18

18

THE PRIVATE SPORT

Perhaps because my own mother and father were more shadows than substance, I had never felt a part of another person’s flesh and blood until the birth of my son Jason in 1966. Two years later, my daughter, Courtnay, arrived. She was followed a year and a half after that by Colin, my second son. I thought of the five of us as the fingers of a hand. And I imagined a home that would be like a glove: a place with room for everybody to be independent yet joined.

With children, the house in the city was too cramped, too vertical. Cheray and I dreamed of a place in the country, one with a big playroom where each of the kids would have a corner, a big garden for me to muck around in, and plenty of room for animals. In the summer of 1969, we put our brownstone on the market and headed for the hills of Westchester. We first rented a wonderful old stone house in Bedford Village. Two years later, we acquired from the estate of Cheray’s uncle a derelict house outside the village on forty overgrown acres a couple of miles down a dirt road. We tore down the old house and built a new one—a mélange of Tudor and modern whose main feature was a forty-five-foot-high living room with a big stone fireplace surrounded by a wall of glass and a sweeping view of woods and meadow.

Because my father had died when he was only forty-one, I’d always been haunted by the feeling that I might not live past my forty-first year, and I was determined to do as many things as possible with my kids before then.

I taught them every sport I knew, throwing baseballs and footballs, kicking soccer balls around the lawn, lobbing tennis balls. I taught them how to swim and how to ride their first bikes. I took them to school on a motorcycle, just as Harry Whitney had taken me. I read them my favorite bedtime books—The Jungle Book and Babar stories. I insisted they all take piano lessons, but I was afraid that if I pushed them, they’d get turned off. Instead, to my great regret, they never got turned on.

Together, we went to museums, concerts, plays, and the ballet, to dude ranches in Montana so they could learn how to ride Western style, to game parks in East Africa so they could see great wildlife outside a zoo. I taught my kids how to shoot—first BB guns, then .22s, then shotguns. Most important of all, I taught them how to fish.

Cheray had put up no argument when I suggested we take our honeymoon in the wilds of Quebec. We spent the first couple of weeks fixing up a log cabin on a remote lake, a three-hour drive west of Montreal. It was situated on a hundred acres of woods that I’d bought some years before at the suggestion of Donald and Jean Stralem, who owned an enormous property next door. As a wedding present, Donald and Jean had given us plumbing and electricity. Cheray and I furnished the cabin with primitive, local furniture and an old upright from the Zauderers’ house in Mount Kisco. With me at the helm of a borrowed tractor, we made a clearing for a front lawn.

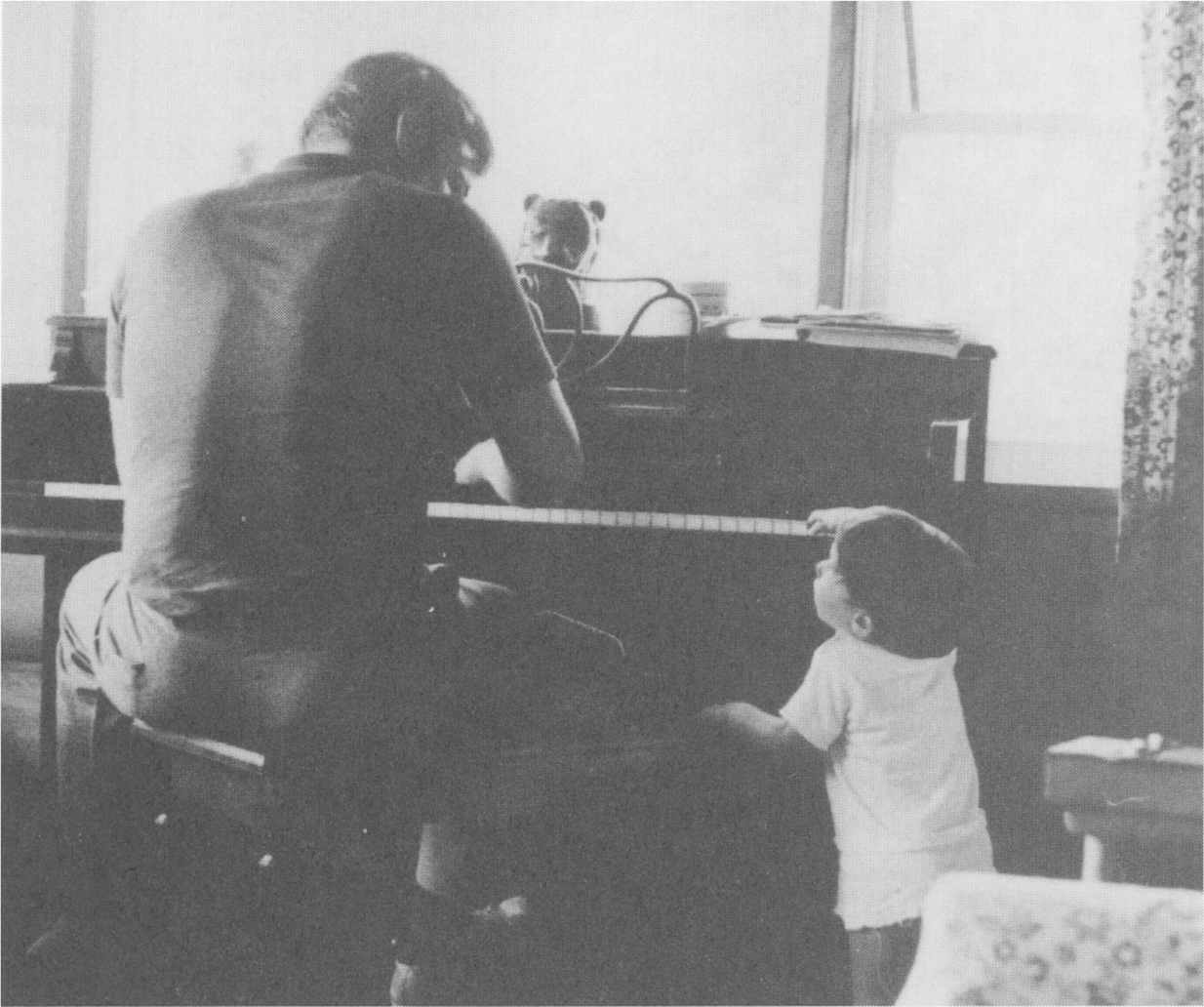

Me and my oldest child, Jason, in our cabin in the Canadian woods.

To my delight, Cheray loved the isolation and simplicity. She wasn’t much interested in fishing in Limmer Lake, but she didn’t complain when I disappeared for hours in a rowboat—the same kind of boat I’d had at Arden.

When friends of ours called and suggested we join them for some serious fishing in the northernmost part of Quebec, I was worried that ten days of camping out in a corrugated tin shack, sleeping on wooden bunks in bedrolls, would be asking too much of my bride from 911 Park Avenue. But Cheray said, “Let’s go.”

The creature comforts were zero, the fishing terrific. We waded in fast water in near-impossible footing. We fished in deeper water from perilously tippy canoes. Because the fish hadn’t been spoiled by invaders like us, they gobbled up everything we threw at them, It was instant gratification. I tried to teach Cheray how to cast, but she was happier just sitting in the canoe, walking along the shore, or immersing herself in a good book.

Instant gratification is not what fishing is all about. The first thing fishing does is make you slow down—way down. You can’t be any good at it unless you stop everything and begin to look, really look—whether it’s for terns diving into a stretch of the Gulf Stream (a sure sign of fish below) or that dimple on a slick glacial lake (sure sign of a hungry trout).

Cheray and I built a house in Westchester where we could raise the kids and let the animals run around.

Slowing down used to come easier, when I was a child at Arden and going fishing was simply part of everyday life. Now, making the transition from bandleader and husband to fisherman requires some effort.

Bill Kitchen taught me everything about the rituals of preparation: first, unscrewing the fly rod case; then, sliding the rod from its cotton sleeve, fitting the parts together, attaching the reel, stringing a line through the guides, deciding on the leader, finally attaching it to the end of the line, either by knotting it to the existing tippet or by tying it to the loop left from the previous outing.

All fishermen know the charge of adrenaline that comes as you approach the water. But the best ones also know to rein themselves in for ten or fifteen minutes. Very quietly, they sit down out of sight in order to read the situation: the flow of the current; the play and hatch of insects; the position of the sun, which is crucial, because you don’t want to spook the fish with your shadow; any perceptible movement of fish. Only when he’s taken it all in and thought about it does the good fisherman feel ready to select the fly and wade in.

There’s a story about the legendary fisherman and author the late Lee Wulff, with whom I was lucky enough to fish on many occasions. At an old Canadian salmon camp on the Upsalquich River, the houses were situated on a hill overlooking the “home pool,” a hundred-foot stretch of water in which, sitting on the porch, you could actually make out the resting salmon. It was August. Hot and dry. Low water. And none of the fishermen had been able to move even one of the fifteen or more visible fish.

Lee arrived for a couple of days of fishing. They bet him he couldn’t catch anything either. “Lee, those damn fish haven’t shown any interest in anything we’ve thrown them,” said one of the guys. “John here was talking about using a harpoon. And we’ve almost run out of bourbon.”

Lee sat down on the porch and for about an hour did nothing but look at that pool of fish. Finally, he put together his rod, slipped down the hill, and proceeded to catch—and release—every last salmon. Lee was so meticulous in his scrutiny that once, when the two of us were filming a show for The American Sportsman series on the Lairdahl River in Norway, I watched him tie a new fly right on the spot because none of the ones we’d brought had worked.

Like all great fishermen, Lee had a respect for nature that was at once romantic, philosophical, and scientific. How different the sport has become in the last twenty years. These days, everybody who has a little money seems to want to fish. They have to have the latest and newest equipment. They have to spend outrageous sums renting fishing space on the most exotic, faraway rivers—just to say they’ve been there. They have to build, buy, or hire boats with the latest electronic fish-finding devices—gizmos that take much of the chance out of the sport. They have to compete, as if they’re still in the bond market. Thirty-five years ago, when I started tarpon fishing in the Florida Keys, you rarely saw another boat. Silently you poled the flats in solitude. Today it’s a traffic jam.

As far as I’m concerned, fishing has nothing to do with competition. It’s the most private and personal of sports, and it elevates you to heightened levels of consciousness. Fishing is one of the few sports that can be as pleasurable by yourself as in the company of friends. But they have to be the right friends. Fishing can bring out the worst in people who, in other settings, are above reproach. Suddenly that urbane landscape architect becomes ferociously territorial about his pool in the stream. That mild-mannered author of musical tomes becomes a loudmouth braggart. That gray, pin-striped banker, famous for his probity, reveals himself to be a terrible liar, adding pounds and inches to the bass that never was.

A few years ago, my best fishing buddy, the art critic Robert Hughes, and I went to the South Island of New Zealand for giant brown trout. With us was an aristocratic Brit whose company I’d enjoyed for many years. The moment the Brit put on his waders, he underwent a complete personality change, becoming rude, sullen, and standoffish. Perhaps because Bob is Australian and I’m American—and our friend was temporarily not the lord of the manor—he’d lost his bearings. Or perhaps he just wasn’t up to the delicate camaraderie that prevails among real fishing buddies.

The kind of fishing I enjoy demands thoughtfulness and good manners. They’re not the sort of manners that are dictated by a country club—there’s no dress code among fishermen. It’s simply a way of behaving that starts out as respect for nature and becomes respect for one another.

Fishing gives you its own time and space. I’ve surf-cast for blue-fish off a Florida beach, five feet away from Ave. I’ve shared ten miles of a Colorado river with nine others, each of us standing a mile apart from the next, all day long from breakfast to supper. I’ve done a television show on the White River in Arkansas (pre-Clintons) with the cameras rolling just inches from my shoulder. I’ve been dropped into a far corner of Alaska by floatplane and left alone for the day with nobody but grizzlies and a guide. I once fished on a stream twenty yards from the Long Island Expressway at the height of the evening rush hour, and I didn’t hear a single car.

No matter how different the circumstances are, time disappears when you’re fishing, and as the hours pass by unnoticed, it becomes unbearable to think of quitting, even to think. The shadows grow long, and you’re carried along by the sound of the stream, the repetition of casting, the intensity of focus.

Wives and nonfishermen always ask me the same question: What in God’s name do you all do when you’re not fishing?

When I sink into the ritual of fishing, everything else fades away.

Quail hunting in Georgia.

There are only a few things that are really essential in a fishing camp: a hearty breakfast; a lemon, some salt and pepper, a can of shortening, a box of matches, and a roll of aluminum foil; a well-stocked bar to come home to; a good supper; and a place to sleep—preferably dry. Conversation is a bonus. There’s something about having spent the day alone, walking up and down a piece of water, that frees the tongue to talk about everything under the sun. You don’t gossip. You don’t feel compelled to confess. Fishing takes your mind to more abstract places. You may be a half dozen guys from different backgrounds, but you find yourselves trying out ideas about the things that really interest you—politics, art, music, history, sports. When anybody brings up something to do with business, I tune out and open a book. I’ve done some of my best reading in fishing camps. The mind has slowed down.

My favorite fishing spot is on the Whale River in northern Quebec. To get there, you fly to Montreal, spend the night, and the next morning pick up the once-a-day flight to Kuujjuaq, an Eskimo village. There you catch a floatplane for the hour’s flight to the Whale, cruising low over tundra streaked with caribou trails. The only worry is that you’ll miss the return plane to Montreal and have to spend the night in Kuujjuaq, God knows where.

The camp I stay in can fish ten rods comfortably. A good part of its attraction is that most of the fishing can be done by wading or standing onshore, rather than from a boat. Apart from the fish and other fishermen, the only creatures you encounter are gulls, hawks, ospreys, and a real weirdo—the crossbill sparrow. You might see caribou, ambling through the woods or swimming across the stream in their perpetual migration. You might spot a bear, in which case you stay very still. The weather is eccentric. It can be hot enough during the day to fish in a T-shirt. At night you’ll probably need a blanket over your sleeping bag. On my most recent trip to the Whale, I was getting in some last-minute fishing while waiting for the floatplane to fly me to Kuujjuaq, from where I’d embark for Montreal, thence to Detroit, and finally to Kansas City, where I was to play a wedding that night. At eight in the morning, what had been a perfect late August day with temperatures in the sixties suddenly turned into December: A blizzard was followed by a hailstorm with stones the size of jelly beans. An hour of this, and suddenly it was summer again. In came the plane, just in time for me to make my connections. Eight hours later, I was under the tent in Kansas City, strapped into my black tie.

It was on the Whale that I had my greatest day of salmon fishing. It was a cold, slate gray afternoon, with a brisk, northern wind blowing upriver. Perhaps two hours of good fishing light remained before sundown. The night before, one of the fishermen had recommended a pool called “the Ledge.” “The water level should be just about right for holding some fish if a run starts coming,” he’d said. “It’s just beyond a big rocky point. You can’t miss it.”

I wasn’t having any luck where I was when I remembered that rocky point—about a quarter of a mile upstream. I made my way to it along the shore, moving crabwise so as not to spook any fish that might be holding near the bank. When I reached the point, I sat down on a rock to look and dropped the fly just over the water’s edge to get it out of the way. While the fly idly bobbed in the stream, I sank into that state of oneness that I can achieve only by being near water or listening to Bach.

God knows where my mind was when a salmon, very large, leapt out of the water, dive-bombed my fly, grabbed it in his mouth, and took off. I got hold of the rod just before it would have vanished with the fish, jumped up, and for the next fifteen minutes played him—a bright, silver male that had just come into the river from Ungava Bay. I landed him, released him, and wondered whether there were any more where he’d come from.

Over the next hour and a half, I cast exactly eleven times and hooked a fish every time. I didn’t have to walk more than ten yards. I barely got my waders wet. Finally, only because the guide in his motor canoe had arrived and it was getting quite dark did I realize that it was time to quit. Dead tired as I was hobbling into the boat, I’ve never been so exhilarated. Each fish had presented me with a different challenge. With each landing and release, I’d gone to another plateau of satisfaction. All were bright, strong fish—none less than fifteen pounds. I kept only the last one for supper.

The guide, a son of the camp’s owner, said, “How’d you do?”

“There’s a brand-new run in the river,” I replied.

“It’ll be good tomorrow then,” he said.

That was all there was to say.

One of my favorite fishing buddies doesn’t fish. Driving to my house in Connecticut, I often stop by the only store I enjoy shopping in. (Virtually every other store I’ve ever been in puts me into a cold sweat.) Harry Whitman has owned The Bedford Sportsman, right across from the railroad station in Bedford Hills, at least since Cheray and I moved out to Westchester. Harry sells everything from flies, rods, waders, and vests to sporting prints and sporting books, old and new. He’s even been known to sell a few of the latest compact discs of me and the band. Everything at Harry’s is top quality and in seeming disarray—the way a store should be.

Harry sits behind the counter, directly in front of the door—a tall, fair man with reddish hair and a beatific smile, I’m not sure that Harry has ever held a rod except to sell it, but his appreciation of the sport is as deep as that of any fisherman I know. Harry sees fishing as having a great tradition. He knows that every pool, whether it’s on the Housatonic or the Lairdahl, contains a thousand stories. Without any stories of his own to tell, he draws to his shop all the best fishermen from a hundred miles around. Like me, they come to buy flies and leaders, or perhaps a magnifying glass and hook sharpener—stuff they’ll never use. Or to chew the fat about where they’re going fishing next. Or to leaf through first editions of magnificently written fishing books by Norman Maclean, Joe Brooks, and William J. Schaldach. Or simply, as Red Smith put it, to “tackle-fondle.”

Ma