Black bean sauce or paste is a Chinese condiment made from fermented black beans, used in cooking and in marinades. Some varieties are flavored with chiles and/or garlic. Make sure there is no MSG (monosodium glutamate) or shrimp paste in whichever black bean sauce you choose, as many people are allergic to these additives. For garlic-flavored black bean sauce, we use the Lan Chi brand.

There are many brands of chile-garlic sauce or paste available, each with its own heat level and flavor. We use the Heavenly Chef Vietnamese Garlic Sauce.

Hoisin sauce is a thick, sweetish soybean-based Chinese condiment commonly used in marinades, or as a dipping sauce. I use it a lot in marinades for duck, pork, quail, and squab. I’ve heard it referred to as Chinese barbecue sauce.

Most soy sauces are made with soy beans plus wheat (in some cases as much as 40 percent to 50 percent wheat) and salt. There are two classic kinds of soy sauce—light and dark. Dark soys are often colored with caramel or molasses, and are less salty than light soys. Dark soy sauce is usually used in cooking, whereas the saltier light soy is generally used as a dipping sauce. Note: when I say “light” soy, I do not mean the reduced-salt “lite” soy sauces you may see in the market. I do not recommend these at all. There is also a mushroom soy sauce, which is flavored with essence of straw mushrooms. It is good in marinades and for use as a dipping sauce. (See also tamari and ketjap manis, below.)

Tamari is a thick, dark Japanese soy sauce with a very low wheat content. Some brands are made by very strict traditional methods, and you can even get some Japanese tamaris that are 100 percent soybean. These special tamaris can be very pricey.

Another type of soy sauce is ketjap manis (also kecap manis) from Indonesia—dark brown and syrupy, it’s much thicker and sweeter than Chinese soy sauce. A decent substitute for it would be a mix of two parts tamari to one part molasses.

Kaffir lime leaves are very aromatic and, when cut, give off a little essential oil that adds a nice background flavor and aroma. There’s a tiny bitterness to them that cuts the richness of a dish in just the right way. Fresh kaffir lime leaves may be difficult to find, but many Asian markets carry frozen leaves. It’s worth a little legwork to find the real thing, but if you can’t, it’s okay to substitute a little lime or lemon zest. The fruit itself is a hard little warty thing that you don’t actually get much juice out of. They are probably used by somebody for something, but I don’t know what that might be.

Lemongrass is a Southeast Asian herb that looks like a dried-up foot-long reed or overgrown scallion. Peel away the tough outer stalks until you get to the smooth, pale yellow inner stalks. This bulblike part can be minced up and added to stir-fries, marinades, sauces, soups, and more. Lemongrass has a very delicate lemon flavor but is not at all sour.

The next-best thing to baking your own breads is to seek out local bakeries that make what I call “artisanal,” “rustic,” “country,” or “levain-style” breads. By this I mean bread with a great crust and an airy but structurally sound crumb, the kind that makes crispy toast that won’t turn soggy immediately when topped with something saucy, yet will not cut you up when you bite into it.

Good bread can’t be made by shortcut methods. Artisanal breads require slow, low-temperature rises of the dough (as much as fifteen hours). There are many bakeries around now that make these great European-style breads, some with rye and whole wheat flours in varying ratios to white flour, resulting in loaves with excellent texture and structure. In Northern California, there is the Acme Bakery, a company that was a leader in the artisanal bread revolution. Acme supplies many of the restaurants in this area, and its breads are sold in many of the local markets. In New York City there is Amy’s Bread, which has several shops. Just do a little exploring wherever you live. Check out the smaller bakeries, too, as you never know. Della Fratoria in our area does breads in a wood-fired oven. Its sesame seed–olive loaf is one of my all-time favorites.

To make toasts (also known as bruschetta), brush both sides of the bread with olive oil and place on a baking sheet. Bake in a 375°F oven until the bread begins to turn golden, and is crispy on the outside but still a little soft in the middle. If you already have the grill going, you could toast the bread on the grill. You can also pop the slices in a traditional toaster and coat them with olive oil or butter as soon as they come out (do it while they’re still hot).

You can make croutons any size or shape you like. It all depends on what you’re serving. Sometimes I garnish soups with tiny croutons, cut into quarter-inch dice or smaller; for finger foods, I like two-bite-size toasts. For diced croutons, toss with a little olive oil and spread out on a baking sheet. Bake in a 350°F oven for five to ten minutes, until golden brown and crisp through. Stir once or twice to ensure even cooking. For flat croutons, brush with olive oil and bake until toasty and crispy all through.

A true levain is a sourdough starter made from wild yeasts. A levain-style bread may not have a wild yeast starter but is made by the older, slower methods of breadmaking that a levain requires.

A bâtard is a one-pound loaf of sourdough French bread.

I use a lot of chiles and peppers in my cooking, even now that Miramonte has been transformed into Cindy’s Backstreet Kitchen. Both Latin and Asian markets carry an amazing variety of fresh and dried chiles, and local farmers’ markets are a good source, too.

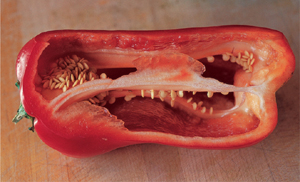

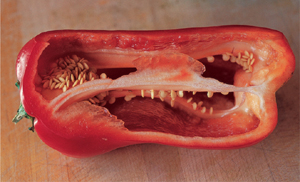

In general, the smallest chiles are the hottest ones of all. The little Thai bird chiles, for instance, can take your head off. Much of the heat of a chile is held in its seeds, so if you want a less spicy result, remove the seeds as part of the chile preparation. Be sure to wash your hands thoroughly after handling chiles, and do not rub your eyes.

Roasting and peeling fresh chiles and peppers. Place the chiles or peppers over an open flame on a gas stove or a grill, or place them in a heavy flat skillet over an electric element. Turn them as needed to char and blister the skins evenly. When the skins are nicely blackened all over, put the chiles in a plastic bag or a large bowl. Seal the bag or cover the bowl, and allow the chiles to cool. Once they are cool, the skin should slip off easily.

Toasting and rehydrating dried chiles. I always toast dried chiles before using them, as this brings out their flavor. You can toast chiles in a number of ways. Start off by stemming and seeding them, then place the chiles on a baking sheet and put them in a 375°F oven for two to three minutes, until aromatic; or, using tongs, hold the chiles over a direct flame for about a minute, turning as you toast; or toss the chiles around in a skillet over medium-high heat for one or two minutes. The main point is to warm them enough to release their oils and to soften them up a little. You’ll know when you’ve accomplished this by the aroma they give off. Be careful not to toast them too long, as they will become bitter.

To rehydrate dried chiles, soak them in warm water to cover for ten to fifteen minutes, until they are soft. Sometimes I weight the chiles down with a saucer to make sure they are completely submerged.

A note on piquillo peppers: Once I discovered these sweet, richly flavored pimiento-style Spanish peppers, I was hooked. I even began inventing recipes for them. Piquillos are smallish red peppers, about two inches long and one inch across at the top, tapering to a little hook at the bottom. (In Spanish, piquillo means “little beak.”) Fresh piquillos are not currently available in the United States, but you can find cans or jars of them at specialty foods stores, or get them through a mail-order source such as The Spanish Table. They are fire-roasted and peeled and come ready to stuff, slice, or puree.

Epazote is a spiky-leafed green herb frequently used in Mexican cooking. It is pungent and a little bitter. Some say it tastes like musty mint or basil. Once you get used to it, you become addicted. It is always used in cooking black beans, maybe because it is said to have antiflatulent properties. It will grow like a weed in a less-than-perfect environment. Only use fresh epazote, as the dried is like sawdust. If you can’t find epazote, use some Mexican oregano and mint or basil instead. It won’t be the same, but it should be delicious anyway.

My favorite type of salt is Maldon sea salt from England, made by a special process that involves boiling seawater. The salt comes in the form of delicate pyramid-shaped flake crystals (they remind me of snowflakes). It is most often used as a finishing salt, but I use it in cooking as well. Try crumbling a little over grilled fish or meats just before serving. It adds a little crunch but is not overly salty. One of my greatest pleasures is to eat lunch in my garden, munching on tomatoes right off the vine, with a kitchen towel on my lap and a box of Maldon salt by my side.

To really boost the flavors of nuts, toast them briefly before using them. Preheat the oven to 350°F, spread the nuts out on a baking sheet, and toast until lightly browned.

For the oyster recipes in this book I recommend using live in-the-shell oysters only. To shuck an oyster, wrap the hand that’s going to hold the oyster in a thick towel or wear a glove; using the other hand, place the tip of an oyster knife in the hinge at the back of the oyster shell, and work the knife side to side until you feel or hear a pop. Slide the knife along the deeper bottom shell to cut the muscle that attaches the oyster to the shell. Be careful not to cut through the oyster itself. When your meal is over, toss the oyster shells in the compost—pure calcium.

Because it is made strictly with smoked Spanish pimientos, pimentón (Spanish) paprika tastes quite different from Hungarian paprika. The two can be used interchangeably, but when I make Spanish dishes, I go for authenticity (unless I’m stuck). In a pinch, I’ve mixed a little ground chipotle (smoked dried jalapeños) with Hungarian paprika to a get a touch of smokiness. There are three types of pimentón: sweet and mild (it may be labeled pimentón de la Vera, dulce, or simply dulce), bittersweet medium-hot (agridulce), and hot (picante). La Chinata and Chiquilín are the two brands most commonly sold by specialty stores and mail-order firms.

There aren’t any stand-alone green salads in this book, but I use various combinations of greens tossed with different light vinaigrettes to add a finishing touch to many of the plates. Each of these mini salads is designed to complement, highlight, or balance the flavors in a particular dish, and to make it attractive as well.

If you’re willing to experiment, there are many different kinds of greens available in the markets, especially at farmers’ markets; or try growing your own. I am partial to arugula (also known as rucola or rocket). My latest fad is growing “wild” rucola, which is a slower-growing, more pungent variety with a sturdy but not tough texture and beautiful spiky dark green leaves. I’m not sure why wild rucola is more expensive in the markets, because it grows like a weed in my garden, reseeding itself and popping up all over.

Always give your greens a thorough rinse in cold water, and dry them in a salad spinner or in towels. Greens should never be dressed until just before serving, so if you’re not going to use them right away, store them in the refrigerator in plastic bags, or in a bowl covered with a damp towel.

Before cooking sea scallops, check them over to see if there is a tiny white ligament attached to them on one side. This “little hard knobblies bit,” as Jane Grigson called it in her great Fish Book, is what connects the scallop to its shell. It is tougher than shoe leather, and should be removed. Pull it off gently so you don’t tear the scallop apart. If you can’t find it, your fish purveyor has already taken care of it for you.

To toast seeds, heat a small dry skillet over medium-high heat. Pour in the seeds and cook till they are aromatic and lightly browned, stirring or shaking them continuously. Keep a close eye on them, as they can go from perfect to burned all at once. Remove from the hot pan as soon as they reach the desired doneness.

You can often find squash blossoms in Latin American, Mexican, or Italian markets, and at farmers’ markets, too. Or plant a bunch of zucchini and harvest your own flowers. The male flowers, which are attached to a vine, are the best for stuffing: the females are attached to baby squash, and they are beautiful and delicious cooked together. Peel off the small sharp points around the base of the blossom, and remove the center pistil. Check them for ants and bees, too. For soups, omelettes, and stuffings, I tear the blossoms rather than cut them, as they are so delicate.

The simplest vinaigrette of all is three parts olive oil whisked together with one part vinegar or lemon juice until well emulsified, and seasoned to taste with salt and pepper. Sometimes that’s all you need, especially if the salad is accompanying a complicated or very flavorful dish. Once you’ve mastered the basic vinaigrette, you can become creative and experiment with different oils and vinegars, herbs, garlic, mustards. Just be sure to use really good-tasting stuff. There is no hiding poor-quality oil or highly acidic vinegars, and either one will ruin all your hard work.

Lately I’ve been using a lot of sherry vinegars. These vinegars are made from sherry wine, and there are dozens of different kinds, so you have a lot to explore. Try to find ones that have 8 percent acidity or less. Buy small bottles and taste. My favorites come from Jerez, Spain. These are nutty and rich in flavor, great with poultry and all sorts of greens. I will often add a few drops to a sauce just before serving.

Another staple to keep on hand for making vinaigrettes is Japanese rice vinegar, which is very mild-flavored and has low acidity. Most regular grocery stores stock it: be sure to get the unsweetened kind.

Sausage casings are made from the intestines of pork. My butcher buys them by the hunk. They have been thoroughly cleaned and salted to preserve them. I can buy as many feet as I need. They do keep for a long time if you need to buy the whole hunk. Rinse well in cold running water to desalt before using. We always coat the stuffing nozzle with vegetable oil before sliding the casings on. We keep a skewer handy as we go to pop air bubbles. I find it easiest to work in 3 feet lengths at home. I let the sausage coil onto a baking sheet, then pinch and twist the links after all the sausage meat has been cased.

To caramelize means to cook food so that it is nicely browned on the surface. Whether you are grilling, panfrying, or griddling, the heat level needs to be quite high in order to caramelize food.

The purpose of deglazing is to take advantage of all the tasty goodies stuck to the pan after you have panfried, stir-fried, or sautéed food. Deglazing is usually done with wine or vinegar, but broth or water can also be used. To deglaze, remove the cooked food from the pan and pour off any excess fat or oil; raise the heat, and add the deglazing liquid to the hot pan, scraping to loosen up all the browned bits on the bottom and sides. Stir to dissolve, and boil to reduce the mixture to a thickish glaze.

Deep-frying is best done in an electric deep-fat fryer for automatic heat control, but a heavy-bottomed, deep-sided pan will do if you use a candy or deep-fry thermometer to monitor the heat. It’s very important to get your oil really hot, but never so hot that you exceed the oil’s smoke point, the temperature at which the oil begins to burn and put off smoke and acrid odors. The higher the smoke point, the better the oil’s ability to fry without burning. If oil is heated past its smoke point, it will develop an off odor and bad flavor, which will transfer right over to any food that’s fried in it.

The ideal temperature for deep-frying is 365°F-375°F. Safflower, soybean, sunflower, cottonseed, and corn oils all work well, as they have high smoke points (about 450°F). Peanut oil also has a high smoke point and has the best flavor of all, but peanut allergies are common, so beware. Olive oil is good for shallow panfries below 400°F.

Be sure not to overcrowd the fryer, or the food will not crisp up properly. When frying in batches, make sure you skim out any bits of food or coating that have fallen into the oil, and let the oil return to the cooking temperature between batches. A fryer basket makes life easier when you’re cooking small items.

Erasto, Pablo, and I prefer grilling over wood fires. It’s not the easiest way, but the flavor is the best. We use hardwoods like oak or almond, which are both very easy to get here in California. Stay away from pine or other woods high in pitch. They will send up an acrid smoke that will permeate the food you are grilling, which will ruin its flavor, leave a sooty coating on it, and keep it from crisping and caramelizing properly.

Our next favorite choice is charcoal, but we never use lighter fluid to get it going. We just roll up some newspaper into cones, stack some kindling and a few small logs on top, followed by the charcoal, and light. You should be able to do it with one match. Let the fire burn down to coals; it’s much easier to control your foodstuffs over an even fire than a blazing inferno.

Wear work gloves or cooking mitts unless you have chef’s hands (impervious to heat, but you don’t want them—trust me). Long tongs (never a fork), a spatula or two, a squirt bottle for controlling flare-ups, some clean platters for the cooked foods to be placed on, and you are ready to go.

A Jaccard tenderizing machine is an inexpensive hand-operated tool that does an excellent job of tenderizing meat and poultry. It has tiny steel blades that “pin” the meat as you run the machine across the surface. Available from specialty kitchenware stores or by mail order, this is a great investment, especially if you’re into hunting.

An indispensable device for slicing vegetables thinly and evenly (and quickly) is the mandoline. There are many different kinds for sale, with varying accessories and adjustment capabilities. I favor the Japanese mandolines with carbon steel blades.

A spice grinder is a handy tool for grinding up seeds and spices. Clean it out with a dry brush after every use, to keep the flavors from transferring from one batch to another. An electric coffee grinder also works well.