It may seem strange to open a book on the presocratics with a chapter on Plato (428/7–348/7 bce) and Aristotle (384–322 bce), but there are good reasons for this. I will argue that although they are not often thought about in these terms, their cosmologies and matter theories give the basis for belief in an entirely natural astrology, alchemy and the macrocosm/microcosm analogy. If this is true, why is it important for this study? It establishes the possibility of belief in an entirely natural astrology, alchemy and macrocosm/microcosm relationship. If so, we cannot move from ‘x believed in astrology, alchemy or the macrocosm/microcosm relationship’ to ‘x believed in something non-natural’. It is important to show that this sort of belief was possible in close temporal proximity to the presocratics and may indeed have grown out of presocratic thinking. It opens up the possibility that other disciplines and beliefs which we consider to be magical or non-natural could also be given a natural foundation. It establishes an important link between on the one hand Plato and Aristotle and on the other the Renaissance natural magic tradition who also took astrology, alchemy and the macrocosm/microcosm analogy in an entirely natural manner. It establishes that having the theoretical basis for astrology, alchemy or the macrocosm/microcosm relationship does not entail practice in those areas, either natural or non-natural, a point that will be important in looking at some presocratic thinkers.

I am conscious that, in relation to some ancient philosophers, I am not playing to the most receptive of audiences on these issues and that more sceptical readers may have some worries at this stage. Should those paragons of the rational philosophical tradition, Plato and Aristotle, really be associated with (or tarnished by their association with) astrology, alchemy and the macrocosm/microcosm analogy? So let me be clear and emphatic on some issues. I am not claiming that either Plato or Aristotle should be in any way associated with modern takes on astrology, alchemy or the macrocosm/microcosm analogy. As I made clear in the introductory chapter, there are major differences between ancient and modern views of these issues. I am not even claiming that either Plato or Aristotle was an astrologer or an alchemist. Nor am I claiming that they used the macrocosm/microcosm analogy in the manner of ancient magical practitioners or the manner that became common in the Renaissance natural magic tradition. The claim is merely that one can use the cosmologies and matter theories of Plato and Aristotle to underpin a belief in astrology, alchemy and the macrocosm/microcosm analogy. This is actually a stronger position to defend a fully rational, fully natural view of Plato and Aristotle from. It is not open to the elisions objection, that we have picked the parts of Plato and Aristotle we find rational and have passed over the other parts. A further aim of this chapter is to establish that it was possible to theorise or philosophise about magical disciplines and that magical disciplines could be an integral, rather than a peripheral part of someone’s philosophy. The theoretical basis for some magical disciplines is clearly integral to Plato and Aristotle. It is now commonly acknowledged that the Renaissance natural magic tradition sought the theoretical basis for magical disciplines in Aristotle and Plato.1 We will also look briefly at Bruno and Harvey, two Renaissance thinkers where magical disciplines were integral to their picture of the world.

Astrology

Apart from arguing that the basis for astrology in Plato and Aristotle is natural, I also want to view it in relation to a comment by Dodds in his The Greeks and the Irrational:

Besides astrology, the second century B.C. saw the development of another irrational doctrine which deeply influenced the thought of later antiquity and the whole Middle Age – the theory of occult properties of forces immanent in certain animals, plants and precious stones.2

Clearly, Dodds sees astrology as an irrational doctrine. I’m not going to discuss later Greek astrology to any great extent in this book, but if I did the issues would in some ways be a microcosm of this book’s arguments about the presocratics. I would not want to argue that all belief in astrology after the second century bce was rational. Rather, I would argue that a group of people, including some important people such as Ptolemy, held a belief in astrology which did not entail any non-natural belief or even natural magical belief and was based on an entirely natural cosmology, most often in this case that of Aristotle. Outside these views, there was a spectrum of other views on astrology, ranging from astrology based on natural magic views through to outright non-naturalism and mysticism. So I would reject the old view that astrology:

Fell upon the Hellenistic mind as a new disease falls upon some remote island people.3

There was a wide variety of reactions to the introduction of astrology, some of them based on the entirely natural foundation for astrology one can find in Aristotle.

A final reason for this chapter is to look at Aristotle’s views on the natural. Aristotle held that what happens ‘for the most part’ happens ‘kata phusin’, according to nature, while it is possible for some things to happen ‘para phusin’, contrary to nature. There is no sense in Aristotle though that anything is non-natural, even though it may be para phusin.4 A stone moving upwards is para phusin, but stones may be made to do this under compulsion. One reason why this is important is that Aristotle held a hierarchical view of nature. The celestial realm differed from the terrestrial realm, being constituted from a different sort of matter, aether as opposed to earth, air, fire and water. Aether always executes its natural motion, is always actualising its potentiality such that the heavens for Aristotle are in a sense more actual and so in a sense higher in the order of nature. There is no sense though that anything non-natural happens in the celestial realm for Aristotle. On the contrary, as there is no change in the celestial realm and the motions are entirely natural, everything that happens in the celestial realm happens kata phusin for Aristotle.5 It is also important that for Aristotle there is his god, the prime mover. This god does nothing but actualise its potential, carrying out the highest activity of thinking about thinking. Similar considerations apply as with the celestial realm, only more so. There is no sense that this god does anything non-natural, quite the contrary, what it does is entirely kata phusin for Aristotle. So one could, in the ancient world, have a hierarchical view of nature, and even a belief in a form of deity, without having any belief in the non-natural.

As above with astrology, alchemy and the macrocosm/microcosm relationship, this establishes the possibility of belief in an entirely natural hierarchical conception of nature and an entirely natural god. Again, it is important to show that this sort of belief was possible in close temporal proximity to the presocratics and may indeed have grown out of presocratic thinking. One final point on Aristotle is that he frequently uses biological analogues as paradigms for explanation. One can argue that this includes Aristotle’s physics to some extent. Even if this is so, this does not compromise either his belief in regular behaviour or his belief that everything in one sense is natural.

Aristotle and astrology

There are two groups of passages in Aristotle which are significant in relation to astrology, in On Generation and Corruption book II chapters 10 and 11, and in Meteorology book I chapters 1–3. In On Generation and Corruption Aristotle conducts a thought experiment. He says that:

The problem some see arising here is now solved, that is how each of the bodies (i.e. earth, water, air, fire) travelling to their own places have not, in an unlimited amount of time, become separated from the other bodies. The reason for this is that they change into each other. If each had remained in its own place without change they would have separated long ago. They are though changed due to the double motion and because they are changed none is able to remain in any ordered place.6

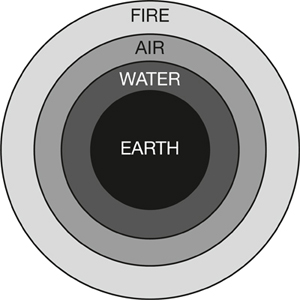

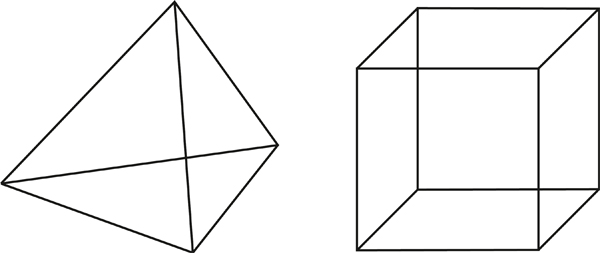

The problem for Aristotle is that the elements, earth, water, air and fire all have natural motions, earth and water towards the centre of the cosmos, air and fire away from it. Left to themselves, they would separate out with earth in the centre and the other elements in concentric shells, like this:

As for Aristotle there is a beginning to the cosmos, there is adequate time for this to have happened already. As it has not, there must be something opposing this tendency. Aristotle’s examples of elements changing into one another are air from water, fire from air and water from fire.7 Why is it that this change occurs and what is the double motion that is referred to here? Aristotle says that:

It is not the primary motion which is the cause of generation and destruction, but motion on the inclined circle.8

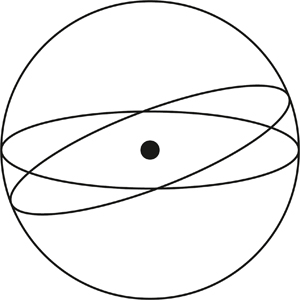

This needs a little explanation in terms of Aristotle’s geocentric cosmology. For Aristotle, the sun has two circular motions around the centre of the cosmos.9 The first of these motions is the primary motion of the cosmos, around the earth in a single day. The second circular motion is inclined to the first and the sun completes this circle in one year. Although we have no precise information on the angle between these two motions, it is generally presumed that this represents the angle of the ecliptic to the earth’s equator.

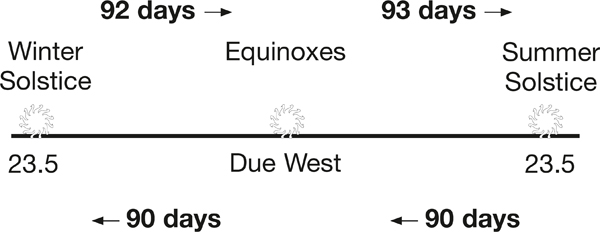

One important effect of the second motion is that it generates a reasonable approximation of where the sun will set on the Western horizon throughout the year. The values for the length of the seasons here are those of Euctemon and Meton.

It was common in the ancient world to refer to the sun as approaching as it moved from winter to summer solstice (days are longer and warmer) and receding as it moved from summer solstice to winter solstice. Aristotle says that:

It [the sun] generates by approaching and being near, it destroys by withdrawing and being far away … Therefore the lifespan of each living thing has a number and is determined. There is an order for all things and all lifespans have a measurable period.10

He also says that:

It would seem that the empirical evidence agrees with our theory, as we see generation with the approach of the sun and destruction with its withdrawal.11

The second Aristotle text is the Meteorology:

The entire terrestrial realm is composed of these bodies [earth, water, air, fire], and as we have said it is the processes which affect them that concern us here. This realm is of necessity contiguous with the upper motions, which means that all of the motions here are steered by the upper motions. As the source of all motion, the upper motions must be accounted as the primary cause. These are eternal, unlimited with respect to place but are always complete. In distinction, all of the other bodies comprise separate regions from each other. The result of this is that fire, earth and their kindred must be accounted as the material reason for coming to be, while the ultimate reason for their motion is the motive ability of the eternally moving things.12

The upper motions here are the motions of the heavens. That the terrestrial motions are ‘steered’ (kubernasthai) is interesting here. kubernein is not a simple verb of motion (which Aristotle could easily have used here) but means to steer, as in to steer a boat, or to guide or govern in a political sense.13 As with the passages from On Generation and Corruption then, the heavens have a significant effect on the terrestrial realm. How is this actually mediated? Aristotle says that:

The circular motion of the primary element and the bodies which are in it, are by their motion always separating, setting on fire and making hot the contiguous bodies in the lower realm.14

How the heavens affect the upper parts of the terrestrial realm in Aristotle has been the subject of much debate, though it is clear that Aristotle believes there is such an effect. Clearly, Aristotle is not an astrologer in that he makes no mention of the zodiac or its houses, no mention of birth/conception dates and does not see human fate or character influenced or determined by the heavens. Aristotle’s concern here is to but to solve a paradox in his theory of motion given the eternity of the cosmos rather than establish a basis for astrology. However, did Aristotle believe that the heavens determine the seasons, the behaviour and lifespan of animals, that all generation and destruction is related to the position of the sun and that the celestial motions ‘steer’ the terrestrial motions.

A few more passages on Aristotle and astrology, firstly from the Metaphysics on the causes of human beings:

The cause of man is (1) the elements in man (viz. fire and earth as matter, and the peculiar form), and further (2) something else outside, i.e. the father, and (3) besides these the sun and its oblique course.15

Aristotle naturally emphasises the role of the sun in relation to the terrestrial realm in his cosmology, but the moon has a role too, as this passage from the Generation of Animals shows:

The moon is a first principle because of her connexion with the sun and her participation in his light, being as it were a second smaller sun, and therefore she contributes to all generation and development. For heat and cold varying within certain limits make things to come into being and after this to perish, and it is the motions of the sun and moon that fix the limit both of the beginning and of the end of these processes.16

Aristotle relates the moon in particular with the behaviour of women:

The period is not accurately defined in women, but tends to return during the waning of the moon. This we should expect, for the bodies of animals are colder when the environment happens to become so, and the time of change from one month to another is cold because of the absence of the moon, whence also it results that this time is stormier than the middle of the month.17

Finally, Aristotle relates the behaviour of the sea-urchin with the moon in the Investigation of Animals:

As a general rule, the testaceans are found to be furnished with their so-called eggs in spring-time and in autumn, with the exception of the edible urchin; for this animal has the so-called eggs in most abundance in these seasons, but at no season is unfurnished with them; and it is furnished with them in especial abundance in warm weather or when a full moon is in the sky.18

While Aristotle did not have a horoscopic astrology himself, Aristotle’s basis for astrology was developed into a full horoscopic astrology by Claudius Ptolemy in his Tetrabiblos. Ptolemy also wrote the Almagest, the definitive ancient work on astronomy. Ptolemy distinguished between astronomy and astrology at the start of the Tetrabiblos, astrology being:

That through which we investigate the configurations themselves and the specific changes they bring about in what they surround.19

Ptolemy also says that:

A certain natural power emanates from the eternal aether and affects the entire region of the earth, subjecting all to change.20

The sun is always in some way changing (arranging) all that is on earth, not only through the changes of the seasons of the year bringing about the generation of animals, the growth of fruit bearing plants, the flowing of waters and the returning of bodies, but also through its daily cycle producing heat, moisture, dryness and cold in a regular manner.21

While Ptolemy develops a horoscopic astrology, it is still Aristotelian in its foundation and involves no non-natural ideas or even sympathies or harmonies. The effects of the heavens on the terrestrial realm are entirely natural for both Aristotle and Ptolemy. That is important to point out, as it is often said that astrology is fundamentally grounded in the ‘ancients’ magical world view’.22

Aristotle and alchemy

It is possible to argue many of the same things about alchemy for Aristotle as about astrology. Aristotle’s theory of matter laid a basis for an entirely natural conception of alchemy that was taken up by many in the alchemical tradition after him. Martin comments that:

It has been well demonstrated that alchemists appropriated Meteorologica IV both in the Middle Ages and in the early modern period.23

Aristotle himself though was not an alchemist either in the modern or ancient senses. Again it is crucial to appreciate how the ancients saw alchemy. It is important to recognise that ancient alchemy was not solely about the transmutation of base metals into gold, as the Leyden papyrus amply demonstrates.24 It was rather more about the transformation of raw materials into something more useful or valuable. So the Leyden papyrus outlines processes for generating gold, but also has processes for generating silver bronze, gems and dyes.

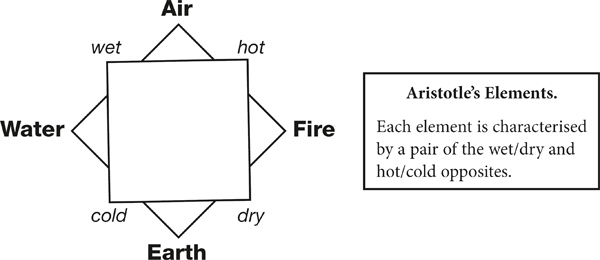

Within Aristotle’s theory of matter, there is nothing which prevents transmutation, and indeed transmutation was a commonplace phenomenon.25 It is also an entirely natural process, in many senses of ‘natural’. Primarily for us, transmutation for Aristotle occurs without any non-natural entities intervening and without any magical processes. Transmutation is also natural in the sense that it occurs in nature without the intervention of human beings. Finally, transmutation is also natural in the Aristotelian sense in that in given circumstances it is what happens for the most part. One can think of this in three ways. Physically, there is nothing which prevents the four Aristotelian elements of earth, water, air and fire from transmuting into each other, as the contraries underlying them (hot, cold, wet dry) alter.

An important example of consistent, natural transmutation of the elements (in all three senses outlined above) for Aristotle is the weather cycle, where water heated by the sun turns into vapour, is cooled and then falls as rain.26 If we want to think of transmutation in terms of the classic alchemical project of the transmutation to gold, gold is constituted out of these elements,27 so the transmutation from non-gold into gold is at least a theoretical possibility.28

If, alternatively, we think in terms of matter and qualities, gold has a certain set of qualities. All qualities are mutable for Aristotle. One might then begin with a plentiful substance that is reasonably similar to gold (e.g. lead), sharing many of the same properties but differing in a few, and seek to change the relevant qualities until one has gold.29 This was a view taken up by many early alchemists. Also significant here for the alchemical tradition was Aristotle’s notion of prime matter, that is matter which has been stripped of all its qualities. For Aristotle this was an abstraction which could not actually exist, but some alchemists sought prime matter, or as close as they could come to it, as a starting point for alchemical transformation. The idea was that with as neutral a starting point as possible, it would then be easier to induce the qualities that they wanted in a substance. Within this project, the reaction of burning Copper with Sulphur to form a black powder was thought significant, as important qualities, such as metalicity and colour appeared to have been removed.

A final way of thinking about transmutation for Aristotle is that he held that geologically, metals were formed in the ground.30 Again, this is an entirely natural process, with no non-natural intervention, no intervention by humans and in the given circumstances happens for the most part. If metals are formed in the ground then there is a process by which they are formed from non-metals. Aristotle held that metals were formed from the moist exhalation of the earth. 31 One might then seek to identify, isolate and replicate this process as part of alchemy.

Aristotle and the macrocosm/microcosm analogy

The macrocosm/microcosm relationship is important for a good deal of natural magic theory. The basic idea is that there is some form of relationship between the cosmos as a whole, the macrocosm, and some smaller part of it, the microcosm, typically but not exclusively a human being. The first occurrence in Greek thought is generally reckoned to be with Democritus, who said that:

Man is a small cosmos (anthrôpôi mikrôi cosmôi).32

We will return to look at this in the chapter on Leucippus and Democritus. This though does not yet give us the full macrocosm/microcosm terminology. Aristotle did not discuss the relationship between macrocosm and microcosm in the abstract at any point. The closest he came to such terminology is in the Physics, when discussing self-motion he says that:

If this can happen to a living thing, what prevents the same thing happening to the universe? If this can happen in the small world (mikrô kosmô) it can happen in the large (megalô).33

In On Generation and Corruption II/10 and 11 we find the comparison of the cycle of the heavenly motions and the weather cycle, the weather cycle being said to ‘imitate’ the heavens.

The cause of this perpetuity of coming-to-be, as we have often said, is circular motion: for that is the only motion which is continuous. That, too, is why all the other things – the things, I mean, which are reciprocally transformed in virtue of their ‘passions’ and their ‘powers of action’ e.g. the ‘simple’ bodies imitate circular motion. For when Water is transformed into Air, Air into Fire, and the Fire back into Water, we say the coming-to-be ‘has completed the circle’, because it reverts again to the beginning. Hence it is by imitating circular motion that rectilinear motion too is continuous.34

This is a passage which was much referred to by the natural magic tradition as a prime example of the macrocosm/microcosm analogy in Aristotle. The notion that the earth’s weather cycle was a microcosm of the macrocosmic motions of the heavens was common in the natural magic tradition, as was the idea that the flow of the blood around the human body was a microcosm, this time with the earth’s weather cycle as the relative macrocosm. Again, we can note that for Aristotle the motions of the heavens and the earth’s weather cycle are both natural in a strong sense. They are both what happens for the most part and so both are kata phusin for Aristotle. It is important to recognise that there were a wide range of macrocosm/microcosm theories with a wide range of supposed relationships between the macrocosm and microcosm. One can, as an elementary explanatory device, say that the electrons of an atom orbit the nucleus as planets orbit the sun and vice versa. One can draw this analogy without suggesting that there is any special relationship between planets and atoms or sun and nucleus. There is no necessity to suggest any causation from planets to electrons, or any harmonic attunement shared by them, or any sympathetic interaction. The natural magic tradition would suppose many types of relationship between the macrocosm and microcosm, such as sympathies and harmonies and of course one can suppose non-natural relations between the two.35 There could also simply be correspondence between macrocosm and microcosm. The macrocosm and microcosm would have similar structures but there would be no causal relationship (no sympathy, no harmony) between them. In this case macrocosm and microcosm would be set up by a benevolent deity during cosmogony. In our case here, Aristotle has the microcosm imitating the macrocosm. I take it as uncontroversial here that Aristotle’s microcosm does not consciously imitate but functions as if it does.

Aristotle on dreams

Aristotle is also the author of what might at first seem a rather strange little work, On Divination by way of Dreams.36 The interpretation of dreams was held to be important in many contexts as they were thought to in some way foretell the future. The provenance of these dreams was commonly thought to be non-natural. Some god had sent the dream, or the person was blessed with foresight. Aristotle seems a little perplexed in the opening passage of On Divination by way of Dreams, as it seems to him there is some basis for divination from dreams but at present no plausible explanation of it:

Concerning divination which occurs in sleep and which is said to arise from dreams, it is not easy either to reject it or to accept it. The fact that everyone, or at any rate most people, suppose there to be something significant about dreams gives the view a certain empirical credibility; nor is it incredible that in some cases there should be divination through dreams, since they have a certain rational structure, and hence one might suppose the same might be true in the case of other dreams as well. On the other hand, the absence of any plausible explanation for the phenomenon tends to discredit it: for in addition to its general implausibility, it is absurd to suppose that a god is the source of such things, and yet that he sends them not to the best and the wisest people, but to anybody at all. Yet if we abandon the divine explanation, none of the others seems reasonable; for it is beyond our understanding to explain how anyone could foresee things occurring at the Pillars of Hercules or on the Borysthenes.37

Aristotle’s attitude is very interesting here. He is loathe to believe that there is a non-natural explanation here even if there seems to be some basis for divination. So at this stage he treats divination by dreams as preternatural – there is some natural explanation but as yet we do not know what. That is useful in confirming that in other situations, with astrology, alchemy and the macrocosm/microcosm analogy, Aristotle is not interested in any non-natural explanation. In On Divination by way of Dreams Aristotle does ask though:

Are then some dreams causes, and others signs, for example of what occurs in the body? At all events, even reputable doctors say that one should pay close attention to dreams.38

Aristotle gives a natural explanation of some veridical dreams. Dreams say of thunder and rain may be caused by our faint hearing of thunder and lightning during our sleep.39 Aristotle also has the following sensible comment to make:

Most [so-called prophetic] dreams are, however, to be classed as mere coincidences, especially all such as are extravagant, and those in the fulfilment of which the dreamers have no initiative, such as in the case of a sea-fight, or of things taking place far away. As regards these it is natural that the fact should stand as it does whenever a person, on mentioning something, finds the very thing mentioned come to pass. Why, indeed, should this not happen also in sleep? The probability is, rather, that many such things should happen.40

The following passage also indicates a rather sceptical attitude on Aristotle’s part:

On the whole, forasmuch as certain of the lower animals also dream, it may be concluded that dreams are not sent by God, nor are they designed for this purpose [to reveal the future]. They have a divine aspect, however, for Nature [their cause] is divinely planned, though not itself divine. A special proof [of their not being sent by God] is this: the power of foreseeing the future and of having vivid dreams is found in persons of inferior type, which implies that God does not send their dreams; but merely that all those whose physical temperament is, as it were, garrulous and excitable, see sights of all descriptions; for, inasmuch as they experience many movements of every kind, they just chance to have visions resembling objective facts, their luck in these matters being merely like that of persons who play at even and odd. For the principle which is expressed in the gambler’s maxim: ‘If you make many throws your luck must change,’ holds in their case also. 41

As Hankinson has pointed out, there are some interesting parallels with the Hippocratic On the Sacred Disease here.42 The Hippocratic author argues that epilepsy (the ‘sacred disease’) cannot be sent by a god, as we would then expect equal incidence of epilepsy through the population.43 In fact some types of people are more prone to it and the divine causation model cannot account for this demographic. At the end of On Divination by way of Dreams Aristotle develops a natural theory of how prophetic dreams which are not mere coincidence might come about:

As for [prophetic] dreams which involve not such beginnings [sc. of future events] as we have here described, but such as are extravagant in times, or places, or magnitudes; or those involving beginnings which are not extravagant in any of these respects, while yet the persons who see the dream hold not in their own hands the beginnings [of the event to which it points]: unless the foresight which such dreams give is the result of pure coincidence, the following would be a better explanation of it than that proposed by Democritus.44

The details of Aristotle’s scheme here need not concern us and we will see Democritus’ theory later on in this book. What is important here, as Huby points out, is that:

Like later theories of the same kind, it does not explain everything, and in particular is no help towards understanding precognition, but for us the important point is that it is intended as a natural, scientific explanation which will replace the traditional supernatural one.45

I include this material on dreams in Aristotle for several reasons. It establishes that in antiquity, directly after the presocratic period it was possible to have an entirely natural explanation of supposedly prophetic dreams. It rounds out our picture of Aristotle as someone who gives entirely natural explanations, whether that concerns the astrological aspects of his cosmology, the alchemical aspects of his matter theory, his use of the macrocosm/microcosm analogy or here, his treatment of prophetic dreams. Finally, as with astrology, alchemy and the macrocosm/microcosm analogy, we will be looking at dreams in relation to the presocratics.

William Harvey and Aristotle

I want to make a very brief excursion into the Renaissance, to show how influential Aristotle’s thinking on macrocosm/microcosm, alchemy and astrology was in the Renaissance natural magic tradition and even with people who we would more straightforwardly associate with an orthodox history of science. William Harvey discovered the circulation of blood, probably in the late 1610s. It is now commonplace for scholars to recognise that Harvey was a dedicated Aristotelian and a great deal of the motivation for his study of the heart and circulatory system came from his reading of Aristotle.46 One issue for Harvey, in breaking from the Galenic view that there were two types of blood in two separate systems in the body, was how the two types of blood could convert into one another within a unitary circulatory system, in the absence of any modern understanding of oxygenated and deoxygenated blood. His answer was to use a macrocosm/microcosm analogy. As the macrocosm, the earth’s weather cycle saw the sun heat water and turn it into vapour, the vapour then cooled and fell as rain, ran through land to the sea, and was heated again. As the microcosm, the heart heated the blood, converting it to nourishing blood, while the blood was cooled in the periphery of the body, converting it back again. Harvey says that:

So the heart is the beginning of life, the Sun of the Microcosm, as proportionably the Sun deserves to be call’d the heart of the world, by whose vertue, and pulsation, the blood is mov’d, perfected, made vegetable, and is defended from corruption and mattering; and this familiar household-god doth his duty to the whole body, by nourishing, cherishing, and vegetating, being the foundation of life, and author of all.47

He also says of the motion of the blood around the body:

Which motion we may call circular, after the same manner that Aristotle sayes that the rain and the air do imitate the motion of the superiour bodies. For the earth being wet, evaporates by the heat of the Sun, and the vapours being rais’d aloft are condens’d and descend in showrs, and wet the ground, and by this means here are generated, likewise, tempests, and the beginnings of meteors, from the circular motion of the Sun, and his approach and removal.48

After Harvey published on the circulation of the blood, for a few years there was debate as to whether this new idea should be accepted. Some of his supporters made considerable use of this macrocosm/microcosm analogy.49 On astrology, Harvey takes up very much the same position as Aristotle, that the heavens guide the terrestrial realm and that the motions of the sun and moon in particular are implicated in the reproduction of animals.50 Harvey translates and quotes a long passage by Aristotle in relation to astrology.51 Harvey’s description of how the two types of blood change into one another draws on standard alchemical terminology for the time, which is heavily influenced by Aristotle’s theory of matter. Some of Harvey’s supporters were quite clear that this was indeed an alchemical change, and Waleus tells us that in relation to Harvey’s circulation theory:

Hence a kind of circulation operates, not unlike that by means of which chemists utterly refine and perfect their spirits.52

In the terminology of the seventeenth century, a ‘chemist’ is an alchemist. There is never any sense in Harvey of anything non-natural occurring, and his use of the macrocosm/microcosm analogy, astrology and alchemical terminology are all entirely natural and are tightly related to his adherence to Aristotelian ideas.

Plato and natural explanation

It is also possible to find an entirely natural basis for astrology, alchemy and the microcosm/macrocosm analogy in Plato. Plato also has some interesting things to say about the natural. In the Timaeus, Plato is keen to give natural explanations for some important phenomena. He tells us that:

The flowing of waters, the fall of thunderbolts53 and the wonderful attraction effects of electricity54 and the magnet,55 all these are not due to any power of attraction, but to the fact that there is no void and that the particles push into each other.56

This is interesting in several respects. Firstly, thunderbolts were held by Homer and Hesiod to be non-natural phenomena, and as we shall see in later chapters, giving them a natural explanation was an important topic for many presocratic thinkers. Here though, Plato explains the thunderbolt in terms of his geometrical atomism, even if the explanation is hardly a full one. These phenomena are not to be explained by any action at a distance, but by the interaction of particles and the fact that particles will always fill a void. 57 That we can explain electricity and magnetism in this manner is also significant. Both might be thought to be difficult to explain by purely natural means in an ancient context and Aristotle tells us that:

Thales supposed the soul to be capable of generating motion, as he said that the magnet has soul because it moves iron.58

We will discuss whether that constitutes a non-natural explanation when we get to Thales but it is interesting to note that Plato gives electricity and magnetism entirely natural explanations. At Timaeus 71aff. Plato attempts to give a natural explanation for the possible use of the liver as a source of divination, something that was common among the Babylonians. Divination and dreams will be an issue when we come to the Hippocratics and we have seen Aristotle’s attempt at natural explanation.

Plato also has some interesting things to say about magic in the Laws. He distinguishes two sorts of poisoning, and having described the normal kind, he says:

Distinct from this is the type which, by means of sorceries and incantations and spells (as they are called), not only convinces those who attempt to cause injury that they really can do so, but convinces also their victims that they certainly are being injured by those who possess the power of bewitchment. In respect of all such matters it is neither easy to perceive what is the real truth, nor, if one does perceive it, is it easy to convince others. And it is futile to approach the souls of men who view one another with dark suspicion if they happen to see images of moulded wax at doorways, or at points where three ways meet, or it may be at the tomb of some ancestor, to bid them make light of all such portents, when we ourselves hold no clear opinion concerning them. Consequently, we shall divide the law about poisoning under two heads, according to the modes in which the attempt is made, and, as a preliminary, we shall entreat, exhort, and advise that no one must attempt to commit such an act, or to frighten the mass of men, like children, with bogeys, and so compel the legislator and the judge to cure men of such fears, inasmuch as, first, the man who attempts poisoning knows not what he is doing either in regard to bodies (unless he be a medical expert) or in respect of sorceries (unless he be a prophet or diviner).59

Plato, like Aristotle, uses the terms kata phusin and para phusin. As with Aristotle, para phusin is often paired with kata phusin and para phusin, while taking the usual sense of ‘contrary to nature’, never has the sense of non-natural. So at Cratylus 393bc there can be unnatural births, at Philebus 32a what is unnatural to the body causes pain, at Republic 444de health is natural and disease unnatural (cf. Timaeus 81eff.) and at Laws 795a ambidextrousness is natural and we only become dominant handed through practice.

That Plato considered material explanations to be inadequate to explain some phenomena does not mean that the explanations he did employ were non-natural. Forms may be of a different order of entities to physical objects, but could hardly be thought of as non-natural, as they have invariant natures of their own and specific ways of relating to physical entities. Often cited in this context is the fact that Plato believed that the heavenly bodies had souls. However, these souls behave in an entirely invariant manner. So Plato says in the Laws:

Those who engaged in these matters accurately would not have been able to use such wonderfully accurate calculations if these entities did not have souls.60

In the Timaeus, there is a hierarchy:

A motion proper to its body, that of the seven motions which is best suited to reason and intelligence. Therefore he made it move in a circle, revolving of itself uniformly and in the same place, and he took from it all trace of the other six motions and kept it free from their wanderings.61

To each of these he gave two motions, one being uniform and in the same place, always thinking the same thoughts concerning the same things, the other being a forward motion obeying the revolution of the same and similar. With regard to the other five motions, they were motionless and still, in order that each might attain the greatest possible perfection.62

Given that these planetary souls obey their own invariant nature, are they non-natural or just another part of nature? The other issue here is that in the Phaedo, Plato has Socrates express his dissatisfaction with the types of explanation given by the natural philosophers.63 Are the new teleological explanations though in any way non-natural? We might similarly look at the different types of explanations offered in the Timaeus and the difference between reason and necessity.

Plato, astrology and macrocosm/microcosm

Plato’s cosmology was used as a basis for astrology in two separate ways. First, Plato’s cosmos was generated by a benevolent god in the best manner possible. One way of thinking about astrology is that the heavenly bodies are not causes of what will happen on earth, but are signs of what will happen. If the cosmos has been put together by a god who cares for human beings, then that god may also have taken forethought about the heavens such that they may be read as signs of what will happen by humans. I do not see any indication of this sort of astrology in Plato, but it is easy to see how this can be built in to derivative cosmologies. The second way in which Plato’s cosmology was used as a basis for astrology was via the macrocosm/microcosm analogy. Plato did not use the macrocosm/microcosm terminology, but in the Timaeus there are important and highly influential accounts of the relation of humans to the cosmos. The key here is that the human mind is put together in the same manner as the world soul. Just as the world soul is constituted out of sameness, being and difference and has two circuits, one of the same and one of the different, so the human mind has two circuits as well. The cosmos, having been brought into being by a well meaning craftsman with only the best in mind,64 is a living, intelligent, ensouled entity. The heavenly bodies, which are alive, intelligent and ensouled and execute (combinations of) regular circular motion, are the visible manifestation of the intelligent life of the cosmos. The Timaeus then tells us that:

God devised and gave to us vision in order that we might observe the rational revolutions of the heavens and use them against the revolutions of thought that are in us, which are like them, though those are clear and ours confused, and by learning thoroughly and partaking in calculations correct according to nature (kata phusin), by imitation of the entirely unwandering revolutions of God we might stabilise the wandering revolutions in ourselves.65

Bound up in this is the standard Platonic moral injunction that we strive to become as much like god as possible. Humans should also imitate the cosmos to maintain good health. The Timaeus tells us that the cosmos has a rocking motion, and as the cosmos keeps itself in motion in order to sustain its own good order, so should humans take a moderate amount of exercise in order to sustain their good order (which equates with their good health).66 Indeed, we can also find a macrocosm/microcosm analogy directly to do with the blood in Plato. Just as the cosmos confines and agitates the particles within it, so does the human body confine and agitate the blood.67

One way of developing an astrology out of this is to suppose that changes in the macrocosm cause changes in the microcosm. One can do that by supposing some form of sympathetic relationship between the position and motion of the heavens and the circuits of the human mind. Did Plato himself believe in astrology? I would answer a firm no to this. There is no system of physical influence from the heavens to the terrestrial realm as we find in Aristotle, nor are there the occasional comments about the influence of the sun or the moon. One can just about get some form of astrology out of one of the mythological passages of the Phaedrus,68 but it is generally accepted that this is part of the mythology and not a part of Plato’s description of the world about us.69 The most interesting passage in the Timaeus is 40c:

The dances of these stars and their juxtapositions with one another, the circling backs and advances of their own cycles, which of these come into contact with each other and which into opposition, which cover each other relative to us, and for what periods they each disappear and again re-appear, sending fears and signs of future events to men who are unable to calculate – to describe all this without visible models would be hard work indeed.70

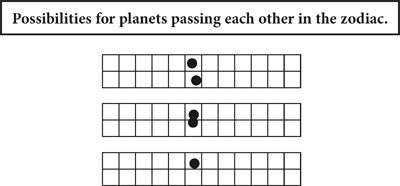

I have argued elsewhere that this is the proper translation for this passage and that Plato displays a good knowledge of assorted celestial phenomena here.71 In particular, he seems to be aware of the phenomena when planets come into conjunction. Planets may pass each other and still be distinct, may appear to touch each other and become one large object or one may cover the other for one small object.

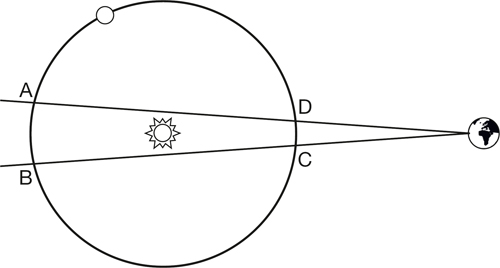

An important phenomenon in Babylonian astrology is that the inferior planets,72 Mercury and Venus, will at times disappear from view as they orbit the sun, being too close to the sun in angular terms to be seen from the earth. They will reappear again on the other side of the sun, and the Babylonians were very good at predicting the times and periods of invisibility. They also saw great astrological significance in whether Mercury or Venus could be seen. This may well be the phenomenon that Plato is referring to in the later part of Timaeus 40cd.

So while Plato himself did not have a belief in astrology, he was aware of phenomena others took to be astrological and it was possible for others coming after Plato to generate a natural astrology out of Plato’s cosmology.

Plato, Giordano Bruno and blood circulation

Let us make a second, briefer visit to the Renaissance. Harvey is famous for establishing that the blood circulated around the body, but others had speculated on this before him. While Harvey’s influences were Aristotelian, others worked in the Renaissance neoplatonism tradition. Giordano Bruno speculated on the circulation but unlike Harvey did not follow this up with skilled dissection and experiment. However, he does say that:

The blood and other humours are in continuous and most rapid circulation.73

So too we are told that the blood from the heart:

Goes out to the whole of the body and comes back from the latter to the heart, as from the centre to the circumference and from the circumference to the centre, proceeding so as to make a sphere.74

Furthermore we are told of:

The blood which in the animal body moves in a circle.75

In De Immenso et Innumerabilibus, Bruno also tells us that:

In our bodies, the blood and other humours in virtue of spirit run around and run back, as with the whole world, with stars and with the earth.76

Bruno quite specifically asks why the blood moves continually in this manner.77 His answer comes by way of a macrocosm/microcosm analogy. What explains the ebb and flow of tides, winds, rain, springs coming from and going into the earth?78 According to Bruno, who rejects several other answers as unsatisfactory,79 it is what Plato called soul and is defined as the number which moves itself in a circle.80 Similarly with the human body, it is the natural circular motion of soul which is the reason for the circulation of the blood. In De Monade, Numero et Figura, Bruno is keen to emphasise the heart as centre of the microcosm, from which the vital spirits go out to the whole of the body.81 There is little doubt that Bruno goes beyond what Plato says. Plato does not specifically mention the circulation of the blood or the speed of its circulation, and it would be hard to extract such ideas from the Timaeus, even though many of the ingredients are there.82 Again though we see how the Renaissance natural magic tradition builds on Aristotle and Plato.

Plato and alchemy

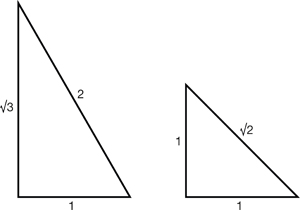

Transmutation of the elements is a straightforward and natural process for Plato. The only oddity is that while water, air and fire can transmute into each other, none of these can transmute into earth and earth cannot transmute into other elements. At the root of Plato’s theory are two basic triangles:

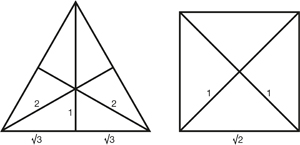

These basic triangles from up into complexes of triangles in the following ways:

These squares then from up into cubes of earth, while the triangles can form up as tetrahedra of fire, octahedra of air or ikosahedra of water.

It is readily apparent that three dimensional figures for fire, water and air can dissociate back into their complex triangles which can then form up again as a different element and that the triangles and squares which go to make up earth are incompatible in this sense with the components of the other three elements. Change between the three elements capable of changing into one another is an entirely natural process for Plato. There were alchemists who took up this theory of matter, though it was far less popular in this respect than the Aristotelian theory.

Conclusion

In Aristotle, we can find an entirely natural basis for ancient astrology, ancient alchemy and the macrocosm/microcosm relationship. As I emphasised at the beginning of this chapter, this is not to say that Aristotle was an astrologer or an alchemist in any sense, merely that a natural basis for these disciplines was possible. So we cannot move from ‘x believed in astrology, alchemy or the macrocosm/microcosm relationship’ to ‘x believed in something non-natural’. Aristotle also has an entirely natural explanation of dreams and prophecies arising from dreams. Aristotle also had an entirely natural conception of god. His god is invariant, has its own nature and does not intervene in the world. It is significant that Aristotle is in close temporal proximity to the presocratics. It is also significant that Aristotle’s views formed the basis of a great deal of natural magic thinking in the Renaissance. A natural belief in disciplines which are often thought magical or non-natural was perfectly possible at the time. In Plato too we can find an entirely natural basis for ancient astrology, ancient alchemy and the macrocosm/microcosm relationship, without Plato being an astrologer or alchemist. That is important for the same reasons it is important in Aristotle. Whether Plato believed everything to be entirely natural is an extremely complex question which I do not intend to go into in depth here, as it depends on definitions of natural/non-natural and interpretations of some highly contested areas of Plato.83 What I want to take away from this chapter is that ancient astrology, ancient alchemy and macrocosm/microcosm relationships could be, and in some cases were, entirely natural. If one likes the terminology, they were rational. When we look at the presocratics we need to bear in mind these possibilities for what we might term ‘magical’ disciplines.