19

19

LOSING MA

It was Otto who called with the news: “It’s bad, Peter,” he said over the phone. “Marie died last night of a heart attack. You’d better get on the next plane.”

It was September 26, 1970, and we were far away. For three days, Cheray and I had been guests of my friend Simon Frazier, the eighteenth Lord Lovatt, at Beauly, his Scottish castle near Inverness. We’d come over for two weeks of stalking stag and fishing for salmon. We’d visited the nearby loch, where Nessie the monster was reputed to reside. We’d begun to unwind.

I took the call in the library, an immense paneled room hung with eighteenth-century French tapestries bordered with fleurs-de-lis. After Otto hung up, my eyes filled with tears. Mindlessly I began counting the fleurs-de-lis. As they got blurrier, I just stood there, holding the dead phone, counting.

Finally, Cheray came in. Giving her the news, I totally lost it. I sank to the floor, turned on my side, grabbed my knees, and rocked slowly back and forth, as I had done as a child when I couldn’t get to sleep.

The next day we flew to Washington. Ave was beside himself. Marie had died at sixty-seven. He was seventy-nine and had never expected to outlive her. Immediately he wanted to show us her body. In his Checker town car with its awful springs, we bounced up Massachusetts Avenue to Joseph Gawlor’s funeral home. As we entered the dim room where Ma was laid out in an open coffin, I couldn’t bear to look. Ave, clutching my arm heavily, said, “Isn’t she beautiful! Isn’t she beautiful!”

That night we joined the family at the house in Georgetown for dinner, along with Mike Forrestal. While Mike and I planned the funeral music, the others manned the phones. Just before bed, Ave asked Cheray and me to drive him back to Gawlor’s. He had something on his mind.

The place was locked up for the night, but after much ringing of the bell, we were let in by a watchman. This time I forced myself to look. Ma was dressed in one of her favorite dresses, but she had on much too much makeup. There were no dark glasses. No Viceroy in a white plastic holder. This woman belonged in Madame Tussaud’s. She was a cartoon of Ma.

The sense of loss I felt was physical, as though I were suddenly without a vital organ. Ma had been my best sounding board, my late-night drinking buddy, my bulwark, my conscience. Definitely my last resort. From the beginning she’d watched over me. She’d been in the driveway at Arden when Chissie and I had returned from California. She’d been the life of the party at my graduations, openings, and personal celebrations. She’d stood in the receiving line at my wedding.

During the birth of my first son, she and Ave had come to New York Hospital with sandwiches and vodka and kept an all-night vigil on folding chairs in the corridor. She had always said, “Oh, Averell, why don’t we take Peter along?” Late one evening, just a few months ago, the two of us had been sitting around her living room in Sands Point. After too many nightcaps, I had made her cry with my angry outburst: “Why didn’t you marry my father? You loved him, didn’t you?”

Suddenly Ave bent over the coffin. I thought he was going to kiss her. Instead he said, turning to Cheray, “I want her wedding ring. Can you help me get it off?” Cheray gulped, but she raised Ma’s left hand and slipped off the ring, one of the many she always wore. Cheray handed it to Ave, who put it in his pocket.

“Let’s go now,” he said.

I thought he was keeping the ring for himself. But a few days later, at the reception after the funeral, he gave it to Ethel Kennedy. In recent years, Ethel had become one of Marie’s best friends, just as Ave had become one of Bobby’s before the assassination in 1968. Even so, I was shocked by the gesture. If Ave had wanted to give Ma’s ring to somebody, it should have gone to her own daughter, Nancy.

Ethel herself was flabbergasted and at first didn’t want to accept it. Recently, when I asked why she had, she replied that she hadn’t wanted to offend Ave. “I still wear it,” she added. “And I think of Marie every day.”

Of Ma’s two longest obituaries—one in The New York Times, the other in The Washington Post—I preferred the latter. Whereas the subhead in the Times cast her strictly as Ave’s helpmate (“Humor and Hospitality Aided Husband in His Numerous Government Assignments”), the Post’s line was all about her: “Art Dealer, Hostess, Witty Grande Dame.” I liked it that the obituary cited one of her typical acts of generosity: the time, after JFK’s assassination, when she’d given her Washington house to Jackie Kennedy and her two children without a second thought. (The Post didn’t mention the diplomatic skill she had employed getting Ave to move into a room in the Georgetown Inn for several weeks. As Ma had joked over the phone, “All he does is complain about the goddamn bath being too short!”)

Both newspapers misquoted the one-liner she’d thrown at Ave during a particularly dicey stretch of Franco-American diplomacy: “For gosh sakes, Ave, de Gaulle doesn’t know his arm from his elbow.” How I would have loved hearing her correction of that. Ma had never said “gosh” in her life, and I know she didn’t say “arm.”

There were two memorial services. The first, in Washington’s National Cathedral, was filled with friends from all over, high and low. Marie had commanded extraordinary affection from anyone who had ever worked for her, and I spotted not only all of her own servants, including a few part-timers, but those of her friends, whom she had always greeted like pals.

The second service was held in St. John’s, the little Harriman chapel at Arden. It was mostly just family, with the addition of Bob Silvers and George Plimpton, who had taken as much delight in Ma as she had in them. After the service, Ma was buried in a wooded knoll near the chapel in the Harriman family plot, next to Averell’s parents and his sister Mary. A space was left on the other side of her grave for Averell.

I received more than a hundred condolence letters, written to me as though I had been Ma’s son. And the truth is, I felt I had lost a mother.

After the thousand thank-you notes had been written and the parade of condolence callers was over, Ave went into a deep depression. Even though friends continued to look in on him, he didn’t cheer up. I don’t think he’d realized how dependent he had become on Marie during the previous ten years.

That winter, he went down to Hobe Sound and rarely went out. When Cheray and I called to ask how he was doing, he plaintively asked whether we might come down for a visit. “How about our spending a few months after New Year’s?” I suggested. There was a long pause—possibly to turn up his hearing aid. Then: “Fine, Petey. Come along.” It was Ave’s way of saying, “I’d love it.”

In January, Cheray and I flew down with the kids, the nurse, and Malcolm X to Hobe Sound, where temporary places were found for Jason and Courtnay in the local school. Ave was in worse shape than we’d imagined. He had mastered every sport from polo and croquet to bridge. He had served in more high-level diplomatic jobs than any American statesman since John Quincy Adams. He had matched wits with many of the century’s most ruthless leaders, from Stalin to Marshal Tito. Now he was like a helpless child. He was so listless that he could barely watch the evening news.

He talked incessantly about Marie, reminiscing about the trips they’d taken together and the wisecracks of hers that had made him laugh—more now than when she’d said them. He loved telling about the time in Tehran when he’d been sent by Truman to settle the crisis over Mosaddeq’s seizure of the British oil concessions. One evening when Ave was off somewhere else, Ma had paid a call on the prime minister. Along with other dignitaries, she was led into his private chambers. There, the father of modern Iran lay in bed, seemingly indisposed. Finally, everyone was dismissed except Ma. Diplomatically, she inquired about the prime minister’s health, whereupon he leapt out of bed on his birdlike legs and lunged at her. This set off a mad chase through the Persian gardens, Mosaddeq in his red silk pajamas, Ma clicking along in her high heels. The detail Ave loved best was the pajamas.

Ma and Ave in their living room in New York, with Picasso’s Woman with a Fan over the couch.

Cheray and I knew he was getting his old self back when he burst into our room one day. “Petey,” he said, “I’ve got something I think you’ll find amusing. I’ve just been going through some of Marie’s old things, and look what I found.”

It was a tattered photograph of me at the age of two, sitting on the potty with my pants down, smiling as always at the camera. Across the lower half, stuck into the cheap plastic frame, was a torn-off piece of Ave’s private stationery with a message scrawled in his own messy hand: “For Peter, With love—for letting me win occasionally at croquet. Ave.” Coming from Ave, the gift was astonishing, especially the fact that he’d assembled it entirely with his own hands.

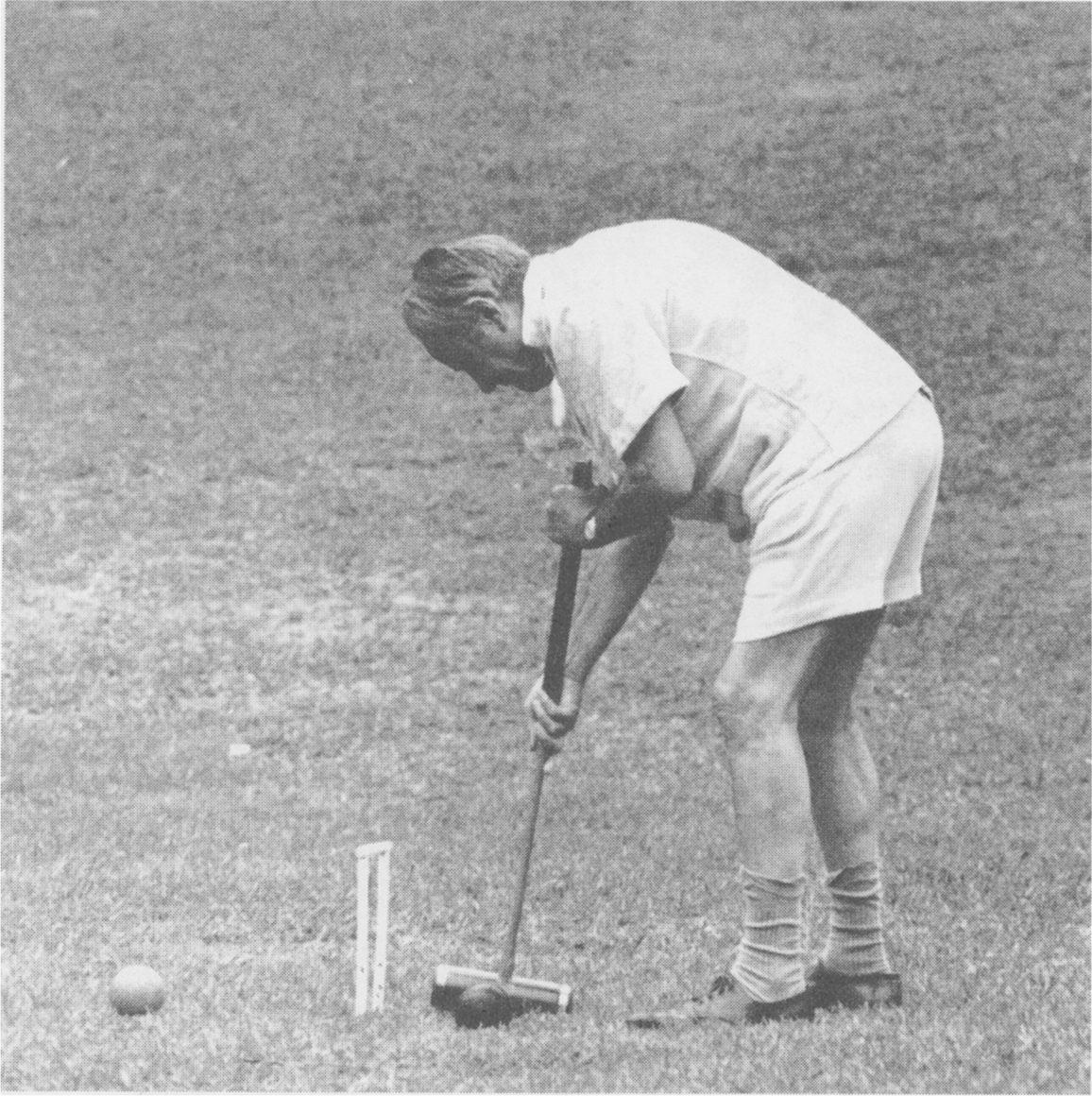

This turned out to be a happy time. Between taking off for one-night jobs with the band, I read a lot, played croquet a lot, fished a lot, and learned how to fly a plane. Not since our horse-and-buggy rides had I felt so relaxed with Ave. We played croquet every afternoon—for Ave, the best therapy in the world. I guess there’s nothing like hating to lose to make you feel young again.

One morning at breakfast, he said, “Pete, I’ve been thinking. I can cut off an acre down by the grapefruit grove without hurting the property. I’d love to give it to you and Cheray if you’d consider building a small house on it. It’s right on the ocean. Something you and the kids could use from time to time. You know, there will soon be no beachfront property left on the Atlantic coast.”

This was more surprising than the photograph. The one subject that nobody—not even Ave’s wife or children—had ever been brave enough to bring up with him was anything to do with money or property Ma had loved going shopping with Cheray, who couldn’t get over how timid she was about charging purchases to Ave. One day, long after one of Ma’s fur coats had reached a stage beyond repair, they found the perfect replacement at Bergdorf’s, a mink for $5,000. As Cheray later told me, “Marie was just terrified. It took everything I had to give her the courage to buy the damn thing and have the bill sent to Averell.”

After Ma died, Cheray and I moved down to Hobe Sound to help Ave through a bad time. Playing croquet was one of the only things he enjoyed.

I had always been thrilled to be considered “family” by the Harrimans, but it was a matter of pride for me never to ask Ave for anything. About a year before Ma died, she’d mentioned she wanted to leave me a Degas sculpture in her will, one of the bronze ballerinas with a real tutu. Ave had jumped in and said, “Oh God no, Marie. It’s worth far too much. Can’t you think of something else?” (Fifteen years later, after Ave died, his widow, Pamela, sold the Degas for several million dollars.) Ma had next suggested leaving me her best Daumier bronze. Again Ave had vetoed it for the same reason. What she did leave me was $5,000 and a small Daumier bronze called Le Fat Sebastian. The caricature of a self-satisfied Parisian businessman, circa 1860, still sits on my desk in New York, where it always gives me a chuckle. I’d never dreamed I would be named in any Harriman will, and I was thrilled by Ma’s generosity. But I do wish Ave had kept his mouth shut about the Degas.

Now, lonely as he was, Ave was offering me an acre of Hobe Sound oceanfront, a valuable chunk of his property. “Great,” I said, “we’d love it. But are you sure?”

“Of course I am,” he said. “Let’s go walk it.”

When Ave suggested that we call up an architect, I knew he was serious. He took great pleasure going over the sketches for the modest bungalow we envisioned, offering many suggestions. Thinking I might actually own a piece of this childhood place, I felt a wonderful sense of roots. The fact that I would also be providing Ave company—as well as a built-in croquet partner—in his old age made it even better.

Since the kids would want to use the Jupiter Island Club, I called on Nat Reed and his mother, Permelia, just to make sure there wouldn’t be a problem over membership. “Don’t be silly,” said Nat. “This is your home. The moment you build your house, you’re in.” A week later, I got a letter confirming it.