazz.”

I had no choice. I went to the concert grand in the living room as though to the guillotine and got through a couple of choruses of “How High the Moon.”

“Bravo! Bravo!” cried Rubinstein, clapping like a child. “Now I play for you.”

Putting down his brandy and cigar, he launched into a majestic Chopin polonaise with the same improvisatory approach I might have used for jazz. He played it like dance music, which it is. And, as if on cue, his wife and children started dancing around the living room. I sat there enthralled by the joy and exuberance. The combination of the beauty of the music and the earthy domesticity of the scene was breathtaking. That’s how Chopin should be played.

Being in the spotlight as a performer scared the hell out of me, and when Bobby said it was time to get a band together, I was reminded of how unsure I felt about myself. How would I fare in the critical comparisons with my father? All the bandleaders I most admired—from Count Basie to Ted Straeter—had a persona, a public personality. What was my persona?

I had found an old news clip in which my father talked about taking acting lessons to prepare for the films he had appeared in as a bandleader. He said that the lessons also helped bolster his confidence on the bandstand. That my father had felt insecure in public came as a pleasant surprise, and I didn’t need pushing when Bobby suggested that I take acting lessons. “If you don’t feel self-confident,” he said, “you can at least look self-confident.”

My acting teacher was Wynn Handman, one of New York’s most respected younger acting coaches (whom I would later help to found the American Place Theater). In a bare studio, one flight up in an old building on West Fifty-sixth Street, I joined a dozen other students to learn the fundamentals of acting: how to move, how to speak, how to get into character.

I hated it. When Wynn, who was wonderfully soft-spoken and attentive, asked me to stand up and read dialogue, he might as well have been asking me to fly to the moon. My only previous stage experience had been in seventh grade at Eaglebrook, where my turn as a dancing fairy in wings and tutu had brought down the house.

One day, Wynn asked me to read a scene from Molnár’s Liliom with a shy, fragile-looking student named Mia Farrow.

“Peter,” he said, “look into Mia’s eyes as you speak. Try to make her react to what you’re saying.”

Gazing into those beautiful eyes, I saw only the reflection of a jerk who didn’t know what he was doing. I was totally at sea. Mia spoke her lines sweetly and nearly inaudibly. I lumbered on.

Wynn stopped me. “Peter, what do you think the scene is all about?”

“A man trying to make an impression on a girl, I suppose.”

“OK. Try doing that to Mia. This time use your own words.”

I did, and I began to see what he was talking about: Acting is as much about the actor as about the character. Encouraged, I really came on to Mia. She laughed, and we both broke up.

“That’s even better,” Wynn said. “Because it’s real. That’s what you want to be onstage.”

In the course of my year in Wynn’s classes, I came to enjoy them enormously. I never was much good, but once or twice I felt I’d succeeded in becoming the character. I learned that—paradoxically—you have to lose yourself in order to become yourself. It was exactly the self-confidence I was looking for.

To celebrate the release of my first album, Chiq and Bob invited me to Madrid, where they were living in a fantastic apartment on the Plaza Major. Chiq went to memorable lengths to entertain me. I had done a lot of shooting in my time, but nothing had prepared me for the shooting party we all went to one weekend at a great estancia outside Madrid.

I showed up in jeans and sneakers, the Spanish aristos in tailored tweeds and handmade boots. Raising their well-defined eyebrows, they looked down their tapered noses at my American slovenliness.

Everyone had two shotguns and a secretario, whose job it was to load and hand you the second gun once you’d emptied the first one. We were seated on camp chairs arranged in a long line, each shooter behind a “butt,” or enclosure made of hay and grasses tied together, which had been set up as camouflage. A quarter of a mile in front of us was a medieval army of peasants, some on foot, others on horseback, whose job it was to drive flocks of partridges out of the bushes by banging bells, pots, and pans. Between each butt was a tin shield to keep you from being shot by your neighbors. A darn good thing, too, since I’d never seen people so reckless with firearms as these Spanish aristos. I shot very well, ending the afternoon as number-two gun. Suddenly I was no longer the ugly American.

A few nights later, at a flamenco club in Madrid, Chiquita introduced me to the most beautiful woman I’ve ever met. While I tried to look cool, Ava Gardner let go with her great horse laugh and checked me out with her almond-shaped eyes. Before long I was coming on to her, and she was coming on to me.

Ava was as real a woman as I’ve ever known. The pain in her life had outweighed the joy, and she wasn’t afraid to show it. Surprisingly, she had no vanity. She needed no jewels, makeup, or entourage. Apparently, she hadn’t recovered from her breakup with Frank Sinatra, about whom she talked often and fondly. When we got to know each other, she’d make me go to the piano in her living room and play the songs Frank had sung for her. When I played the beautiful Billy Strayhorn ballad “Lush Life”—her favorite—she’d lean on the piano, sing the lyrics very softly, and cry. Then she’d catch herself and say something like, “That chord is wrong.” Or, “You don’t phrase it as well as Frank did.” I felt both protective of her and awed by her. It seemed inconceivable that one of the world’s most beautiful women could be so vulnerable.

She was unpredictable: affectionate and sensual one moment, caustic and confrontational the next. I was half her age, but I must have appealed to her because of my energy, even though it wasn’t quite a match for hers. Every night, five nights running, we hit the flamenco clubs. All the musicians and dancers knew her. The moment she walked in, they exploded. Our fling ended abruptly at seven o’clock one morning when her Ferrari spun out of control on a wet country road. While we whirled to a stop in a hay field, my life passed before me. Ava just laughed and laughed.

It was Chiq who called her friend César Balsa in the spring of 1962 and reminded him of the night he’d heard me play in Mexico City. And she came with me when I made my pitch to César at the St. Regis. As coached by Bobby, I said, “You must be really tired of dealing with the managers of all those different singers you have down in the Maisonette. I’ve got a better idea. Why don’t you hire me and a band for the season? You won’t have any managers to deal with. I’ll bring in all my friends, and they’ll bring in all their friends.” He went for it—hook, line, and Social Register.

On May 31, 1962, I signed a contract to play with my own band at the Maisonette. It called for me, ten musicians, and a vocalist to perform from September through the following June, six nights a week from 8:00 P.M. to 2:00 in the morning, with Sunday matinee as an option. We would receive $2,439 a week for the first four months; $2,717 for the following four. The St. Regis would pay extra for New Year’s Eve, and the hotel could exercise its option for our services the following year, at increased wages.

The fringe benefits were spectacular. I would be given my own suite in the hotel—free. Office space in an adjacent building—free. Dinners at the Maisonette, all the drinks I wanted, and any bottle of wine from one of New York’s great cellars—free. And there would be no cover charge for any of my friends who happened to drop in.

It was the last contract personally signed at MCA by Jules Stein. Out of loyalty to my father’s memory—not to mention astonishment that I would be starting out at the St. Regis—Jules overruled the objections of one of his top executives, Larry Barnett, who thought I didn’t have “what it takes.” MCA had just bought Universal Pictures, which had set off an alarm in the U.S. Department of Justice’s Antitrust Division. Shortly after I signed my contract, MCA became strictly an entertainment producing and distribution company, and the talent agency was dissolved.

The only thing missing was a band. Bobby was friendly with Otto Schmidt, a sax player and clarinetist in Ted Straeter’s orchestra at the Persian Room in the Plaza. Otto, a classy, white-haired veteran, wasn’t exactly hungry. But Straeter was about to retire, and he generously suggested that Otto help me get started. In short order, Otto started rounding up musicians for the fall, five of whom came with me for a warm-up gig that summer.

Despite its fancy name, the Mid-Ocean Bath and Tennis Club in Bridgehampton, Long Island, was as nouveau riche as the people who a few years later would turn one of the nicest resort areas on the East Coast into a zoo. Southampton and East Hampton—bastions of Old Money that had been summering on the East End of Long Island since the 1920s—were zoned against such invasions. But Bridgehampton, a sleepy little in-between village with a couple of antique shops, wasn’t so well protected. It was there that a guy Otto knew, a real-estate developer named Lou Sacher, was putting up a beach club and a development of condominiums. Bobby and Otto had no trouble selling Lou on the new Peter Duchin Orchestra. With my social connections, he’d get the “right people” in no time. In return, the combo and I would get some badly needed on-the-job training.

That spring, Otto gave me a crash course in bandleading. When I wasn’t recording my second album of Henri René arrangements, In the Duchin Manner, I was working with Otto in my Carnegie Hall apartment, putting together a book of songs. Unlike jazz or concert bands, successful dance bands play mostly without music, since they don’t want to break the flow of the evening by fumbling for the arrangements. Dance band musicians have to carry around thousands of tunes in their heads, along with the fundamental four-part harmonies of each song. Learning the repertoire—a vast, constantly growing body of music—is a task usually accomplished by many years of experience. I found that the best way to memorize songs was to write out arrangements of them, however sketchily. By June, I was still shaky on all but a couple of dozen arrangements. But on the day the painters put the finishing touches on the new Mid-Ocean Club, I opened with my own six-piece band.

We did all our learning in public. My Hampton friends would stop by to lend moral support, and nobody seemed to mind when we played “Night and Day” or “The Lady Is a Tramp” four times in a row. Nor did they complain when we’d follow Rodgers and Hart’s “Lover” with a samba, followed by “Let’s Twist Again.” That we were a work in progress seemed to add to the appeal. Playing requests is a big part of the business, and it became great sport among my friends to ask for the most arcane tunes they could think of. But they couldn’t outsmart Otto and the other guys, and I’d stumble along.

A good friend of mine, Geoffrey Gates, a broker with Bache & Company, had rented a beach house with me. It was next to an enormous estate in Southampton owned by Henry Ford, Jr., and his wife, Anne, whose family, the McDonnells, had been around the Hamptons a long time. A jovial roughneck, Henry loved to party all night. He could be incredibly short-tempered and crude, but he was brighter than a lot of people gave him credit for, and he was a lot of fun. One of his endearing traits was that he treated youngsters like me as adults.

Henry was ready for anything. A couple of times, unbeknownst to Anne, I took him to the Hotel James, a funky old establishment on Route 27 with a black clientele and a great rhythm and blues bar in the basement. I made a lot of friends there, and some of them asked me to come by the local Baptist church on Sundays and sit in when they needed a keyboard player. For a half dozen Sundays that summer, I had another learning experience, accompanying the black choir and congregation as they belted out down-home hymns and gospel. It turned out to be enormously useful when, a couple of years later, I had to learn how to play rock and roll.

At dinner one night, Anne Ford mentioned a big party she was planning for the top people in the auto industry, many of whom were flying in from Detroit. Explaining that she’d run out of guest rooms, she asked if I had any suggestions. Jokingly, I mentioned the Hotel James. This broke up Henry, who blew his soup halfway across the table. Anne looked perplexed, but she was used to Henry’s primitive manners, and she filed away the name of the hotel. The next morning she booked four rooms at the James, including one for a top General Motors executive.

I would have given anything to have been there the day the big shot pulled up to the James in his limo and was confronted by the sight of all those black people rocking quietly on the rickety front porch. As Henry later told me with enormous glee, the tycoon raced back to the Fords’ house and screamed, “What the hell! Is this a joke?” Anne, Henry chortled, “went up the goddamn chimney.”

Toward the end of summer, the Fords asked me to play for a party for their younger daughter, Anne, and one of her friends. I was flattered and terrified. Not only would I be fronting a band twice the size of the one in Bridgehampton, but I’d be up there in the spotlight all night long.

“Don’t worry, Pete,” said Otto, “we can handle it. I’ll bring in a bunch of ringers—top guys from Lanin and Davis.”

I knew Otto could handle it, but I wasn’t sure I could. Although I’d been to countless deb parties, I’d never paid much attention to the music. Most of the time I’d been trying to get the girls into the bushes, not onto the dance floor. In fact, it’s always embarrassed me that I’ve never been much of a dancer. And I didn’t have a clue about playing a whole evening. I knew nothing about how to order the tunes, the tempos, or the length of the sets.

Otto said not to worry. He and another musician would call the tunes and decide on the tempos. “I’ll give you the key changes with my fingers,” he said. “For the flat key signatures they go up—one finger for F, two for B-flat, and so on. For the sharps, they go down. One for G, two for D…” He added, “All you have to do, Pete, is look happy, play the right notes. And for Chrissake, don’t leave the bandstand. Knowing you, you’ll never come back.”

The night of the party, it felt strange to be putting on my black tie and thinking of it as a uniform. Stranger still was arriving at the Fords’ house early and parking behind the tent along with the catering trucks. I had walked into many parties exactly like this one before, but it had never occurred to me that the tents had two entrances—one for the guests, the other for “the help.” Tonight, I was the help.

I came in past the pots and pans and liquor and glass cartons. Otto and the other musicians were already there, setting up the bandstand. Otto introduced me around, and a couple of the players remarked that they had seen me at other parties—out front. One of them, a real old-timer, said he’d once played with my father. Nervously, I took out my little folder of arrangements and put them on the piano. None of the other guys had brought along a single sheet of music.

Thanks to Otto’s pacing, the dance floor filled up and stayed that way until two in the morning, when we ended with “Goodnight, Sweetheart.” It was like waves. We’d build in tempo and intensity, then subside to something slow and dreamy. Then build again and subside. For the last half hour, we just wailed while the dance floor rocked. I was drenched with sweat and happy to the bone.

Within a few weeks after I’d opened at the Maisonette, the club was mine—my living room, my rumpus room, my dining room, my stage. The critics loved us. The morning after my debut, The New York Times’s reviewer, Milton Esterow, set the tone: “It seemed as if they could have danced all night….Another Duchin is back in town.”

Two weeks later, Newsweek reported: “Whether drawn by nostalgia or curiosity, the crowds of young and old New Yorkers pour into the St. Regis Hotel’s Maisonette supper club every night to hear Duchin the younger and his eleven-piece orchestra. What they have heard…is a dance band with jazz on its mind. Melody and romance are there, but Duchin has added a rhythmic excitement to familiar tunes and a touch all his own.”

Among some of Dad’s old fans, the jury was still out. The Newsweek article began: “Still ruddy from a steam bath, massage and three or four drinks at his downtown club, the old man two-stepped his way to the edge of the dance floor and over to the piano. ‘I knew your father,’ he told the orchestra leader in a confidential bellow. ‘I knew him in the old, old days out at the Central Park Casino. You know, you’re very much like him. But you’ll have to go a long way to beat him.’ ”

We started at nine and played for forty minutes before taking a twenty-minute break, during which we were relieved by a five-piece Latin group. Forty minutes on, twenty minutes off, with a dinner break at eleven. We stopped at two in the morning.

We soon attracted a colorful cast of regulars. There was the businessman who came in every Thursday night with his mistress and every Saturday night with his wife. The first night, he came over and said to me: “Get this straight. You can say hello to me on Thursday, but you make sure you don’t ever say Saturday that you saw me Thursday.”

There was the high-class hooker, a statuesque brunette with very white skin who came in every night with a different man. We called her—for obvious reasons—the milkmaid. “Peter,” she said in her Teutonic accent, “I like your music and I like this place a lot. But you must always act like you never saw me before, OK?” I nodded, and she palmed me a hundred-dollar bill.

Everybody came in, from mafiosi to the Duchess of Windsor. One night Ava Gardner showed up and handed me a tiny cap pistol. “It makes a noise louder than a bull’s fart,” she said. Backstage, I aimed it at one of the musicians and pulled the trigger. Ava had understated the bull’s fart. The victim smeared his white shirt with catsup, staggered out, and collapsed on the dance floor. The place erupted in screams until I appeared and announced that it was all a joke.

There were lots of big tippers in those days, none bigger than the Arab sheikh who came in one evening with a girl out of the kick line at the Copa. As we were ending one evening with “The Party’s Over,” he reached into his voluminous robes and pulled out an enormous wad of bills, which he proceeded to throw at us like confetti. We accelerated to the last bar, ended with a flourish, and scooped up the cash: more than a thousand bucks in five-dollar bills.

The Maisonette staff became my family. Most of them had been hired by Vincent Astor, who had owned the hotel before César. Vincent had put a premium on old-world manners—as did all the top hotels in New York in those days—and the place still had the feeling of a European grand hotel.

There was Rudy, the impeccable, Austrian-accented maÎtre d’ who glided through the room like a swan. For fun one night, I asked him if he’d start the band with a wave of his hand. Rudy loved it so much that it became a tradition. Every night at nine, he’d stroll out to the middle of the dance floor and announce, “Time, boys! Time to go!” Then he’d give the downbeat, and we’d launch into “Make Someone Happy.”

Not since Chissie and Zellie had anyone looked after my welfare better than Rudy. The royal we was his only pronoun, and before my dinner break he’d come over to the piano and say, “Why don’t we have the striped bass with beurre blanc tonight? It’s very fresh. And what are we going to drink? I think we’ll enjoy the ’53 Montrachet.” If two girls I was taking out arrived unexpectedly, Rudy would make sure to seat them as far apart as possible, tipping me off with a wink and a nod. For these and countless other favors, I called him Mother.

Rudy was a walking Who’s Who of names, faces, and pedigrees. He conferred titles on all the notables. “Peter,” he’d say, “the Governor is coming in tonight”: he meant Ave. Or, “The Producer”—David Merrick—“is coming. I’m sure he’d appreciate hearing something from one of his shows.” Or, “The Artist”—Salvador Dalí—“is in booth number twelve. He’d like you to come over and say hello.”

Dalí, who lived in a suite upstairs with his wife, Gala, was a regular. One night, he handed me a manuscript. “Peter,” he said, in French, “would you be kind enough to translate into English a little poem I have written?” I waited until I got back to my suite to look at it. A dreadful exercise in pseudopornography about a king greatly given to self-abuse, it was called “Le Grand Masturbateur.” I never managed to put it into English or any other language, and the subject never came up between us again.

My last sighting of Dalí was a couple of years later, when I was hired by Rebekah Harkness, the dance patroness, to play for her daughter’s wedding in Watch Hill, Rhode Island. In one of the surrealist tableaux vivants that had been set up for the guests’ amusement, I spotted “the Artist” squirting shaving cream on a group of naked models from a can of Barbasol. I waved at him, but he was so absorbed in what he was doing that he didn’t even wink.

Another of my favorites at the Maisonette was the men’s room attendant, whom we called Jack the Turk. A stocky, swarthy man with a permanent smile, he looked like the swami on the Fatima cigarette packs. Jack maintained a running feud with Anna, the ladies’ room attendant, who was stationed forty feet across the foyer. They pretended not to notice each other, and, according to Rudy, they hadn’t exchanged a word in twelve years. No one could figure out why.

Jack, like Rudy, had his Who’s Who down cold. One night he heard Rudy telling me that my friend Anthony Biddle Duke, whose family had owned the St. Regis before Vincent Astor, had reserved a table for the evening. Jack’s smile broadened. When Rudy asked what he was up to, he replied, “You’ll see.”

During my first break, I went to Tony Duke’s table and found him doubled over with laughter. “I’ve never given anyone a hundred-dollar tip in my life,” he said. I glanced up and saw Jack standing by the men’s room, his grin bigger than ever. Tony explained that when he’d gone inside to relieve himself, he’d found the men’s room in darkness except for a pair of candles burning on either side of a urinal. As he was unbuttoning himself, he heard the silky voice of Jack the Turk: “Welcome home, Mr. Duke…”

Salvador Dalí lived in the St. Regis and was a regular when I was playing at the Maisonette.

Early on, I realized that what would make us distinctive was not to have a particular sound, as did the bands of Count Basie, Duke Ellington, and Lester Lanin. Since I hadn’t developed a strong personal piano style of my own, I made a virtue of eclecticism, and it paid off. The Maisonette was usually filled with people of all generations from all over the country. I wrote arrangements of music from various periods; we even used some of Dad’s arrangements. Being able to play in all kinds of styles—from swing to rock and roll—is still a hallmark of the Duchin bands.

The bulk of our repertoire consisted of a wide range of show tunes, from the twenties to current Broadway shows. Occasionally we played the theme from a hit movie, as well as a few Top 40 tunes. One of the things that made us popular with young people was that I made a point of adding the latest styles when they seemed appropriate. We may have been the first supper club band in New York to play Ray Charles, the Beatles, and bossa nova. When we first played “I Want to Hold Your Hand,” the older people came up and complained that it was too “wild.”

My friends poured in. One night Mother (Rudy) announced, “Ma is bringing in the girls.” (By then Rudy had become so friendly with Marie Harriman that he called her Ma.) “The girls” meant Ginny Chambers, Anita Loos, and Madeline Sherwood. In they came, and by two in the morning they still hadn’t ordered anything but soup and drinks. Rudy, who wanted to close up, eyed me meaningfully as I stopped to say good night and see them to their car.

“I’m hungry, girls,” Mado Sherwood suddenly announced. She waved Rudy over, and he politely informed her that the kitchen was closed. “What about breakfast?” persisted Mado. “I’d sure like to get back into that kitchen and see if we can whip up some buckwheat cakes. I’ve made some mean buckwheat cakes in my day. Come on, girls.”

We all trooped into the kitchen, where everything was locked up for the night.

“Where’s the buckwheat?” demanded Mado.

Rudy said he’d have a look in the cellar. He disappeared and a few minutes later returned with all the necessary ingredients, plus a half dozen bottles of the best champagne in the house. At three in the morning, Ma, Neetsie, Ginny, Mado, Rudy, and I sat down to a breakfast of buckwheat pancakes and Dom Pérignon.

Another night, Jule Styne, the composer of Gypsy, Bells Are Ringing, and many other terrific shows, arrived halfway through the first set. With him was a familiar-looking man whom I couldn’t place. The way they both kept staring at me made me nervous. During the break, I went over and asked Jule what he was up to. He introduced his friend as the playwright S. N. (Sam) Behrman and asked me to sit down.

“You did fine.” Behrman smiled. “You passed.”

“I did?”

“We wanted to see if you were good enough to play Gershwin in a new musical we’re writing about him. You are. Would you be interested?”

I was more than interested. Dad, who had looked far more like the composer than I did, had almost played Gershwin in the movies. Now I would—on Broadway. I gulped. “You mean I’ll have to be there every night?”

“Of course,” said Jule impatiently. “And we’re thinking of having you play part of one of the big ones—Concerto in F or ‘Rhapsody in Blue’—every night. As well as the standards.”

They were serious.

Over the next year, Jule, Sam, and I met occasionally to talk about various musical and dramatic ideas. Then Sam died, having completed only a rough draft of Act One. When Jule called after Sam’s funeral to say that the project had been shelved for the time being, I felt let down. At the same time, though, I couldn’t have been more relieved.

Bobby Brenner’s master plan was working like a charm. In the spring of 1963, I spent three weeks playing a bit part as Angela Lansbury’s young lover in The World of Henry Orient, an offbeat film about two privileged Manhattan schoolgirls who stalk the object of their teenage puppy lust, a hilariously narcissistic concert pianist played by Peter Sellers. I was excited about working with the most brilliant comic actor in the movies, but unfortunately Sellers did not appear in any of my extremely brief scenes, and we never met. The filming at Astoria Studios in Queens was unbearable. George Roy Hill, the director, was a pro, and Angela, my leading lady, couldn’t have been nicer. But I spent most of the time waiting to be called so I could saunter out and recite lines like “Nice weather we’re having.”

The World of Henry Orient opened at Radio City Music Hall to excellent reviews, none of which mentioned me except in passing. It was embarrassing to see my name up there on the marquee with those of Peter Sellers and Angela Lansbury. Worse was the sight of myself in one of my brief scenes, emerging from a shower naked from the waist up and ten times larger than life.

Bobby, who had probably arranged the marquee billing, crowed, “It’s just the beginning, Pete.”

“No, it’s not,” I said. “It’s the end.”

That year, my third album, Peter Duchin at the St Regis, came out. Thanks to all the publicity at the Maisonette, it was a big success, selling several hundred thousand copies. I thought the cover was very cool: a shot of me at the piano in front of the hotel’s belle époque entrance. At 2:30 one morning, we’d taken a baby grand piano out on the sidewalk, where I was photographed playing Gershwin and Porter until dawn to an amazed assortment of night crawlers.

“Forget the movies,” I told Bobby. “This is enough for me.”

Cheray and I had our ups and downs. We had dated on and off, and my feelings had vacillated between seriousness and panic. She was sexy, and I was more comfortable with her than with anybody else I was seeing. She would clearly make some man a great wife. But did I want a wife? Tentatively we discussed marriage, but when the discussions got real, I took off. Finally, Cheray got fed up and married another guy.

Years later, Jackie Onassis recalled something Cheray had told her about our on-again, off-again, on-again courtship. In the spring of 1962, when her hasty marriage was just about over, Cheray had been in the kitchen about to feed her Yorkshire terrier, Toodles, when she spotted a photograph of me in the newspaper under the doggie bowl. “The moment I saw Peter’s face,” she told Jackie, “I burst into tears. Finally, I got up the courage to hear him play in Bridgehampton. He seemed just as thrilled to see me as I was thrilled to see him. That fall we started dating again. Slowly.”

I’ve always liked Jackie’s footnote: “Ari,” she said of her husband Aristotle Onassis, “loved that story. He called you ‘two wonderful children in love.’ When I told him how Cheray had burst into tears, he burst into tears.”

Cheray became something of a regular at the Maisonette—just as my mother had been at the old Central Park Casino thirty years before. Through the fall of 1962 and the following spring, I dated her as well as other girls. I was wondering what to do during my summer break when Geoffrey Gates suggested that the two of us charter a big sailboat and cruise the Greek islands, each with a girlfriend. It sounded pretty darn good to me.

Cheray was my first choice, but I doubted her parents would let her go. She had been brought up so strictly that during her college years she’d been accompanied by her old governess, Miss Fendler, whenever she went for a weekend to a men’s college. But to my delight, her parents caved in, and off we went.

The six weeks on that Greek schooner were the longest period of time I’d ever spent with one woman. To my surprise, I liked it. We sailed from island to island, checking out the ruins. When I suggested celebrating my twenty-sixth birthday with a suckling pig, the captain, Geoffrey, and I went ashore, hired a taxi, and drove to a farmhouse where we bought a poor, squealing pig and loaded it into the trunk of the cab. None of us could watch as the animal was slaughtered on the beach. But after it had been slowly roasted over pine and seaweed, and Cheray and I were holding hands under the Greek stars, I felt a contentment I’d never felt before.

That fall, I was at the bar in the Russian Tea Room, having a Bloody Mary with the writer Terry Southern, when Cheray phoned to give us the news that President Kennedy had been assassinated. Like everything else in New York, the Maisonette was closed until after the president’s funeral, and during the next numbing days, Cheray and I stayed at her parents’ house in Mount Kisco, glued to the television, crying a lot and holding each other.

Inseparable from my feelings for Cheray were my feelings for her parents. In George and Audrey Zauderer, I found a sense of family security I’d previously only known from afar. George was a quiet, serious man of German-Jewish stock who had inherited a small business in real-estate bonds from his father and built it into a sizable fortune through extremely astute investments in commercial properties, mostly hotels. He was meticulous about every aspect of his life. Later, after Cheray and I moved to Westchester County, a couple of miles away from my new in-laws, he never arrived at our place without his gardening clippers, with which he proceeded to prune the deadwood from every bush on our property.

George’s homes on Park Avenue and in Mount Kisco (and later in Jamaica) were opulent—a bit too opulent for my taste—but in spite of his wealth, he remained an extremely modest man. The first thing that comes to mind when I think of George is the little brown paper bag in which he carried his lunch every morning to his office on Fifth Avenue, courtesy of his cook, Margaret.

Audrey Zauderer, who came from a well-to-do Jewish family, was a good deal younger than George—she had been sixteen when they married. She was six feet tall and had an immense mane of blonde hair, and she cut a flamboyant figure. She still does. When she dances by, my band affectionately calls her “the behemoth.”

As much as George loved reading the newspapers for tidbits about New York politics and finance, Audrey devoured the society columns, most of which were written by good friends. She loved entertaining on a grand scale, which she did with originality and obsessive perfection, always removing the plastic that covered the backs of her French antique chairs before “company” arrived. She only wanted the best of everything for her two daughters, Cheray and Pam—and the same for me. Occasionally, George needed Audrey’s nudging to loosen the purse strings, but when he did, it was unconditional. How could I not have loved them?

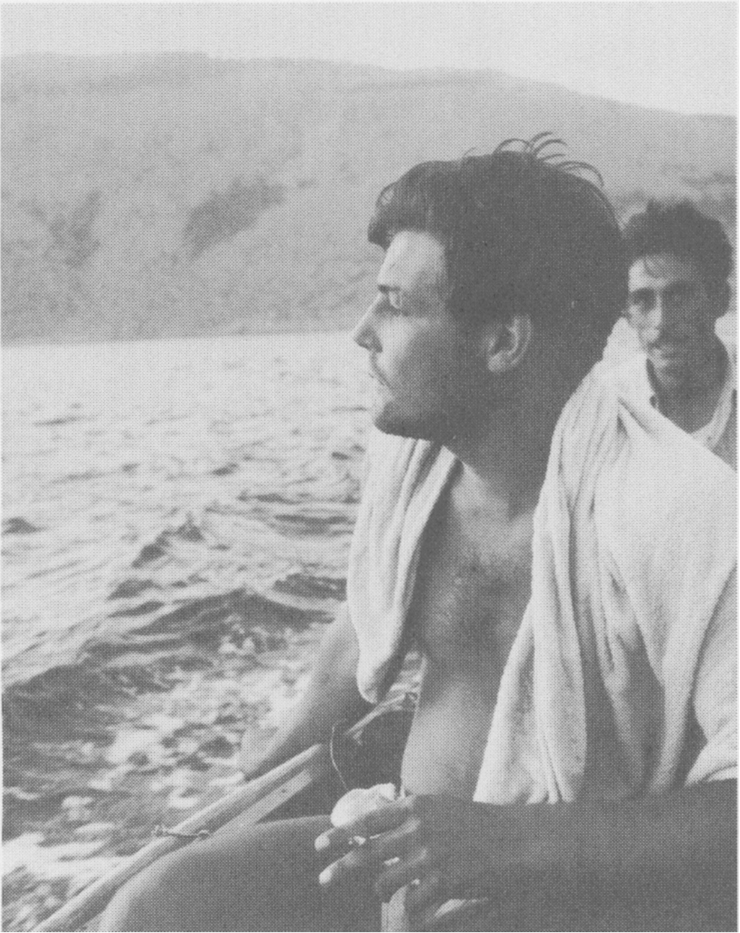

The summer of 1963, I chartered a sailboat with a friend and we cruised the Greek islands for six weeks. Cheray Zauderer came with me. It was the longest period of time I’d spent with one woman.

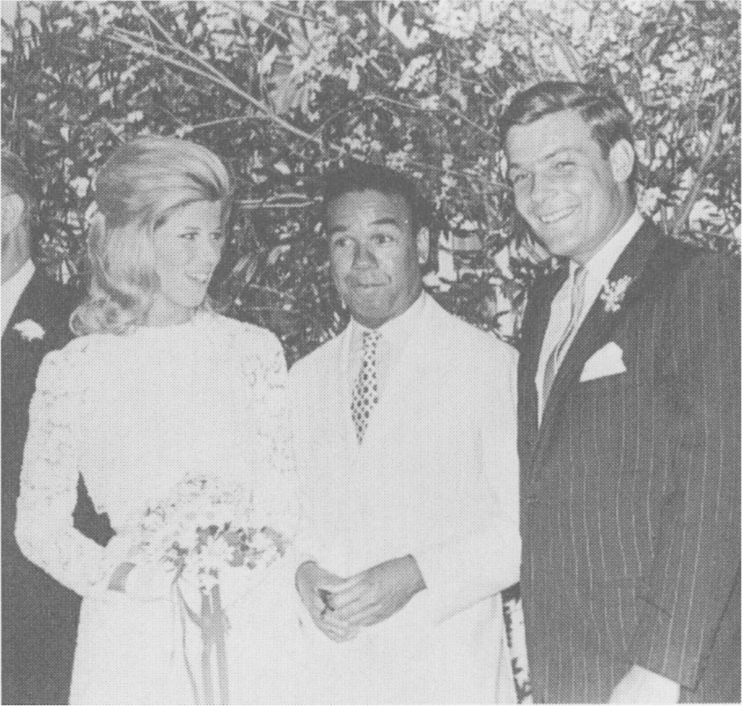

Cheray and I got married on June 24, 1964. My friend Bobby Short was in attendance.

On June 24, 1964, Cheray and I were married in a civil ceremony at the Zauderers’ apartment at 911 Park Avenue. The night before the wedding, Ma and Ave gave the bridal dinner at Eighty-first Street. With a great flourish, Ave produced cases of an ancient premier cru claret that had been brought from the cellars at Arden. The labels were fabulous, the color muddy, the taste beyond vinegar. But Ave was so proud of having “driven it down-state,” as he put it, that not even Ma had the guts to tell him the wine was undrinkable.

George had come to me about the music for the reception. I’m sure he thought I was going to suggest my band. Egged on by Cheray—and backed by Audrey—I’d said, “What about Count Basie?”

Six hundred people came to the reception at the St. Regis Roof, and Basie never sounded better. The last guests left at three in the morning, and I can honestly say it was the best party I never played for.

George and Audrey gave us two wedding presents—a racehorse and a house. One afternoon in Mount Kisco, Cheray and I went over to the farm where George bred horses. “Choose any foal you like,” he said. “I’ll pay the costs until he gets on the track.” Knowing that the chances were a hundred to one that the horse would ever get that far, we wandered among the newborn foals, holding out apples. Of the seven beasts, only one came over and nuzzled us. We picked him on the spot and named him Mr. Right.

“Not the best way to judge horseflesh,” said George.

But Mr. Right couldn’t have been better named. Before being retired to stud, he won a slew of races, among them the Woodward Stakes and the Santa Anita Handicap, thrilling George beyond measure and adding significantly to our family coffers.

The Woodward victory inspired the most personal letter I ever got from Averell. Somehow he found time during his negotiations with the North Vietnamese during the 1968 Paris peace talks to write: “I have been waiting impatiently to get the Sunday newspapers [for] a more detailed account of the race…particularly the stretch run in which Mr. Right held out against Damascus’s drive at the finish. It must have been very exciting.”

For his second wedding present, George had suggested a “reasonable” apartment in the city. We had no idea what that meant, so we picked an apartment on Fifth Avenue in the Sixties. It was in a very Waspy co-op whose board of directors turned us down with the explanation that, because of the other tenants’ concern for privacy, “entertainers” were not acceptable. I had never been turned down for anything in my life, and it came as quite a shock. The real reason, I suspect, had less to do with the board’s distaste for showbiz types—to which Cheray and I hardly conformed—than with the fact that I was half Jewish and she was fully Jewish (though, like me, she had been raised entirely outside the faith). We didn’t make an issue of it. In those days one didn’t.

Cheray and me with Malcolm X in our apartment on East Seventy-first Street in New York.

Instead, we found a wonderful house without a board of directors. A charming four-story brownstone with a garden on East Seventy-first Street, it needed everything from wiring to wallpaper. George, a do-it-yourself sort of guy, snapped it up so he could supervise the renovation. I loved the look of patriarchal satisfaction on his face when the last lightbulb was finally installed behind the mahogany bar in the den.